Abstract

In this paper we establish a methodology to predict photoacoustic imaging capabilities from the structure of absorber molecules (sonochromes). The comparative in vitro and in vivo screening of naphthalocyanines and cyanine dyes has shown a substitution pattern dependent shift in photoacoustic excitation wavelength, with distal substitution producing the preferred maximum around 800 nm. Central ion change showed variable production of photoacoustic signals, as well as singlet oxygen photoproduction and fluorescence with the optimum for photoacoustic imaging being nickel(II). Our approach paves the way for the design, evaluation and realization of optimized sonochromes as photoacoustic contrast agents.

Keywords: Naphthalocyanines, Spectroscopy

1. Introduction

Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) has been introduced as a possible translational molecular imaging technique with non-invasive diagnostic and monitoring capabilities, available without the use of ionizing radiation and at low cost [1], [2]. PAI is based on the excitation of absorbers in tissues by a pulsed laser, which initiates local thermal expansion at the site of the absorber and emission of pressure waves detectable by ultrasound, even from deep within tissues; this is a clear advantage over optical imaging methods, which rely on detection of emitted light and are therefore hampered by light scattering and absorption in tissues. PAI can be combined with ultrasound imaging to provide an instantaneous overlay of morphological and molecular imaging and is already available as clinical prototype hand-held devices that could be used at bedside [3]. Measuring photoacoustic signals in a broad range of excitation wavelengths results in photoacoustic spectra that reflect characteristic profiles of individual molecules. Postprocessing of the measured PA data by multispectral unmixing allows for analysis of several molecules at the same time.

Even without injection of contrast agents, PAI can characterize tissues due to specific natural photoacoustic spectra of tissue components. Photoacoustic properties of blood, melanin, lipids and collagen have already been successfully employed for PAI [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Additionally, many exogenous contrast agents/photoacoustic absorbers have been developed, capable of producing PA signals in the near-infrared (NIR) optical imaging window from 700 to 1100 nm where the prevailing endogenous signals from water and the heme group in blood are at their lowest [13], [14]. Some absorbers such as indocyanine green (ICG), IRDye 800CW (IRDye), 2-NGBD, gold nano-spheres and tripods, Alexa750, Na-BD, and others have been coupled to targeting ligands, yielding targeted molecular imaging capabilities [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. However, low photostability, poor excretion characteristics, agent size and non-thermal, excited state relaxation mechanisms render the current PA absorbers suboptimal [24].

Some bio-compatible NIR fluorescent dyes have been discovered to have photoacoustic properties suited for in vivo signal detection. ICG, IRDye and other commercially available cyanine dyes can be used as non-targeted contrast agents but also can be attached to targeting ligands. FDA approval of ICG has granted it widespread use in clinics [25], [26]. However, it has the drawbacks of limited photostability [27], a short half-life in vivo [28] and creating aggregates [29] leading to spectral shifts as a function of concentration and medium [30] and is difficult to conjugate to targeting units [13]. Cyanine dyes, in general, have limited photostability [31] and radiative relaxation (fluorescence) makes up a significant portion of energy release, resulting in less PA signal production.

As an alternative strategy to generate PA signals in organisms, a variety of genetically encoded and expressed NIR PA probes have been characterized in vitro [32] and expressed in vivo [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]. While the one-to-one co-expression of protein with unaltered function is a clear advantage, the clinical infeasibility of genetic marker methods renders them inapplicable to diagnostic development.

Another strategy relies on nanoparticles that have been broadly developed all over the world as multimodal imaging agents and are discussed extensively [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]. Their popularity is owed to their PA signal generation and versatility as contrast agents [44], stability and amenability to bioconjugation, enabling effective biomarker targeting for molecular imaging [45], drug delivery, monitoring [46] and therapy [1], [47], [48]. Their shape and size, as well as modifications, distribution and excretion characteristics vary. Although the raw materials from which they are made may not be toxic, the nanoparticles themselves may be [49]. It is possible that they become lodged in particular organs or organ systems [50] and some, which produce high levels of cytotoxic ROS can have a deleterious effect [51]. Taken together, these complications and disadvantages have created obstacles to the translation of nanomaterials. Further work into mitigation of toxic effects and further characterization of the effects of nanoparticles on in vivo systems is being conducted [52], [53], [54]. Nanoparticles may one day be used routinely in clinics as diagnostics or therapeutic agents but require additional development and do not currently offer the most expedient route to translation.

In summary, although various photoacoustic materials have been successfully used for PAI, the use of PAI in bioimaging is still restricted by the non-ideal properties of these materials with respect to PA efficiency, size, biocompatibility, toxicity and photobleaching. In order to fill this need, biocompatible, small molecule photoacoustic absorbers, termed sonochromes here, characterized by high photostability and optimized for PA signal generation at 800–820 nm, where contributions from oxygenated and deoxygenated blood are equal and minimized within the NIR optical window, should prove most effective, versatile and easily translatable.

Electromagnetic radiation absorbed by a sonochrome is redistributed according to the following energy balance equation:

| (1) |

where Eexc is the excitation energy per Einstein, ΦF is the fluorescence quantum yield, EF is the molar fluorescence energy, ΦT is the triplet state quantum yield, ET is the molar energy of the triplet excited state and α is the fraction of excitation energy released as prompt heat [55]. For long-lived triplet states, ΦT is approximately equal to the singlet oxygen quantum yield Φδ. The α value is proportional to the amplitude of the acoustic wave that is obtained upon excitation with a laser pulse. Thus, higher photoacoustic signals are expected for lower ΦF and ΦT.

We chose the chemically and spectrally stable [56], [57], NIR-absorbing naphthalocyanines (Nc) as macrocycle for the development of an optimized small molecule sonochrome. Ncs have been used for phototherapy [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64]. They are usually packed within oil, micelles, liposomes or particles. Oxygen sensitivity measurements were carried out in vivo using micro- and nano-crystalline powders [65]. These nanoformulations may suffer from similar drawbacks as other nanoparticles. The Cremophor EL solution adapted for this paper renders SiNc a half-life of 20 h [66]. Significant work was conducted to characterize the biodistribution and dark toxicity of axially modified SiNc [67], concluding that there was high biocompatibility. This paper is a stepping stone which sets the design criteria for the creation of water soluble Ncs that would be able to be administered without the aid of nanoformulations.

Recently, other groups showed the first examples of porphyrin, phthalo- and naphthalocyanine formulations used as absorbers in photoacoustic imaging [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75]. A silicon naphthalocyanine (SiNc) has been solubilized in a Cremophor mixture and used for imaging in vivo [71]. However, given its sizable fluorescence and singlet oxygen (1O2) production and its PA response at 760 nm, it is not optimal for PAI [76]. Moreover, production of 1O2 can have deleterious effects on cells and tissues. Additionally, a tin naphthalocyanine (SnNc) modified for improved solubility has been used to image the brain [77]. However, the chosen axial modification does not allow for additional molecular targeting capabilities.

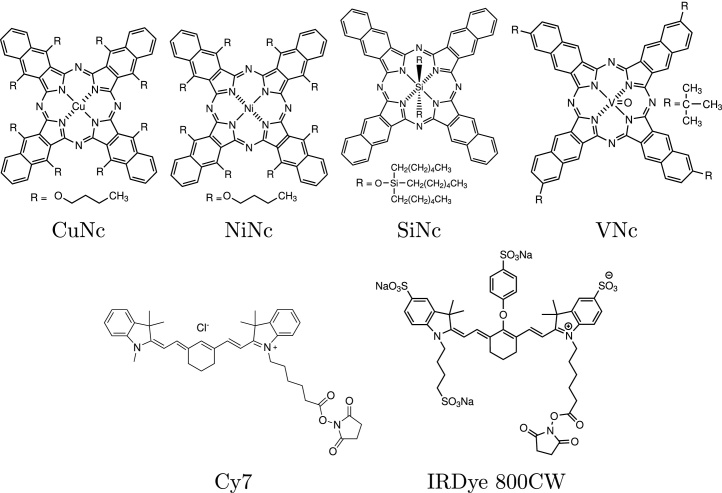

In this work we aim to explore if the production of fluorescence and long-lived species such as triplets and 1O2 can be suppressed through the choice of a metallic center with an open shell configuration (VO2+, d1; Ni2+, d8; Cu2+, d9), to promote fast radiationless deactivation to the ground state. Thus, the absorbed energy would be available exclusively for PA signal generation with α close to unity. We also aim to determine the proper ligand substitution pattern on the macrocycle necessary to shift the maximum absorption (λmax) to 800–850 nm. To this end, we screened four candidate Ncs (Fig. 1) in toluene and Cremophor-EL (Cremophor) in vitro and compared them with two commercially available cyanine dyes. We then were able to show that they could be imaged photoacoustically in an in vivo environment. This paper also seeks to establish a standardized method for the further characterization of photoacoustic dyes using photophysical techniques and correlating them with in vivo photoacoustic spectroscopy. These tools will establish an improved understanding of a defined structure-activity relationship for successful design and realization of novel photoacoustic sonochromes, tailored for in vivo photoacoustic imaging.

Fig. 1.

Photoacoustic dyes used in this study.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy

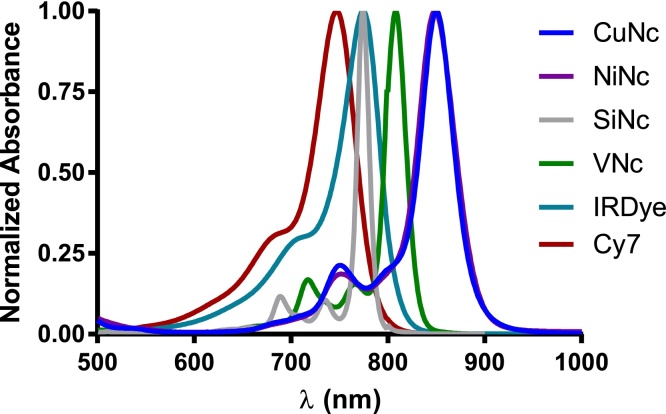

Photophysical properties of all compounds are summarized in Table 1. With the exception of SiNc, all Ncs show a clearly red-shifted Q-band when compared with the water soluble cyanine dyes (Fig. 2). The normalized absorption spectra of the Ncs in toluene show a substitution-dependent maximum ranging from 760 nm (unsubstituted macrocycle, SiNc) through 800 nm (distally tetrasubstituted, VNc) to 850 nm (proximally octasubstituted, CuNc and NiNc). The molar absorption coefficients (ϵ) are comparable for all metallated samples (approximately 2.5 × 105 M−1 cm−1, see Table 1). In the case of silicon, the ϵ is roughly double. The water soluble cyanine dyes have ϵ values in the same range as the Ncs.

Table 1.

Optical and photophysical properties of the contrast agents. Excitation wavelength of maximum photoacoustic intensity (λmax), singlet oxygen quantum yield (ΦΔ), fluorescence quantum yield (ΦF), molar absorption coefficient (ϵ).

| Compound | λmax (nm) | ΦΔ(±0.05) | ΦF(±0.02) | ϵ(±0.5)/M−1 cm−1 | Solvent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuNc | 850 | <0.001 | 0.0003 [78] | 2.1 × 105 | Toluene |

| NiNc | 848 | <0.001 | <0.02 | 2.8 × 105 | Toluene |

| SiNc | 774 | 0.29 | 0.07 [79] | 5.7 × 105 | Toluene |

| VNc | 808 | 0.003 | <0.02 | 2.4 × 105 | Toluene |

| Cy7 | 750a | <0.01 | 0.28 [80] | 2.0 × 105a | Water |

| IRDye 800CW | 774 | < 0.01 | 0.034 [81] | 4.1 × 105 | Water |

Value reported by supplier.

Fig. 2.

Normalized absorption spectra of the dyes investigated in this study at 5 μM.

As observed previously for CuNc, the ΦF was found to be very low [78]. The fluorescence quantum yields of NiNc and VNc are below the detection limit of our integrating sphere, showing that the insertion of an open shell metal center quenches the luminescence. The literature showed that metal free dyes (SiNc, Cy7 and IRDye) exhibit 10–100 times higher fluorescence [79], [80], [81].

2.2. Photoacoustic spectroscopy

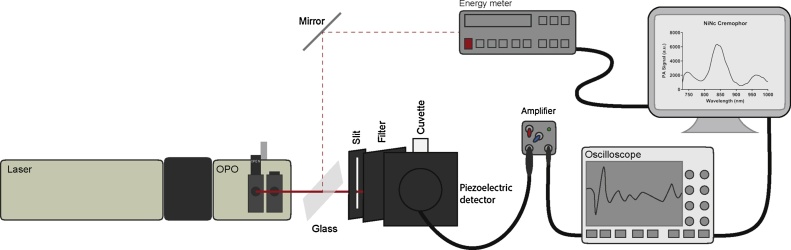

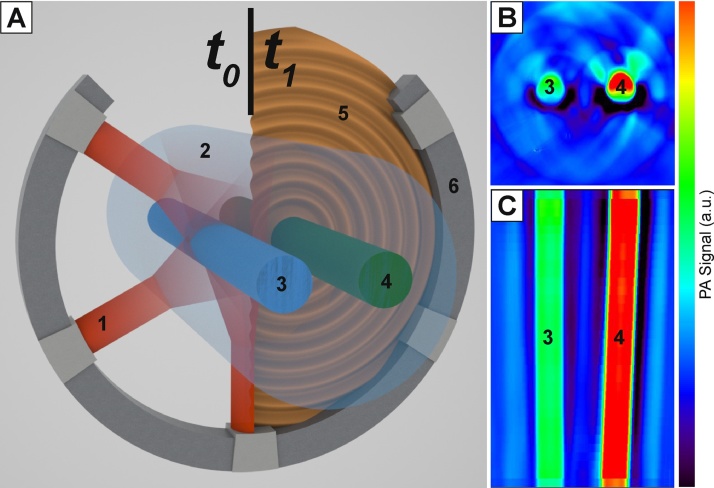

PA signals were measured using two setups. The first, a photoacoustic spectroscopy (PAS) measurement system, as shown in Fig. 3, and the second, a commercially available in vitro and in vivo multispectral optoacoustic tomography (MSOT) imaging system (vide infra) [82].

Fig. 3.

Experimental setup for photoacoustic spectroscopy (PAS).

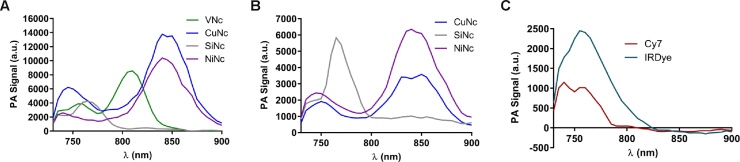

The photoacoustic spectra in toluene are in agreement with the macrocycle substitution dependent shifts shown in the absorption spectra (Fig. 4). For the substituted macrocycles, the vibrational shoulder around 750 nm can be observed. The vibrational shoulder of the unsubstituted macrocycle (SiNc) is outside of the excitation range of the laser in our setup. Interestingly, a band, red shifted in comparison to the Q-band at 770 nm, can be observed for SiNc centered around 830 nm which seems to indicate lateral coupling (J-aggregates). The axial substitution of the central silicon atom prevents stacking (H-aggregates). At constant concentration in toluene, the PA intensity from greatest to least was CuNc, NiNc, VNc, SiNc.

Fig. 4.

Photoacoustic spectra of Ncs (5 μM) in toluene (A) and in Cremophor (B), and of cyanine dyes (5 μM) in water (C). The spectra are corrected for solvent background and laser intensity. Measurements were carried out with the setup described in Fig. 3.

In Cremophor, the same Q-bands with vibrational shoulders can be observed. The ratio between the main band and the vibrational shoulder drops for CuNc, and to a lesser extent for NiNc, which can be attributed to H-aggregation. In addition, the relative intensity of the SiNc J-aggregate band is higher. Both findings demonstrate that intermolecular coupling in aqueous environments affects the photoacoustic performance. As a consequence, CuNc showed a diminished signal intensity, which could be explained by aggregation due to its low solubility, thereby reducing the molar absorption coefficient. NiNc had the highest PA signal followed by SiNc. The band around 970 nm in Cremophor is an artifact created by small variations in the signal created by water absorption.

We can conclude that measurements in toluene are predictive of the wavelengths at which compounds will respond photoacoustically in water and Cremophor. However, we cannot predict the magnitude of the PA output in water or Cremophor using toluene because aggregation phenomena affect the performance.

2.3. Singlet oxygen photoproduction

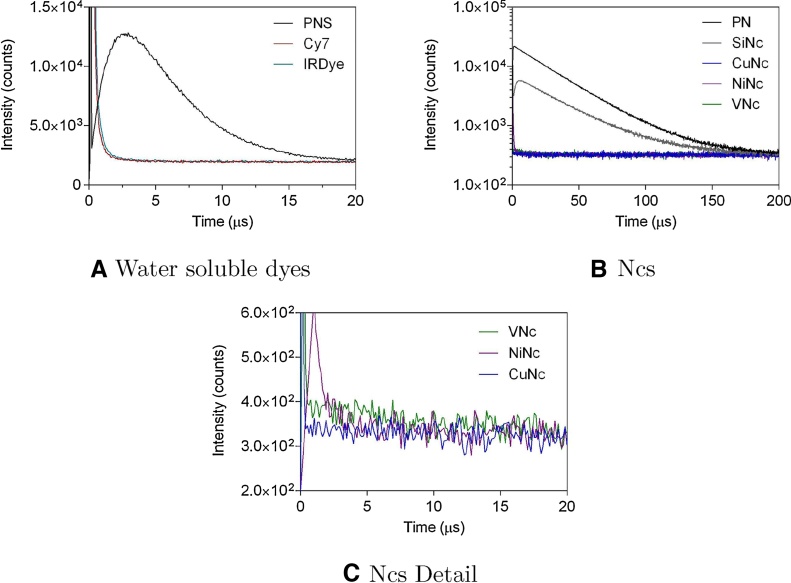

Fig. 5 shows the time-resolved phosphorescence signals at 1275 nm for all Nc and cyanine derivatives. According to our results, SiNc produces 1O2 with a quantum yield of 0.29, which is in good agreement with the literature [76]. All other Ncs produce minute amounts of 1O2, ranging from ΦΔ < 0.001 for CuNc and NiNc (no measurable differences between them) to ΦΔ = 0.003 for VNc. This can be attributed to the fast radiationless deactivation triggered by the open shell metal centers favoring the release of prompt heat and preventing the production of 1O2.

Fig. 5.

Phosphorescence decay curves at 1275 nm for (A) PNS (reference) and water soluble cyanine dyes and (B) PN (reference) and Nc dyes. (C) Shows a detailed depiction of the first 20 μs of b.

In Fig. 5c, one can observe a short spike of NiNc signal at 1 μs. Time-resolved near IR phosphorescence signals are often contaminated by an intense spike at the beginning resulting from a combination of scattered excitation laser light, sample fluorescence and luminescence from optical elements such as filters in the detection path. This is well known and has been extensively documented [83], [84]. The decay of this spurious signal is much faster than the phosphorescence of singlet oxygen.

In the case of cyanine dyes, precise estimation of their ΦΔ is challenging given their strong emission in the NIR window. That fact notwithstanding, comparison of their time resolved phosphorescence signals at 1275 nm with that of 2-sulphonatephenalenone (PNS) [85] suggests that their ΦΔ is below 0.01 (see Table 1).

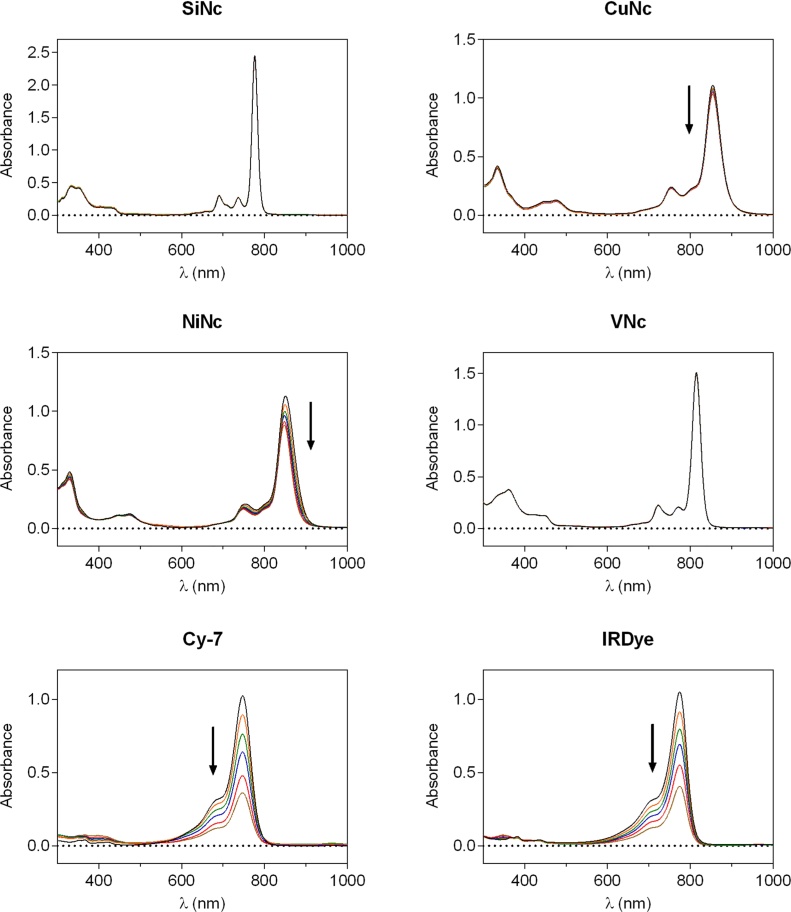

2.4. Photobleaching measurements

The photobleaching behaviors of cyanines and Ncs under NIR irradiation in chlorobenzene are shown in Fig. 6. The Q-band was monitored as a function of NIR irradiation time. We observed significant photobleaching for Cy7 and IRDye. The bleaching of the water soluble dyes can be explained by 1O2 mediated self-oxidation. In contrast, the Ncs showed negligible decomposition with the exception of NiNc displaying a marginal drop in the absorption maximum. The reduced photobleaching observed for Ncs can be explained by the intrinsic stability of the macrocycle and the lack of 1O2 photoproduction in NiNc, CuNc and VNc. Bleaching of the naphthalocyanine compound proposed in this paper is unlikely to be significant in real imaging conditions and indeed has already been used with higher power lasers as a proof of concept for photothermal sensitization [86].

Fig. 6.

Photobleaching of probes exposed to NIR irradiation (λ > 715 nm) by monitoring the absorption spectra as a function of time (t = 0, 10, 20, 30, 45, 60 min).

Interestingly, SiNc, while having a high ΦΔ, did not exhibit significant photobleaching. A proposed mechanism for this result comes from Firey et al. [87], whereby the triplet energy level of SiNc is similar to that of 1O2. Thus, when produced by triplet SiNc, 1O2 can perform reversible energy transfer with the resulting ground state of SiNc itself. The stability of the macrocycle prevents photo-induced decomposition.

2.5. MSOT spectroscopy

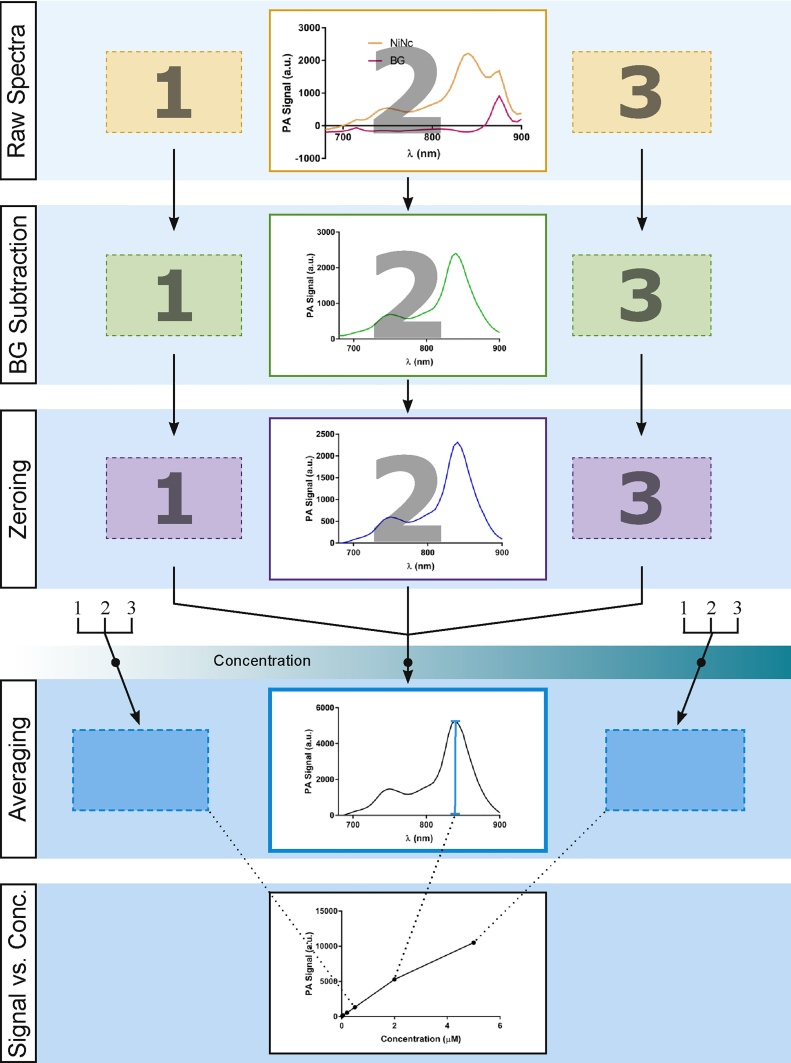

The MSOT, schematically depicted in Fig. 7, was utilized to perform concentration dependence analyses and to assess the utility of the imaging probes in a system designed for the final in vivo application of molecular imaging (Fig. 8). Due to the well controlled tunability of the laser in the MSOT, we were able to measure spectra as a function of concentration. Moreover, we established a systematic method for data analysis.

Fig. 7.

(A) MSOT system depicted schematically. At time t0, NIR laser light (1) is emitted from 5 ports and strikes the agarose phantom (2) where it diffuses and scatters, reaching two straws holding the control medium (3) and the sample (4). At time t1, photoacoustic soundwaves (5) are emitted and detected as they strike the detector ring (6). (B) An axial slice of the cylindrical phantom. The control medium (3), in this case toluene, and the sample (4), in this case 5 μM NiNc, are shown. (C) A longitudinal slice of the same agarose phantom during the same measurement.

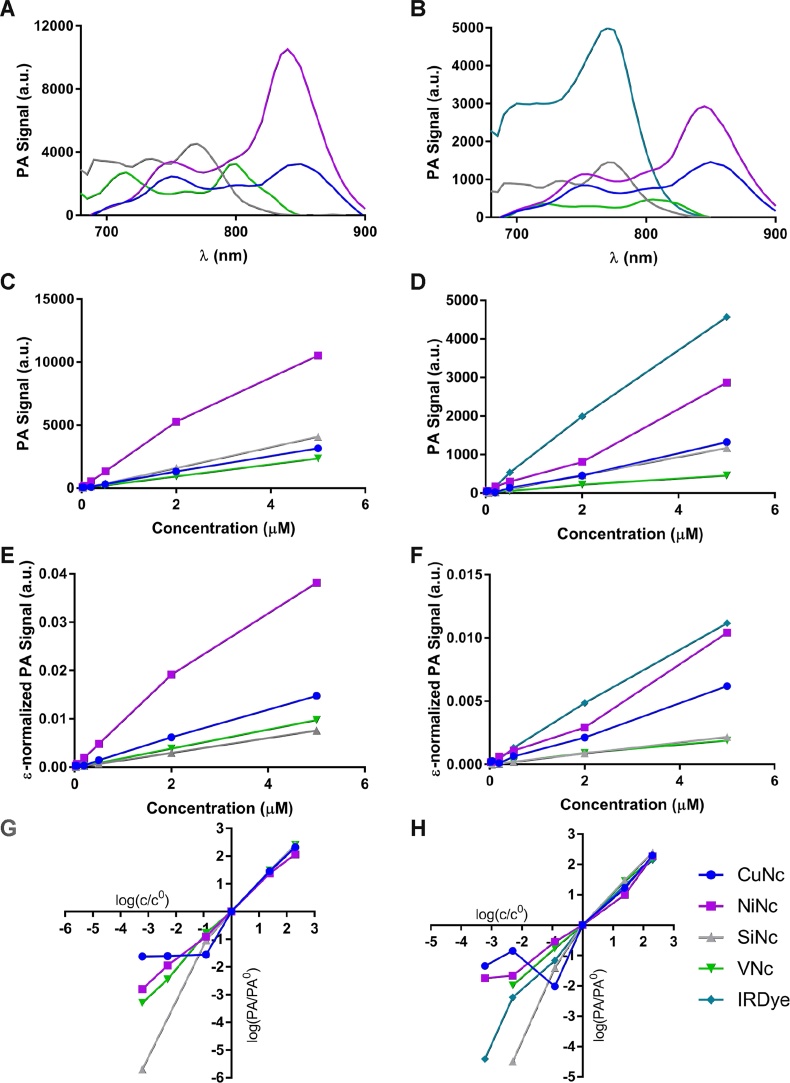

Fig. 8.

Photoacoustic spectra and concentration dependency graphs from reconstructed MSOT photoacoustic images in toluene (A, C, E, G), Ncs in Cremophor and IRDye in water (B, D, F, H). Spectra at a concentration of 5 μM (A, B). C and D are the processed PA signal as a function of concentration. E and F are the photoacoustic intensities divided by molar absorption coefficients (ϵ) of the corresponding dye in toluene. G and H are double logarithmic plots of the normalized photoacoustic signal as a function of normalized concentration where the normalization was the signal and concentration at the lowest verifiable measurement (0.5 μM) respectively. Measurements were carried out on the MSOT system as seen in Fig. 7, which automatically corrects for excitation laser intensity. All calculations were conducted at the excitation maximum of each dye respectively. The signal processing pipeline is depicted in Fig. 10.

Photoacoustic spectra of dye and control samples, in different solvents, imaged within a tissue-mimicking phantom, were acquired (Fig. 8A and B). The MSOT spectroscopy and photoacoustic profiles obtained by performing PAS agree with regard to the wavelengths used to induce the highest photoacoustic response. On the basis of the relative intensities of the Q-band's vibrational shoulders, it is possible to identify a higher degree of aggregation for CuNc, VNc and SiNc as opposed to NiNc.

The MSOT spectroscopy experiments were carried out at different concentrations and the photoacoustic amplitude maxima were plotted, resulting in linear dependencies. This can be rationalized by taking into account that the maximum photoacoustic signal (PAmax, normalized by the excitation intensity) is approximately proportional to the concentration (c), ϵmax, α, and an instrumental constant k:

| (2) |

Thus, the slope is proportional to α · ϵmax and represents the overall photoacoustic performance including the absorption of excitation energy (ϵmax) and conversion into prompt heat (α). For the dyes investigated in this study, SiNc in toluene exhibits the maximum ϵ, followed by NiNc, VNc and CuNc. In aqueous environments, IRDye outperforms the Ncs. In order to evaluate the intrinsic efficiency, i.e. α, we also plotted PAmax/ϵmax as a function of concentration, where the slope corresponds to α · k

| (3) |

From this analysis, we infer that, in toluene, NiNc is significantly more efficient in conversion of excitation energy to prompt heat than CuNc, VNc and SiNc. IRDye and NiNc have comparable slopes in aqueous environments and perform better than CuNc, SiNc and VNc. NiNc, CuNc and VNc are expected to have α values close to unity and comparable slopes (see Fig. 8E and F). The differences could be attributed to the varying degrees of aggregation affecting the photoacoustic spectra measured in phantoms, while the correction was performed using ϵ values obtained by absorption spectroscopy in toluene.

In order to evaluate and visualize the dynamic range, we plotted the logarithm of the photoacoustic maximum normalized by a photoacoustic maximum of verifiable integrity (, at c0 = 0.5 μM) against the logarithm of the concentration ratio c/c0 where a unitary slope is expected (Eq. (4)):

| (4) |

This was verified for all dyes in all media above 0.5 μM. Below this concentration some deviation from linearity is observed. The best fits to a slope of unity were observed in NiNc and VNc.

2.6. Photoacoustic in vivo imaging

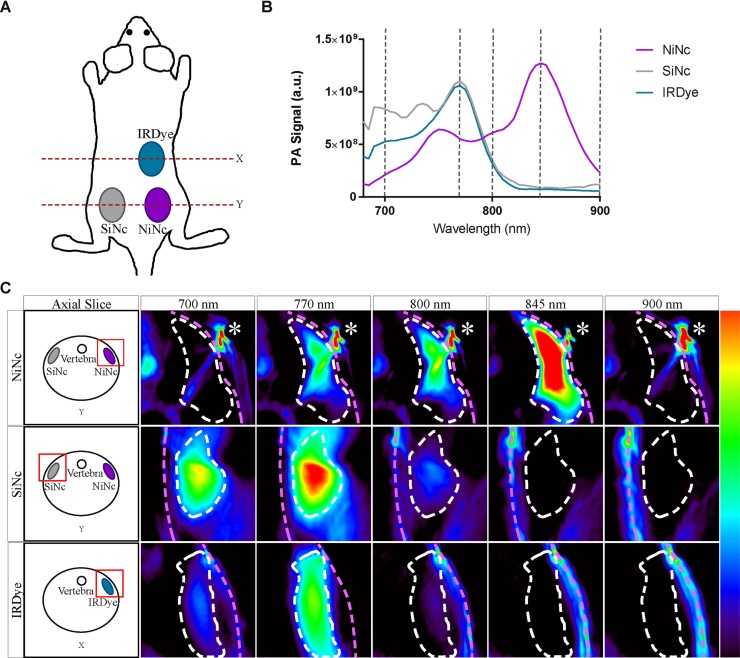

NiNc, SiNc and IRDye were imaged in an in vitro environment made of bio-compatible polyacrylamide (Bio-Gel), which had been injected subcutaneously on the back of living nude mice to form pellets (Fig. 9A). This allowed us to examine the probes in an in vivo context.

Fig. 9.

(A) Overview of a mouse with 3 subcutaneous Bio-Gel pellets, each containing a photoacoustic probe. X and Y indicate 2 axial cuts shown in C. (B) Average spectra (n = 3) retrieved from volumes-of-interest drawn over the pellets. Grey lines indicate wavelengths of the images in C. (C) PA images of pellets from each probe at selected wavelengths. The white dashed line outlines the pellet while the pink dashed line indicates the skin. The asterisk indicates a bubble artifact. Axial slice diagrams are provided for orientation.

By imaging all three probes in a single scan, we were able to control for mouse to mouse variation. The scans were performed in triplicate and the spectra were averaged (Fig. 9B). NiNc provided the highest signal, with SiNc and IRDye showing similar and slightly lower PA signal maximum intensities. Photoacoustic spectra retrieved from the pellets were in agreement with the spectra obtained in the in vitro experiments. Pellet cross-sections are shown in Fig. 9C, exhibiting the photoacoustic response at the wavelengths depicted as grey lines in Fig. 9B. The corresponding axial slice diagrams serve to orient the reader. It should be noted that the persistent high activity in the top right corner of the NiNc slices is likely an air bubble, which can occur when air is trapped by a small hair on the skin. It is an artifact and is not included in the volume of interest which was drawn for this example.

Here we showed retrieval of signal from within a modified in vivo environment. Solubilization of Ncs would facilitate further exploration of their biodistribution and unmixing characteristics in a preclinical setting.

2.7. Concluding remarks

Novel sonochromes with optimized photoacoustic efficiency, low toxicity and small molecular size, which are functionalizable by targeting ligands, are needed for the continued development of preclinical molecular photoacoustic imaging, especially when aiming for future clinical translation. Their development has to overcome current limitations with respect to background signals from natural photoacoustic sources and photobleaching. Finally, evaluating novel probes within an in vivo environment is necessary as their desired application is in molecular imaging in organisms.

PAS and MSOT spectroscopy constitute reliable predictive tools for the design of photoacoustic dyes and their performance in an in vivo environment. We have established a systematic data analysis methodology that enables the comparison of in vitro and in vivo photoacoustic performance.

Based on the substitution pattern, the absorption maximum of the compounds can be shifted (Fig. 4A). Unsubstituted Ncs absorb near 750 nm, distally substituted at 800 nm and proximally substituted at 850 nm. The PA spectra shift similarly to the absorption spectra. Open shell cations favor radiationless relaxation, thus maximizing the photoacoustic performance. With these observations taken together, we propose that Ni2+ as the central metal ion chelating a distally substituted ligand would be optimal for photoacoustic molecular imaging.

To realize tunable, purely photoacoustic sonochromes for in vivo imaging purposes, the naphthalocyanine must be made water soluble. In the future, targetability is also desired and could be achieved through a reactive group being attached to the periphery of the macrocycle. A targeting ligand could then be covalently linked to the molecule, giving it molecular imaging capabilities. Our proposed design, once soluble, will be a tracer, which will improve the preclinical photoacoustic imaging field in terms of ease of unmixing and reproducibility of experiments.

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Compound purveyance

IRDye 800CW (Li-cor, NE, USA), cyanine 7 (Cy7) NHS-Ester (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), copper(II) 5,9,14,18,23,27,32,36-octabutoxy-2,3-naphthalocyanine (CuNc), nickel(II) 5,9,14,18,23,27,32,36-octabutoxy-2,3-naphthalocyanine (NiNc), silicon(IV) 2,3-naphthalocyanine bis(trihexylsilyloxide) (SiNc), vanadyl 2,11,20,29-tetra-tert-butyl-2,3-naphthalocyanine (VNc), phenalanone (PN) (Sigma–Aldrich, MO, USA) were used as purchased. 2-Sulphonatephenalenone (PNS) was self-synthesized [85].

3.2. Solutions

Photophysical properties of the NIR absorbing dyes were measured in either spectroscopic grade toluene [56], [88], [89] (Scharlab, Spain) or in Milli-Q water (Merck Millipore, MA, USA). In order to solubilize the highly nonpolar Ncs in a water-based solution to mimic the in vivo environment, the Cremophor-EL (BASF, Germany) solution used by Bézière and Ntziachristos [71] was employed. The final solution had a solvent composition of 2.5% toluene, 10% Cremophor, 1% 1,2-propanediol (Sigma–Aldrich), 1% N,N-dimethylformamide (Scharlab) and 85.5% PBS (Sigma–Aldrich, pH 7.4). The Nc was dissolved to 200 μM in toluene. The 2-propanediol and N,N-dimethylformamide were added and mixed by sonication for 5 min. Cremophor-EL was added and mixed by pipetting and 30 min of sonication. PBS was added and the mixture was sonicated for a further 30 min. All solutions were prepared at a final dye concentration of 5 μM. These solutions were used for the spectroscopy in this study.

3.3. Absorption spectroscopic techniques

Absorption spectra were recorded using a Varian Cary 6000i dual-beam UV/vis spectrometer. Additionally, molar absorption coefficients (ϵ) were determined according to the Beer–Lambert law in the 0.02–5 μM concentration range.

3.4. Photoacoustic spectroscopy

Photoacoustic spectroscopy (PAS) was conducted using the setup shown in Fig. 3 using the 3rd harmonic of a Surelite II Nd:YAG laser (Continuum, CA, USA). An optical parametric oscillator (OPO) Surelite OPO 12 (Continuum) was used to achieve tuneable wavelengths between 730 and 1000 nm. The resulting beam was passed through a slit to create a rectangular line source. The laser passed through a long pass filter to remove higher frequency photons, left over from lower harmonics of the tripling process.

Samples were measured using a piezoelectric detector 9310 (Quantum Northwest, WA, USA) attached to a fluorescence cuvette in right-angle geometry. The analog signal was amplified using a Panametrics 5662 Preamp (Olympus, Japan) and passed to a Lecroy WaveSurfer 454 oscilloscope (LeCroy, NY, USA) which performed digitalization and signal averaging over 100 shots per measurement. The digital information was transmitted to a PC.

Laser energy was determined by placing a glass slide at a 45° angle in the path of the laser, between the OPO and the slit to split the beam and direct the splitted fraction onto an energy meter RJP-735 (Laser Precision Corporation, CA, USA). This information was also transmitted to the PC.

Spectra were further averaged, solvent background subtracted and normalized by the excitation energy. All measurements were made at 25 °C.

3.5. Singlet oxygen ΦΔ quantum yield determination

The 1O2 near-infrared phosphorescence kinetics were detected by means of a customized Fluotime 200 system (PicoQuant, Germany). Briefly, a diode pumped pulsed Nd:YAG laser (FTSS355-Q, Crystal Laser, Germany) working at a 1 kHz repetition rate at 355 nm was used for excitation of samples.

The luminescence exiting from the sample was filtered using a 1100 nm longpass filter (3RD1100LP, Horiba Scientific, UK) and a 1275 nm bandpass filter (bk-1270-70-B, bk Interferenzoptik, Germany) to isolate the 1O2 emission. A TE-cooled NIR-sensitive photomultiplier tube assembly (H9170-45, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) served as the detector. Photon counting was achieved with a multichannel scaler (NanoHarp 250, PicoQuant GmbH, Germany). The time-resolved emission decays were analyzed by fitting Eq. (5) to 1O2 decays using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA):

| (5) |

The ΦΔ of all compounds were determined by comparing the S0 values of their time-resolved phosphorescence emission at 1275 nm with those of a reference having equal absorption at 355 nm. PNS was used as standard for determination of ΦΔ of Cy7 and IRDye in water. Phenalenone (PN) [90] was used as standard for determination of ΦΔ of all Ncs in toluene.

3.6. Photobleaching

Photobleaching experiments were performed using 5 μM solution of CuNc, NiNc, SiNc and VNc in toluene and Cy7 and IRDye in water. Solutions were irradiated using an A1010 75 W short arc Xe lamp (Photon Technology International, NJ, USA) with a FGL715S 715 nm long pass filter (Thorlabs, NJ, USA) between the excitation light and the cuvette. Samples were illuminated successively for 10, 20, 30, 45 and 60 min cumulatively. Changes in their absorption spectra were monitored using a Varian Cary 6000i dual-beam UV/vis spectrometer.

3.7. MSOT photoacoustic spectroscopy

The Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography system (MSOT) (iThera Medical, Germany) phantoms (objects which stands in for a living subject in imaging studies) consisting of a cylinder of 1.5% agarose with 2% of 20% soy oil as scattering medium and 0.75% 2.5 mM Nigrosin were cast with 2 straws. The straws were removed after hardening and replaced with sealed straws which had been filled with the test solution and a control containing only the solvent. Phantoms were imaged tomographically for the length of the straw taking multispectral photoacoustic images with excitation laser wavelength ranging from 680 to 900 nm at every 5 nm. Images were loaded into an in-house, image processing software, MEDgical (EIMI, Germany). Volumes-of-interest were drawn around areas of the straw not containing air bubbles. Spectra were exported and processed as shown in Fig. 10 to create plots as a function of concentration using GraphPad Prism 7.

Fig. 10.

Schematic representation of the data processing pipeline used in the analysis of MSOT PA spectroscopy data (Fig. 8). Photoacoustic images of the samples were collected in triplicate at different concentrations of the dye, using a phantom setup in the MSOT system as shown in Fig. 7. For each solute–solvent pair at a particular concentration, images of the substance and solvent background were collected simultaneously and the images were analyzed to extract the raw spectra. After solvent background (BG) subtraction the resulting spectra were zeroed (zeroing) using the signal at a wavelength where the substances were known not to absorb. The three resulting spectra were averaged and the photoacoustic signal maximum was extracted. This process was conducted for multiple concentrations and the maxima of the resulting averages were then plotted as a function of concentration.

3.8. Photoacoustic in vivo imaging

Three nude mice (NMRI nu/nu, Janvier, France) were imaged in the MSOT system. Bio-Gel Polyacrylamide Gel (Bio-Gel) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was prepared and mixed with 200 μM Nc-Cremophor mix to a final concentration of 5 μM. IRDye was also mixed with Bio-Gel to a final concentration of 5 μM. 100 μL of each Bio-Gel/dye mixture was injected subcutaneously on the back of each mouse [91]. The mice were placed in the MSOT and imaged tomographically in the region of the plaques with excitation wavelengths from 680 to 900 nm at every 5 nm. Images were analyzed using MEDgical. Volumes-of-interest were drawn around the Bio-Gel pellets and spectra were exported. PA spectra were averaged across 3 mice and were plotted using GraphPad Prism 7.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Beatriz Rodriguez-Amigo, Joaquim Torra and Roger Bresolí-Obach for their guidance, time and effort; Sebastian Wilde, Richard Holtmeier, Claudia Essmann and Renato Margeta for their experimental assistance; Nina Knubel, Krzysztof Sieledczyk and Gabor Duna for help with figure preparation, modeling and shading; and John Pittock for corrections.

This work was supported by a fellowship of the Graduate School of the Cells-in-Motion Cluster of Excellence (EXC 1003 – CiM), University of Münster, Germany to Mitchell Duffy.

Additional financial support for this research was obtained from the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (grant nos. CTQ2013-48767-C3-1-R, CTQ2016-78454-C2-1-R and CTQ2015-71896-REDT). Oriol Planas thanks the European Social Funds and the SUR del DEC de la Generalitat de Catalunya for his predoctoral fellowship (grant no. 2016 FI_B2_00100).

Biographies

Mitchell Duffy is a Ph.D. student in Biology at the University of Münster, Germany at the European Institute for Molecular Imaging (EIMI). He received his Master of Research in Systems and Synthetic Biology from Imperial College London, UK and a B.S. in Biology as well as a B.S. in Computer Science from Tufts University, MA, USA. His current work focuses on the development of photoacoustic probes as well as the photoacoustic and fluorescent imaging of biomarkers in arthritis and cancer.

Oriol Planas received his BSc in Organic Chemistry and MSc in Pharmaceutical Chemistry from IQS School of Engineering (Barcelona). He joined the group of Prof. Dr. Santi Nonell where he pursued his PhD in Chemistry and Chemical Engineering devoted to novel strategies to produce singlet oxygen in biological milieu. His research interests also include the development of strategies for image-guided surgeries using phototheranostic probes.

Andreas Faust received his Ph.D. degree in 2003 (organic chemistry) from the Westfälische Wilhelms-University, Münster, Germany, synthesizing artificial caffeine receptors. From 2004 to 2010, he was a scientific coworker at the department of nuclear medicine and clinical radiology designing and labeling small molecular probes with short lived radionuclides or fluorescent dyes. Since 2011 he is group leader (Chemical Targeting) at the European Institute for Molecular Imaging (EIMI) in Münster, Germany. His main research area is organic and radiopharmaceutical chemistry developing small molecular probes for PET and SPECT as well as optical and optoacoustic imaging techniques.

Thomas Vogl is an independent group leader at the Institute of Immunology, Münster, Germany and the head of laboratory. He studied chemistry in Regensburg and Münster, moved after his PhD thesis to the medical faculty, WWU Münster and focused on alarmin driven sterile inflammatory mechanisms with special focus on S100-biology. In 2006 he got his “venia legendi” (habilitation) in Immunology and was appointed in 2014 as an adjunct Professor at the medical faculty, WWU Münster. Other profound experiences of this co-author are the characterization of phagocyte functions, mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity, biomarker development and more recently in vivo imaging technologies.

Sven Hermann studied medicine at the University of Mainz and graduated in 2001. Subsequently he went for a research fellowship at the University Hospital of Münster and received his doctorate in 2005. After completing his residency in Nuclear Medicine he joined the European Institute of Molecular Imaging (EIMI) in 2009, where he heads a research group in preclinical molecular imaging. His research focuses on imaging of inflammation in the context of atherosclerosis, neuro-inflammation, and infection.

Professor Michael Schäfers received his MD in 1995, followed by a postdoctoral position at the MRC Cyclotron Unit, Imperial College School of Medicine, London. Afterwards, he became an Assistant Professor of Experimental Nuclear Medicine and in 2008 full professor and director of the European Institute for Molecular Imaging (EIMI) and 2013 director of the Department of Nuclear Medicine at the University Hospital in Münster, Germany. His work focusses on multimodal molecular imaging techniques, not only in small animals, but also on the clinical translation of targeted imaging probes. His main research areas are the molecular imaging of cardiovascular inflammation, apoptosis and autonomic innervation, as well as phenotyping of transgenic mouse models and the development of targeted imaging probes.

Santi Nonell is Professor of Physical Chemistry at the Institut Químic de Sarrià (IQS), University Ramon Llull, Barcelona, Spain and Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry. He earned his Ph.D. for work carried out at the Max-Planck-Institut für Strahlenchemie and conducted postdoctoral research at the Arizona State University and the University of California Los Angeles. His core research interests lie in the area of photobiological chemistry, with a focus on singlet oxygen and photomedicine, where he has published more than 170 papers and numerous book chapters. He is the current President of the European Society for Photobiology.

PD Cristian A. Strassert obtained his High School Degree in Chemistry and Biology, graduated in Pharmacy and completed his Licentiate in Chemical Sciences as well as his Doctorate in Organic Chemistry working on metal phthalocyaninates for phototherapy. Afterwards, he finished his Habilitation in Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Münster within the networks of the Center for Nanotechnology and the Cluster of Excellence Cells in Motion. His group has established a broad expertise in synthetic chemistry, molecular photophysics and photobiology towards the realization of phosphorescent materials, hybrid photosensitizers and NIR-absorbers.

Contributor Information

Mitchell J. Duffy, Email: mduffy@uni-muenster.de.

Cristian A. Strassert, Email: ca.s@wwu.de.

References

- 1.Wang L.V., Hu S. Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science (80-). 2012;335:1458–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1216210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zackrisson S., Van De Ven S.M.W.Y., Gambhir S.S. 2014. Light In and Sound Out: Emerging Translational Strategies for Photoacoustic Imaging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taruttis A., Timmermans A.C., Wouters P.C., Kacprowicz M., van Dam G.M., Ntziachristos V. Optoacoustic imaging of human vasculature: feasibility by using a handheld probe. Radiology. 2016;281:256–263. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoelen C.G.A., de Mul F.F.M., Pongers R., Dekker A. Three-dimensional photoacoustic imaging of blood vessels in tissue. Opt. Lett. 1998;23:648. doi: 10.1364/ol.23.000648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X., Pang Y., Ku G., Xie X., Stoica G., Wang L.V. Noninvasive laser-induced photoacoustic tomography for structural and functional in vivo imaging of the brain. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:803–806. doi: 10.1038/nbt839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weight R.M., Viator J.A., Dale P.S., Caldwell C.W., Lisle A.E. Photoacoustic detection of metastatic melanoma cells in the human circulatory system. Opt. Lett. 2006;31:2998. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.002998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H.F., Maslov K., Stoica G., Wang L.V. Functional photoacoustic microscopy for high-resolution and noninvasive in vivo imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:848–851. doi: 10.1038/nbt1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormack D., Al-Shaer M., Goldschmidt B.S., Dale P.S., Henry C., Papageorgio C., Bhattacharyya K., Viator J.A. Photoacoustic detection of melanoma micrometastasis in sentinel lymph nodes. J. Biomech. Eng. 2009;131:074519. doi: 10.1115/1.3169247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein E.W., Maslov K., Wang L.V. Noninvasive, in vivo imaging of blood-oxygenation dynamics within the mouse brain using photoacoustic microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009;14:20502. doi: 10.1117/1.3095799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang B., Su J.L., Amirian J., Litovsky S.H., Smalling R., Emelianov S. Detection of lipid in atherosclerotic vessels using ultrasound-guided spectroscopic intravascular photoacoustic imaging. Opt. Express. 2010;18:4889–4897. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.004889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beard P. Biomedical photoacoustic imaging. Interface Focus. 2011;1:602–631. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2011.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strohm E.M., Moore M.J., Kolios M.C. Single cell photoacoustic microscopy: a review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2016;22:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber J., Beard P.C., Bohndiek S.E. Contrast agents for molecular photoacoustic imaging. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gujrati V., Mishra A., Ntziachristos V., Wang X.L., Liu M.X., Kim C., Prasad P.N., Swihart M.T., Liu Z., Ruers T.J., Ku G., Stafford R.J., Li C., van Dijl J.M., van Dam G.M., Galle P.R., Seitz J.F., Borbath I., Haussinger D., Giannaris T., Shan M., Moscovici M., Voliotis D., Bruix J., Grp S.I.S., Brigman B.E. Molecular imaging probes for multi-spectral optoacoustic tomography. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:4653–4672. doi: 10.1039/c6cc09421j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sano K., Ohashi M., Kanazaki K., Makino A., Ding N., Deguchi J., Kanada Y., Ono M., Saji H. Indocyanine green-labeled polysarcosine for in vivo photoacoustic tumor imaging. Bioconjug. Chem. 2017;28:1024–1030. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatni M.R., Xia J., Sohn R., Maslov K., Guo Z., Zhang Y., Wang K., Xia Y., Anastasio M., Arbeit J., Wang L.V. Tumor glucose metabolism imaged in vivo in small animals with whole-body photoacoustic computed tomography. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012;17:076012. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.7.076012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao J., Xia J., Maslov K.I., Nasiriavanaki M., Tsytsarev V., Demchenko A.V., Wang L.V. Noninvasive photoacoustic computed tomography of mouse brain metabolism in vivo. Neuroimage. 2013;64:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallidi S., Kim S., Karpiouk A., Joshi P.P., Sokolov K., Emelianov S. Visualization of molecular composition and functionality of cancer cells using nanoparticle-augmented ultrasound-guided photoacoustics. Photoacoustics. 2015;3:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng K., Kothapalli S.-R., Liu H., Koh A.L., Jokerst J.V., Jiang H., Yang M., Li J., Levi J., Wu J.C., Gambhir S.S., Cheng Z. Construction and validation of nano gold tripods for molecular imaging of living subjects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:3560–3571. doi: 10.1021/ja412001e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levi J., Kothapalli S.R., Ma T.-J., Hartman K., Khuri-Yakub B.T., Gambhir S.S. Design, synthesis, and imaging of an activatable photoacoustic probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11264–11269. doi: 10.1021/ja104000a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levi J., Kothapalli S.-R., Bohndiek S., Yoon J.-K., Dragulescu-Andrasi A., Nielsen C., Tisma A., Bodapati S., Gowrishankar G., Yan X., Chan C., Starcevic D., Gambhir S.S. Molecular photoacoustic imaging of follicular thyroid carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:1494–1502. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ni Y., Kannadorai R.K., Peng J., Yu S.W.-K., Chang Y.-T., Wu J., Dai H.J., Ntziachristos V., Olivo M., Yelleswarapu C., Rochford J., Zhao H., Cheng Z., Khuri-Yakub B.T., Gambhir S.S. Naphthalene-fused BODIPY near-infrared dye as a stable contrast agent for in vivo photoacoustic imaging. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:11504–11507. doi: 10.1039/c6cc05126j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhen X., Feng X., Xie C., Zheng Y., Pu K. Surface engineering of semiconducting polymer nanoparticles for amplified photoacoustic imaging. Biomaterials. 2017;127:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nie L., Chen X. Structural and functional photoacoustic molecular tomography aided by emerging contrast agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:7132–7170. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00086b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall M.V., Rasmussen J.C., Tan I.-C., Aldrich M.B., Adams K.E., Wang X., Fife C.E., Maus E.A., Smith L.A., Sevick-Muraca E.M. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging in humans with indocyanine green: a review and update. Open Surg. Oncol. J. 2010;2:12–25. doi: 10.2174/1876504101002010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alander J.T., Kaartinen I., Laakso A., Pätilä T., Spillmann T., Tuchin V.V., Venermo M., Välisuo P. A review of indocyanine green fluorescent imaging in surgery. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging. 2012;2012:940585. doi: 10.1155/2012/940585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gathje J., Steuer R.R., Nicholes K.R. Stability studies on indocyanine green dye. J. Appl. Physiol. 1970;29:181–185. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.29.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riefke B., Licha K., Semmler W., Nolte D., Ebert B., Rinneberg H.H. In vivo characterization of cyanine dyes as contrast agents for near-infrared imaging. In: Foth H.-J., Marchesini R., Podbielska H., editors. BiOS Eur.’96, International Society for Optics and Photonics. 1996. pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou J.F., Chin M.P., Schafer S.A. Aggregation and degradation of indocyanine green. In: Anderson R.R., editor. OE/LASE’94, International Society for Optics and Photonics. 1994. pp. 495–505. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landsman M.L., Kwant G., Mook G.A., Zijlstra W.G. Light-absorbing properties, stability, and spectral stabilization of indocyanine green. J. Appl. Physiol. 1976;40:575–583. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.40.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samanta A., Vendrell M., Das R., Chang Y.-T. Development of photostable near-infrared cyanine dyes. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:7406–7408. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02366c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laufer J., Jathoul A., Pule M., Beard P. In vitro characterization of genetically expressed absorbing proteins using photoacoustic spectroscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2013;4:2477–2490. doi: 10.1364/BOE.4.002477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Razansky D., Distel M., Vinegoni C., Ma R., Perrimon N., Köster R.W., Ntziachristos V. Multispectral opto-acoustic tomography of deep-seated fluorescent proteins in vivo. Nat. Photon. 2009;3:412–417. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Filonov G.S., Krumholz A., Xia J., Yao J., Wang L.V., Verkhusha V.V. Deep-tissue photoacoustic tomography of a genetically encoded near-infrared fluorescent probe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:1448–1451. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krumholz A., Shcherbakova D.M., Xia J., Wang L.V., Verkhusha V.V. Multicontrast photoacoustic in vivo imaging using near-infrared fluorescent proteins. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:3939. doi: 10.1038/srep03939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jathoul A.P., Laufer J., Ogunlade O., Treeby B., Cox B., Zhang E., Johnson P., Pizzey A.R., Philip B., Marafioti T., Lythgoe M.F., Pedley R.B., Pule M.A., Beard P. Deep in vivo photoacoustic imaging of mammalian tissues using a tyrosinase-based genetic reporter. Nat. Photon. 2015;9:239–246. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zemp R.J., Paproski R., Forbrich A., Li Y., Campbell R. Opt. Life Sci. OSA; Washington, DC: 2015. In vivo multispectral photoacoustic imaging of gene expression using engineered reporters. p. JW2B.4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L., Zemp R.J., Lungu G., Stoica G., Wang L.V. Photoacoustic imaging of lacZ gene expression in vivo. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007;12:020504. doi: 10.1117/1.2717531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nikoobakht B., El-Sayed M.A. Preparation and growth mechanism of gold nanorods (NRs) using seed-mediated growth method. Chem. Mater. 2003;15:1957–1962. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Homan K., Kim S., Chen Y.-S., Wang B., Mallidi S., Emelianov S. Prospects of molecular photoacoustic imaging at 1064 nm wavelength. Opt. Lett. 2010;35:2663–2665. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.002663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luke G.P., Yeager D., Emelianov S.Y. Biomedical applications of photoacoustic imaging with exogenous contrast agents. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012;40:422–437. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H., Yuan Z., Wu C. Nanoparticle probes for structural and functional photoacoustic molecular tomography. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015:757101. doi: 10.1155/2015/757101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang D., Wu Y., Xia J. Review on photoacoustic imaging of the brain using nanoprobes. Neurophotonics. 2016;3:010901. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.3.1.010901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu L., Cai X., Nelson K., Xing W., Xia J., Zhang R., Stacy A.J., Luderer M., Lanza G.M., Wang L.V., Shen B., Pan D. A green synthesis of carbon nanoparticle from honey for real-time photoacoustic imaging. Nano Res. 2013;6:312–325. doi: 10.1007/s12274-013-0308-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang T., Cui H., Fang C.-Y., Su L.-J., Ren S., Chang H.-C., Yang X., Forrest M.L. Photoacoustic contrast imaging of biological tissues with nanodiamonds fabricated for high near-infrared absorbance. J. Biomed. Opt. 2013;18:026018. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.2.026018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cash K.J., Li C., Xia J., Wang L.V., Clark H.A. Optical drug monitoring: photoacoustic imaging of nanosensors to monitor therapeutic lithium in vivo. ACS Nano. 2015;9:1692–1698. doi: 10.1021/nn5064858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen P.-J., Hu S.-H., Fan C.-T., Li M.-L., Chen Y.-Y., Chen S.-Y., Liu D.-M. A novel multifunctional nano-platform with enhanced anti-cancer and photoacoustic imaging modalities using gold-nanorod-filled silica nanobeads. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:892–894. doi: 10.1039/c2cc37702k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu D., Huang L., Jiang M.S., Jiang H. Contrast agents for photoacoustic and thermoacoustic imaging: a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:23616–23639. doi: 10.3390/ijms151223616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aillon K.L., Xie Y., El-Gendy N., Berkland C.J., Forrest M.L. Effects of nanomaterial physicochemical properties on in vivo toxicity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009;61:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Longmire M., Choyke P.L., Kobayashi H. Clearance properties of nano-sized particles and molecules as imaging agents: considerations and caveats. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2008;3:703–717. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lanone S., Boczkowski J. Biomedical applications and potential health risks of nanomaterials: molecular mechanisms. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006;6:651–663. doi: 10.2174/156652406778195026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jenkins J.T., Halaney D.L., Sokolov K.V., Ma L.L., Shipley H.J., Mahajan S., Louden C.L., Asmis R., Milner T.E., Johnston K.P., Feldman M.D. Excretion and toxicity of gold–iron nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2013;9:356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee J.-A., Kim M.-K., Paek H.-J., Kim Y.-R., Kim M.-K., Lee J.-K., Jeong J., Choi S.-J. Tissue distribution and excretion kinetics of orally administered silica nanoparticles in rats. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014;9(Suppl. 2):251–260. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S57939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naz F., Koul V., Srivastava A., Gupta Y.K., Dinda A.K. Biokinetics of ultrafine gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) relating to redistribution and urinary excretion: a long-term in vivo study. J. Drug Target. 2016;24:720–729. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2016.1144758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braslavsky S.E., Heibel G.E. Time-resolved photothermal and photoacoustic methods applied to photoinduced processes in solution. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:1381–1410. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sapunov V.V. 2, 3-Naphthalocyanine dimers in liquid solutions. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 1990;53:1213–1216. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang T., Cui H., Fang C.-Y., Cheng K., Yang X., Chang H.-C., Forrest M.L. Targeted nanodiamonds as phenotype-specific photoacoustic contrast agents for breast cancer. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2015;10:573–587. doi: 10.2217/nnm.14.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cuomo V., Jori G., Rihter B., Kenney M.E., Rodgers M.A. Liposome-delivered Si(IV)-naphthalocyanine as a photodynamic sensitiser for experimental tumours: pharmacokinetic and phototherapeutic studies. Br. J. Cancer. 1990;62:966–970. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wöhrle D., Shopova M., Müller S., Milev A.D., Mantareva V.N., Krastev K.K. Liposome-delivered Zn(II)-2,3-naphthalocyanines as potential sensitizers for PDT: synthesis, photochemical, pharmacokinetic and phototherapeutic studies. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 1993;21:155–165. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(93)80178-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hill R., Garrett J., Reddi S., Esterowitz T., Liaw L.-H., Ryan J., Shirk J., Kenney M., Shimuzu S., Berns M. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) of the ciliary body with silicon naphthalocyanine (SINc) in rabbits. Lasers Surg. Med. 1996;18:86–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9101(1996)18:1<86::AID-LSM11>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Müller S., Mantareva V., Stoichkova N., Kliesch H., Sobbi A., Wöhrle D., Shopova M. Tetraamido-substituted 2,3-naphthalocyanine zinc(II) complexes as phototherapeutic agents: synthesis, comparative photochemical and photobiological studies. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 1996;35:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(96)07294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mantareva V., Shopova M., Spassova G., Wöhrle D., Muller S., Jori G., Ricchelli F. Si(IV)-methoxyethylene-glycol-naphthalocyanine: synthesis and pharmacokinetic and photosensitizing properties in different tumour models. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 1997;40:258–262. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(97)00066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Josefsen L.B., Boyle R.W. Photodynamic therapy and the development of metal-based photosensitisers. Met. Based Drugs. 2008;2008:276109. doi: 10.1155/2008/276109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taratula O., Doddapaneni B.S., Schumann C., Li X., Bracha S., Milovancev M., Alani A.W.G., Taratula O. Naphthalocyanine-based biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles for image-guided combinatorial phototherapy. Chem. Mater. 2015;27:6155–6165. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ilangovan G., Manivannan A., Li H., Yanagi H., Zweier J.L., Kuppusamy P. A naphthalocyanine-based EPR probe for localized measurements of tissue oxygenation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;32:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zuk M.M., Rihter B.D., Kenney M.E., Rodgers M.A.J., Kreimer-Birnbaum M. Effect of delivery system on the pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of bis(di-lsobutyl octadecylsiloxy)silicon 2,3-naphthalocyanine (isoBOSINC), a photosensitizer for tumor therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 1996;63:132–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb03004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brasseur N., Nguyen T.L., Langlois R., Ouellet R., Marengo S., Houde D., van Lier J.E. Synthesis and photodynamic activities of silicon 2,3-naphthalocyanine derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:415–420. doi: 10.1021/jm00029a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luciano M., Erfanzadeh M., Zhou F., Zhu H., Bornhütter T., Röder B., Zhu Q., Brückner C. In vivo photoacoustic tumor tomography using a quinoline-annulated porphyrin as NIR molecular contrast agent. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:972–983. doi: 10.1039/c6ob02640k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Y., Jeon M., Rich L.J., Hong H., Geng J., Zhang Y., Shi S., Barnhart T.E., Alexandridis P., Huizinga J.D., Seshadri M., Cai W., Kim C., Lovell J.F. Non-invasive multimodal functional imaging of the intestine with frozen micellar naphthalocyanines. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014;9:631–638. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou Y., Wang D., Zhang Y., Chitgupi U., Geng J., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Cook T.R., Xia J., Lovell J.F. A phosphorus phthalocyanine formulation with intense absorbance at 1000 nm for deep optical imaging. Theranostics. 2016;6:688–697. doi: 10.7150/thno.14555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bézière N., Ntziachristos V. Optoacoustic imaging of naphthalocyanine: potential for contrast enhancement and therapy monitoring. J. Nucl. Med. 2015;56:323–328. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.147157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Y., Lovell J.F. Porphyrins as theranostic agents from prehistoric to modern times. Theranostics. 2012;2:905–915. doi: 10.7150/thno.4908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Y., Lovell J.F. Recent applications of phthalocyanines and naphthalocyanines for imaging and therapy. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2017;9:e1420. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lu H.D., Lim T.L., Javitt S., Heinmiller A., Prud’homme R.K. Assembly of macrocycle dye derivatives into particles for fluorescence and photoacoustic applications. ACS Comb. Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.7b00031. acscombsci.7b00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wei J.-P., Chen X.-L., Wang X.-Y., Li J.-C., Shi S.-G., Liu G., Zheng N.-F. 2017. Polyethylene Glycol Phospholipids Encapsulated Silicon 2,3-Naphthalocyanine Dihydroxide Nanoparticles (SiNcOH-DSPE-PEG(NH2) NPs) for Single NIR Laser Induced Cancer Combination Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Firey P.A., Rodgers M.A.J. Photo-properties of a silicon naphthalocyanine: a potential photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 1987;45:535–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb05414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang H., Wang D., Zhang Y., Zhou Y., Geng J., Chitgupi U., Cook T.R., Xia J., Lovell J.F. Axial PEGylation of tin octabutoxy naphthalocyanine extends blood circulation for photoacoustic vascular imaging. Bioconjug. Chem. 2016;27:1574–1578. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Soldatova A.V., Kim J., Rosa A., Ricciardi G., Kenney M.E., Rodgers M.A.J. Photophysical behavior of open-shell first-row transition-metal octabutoxynaphthalocyanines: CoNc(OBu)8 and CuNc(OBu)8 as case studies. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:4275–4289. doi: 10.1021/ic7023204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jin Y., Ye F., Zeigler M., Wu C., Chiu D.T. Near-infrared fluorescent dye-doped semiconducting polymer dots. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1468–1475. doi: 10.1021/nn103304m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dempsey G.T., Vaughan J.C., Chen K.H., Bates M., Zhuang X. Evaluation of fluorophores for optimal performance in localization-based super-resolution imaging. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:1027–1036. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Azhdarinia A., Wilganowski N., Robinson H., Ghosh P., Kwon S., Lazard Z.W., Davis A.R., Olmsted-Davis E., Sevick-Muraca E.M. Characterization of chemical, radiochemical and optical properties of a dual-labeled MMP-9 targeting peptide. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:3769–3776. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ntziachristos V. Going deeper than microscopy: the optical imaging frontier in biology. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scurlock R.D., Lu K.-K., Ogilby P.R. Luminescence from optical elements commonly used in near-IR spectroscopic studies: the photosensitized formation of singlet molecular oxygen (1Δg) in solution. J. Photochem. 1987;37:247–255. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jiménez-Banzo A., Ragàs X., Kapusta P., Nonell S. Time-resolved methods in biophysics. 7. Photon counting vs. analog time-resolved singlet oxygen phosphorescence detection. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008;7:1003. doi: 10.1039/b804333g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nonell S., González M., Trull F.R. 1H-phenalen-1-one-2-sulfonic acid an extremely efficient singlet molecular oxygen sensitizer for aqueous media. Afinidad. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Busetti A., Soncin M., Reddi E., Rodgers M.A.J., Kenney M.E., Jori G. Photothermal sensitization of amelanotic melanoma cells by Ni(II)-octabutoxy-naphthalocyanine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1999;53:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(99)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Firey P.A., Ford W.E., Sounik J.R., Kenney M.E., Rodgers M.A.J. Silicon naphthalocyanine triplet state and oxygen. A reversible energy-transfer reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:7626–7630. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Becker R.J., Goedert R.V., Clements A.F., Whittaker T.A. Imaging of silicon naphthalocyanine in toluene. MRS Proc. 1997;479:111. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang S.S., Wei T.-H., Huang T.-H., Chang Y.-C. Z-scan study of thermal nonlinearities in silicon naphthalocyanine-toluene solution with the excitations of the picosecond pulse train and nanosecond pulse. Opt. Express. 2007;15:1718–1731. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.001718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oliveros E., Suardi-Murasecco P., Aminian-Saghafi T., Braun A.M., Hansen H.-J. 1H-phenalen-1-one: photophysical properties and singlet-oxygen production. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1991;74:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang X., Goncalves R., Mosser D.M. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1401s83. Chapter 14. Unit 14.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]