Abstract

Background:

India faces a significant gap between the prevalence of mental illness among the population and the availability and effectiveness of mental health care in providing adequate treatment. This discrepancy results in structural stigma toward mental illness which in turn is one of the main reasons for a persistence of the treatment gap, whereas societal factors such as religion, education, and family structures play critical roles. This survey-based study investigates perceived stigma toward mental illness in five metropolitan cities in India and explores the roles of relevant sociodemographic factors.

Materials and Methods:

Samples were collected in five metropolitan cities in India including Chennai (n = 166), Kolkata (n = 158), Hyderabad (n = 139), Lucknow (n = 183), and Mumbai (n = 278). Stratified quota sampling was used to match the general population concerning age, gender, and religion. Further, sociodemographic variables such as educational attainment and strength of religious beliefs were included in the statistical analysis.

Results:

Participants displayed overall high levels of perceived stigma. Multiple linear regression analysis found a significant effect of gender (P < 0.01), with female participants showing higher levels of perceived stigma compared to male counterparts.

Conclusion:

Gender differences in cultural and societal roles and expectations could account for higher levels of perceived stigma among female participants. A higher level of perceived stigma among female participants is attributed to cultural norms and female roles within a family or broader social system. This study underlines that while India as a country in transition, societal and gender rules still impact perceived stigma and discrimination of people with mental illness.

Keywords: India, mental health, perceived discrimination, perceived stigmatization, South Asia, urban

INTRODUCTION

Stigma and perceived stigma of mental illnesses

An extensive body of literature discusses a relationship between sociocultural norm, gender, and roles with stigma and discrimination toward people with mental illness.[1,2,3,4,5,6] Current definitions emphasize that stigma is related to a display of disgrace and shame, which usually elicits negative attitudes toward its bearers.[1,5,7,8,9] Attaching stigma to mental illness originates among other factors from a lack of mental health literacy and insufficient public display of positive treatment outcomes, which both reinforce stigmatization and perceived discrimination by the public.[7] At its core, the concept of stigma essentially incorporates three main elements, namely prejudicial attitudes, insufficient knowledge, and discriminatory behavior.[7,9] The attached stigma on individuals affected by mental disorders often makes them prone to severe consequences such as significant loss of self-esteem, self-stigmatization, reduced job opportunities, and social exclusion.[1,2,10,11,12] Social withdrawal either due to a loss of self-esteem or self-stigmatization often constitutes a substantial obstacle to the early detection and adequate treatment of mental illness, thus reinforcing a vicious circle of stress and reduced social functioning for the individual.[8] In that context, self-stigma and a closely related perceived stigma of persons with mental health problems are conceptualized as an internalization of sociocultural dimensions of discriminatory experiences by the mentally ill that negatively affect self-perception and active coping behavior.[26] Another essential factor of perceived stigma is the experience of anticipated discrimination, the expression of expected societal rejection, from which individuals with mental illness suffer, further leading to loss of self-esteem, social withdrawal, demoralization, a decrease in help-seeking behavior, and lower quality of life[1,9,13] as well as secrecy about mental illness.[14,15]

Mental illness in India

Modern India is a country characterized by a rapid growth in population as well as the transition from a low-income country to a middle-income country regarding its sociodemographic and epidemiological dimensions.[16] However, in India, a nation with more than 1.3 billion citizens, statistics regarding the exact prevalence of individuals with mental illness remain insufficient. Recent prevalence estimates range from 5.8% to 7.3% of the total population,[17] or in numbers to around 150 million people in India affected by mental illness.[16] These prevalence rates and low numbers of approximately 0.3 psychiatrists per 100,000 inhabitants compared to the global figure of 1.2/100,000[17] reveal an enormous challenge for the mental health-care system in India. Moreover, the availability of psychologists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses remains equally low and is too often restricted to urban areas.[17] One of the central barriers to adequate treatment of mental illness in India is a lack of funding[14,18,19] leading to ineffective help-seeking behavior and often poorer treatment outcomes, both associated with stigma toward mentally ill patients and their caregivers.[14,20] Governmental health and social priorities coined by the transition[16] result in low-spending priorities toward mental health care which intensifies societal and structural stigma toward mental illness. A study in 2010[18] mapped the mental health spending in several low-middle income countries and found that in the Indian state of Kerala only 2% of the national health budget was allocated to mental health care. To some degree, similar patterns of national financial priorities can be observed in other low-[48,49] and middle-income countries, and even in high-income countries such as Germany.[21,22] However, stigma toward individuals who have mental illness in Asian countries is often disproportionally higher than that in Western countries.[20,48] In South and Southeast Asian nations, especially in India, prejudice of mentally ill people being dangerous and aggressive[20,23] adjunct with factors such as religion and lower education[24] result in a higher public desire for social distance to affected individuals. In addition to that, the substantial lack of adequate health-care providers coupled with a personal burden and the lack of awareness within the population ultimately leads to a deficient quality of mental health care.[16,48]

Aim of the study

The primary purpose of the current study is to analyze the perception of mental illness in India. By investigating how specific sociodemographic factors affect the perception of mental illness within the Indian population and how they are related to perceived discrimination and stigmatization, the study draws a conclusion regarding the provision of mental health care in a rapidly transitioning and culturally diverse country. Since India is a vast country containing different cultural, societal, religious, and linguistic populations and norms,[25] this study focuses on five major metropolitan cities, namely Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, Kolkata, and Lucknow, representing different major urban regions of the country.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A protocol-based data collection process was carried out with the assistance of a market research firm, Panoramix™, after personal training of the interviewer with the researcher and second author AZ in India. The assistance of the market research company with a large and reliable database of possible respondents ensured an accurate and consistent completion of the questionnaires resulting in a very high completion rate and informed consent of all participants. Although the interviews consisted of individuals who voluntarily registered within the market and social research firm, resulting in a convenience sample, we used prior quota sampling in all cities for gender, age, and religion according to the census of India. In detail, inclusion criteria were determined as participants who were willing and agreed to be contacted by the research firm and further filled out the informed consent. Exclusion criteria were defined by people who did not want to be contacted or did not match the predefined parameters, according to the database of the research partner. Further, the data collection did not involve a probability-based selection method. Participants were balanced recruited from five major cities representing different regions in India, urban areas where Panoramix™ commonly conduct public surveys with registered individuals. These metropolitan areas include Mumbai (n = 297), Chennai (n = 151), Lucknow (n = 184), Kolkata (n = 149), and Hyderabad (n = 139). Recruited participants’ age ranged between 18 and 65 years.

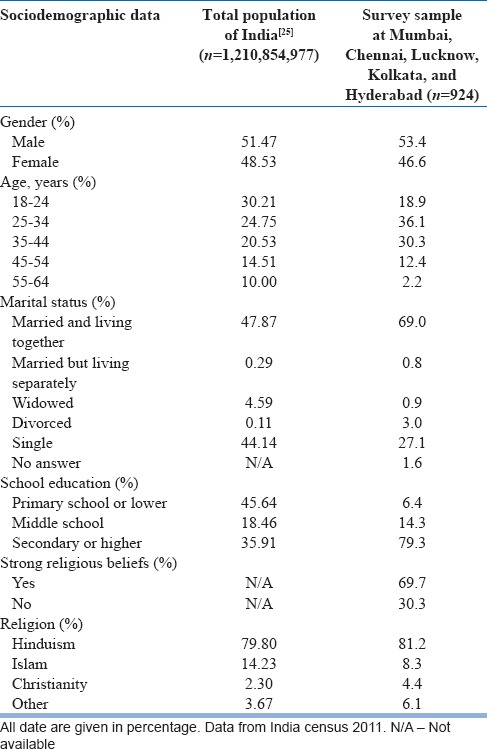

Table 1 presents the detailed demographic characteristics of the sample in comparison with the Indian census of 2011.[25]

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of survey sample in percentage in comparison to the total population of India according to the census of 2011

Questionnaire

The interview included questions to assess respondents’ perceived stigma toward people with mental illness in social situations using Link's Perceived Discrimination and Devaluation Scale (PDDS).[26] Since the questionnaire was first conceived in the context of Western societies, the wording was adapted in some cases for better understanding in the cultural and linguistic context of the local populations.[27] These cases included religious, spiritual, and educational settings. The questionnaire took 10–15 min to complete. Furthermore, relevant sociodemographic information was gathered to assess influential factors such as gender, age, religion, the strength of religious devotion, and educational attainment.

There was no potential conflict of interest regarding any of the authors in relation to the market research firm. The study design using the Link's PDDS among other measures has been applied in high-, middle-, and low-income countries including Germany and Vietnam for use in the healthy population nonpatient groups and has been approved for Berlin, by the ethics committee of the Department of Psychology, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany, the Military Academy of Medicine Hanoi, Vietnam,[48,49] and recently by the Asian Institute of Public Health, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, for assessing public attitudes in rural settings in India. Respondents did not receive any financial compensation.

Translation procedure

The original questionnaires were translated from English into the respective local languages using a back-translation method.[28] Furthermore, upon informed consent of the participants, structured interviews were administrated by psychologists who have undergone a specific training beforehand which is a standard methodology when recruiting greater sample sizes.

Perceived stigma

Perceived stigma was assessed through the use of the PDDS[26] for which respondents had to indicate their view regarding most Indian's attitudes toward former psychiatric patients. The degree of agreement with a statement was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “definitely true” (1) to “definitely not true” (5). Lower scores correspond to lower levels of perceived stigma, while higher scores correspond to higher levels of perceived stigma. The scale consisted of 12 items covering participants’ attitudes toward a variety of topics such as intelligence, relationships, and work issues of persons with mental illness.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM program SPSS Statistics for Mac OS X Version 21.0 (IBM, USA). The first step involved reversing six of the twelve items. A mean score was calculated for all the 12 items of the scale. Next, a sum score (SS) was calculated for participants’ responses and the total was divided by 12 resulting in a range from 1 to 5 representing perceived stigma for each participant. A multiple linear regression was conducted using the mean score as the dependent variable and sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, marital status, education attainment, the strength of religious beliefs, and religion as independent variables. Cronbach's alpha (α = 0.48) was calculated to determine the reliability of the questionnaire used.

RESULTS

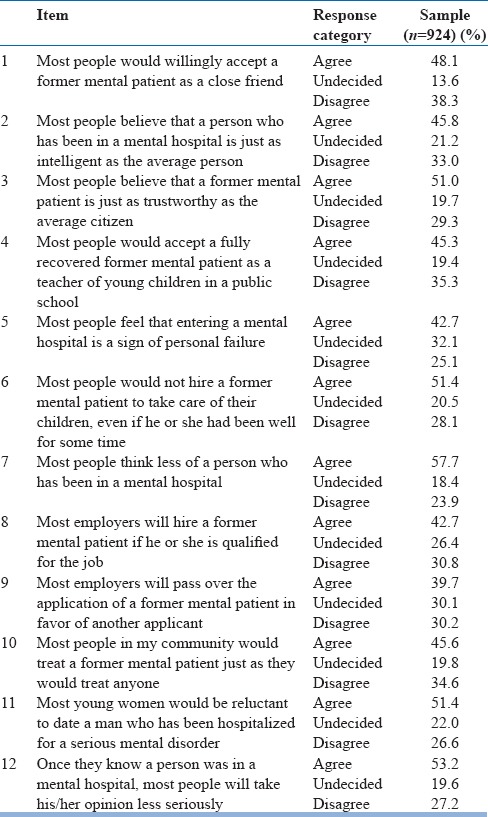

Table 2 displays single-item responses on the PDDS. In the following six out of twelve statements, participants’ answer properties present strong negative views toward people with mental illness: most people would consider a mental hospital stay as a sign of personal failure (5), most people would not hire a former mentally ill patient to take care of their children (6), most people would think less of a person who has been in a mental hospital (7), most employers will pass over the application of a former mental patient in favor of another applicant (9), most young women would be reluctant to date a man who had been hospitalized for a severe mental disorder (11), and finally that most people would take the opinion of a person they know less seriously if they had been to a mental hospital as a patient (12).

Table 2.

Individual item responses to the Perceived Discrimination and Devaluation Scale

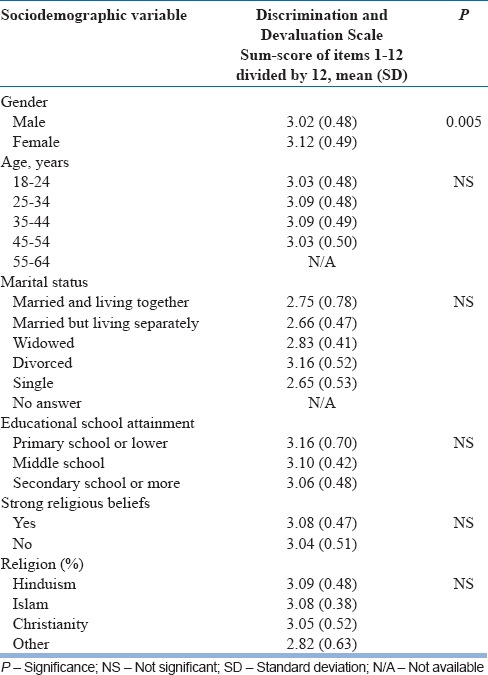

The results of the multiple linear regression are presented in Table 3. It displays the influence of each sociodemographic variable including gender, age, educational attainment, religion, and strength of religious belief on the level of perceived stigma, which is represented by a mean score. No significant effect of age, marital status, educational attainment, the strength of religious beliefs, or religion was detected. However, a significant effect for gender was found (B = 0.083, ß = 0.031, P = 0.008). Furthermore, results show that female participants reported higher levels of perceived stigma (SS = 3.12) compared to their male counterparts (SS = 3.03).

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression analysis showing the influences of demographic variables on mental illness on the Perceived Discrimination and Devaluation Scale mean score

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the association between perceived stigma toward mental illness and relevant sociodemographic factors of the respondents including gender, age, educational attainment, religion, and strength of religious beliefs. In line with a recent research about stigma toward mental illness in India and other developing Asian countries,[23,25,29] the current study found an overall high mean score for Link's PDDS. To weigh these rather high scores in the PDDS and ensure cross-cultural comparability, a comparison with Western countries is warranted. In 2014, a study using the PDDS in Germany reported largely diverging participant responses.[1] For instance, while in Germany, only 47% of respondents[1] endorsed that most people would think less of a person who had been in a mental hospital, the same assumption found 58% approval in our Indian sample; however, there was only 28.3% approval in a large urban sample in Vietnam.[21] Perceived stigma and public attitudes are linked to the availability of adequate treatment capabilities within a public mental health-care system. Even though most Western-European nations face challenges associated with a fragmented system of mental health-care providers and financial constraints,[29] due to better funding, the complex structure of mental health care to the population is arguably more effective in comparison to South and Southeast Asian low- and middle-income countries, such as Vietnam, Thailand, India, or the Philippines.[48,49,52] Due to a relatively small number of low-barrier institutions and health-care providers in comparison to most high-income countries, there is limited access to appropriate health services for a large portion of the Indian population.[16] Similarly, stigmatization toward individuals who have mental illness was reported to be higher in Asian than in Western countries.[20,48] As a consequence, mentally ill patients, especially those with a low socioeconomic status, in India, suffer from disparities in mental health-care services on different ecological levels of analysis. This discrepancy might account for higher rates of perceived stigma, stigma self-labeling, and perceived discrimination, which in turn may lead to delayed help-seeking behaviors and reluctance to utilize psychiatric treatment, if available. This is evidenced by how individuals suffering from a mental illness in India seem to be treated with less than adequate care due to barriers in adequate treatment resources, such as psychotherapy, community-based intervention, and support in the workplace.

In the present study, an association with gender was found, which is expressed in significantly higher perceived stigma toward mentally ill people among women. To interpret this finding, the cultural shaping of public attitudes regarding the role of women in the family, within the historical, political, and everyday lifeworld of India must be considered. One interpretation that could account for the discrepancy might lie within culturally coined dispositions of women experiencing social rejection, negative attitudes, and imposed gender roles. Such self-experiences might on the other hand enables an empathic personal understanding toward vulnerable population groups.

The results of the present study correspond to associated recent research concerning the role of gender in women's attitudes toward mental illness.[5,30,31] When general, societal, and cultural norms are considered, men and women display cultural shaped differences in perceiving illness across societies that also depend on the level of urbanity and socioeconomic status.[32] According to the current research, the importance of gender roles is linked to the effects of social, psychological, and material support by spouses, family, and friends on individual mental health,[33,34] since a functional support system can act as a buffer against adverse effects or stressful life events while lowering the risk of psychiatric disorders.[34] Research on gender roles within different societies suggests that women display a heightened overall demand for social support to maintain their psychological well-being.[33,34,35] However, a person's dependence on social support within larger families might also predetermine a higher vulnerability to emotional distress and mental disorders such as affective disorders, especially if confronted with perceived social rejection or when support systems disintegrate.[36] Hence, grounded in diverging social expectations, internalized experiences of social rejection may lead to women perceiving social support as lower.[34] Therewith, female participants might consider patients with mental illnesses, including themselves, as being too burdened and incapable of coping with stigma attached to mental illness, which thus results in even higher rates of perceived stigma.

This influence of gender roles on perceived stigma extends to other sociocultural dimensions. A study investigating the differences in internalized and externalized mental illness and gender stigma between mothers and fathers suggested that parents may experience gender-specific effects on parenting.[35] Considering the impact of cultural norms and gender stereotypes in the lifeworld of India, parenting remains in most social strata a predominantly female role. The transitional process in Indian societies has, especially in cities, shifted some of the caregiver responsibilities to men, gradually engendering an adjustment of social norms.[38] Nevertheless, close-knit family ties and hierarchies persist in India, and the immediate family remains the most important source of social support.

Respecting the familial constellations and gender dynamics in India, it is crucial to understand the cumulative effect of gender on perceived role expectations and stigmatization and discrimination in cases of perceived failure. In rural, but also large parts of urban India, the predominant role of married women is to function as a housewife, which impairs Indian women's capacity to build up and rely on an extensive social support system, compared to women in other countries.[37] In accordance, more than 60% of the female participants of this urban sample indicated their occupational status as “homemaker.” While the importance that is attributed to the role of a homemaker can generate pride and family recognition, the experienced caregiver burden and fear of failure, especially if affected by illness, also constitute risk factors for psychological distress. Being a “homemaker” may restrict Indian women's interaction outside of the familial realms and thus limits their access to a broader support system that is often available in working places.[34] These factors are in correlation with a limited external authority and independent decision-making capacity of women in most Indian societies and their often-subordinate role within the family hierarchy.[32] In accordance, recent studies revealed that the most common causes for attempted suicide among Indian women were marital and interpersonal problems, followed by psychiatric and physical illnesses.[39] Another study revealed higher levels of internalized stigma among women in India, which suggests that women may experience emotional distress even in the absence of immediate rejection or discrimination, but might refrain from seeking professional help. A possible interpretation for the higher levels of internalized stigma that is related to more reliance on functional social support systems may be associated with fear of social marginalization, rejection, abandonment, and domestic violence if stigmatized as a person with mental illness.[33] Continuing to facilitate the transition process of social and cultural norms as well as increasing legislative efforts in India may further strengthen women's autonomy and agency in the future.[43,53,54]

While the level of perceived stigma of mental illness in India is indicated to be high and the above-discussed potentially harmful effects cannot be rejected, studies on the prognosis of psychiatric disorders are also worth mentioning. India's social support system differs from that of the most Western countries. The concept of the family remains the most crucial institution of social support in India, with an emphasis on family integrity, loyalty, and family unity. This fundamental social concept applies strongly to the caretaking of family members affected by mental disorders. While it was not unusual for the mentally ill to experience rejection by their families after having been institutionalized in Western countries, in India, there has been a long tradition of involving not only close family members, but also extended kin with the treatment of mentally ill relatives. The importance of the role of a family when it comes to the treatment of those who have mental illness is emphasized when considering the relatively low number of mental health professionals in the country.[40]

Studies have shown positive influences of strong family support for those recovering from mental illness, which includes perceived moral support, practical support, and social motivation toward recovery.[41] It is also indicated that the influence of family regarding treatment results in less stigma[42] and in addition to that constitutes a factor for a more favorable social outcome and functioning. Finally, it has been shown that a broader distribution of the burden among larger and extended families results in a better capacity to adequately provide support for relatives of the mentally ill.[40]

Looking ahead and considering potential future research, it is worth mentioning an important political step that was reached with the Indian Mental Health Act,[50,51] implemented by the Government of India in April 2017. That progressive bill aimed to further strengthen persons affected by mental illness and their caregiver is destined to bring about a series of changes and treatment implication on a large-scale population level. The impact of this Mental Health Act on perceived discrimination and stigmatization, affecting the second largest population worldwide, will be a valuable subject of future population-based longitudinal studies. One of the main aims in the passing of the bill was to reduce the overall social stigma associated with mental illness in India.[45] Furthermore, effects of the law with regard to treatment, funding, and stigma are likely to also have a positive impact on the reputation of mental hospitals, which have suffered in comparison to the better funded, better staffed, and more up-to-date general hospital psychiatric units.[46,47] Therefore, it will be important to analyze how these legal changes that include a redefinition of mental illness, ensuring a right to access mental health care, decriminalizing attempted suicide, and giving more rights to persons who have a mental illness concerning their treatment and legal representation[43,44] will eventually reduce public, self, and structural stigma of persons and families affected by mental illness.[21]

Limitations

The present study encountered several limitations that ought to be considered in future research in this field. First, even though the present study achieved a large sample size of 920 participants, it cannot claim full representativeness for a population of 1.3 billion people. Second, while the sample included participants living in five metropolitan Indian cities representing different parts of the country, rural areas remained unattended. Future research could benefit from more varieties by providing insights into the effects of different cultural and societal norms by accounting for differences of urbanity. Third, further confounding variables with potential impact on the level of perceived stigma, such as household size, marital status, or familiarity with mental illness, cannot be ruled out. Finally, a moderate Cronbach's alpha (α = 0.476) may be related to the heterogeneous sample regarding the geographic location in India, language, and overall cultural background, given India's enormous size and diversity. Fourth, the study has been conducted by a team of ten authors from a diverse cultural background, among these three authors of Indian descent (AZ, AM, and AT) with training or researching at least part time in India. All the other authors have conducted several peer-reviewed studies regarding public attitudes toward psychiatry in countries of diverse cultural, religious, and social background. Nonetheless, the research team is currently collaborating with the Asian Institute of Public Health, Odisha, and therewith more researchers in India to assess attitudes toward mental health illness in more diverse way, especially in rural settings of India, to obtain an even better comparative understanding of the field.

CONCLUSION

The present study analyzed data from five metropolitan cities in India regarding the perceived stigma and discrimination of mental illness in India, thereby explicitly accounting for influential sociodemographic factors. The analysis revealed a significant influence of gender on the perceived stigma of mental illness, with higher levels of perceived stigma among female participants. As a next step, awareness programmes related to issues such as gender and family roles, but also public support systems, should be implemented. Additionally, increasing awareness about mental health as well as the integration of mental health into the primary health care system resemble measures that could reduce stigmatization and facilitate mental healthcare utilization within the framework of the Indian Mental Health Act.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study is part of the dissertation project of Mr. Aron Zieger, M. Sc. and Mr. Kerem Böge, M. Sc. We wish to thank all participants who agreed to take part in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Carta MG, Schomerus G. Changes in the perception of mental illness stigma in Germany over the last two decades. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:390–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso J, Buron A, Rojas-Farreras S, de Graaf R, Haro JM, de Girolamo G, et al. Perceived stigma among individuals with common mental disorders. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:180–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. Stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental disorders: Findings from an Australian national survey of mental health literacy and stigma. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:1086–93. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.621061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Continuum beliefs and stigmatizing attitudes towards persons with schizophrenia, depression and alcohol dependence. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209:665–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook TM, Wang J. Descriptive epidemiology of stigma against depression in a general population sample in Alberta. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littlewood R. Cultural variation in the stigmatisation of mental illness. Lancet. 1998;352:1056–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A, Sartorius N. Stigma: Ignorance, prejudice or discrimination? Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:192–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lien YJ, Kao YC, Liu YP, Chang HA, Tzeng NS, Lu CW, et al. Relationships of perceived public stigma of mental illness and psychosis-like experiences in a non-clinical population sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:289–98. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0929-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zelaya CE, Sivaram S, Johnson SC, Srikrishnan AK, Suniti S, Celentano DD, et al. Measurement of self, experienced, and perceived HIV/AIDS stigma using parallel scales in Chennai, India. AIDS Care. 2012;24:846–55. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.647674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans-Lacko S, Brohan E, Mojtabai R, Thornicroft G. Association between public views of mental illness and self-stigma among individuals with mental illness in 14 European countries. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1741–52. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright ER, Gronfein WP, Owens TJ. Deinstitutionalization, social rejection, and the self-esteem of former mental patients. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:68–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siu BW, Chow KK, Lam LC, Chan WC, Tang VW, Chui WW, et al. A questionnaire survey on attitudes and understanding towards mental disorders. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2012;22:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenfield S. Labeling mental illness: The effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. Am Soc Rev. 1997;62:660. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rusch N, Abbruzzese E, Hagedorn E, Hartenhauer D, Kaufmann I, Curschellas J, et al. Efficacy of coming out proud to reduce stigma's impact among people with mental illness: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:391–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.135772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59:614–25. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, et al. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Summary. Bengaluru (IN): National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences; 2016. Supported by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinha SK, Kaur J. National mental health programme: Manpower development scheme of eleventh five-year plan. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:261–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.86821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raja S, Wood SK, de Menil V, Mannarath SC. Mapping mental health finances in Ghana, Uganda, Sri Lanka, India and Lao PDR. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2010;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saxena S, Sharan P, Saraceno B. Budget and financing of mental health services: Baseline information on 89 countries from WHO's project atlas. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2003;6:135–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauber C, Rössler W. Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:157–78. doi: 10.1080/09540260701278903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Link BG, Schomerus G. Public attitudes regarding individual and structural discrimination: Two sides of the same coin? Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Preferences of the public regarding cutbacks in expenditure for patient care: Are there indications of discrimination against those with mental disorders? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:369–77. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kermode M, Bowen K, Arole S, Pathare S, Jorm AF. Attitudes to people with mental disorders: A mental health literacy survey in a rural area of Maharashtra, India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:1087–96. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zieger A, Mungee A, Schomerus G, Ta TM, Dettling M, Angermeyer MC, et al. Perceived stigma of mental illness: A comparison between two metropolitan cities in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:432–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Government of India. Census of India 2011. India(IN): 2011. pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. Am Soc Rev. 1989;54:400. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sartorius N, Kuyken W. Translation of Health Status Instruments. In: Orley J, Kuyken W, editors. Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives. Springer, Berlin: Heidelberg; 1994. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salize HJ, Rössler W, Becker T. Mental health care in Germany: Current state and trends. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257:92–103. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0696-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swami V. Mental health literacy of depression: Gender differences and attitudinal antecedents in a representative British sample. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulder R, Pouwelse M, Lodewijkx H, Bolman C. Workplace mobbing and bystanders’ helping behaviour towards victims: The role of gender, perceived responsibility and anticipated stigma by association. Int J Psychol. 2014;49:304–12. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geary C, Parker W, Rogers S, Haney E, Njihia C, Haile A, et al. Gender differences in HIV disclosure, stigma, and perceptions of health. AIDS Care. 2014;26:1419–25. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.921278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soman S, Bhat SM, Latha KS, Praharaj SK. Do life events and social support vary across depressive disorders? Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39:316–22. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.207334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lacey M, Paolini S, Hanlon MC, Melville J, Galletly C, Campbell LE, et al. Parents with serious mental illness: Differences in internalised and externalised mental illness stigma and gender stigma between mothers and fathers. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225:723–33. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLeish J, Redshaw M. Mothers’ accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:28. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dhawan N. Women's role expectations and identity development in India. Psychol Dev Soc J. 2005;17:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabri B, McFall AM, Solomon SS, Srikrishnan AK, Vasudevan CK, Anand S, et al. Gender differences in factors related to HIV risk behaviors among people who inject drugs in north-east India. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deshpande SS, Kalmegh B, Patil PN, Ghate MR, Sarmukaddam S, Paralikar VP, et al. Stresses and disability in depression across gender. Depress Res Treat. 2014;2014:735307. doi: 10.1155/2014/735307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu SH, Srikrishnan AK, Zelaya CE, Solomon S, Celentano DD, Sherman SG, et al. Measuring perceived stigma in female sex workers in Chennai, India. AIDS Care. 2011;23:619–27. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avasthi A. Preserve and strengthen family to promote mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:113–26. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.64582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aldersey HM, Whitley R. Family influence in recovery from severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51:467–76. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9783-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jadhav S, Littlewood R, Ryder AG, Chakraborty A, Jain S, Barua M, et al. Stigmatization of severe mental illness in India: Against the simple industrialization hypothesis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:189–94. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao GP, Math SB, Raju MS, Saha G, Jagiwala M, Sagar R, et al. Mental health care bill, 2016: A boon or bane? Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:244–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.192015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deepalakshmi K. All you Need to Know about the Mental Healthcare Bill. The Hindu. 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 25]. Available from: http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/all-you-need-to-know-about-the-mental-healthcare-bill/article17662163ece .

- 45.Kedia S. The Ambitious Mental Healthcare Bill is a Step Closer to a Progressive India. 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 25]. Available from: http://www.Yourstory.com .

- 46.Nizamie SH, Goyal N. History of psychiatry in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S7–S12. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krishnamurthy K, Venugopal D, Alimchandani AK. Mental hospitals in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:125–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ta TM, Zieger A, Schomerus G, Cao TD, Dettling M, Do XT, et al. Influence of urbanity on perception of mental illness stigma: A population based study in urban and rural Hanoi, Vietnam. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;62:685–95. doi: 10.1177/0020764016670430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ta TMT, Böge K, Cao TD, Schomerus G, Nguyen TD, Dettling M, et al. Public attitudes towards psychiatrists in the metropolitan area of Hanoi, Vietnam. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;32:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duffy RM, Kelly BD. Concordance of the Indian mental healthcare act 2017 with the World Health Organization's checklist on mental health legislation. Int J Mental Health Syst. 2017;11:48. doi: 10.1186/s13033-017-0155-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ministry of Law and Justice. The Mental Healthcare Act 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 07]. Available from: http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Mental%20Health/Mental% 20Healthcare%20Act,%202017.pdf .

- 52.Vuong DA, Van Ginneken E, Morris J, Ha ST, Busse R. Mental health in Vietnam: Burden of disease and availability of services. Asian J Psychiatr. 2011;4:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shidhaye R, Kermode M. Stigma and discrimination as a barrier to mental health service utilization in India. Int Health. 2013;5:6–8. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihs011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knodel J, Loi VM, Jayakody R, Huy VT. Gender roles in the family. Asian Popul Stud. 2005;1:69–92. [Google Scholar]