Abstract

Context: Biofortification of staple crops is a promising strategy for increasing the nutrient density of diets in order to improve human health. The willingness of consumers and producers to accept new crop varieties will determine whether biofortification can be successfully implemented. Objective: This review assessed sensory acceptance and adoption of biofortified crops and the determining factors for acceptance and adoption among consumers and producers in low- and middle-income countries. Data sources: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched for published reports. Unpublished studies were identified using an internet search. Study selection: From a total of 1669 records found, 72 primary human research studies published in English or Spanish met the criteria for inclusion. Data extraction: Data were extracted from each identified study using a standardized form. Results: Sensory acceptability (n = 40) was the most common topic of the studies, followed by determinants of acceptance (n = 25) and adoption (n = 21). Of crops included in the studies, sweet potato and maize were the most studied, whereas rice and pearl-millet were the least investigated. Overall, sensory acceptance was good, and availability and information on health benefits of the crops were the most important determinants of acceptance and adoption. Conclusions: Changes to the sensory qualities of a crop, including changes in color, did not act as an obstacle to acceptance of biofortified crops. Future studies should look at acceptance of biofortified crops after they have been disseminated and introduced on a wide-scale.

Keywords: acceptability, adoption, biofortified crops, micronutrients, nutrition-sensitive agriculture

INTRODUCTION

Biofortification of staple crops is a promising strategy for increasing the micronutrient density of diets in order to improve human health.1 The Copenhagen consensus in 2008 and the Lancet series on maternal and child malnutrition published in 2013 identified biofortification as one of the key interventions to reduce micronutrient deficiencies in low- and middle-income countries.2 The strategy was implemented for the first time in the mid-1990s3; for example, orange-fleshed sweet potato (OFSP) was used to reduce vitamin A deficiency in Guatemala.4 Since then, biofortification has received much larger financial investment through the HarvestPlus program, which was initiated in 2003 and has funded research projects and implementation programs on biofortification around the world.5 Biofortification is not, however, only being applied by HarvestPlus; it has also became part of government strategies and is used by local plant breeding organizations.6

Biofortification mainly focuses on the breeding of staple crops, such as maize, rice, beans, potatoes, millet, and cassava. Three different methods—conventional or classic plant breeding, agronomic approaches such as soil-fertilization, and genetic engineering—are used, with the majority of biofortification done by conventional plant breeding.6 Agronomic approaches are useful when the mineral concentration of the soil is a limiting factor for increased micronutrient concentration of the crop. Direct evidence of improved human health from biofortification through agronomic approaches and genetic engineering is lacking.7,8 Staple crops are targeted by biofortification efforts because they often have low micronutrient density and are consumed in large quantities by a large proportion of resource-poor populations.1 Therefore improvement of the nutrient value of staple crops versus other crops is believed to have a large impact for those population groups that are difficult to reach with other interventions and is a valuable complement to direct nutrition interventions, like supplementation. The success of biofortification as a strategy largely depends on the willingness of consumers and producers to accept the newly bred crop varieties.6 Adoption of biofortified crops by producers will largely depend on factors such as yield, disease resistance, drought tolerance, and marketability. For consumers, the change in sensory traits in biofortified crops can be an important factor that influences adoption; for example, in provitamin A–rich crops, such as OFSP, orange maize, and yellow cassava, there will be a change in color.

The factors that determine acceptance (reflecting the perception among producers and consumers that an intervention is agreeable9) and adoption (reflecting the intention, initial decision, or action to try a new intervention9) of biofortified crops can be identified using a variety of distinct methods. Sensory studies, including preference testing, give information on sensory attributes that influence consumer acceptance. Cross-sectional questionnaire-based surveys reveal attitudes, constraints, and facilitators of consumer or producer acceptance and adoption of biofortified varieties. Effectiveness studies can show whether biofortified crops are acceptable and are adopted over a certain period of time, often comparing intensive and less intensive interventions. Experimental auctions can elucidate the willingness of consumers to pay for a biofortified crop compared with, for example, a locally available, nonbiofortified crop, indicating the possibility of a premium or the need for a discount when introducing biofortified varieties to ensure acceptance.10

Factors influencing acceptance of biofortified crops vary largely by type of crop and country but also by characteristics of consumers, such as age, sex, socioeconomic status, and being a disliker or liker of biofortified crops. Children under 5 years of age and women of childbearing age are considered most at risk of micronutrient deficiencies and are, therefore, often specifically targeted by nutrition interventions.11

For this systematic review, studies were retrieved and aspects related to acceptance and adoption of biofortified crops in low- and middle-income countries were summarized and assessed. Key determinants that constrain or facilitate the implementation of this strategy were also identified in order to maximize the impact of ongoing and future biofortification programs.

SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE SEARCH

A systematic literature review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA Statement checklist and reporting guidelines12 to identify studies on the acceptance and adoption of biofortified crops. PICO criteria were established to identify the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). A systematic search of the literature was conducted in April 2016 using the electronic databases PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science with combinations of key words related to the 2 key topics of (1) Biofortification and (2) Acceptance OR Adoption (Table 2). Both key topics comprised several search terms in groups, and each group was made up of synonyms within a search term divided by using the Boolean expression “OR,” whereas groups were combined by using “AND.” For the final search, the key topics were combined with these groups and both abstracts and titles of articles were searched, except for those in Web of Science, where only the title was searched. This resulted in 3 database sets with article titles, which were screened independently by the authors A.M.B. and E.F.T. for relevance. When there were doubts about relevance or disagreement between reviewers, an article received the benefit of the doubt and was included in the next step of abstract review.

Table 1.

PICOS criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies

| Parameter | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Humans | Animals, cell cultures |

| Intervention | Biofortified staple crops with micronutrients | Biofortified nonstaple crops, improved quality protein maize |

| Comparator | Different biofortified crops or standard “control” crop | None |

| Outcomes | Acceptance or adoption of biofortified crops | Efficacy or effectiveness without acceptance or adoption |

| Study design | Cross-sectional surveys, randomized controlled efficacy studies, or effectiveness studies | None |

Table 2.

Key topics with search terms used in systematic search strategy

| Biofortification |

Acceptance and Adoption | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 |

| Biofort* | Crop* | Iron | Accept* |

| Bio-fortification | Food | Zinc | Willingnes* |

| Orange 5 | Maize | Provitamin* | Choice |

| Yellow | Cassava | Pro-vitamin* | Sensory |

| GMO | Potato | Carot* | Preference |

| GM | OFSP | Beta-carot* | Adoption |

| Sweet | Betacarot* | Impact | |

| Millet | Vitamin A | Uptake | |

| Pearl | Folate | Production | |

| Rice | Selenium | ||

| Bean | Phytat* | ||

| Sorghum | Phytic* | ||

| Lentils | Folic | ||

Abbreviations: GM, genetically modified; GMO, genetically modified organism; OSFP, orange flesh sweet potato.

Abstracts of the initially selected articles were reviewed for exclusion criteria by all authors. These criteria were the following: not about biofortification with micronutrients; not a human study; not conducted in a low- and middle-income country; not a study of a staple crop (as defined in the search strategy: maize, cassava, sweet potato, potato, pearl millet, bean, sorghum, rice); not in English or Spanish; no mention of acceptability; and no original research.

The full text of all remaining publications was reviewed, with the review work divided among the authors. When data suitable for inclusion were found, data were extracted manually into a matrix and cross-checked by all authors. Disagreements or doubts were resolved by consensus.

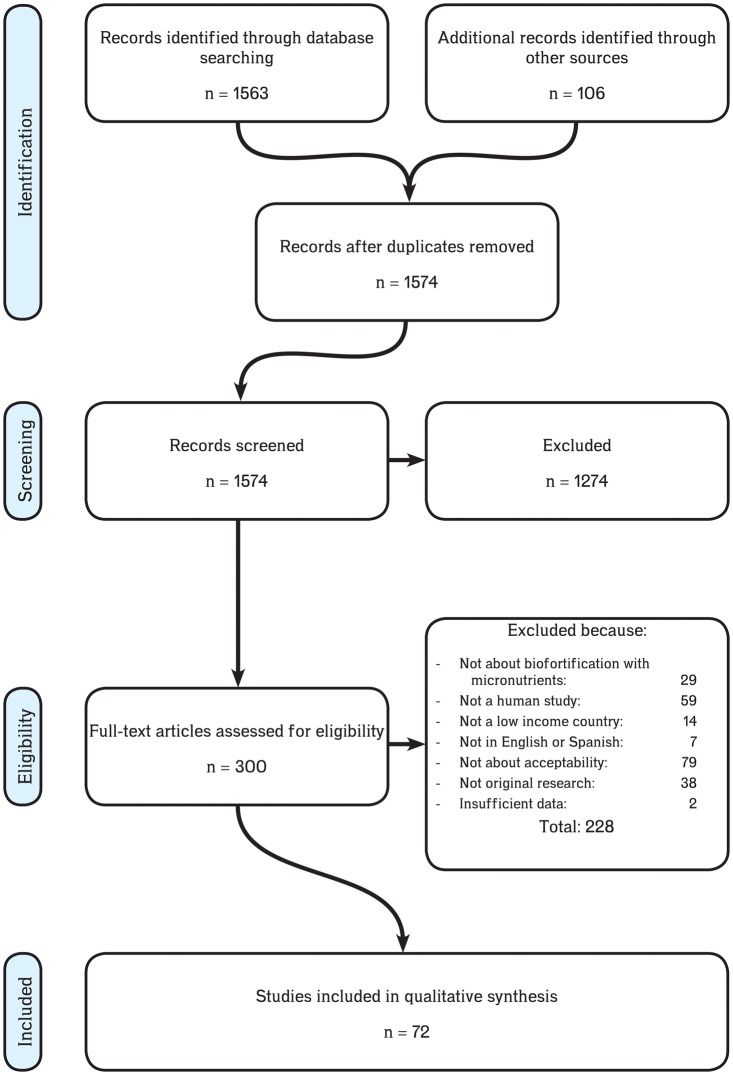

In addition to the systematic literature search, key experts on the topics were contacted regarding relevant papers, unpublished work on the topic, and project descriptions available on the Internet. A “snowball” search, also known as an “other literature search,” whereby reference lists of papers were hand-searched to ensure that all relevant studies were identified, was also conducted. A similar data extraction procedure to that described above was used for this set of papers. Duplicates were removed. Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of the literature search process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search process.

RESULTS

In total, 1563 records from the systematic database search and 106 records from the other literature search were found. After initial screening of the 1669 records, the full texts of 300 records were assessed for eligibility. A total of 72 studies were found to be eligible and were included in the review. Thirty-five of the selected studies were not found in the systematic database search: 8 were published in Spanish in nonindexed journals, 15 were part of progress reports by organizations or provided as personal communication, 4 were nonpublished conference abstracts, and 3 were nonindexed master’s theses. Study populations mostly consisted of heads, spouses, or members of rural households, 18 years of age or older, either recruited randomly or at convenience around market places or shopping areas. Fourteen studies included children of different age ranges,13–25 (Tomlins et al., HarvestPlus, personal communication, 2016) and 1 study specifically targeted pregnant women.26 Seven studies were conducted among university students.27–33 Four studies included a panel trained to recognize and differentiate sensory attributes.14,34–36

Sensory acceptability

A total of 40 studies on the sensory acceptability of biofortified crops were identified (Table 313–21,26–28,34–57) and these involved various staple foods: sweet potato (n = 15), beans (n = 9), maize (n = 7), rice (n = 4), cassava (n = 4), and pearl millet (n = 1). Twenty-four studies were conducted in Africa, 12 were conducted in Latin America, and 4 were conducted in Southeast Asia. The most commonly used method was a sensory attribute study that used hedonic scales varying from 4 to 9 points; other methods used were structured interviews,37 discrimination testing,20,38,39 and preference testing.16,20,26,38,40 In some studies, especially those including children and illiterate populations, facial hedonic scales were used (n = 13). In only 2 studies, the sensory evaluation was done after several days of testing of the biofortified product crop as part of a meal prepared at home.41,42

Table 3.

Sensory evaluation of biofortified crops by consumers in low- and middle-income countries

| Reference | Country | Study Population | Method and Study Design | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet potato | |||||

| Tomlins et al. (2007)19 | Tanzania |

|

Sensory attributes study (100-mm unstructured scale, interviews, and 7-point hedonic facial scale) for color, pumpkin flavor, texture, starchiness, and sweet taste of 30–50 g of cooked OFSP and PFSP | Mothers liked OFSP better than PFSP, but children liked both. Clusters with different preferences for different characteristics were observed | New cultivars should be screened; mothers have probably more influence on introduction than children |

| Low et al. (2008)37 | Mozambique |

|

Structured interview and ranking of key characteristics of bread buns with 38% of white wheat flour replaced by boiled and mashed OFSP (golden bread) | Preference for golden bread because heavier texture, superior taste, and attractive golden appearance. With 47 consumers who purchased golden bread, preference was 98% because of color, 85% because of taste, and 78% because of texture | Golden bread buns are well accepted by consumers when sold at a similar price as white flour bread buns |

| Sivaramane et al. (2008)45 | India |

|

Sensory attributes study (9-point hedonic scale, nominal [0, 1] scale) for sweetness, color, texture, aroma, general appearance of 80 g of cofermented boiled OFSP puree (16%) and cow’s milk with curd culture | Mean scores on sensory attributes on average were all > 7; consumers who find the curd acceptable had higher scores on color and texture than nonaccepters | Texture and color significantly and positively influenced consumer acceptability |

| Chowdhury et al. (2011)43 | Uganda |

|

Sensory attribute study (9-point hedonic scale) for taste, appearance, and overall acceptability of 4 varieties of cooked SP: white SP, orange SP, deep orange SP, and yellow SP | 52% of the participants preferred the deep orange SP, 26% the yellow SP, 13% the orange SP, and 9% the white SP | Deep orange SP is preferred over yellow, orange, and white SP |

| Rangel et al. (2011)21 | Brazil |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point facial hedonic scale mixed scale) for liking and numeric scale (1–10) for grading and preference of 50 g of cake (conventional vs 40% SP flour) | Overall acceptability was good and scale ranking was high for both cakes. No difference in preference found | Cakes with SP flour are acceptable and are an important strategy to provide provitamin A |

| Romero et al. (2011)13 | Nicaragua |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point facial hedonic scale) of 43 g of cake made with OFSP (24%), with and without leaf pulp (4%) | Acceptability was good with no difference between cakes, preference was similar between cakes | Both cakes were well liked. Inclusion of SP in preparation of the cakes is feasible |

| Tomlins et al. (2012)35 | Uganda |

|

Sensory attributes study (100-mm unstructured scale) for color, taste, flavor, texture, odor, and appearance of 11 varieties of cooked SP (white, yellow, purple, orange) | Color was correlated with carotenoid concentration in a logarithmic way. Carotenoid content correlated with dry matter and visual, odor, and textural characteristics. Cultivars differed widely regarding sensory characteristics | The logarithmic relationship between color and carotenoid concentration might result in orange varieties that are not necessarily high in carotenoids being preferred |

| Laurie et al. (2012)14 | South Africa |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point facial hedonic scale with facial expressions) for taste and yes/no for color, will to purchase and will to prepare OFSP juice, chips, doughnuts, and cooked leaves | Taste was liked best for doughnuts, followed by chips, leaves, and juice. The attributes color and willingness to buy and prepare the product scored high by > 80% of participants | All products were acceptable; preparation with deep frying was especially highly liked |

| Nguyen-Orca et al. (2014)27 | Philippines |

|

Sensory attributes study (7-point hedonic scale) for color, consistency, aroma, flavor, mouth feel, and general acceptability of a complementary food blend from 4 varieties of SP (cream, yellow, orange, and purple) with maize (55:45 ratio) | Orange SP was rated highest for color; both yellow and orange were rated highest for mouth feel, whereas consistency, aroma, and taste did not differ between samples. Overall, yellow (score: 5.6) and orange (score: 5.4) SP were liked over cream (score: 5.1) and purple SP (score: 4.5) | Yellow and orange SP blends, both high in provitamin A, were well accepted |

| Laurie et al. (2013)15 | South Africa |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point facial hedonic scale) for acceptability of color, acceptability of overall eating quality, as well as laboratory nutrient analysis, color and texture outcome for 9 orange-fleshed and 3 cream-fleshed cooked SP varieties | Most accepted varieties were associated with sweet flavor, dry mass, and maltose content, and least accepted varieties with wateriness. Acceptability correlated with maltose content, dry mass, and sweet flavor | Varieties with more dry mass are more acceptable |

| Fetuga et al. (2014)28 | Nigeria |

|

Sensory attribute study (9-point hedonic scale) for overall acceptability of amala prepared from 3 SP varieties (2 yellow and 1 orange) with different pretreatment (parboiling/soaking) and drying methods | Amala prepared from yellow varieties were scored high (7.3–7.7) whereas orange variety scored low (3.3–3.8). Parboiling scored higher compared with soaking. Acceptability significantly (negatively) correlated with ash, fiber, yellowness, water solubility, sugars, and viscosity peak time | Yellow SP was most acceptable for preparation of amala, suggesting that variety was a key factor |

| Olapade et al. (2014)46 | Nigeria |

|

Sensory attributes study (9-point hedonic scale) for acceptability of appearance, taste, mouth feel, and overall acceptability of crunchy snacks made of flour of cream SP and yellow SP with 0%, 30%, and 50% maize flour | Addition of maize flour enhanced acceptance of both SP varieties. 70% cream SP scored highest together with 50% yellow SP. 100% SP was scored lowest for both SP | A mix of yellow SP with maize flour results in a more acceptable snack than a mix of cream SP with maize flour |

| Trejo-González et al. (2014)44 | Mexico |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point hedonic scale) for crumb, crust color, firmness, and porosity; paired preference test with wheat bread; flour was replaced by various proportions of violet and orange SP flour (0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%) | All sensory attributes (except crust color) were significantly different between control breads and bread with 15%–20% SP flour | Substitution of wheat flour with 5%–10% SP flour yielded acceptable dough and bread |

| Tomlins et al. (personal communication, 2016) | Uganda |

|

Sensory attributes study (7-point hedonic modified scale) for appearance, odor, taste, and texture of cooked white, yellow, and orange SP | Overall acceptance was good: 100% acceptance of orange variety and 71% preferred orange over white. Nutrition information was significant predictor of acceptance; repetition of nutrition information or repeated exposure was not | OFSP is acceptable for children. Providing nutrition information increases acceptance |

| Tomlins et al. (personal communication, 2016) | Uganda |

|

Sensory attributes study (9-point hedonic scale) for sensory attributes of appearance, odor, taste, and texture of 30–50 g of 4 different cooked varieties of SP (white to orange) | Overall acceptance was good with mean scores > 6. The deep orange variety was acceptable to 82% and liked the most, followed by yellow, orange, and white. 18% of participants found orange SP unacceptable | The visible trait of orange SP can be used to advertise, but for the 18% dislikers other interventions are needed |

| Maize | |||||

| Stevens and Winter-Nelson (2008)49 | Mozambique |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point hedonic scale) for taste, appearance, texture, and aroma, and overall score of porridge (nsima) from milled orange and white near-isogenic lines of maize and local maize | Most participants preferred taste, texture, and appearance of local white maize nsima compared with other varieties. 33% rated taste of orange maize nsima as very good compared with 55% of local white maize Orange scored higher on appearance, and aroma of orange was preferred over white varieties | Color is not a particular factor for acceptance |

| De Groote et al. (2010)50 | Ghana |

|

Sensory attribute study (5-point hedonic scale) for appearance, aroma, texture, taste, and overall appreciation of kenkey (steamed fermented maize dough) from white, yellow, and orange maize varieties | Average scores were all > 3. In the Ashanti Region, white maize received the highest score (followed by yellow and orange), whereas yellow maize (followed by orange and white) received the highest score in Central and Eastern Regions | Preference for maize color was regional and is not regarded as an obstacle in the major maize areas of Ghana |

| Pillay et al. (2011)16 | South Africa |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point facial hedonic scale) for texture, aroma, and flavor; and paired preference test with 3 types of porridge made from yellow maize and white maize | Preschool children, secondary school children, and adults preferred yellow maize, but primary school children were indifferent. Acceptability was most influenced by texture and flavor | Yellow maize has potential but only when combined with nutrition education, reduced market price, more availability, and improved sensory properties |

| Khumalo et al. (2011)51 | South Africa |

|

Sensory attributes study (4-point facial hedonic scale) for aroma, color, consistency, hand feel, grittiness (mouth), and taste with maize porridge prepared from white sifted fortified and unfortified maize meal, hammer mill white and yellow maize meal with or without fiber, and white super maize meal | Scores for any of the sensory attributes did not differ between white and yellow maize with or without fiber, but maize without fiber (dehulled) was preferred. Overall, the whiter and finer the product, the more it was liked | Fine yellow maize was well accepted, although the super refined white maize was most preferred |

| Govender et al. (2014)52 | South Africa |

|

Sensory attribute study (5-point facial hedonic scale) for taste, texture, aroma, color, and overall acceptability of soft porridge made from white maize and 2 yellow provitamin A–biofortified varieties (medium and deep orange) | No significant difference between scores for the different sensory attributes. Outcome was not influenced by age | No difference in sensory acceptability of the white maize and provitamin A–biofortified maize |

| Awobusuyi et al. (2015)53 | South Africa |

|

Sensory attribute study (9-point hedonic rating scale) for aroma, mouth feel, taste, color, and overall acceptability of amahewu, a fermented nonalcoholic maize-based beverage made from white maize or provitamin A–biofortified maize | No significant differences in mean scores between amahewu prepared from white or provitamin A maize for color, taste, and aroma. Overall acceptability was significantly higher for provitamin A maize | Acceptability of amahewu prepared from provitamin A– biofortified maize is slightly higher than that prepared from white maize |

| Alamu et al. (2015)34 | Nigeria |

|

Sensory attributes study (9-point hedonic rating scale) for color, aroma, chewiness, taste, and appearance for boiled fresh orange maize of 2 hybrids with or without husk at 3 different maturation stages or 20, 27, and 34 d after pollination | Overall the hybrids were liked with average scores of 6.8. There was little difference between maize with or without husk, but optimum harvest time was 20 d after pollination | Orange maize hybrids are acceptable for fresh consumption |

| Beans | |||||

| Leyva-Martínez et al. (2010)47 | Cuba |

|

Sensory attributes study (4-point facial hedonic scale) for consistency, taste, and texture and triangle discrimination test and preference test for bean soup made with regular bean and biofortified (iron) beans | 63% of participants were able to discriminate the biofortified beans from regular beans. Overall acceptability was good for both varieties; no preference was found | The population liked the improved variety. It has the potential to be grown and consumed and to prevent iron deficiency |

| Tofiño et al. (2011)18 | Colombia |

|

Agronomic acceptance and sensory attributes study (children: 4-point hedonic facial scale; adults: 5-point hedonic scale) for consistency of the soup, color, taste, smell, and texture; and discriminatory testing of cooked biofortified (iron) beans and control beans | Agronomic performance of biofortified varieties is better. Overall acceptability in children and adults was good. In adults, biofortified bean scored higher. 88% of participants preferred biofortified beans. 68% of participants were able to differentiate | Biofortified bean SMN8 is well liked and has the potential to become the preferred type of bean for consumption and growing |

| Centeno et al. (2011)48 | Nicaragua |

|

Sensory attributes study (4-point facial hedonic scale) for sensory attributes of texture, smell, taste, and color and general acceptance of 3 biofortified beans and 1 control bean | Overall acceptability of beans was good. No preference was found, but control bean scored highest | Because the acceptability was similar for the beans, the improved varieties should be introduced to farmers to understand adoption |

| Cabal et al. (2014)17 | Colombia |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point hedonic scale) for acceptability of appearance, color, aroma, flavor, softness, resistance, hydration ability, and perception of granules of cookies made of 100% wheat (control); 15% biofortified bean, 15% cassava, 70% wheat; and 20% biofortified bean, 15% cassava, 65% wheat | Both biofortified cookies scored higher in aroma, flavor, resistance, hydration ability, and perception of granules than the control cookie | Biofortified bean flour can be used as a substitute for wheat flour to a certain percentage without losing sensory acceptance |

| Oparinde et al. (2015)41 | Rwanda |

|

Sensory attributes study (7-point hedonic scale) for color, bean size, taste, cooking time, storage quality, and ease of breaking after 7 days of home-use of RIB, WIB, and a local variety (Mutiki) | Overall, RIB were more liked (6.4–6.7) than the local variety (6.0–6.2) and the WIB (5.1–5.4), except for cooking time, for which WIB scored better. Scores for RIB were higher compared with control, whereas for WIB this difference was absent | RIB were superior over the local variety and WIB in sensory evaluation, even without information |

| Pérez et al. (2015)42 | Guatemala |

|

Sensory attributes study (7-point hedonic scale) for size, taste, cooking time, cooked thickness, and toughness after home testing with nutrition information and 3 times repeated nutrition information of control and biofortified beans | Sensory attributes were scored positive except for bean toughness. Nutrition information resulted in a higher score for the iron bean for raw bean size and cooked bean toughness, but repeating did not matter | The high-iron bean variety is liked in a similar way to the traditional bean |

| Carrillo-Centeno and Sánchez-Ruiz (2014)40 | Nicaragua |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point hedonic facial scale) for color, aroma, flavor, and texture, and preference test of 20 g of raw and cooked beans (INTA Ferroso [iron] and INTA Norte [regular]) | No difference in acceptability between the 2 varieties. Regular bean was preferred for color, iron bean for shape and size | Because acceptability was good, the iron bean should be introduced and promoted for growing and consumption |

| Murekezi et al. (personal communication, 2016) | Rwanda |

|

Sensory attributes study (7-point hedonic scale) for attributes of 4 different types of cooked biofortified beans; multinomial probit and logit models with 4 different types of sharing nutritional information and a control group with no information sharing | Overall sensory scores of all beans were good. Various consumer segments exist. In 2 sites, providing nutrition information increased the probability of shifting consumers to the iron-bean-likers segment | The results can be used for targeting interventions in various parts of and consumer segments in Rwanda |

| Oparinde et al. (personal communication, 2016) | Rwanda |

|

Sensory attributes (7-point hedonic scale) for raw bean color, raw bean size, cooked bean size, taste, cooking time, and overall acceptability of raw and cooked beans of control and 2 biofortified (IB1 and IB2) beans and as intervention various types of nutrition information and endorsement | Overall acceptability was good (score > 4) in both rural and urban sites. Between the 2 biofortified varieties, raw bean size and cooked bean size scored differently. IB2 was liked more, with no difference regarding endorsement or length of nutritional information. Cooking time of the local variety was liked most | Biofortified beans were acceptable, and a program to promote these beans can use a short version of nutritional information |

| Rice | |||||

| De Bree (2009)38 | China |

|

Triangle discrimination and preference test of uncooked grains of zinc-biofortified rice, zinc-fortified extruded rice, and normal rice. Focus group discussions | Participants were able to perceive a difference between the 3 rice types (P < 0.01). The odd sample was correctly chosen in 84% of control vs biofortified, 92% of biofortified vs extruded fortified, and 55% of control vs extruded fortified. Control and zinc-fortified rice were preferred over zinc-biofortified rice | Biofortified rice was the least preferred. Acceptance can be increased when rice kernels are large and whole, the government endorses the rice, and it can be locally grown |

| Montecinos et al. (2011)54 | Nicaragua |

|

Sensory attribute study (4-point hedonic scale) for texture, smell, taste, color, and overall acceptability of cooked Azucena, a traditional landrace rice with elevated iron and zinc levels compared with a local rice variety | The scores for the local variety were slightly higher than for Azucena (P < 0.05) for texture, smell, taste, and color. 56% of consumers preferred the local variety over Azucena | Azucena was not readily accepted by the study population |

| Vergara et al. (2011)39 | Panama |

|

Discrimination test with 30 g of cooked control and iron-biofortified rice | Only 30 of the 90 answers were correct, and therefore no significant difference between the 2 types of rice was found | Biofortified rice has potential and should be introduced in other communities and the agro-industry |

| Padrón et al. (2011)26 | Cuba |

|

Sensory attributes study (4-point facial hedonic scale) for color, texture, taste, and smell and preference test with 20 g of cooked iron-biofortified rice and control rice | > 80% of the respondents liked or really liked the biofortified rice. The biofortified rice was preferred (73%) over control | The biofortified rice variety should be introduced in Cuba because it can possibly help in the prevention of anemia and zinc deficiency |

| Cassava | |||||

| Talsma et al. (2013)20 | Kenya |

|

Preference test and blinded triangle discrimination test with boiled and mashed yellow and white cassava | Caretakers and children were able to discriminate between yellow and white cassava; > 70% preferred yellow cassava. Characteristics of yellow cassava: attractive color, soft texture, sweet taste | Yellow cassava is acceptable to schoolchildren and their caretakers |

| Njoku et al. (2014)56 | Nigeria |

|

Sensory attributes study (4-point hedonic scale) for color, taste, texture, mealiness, and appearance of eba made of gari from 3 yellow cassava varieties and 1 white cassava variety mixed with palm oil | Yellow cassava was preferred over white because of the color, premium price, nutritional value, and texture | Yellow cassava can be adopted by farmers if made available |

| Awoyale et al. (2015)36 | Nigeria |

|

Sensory attributes study (9-point hedonic scale) for acceptability of mouth feel, taste, color, flavor, appearance, and of a gruel made of different mixtures of yellow cassava starch–based custard powder (90%–98%) with egg powder (2%–10%) measured at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 wk of storage | Blend ratios and storage conditions affected the acceptance. At 24 wk, color and taste were disliked, which might be because of increase in moisture during storage | Yellow cassava custard can be stored for 24 wk and still be acceptable |

| Oparinde et al. (2014)55 | Nigeria |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point hedonic scale) for color, feel, taste, and drinking quality of gari and color and feeling for eba made from white, light yellow, and deep yellow cassava, with and without prior information | Mean scores were > 3 and different across product types. In Imo State, white cassava scored highest, followed by deep yellow and light yellow. In Oyo State, light yellow cassava rated highest, whereas deep yellow was rated highest in color and feel. There is no effect of information on liking | Consumers rated the light yellow and deep yellow cassava differentially on all sensory attributes. Study area was important factor for preference, but the deep yellow was never preferred |

| Pearl millet | |||||

| Birol et al. (2015)57 | India |

|

Sensory attributes study (5-point hedonic scale) for grain color/size, and color, taste, layers, and ease of breaking of bhakri (thick flatbread) made of HIPM or LPM | Overall, HIPM was rated higher (4.2–4.9) for all attributes compared with LPM (3.5–4.2). Information (groups B and C) increased the scores for HIPM and decreased scores for LPM, except for grain color, which remained the same | Consumers evaluate HIPM more favorably than LPM varieties |

Abbreviations: F, female; HIPM, high-iron pearl millet; IB1, iron bean 1; IB2, iron bean 2;; LPM, local pearl millet; M, male; OFSP, orange-fleshed sweet potato; PFSP, purple-fleshed sweet potato; RIB, iron biofortified red bean; SP, sweet potato; WIB, iron biofortified white bean.

Sweet potato

Consumers of traditional products

In eastern and southern Africa, sweet potato is traditionally prepared by boiling and is served as a side dish. Cooked varieties of sweet potato were evaluated for their sensory properties in Uganda (Tomlins et al., HarvestPlus, personal communication, 2016),35,43 Tanzania,19 and South Africa.15 In Uganda, deep orange sweet potato (containing the highest provitamin A content) was preferred over yellow, orange, and white sweet potato by 52% of rural and urban consumers (n = 467).43 In a small study, it was found that the sensory characteristics of white, yellow, purple, and orange sweet potato varied widely between cultivars.35 Among primary school children (n = 120), 71% preferred orange over white sweet potato (Tomlins et al., HarvestPlus, personal communication, 2016), and 82% of adult rural and urban household members (n = 475) evaluated the deep orange variety as being equally acceptable as white sweet potato (Tomlins et al., HarvestPlus, personal communication, 2016). In Tanzania, mothers liked orange sweet potato better than a purple variety, whereas school children liked both varieties similarly.19 In South Africa, acceptance was more related to sweet flavor, dry mass, and maltose content (as analyzed in the laboratory) than to color; wateriness was associated with the least accepted varieties.15 From these studies it can be concluded that orange sweet potato, prepared in its traditional way by boiling, is well accepted from a sensory standpoint by both adults and children in the countries where the studies were conducted.

In Western Africa, tubers and roots are often processed into flour that is then used to prepare food products for consumption. In Nigeria, flour from yellow and orange sweet potato varieties was evaluated for use in the preparation of a local porridge called amala. The yellow variety (with lower provitamin A concentration) was more acceptable than orange varieties (with higher provitamin A concentration) by university students (n = 100). Sensory acceptability was correlated with ash, yellowness, water solubility, fiber, sugar, and viscosity peak time.28

Consumers of nontraditional products.

In 8 studies, OFSP was experimentally included in nontraditional products and evaluated for sensory properties. Low et al.37 found that bread buns in which 38% of wheat flour was replaced by boiled and mashed OFSP (“golden bread”) were preferred over white flour bread buns. The buns were sold at 2 local markets in Mozambique irregularly for 2 years. During a 2-day study at these markets with 112 untrained market shoppers, 47% bought the golden bread buns, which were priced the same as the white flour buns. Bread with 5%–10% orange sweet potato flour was also evaluated as satisfactory in Mexico.44 In India, rural consumers positively evaluated the sensory properties of curd prepared from cow’s milk and 16% cofermented boiled orange sweet potato puree.45 School children in Nicaragua13 and Brazil21 found cake prepared with 24%–40% OFSP flour to be equally as acceptable as conventional cake. An instant complementary food blend (sweet potato/maize: 55:45 ratio) was evaluated by university students (n = 50) in the Philippines; blends that included orange or yellow sweet potato flour were ranked highest for color and mouth feel and were liked over blends that included cream and purple sweet potato.27 In Nigeria, crunchy snacks made of yellow sweet potato and maize flour (50:50 ratio) were well accepted for consumption, whereas snacks made of 100% sweet potato flour (either cream or yellow) were least accepted by consumers.46 From a sensory perspective, nontraditional food products (novel recipes) prepared with orange sweet potato varieties were generally liked.

Producers and consumers of nontraditional products.

Laurie et al.14 evaluated the sensory acceptability of various OFSP products among local farmer groups and schoolchildren (n = 950) in South Africa. Of the products tested, doughnuts were most liked, followed by chips, cooked leaves, and juice.

Beans

Consumers.

Among households in northwest Guatemala (n = 360), iron-biofortified beans were equally acceptable as control beans after a period of home testing.42 Among Colombian adults and children (n = 273), 88% preferred iron-biofortified beans to accompany a rice meal compared with control beans.18 Also in Colombia, iron-biofortified bean flour (15% and 20%) was used to replace wheat flour in the preparation of cookies, and these cookies were evaluated with higher scores overall by school children.17 In Rwanda, iron-biofortified red beans were liked better than either the local variety of beans or iron-biofortified white beans after 7 days of home testing of the beans (n = 572).41 In a later study, the same investigators found that the acceptability of iron-biofortified beans was again good and did not differ between urban and rural populations or in relation to the levels of nutrition information provided (Oparinde et al., HarvestPlus, personal communication, 2016).

Producers and consumers.

Iron-biofortified beans prepared as soup were well accepted by bean producers and consumers (n = 80) in Cuba, and there was no difference in the acceptability of the iron-biofortified beans compared with the regular beans.47 In Nicaragua, 2 studies conducted among bean farmers and consumers showed a similar acceptance of cooked iron-biofortified beans and control beans.40,48 Murekezi et al. (personal communication, 2016) also found that the sensory properties of iron-biofortified beans were acceptable in both the rural and urban areas of Rwanda (n = 1809). Furthermore, they found that provision of nutrition information increased the probability that consumers would shift to liking iron-biofortifed beans and that more consumers who liked iron-biofortified beans were found in urban markets and among farmers.

Summary finding.

It can be concluded that the sensory properties of iron-biofortified beans are well accepted among both consumers and producers in the populations studied thus far.

Maize

Consumers.

For the studies of maize included in this review, only traditional preparation methods were evaluated. White maize refers to non-biofortified maize and yellow or orange maize refers to maize biofortified with provitamin A. Market shoppers (n = 201) in Mozambique preferred the taste and texture of white maize, whereas the aroma of orange maize was preferred.49 In Ghana, sensory acceptance of kenkey (steamed fermented maize dough) prepared from white, yellow, and orange maize varieties was compared among household heads or their spouses (n = 703). White maize was preferred the most and orange maize the least in the Ashanti Region, whereas yellow maize was most preferred in the Central and Eastern Regions.50 In South Africa, maize porridge from fine yellow maize was well accepted, although women preferred porridge from white maize without fiber.51 In another study, yellow maize porridge was preferred over white maize porridge by preschool children, secondary school children, and adults, whereas primary school children were indifferent (n = 212).16 In a study with caregivers of infants (n = 60), the caregivers indicated no difference in sensory attributes between orange or white maize porridge.52 Also, no significant difference was found in the sensory perception of amahewu (fermented nonalcoholic beverage) prepared from white maize compared with that prepared from provitamin A–biofortified maize in a rural community (n = 54).53 Overall, acceptance of 8 freshly boiled orange maize varieties was scored as 6.8 on a 9-point scale by a trained panel (n = 10) in Nigeria, but no comparison with a control maize was done.34 In summary, yellow and orange maize is accepted from a sensory perspective, although there is some regional variation.

Producers and consumers.

No studies that assessed producers’ preferences for biofortified maize were identified.

Rice

Consumers.

Rice biofortified with zinc was preferred less than normal rice and rice externally fortified with zinc by rural women (n = 40) in China.38 Government endorsement of the rice and the possibility to cultivate the rice locally would likely enhance acceptance. 38 When comparing a traditional landrace rice with high iron and zinc concentration (Azucena) with a local rice variety, 56% of consumers in Nicaragua (n = 203) preferred the local variety.54 Rice consumers (n = 90) in a poor area of Panama were not able to distinguish iron-biofortified rice from control rice.39 Iron-biofortified rice was well accepted by pregnant women (n = 98) in Cuba, with 73% of the study population preferring the biofortified rice over the control rice.26 Results from these 4 studies are divergent, and sensory properties of biofortified rice should be further investigated.

Producers and consumers.

No studies that assessed producers’ preferences for biofortified rice were identified.

Cassava

Consumers.

School children (n = 30) and their caretakers in Kenya (n = 30) were able to discriminate between yellow (provitamin A biofortified) and white (non-biofortified) cassava when tasting cooked and mashed cassava while blindfolded. More than 70% of the respondents preferred the yellow cassava.20 A study conducted in Nigeria (n = 671) with 2 products that used cassava gari (roasted fermented cassava flour) and eba (dough ball prepared from fermented cassava flour) made from white (non-biofortified), light yellow (provitamin A biofortified), and deep yellow (provitamin A biofortified) cassava showed that liking of the light yellow cassava varied by location and that deep yellow varieties were not preferred.55 Custard powder from yellow (provitamin A biofortified) cassava starch lost its acceptability after 24 weeks of storage, as evaluated by a Nigerian panel trained to recognize and differentiate food sensory properties (n = 12).36

Producers and consumers.

A study in Nigeria among cassava farmers (n = 30) residing in southeastern Nigeria showed that yellow cassava eba was preferred over white cassava eba because of color, premium price, nutritional value, and texture.56

Summary finding.

In summary, although yellow cassava seems to be acceptable from a sensory perspective, the number of studies is limited.

Pearl millet

Consumers.

Flatbread (bhakri) prepared from high iron–biofortified pearl millet was rated with higher scores than that prepared from local varieties of pearl millet by Indian consumers (n = 452).57 However, only this 1 study on the sensory acceptance of biofortified pearl millet was found.

Producers and consumers.

No studies that assessed producers’ preferences for biofortified pearl millet were identified.

Sociocultural drivers and determinants of acceptance and adoption

Twenty-one studies on the sociocultural drivers and determinants of consumer adoption of biofortified crops were found (Table 420,22–25,51,52,58–60,61–69,70,71). The crop most studied in this respect was sweet potato (n = 9), followed by maize (n = 5), cassava (n = 4), rice (n = 2), and beans (n = 1). Sweet potato, maize, and beans were only studied in Africa, cassava was studied in both Africa (Benin, Kenya) and Latin America (Brazil), and rice was only studied in a single Asian country (China). Four studies included genetically engineered crops.58–60,71 Data were mostly collected by surveys and structured questionnaires (n = 14),20,28,58–68,71 sometimes in combination with focus group discussions (n = 3).51,52,64 In a few cases, the data were generated by an intervention study (n = 4)22–24,69 or a clinical trial (n = 1).25

Table 4.

Sociocultural drivers and determinants of acceptance and adoption for consumers of biofortified crops in low- and middle-income countries

| Reference | Country | Study Population | Method and Study Design | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet potato | |||||

| Mazuze (2004)61 | Mozambique |

|

Cross-sectional study. Structured questionnaire (about growing and adoption of OFSP) |

|

OFSP adoption can be improved by providing credit for animal traction, improving drainage systems, and providing access to more drought-tolerant vines. More research into postharvest processing and storage of roots would help to reduce the low availability of roots due to seasonal planting |

| Low et al. (2007)24 | Mozambique |

|

|

Production expanded from 33 to 359 m2; participation in OFSP production and sales increased in intervention households but decreased in control households; 90% of intervention households grew OFSP compared with 11% in control; SP production increased from 73 kg to 127 kg (71% OFSP); Percentage households selling increased from 13% to 30%, but no increase for households; > 50% of children in intervention consumed OFSP at least 3 out of 7 d as compared with 4%–8% of control children | Integrated promotion of OFSP has potential to increase adoption of OFSP and increase consumption |

| Hotz et al. (2012)22 | Mozambique |

|

Randomized controlled effectiveness trial (2.5 y) with 3 arms: control, OFSP distribution plus 1 y or 2 y intensive training | 77% adoption; share of OFSP cultivated area increased from 9% to 56%; OFSP intake significantly increased in intervention groups for 6–35 mo (46 g/d), 3–5.5 y (48 g/d), and women (97 g/d) compared with control; no difference in effect between the 2 intervention groups | OFSP is well adopted and consumed after introduction; group-level trainings in nutrition and agriculture could be limited to the first year of project without compromising impact |

| Hotz et al. (2012)23 | Uganda |

|

Randomized controlled effectiveness trial (2 y) with 3 arms: control, OFSP distribution plus 1 y or 2 y intensive training | OFSP intake increased in both intervention groups (P < 0.01), accounting for 44%–60% of vitamin A intake at follow up. Prevalence of inadequate vitamin A intake was reduced among children 6–35 mo (> 30 percentage points) and women (> 25 percentage points), with no difference between intervention groups | SP was adopted and grown by farmers resulting in incorporation of OFSP into the diets of women and children with a measurable impact on vitamin A status in children |

| Fetuga et al. (2013)62 | Nigeria |

|

Cross-sectional study. Structured questionnaire (OFSP processing, OFSP amala (stiff porridge) consumption, OFSP awareness) |

|

|

| Gilligan et al. (2014)63 | Uganda |

|

Household survey on adoption rate and comparison of intrahousehold bargaining power based on asset ownership and control over land use | Adoption rate in season 1 was high (90%) but declined to 69% in season 4, varying per district, due to vines drying up, no access to new planting material, insufficient availability of labor available, and dislike of crop. Among female-headed households (11%), exclusive control over land was positively associated with OFSP adoption. This association was absent among male-headed households. OFSP adoption was associated with age of the head of household, knowledge of vitamin A, and total land area cultivated with sweet potato. Women with a high share of nonland assets ownership were less likely to grow OFSP | OFSP was well adopted in this region of Uganda. Female bargaining power does not unambiguously increase the probability that a household adopted OFSP in response to the project. The probability of adopting OFSP was lowest on parcels exclusively owned by men and largest on parcels jointly owned by males and females with women in the lead. Engaging with both men and women might be the best strategy to promote adoption |

| De Brauw et al. (2015)69 | Mozambique |

|

Randomized controlled effectiveness trial (2.5 y) with 3 arms: control, OFSP distribution plus 1 y or 2 y intensive training | Children in households with more participation had higher dietary vitamin A density, and slightly higher mean micronutrient density and dietary diversity | Intensity of participation in extension activities is associated with larger project impact |

| Yanggen and Nagujja (2006)64 | Uganda |

|

Cross-sectional survey with questionnaires, key-informant interviews and focus group discussions (women only, men only, and mixed groups) | 64% of farmers adopted OFSP in intervention compared with 22% in nonintervention areas. Main OFSP production constraints were pests and diseases (especially weevils), drought, and availability of vines (no commercial vine distribution), followed by lack of capital and labor. Major favorable characteristics farmers look for are yield, sweet taste, early maturity, and drought resistance, followed by consumer characteristics like tuber quality, good price, high dry matter, color, good storability, low fiber, and nutritional content. Nutrition content comes last as favorable characteristic, only mentioned by women (as 4th most important) but not by men. Most important information sources were nongovernmental organizations, fellow farmers, and agricultural extension workers | Nutrition concerns cannot be depended upon to push the adoption of OFSP. OFSP must be competitive with white and yellow varieties in terms of agronomic, consumer, and economic characteristics (in terms of yields, taste, price, etc) if it is to be successful. Nutrition education campaigns must be an integral part of the promotion of OFSP |

| Machira et al. (2013)70 | Kenya |

|

Interviews and focus group discussion with key persons about an integrated nutrition, agriculture, and health intervention that delivers OFSP through antenatal care services in western Kenya | Food security and health benefits were most recognized by participants. Mothers indicated that their children were less susceptible to disease and were more energetic; shorter maturation and higher yield of OFSP were also valued. Health workers perceived higher antenatal care attendance and increased healthcare-seeking behavior as benefits. Challenges were distance to health facility, misperceptions (OFSP = contraceptive), need for continuous community sensitization, and increased workload with remuneration for community volunteers and vine multipliers | Perceived benefits and motivating factors outweighed challenges of integrating OFSP with antenatal care service |

| Maize | |||||

| Tschirley and Santos (1995)65 | Mozambique |

|

Cross-sectional study | 22% of households consumed predominantly yellow maize. Consumers of yellow maize had substantially lower income than white maize consumers. Highest income consumers were the least likely to consume yellow maize | Yellow maize is well accepted, especially among poor consumers |

| Muzhingi et al. (2008)66 | Zimbabwe |

|

Cross-sectional study (in-depth questionnaires, focus groups discussion) | Yellow maize was known by most respondents but mainly from food aid. Link with food aid and bad taste (due to organoleptic changes during storage) were seen as negative aspects of yellow maize. Nutrition information on vitamin A and taste were significant contributors to acceptance | Acceptance could be improved if nutrition knowledge was increased |

| Khumalo et al. (2011)51 | South Africa |

|

Focus group discussions (consumer attitudes, perceptions, and practices) of maize porridge prepared from several types of white and yellow maize meal | Preference for yellow maize related to knowledge of the presence of vitamin A in yellow maize meal (acquired during previous training in 2004), availability (during drought as relief food), and price determined whether yellow maize is bought | Acceptability of yellow maize mainly related to nutritional reasons. Availability was the largest obstacle |

| Govender et al. (2014)52 | South Africa |

|

Focus group discussions (acceptability of provitamin A–biofortified maize for preparing maize porridge for their infants) | Yellow maize is not sold in supermarkets, suggesting that white maize is of better quality. Yellow maize considered to be for poor people or animals. Affordability, availability, and health benefit were reasons for being willing to give provitamin A–biofortified maize porridge to their infants | Affordability, availability, and health benefit were important determinants of accepting provitamin A–biofortified maize as infant food |

| Schmaelzle et al. (2014)25 | Zambia |

|

Randomized controlled feeding trial with 3 arms: porridge (nsima) of orange maize and placebo oil; of white maize and placebo oil; of white maize and vitamin A supplement | Orange group consumed less nsima (276 ± 36 g) than white groups (288 ± 26 g and 288 ± 25 g, P = 0.08), with consumption fluctuation between weeks, and no difference in total food intake and relish intake. Mothers and staff preferred orange maize because of softer structure and sweeter flavor than the white maize; because of texture it was difficult to use orange maize nsima to scoop up relishes | Implementation and adoption of new and biofortified foods is possible with promotion, especially in very traditional cultures that are deeply connected to their food |

| Cassava | |||||

| González et al. (2009)58 | Brazil |

|

Cross-sectional study on genetically engineered cassava. Structured questionnaire after explanation about genetically engineered yellow cassava | 25% of respondents had ever heard about genetic engineering, 22% found it a possible health risk. Age, trust in authorities, perceived health risk, and access to media influenced consumer support of genetically engineered crops | Attitudes toward genetically engineered biofortified yellow cassava is positive |

| González et al. (2011)59 | Brazil |

|

|

15% of farmers planted the yellow cassava 1 y after the release (early adoption rate), and 62% said they would do so next year (potential/intentional adoption rate), because of the better nutritional content. Reasons for not adopting were low availability of seeds and taste. From the farmers who received seeds, 63% planted them. Key factors were receiving information, involvement in previous participatory research, and knowledge about nutritional advantages | To increase early adoption of yellow cassava, it is important to increase the nutrition knowledge, have high availability of seeds, and use information and socialization among producers |

| Uwiringiyimana (2012)67 | Benin |

|

|

90% had intention to prepare yellow cassava for their children 2 or more times a week. Health behavior identity, knowledge, and perceived susceptibility predicted intention to consume yellow behavior, as well as cues to action | Intention can be increased by increasing knowledge on vitamin A deficiency and health benefits of yellow cassava and increasing positive triggers as recommendations from influential people and educational campaigns |

| Talsma et al. (2013)20 | Kenya |

|

|

Almost all had intention to prepare yellow cassava for their children, of which 64% were willing to do so 2 or more times per week. Knowledge about provitamin A–rich cassava and its relation to health was a strong predictor of health behavior identity. Worries related to bitter taste and color, belief about being in control to prepare cassava, and activities such as information sessions about provitamin A–rich cassava and recommendations from health workers predicted intention to consume provitamin A–rich cassava | The yellow color is no barrier for consumption. Intention to consume can be increased by reducing barriers (like worries about color, taste, texture, and bitterness); by increasing knowledge on vitamin A deficiency and provitamin A–rich cassava; by empowering mothers to decide what to cook; and by involving health workers in the promotion of yellow cassava |

| Rice | |||||

| De Steur et al. (2013)71 | China |

|

Cross-sectional study questionnaire (perceptions on genetically engineered folate-biofortified rice) | Taste and health are the most important attributes for rice purchase, followed by price and external appearance. Respondents answered correctly on 42% of the questions concerning knowledge of genetically engineered foods. 62% of respondents were in favor of genetically engineered folate biofortification of rice. A negative change in taste decreased this proportion to 28%, environmental impact decreased it to 29%, price decreased it to 35%, availability decreased it to 41%, external appearance decreased it to 46% and cultivation potential decreased it to 50% | Initial acceptance rate would be halved if genetically engineered folate-biofortified rice would have a negative effect on taste, price, or the environment. Multiple attributes should be taken into account in the development of biofortified crops |

| De Steur et al. (2015)60 | China |

|

Cross-sectional study. Questionnaire on genetically engineered rice, including false/true statements, 5-point hedonic scale statements, a knowledge score, 4 additional scores (benefits, risks, safety, price), overall trust scores for information channels or sources | 66.5% in favor of nutritionally enriched rice; 39% had limited knowledge about genetically engineered food; 3 groups of consumers: enthusiasts (14%: health, lower pesticide use, males, rural, farmer), cautious (41%; positive on safety, females, urban); and opponents (45%; side effects, including biodiversity, females, low income, rural). Enthusiastic respondents have a more positive attitude | There is a promising (segmented) market potential for second-generation genetically engineered products |

| Beans | |||||

| Asare-Marfo et al. (2016)68 | Rwanda |

|

Cross-sectional impact assessment study by listing exercise to identify HIB growers among bean-producing households with questionnaires | Over the last 5 y, of the 93% households that grew beans, 29% respondents indicated to have grown an HIB variety. Out of the 84% of farmers who indicated to have grown beans in the second season of 2015, 21% have grown at least 1 HIB variety. Within the country this varied by location, with Eastern Province having higher adoption rates. Adoption rate was further determined by yield, easiness to farm the variety, commercial value, and availability of seeds. The main source of first planting material were the markets (41%) and social networks (23%) | Adoption rates of HIB varieties in Rwanda are very promising |

Abbreviations: F, female; HIB, high-iron bean; M, male; OFSP, orange-fleshed sweet potato; SP, sweet potato.

Sweet potato

Producers and consumers.

Acceptance and adoption of sweet potato has been most extensively studied in Mozambique. A structured questionnaire given to farmers (n = 150) who had received OFSP vines in the year 2000 in Gaza Province, Mozambique, revealed that the adoption rate varied per season from 38% to 71%, although only a small proportion (14%–17%) of land was planted with OFSP 2 years after the vines were first provided. Adoption of the introduced OFSP variety was positively associated with participation in promotion activities, vine distribution, larger cultivated area, and less frequent flooding. The small proportion of land planted with OFSP was attributed to unavailability of vines, limited propagation capacity, and lower drought-tolerance of OFSP, whereas reasons for planting OFSP were yield, taste, and the desire to experiment with new varieties.61 A prospective controlled trial with a 2-year integrated promotion campaign for OFSP production and OFSP vine distribution led to increased adoption, consumption, production, and plot size of OFSP in intervention villages compared with control villages.24 A later effectiveness study comparing OFSP distribution with a 1-year or a 2-year intensive training program showed similar results and also revealed that intensive promotion activities could be limited to 1 year instead of 2 years.22,69

A very similar effectiveness study conducted in Uganda that compared OFSP distribution with a 1-year intensive training program and OFSP distribution with a 2-year intensive training program also showed that OFSP was well adopted and incorporated into the diets of women and children irrespective of the length of the training program.23 Earlier work in Uganda compared farmers from an intervention area in which OFSP was introduced with farmers from a control area where OFSP was not introduced. Among 160 selected farmers, the adoption rate was 64% in the intervention area compared with 22% in the control area, with yield, taste, and price being the most important drivers for adoption.64 Also in Uganda, another adoption study (n = 1176) revealed that adoption was high in season 1 (90%) but declined in each consecutive season to 69% in season 4. The researchers specifically addressed women’s bargaining power and found that female and joint (wife and husband) ownership of parcels for OFSP cultivation was the best strategy to promote adoption.63

A study conducted in 6 states in southwestern Nigeria revealed that only 48 (16%) of 300 respondents had heard of OFSP, with knowledge of OFSP unrelated to sex, age, or education level. Almost none of the respondents (1.7%) were aware of the health benefits of OFSP.62 In the same study, it was found that, of 23 respondents who were engaged in sweet potato processing, 15 used yellow-fleshed sweet potatoes, and 1 had once tried OFSP. Color, availability, and taste were mentioned as drivers of choice for the variety of sweet potato for processing.62

Summary finding.

In summary, it can be concluded that OFSP has been well accepted and adopted in countries where it has been actively spread and promoted, such as Mozambique and Uganda. Building on this, similar programs are currently underway in other African countries.72–74 An innovative project in western Kenya that delivers OFSP through antenatal care services proved to be beneficial for participants because the general health of the children as perceived by the children’s mothers increased and antenatal clinic attendance was higher.70

Maize

Consumers.

A survey of urban households in low-income neighborhoods in Maputo, Mozambique (n = 400) showed that 22% of households consumed predominantly yellow maize biofortified with carotenoids. This was associated with lower levels of household income within these neighborhoods.65 In Zimbabwe, a study of rural and urban households (n = 316) showed that yellow maize consumption was associated with food aid. The study also indicated that bad taste after storage impeded acceptance of yellow maize.66 Participants (n = 48) in a study conducted in Limpopo Province, South Africa, indicated the presence of vitamin A in yellow maize meal as the reason for their preference.51 This awareness was the result of a research project involving the promotion of vitamin A–rich foods that had coincidentally been conducted earlier in the same area. Unavailability of yellow maize was mentioned as the main obstacle for its consumption. Another study conducted in South Africa among female caregivers of infants (n = 21) showed that these caregivers considered yellow maize to be for poor people or animals. Price, availability, and health benefit were important determinants of acceptance.52 In a randomized controlled feeding trial in Zambia, biofortified orange maize was well accepted by children, caretakers, and trial staff because of the softer structure and sweeter flavor.25 In summary, biofortified yellow maize was liked by some groups and not by others, and biofortified orange maize was well accepted for human consumption in 1 study.

Producers and consumers.

No studies that assessed producers’ sociocultural drivers and determinants of adoption of biofortified maize were identified.

Cassava

Consumers.

A study of households of cassava buyers (n = 414) in northeastern Brazil that investigated acceptance of yellow cassava biofortified through genetic engineering showed a positive attitude toward acceptance.58 Consumer support was influenced by older age, trust in authorities, high perception of general personal health risk, and access to media. Studies in Benin and Kenya revealed that the color of yellow cassava was not a barrier to consumption. Also, caregivers’ knowledge of vitamin A deficiency and the health benefits of yellow cassava were important determinants of the intention to feed yellow cassava to children.20,67 These studies indicate that availability and information on the health benefits of yellow cassava are important determinants for its acceptance. However, this can only be explored further when yellow cassava becomes available on a larger scale.

Producers and consumers.

Another study in Brazil was conducted on the adoption rate of conventionally bred yellow cassava among cassava farmers who were either exposed to 1) participatory research (n = 760) or 2) a promotion event after which farmers requested seeds (n = 158). The early adoption rate (< 1 y) was 15% in the participatory research group, although 62% indicated they planned to plant the biofortified yellow cassava the next year because of the better nutritional content. In the group that received yellow cassava seeds, 63% planted them. Key factors for adoption were availability, taste, involvement in participatory research, and knowledge about nutritional advantages.59 This study also indicated that availability and information on the health benefits of yellow cassava are important determinants for its future acceptance, but this needs to be confirmed in further research once yellow cassava becomes available on a larger scale.

Rice

Consumers.

A structured interview on perceptions about folate-rich rice that was biofortified through genetic engineering was conducted among rice consumers (n = 588) encountered near supermarkets, shopping areas, and outdoor markets in Shanxi Province, China. Sixty-two percent of respondents viewed folate-rich rice favorably. Taste, environmental impact, price, availability, appearance, and cultivation potential were determinants of acceptance.71 In another study that included 451 rice consumers in the same area, 67% were willing to accept folate-rich genetically engineered rice, although knowledge of genetically engineered foods was low (39%) in the study population. Those strongly in favor of folate-rich genetically engineered rice (14%) mentioned health and lower pesticide use as reasons, whereas opponents of folate-rich genetically engineered rice (45%) were worried about environmental side effects.60

Producers and consumers.

No studies that assessed producers’ sociocultural drivers and determinants of adoption of biofortified rice were identified.

Bean s

Producers and consumers.

In 2015, an impact assessment study in Rwanda was conducted among 19 000 bean-producing and bean-consuming households to quantify the adoption rates of growing high-iron bean varieties in a country where high-iron beans had been promoted and released for several years.68 This study found that over the past 5 years, 29% of the farmers had been growing high-iron bean varieties. During the second growing season in 2015, 21% of the farmers who were growing beans were growing high-iron bean varieties. Adoption of the high-iron beans varied by location within the country and by variety, with yield, ease of farming the variety, availability of seeds, and commercial value of the beans among the most important determinants of adoption for a certain variety. Although this is the only study on adoption rates of beans, these results are promising and show that with a good support program high-iron beans can be well adopted.

Consumer adoption and marketability

Twenty-five studies on consumer adoption and marketability of biofortified crops were found (Table 529–32,37,41–43,49,50,55,57,58,65,75–82). The crop most studied in this respect was maize (n = 8), followed by rice (n = 6), beans (n = 4), sweet potato (n = 3), pearl millet (n = 2), and cassava (n = 2). The studies were conducted in Africa (n = 16), Asia (n = 8), and Latin America (n = 2). All studies on genetically engineered crops (rice) were conducted in South Asia and Southeast Asia (n = 6).

Table 5.

Predicted adoption of biofortified crops as evidenced by consumer willingness to pay in low- and middle-income countries

| Reference | Country | Study Population | Method and Study Design | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet potato | |||||

| Low and van Jaarsveld (2008)37 | Mozambique |

|

Calculation of costs and revenues of producing bread buns with 38% of wheat flour replaced by boiled and mashed OFSP (golden bread) | Calculated net return to labor was 3 times higher for golden bread buns vs white wheat flour buns due to lower costs | Small-scale golden bread production is an economically viable option for creating a market for OFSP |

| Naico and Lusk (2010)81 | Mozambique |

|

Choice experiment: 9 choice sets of the attributes pulp color (white/ orange), dry matter content (low/ medium/high), size (small/medium/large), and price (M7.5/10/15/kg) with treatment 1 and 2: visual exposure to a bag of sweet potato of each variety. One bag was given to each participant based on their preference from the choice questions. Treatment 3 and 4: no exposure | Price correlated negatively with preference. Dry matter was the most important attribute to the participants. Small-sized roots were more preferred in the rural area but not in the urban area. Consumers are willing to pay 51.3% more for OFSP relative to WFSP | Dry matter is a key factor driving consumer acceptance. When dry matter, price, and size are equal, orange pulp color is preferred over white pulp color |

| Chowdhury et al. (2011)43 | Uganda |

|

Valuation by choice experiment (17 scenarios) of 4 varieties of: 1 white sweet potato; 2 OFSP; and 1 yellow sweet potato, after (1) no nutritional info and asked to make real choices and commitments (n = 121); (2) nutritional info about OFSP and asked to make real choices and commitments (n = 115); (3) nutritional info and hypothetical assessments (n = 118); (4) nutrition information and “cheap talk” script and hypothetical assessments (n = 113) | In scenario (1) no difference in WTP for deep-orange vs white was found, whereas WTP for orange and yellow sweet potato was lower (−22% and −30%, respectively) compared with white. In (2) a premium was found for deep-orange variety relative to white (+25%). In (3) higher WTP for yellow (+40%), orange (+43%), and deep orange (+48%) vs white. In (4) higher WTP for yellow (+26%), orange (+26%), and deep orange (+52%) vs white. Respondents who preferred a variety in the sensory assessment were willing to pay more for that variety. Rural consumers had a higher WTP for OFSP varieties compared with urban consumers. | Consumers in Uganda are willing to pay similarly for biofortified (deep orange) varieties as for the traditional white variety, even without a promotional campaign. Provision of nutritional information translates into an increase in WTP for deep OFSP. Taste is an important attribute in WTP. Hypothetical scenarios translate into biased WTP; therefore, experiments with real transactions are superior |

| Maize | |||||

| Tschirley and Santos (1995)65 | Mozambique |

|

Price game assessing the percentage of respondents switching from white to yellow maize after a given discount rate | At a 14% discount, 25% of consumers would switch from white grain to yellow grain, whereas at a discount of 43%, 70% of consumers would switch. Lower-income consumers are more likely to switch at modest price discounts. At higher discount (> 43%), higher-income consumers are just as likely to switch to yellow maize | Reduced price is an important determinant of consuming yellow maize |

| Rubey and Lupi (1997)77 | Zimbabwe |

|

Focus group discussions and preference ranking (refinedness, product price, color, travel time for obtaining meal, product packaging) | The predicted share of households consuming yellow maize was 25% when sold at a 10% discount compared with white maize | Yellow maize is well accepted, provided that it is sold at a lower price than white maize and widely available |

| Stevens and Winter-Nelson (2008)49 | Mozambique |

|

Trading experiments based on acceptance to trade white maize for orange maize at different prices and willingness to trade white maize with tomatoes, orange, and white near-isogenic lines of maize | Acceptance rate of orange maize meal at all trade ratios was 44%; factors reducing acceptance for trade are being male, being a nonshopper, being a bad taste judger, finding local maize tastes better than orange maize, and frequently eating meat/fish. Household size, the presence of small children, dietary diversity, and perceived taste were determinants of trade acceptance | Existing preferences for white maize do not preclude acceptance of orange biofortified varieties |

| De Groote and Kimenju (2008)75 | Kenya |

|

Contingent valuation in a semi-double-bounded model (acceptance of offered bids in 2 rounds) | Price, time saving, nutrient quality, and cleanliness were mentioned as factors determining choice for a particular maize product. Only 25% of respondents were willing to buy yellow maize at the same price as white maize. Acceptance increased with lower follow-up bids, with a maximum of 50%–58% of respondents being willing to pay for yellow maize at a 30% discount. Modeling showed 37% discount to be required for consumer acceptance (for supermarket respondents: 48%) | Consumers preferred white maize and would need a discount of 37% to buy yellow maize. People from western Kenya had the strongest preference for yellow maize. Consumers with higher education and income had a stronger preference for white maize. To market yellow maize for urban consumers in Nairobi, substantial price reductions would be necessary |

| De Groote et al. (2010)50 | Ghana |

|

Individual auctions (BDM) and choice experiments and group auctions after being exposed to no information and later to 5-min radio message about the benefits of eating orange maize | In Ashanti Region, consumers’ WTP is higher for white maize than for yellow and higher for yellow than for orange. In Central Region, WTP is higher for yellow than for white or orange. In the Eastern Region, WTP for yellow and orange maize is higher than for white. The difference in WTP between white and yellow maize was only significant in the Eastern Region. Provision of information increased WTP for orange maize relative to that for white maize and reduced WTP for white and yellow maize | A good information campaign based on radio message is likely to have an effect on consumer acceptance for orange maize |

| De Groote et al. (2011)79 | Kenya |

|

Experimental auction: price WTP for normal rice and willingness to buy biofortified or fortified maize for same or reduced price | Respondents were willing to pay 42.6 KES for white maize, 25% more for fortified maize, and 10% less for yellow maize. Location, familiarity with yellow maize (as in the west), and awareness raised the price by 6% and 7% for yellow maize | White maize is preferred, but WTP for fortified maize was higher and therefore with nutrition education yellow maize can be potentially accepted |

| De Groote and Kimenju (2012)80 | Kenya |