Abstract

Background. Chronic pain is a significant health problem strongly associated with a wide range of physical and mental health problems, including addiction. The widespread prevalence of pain and the increasing rate of opioid prescriptions have led to a focus on how physicians are educated about chronic pain. This critical scoping review describes the current literature in this important area, identifying gaps and suggesting avenues for further research starting from patients’ standpoint.

Methods. A search of the ERIC, MEDLINE, and Social Sciences Abstracts databases, as well as 10 journals related to medical education, was conducted to identify studies of the training of medical students, residents, and fellows in chronic noncancer pain.

Results. The database and hand-searches identified 545 articles; of these, 39 articles met inclusion criteria and underwent full review. Findings were classified into four inter-related themes. We found that managing chronic pain has been described as stressful by trainees, but few studies have investigated implications for their well-being or ability to provide empathetic care. Even fewer studies have investigated how educational strategies impact patient care. We also note that the literature generally focuses on opioids and gives less attention to education in nonpharmacological approaches as well as nonopioid medications.

Discussion. The findings highlight significant discrepancies between the prevalence of chronic pain in society and the low priority assigned to educating future physicians about the complexities of pain and the social context of those afflicted. This suggests the need for better pain education as well as attention to the “hidden curriculum.”

Keywords: Scoping Review, Medical Education, Chronic Noncancer Pain, Opioids

Introduction

Chronic pain is a significant global public health concern associated with risk of depression, anxiety, unemployment, and opioid abuse [1]. Worldwide, approximately 20% of people experience some form of pain [2]. A recent Canadian study found the prevalence of chronic pain in adults to be 18.9% [3]; using different measures, the Institute of Medicine estimates that half of all American adults live with some form of chronic pain [4]. In a study of 15 European countries and Israel, where an average prevalence of 19% was found, 61% of adults living with chronic pain reported being unable to work outside the home, 19% reported they had lost a job, and 21% reported being diagnosed with depression [5].

While chronic pain can be devastating, common treatments also carry significant risk. Addiction is a major concern, and deaths from prescription opioids are on the rise [6]. In a cohort of 32,499 patients started on chronic opioids in Ontario, Canada, between 1997 and 2010, 58 (0.2%) had succumbed to opioid-related death at the end of data collection in 2011, with a median of 2.6 years from initial prescription to death. The small subset (1.8%) of patients who were escalated to high-dose therapy were 24 times more likely to die than those who stayed on lower doses [7]. Canadian pharmacies dispensed 23% more high-dose opioids in 2006 than 2011 [8]. Prescription opioid use continued to rise in Canada, with the exception of Ontario, between 2010 and 2013 [9]. While opioids are now considered an inappropriate or less optimal treatment for many cases of chronic pain and are well-known causes of other significant health issues for patients such as addiction, our review casts a unique and important light on the history of how we arrived at what is now commonly referred to as an opioid epidemic.

Some physicians report having inadequate training in management of chronic conditions; others who underwent additional training reported it had a positive effect on their attitudes toward caring for people with chronic disease [10]. These findings have led to recommendations that medical schools and residency programs modify their curricula [10], in particular by including chronic noncancer pain training early in all residency programs, in order to foster compassion [11].

As part of a larger ethnographic study of Chronic Pain Management in Family Medicine (COPE) [12] funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, we set out to describe the current literature on chronic pain management training in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education. Going beyond typical scoping review methodologies that “map” the literature and identify gaps [13,14], we took a critical approach to scoping the literature, using a historical lens and bringing in theoretical concepts to arrive at a more contextual understanding of the body of literature we explored. This review presents a “history of the present”[15] that demonstrates at least partially how an addictive pharmacological treatment became the lynchpin of medical care for those with chronic pain. This historical emphasis on pain medication as the treatment of choice may have led to an underemphasis on the provision of alternative treatments as well as compassionate communication.

Methods

For study selection and data extraction, we relied on the team-based method recommended by Levac and colleagues [16], which builds on Arksey and O’Malley’s seminal framework for scoping reviews [14]. Given our focus on education research as well as practice, the availability of relatively recent reviews of curricula that fall within our scope [17], and our desire to engage critically with the existing research, we used a narrower scope than that recommended by Arksey and O’Malley, searching only for peer-reviewed studies and excluding grey literature.

We applied a critical, historical lens to our review in order to capture conceptual changes occurring over time and bring in contextual evidence to challenge foundational assumptions of the literature we scoped. Critical research can be seen as a means of “making strange” the assumptions of a particular field of knowledge [18]. Making strange brings to light the historically contingent power relations that coordinate daily life yet are often taken for granted in everyday conversation. Analyzing the statements, or discourses, through which knowledge is constructed enables everyday assumptions to be problematized [19]. Seeing the “everyday world as problematic” [20] enables one to imagine and make arguments about how it might be organized differently, which is a crucial step toward imagining social change. Thus, critical discourse analysis, and critical thinking in general, can be seen as both a rigorous form of analysis with deep philosophical roots and a means of imagining innovative solutions to the most pressing social problems [21]. Our critical approach proceeds from this rationale, and it is reflected in our findings, which are organized thematically according to potential lines of further critical research and avenues for change in education and practice.

Context

Although there is a vibrant tradition of critical scholarship in the social sciences, including medical education, we were unable to find guidance on how to incorporate critical perspectives into scoping reviews [13,14,16]. To address this limitation, we considered the critical approaches commonly used in other types of studies, particularly the use of historical and conceptual frameworks [18]. In recent years, Macdonald and Lang [22] have applied social science theory to interpret scoping review findings, and Martimianakis and colleagues have used team-based, critical discourse analysis methods similar to our own [23]. We see our study as another step toward scoping reviews that not only identify gaps, but interrogate the space between gaps where concepts are commonly accepted rather than met with questions such as “why” and “in whose interest?”

Literature Search

We searched ERIC and Social Sciences Abstracts using the following terms: (medical education OR curriculum) AND (chronic pain OR opioids OR analgesics). We searched MEDLINE using the following terms: medical education (graduate medical education OR undergraduate medical education OR internship and residency) OR curriculum (competency-based education OR interdisciplinary studies OR mainstreaming education OR problem-based learning) AND pain (musculoskeletal pain OR chronic pain) OR analgesics (non-narcotic analgesics OR short-acting analgesics OR narcotics OR opioid analgesics).

A further search using the broad terms (opioid OR pain OR analgesics) was conducted of 10 key journals: 1) Academic Medicine; 2) Medical Education; 3) Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice; 4) Postgraduate Medical Journal; 5) Simulation in Healthcare; 6) Advances in Physiology Education; 7) Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions; 8) Journal of Surgical Education; 9) Evaluation and the Health Professions; and 10) Medical Teacher. Reference lists of articles identified in the database search were also hand-searched for potentially relevant titles.

All titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher (SB) for primary research pertaining to undergraduate or postgraduate medical education in chronic noncancer pain. Searches were limited to articles published in English in the past 20 years. Case reports, news, editorials, and commentaries, as well as studies of training related to acute, cancer, and palliative pain management, were excluded, as were studies focused on continuing medical education in already-licensed physicians or on training in other health care professions. The primary author (FW) screened the titles and abstracts of all short-listed articles for relevance, as well as approximately 5% of all titles and abstracts to ensure concordance and quality. Articles that met the criteria for inclusion in the critical scoping review were divided among three authors (SB, FW, EO) for extraction of key data points: publication year, population, purpose, design, and intervention.

Critical Review

Once full-text articles had been filtered for relevance, the senior author and other members of the study team reviewed all articles included in the final scoping study. In a series of face-to-face meetings, the study team discussed the research findings, identifying key concepts including historical trends in the data and potential avenues for critical research. Data were then reorganized, and points related to these themes clarified with reference to the full-text articles. These thematic findings are presented alongside the descriptive results of our scoping review.

Results

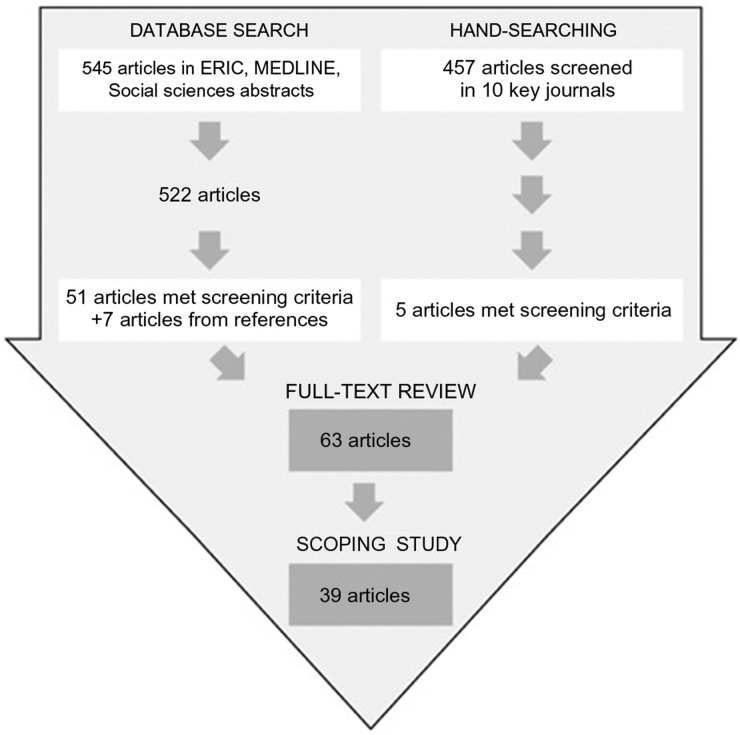

The database search identified 545 articles, 23 of which were duplicates; 51 were selected for full-text review (Figure 1), and seven more were identified from reference lists. Of 457 titles and abstracts identified in the broad search of medical education journals, five were selected for full-text review. Of the 63 articles that underwent full-text review, 39 were included in our critical scoping study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results of the modified scoping review process.

Findings are grouped into four inter-related themes: 1) the historical shift from concerns regarding opiophobia to overprescribing; 2) the inadequacy of the current chronic noncancer pain training landscape; 3) implications of training for the development of physician empathy; and 4) implications for physician well-being.

The Historical Shift from Concerns Regarding Opiophobia to Overprescribing

Our review identified a recent shift in thinking about the use of opioids. In five older papers (2000–2009), the emphasis was often on teaching medical students and residents that there was a low risk of addiction with opioid pain medications. The term “opiophobia” was sometimes employed to describe physicians who underprescribed [24,25]. Authors were concerned that the percentage of patients with chronic pain whom students believed to be drug seekers increased after clerkship [26] and that residents tended to overestimate the risk of addiction [27].

By contrast, six more recent articles (2009–2014) focused on managing the “inappropriate” prescribing of opioids and monitoring patients for signs of addiction [17,28–32], and we found no mention of “opiophobia” in this period.

Students’ understanding of opioid addiction was found to be lacking [31], as was their ability to interpret urine drug tests [28]. A curriculum review of Canadian and American medical schools critiqued the lack of education in substance abuse and addiction [17]. In 2014, Persaud found that one medical school was offering lectures supported by pharmaceutical companies without disclosing this conflict of interest to students and critiqued medical educators for downplaying the adverse effects of opioids and allowing industry to influence curriculum [32].

After participating in case-based learning aiming to identify opioid use disorder in patients with chronic noncancer pain, residents reported feeling more prepared in identifying illicit substance use [30]. When the charts of residents who participated in training for chronic pain management were reviewed, an emphasis on urine testing and documentation of discussions around use of a controlled substance was evident [29]. Hence there is some evidence that management strategies that potentially would have been considered opiophobic would now potentially be considered best practice. However, within the medical education literature, this has not been accompanied by research or commentary on the need for guidance on alternative approaches in light of the growing recognition of the drawbacks of prescribing opioids.

The current emphasis on the rise of deaths from opioids often sidesteps the important issue of why so many highly addictive and dangerous drugs were prescribed in the first place. The discursive shift from “opiophobia” to “inappropriate prescribing” highlights the inherent tensions between the widespread prevalence and debilitating effects of chronic pain, the often unacknowledged role of the pharmaceutical industry in pain-management training, and the conflicted role many physicians face between offering symptom relief with opioids and preventing addiction. Fields [33] constructs this as a “doctor’s dilemma,” contrasting the viewpoint that it would be “unconscionable to withhold adequate treatment from any patient complaining of severe pain” with the viewpoint that “addiction is a significant risk” among chronic pain patients using opioids.

The Inadequacy of the Current Chronic Pain Training Landscape

Most of the curricula were positively evaluated. However, other studies demonstrated that students became “less idealistic” about chronic pain patients during medical school [26] and performed poorly on evaluating the psychosocial sequelae of chronic pain [34]. Two studies found that the number of hours dedicated to pain management during medical school was limited and the lack of a dedicated pain course led to a fragmented training approach [17,35]. Another reported that residents were found to underuse pain scales and opioid-equivalence tables, underprescribe patient-controlled analgesia, and overestimate the risk of addiction [27]. The focus on underprescription and overestimation of the risk of addiction in this latter study, published in 2005, stands in stark contrast to contemporary concerns about overprescribing.

Twelve surveys were included in our analysis [25,26,28,31,35–41]. Of five surveys of program directors [37,38], two reported that directors believe training in chronic pain to be generally inadequate [40,42], another found directors of programs whose curricula offered little formal pain management training nonetheless reported them to be adequate [39], and the other two found that directors report chronic pain management to be of lower importance and interest to residents than other areas of study [37,38]. Meanwhile, a survey of medical students found that they report a lack of interdisciplinary training and less emphasis on the sociological issues pertaining to pain as compared with its pathophysiology [43]. Another survey found that medical students developed behaviors during training, such as increased authoritarianism, that contributed to suboptimal pain management for patients [24].

Four studies were surveys of medical residents, primarily in internal medicine [11,27,28,36]. Residents in one study reported an absence of chronic pain management teaching in medical school and residency [36]; another found residents felt it was less rewarding to work with patients with chronic noncancer pain [11].

Despite the mostly positive evaluations of curricula, the survey data indicate that students, residents, and educators consider the current training landscape to be inadequate.

It is also worth noting that the literature on pain management in medical education focuses almost exclusively on evaluations of educational outcomes and surveys of learners and educators. The limitations of this approach have been noted in other studies [44]. Few studies have assessed the impact of training on students’ clinical management of patients, with the exception of one pre- and postprescription audit [45] and one study involving evaluation of residents’ charts [29].

Twenty-one studies included in our analysis were evaluations of existing or new chronic pain curricula, 11 at the medical student level [26,34,41,45–52] and 10 at the resident level [25,27–30,53–57]. Twelve of these relied on pre- and post-tests of students’ knowledge to assess the effectiveness of curricula [25,29,30,47–49,51,53–57], while one used a multiple-choice knowledge assessment [52] and three asked students to complete a questionnaire [26–28].

The lack of educational interventions in clinical settings makes it difficult to assess the impact that educational interventions have on patient care. Meanwhile, the discrepancy between survey and post-test data suggests a need for research into the suitability of the latter approach as a standalone assessment mechanism. Given that care physicians often describe their training in pain management as poor [10], there is a clear need for further investigation of how training in pain management impacts patient-physician interactions, as well as the outcome this has on treatment approaches offered to patients.

Implications of Training for the Development of Physician Empathy

Four studies addressed the psychosocial impact of managing patients with chronic noncancer pain on medical students and residents [11,26,58,59]. Encounters with patients with chronic pain were found to have profound and often unacknowledged effects on future physicians’ attitudes toward complex patients, their role as caregivers, and the profession of medicine itself [26]. A review of reflective journals written by 86 medical students found that their opinions of chronic pain patients were mostly negative; they worried about patients’ trustworthiness and identifying those who had “true pain” vs “drug seekers” [58]. Again, this highlights the historical reliance on opioids, as the question of whether or not patients are drug seekers only becomes relevant when addictive medications are offered as standard treatment. The importance of empathy in the provision of high-quality clinical care has been frequently advocated, and yet training in “compassionate care” has been shown to be absent [60]. This review demonstrates that few articles on education in the management of chronic pain touch on this important area of research.

Implications for Physician Well-Being

Corrigan and colleagues have found that uncertainty is central to medical students' attitudes toward chronic pain patients [58]. Indeed, uncertainty is a common element of all aspects of chronic pain, and opioid treatment adds new dimensions of uncertainty. Worries about the trustworthiness of chronic pain patients and the potential of being manipulated by drug seekers suggest a profound unease with the uncertainty of pain treatment. These worries initially gave rise to the now-abandoned discourse of “opiophobia” and continue to be captured in surveys of attitudes and beliefs about chronic pain patients. Given the inadequacy of pain curricula, it is unsurprising that students find dealing with the clinical realities of chronic pain management challenging and exhausting [58]. More fundamentally, the dominance of issues surrounding opioids in discussions about pain management suggests that learners may not be receiving adequate guidance in the full range of strategies for helping patients manage pain, including both alternative forms of symptom relief and helping patients find ways to cope with the limitations of pharmacological approaches.

In addition to the risk of creating unnecessary strain in the patient-physician relationship, the lack of early and comprehensive pain education may also affect medical students' perceptions of the profession as a whole. The finding, cited above, that internal medicine residents found caring for chronic pain patients to be less rewarding than other types of medical work, was accompanied by the finding that 58% of those surveyed indicated that chronic nonmalignant pain patients negatively influenced their opinion of primary care as a career option [11]. As students become less idealistic toward the medical profession in general during training, they begin to place more faith in pharmaceutical interventions than patient-dependent therapy [26]. Aside from being an important issue in its own right, the impact of uncertainty on physician well-being is also closely related to the quality of patient care.

Discussion

Our first theme, the shift from labeling physicians as “opiophobic” when they failed to prescribe opioids to viewing those who do prescribe as “inappropriate prescribers,” requires further attention as it informs the current situation of high rates of prescription opioid use [6,7,9] and highlights the need for adequate physician training in this important area. The paucity of evidence around the impact of educational interventions on the clinical performance of students is particularly concerning given the discrepancy we found between the mostly positive results of curriculum evaluation studies and survey research indicating widespread agreement that the training landscape is inadequate.

As well as providing insights about transfer of formal training to the clinic, further investigation of chronic pain education outcomes in clinical settings could establish knowledge about how informal training affects students’ and residents’ practice and attitudes. In the medical education context, “hidden curriculum” has been used to describe the unwritten, and often unseen, “socialization process of medical training” [61]. Previous studies have demonstrated how the hidden curriculum impacts students’ behavior and affects their empathy and compassion [61].

However, our second finding, a theme of perceived inadequacy of the training landscape in much of the literature, can also be extended to the fact that research in chronic pain education largely focuses on formal training. Curriculum reviews, such as Mezei and Murinson’s extensive study [17], provide important evidence of the inadequacy of formal training, but there has not been similarly extensive investigation of the informal training landscape. This is especially problematic given the particularities of pain management, which requires compassion and the ability to sensitively communicate complex knowledge on a range of topics, from alternative treatment modalities and lifestyle changes to expectations and the limits of biomedical therapies to the risk and reality of addiction.

Fishman and colleagues’ competency-based framework [62], published in 2013, represents an important advance in developing and disseminating knowledge about the importance of openness to alternatives to pharmacology and understanding of context. We see our review, and call for further research into informal learning, as complementary to this advance. Even if all of the relevant facts are covered in an ideal curriculum, knowing when and how to draw upon them is a skill that learners necessarily develop informally, from the framing of issues in the classroom and from interactions during their clinical training. Research on the impact of the hidden curriculum on perceptions and practice with regard to chronic pain patients could complement further study of the impact of formal pain management curricula in clinical settings.

One area of particular importance for education practice and research is informal learning around the risk of addiction. Some physicians report that they fear facing sanctions as a result of prescribing opioids [63]. Primary care physicians have been found to be especially concerned with causing physical harm when prescribing opioids to their older patients, and have also identified diversion of drugs to family members as a pressing concern [64]. It has been hypothesized that increased scrutiny may lead physicians to reduce their prescribing of opioids without having access to alternative methods of pain relief, thereby undertreating chronic pain [65]. While cases of addiction and overdose death are all too real, the tone and direction of recent concerns about addiction and drug-seeking in patients with chronic pain may nonetheless reflect a moral panic [66,67] in which blame for the institutionalized lack of support and treatment is transferred to the most vulnerable actors in the social organization of care.

When this framing is uncritically accepted, inadequate medical treatment of chronic pain is redefined as being the problem of poorly behaved patients or poorly performing physicians, rather than a complex series of issues pertaining to the largely pharmaceutical-based solutions used in current practice. Among other things, informal training may reinforce perceptions that patients, especially the elderly, are at unacceptably high risk of physical harm if prescribed opioids; that patients divert their medications to addicts or are addicts themselves; and that, in many cases, complaints about pain are in fact drug-seeking behavior. These perceptions in turn lead to a sense that dealing with opioids and the patients who use them is a distinct downside of primary care practice in general, and of chronic pain management in particular. This particular finding reinforces the need for further research extending from our third theme, to address the implications of training for the development of physician empathy toward patients, as well as our fourth theme, the implications of learning and practice surrounding chronic pain for the well-being of physicians themselves.

Evidence from surveys of students’ attitudes and reflections, as well as the reflections of experienced practitioners, would seem to suggest that the cautious tone of today’s curriculum is compounded by a formidable hidden curriculum. Hidden curriculum is typically invoked in critical analyses that seek to problematize everyday phenomena, and indeed that is how we have employed the concept here. However, we are also mindful of a tendency, discussed by Martimianakis and Hafferty [68], to portray all informal socialization as an inevitable barrier to humanistic practice. This need not be the case; in reality, informal socialization is inescapable. We see hidden curriculum as a fertile ground for critical reflection on how socialization processes could be better structured and enacted.

In current medical thinking, chronic pain treatment should focus on rehabilitation rather than interventions aimed at symptom relief [69]. As chronic pain typically persists over the long term, opioid treatment involves greater risk of addiction, tolerance, and adverse events [8,70]. Accordingly, several professional organizations have provided physicians with guidelines on safe opioid prescribing to address the ambiguity faced in managing chronic pain.

However, our review suggests that medical education has barely touched on nonpharmacologic approaches to managing pain. While these are less widely researched in a medical education context and less commonly used in mainstream practice, they may offer an effective means of mitigating opioid use on an individual and societal level [71]. Conversely, if research in medical education is limited to the issues emerging from conventional practice, rather than taking a critical perspective on how issues such as over- and underprescribing are framed and what these framings leave out, there is a risk of reinforcing the tendency to conflate prescribing opiates with the humanistic imperative of helping patients manage their pain.

Research surrounding our fourth theme, implications for physician well-being, indicates that trainees find managing chronic noncancer pain stressful and emotionally taxing. An underlying etiology often cannot be found and many patients exhibit high levels of distress [69], making it difficult to apply guidelines intended to determine who should be given a prescription for acute symptom relief and who should be referred to a biopsychosocial approach. As concern about addiction and adverse events has increased, the medical profession has fallen under scrutiny. Practitioners and students worry that they have insufficient skills to identify “drug seekers” and that even “legitimate” pain patients are potential addicts or overdose deaths. As Corrigan and colleagues [58] observed, “[the topic of] ‘pain’ was painful for students.”

Given the high prevalence of chronic pain, as well as the medical and ethical importance of safely providing care to the subset of opiate users who do experience addiction, there is a clear need for research on how to teach students about chronic pain management, particularly the full range of available treatment strategies and the importance of empathy toward patients. We see our critical scoping review as a first step in identifying new avenues of research to meet this need.

Authors’ Contributions

FW conceived of the study and led the design, data collection, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. SB participated in study design and conducted data collection and analysis and drafting of the manuscript. EO participated in data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. FW, SB, EO, JK, SD, and CM participated in analysis and contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the members of the full COPE team: Onil Bhattacharyya, Aileen Davis, Rick Glazier, Paul Krueger, Ross Upshur, Albert Yee, and Lynn Wilson, who did not participate in this particular project.

References

- 1. Cheatle MD. Depression, chronic pain, and suicide by overdose: On the edge. Pain Med 2011;12(s2):S43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldberg D, McGee S.. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health 2011;11:770.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schopflocher D, Taenzer P, Jovey R.. The prevalence of chronic pain in Canada. Pain Res Manag 2011;166:445–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Institute of Medicine, Care Committee on Advancing Pain Research (and Education). Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. US National Washington, D.C.: Academies Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D.. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;104:287–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, et al. The burden of premature opioid-related mortality. Addiction 2014;1099:1482–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaplovitch E, Gomes T, Camacho X, et al. Sex differences in dose escalation and overdose death during chronic opioid therapy. PLoS One 2015;108:10–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Dhalla IA, Juurlink DN.. Trends in high-dose opioid prescribing in Canada. Can Fam Physician 2014;609:826–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murphy Y, Golder E, Fischer B.. Prescription opioid use, harms and interventions in Canada: A review update of new developments and findings since 2010. Pain Physician 2015;184:e605–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darer JD, Hwang W, Pham HH, Bass EB, Anderson G.. More training needed in chronic care: A survey of US physicians. Acad Med 2004;796:541–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yanni LM, Weaver MF, Johnson BA, et al. Management of chronic nonmalignant pain: A needs assessment in an internal medicine resident continuity clinic. J Opioid Manag 2008;44:201–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Webster F, Bhattacharyya O, Davis D, et al. An institutional ethnography of Chronic Pain Management in Family Medicine (COPE) study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015 Nov 5;15:494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grant MJ, Booth A.. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J 2009;262:91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arksey H, O’Malley L.. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;81:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foucault M. Discipline and Punish, Translated from the French b, Alan Sheridan, New York: Vintage; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK, others. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;51:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mezei L, Murinson BB.. Development JHPC, Team. Pain education in North American medical schools. J Pain 2011;1212:1199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuper A, Whitehead C, Hodges BD.. Looking back to move forward: Using history, discourse and text in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 73. Med Teach 2013;351:e849–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Foucault M. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Translated from the French b, Alan Sheridan, New York: Pantheon Books; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith DE. The Everyday World as Problematic: A Feminist Sociology. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hodges BD. When I say…critical theory. Med Educ 2014;4811:1043–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Macdonald M, Lang A.. Applying risk society theory to findings of a scoping review on caregiver safety. Health Soc Care Community 2014;222:124–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martimianakis MAT, Michalec B, Lam J, et al. Humanism, the hidden curriculum, and educational reform: A scoping review and thematic analysis. Acad Med 2015;9011:S5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weinstein SM, Laux LF, Thornby JI, et al. Medical students’ attitudes toward pain and the use of opioid analgesics: Implications for changing medical school curriculum. South Med J 2000;935:472–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scott E, Borate U, Heitner S, et al. Pain management practices by internal medicine residents—a comparison before and after educational and institutional interventions. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2008;255:431–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Griffith CH, Wilson JF.. The loss of student idealism in the 3rd-year clinical clerkships. Eval Health Prof 2001;241:61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chaitowitz M, Tester W, Eiger G.. Use of a comprehensive survey as a first step in addressing clinical competence of physicians-in-training in the management of pain. J Opioid Manag 2005;12:98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Starrels JL, Fox AD, Kunins HV, Cunningham CO.. They don’t know what they don’t know: Internal medicine residents’ knowledge and confidence in urine drug test interpretation for patients with chronic pain. J Gen Intern Med 2012;2711:1521–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith CD. A curriculum to address family medicine residents’ skills in treating patients with chronic pain. Int J Psychiatry Med 2014;474:327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gunderson EW, Coffin PO, Chang N, Polydorou S, Levin FR.. The interface between substance abuse and chronic pain management in primary care: A curriculum for medical residents. Subst Abuse 2009;303:253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ali N, Thomson D.. A comparison of the knowledge of chronic pain and its management between final year physiotherapy and medical students. Eur J Pain 2009;131:38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Persaud N. Questionable content of an industry-supported medical school lecture series: A case study. J Med Ethics 2014;406:414–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fields H. The Doctor’s Dilemma: Opiate analgesics and chronic pain. Neuron 2011;69:591–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leila NM, Pirkko H, Eeva P, Eija K, Reino P.. Training medical students to manage a chronic pain patient: Both knowledge and communication skills are needed. Eur J Pain 2006;102:167–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, Hunter J, et al. A survey of prelicensure pain curricula in health science faculties in Canadian universities. Pain Res Manag 2009;14:439–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. English WA, Nguyenvantam JS, Pearson JCG, Madeley RJ.. Deficiencies in undergraduate and pre-registration medical-training in prescribing for pain control. Med Teach 1995;172:215–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Galer BS, Keran C, Frisinger M.. Pain medicine education among American neurologists: A need for improvement. Neurology 1999;528:1710–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hagstrom AK, Leo RJ.. The status of pain medicine education in psychiatry: A survey of residency training program directors. Acad Psychiatry 2012;361:66.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ogle KS, McElroy L, Mavis B.. No relief in sight: Postgraduate training in pain management. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2008;254:292–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sengstaken EA, King SA.. Primary care physicians and pain: Education during residency. Clin J Pain 1994;104:303–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weiner DK, Morone NE, Spallek H, et al. E-learning module on chronic low back pain in older adults: Evidence of effect on medical student objective structured clinical examination performance. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;626:1161–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Weiner DK, Turner GH, Hennon JG, Perera S, Hartmann S.. The state of chronic pain education in geriatric medicine fellowship training programs: Results of a national survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;5310:1798–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Poyhia R, Niemi-Murola L, Kalso E.. The outcome of pain related undergraduate teaching in Finnish medical faculties. Pain 2005;1153:234–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Webster F, Krueger P, MacDonald H, et al. A scoping review of medical education research in family medicine. BMC Med Educ 2015;151:1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Akici A, Goren MZ, Aypak C, Terzioglu B, Oktay S.. Prescription audit adjunct to rational pharmacotherapy education improves prescribing skills of medical students. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005;619:643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mavis BE, Ogle KS, Lovell KL, Madden LM.. Medical students as standardized patients to assess interviewing skills for pain evaluation. Med Educ 2002;362:135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Watt-Watson J, Hunter J, Pennefather P, et al. An integrated undergraduate pain curriculum, based on IASP curricula, for six health science faculties. Pain 2004;1101:140–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cohen IT, Bennett L.. Introducing medical students to paediatric pain management. Med Educ 2006;405:476.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hunter J, Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, et al. An interfaculty pain curriculum: Lessons learned from six years experience. Pain 2008;1401:74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stevens DL, King D, Laponis R, et al. Medical students retain pain assessment and management skills long after an experiential curriculum: A controlled study. Pain 2009;1453:319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Puljak L, Sapunar D.. Web-based elective courses for medical students: An example in pain. Pain Med 2011;126:854–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Murinson BB, Nenortas E, Mayer RS, et al. A new program in pain medicine for medical students: Integrating core curriculum knowledge with emotional and reflective development. Pain Med 2011;122:186–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen I, Goodman B 3rd, Galicia-Castillo M, et al. The EVMS pain education initiative: A multifaceted approach to resident education. J Pain 2007;82:152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Roth CS, Burgess DJ.. Changing residents’ beliefs and concerns about treating chronic noncancer pain with opioids: Evaluation of a pilot workshop. Pain Med 2008;97:890–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sullivan MD, Gaster B, Russo J, et al. Randomized trial of web-based training about opioid therapy for chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2010;266:512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Elhwairis H, Reznich CB.. An educational strategy for treating chronic, noncancer pain with opioids: A pilot test. J Pain 2010;1112:1368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Evans L, Whitham JA, Trotter DR, Filtz KR.. An evaluation of family medicine residents’ attitudes before and after a PCMH innovation for patients with chronic pain. Fam Med 2011;4311:702–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Corrigan C, Desnick L, Marshall S, Bentov N, Rosenblatt RA.. What can we learn from first-year medical students’ perceptions of pain in the primary care setting? Pain Med 2011;128:1216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Murinson BB, Agarwal AK, Haythornthwaite JA.. Cognitive expertise, emotional development, and reflective capacity: Clinical skills for improved pain care. J Pain 2008;911:975–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Whitehead C, Kuper A, Freeman R, Grundland B, Webster F.. Compassionate care? A critical discourse analyses of accreditation standards. Med Educ 2014;486:632–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bandini J, Mitchell C, Epstein-Peterson ZD, et al. Student and faculty reflections of the hidden curriculum: How does the hidden curriculum shape students’ medical training and professionalization? Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2017 Feb;341:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fishman SM, Young HM, Lucas Arwood E, et al. Core competencies for pain management: Results of an interprofessional consensus summit. Pain Med 2013;147:971–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wolfert MZ, Gilson AM, Dahl JL, Cleary JF.. Opioid analgesics for pain control: Wisconsin physicians’ knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and prescribing practices. Pain Med 2010;113:425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Spitz A, Moore AA, Papaleontiou M, et al. Primary care providers’ perspective on prescribing opioids to older adults with chronic non-cancer pain: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr 2011 Jul 14;11:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dickinson BD, Altman RD, Nielsen NH, Williams MA.. Use of opioids to treat chronic, noncancer pain. West J Med 2000;1722:107–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cohen S. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers. London: MacGibbon and Kee; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Goode E, Ben-Yehuda N.. Moral panics: Culture, politics, and social construction. Annu Rev Social 1994;20:149–71. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Martimianakis MA, Hafferty FW.. Exploring the interstitial space between the ideal and the practised: Humanism and the hidden curriculum of system reform. Med Educ 2016;503:278–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Grichnik KP, Ferrante FM.. The difference between acute and chronic pain. Mt Sinai J Med 1991;583:217–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: A systematic review for a national institutes of health pathways to prevention workshop. Ann Intern Med 2015;1624:276–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cunningham N, Kashikar-Zuck S.. Nonpharmacologic treatment of pain in rheumatic diseases and other musculoskeletal pain conditions. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2013;15:306.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]