Abstract

Adolescent girls are at substantial risk of sexually transmitted diseases including HIV. To reduce these risks, we developed Health Education And Relationship Training (HEART), a web-based intervention focused on developing sexual assertiveness skills and enhancing sexual decision-making. This study assessed the feasibility and acceptability of this new program and examined if perceived acceptability varied according to participant ethnicity, sexual orientation or sexual activity status. Participants were part of a randomized controlled trial of 222 10th-grade girls (Mage = 15.26). The current analyses included those in the intervention condition (n = 107; 36% white, 27% black and 29% Hispanic). HEART took approximately 45 min to complete and was feasible to administer in a school-based setting. Participants found the program highly acceptable: 95% liked the program and learned from the program, 88% would recommend the program to a friend and 94% plan to use what they learned in the future. The primary acceptability results did not vary by the ethnicity, sexual orientation or sexual activity status of participants, suggesting broad appeal. Results indicate that this new online program is a promising method to reach and engage adolescents in sexual health education.

Introduction

Adolescent girls in the United States are at heightened risk for sexual health problems including HIV/AIDS, other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and unintended pregnancy [1, 2]. As many as one in four sexually active adolescent girls has an STD, with HPV being the most prevalent [3], and nearly 250 000 adolescent girls give birth each year, with many more becoming pregnant unintentionally and terminating the pregnancy [2]. Girls may also experience serious long-term consequences from STDs, particularly when they are left untreated. These include the risk of ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility and cervical cancer [4–6]. Identifiying effective and engaging intervention strategies to enhance adolescent girls’ sexual health practices that can be broadly disseminated is critical for improving adolescent girls’ sexual health.

One set of important skills that interventions must target to improve adolescents’ abilities to make healthy sexual choices are sexual communication skills. Sexual communication about topics such as condoms, STDs and partner history is one of the strongest predictors of safer sexual behavior [7, 8]. A recent meta-analysis has shown sexual communication between sexual partners promotes consistent condom use among young people [9]. Although open communication about sexual topics is embarrassing and uncomfortable for many youth [10, 11], communication skills can improve with training and practice [12, 13]; this makes sexual communication an ideal target for behavioral interventions.

There are a number of in-person, evidence-based interventions for adolescents that target the development of sexual communication skills [14–18]; however, notably fewer prevention programs for adolescents target communication skills using interactive, electronic health (eHealth) approaches [19]. We located seven eHealth programs that include communication skills development in their curricula; however, only two of these studies directly assessed communication skills development in samples that included adolescent girls [20, 21]. eHealth programs use technology-based platforms (e.g. computers, tablets and smartphones) as the primary mechanism for reaching and engaging youth in sexual health education and HIV/STD prevention. Compared with traditional face-to-face intervention approaches, eHealth programs offer a host of benefits including the ease and low cost of administration and increased fidelity of intervention delivery [22, 23]. In addition, content in eHealth programs can be individually tailored and highly interactive and engaging for participants. Given the nearly ubiquitous use of technology among young people [24], eHealth approaches are also highly relevant for youth.

To address the need for an innovative and effective eHealth sexual communication skills training program, our team developed Project Health Education And Relationship Training (HEART; ProjectHEARTforGirls.com). Project HEART provides comprehensive sex education and focuses on developing sexual communication skills to reduce the risk of HIV/STDs and unplanned pregnancy among youth. We designed the program to be completed in less than an hour without extensive teacher/facilitator training, making it a potentially useful supplement to many school-based sexual health curricula. The purpose of the current study was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of this program among an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse school-based sample of adolescent girls recruited as part of an ongoing clinical trial. Additionally, this study examined whether the acceptability of the program varied based on participant characteristics including ethnicity, sexual orientation and sexual activity status. This information can be used to guide future adaptations of the program.

Materials and methods

Description of the intervention

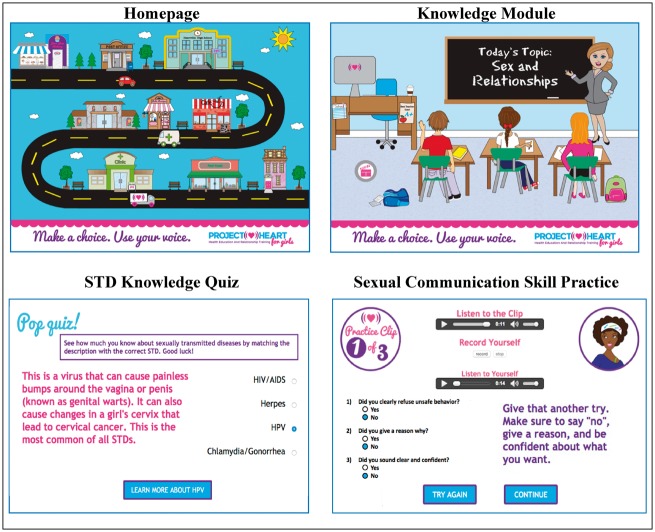

While the intervention has been described in detail elsewhere [25], a brief review is included here. Project HEART is an interactive, skills-focused intervention that is grounded in psychological and health behavior change theories, including the reasoned action model [26] and fuzzy trace theory [27]. The intervention style, content and functionality were developed with the assistance of a community advisory board of five adolescent girls who met monthly with program staff during the intervention development process. As shown in Fig. 1, the home page resembles a town with a series of five active buildings that girls enter to receive program content. Each building aims to enhance one of the five theory-based areas of sexual decision-making: (i) safer sex motivation, (ii) HIV/STD knowledge, (iii) sexual norms/attitudes;, (iv) safer sex self-efficacy and (v) sexual communication skills. At the doorway to each building, participants complete a screening quiz with corrective feedback. For example, at the entrance to the building focused on knowledge, there is a five-item true/false quiz related to HIV/STD knowledge. For any item that a participant gets incorrect, the correct answer is given in a positively framed, encouraging way. Once inside the building, participants can engage with age-appropriate material in the form of audio/video clips, tips from other adolescent girls, interactive games and quizzes, colorful infographics and skill-building exercises that include self-feedback given in real time (Fig. 1). In addition, when a participant answers incorrectly to any item on a screening quiz, the program uses branching logic to provide the participant with an additional link to ‘bonus’ content within that building. This added content is focused on remedial learning and motivation enhancement, such as an added audio or video clip. This type of tailoring based on participant responses has been shown to enhance program efficacy in HIV/STD prevention programs [28].

Fig. 1.

Sample images from ProjectHeartForGirls.com.

While the importance of sexual communication skills is addressed throughout the program, the communication module focuses specifically on building communication self-efficacy and skills. This module was designed to enhance sexual assertiveness skills and sexual negotiation skills to prepare adolescent girls to confidently and firmly refuse unprotected intercourse and work together with their partners to agree upon safer sex outcomes [29–31]. In addition to didactic training and modeling from same-age peers, participants are given time to practice sexual communication skills through an audio recording and playback feature in the site (e.g. girls respond to hypothetical scenarios depicting sexual pressure from a partner, record their own responses and then listen to and rate the response; see example in Fig. 1).

Participants

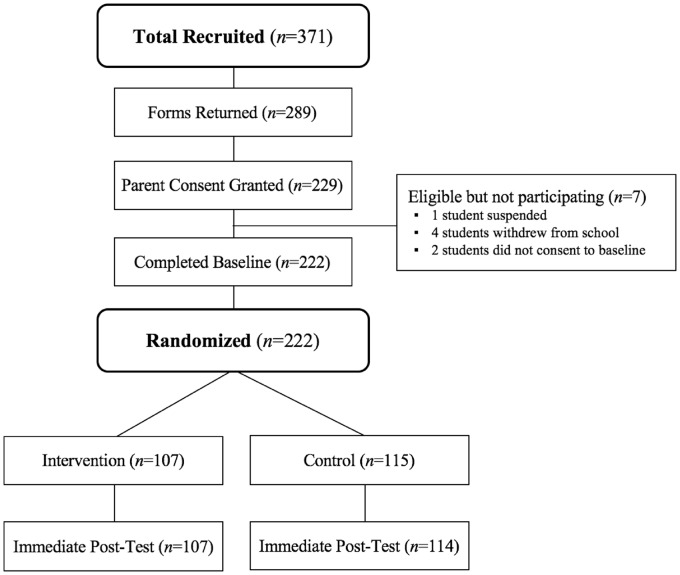

Information regarding the feasibility and acceptability of the Project HEART web program has come from an ongoing randomized controlled trial (clinical trial registration number NCT02579135). In Autumn 2015, participants were recruited from four rural, low-income high schools in the southeastern United States. All 371 10th-grade girls attending these schools at the time of the study were invited to participate. Because all students were minors under 18 years old, written parental consent and written student assent were obtained, as per US research standards [32]. As indicated in the study flow diagram (Fig. 2), 78% of youth returned a parental consent form and 79% of those parents granted consent for their daughter to participate in the study. Thus, the final sample included 222 girls who completed the baseline assessment and were randomized to study conditions (60% overall recruitment—a rate comparable to similar school-based samples; [33]). For the current study, data collected among the 107 girls who were randomized to the Project HEART intervention condition are reported.

Fig. 2.

Study flow diagram for randomized controlled trial of ProjectHEARTforGirls.com.

Study design and procedures

After parental consent and student assent were obtained, baseline data were collected using computerized surveys in a classroom setting. Next, participants were randomly assigned to either the Project HEART web program or to an attention-matched control web program focused on cultivating academic growth mindsets [34, 35]. Random assignment to study condition was conducted using random sampling and allocation procedures in SPSS version 22. Participants were stratified based on school and sexual activity status. Then, over the course of approximately 6 weeks, each participant individually completed the web-based intervention in a private school room. Research study staff coordinated with school personnel to have youth complete the program during one of their elective courses. Participants used headphones to listen to program content and to control for any outside noise.

Immediately following the intervention, participants completed a computerized post-test survey to assess their perceptions of program acceptability. This survey also gathered data on intervention outcomes, which are the focus of the ongoing clinical trial. This included information on sexual communication intentions, safer sex self-efficacy, HIV/STD knowledge, condom attitudes and norms and condom intentions [14, 36, 37], along with sexual communication skills, based on recorded responses from a behavioral task [38, 39].

Participants were compensated $10 (USD) for returning their parental consent form (regardless of whether or not consent was granted), $10 for the baseline assessment and $30 for the intervention and immediate post-test assessment. The university institutional review board approved all study procedures.

Measures

Participant characteristics

Demographic data was collected on participant age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, parent marital status and parent educational status (a proxy for socioeconomic status). Sexual activity status was assessed with two items: one that inquired whether participants had ever engaged in any sexual activity including sexual touching, oral sex and/or intercourse and a second that inquired whether participants had ever engaged in vaginal intercourse, defined for participants as ‘when a boy puts his penis in a girl’s vagina.’ Additionally, among those who reported sexual activity, information was gathered about condom use at last sex and history of pregnancy.

Feasibility

Feasibility of the program was documented through (i) study enrollment and completion rates, (ii) the time each participant took to complete the program, (iii) the number of technical problems that arose during study implementation and (iv) the strategies used and challenges of implementing the program in a school-based setting.

Acceptability

Program acceptability was assessed through a questionnaire that was adapted from prior acceptability surveys [18, 40, 41]. Specifically, six items were included to assess six aspects of acceptability: (i) an intent to return to the website, (ii) whether one would recommend the program to a friend, (iii) whether one would use information from the program in the future, (iv) how much one liked the program, (v) how much one learned from the program and (vi) how much one felt the program kept their attention. The first three questions were coded with dichotomous response options (yes/no—unsure), whereas the last three items used a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 4 = a lot. In addition, participants reported whom they planned to talk with about the information they learned in the program in the next 3 months.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Sample descriptives are included in Table I. All participants were between the ages of 14 and 17 (M = 15.26; standard deviation [SD] = 0.48), and the sample was ethnically diverse (36% white, 27% black, 29% Hispanic and 7% other ethnic identities). Approximately 50% of the participants’ parents had a high school education or less. Seventy-nine percent of girls identified as heterosexual, 12% as bisexual, 4% as lesbian and 4% as unsure or other sexual orientation. Further, 40% of girls were sexually active and nearly one-quarter had engaged in vaginal sex.

Table I.

Sample characteristics for girls in the ProjectHEARTforGirls.com intervention

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 38 (36) |

| Black | 29 (27) |

| Hispanic | 31 (29) |

| Other | 8 (7) |

| Age—m (SD) | 15.26 (0.48) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 84 (79) |

| Bisexual | 13 (12) |

| Lesbian | 4 (4) |

| Other | 6 (6) |

| Parent education | |

| Mother high school or less | 50 (47) |

| Father high school or less | 54 (51) |

| Sexual behavior | |

| Engaged in any sexual activity | 43 (40) |

| Had vaginal sex | 25 (24) |

| Used condom at last sex | 15 (60)a |

| Ever been pregnant | 1 (1) |

n = 107.

Percentage based on sexually active teens.

Feasibility

In general, the program was highly feasible to administer. Our study team worked closely with school personnel to reserve classrooms for data collection and arrange data collection during elective courses. All procedures were completed during the school day within one academic period. Our research team worked in teams of two, so that one research assistant could pull a student from their class and escort them to the testing room and the other research assistant could have the computer set up and logged in to the website. Although the majority of sessions proceeded smoothly, five sessions were interrupted by fire drills or school-wide announcements that required participants to momentarily stop the program and adhere to school guidelines. In these instances, participants returned to the program as soon as it was appropriate (generally within 10 min). In a few other instances, teachers mistakenly entered the room during a session. Participants were prompted to continue with the program once teachers left.

Ninety-two percent of participants completed the full program dose, with the majority completing it in 30–60 min (average time = 44 min). Four girls completed the program in less than 30 min due to temporary slowness in internet connection speed that allowed them to skip a module inadvertently (three participants skipped the communication module and one participant skipped both the motivation and knowledge modules). Further, five girls took more than 60 min to complete the program (max time = 77 min), likely due to inattention or slower processing speed. Of note, there were no significant differences in any rating of program acceptability based on the amount of time it took girls to complete the program.

Program acceptability

Overall, girls found the program to be highly acceptable (see Table II). Specifically, 79% of participants reported they would come back to the website again, 88% would recommend the program to a friend and 94% plan to use the information they learned in the future. Additionally, when asked if they liked the program, learned from the program and felt the program kept their attention, no participants reported ‘not at all’ and less than 5% reported ‘a little’ to these items. The remaining 95% of girls reported ‘some’ or ‘a lot’ for these items about program likability, learning and attention. The percentage of participants who reported ‘a lot’ for each item is reported in Table II.

Table II.

Acceptability of ProjectHEARTforGirls.com in full sample and by subgroup

| Full sample | Black | Hispanic | White | χ2 | Heterosexual | Nonheterosexual | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % yes (n) | % yes (n) | % yes (n) | % yes (n) | % yes (n) | % yes (n) | |||

| Would return to site | 79 (84) | 83 (24) | 87 (27) | 71 (27) | 2.96 | 80 (67) | 74 (17) | 0.37 |

| Recommend to friend | 88 (94) | 93 (27) | 87 (27) | 90 (34) | 0.60 | 88 (74) | 87 (20) | 0.02 |

| Use information in future | 94 (101) | 97 (28) | 97 (30) | 95 (36) | 0.22 | 94 (79) | 96 (22) | 0.09 |

| Liked program a lot | 56 (60) | 55 (16) | 55 (17) | 55 (21) | 0.00 | 58 (49) | 48 (11) | 0.81 |

| Learned a lot | 75 (80) | 83 (24) | 68 (21) | 68 (26) | 2.20 | 79 (66) | 61 (14) | 3.00 |

| Program kept attention a lot | 65 (69) | 55 (16) | 68 (21) | 66 (25) | 1.19 | 68 (57) | 52 (12) | 1.94 |

| Plan to discuss program with | ||||||||

| Dating partners | 65 (69) | 72 (21) | 68 (21) | 61 (23) | 1.08 | 67 (56) | 57 (13) | 0.81 |

| Best friend | 83 (89) | 72 (21)a | 94 (29)b | 90 (34)b | 6.18* | 87 (73)a | 70 (16)b | 3.88* |

| Other friends/peers | 55 (59) | 52 (15) | 55 (17) | 55 (21) | 0.09 | 51 (43) | 70 (16) | 2.47 |

| Mom | 50 (53) | 48 (14) | 45 (14) | 50 (19) | 0.16 | 54 (45) | 35 (8) | 2.55 |

| Dad | 12 (13) | 10 (3) | 7 (2) | 21 (8) | 3.47 | 12 (10) | 13 (3) | 0.02 |

| Someone else | 34 (36) | 28 (8) | 36 (11) | 42 (16) | 1.51 | 36 (30) | 26 (6) | 0.75 |

Different superscripts within a subgroup indicate significant differences between groups. For comparisons by ethnicity, nine participants who did not identify as black, white or Hispanic were removed. Also, no significant differences were observed between sexually active and nonsexually active participants (all Ps > 0.20); thus, results are not reported here.

P < .05.

Additionally, all but one participant (106 of 107) reported they would discuss the information they learned in the ProjectHEARTforGirls.com web program with someone in the next 3 months. A majority of girls planned to discuss program material with best friends (89%) and dating partners (69%). Further, 50% of participants planned to discuss the program with their mothers, whereas only 12% reported they would discuss the program with their fathers. A further breakdown of these results is presented in Table II.

Examining differences by ethnicity, sexual orientation and sexual activity status

To determine the extent to which the intervention was acceptable for subgroups of girls, a series of χ2 tests were conducted to examine differences in perceived acceptability by ethnicity, sexual orientation and sexual activity status. Very few significant differences were noted between groups. As shown in Table II, there was one group difference by ethnicity: compared with Caucasian and Hispanic girls, African American girls indicated that they would be less likely to discuss the information they learned from the program with their best friends. Further, there was one group difference by sexual orientation: compared with nonheterosexual youth, girls who identified as heterosexual were more likely to report intentions to discuss the program with a best friend (P < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in any other acceptability findings, and no significant differences were observed between sexually active and nonsexually active participants (all Ps > 0.20).

Discussion

eHealth interventions for youth have shown promise in reducing HIV, other STDs and unintended pregnancy [19], but few of these have focused on building the sexual communication and negotiation skills that we know are so important for girls’ sexual decision-making [9]. The purpose of the current study was to examine the feasibility and acceptability of a new program—ProjectHEARTforGirls.com—that targets sexual communication skills in a tailored, interactive, theory-based web program for adolescent girls. The program can be completed in approximately 45 min and is ideal for school settings where teacher time and expertise may be limited to deliver sexual health content to students.

Overall, the program was feasible to administer in a school-based setting and users found the web program to be highly engaging and acceptable. Approximately 90% of girls reported they would recommend the program to a friend, discuss the program with others and use what they learned in the future. Additionally, over 75% reported they learned a lot and would return to the site again if given the opportunity. Given the inherent challenges in engaging youth and sustaining their attention with educational content [42], we believe these results are extremely promising.

Importantly, few differences were found in ratings of acceptability between participants of different ethnicities, sexual orientations and sexual activity levels, suggesting that this program has broad appeal. We designed the program with input from a diverse group of adolescent advisors and attempted to create a program that would be highly inclusive. The acceptability findings are promising for future use of this program in diverse samples of middle adolescent girls. It is worth noting that participants were compensated for their participation in this study. While the amount of compensation is comparable to other interventions with youth in the United States, it is possible that this compensation increased participant positivity and program acceptance ratings [43].

As the focus of this program was to enhance sexual communication skills, it also was promising that nearly all girls (99%) who completed this program intended to talk with someone about the information they learned. Best friends were the most common person with whom participants planned to communicate, which is in line with previous work showing that friends are common sources of information and discussion about sex for youth [33, 44]. However, whereas over 80% of youth planned to talk with a best friend and over half planned to talk with a dating partner or their mother about the sexual health information they had learned, only 12% of girls intended to discuss the sexual health program with their fathers. Adolescent girls consistently report talking more with their mothers about sexual topics than their fathers [45, 46]; yet, fathers can provide important health information to daughters when they seize this opportunity [47, 48]. Additional research is needed to understand the barriers to father–daughter communication and to further enhance parent–child communication about sexual health [49, 50].

Finally, it should be acknowledged that after the intervention, at least two participants anecdotally noted that they were uncertain how to answer some questions within the program and outcome assessment because they did not date boys. While we attempted to make the program inclusive of sexual minority youth, for example, using gender-neutral terms like ‘dating partner’, the program was geared most heavily toward girls who have male partners. While the transmission of STDs, including HIV, is more likely to occur among girls with male partners than female partners [1], it is critical that sexual minority youth—who comprised over 20% of the current sample—are also able to receive comprehensive, inclusive, evidence-based sexual health education. It is also important that intervention efforts focus not only on girls but also on adolescent boys, particularly minority youth who are at disproportionate risk for HIV infection [51]. These are exciting and important directions for future adaptations of the Project HEART web program, so that it is effective and inclusive of all youth.

Conclusion

This article describes the initial acceptability evaluation for a new web-based intervention to increase sexual communication skills and decrease risk for STD/HIV among adolescent girls—ProjectHEARTforGirls.com. eHealth interventions are a promising approach to delivering timely and engaging sexual health information to young people [52]. Results demonstrate that the program was feasible to administer in a school-based setting and was highly acceptable to adolescent girls.

Funding

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health (R00 HD075654, K24 HD069204); NC State College of Humanities and Social Sciences Research Office; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410). Funding for technical expertise: University of North Carolina CHAI Core, a National Institutes of Health funded facility (P30 DK56350, P30 CA16086).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual Risk Behavior: HIV, STD, & Teen Pregnancy Prevention, 2017. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/sexualbehaviors/. Accessed: 21 June 2017.

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Teen Pregnancy, 2017. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/index.htm. Accessed: 21 June 2017.

- 3. Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR. et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics 2009; 124:1505–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2007, 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats07/trends.pdf. Accessed: 21 June 2017.

- 5. Monk BJ, Tewari KS.. The spectrum and clinical sequelae of human papillomavirus infection. Gynecol Oncol 2007; 107:S6–S13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haggerty CL, Gottlieb SL, Taylor BD. et al. Risk of sequelae after Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in women. J Infect Dis 2010; 201 Suppl:S134–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/652395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sheeran P, Abraham C, Orbell S.. Psychosocial correlates of heterosexual condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 1999; 125:90–132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noar SM, Carlyle K, Cole C.. Why communication is crucial: meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. J Health Commun 2006; 11:365–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730600671862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Widman L, Noar SM, Choukas-Bradley S. et al. Adolescent sexual health communication and condom use: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2014; 33:1113–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/hea0000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anderson M, Kunkel A, Dennis MR.. ‘Let’s (not) talk about that’: bridging the past sexual experiences taboo to build healthy romantic relationships. J Sex Res 2011; 48:381–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2010.482215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA.. Affairs of the heart: qualities of adolescent romantic relationships and sexual behavior. J Res Adolesc 2010; 20:983–1013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hargie O. Skilled Interpersonal Communication: Research, Theory and Practice. London: Taylor & Francis, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ogilvy CM. Social skills training with children and adolescents: a review of the evidence on effectiveness. Educ Psychol 1994; 14:73–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0144341940140105. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brown LK, Hadley W, Donenberg GR. et al. Project STYLE: a multisite RCT for HIV prevention among youths in mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2014; 65:338–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sales JM, Lang DL, DiClemente RJ. et al. The mediating role of partner communication frequency on condom use among African American adolescent females participating in an HIV prevention intervention. Health Psychol 2012; 31:63–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0025073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF. et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 292:171–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hovell MF, Blumberg EJ, Liles S. et al. Training AIDS and anger prevention social skills in at-risk adolescents. J Couns Dev 2001; 79:347–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01980.x. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Braverman PK. et al. HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005; 159:440–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ch�vez NR, Shearer LS, Rosenthal SL.. Use of digital media technology for primary prevention of STIs/HIV in youth. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014; 27:244–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peskin MF, Shegog R, Markham CM. et al. Efficacy of it’s your game-tech: a computer-based sexual health education program for middle school youth. J Adolesc Health 2015; 56:515–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roberto AJ, Zimmerman RS, Carlyle KE. et al. A computer-based approach to preventing pregnancy, STD, and HIV in rural adolescents. J Health Commun 2007; 12:53–76.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730601096622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rapoff MA. E-health interventions in pediatrics. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 2013; 1:309–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000038. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lightfoot M. HIV prevention for adolescents: where do we go from here? Am Psychol 2012; 67:661–71.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lenhart A. Teens, Social Media, and Technology Overview, 2015. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/. Accessed: 21 June 2017.

- 25. Widman L, Golin CE, Noar SM. et al. ProjectHeartForGirls.com: Development of a web-based HIV/STD prevention program for adolescent girls emphasizing sexual communication skills. AIDS Educ Prev 2016; 28:365–77. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.5.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fishbein M, Ajzen I.. Predicting and Changing Behavior. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reyna VF. A theory of medical decision making and health: fuzzy trace theory. Med Decis Making 2008; 28:850–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272989X08327066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS.. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull 2007; 133:673–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edgar T, Noar SM, Murphy B.. Communication skills training in HIV prevention interventions In: Edgar T, Noar SM, Freimuth VS (eds). Communication Perspectives on HIV/AIDS for the 21st Century. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, 2008, 29–65. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morokoff PJ, Quina K, Harlow LL. et al. Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS) for women: development and validation. J Pers Soc Psychol 1997; 73:790–804. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Noar SM, Morokoff PJ, Harlow LL.. Condom negotiation in heterosexually active men and women: development and validation of a condom influence strategy questionnaire. Psychol Health 2002; 17:711–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0887044021000030580. [Google Scholar]

- 32. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Research with Children FAQs, 2017. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/faq/children-research/. Accessed: 21 June 2017.

- 33. Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Helms SW. et al. Sexual communication between early adolescents and their dating partners, parents, and best friends. J Sex Res 2014; 51:731–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.843148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burnette JL, Finkel EJ.. Buffering against weight gain following dieting setbacks: an implicit theory intervention. J Exp Soc Psychol 2012; 48:721–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.020. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dweck CS. Self-theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Donenberg GR, Emerson E, Bryant FB. et al. Understanding AIDS-risk behavior among adolescents in psychiatric care: links to psychopathology and peer relationships. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:642–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Basen-Engquist K, M�sse LC, Coyle K. et al. Validity of scales measuring the psychosocial determinants of HIV/STD-related risk behavior in adolescents. Health Educ Res 1999; 14:25–38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/her/14.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jaworski BC, Carey MP.. Effects of a brief, theory-based STD-prevention program for female college students. J Adolesc Health 2001; 29:417–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016 /S1054-139X(01)00271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. St. Lawrence JS, Brasfield TL, Shirley A. et al. Cognitive-behavioral intervention to reduce African American adolescents’ risk for HIV infection. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995; 63:221–37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.63.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bauermeister JA, Pingel ES, Jadwin-Cakmak L. et al. Acceptability and preliminary efficacy of a tailored online HIV/STI testing intervention for young men who have sex with men: the get connected! Program. AIDS Behav 2015; 19:1860–74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1009-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paiva AL, Lipschitz JM, Fernandez AC. et al. Evaluation of the acceptability and feasibility of a computer-tailored intervention to increase human papillomavirus vaccination among young adult women. J Am Coll Health 2014; 62:32–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2013.843534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. National Research Council. Engaging Schools: Fostering High School Students’ Motivation to Learn. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Singer E, Ye C.. The use and effects of incentives in surveys. Ann Am Acad Political Social Sci 2012; 645:112–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177 /0002716212458082. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lefkowitz ES, Boone TL, Shearer CL.. Communication with best friends about sex-related topics during emerging adulthood. J Youth Adolesc 2004; 33:339–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000032642.27242.c1. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sneed CD, Somoza CG, Jones T. et al. Topics discussed with mothers and fathers for parent–child sex communication among African-American adolescents. Sex Educ 2013; 13:450–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2012.757548. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wright PJ. Father-child sexual communication in the United States: a review and synthesis. J Family Commun 2009; 9:233–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15267430903221880. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hutchinson MK, Cederbaum JA.. Talking to daddy’s little girl about sex: daughters’ reports of sexual communication and support from fathers. J Family Issues 2010; 32:550–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0192513x10384222. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wright PJ, Randall AK, Arroyo A.. Father–daughter communication about sex moderates the association between exposure to MTV’s 16 and pregnant/teen mom and female students’ pregnancy-risk behavior. Sexuality & Culture 2013; 17:50–66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12119-012-9137-2. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Noar SM. et al. Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2016; 170:52–61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Lee J. et al. Paternal influences on adolescent sexual risk behaviors: a structured literature review. Pediatrics 2012; 130:e1313–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among Youth, 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/. Accessed: 21 June 2017.

- 52. Noar SM, Harrington NG (eds). eHealth Applications: Promising Strategies for Behavior Change. New York, NY: Routledge, 2012 [Google Scholar]