Abstract

Context:

Mental health disorders are an important factor contributing to the global burden to disease. Less than 1% of the health budgets in 62% of developing nations and 16% of developed nations are spent on mental health services. The availability of mental health rehabilitative services remains minimal.

Aims:

This study aims to find the effectiveness of a new low-cost psychosocial rehabilitation model.

Setting and Design:

The study was conducted at a rehabilitation center. An interventional follow-up study was designed.

Materials and Methods:

A new low-cost psychosocial rehabilitative model was employed for 6 months for persons residing at a rehabilitation center. The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) instrument, WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) 2.0, and WHO (Five) Well-Being Index would be scored before and after the intervention.

Statistical Analysis:

The differences between the scores were analyzed using paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed rank test, whichever is applicable. P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results:

Sample size was 110. 29.1% were rehabilitated and 68.2% remained at the rehabilitation center at 6 months. The pre- and post-test scores using the new model showed improvement in the scores. The mean scores for WHO-BREF, WHO-5 score, WHODAS-2 score were 73.2, 51.14, and 20.34, respectively. On follow-up, the scores improved to 82.6, 67.09, and 15.96, respectively.

Conclusions:

The low-cost psychosocial rehabilitative model was found to be effective. This could serve as a model not only for other similar centers in India and but also for other low- and middle-income group countries.

Keywords: Global burden mental illness, low-cost psychosocial Rehabilitation, rehabilitative model for LMIC

INTRODUCTION

Mental health disorders are an important factor contributing to the global burden to disease. A recent study suggests that the global burden of mental illness is 32.4% of years lived with disability and 13% of disability-adjusted life years.[1] As part of the national mental health survey in India, it is estimated that the morbidity of mental health disorders excluding tobacco use disorders is 10.6%. The lifetime prevalence of mental health disorders in India is 13.7%.[2,3]

Despite this global burden of mental illness, the financing for mental health care remains minimal. Less than 1% of the health budgets in 62% of developing nations and 16% of developed nations are spent on mental health services. It should also be noticed that the expenditures are mostly concentrated on psychiatric hospital and tertiary care centers rather than community-based services.[4]

Primarily, the financing for health services in India is done by the State Government. The government spends only 1.2% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on health and out of pocket expenses count to 58% of the total health expenditure.[5] About 75% of mental health services in India were provided by the private sector.[6] Therefore, it is only safe to assume that the private sector plays a pivotal role in reducing the mental health gap in India. Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) have a particular reach to persons with severe mental health disorders, particularly in rural areas. Despite this, the availability of mental health rehabilitative services remains minimal. As part, a survey conducted in 12 states across India, only 69 NGOs were reported to be functioning for mental health.[3]

Pushpagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, Thiruvalla, India, is postgraduate training center catering to an urban/semiurban population. As part of our community psychiatry project, we have been actively involved with an NGO which runs a residential rehabilitative center dedicated to support persons with mental health disorders. The financial burden and constraint make it difficult for this residential care rehabilitative program to function smoothly without support. This outreach center “Mariasadanam” is located at Palai, 50 km away from the institute.

The center is run by an NGO, and its personnel have limited training in mental health rehabilitation. The NGO comprises of a total of 15 people from the administrator to the security guard who cater to the needs of 335 individuals at the rehabilitation center. We have devised an innovative low-cost model for rehabilitative therapy with the existing finances and human resources to conduct such a service. In this study, we explain the model and also find the clinical benefits of this model so that it can be replicated in other centers across India as well as other low- and middle-income group countries (LMICs) for the benefit of persons with mental health disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at an NGO designated as our community outreach project.

Scientific committee and ethical committee clearance were taken before the study. Informed consent was taken both from the patient and the NGO before initiating the study.

Our aim was to find the effectiveness of a low-cost psychosocial rehabilitation model.

Individuals with a total duration of psychiatric illness for >2 years and residing at the rehabilitation center were taken for the study. Residents who had intellectual disability, speech or hearing impairment, physical disability or who were not cooperative were not taken for the study as it would affect the scores of the scales applied.

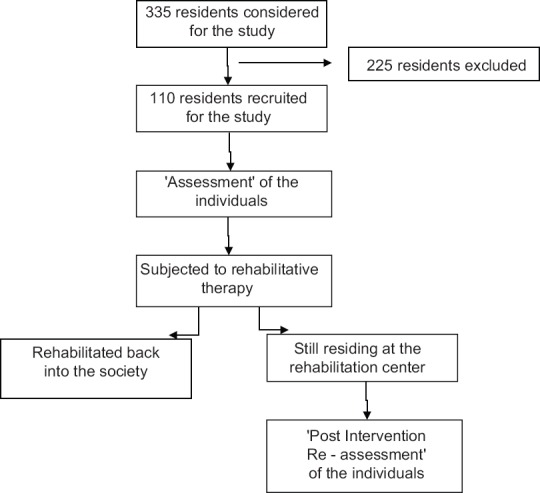

The rest of the methodology can be divided into three phases

Assessment Phase

Intervention Phase

Postintervention Re-Assessment Phase.

Assessment phase

An initial assessment of every individual would be done which would assess each individual's area of expertise. Individuals from various fields of vocation were identified. We had Security guards, carpenters, accountants, manual laborer, cooks, etc. Individuals who knew to sing, dance, act, and play musical instruments were also noted. Assessment would be done to find how well and fit they were to undertake these activities.

A general questionnaire, World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) instrument, WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) 2.0, and WHO (Five) Well-Being Index would be would be scored and the results would be recorded.

The general questionnaire enquired about the socio-demographic details of the individual along with their clinical profile.

The WHOQOL-BREF produces a profile with four domain scores and two individually scored items about an individual's overall perception of quality of life and health. The four domain scores are scaled in a positive direction with higher scores indicating a higher quality of life.[7,8]

WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) was developed by the WHO for assessment and classification of disability. The 12-item interviewer-administered version was used. The 12-item version explains 81% of the variance of the more detailed 36-item version.[9]

WHO (Five) Well-being Index is calculated by totaling the figures of five answers to assess the quality of life. The raw score ranges from 0 to 25, 0 representing worst possible and 25 representing the best possible quality of life.[10]

Intervention phase

“Manoranjini” entertainment programs-radio programs would be aired through the speakers over the rehabilitation center. Drama and stage shows – individuals volunteered to can act in plays/dramas and also used the stage to showcase their talents such as singing and playing musical instruments. The stage shows were also used as fundraisers for the NGO.

Cooking unit was established were the inmates cooked for themselves under supervision. An inmate was assigned as the chief cook who would direct the other inmates. 4–5 individuals who knew to cook well supported the chief cook while other helped in cutting and cleaning raw materials and in other chores of the kitchen.

Candle making units – the candles would then be sold by the inmates themselves on roadside stalls on days of the Holy Mass and other auspicious days at nearby Churches. Other materials made were doormats, wooden hair clips, flower stands, kitchen spoons, and rice cake (“Putt”– a local breakfast) vessels.

Washing unit – Washing machines and drying areas were provided. The inmates were encouraged to wash their own clothes at the washing unit. Barber unit – inmates who were previously employed as barbers would trim/cut/shave the other inmates. Some of the inmates were also recruited as security personals given charge of security within the rehabilitation center. They were overlooked by a chief security officer.

A tailoring unit was also established in the rehabilitation center where a chief trainer was selected among the inmates. Inmates who had experience using a sewing machine and others who were willing to learn were selected and taught tailoring. The garments would then be sold to the retailers or directly to customers at a nominal price.

The occupational therapist and social workers would guide the inmates. Inmates who had previous experience in similar works and those who were interested were selected initially. They would then be entrusted to teach other inmates once they finish their training.

Postintervention re-assessment phase

After 6 months of intervention, the inmate population was screened to find out how many individuals were rehabilitated into the society. Residents who were not rehabilitated after 6 months were re-assessed.

The individuals who remained at the Rehabilitation Centre after 6 months of rehabilitative therapy would be re-assessed with WHOQOL-BREF instrument, WHO-DAS 2.0, and WHO (Five) Well-Being Index. This would enable us to find out if the therapy had brought about any changes in these individuals.

The raters were postgraduate residents in psychiatry with at least 6 months of training. The raters were blind to the previous scores of the individuals.

Statistical analysis

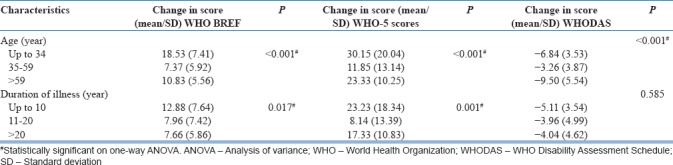

The data analysis was done by a statistician who was unaware of the identity and rehabilitative status of the individual. The baseline WHO-BREF, WHO-5, and WHODAS-2 scores were found out for each participant before enrolling them into the structured rehabilitation program. At the end of 6 months, the same scores were found out for those remaining in the program. The differences in scores were analyzed using paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed rank test, whichever is applicable. The changes in scores with age of the patient and duration of illness were assessed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant [Table 5].

Table 5.

Factors affecting changes in scores

Data Collection Scheme

RESULTS

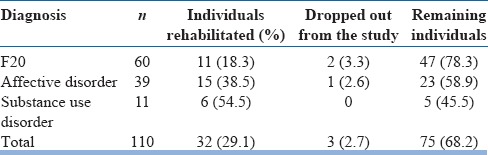

A total of 110 patients were included for the study. As per the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision research criteria 60 of the inmates were diagnosed to have schizophrenia, 39 with affective disorders and 11 with mental and behavioral disorders due psychoactive substance use. At the end of 6 months, we were able to rehabilitate 32 persons back into the society. Out of which were 8 persons with schizophrenia, 15 persons with affective disorder, and 9 persons with substance use. Three individuals were dropped out of the study as they were shifted to a hospital for the treatment of physical comorbidities for >10 weeks [Table 1].

Table 1.

Diagnosis of participants involved in the study

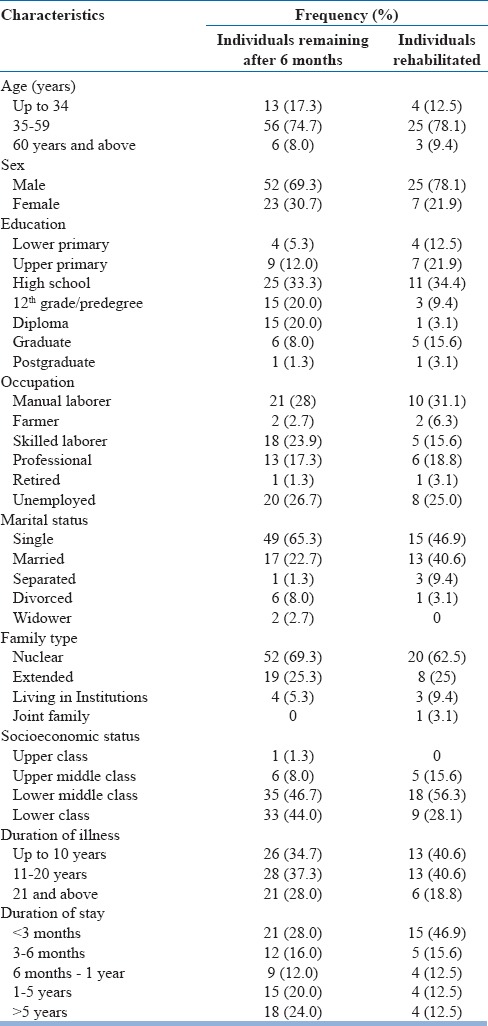

We compared the socio-demographic profile of individuals who were rehabilitated and ones who were still remaining at the center postintervention. About 74.7% of the persons who remained after 6 months of intervention were between the age of 35 years and 59 years, followed by the age below 34 years 69.3% were males and 30.7% were females. There were no illiterates and only 17.3% of the individuals were educated below the level of high school. About 23.9% of the persons were skilled laborers, 17.3% were professionals, and 26.7% remained unemployed. Majority of the individuals were unmarried (65.3%). 69.3% hailed from nuclear families majority of the individuals living at the rehabilitation center had a total duration of illness of more 10 years (65.3%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Baseline sociodemographic and disease characteristics

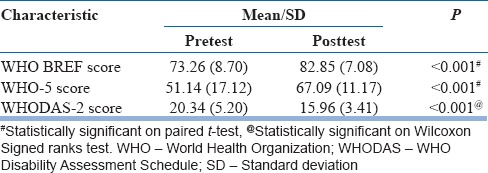

The scales were then used again to reassess the remaining individuals at the rehabilitation center. The WHO-BREF scores showed a significant improvement after 6 months of rehabilitation. The WHO 5 scores also showed comparable results. The disability index of these individuals had also improved which is reflected in the decrease in scores after 6 months of intervention. All the results were found to be statistically significant with P < 0.001 for WHO-BREF and WHO-5 using the paired t-test. The significance for the WHODAS score was found using Wilcoxon's Signed ranks test [Table 3].

Table 3.

Scores before and 6 months after starting the rehabilitation program

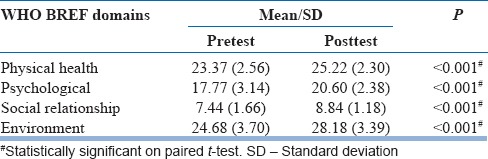

The WHO-BREF questionnaire can be divided under different domains. Although all domains have shown significant improvement in the scores after 6 months of intervention, the least improvement was seen in social relationship domain. The results were shown to be statistically significant with a P = 0.001 using the paired t-test for comparing the means of the scores before and after intervention [Table 4].

Table 4.

Change in various domains of World Health Organization BREF score

DISCUSSION

Rehabilitation remains an important aspect of treatment for individuals with long-standing psychiatric illness, and there is no doubt they are effective. Although different models and strategies are available throughout the literature, most of the studies have been concentrated in developed countries. Studies conducted in developing countries are usually done in Centre's where adequate funding and workforce are available.

A similar study at another centre in South India had conducted a retrospective study at their half-way home to evaluate the effectiveness of their rehabilitative technique. The study showed promising results as the residents had improved on a 5-point rating scale. In this light, a prospective study for a low-cost rehabilitative program was required.[11]

Evaluation of treatment costs has become an important factor in deciding treatment policies and strategies.[12]

These techniques would lower the economic burden and also help reduce the cost of illness mental health disorders The improvement in quality of life and reduction in disability status in individuals have been shown to be statistically significant after 6 months of intervention thereby helping in early discharge of the inmates from the rehabilitation center. Early discharge, reduced treatment costs, improvement in quality of life, reduction in disability status, and early rehabilitation will have a positive effect in reducing the burden of disease in the society.

Associations with NGOs have always been suggested as a strategy to reduce the mental health gap.[13,14] Our results shed light into the fact that rehabilitative techniques can be employed in a Centre even when there are minimum resources. We were able to rehabilitate 32 individuals successfully back to their homes. The individuals who remained at the rehabilitation center after the intervention phase showed significant improvement in their quality of life and disability status.

This is the first study from India where the above low-cost model for psychosocial rehabilitation has been studied with the total involvement of NGOs under the supervision our supervision. Kerala is a model for healthcare but is lagging behind in mental health care especially manifested by high suicide rates.[15] High literacy of people and mental health sophistication has been put to the best use in this study which is the first of its kind from the state.

This could serve as a model not only for other similar centers in India and but also for other LMIC across the world where mental health provisions are poor and mental health professionals are inadequate.

Limitations

Sampling procedures were not randomized. A control group for comparing the results of the intervention would have been better. Even though the raters were unaware of the previous scores of the patient, they were not blind to the fact that the particular individual was on the 3rd phase (postassessment re-evaluation phase) of the study.

The patients were also on pharmacotherapy while being subjected to the psychosocial intervention. The inmates were reviewed periodically by the Psychiatrist. The residents at the rehabilitation center were on appropriate pharmacotherapy for at least 3 months before the initiation of interventions. Hence, we can conclude with reasonably that the rehabilitative techniques were beneficial for the individuals.

Vocational rehabilitation was focused more in the model. All the rehabilitative techniques employed were group activities which required the individuals to cooperate, help, and support each other. This helped them build friendships among themselves and also teach them workplace etiquettes. This experience would mold their social skills for better functioning.[16]

Thirty-two individuals were rehabilitated back to their homes before the postintervention re-evaluation phase; hence, we were not able to quantify and document their improvement.

Future research

A cost-effective cost-benefit analysis of the project would be beneficial in providing more insight regarding the monetary aspect.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:171–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, Mehta RY, et al. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Prevalence, patterns and outcomes. Bengaluru: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, NIMHANS Publication No. 129; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Summary. [Last accessed on 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.nimhans.ac.in/sites/default/files/u197/National%20Mental%20Health%20Survey%20-2015-16%20Summary_0.pdf .

- 4.WHO. The Mental Health Context-Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ninety-Third Report on Demands for Grants 2016-17 (Demand No. 42) of the Department of Health and Family Welfare, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. [Last accessed on 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www. 164.100.47.5/newcommittee/reports/EnglishCommittees/Committee%20on%20Health%20and%20Family%20Welfare/93.pdf .

- 6.Executive Summary Report of the National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, Ministry of Health ‘ Family Welfare, Government of India. 2005. Sep, [Last accessed on 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/macrohealth/action/Report%20of%20the%20National%20Commission.pdf .

- 7.Nelson CB, Lotfy M. WHO (MNH/MHP/997) Geneva: WHO; 1999. The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. [Last accessed on 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/substanceabuse/researchtools/en/englishwhoqol.pdf .

- 9.World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) 2001. [Last accessed on 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/icidh/whodas/index.html .

- 10.The WHO-5 Well-Being Index (1998 Version) [Last accessed on 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: https://www.psykiatri-regionh.dk/who-5/Pages/default.aspx .

- 11.Chowdur R, Dharitri R, Kalyanasundaram S, Suryanarayana RN. Efficacy of psychosocial rehabilitation program: The RFS experience. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:45–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.75563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grover S, Avasthi A, Chakrabarti S, Kulhara P. Overview and emerging trends. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:205–10. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.43052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacob KS. Community care for people with mental disorders in developing countries: Problems and possible solutions. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:296–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.4.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thara R, Patel V. Role of non-governmental organizations in mental health in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S389–95. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerala State Mental Health Authority. Suicides in Kerala. [Last accessed on 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.ksmha.org/Suicide2014.pdf .

- 16.Rössler W. Psychiatric rehabilitation today: An overview. World Psychiatry. 2006;5:151–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]