Abstract

A Health in All Policies approach requires creating and sustaining intersectoral partnerships for promoting population health. This scoping review of the international literature on partnership functioning provides a narrative synthesis of findings related to processes that support and inhibit health promotion partnership functioning. Searching a range of databases, the review includes 26 studies employing quantitative (n = 8), qualitative (n = 10) and mixed method (n = 8) designs examining partnership processes published from January 2007 to June 2015. Using the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning as a theoretical framework for analyzing the findings, nine core elements were identified that constitute positive partnership processes that can inform best practices: (i) develop a shared mission aligned to the partners’ individual or institutional goals; (ii) include a broad range of participation from diverse partners and a balance of human and financial resources; (iii) incorporate leadership that inspires trust, confidence and inclusiveness; (iv) monitor how communication is perceived by partners and adjust accordingly; (v) balance formal and informal roles/structures depending upon mission; (vi) build trust between partners from the beginning and for the duration of the partnership; (vii) ensure balance between maintenance and production activities; (viii) consider the impact of political, economic, cultural, social and organizational contexts; and (ix) evaluate partnerships for continuous improvement. Future research is needed to examine the relationship between these processes and how they impact the longer-term outcomes of intersectoral partnerships.

Keywords: partnerships, literature review, intersectoral partnerships, health policy

INTRODUCTION

Intersectoral action and healthy public policy are integral elements of promoting population health and health equity (WHO, 1986, 1988, 2013). The Helsinki Statement on Health in All Policies (HiAP) (WHO, 2013) takes into account the health implications of policy decisions across all sectors and levels of government. Creating and sustaining intersectoral partnerships is a core element of implementing a HiAP approach to health promotion. This includes engaging partners from other sectors, identifying opportunities for collaboration, negotiating agendas, mediating different interests and promoting synergy (WHO, 2014). The HiAP Framework for Country Action (WHO, 2014) acknowledges that the requisite knowledge and skills for facilitating effective partnerships across sectors need to be developed. The Framework highlights the importance of monitoring and evaluation to gather evidence on what works and why, and to identify challenges and best practices.

Partnerships can be defined as collaborative working relationships where partners can achieve more by working together than they can on their own (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008; Jones and Barry, 2011a). Effective partnerships produce synergy when the complementary skills, resources, perspectives and shared know-how of the partners lead to more effective solutions (Jones and Barry, 2011b). Partnership working, however, can be challenging and may result in failure (Barile et al., 2012; Gray et al., 2012; Aveling and Jovchelovitch, 2014), It is crucial that implementing a cross-sectoral partnership approach builds on what is already understood about effective processes. The purpose of this article is to undertake a scoping review of the processes that support and inhibit health promotion partnership functioning, which have been identified in the international literature.

BACKGROUND

While numerous terms can describe collaborative work (e.g. alliance, coalition, consortium), this article uses the term “partnership” to encompass any arrangement in which people and/or organizations join together to promote health (Weiss et al., 2002). In recent years, reviews of the literature on collaborative partnerships for health have sought to better understand the processes and outcomes of such arrangements on population health. Roussos and Fawcett (Roussos and Fawcett, 2000) conducted a narrative review of the published evidence of population-level behavior change and health outcomes, community/systems change and the factors associated with these effects. Examining 34 studies on the effects of 252 partnerships, the authors highlight several factors that influence the impact of partnerships on population health: a clear mission and vision, collaborative action planning for community and systems change, developing and supporting leadership, documenting and collecting feedback, technical support, adequate financial support and making the outcomes of the work relevant to stakeholders (Roussos and Fawcett, 2000).

A more recent review, based on a combination of personal experience and a narrative review methodology, drew similar conclusions (Koelen et al., 2008). The authors divided their findings into processes that help to achieve coordinated actions and those that help sustain such actions. In the first category, the authors identified the importance of having representation from all relevant sectors including community stakeholders, discussion of aims and objectives and discussion of roles and responsibilities. Factors supporting sustainability were communication, infrastructure, visibility and management. While these reviews help to highlight important factors for assessing elements of partnership functioning, there is a paucity of research in the field of health promotion partnerships that examines which processes lead to supportive or negative partnership functioning and how these processes relate to specific partnership outputs and outcomes.

This study builds on previous reviews by examining the partnership processes described in the literature published since 2007, summarizing the findings and identifying those processes found to support and/or inhibit health promotion partnership functioning. Identifying such processes could usefully inform future studies in examining which processes contribute to successful partnership outputs and outcomes.

Theoretical framework

While there is no universally agreed-upon theory of health promotion partnership, there is a growing body of research on partnership functioning, as well as numerous proposed theoretical frameworks (Roussos and Fawcett, 2000; Lasker et al., 2001; Butterfoss and Kegler, 2009; Koelen et al., 2012). There is also a parallel body of theoretical work and empirical research in the public management literature that relates more broadly to collaborative networks (Turrini et al., 2010; Lucidarme et al., 2014).

The Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning (BMCF) (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008) is one of the few theoretical frameworks developed and empirically tested in a number of diverse health promotion initiatives. This model provides an analytical frame for examining collaborative working arrangements (Endresen, 2007; Dosbayeva, 2010; Corbin et al., 2012, 2013; Corwin et al., 2012). Researchers have chosen to use the BMCF as a guide for practice (Haugstad, 2011; Corbin et al., 2012) and as an evaluation tool (Amaral-Sabadini et al., 2012; Corbin et al., 2015) for health promotion partnerships because of its focus on the processes of partnership and its acknowledgement of both negative and positive interactions.

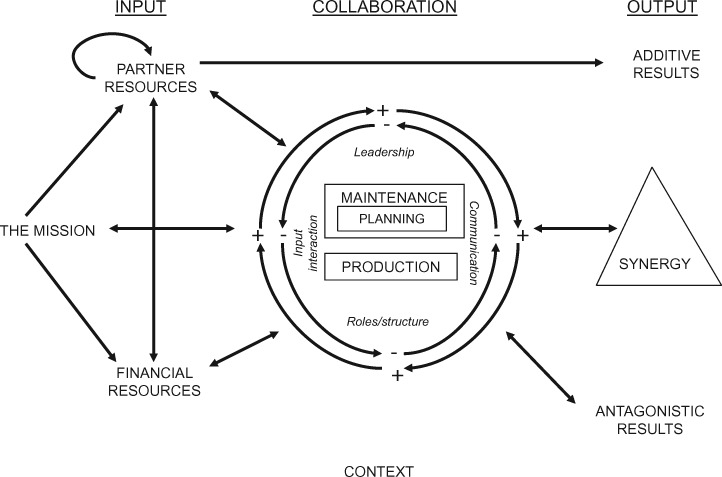

The BMCF depicts the inputs, throughputs and outputs of collaborative functioning as cyclical and interactive processes within the system (see Figure 1). The inputs include: (i) partnership resources; (ii) mission/purpose; and (iii) financial resources, which motivate recruitment of additional inputs according to various dynamics (depicted in the model by arrows). Once the inputs enter the collaboration (throughput area), they interact positively or negatively with elements of the collaborative process such as leadership, communication, roles and structure (or lack thereof), power, trust and funding/partner balance. The outputs of partnership are: (i) additive results (people do what they would have done anyway); (ii) synergy (the sum of the parts is greater than would have been achieved working in isolation); and (iii) antagony (partners achieve less than if they were working on their own). These outputs then feed back into the collaboration, affecting processes of functioning in both negative and positive ways (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008).

Figure 1.

The Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning.

Purpose of review

This scoping review examines the international literature on health promotion partnership processes from 2007 to 2015 and uses the BMCF as a theoretical framework for analyzing the review findings. The review seeks to examine the partnership processes that have been found to contribute to successful partnership functioning and aims to answer the following questions:

What elements, qualities and/or practices are identified as supportive positive processes in partnerships?

What elements, qualities and/or practices are identified as inhibiting partnership functioning or producing negative processes?

The findings from the review help to identify positive and negative partnership processes and “map” what is currently known about developing and sustaining partnerships for health promotion.

Methods

Scoping studies can examine the approaches to research taken for a given topic, assess the value and feasibility of undertaking a full systematic review, summarize existing research findings and draw conclusions about existing gaps in the research literature (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005). This review focuses on the latter two aims. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping studies do not evaluate studies for quality or synthesize findings in terms or relative weight for different designs; instead they map the field of literature existing on a given topic (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010). For this scoping study, we followed the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (Arksey and O’Malley , 2005): (i) defining the research question; (ii) identifying studies; (iii) selecting studies (an iterative process); (iv) charting the data using a descriptive approach; and (v) collating and reporting results.

Based on the research questions stated above, we identified studies by searching the international literature on partnerships for health promotion from January 2007 to June 2015. We conducted an electronic search of databases including CINAHL, ERIC, Medline, PsychINFO, Web of Science and PubMed. We chose search terms that would locate studies examining health promotion partnerships that specifically focused on processes. Therefore, we incorporated relevant synonyms and previously identified partnership processes derived from the BMCF. Searching all database fields, we used the following terms: “health promotion” AND alliances or coalitions or partnership or intersectoral or network or collaboration* AND trust or leadership or roles or communication or “organization* culture” or power AND synergy or antagony or success or failure.

Once we identified the appropriate studies, we applied both practical and methodological criteria to select studies for inclusion (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Fink, 2009). First, the studies had to describe the functioning of intersectoral partnerships and be relevant to the health promotion concept of partnership as described in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO, 1986). To focus in on studies relevant to the WHO HiAP concept of intersectoral partnerships, we excluded studies that described community-based participatory research, focusing only on studies describing partnership between two or more formal organizations collaborating on activities other than research (since this adds an additional level of complication and output). Second, we included only relevant studies that contained detailed information on research methods; we excluded self-authored organization reports. Due to resource limitations, we included only studies published in English. We applied no restrictions on type or quality of study design, and we included quantitative, qualitative and mixed method studies (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010).

The search returned 339 results. After excluding repeated titles, commentaries/editorials/letters and studies that did not cover partnership functioning, we examined 59 studies at the full-text level. We excluded another 33 studies as irrelevant according to the criteria after full-text examination; thus our review includes 26 studies.

We tabulated the included studies, provided a descriptive review of their findings (see Table 1), and then collated and summarized the studies according to an existing analytical framework (Levac et al., 2010)—in this case, the BMCF. The following section presents our findings.

Table 1:

Key findings from the international literature on partnership processes

| Partnership type, country, study author(s) | Study design | Key findings | Dimension of partnership functioning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies | |||

| A network of collaboratives promoting child and family wellbeing. USA (Barile et al., 2012) | An evaluation study exploring collaboration between community partners from multiple settings. The study employed multilevel confirmatory factor analysis of data from a survey completed by 2968 individuals from 157 partnerships. Partnership outputs were examined using the Collaborative Member Survey and the Collaborative Self-Assessment | The findings showed that members’ roles and attendance at meetings predicted more positive individual assessments of communication and leadership, highlighting the need to include multiple perspectives in evaluation. The researchers also found that contextual factors such as SES related to family involvement and population density were related to communication. At the collaborative level, tenure of the leadership predicted overall functioning | Partner resources, communication, leadership, context, maintenance (evaluation) |

| Communities That Care (CTC), USA (Brown et al., 2012) | Survey data from an evaluation of Communities That Care (CTC) over a five year period. Yearly responses varied from 732 in 2010 to 988 in 2007, representing a range of partnerships: 53 in 2010 to 75 in 2005. The study explored partnership benefits and difficulties and employed factor analysis to test two new scales developed in 2010: Participation Benefits and Participation Difficulties. | The study found that participation benefits were significantly associated with coalition attendance and involvement. This is consistent with previous research. The findings also highlighted “coalition directedness” as being enhanced by explicit statements of vision, goals and decision making processes. Strong relationships between partners and effective communication were found to be central to all aspects of functioning and thus difficult to distinguish from other influences. The study focused on functioning rather than explicitly examining output, outcomes or impact. | Partner resources, mission, leadership, roles/procedures, input interaction (partners and other partners) |

| Smoke-free Youth Coalitions and Communities That Care (CTC), USA(Brown et al., 2015) | This study compared collaborative functioning in youth and adult partnerships. Surveys were given to participants in both youth (n = 44) and adult (n = 673) partnerships and the data was examined using multilevel regression analyses | Examining a standardized multidimensional measure of functioning including leadership, task focus, cohesion, costs and benefits of participation, and community support, the findings showed very little variation in the functioning of youth partnerships when compared to adult partnerships. One area of difference identified was increased difficulties in participation for youth which may have important implications. Although the study refers to “outcomes”, the reference is to elements of partnership functioning | Leadership, roles/procedure, input interaction (partners and mission) |

| Families First Edmonton, Canada (Gray et al., 2012) | Four yearly surveys were conducted to evaluate partnership processes in the Families First Edmonton (FFE) project: a multisectoral research effort to develop a model for delivering health and recreation services for low-income families from 2005–2008. The survey incorporated the validated Partnership Self-Assessment Tool (PSAT). The evaluations spanned the formation, implementation and maintenance stages of the project. Longitudinal statistical analyses were applied. Response range varied from the lowest n = 31 in year 1 to n = 44 in year 2 | While this study did not examine population outcomes, it did examine synergy, using the PSAT. The authors found that high levels of synergy accrued during partnership formation but that a significant decrease in synergy occurred during the implementation phase. Explanations included: the addition of new partners which resulted in a loss of consensus on mission and strategy; turnover interrupts momentum and possibly destabilizes the leadership thus increasing vulnerability. Key factors that can contribute to “a rebound in synergy scores” during implementation included: orienting new partners; building a common understanding; authentic integration of new partners’ perspectives, skills and values. Leadership needs to be able to navigate this precarious balance | Mission, partner resources,input interaction (partners and mission), leadership, context |

| Health Promotion Partnerships, Ireland (Jones and Barry, 2011b) | A survey of 337 partners involved in 40 health promotion partnerships in the Republic of Ireland, incorporating a number of multidimensional scales designed to assess the contribution of factors that influence partnership synergy | The most important predictors of synergy (examined as a partnership output) were trust, leadership and efficiency. Synergy centered on trust and leadership. The findings suggest that trust-building mechanisms should be built into the formative stage of partnership and sustained throughout the collaborative process | Leadership, input interaction (trust), maintenance |

| California Healthy Cities and Communities program (CHCC), USA (Kegler et al., 2007) | An evaluation was conducted to identify paths of influence on community capacity. Multilevel analysis was used to illuminate the nature of the relationships between factors. A total of 231 partners from 19 CHCC partnerships completed the survey | Coalition membership indirectly influences community capacity (identified as a partnership outcome) through the processes of leadership, staffing and structure, which then influence member engagement. Broad participation was negatively associated with skill acquisition, implying that large, diverse partnerships may have limited opportunities for individual partners to develop skills. A direct path was identified from task focus to skill acquisition and from cohesion to social capital. The findings suggest modifications to the Community Coalition Action Theory (CCAT) model as applied in this study | Leadership, maintenance, partner resources, synergy feedback |

| California Healthy Cities and Communities program (CHCC), USA (Kegler and Swan, 2012) | Using evaluation data, the study examined pathways and mediating effects of partner engagement on coalition factors and community capacity outcomes. The researchers applied multilevel mediation analyses to surveys completed by 231 partners from 19 CHCC partnerships. The study intended to test the Community Coalition Action Theory (CCAT) regarding capacity building | The results largely supported the CCAT. Membership engagement mediated the effects of both leadership and staffing on community capacity outcomes. Relationships between some process variables were also mediated by member engagement by some direct effects were also observed | Partner resources, leadership, roles/procedures, maintenance |

| Tobacco control agency partnerships, USA (Leischow et al., 2010) | Cross-sectional surveys collected from partners representing 11 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) agencies, and social network analyses were used to examine linkages and to map agencies’ tobacco control communication | The findings suggest that inconsistent communication can hamper the ability of agencies to address tobacco use in a coordinated fashion. A systems approach is recommended to facilitate mutual understanding and improved communication and collaboration between and within agencies. The study examined communication structures but not output, outcomes or impact. | Communication, mission |

| Qualitative studies | |||

| Community partnerships for Cancer Control USA (Breslau et al., 2014) | A qualitative study using grounded theory and content analysis of qualitative interviews with 24 key informants in 6 state-level partnerships (Team-Up) working on evidence-based interventions for low-income women in need of breast cancer screening. Participants were asked about both processes and their perceptions of “success” | The findings indicate different processes influencing different stages of adoption, adaptation and implementation of evidence-based practice. Communication issues and partner turnover inhibited adoption and adaptation. Lack of funding and leadership failure to appropriately engage local stakeholders impeded implementation | Mission, financial resources, communication, leadership, context |

| North–South partnerships with KIWAKKUKI, Women Against AIDS in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania (Corbin et al., 2012) | A case study to explore the process and impact of the scaling up of partnerships for providing services across the spectrum of HIV and AIDS experience, including prevention, education, testing, care and support for families. Data included documents, observation notes and in-depth interviews with six participants. Analysis employed the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning. Participants were asked about processes and their perceptions of positive and negative outputs | Successful partnerships and programs over time created synergy and led to subsequent growth. As this expansion occurred, partnerships and grassroots membership grew. The need for capacity building for volunteers exceeded the financial resources provided by donors (as capacity building was not part of the majority of partners’ missions, although value was placed on grassroots’ involvement). The lack of training negatively impacted the output of the partnership | Partner resources, financial resources, mission, input interaction (partners and mission), maintenance, antagony feedback |

| North–South partnership experience of KIWAKKUKI, Tanzania(Corbin et al., 2013) | A qualitative case study examining North-South partnership from the perspective of a Tanzanian women’s organization working on HIV and AIDS. Open-ended interviews with nine participants. Analysis guided by the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning. Participants were asked about processes and their perceptions of positive and negative outputs | The findings suggest that breakdowns in functioning were not always negative as partners were able to learn from mistakes. The study also found that having substantial partner resources (>6000 grassroots members) balanced the financial contributions of Northern partners and empowered the Southern organization. Multiple funding streams also strengthen the Southern organization’s position as a partner, as did a clear focus on the locally developed organizational mission | Input interaction (distrust), input interaction (power), antagony feedback |

| Latinos in a Network for Cancer Control (LINCC), USA (Corbin et al., 2015) | A qualitative evaluation of a community-academic partnership working to reduce cancer-related health disparities. The analysis employed the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning as the analytic frame to analyze 19 interviews with diverse community and academic partners. . Participants were asked about processes and their perceptions of positive and negative outputs | Sustained partner interaction was found to create “meaningful relationships” which were subsequently called upon for specific partnership initiatives. The findings indicated the need for a dynamic balance between inclusiveness, flexibility and partnership output, with greater inclusiveness of inputs (partners, finances, mission) and loosely defined roles and structure producing strong connections but less network-wide productivity (output). This enabled the creation of more tightly defined and highly productive sub-groups, with clear goals and roles but less inclusive of inputs than the larger network | Input interaction (partners and other partners), roles/procedures |

| Building BeweegKuur Alliances for promotion of physical activity, Netherlands (den Hartog et al., 2014) | An exploratory qualitative study to examine successes and challenges. The data were obtained through four focus groups with regional and local partners and 12 in-depth interviews with alliance coordinators. . Participants were asked about processes and their perception of “results” of the alliance | The findings suggest that flexibility in procedures, leadership and contextual adaptation were important for alliance success. Also using tools to identify positive and negative processes was supportive of success. Finally, the results describe the importance of having adequate time and funding to transcend intersectoral differences, which helped to build trust | Roles/procedures, leadership, context, maintenance (evaluation), input interaction |

| Kentucky Injury Prevention Research Center and four related coalitions, USA (Downey et al., 2008) | A qualitative document analysis examining the developmental stages of partnership working on injury prevention. Outcome data was examined as reported in the documents provided by participating coalitions | The study examined partnership dynamics in the formation of partnerships. Critical components identified include: clear definition of structure, funding, community support, leadership, publicity and data collection and evaluation | Financial resources, roles/procedures, leadership, communication, maintenance (evaluation), context |

| Miami Thrives, USA (Evans et al., 2014) | A qualitative analysis of Miami Thrives incorporating interviews, observational data, network mapping and documents and artifacts to examine the organizational context of 57 organizations to identify processes which support the creation of a partnership for poverty reduction (qualitative perceptions of output and outcomes). | The findings suggest that while it is necessary for the lead organization to create social capital and connections with the community, the organization must have sufficient “intra-organizational” capacity to fulfil its role as a facilitator of partnership. | Partner resources, leadership, context |

| “Eat Smart, Move More” Community Grant Projects, USA (Nelson et al., 2013) | The study examined characteristics of successful partnerships. The data came from 19 semi-structured interviews with county coordinators of community mini-grant projects which were coded according to emerging themes. Based on qualitative descriptions, partnerships were characterized as strong, moderate, or weak. | The study found three overarching themes: continuity (previous connections and a desire for maintaining relationships between partners), community connectedness, and capacity. The success of “strong” partnerships was linked to positive history of partner interaction, partner engagement, clear roles, and a desire for future collaboration. | Input interaction, communication, roles/procedures |

| Smoke Free North East Office: a tobacco control network, UK (Russell et al., 2009) | An ethnographic study of the Smoke Free North East Office coordinating a regional tobacco control network in the UK. Data were collected over a two year period to develop an understanding of the organizational culture and policy contexts in which the staff operates. Data sources included participant-observation, documents, and semi-structured interviews with key partners | Major findings relate to how the office’s ability to act as a “quasi-independent, campaigning organization” enabled them to convene a diverse group of partners under a single umbrella for the purpose of lobbying. A focus on social norm change through social marketing was identified as a pioneering approach. The office was able to provide leadership, accountability and organizational structure | Partner resources, communication, leadership, context |

| Collaborative Policy-making, Canada (Vogel et al., 2010) | A qualitative case study on nutrition labeling policy in Canada incorporating document review and 24 interviews with partners from government, industry, health organizations, professional associations, academia, and consumer advocacy groups. The researchers examined policy adoption as a proximal output and did not examine population level outcomes | The process of policy making was found to be complex, unpredictable and frequently chaotic. Formative progress was hindered by a lack of resources and “policy silos” at the organizational level. A convergence of stakeholder interest was aided by the adoption of a common health promotion issue frame, “champions” within the federal health sector, and collaborative advisory and communication processes | Financial resources, mission input interaction (partners and partners), communication, context |

| Mixed-method studies | |||

| Active Living by Design, USA (Baker et al., 2012) | A mixed method study combining interviews, focus groups, a survey and web-tracking to examine the experience of partners (n = 28) involved in partnerships aimed at changing environments and policies to promote physical activity in 25 communities in the USA | Dynamics of positive functioning were found to include: diverse partners from many sectors; flexible governance structures; group leadership, and action planning. Challenges included difficulty engaging community members and inequitable distribution of financial resources at the local level. Did not examine output, outcomes or impact | Partner resources, financial resources, roles/procedures, leadership, maintenance (planning) |

| Partnership for the Public’s Health (PPH), USA (Cheadle et al., 2008) | A mixed-method evaluation of 39 community and 14 health department partnerships served by Partnership for the Public’s Health (PPH). Data included open-ended interviews with 183 members, 684 surveys over 2 years (from 39 individual partnerships), participant observations and partnership documents | The findings of the overall evaluation confirmed local assessments of factors associated with partnership success. Success was assessed according to five goal (outcome) categories: community and health department capacity building, policy and program development and systems change (leading to population outcomes). Health departments were better able to partner with community groups when they had strong, committed leaders who used creative funding streams, inclusive planning processes, facilitated organizational change and open communication | Financial resources, leadership, roles/procedures, communication |

| Romp and Chomp, Australia (de Groot et al., 2010) | A mixed methods evaluation of the Geelong community obesity prevention project incorporating document analysis, key informant interviews (n = 16), 50% of whom also filled out a quantitative Community Capacity Index survey. Organizational and community capacity building were examined as outcomes of the partnership initiative | Findings highlight the negative impact on functioning of inadequate funding, changing structures, lack of leadership and unclear communication | Financial resources, leadership, roles/procedures, communication |

| Health promotion partnerships, Ireland (Jones and Barry, 2011c) | A mixed methods study utilizing qualitative data from five focus groups to explore the concept of trust in partnerships. Thirty-six partners from health, community, education, arts, sports and youth sectors participated in the focus groups. Based on the data a 14-item trust scale was developed, which was incorporated into a survey on overall partnership functioning | The study developed a new scale to measure partnership trust. The principal component analysis identified two distinct components: trust and mistrust. The study highlighted the importance of measuring perceived levels of trust in partnerships and the need to assess and monitor the impact of both trust and mistrust on partnership functioning. The study examines an element of functioning (trust) and not output, outcomes, or impact | Input interaction (trust), input interaction (distrust), maintenance (evaluation) |

| Health promotion partnerships, Ireland (Jones and Barry, 2011a) | The study was designed to identify how synergy is conceptualized in health promotion partnerships. Five focus groups were organized with 36 health promotion partners. The findings informed the development of a measurement tool, which was tested with 469 partners in 40 health promotion partnerships | An eight-item synergy scale was developed. One component was extracted from the principal component analysis, which accounted for 62% of the variance. The scale, which was shown to be both valid and reliable, constructs synergy as both a partnership process and a product. The scale provides a useful measure for assessing the extent to which partnerships are perceived to be creating synergy. The study examines synergy as an element of functioning as well as an output | Synergy |

| National survey of community-based initiatives developed from qualitative case studies and an expert panel, USA (Lempa et al., 2008) | A mixed-method study using qualitative case studies of eight community partnerships addressing a range of issues including HIV and AIDS, housing, violence, and neighborhood improvement to develop two scales used for a national survey. A total of 291 partnerships were surveyed, n = 702 leaders and members from the USA | The factors represented in the scale were leadership, resources, ability and commitment to organize action, and networking factors. A sixth factor relevant to leaders only was personnel sustainability. The leadership factor contributed to > 5 times the variance of other factors in the factor analysis. The study resulted in a 60-item instrument using factor analysis (44 for leaders, 38 for non-leaders). “Success” was a concept defined qualitatively by interview participants’ own assessment of the partnerships’ effectiveness | Partner resources, financial resources, input interaction (partners and mission), roles and procedures |

| Safe Schools/Health Students, USA (Merrill et al., 2012) | A mixed method evaluation of a national partnership initiative in the US between school districts, mental health, law enforcement, juvenile justice agencies and other community organizations. A survey based on Community Coalition Action Theory was distributed to 1578 partners at 175 sites to collect partner perceptions of the success of the initiative. Qualitative data was also gathered and examined in the course of the evaluation and analyzed using a grounded theory approach | The sites were ranked according to responses from lowest to highest and then perceptions of partnership were connected to performance. Shared decision-making, effective communication and a clear structure facilitated positive perceptions on the part of partners. The results of the study validated the content of the partnership functioning scale (based on CCAT) | Leadership (decision-making), communication, roles/procedures |

| Fighting Back Initative, USA (Zakocs and Guckenburg, 2007) | The study examined factors fostering organizational and community capacity outcomes. Thirteen drug coalitions in 11 states in the USA, n = 217, response rate 63%. Coalition was the unit of analysis. Questionnaires and interviews. The small sample was a limitation and 50% of the coalitions were defunct so were examined retrospectively. Only drug partnerships surveyed | This study found that greater capacity is associated with funding, commitment, participatory decision-making, involvement of local government and collaborative leadership | Financial resources, input interaction (partners and mission), leadership (incl. decision-making) |

Results

The 26 studies included in the review covered diverse partnership arrangements addressing a range of issues including: promoting child and family wellbeing; healthy communities and cities; tobacco control and other substance use prevention initiatives; cancer control; violence prevention; HIV and AIDS prevention and support; nutrition labeling; and programs to increase physical activity. Researchers undertook the majority of these studies in the USA (n = 16), with fewer representing other country settings: Ireland (n = 3), Tanzania (n = 2), Canada (n = 2), the Netherlands (n = 1), Australia (n = 1) and the UK (n = 1). The focus of the partnership studies varied from single case studies to large-scale national surveys. We included studies as long as they described actual functioning of health promotion collaborative arrangements. The studies tended to examine a range of dimensions of partnership within single studies. Of these studies, eight employed mixed method designs, eight were quantitative, and ten were qualitative. Quantitative studies tended to employ multilevel analysis techniques to examine survey data, with two studies examining data over several years. As may be seen in Table 1, sample sizes in the quantitative studies ranged from 200 participants to more than 3000. Qualitative studies, with typically smaller sample sizes, employed grounded theory, ethnographic, document analysis and exploratory designs. This review presents the results according to the main partnership processes identified in the studies, using the framework of the BMCF. Table 1 describes a summary of the study characteristics.

Inputs

Partnership resources

Partner resources encompass resources (other than financial) such as time, skills, expertise, reputation, personal networks and connections, and other relevant characteristics (Corbin, 2006). Participation by diverse, highly skilled partners has been found to predict effectiveness in local public health partnerships (Baker et al., 2012) as long as they share a vision and their goals align. The level of partners’ influence and status also contributes to partnerships, with more influential people being invited into high-level partnerships (Leischow et al., 2010). A study conducted in the US, inquiring into differences in functioning between partnerships with primarily youth members versus adult members, found no significant differences except that youth experienced greater obstacles to participation (Brown et al., 2015).

Studies found that actual partner presence at meetings was crucial for success (Barile et al., 2012). The length of service to the partnership and partners’ previous history with one another was also found to affect functioning in a positive way, as relationships strengthen over time (Nelson et al., 2013; Corbin et al., 2015). Conversely, high partner turnover is associated with negative functioning (Breslau et al., 2014). Research from Tanzania stresses the importance of community involvement, as it ensures the relevance and cultural-appropriateness of services offered (Corbin et al., 2012, 2013). One study from the USA examined the effects of member engagement on coalition processes and outcomes (Kegler and Swan, 2012), finding evidence that partner engagement facilitated community capacity-building outcomes.

“Boundary-spanners” are partners who are able to work across silos, using skills like negotiation and the ability to recognize new opportunities (Jones and Barry, 2011b). Boundary-spanning skills are important in health promotion partnerships because the well-established vertical hierarchies of professional groups can create conflict unless carefully negotiated (Jones and Barry, 2011b).

Mission/purpose

Mission refers to the purpose of a partnership and encompasses the idea of a shared vision and aligned goals. It is widely agreed that partnership mission is an important factor in uniting partners (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008; Corbin et al., 2013; Walden, 2014). One study found that while funders appreciated local community volunteer engagement, they only funded capacity building if it aligned with their own organizational mission (Corbin et al., 2012). Breslau et al. (Breslau et al., 2014) found that partnership processes differed depending upon the mission at different stages (e.g. adoption differed from adaptation and differed still from implementation).

Financial resources

Financial resources include material and monetary contributions. Lempa et al. (Lempa et al., 2008) found that financial resources were considered to be the most important partnership functioning factor by respondents. A lack of funding may lead to an overreliance on volunteers and/or a lack of training, which can negatively impact functioning (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008; Corbin et al., 2012).

Throughputs

Leadership

Leadership characteristics include the ability to promote openness, trust, autonomy and respect (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). Jones and Barry (Jones and Barry, 2011b) and Weiss et al. (Weiss et al., 2002) found an association between leadership and synergy. Research suggests that successful leaders are also able to identify, combine, and distribute financial resources in creative ways (Cheadle et al., 2008; Corbin et al., 2015). While these individual characteristics and skills are clearly important for collaborative leadership, Barile et al. (Barile et al., 2012) also found that the length of time a leader had been in place predicted overall functioning. Furthermore, transparency, inclusiveness, and shared decision making all positively affect partnership functioning (Zakocs and Guckenburg, 2007; Merrill et al., 2012).

Communication

Communication refers to the ways partners (including leadership) convey information both inside and outside the partnership. Kegler et al. (Kegler et al., 2007) found that communication quality was significantly correlated with partner participation, partner satisfaction, successful implementation, good relationships and effectiveness. Participants described face-to-face communication as being more effective than email or telephone (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). Branding of communication—so it is clearly identifiable as part of the partnership—can be important, especially when partners interact on other projects as well (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008; Corbin et al., 2014). Leischow et al. (Leischow et al., 2010) found inconsistency in communication hampered efforts to coordinate partnership. Corbin and Mittelmark (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008) found a lack of consensus among partners on their experience of the appropriate frequency, mode, and characteristics of communication, because individual partners with diverse uses and needs for information subjectively experience communication.

Roles/structure

Roles and structure refer to the level of formalization and specificity within partnerships. Findings vary in the literature in this area. Several studies indicate the importance of role clarification in partnership functioning. Corbin and Mittelmark (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008) reported that vague structures, unclear roles, and nebulous timeframes had a negative impact on productivity. Similarly, Nelson et al. (Nelson et al., 2013) found a positive link between role clarity and successful functioning. However, Gray et al. (Gray et al., 2012) recommend that partnerships have boundaries loose enough to be inclusive but not so loose that their mission is unclear. A recent study found informality in roles, flexibility in funding, and a loosely defined mission enabled the recruitment of many resources but slowed production, while conversely having a more narrow focus increased output but limited participation (Corbin et al., 2014).

Input interaction

Inputs interact in many ways in the context of the collaboration. There is a balance between partner and financial inputs in collaboration, each making up for shortfalls in the other (Corbin et al., 2013). One study found that having adequate partner and financial resources was crucial for building trust across intersectoral boundaries (den Hartog et al., 2014). The term “input interaction” also encompasses the motivational dynamics described above between partners and finances and mission. If partners and/or funders find a mission compelling or aligned with their own, they will be more likely to participate (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008; Vogel et al., 2010; Gray et al., 2012). Lastly, input interaction encompasses the interactions between partners, including power, trust, conflict and friendship (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). In their examination of North–South partnerships, Corbin et al. (Corbin et al., 2013) found that while financial partners often hold ultimate power, a balance can be achieved if partner contributions—such as expertise and community involvement—rival financial contribution in scale, and if there is diversification in funding sources.

Jones and Barry (Jones and Barry, 2011b) found that trust is vital for the creation of synergy and recommend that trust-building mechanisms be built into the partnership-forming stage and sustained throughout the collaborative process.

Maintenance tasks

Maintenance tasks include activities that keep partnerships functioning in practical ways. They do not affect the mission directly but support its achievement by addressing the administrative needs of the partnership, such as grant writing, evaluation, reporting, and communication (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). Jones and Barry (Jones and Barry , 2011b) found that efficiency was a significant predictor of synergy.

Funding affects a partnership’s ability to carry out maintenance activities. Corbin et al. (Corbin et al., 2013) found that inadequate funding for reporting tasks forced partnership staff to work extra hours to make up the shortfall. Another study found that the ability to track and evaluate successes and challenges supported alliance functioning (den Hartog et al., 2014).

Production tasks

Production tasks include any activities that produce results pertaining to the partnership’s mission (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). All of the processes and interactions described above affect a partnership’s ability to produce results—whether synergistic, antagonistic or additive.

Context

Context refers to the external environment within which the partnership exists. It includes the individual contexts of all the partners as well as the economic, political, social, and cultural context (Corbin et al., 2014). One study found that flexible protocols, leadership and the ability to make adaptations according to context supported alliance functioning (den Hartog et al., 2014). Baker et al. (Baker et al., 2012) found that communities with significant economic disparities or those that lacked political capital had greater difficulty “getting things done.”

Organizational context

A study of community–academic partnerships found that the incentives of the academic partners (publications) conflicted at times with the practice-based missions of the community partners (Corbin et al., 2014). Evans et al. (Evans et al., 2014) describe a baseline level of “intraorganizational” capacity that lead organizations must possess in order to engage successfully in a facilitator role within a community partnership. These findings further suggest the utility of conducting action research not only to learn about partnership functioning but also to improve organizational capacity to support the work.

There is evidence that partnerships are not merely at the whim of context but may be in a position to shape it for their own benefit. For instance, Downing (Downing, 2008) identify “publicity” as a critical component of partnership dynamics at the early formational stage. One case study noted the importance of having a “champion” within the federal health sector who helped facilitate the success of the partnership (Vogel et al., 2010). An ethnographic study of a tobacco control partnership in the UK found that the partnership strategy of changing social norms through social marketing supported their work (Russell et al., 2009).

Output

Additive results

Additive results are not impacted by collaboration processes. They describe work that partners accomplish individually without the benefit of collaboration (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). These results are rarely discussed in the literature on partnership functioning but they represent a real risk to collaborations—a loss of the multiplicative value of collaborations if inputs are not adequately engaged (Corbin et al., 2015).

Synergy

Synergy is the intended product of partnership: partners and funders rally around a defined mission to achieve more than would have been possible working in isolation (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008; Jones and Barry, 2011b). Jones and Barry (Jones and Barry, 2011a) found that synergy in health promotion partnerships is both a process and a product of partnership functioning. Gray et al. (Gray et al., 2012), conceptualizing synergy as a product, determined that synergy accrued during the formation stage of partnership and decreased during implementation (impacted by new partners, turnover and/or loss of consensus on mission and strategy).

Several studies using the BMCF have identified not only how synergy is produced in partnerships, but also how it goes on to affect future partnership functioning. For example, Corbin and Mittelmark (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008) found that synergy directly led to the recruitment of additional partners and financial resources. In one partnership, early success led to an increase in the recruitment of resources (Corbin et al., 2012). Less intuitively, perhaps, the study also suggests that growth that happens too quickly can have a negative impact (Corbin et al., 2012).

Not all studies use the term synergy to describe success in partnerships. In Table 1, we have established the ways in which (when appropriate) studies have identified positive outputs, outcomes or impact. Several studies identify community capacity as an important outcome of partnership and seek to understand the pathways of its development (Kegler et al., 2007; Zakocs and Guckenburg, 2007; Cheadle et al., 2008; de Groot et al., 2010; Kegler and Swan, 2012; Merrill et al., 2012). Nelson et al. (Nelson et al., 2013) examined a concept they referred to as “community connectedness” as an outcome. A smaller subset also examined organizational capacity building as an outcome (Zakocs and Guckenburg, 2007; Cheadle et al., 2008; de Groot et al., 2010). A few studies also examined policy impact (Cheadle et al., 2008; Russell et al., 2009; Vogel et al., 2010). Several studies examined a combination of these outputs and outcomes (Zakocs and Guckenburg, 2007; Cheadle et al., 2008; de Groot et al., 2010).

Antagony

Antagony is the term employed by the BMCF to describe negative results (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). Unlike synergy, which gains something through the process of partnership, antagony describes the loss of something along the way—for example, partner time, enthusiasm, trust, financial resources or some other input. Any element of functioning is a potential source of antagony, including negative leadership, poor communication, unclear roles, and mistrust. Every study that has examined partnerships for antagony (including earlier studies not included in this review) found some losses (Endresen, 2007; Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008; Dosbayeva, 2010; Kamau, 2010; Corbin et al., 2013, 2012, 2015; Corwin et al., 2012).

Issues of context can cause antony. In one study of a North–South partnership, funders that did not understand the local context often demanded reporting that was difficult to address and caused burdensome maintenance activities for Southern staff, drawing scarce resources away from mission-driven activities (Corbin et al., 2013).

Synergy and antagony exist simultaneously within partnerships (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). Success or failure is not indicated by their complete absence or presence but by a balance in one direction or the other. This balance can be perceived differently by different partners; one partner can think things are going well while another partner feels they are failing in their goal (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008; Corbin et al., 2015).

An important finding related to antagony comes from Corbin et al. (Corbin et al., 2013), who documented the ability of partnerships to learn from negative experiences to improve future functioning. This points to the need for ongoing partnership evaluation so that learning can take place (Downey et al., 2008; Evans et al., 2014).

DISCUSSION

The findings of this scoping review build on previous reviews (Koelen et al., 2008; Fawcett et al., 2010) by mapping the current research on the elements of partnership functioning that contribute to successful intersectoral partnerships for health promotion. This review indicates that there are a number of core partnership processes, as outlined in the results, identified across the studies as contributing to successful partnership functioning. However, few of the studies comprehensively assessed the nature of these processes, the key factors influencing their development, and how they interact in the context of different types of partnerships. There is also a paucity of research studies examining the combined effect of partnership processes and how they impact partnership outcomes. We cannot conclude, for example, that certain types of partnerships are more likely to include processes that are critical to producing synergistic outcomes. This is not surprising, as it is methodologically quite complex and challenging to capture the dynamic nature of partnership processes and how they are interrelated in the context of different types of partnerships. The relative impact of different partnership processes and their dimensions, therefore, remains unclear.

The BMCF, as a theoretical model, does attempt to capture the multidimensional and interactive nature of partnership functioning, in terms of how different inputs interact to produce different outputs. However, there is a need for further empirical study to provide a more in-depth insight into how the various partnership processes develop, interact, and influence each other in leading to a greater probability of positive outcomes. It is unclear from this review, for example, whether different types of intersectoral partnerships may give rise to different forms of partnership structure or management, which will in turn result in different types of leadership, communication, and trust building. There is a need for more systematic empirical studies of the different dimensions and processes of partnership functioning and how they interact to produce positive processes and outcomes. In this respect, researchers could also draw on the broader public management literature exploring collaborative networks, where similar observations have been made regarding the need for more holistic and multidimensional models of network effectiveness. Reviews of the public management literature on collaborative network effectiveness, which also includes partnerships, have highlighted the different types of network characteristics such as structural, managerial, contextual, and process variables, as well as their interaction in the context of different types of networks in influencing overall network performance effectiveness (Young and Ansell, 2003; Parent and Harvey, 2009; Turrini et al., 2010). It is clear that many of these characteristics and variables are also highly relevant for health promotion partnerships (e.g. how different governance mechanisms will influence leadership, power sharing, decision making, trust, etc.). These variables could be tested empirically to determine their relative influence on partnership effectiveness. Future studies need to incorporate both process-oriented and objective outcome-focused measures in their evaluations of partnership effectiveness.

While the overall review analysis highlights gaps in the health promotion literature, there are a number of findings that can be used to optimize intersectoral partnerships in implementing a HiAP approach.

We used the BMCF (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008) to guide our presentation of the review’s findings. The elements and processes depicted in the model covered the majority of findings described in the reviewed studies. However, the model does not explicitly describe some elements, namely the specific delineation of certain key partner interactions such as trust and power sharing (Jones and Barry, 2016). Also, we have presented community involvement as a type of “partner resource,” but the definition of community requires further consideration and operationalization. We have also grouped “boundary-spanners” into “partner resources,” but this may not adequately describe their role within the partnership, since partner resources are an input and boundary-spanning is a process.

A major limitation of the existing literature is that out of the 26 studies examined in this scoping review, there was little consistency in the methods used to examine functioning alongside outputs and outcomes. Clearly, identifying partnership processes that lead to effective partnership outcomes necessitates more comprehensive evaluation studies that will examine both the process and outcomes of partnerships to determine which processes are the most critical to achieving positive outcomes. Such research will increase our ability to draw conclusions about how partnership processes influence outcomes. Toward this end, the BMCF could be extended to examine how synergy as an output is related to specific partnership outcomes such as those suggested by the studies included in this review (e.g. enhanced community capacity, organizational capacity, policy development, and systems change) (Kegler et al., 2007; Cheadle et al., 2008; Lempa et al., 2008; Kegler and Swan, 2012).

LIMITATIONS

The diversity of partnership studies examined in this review makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions. The variability in the studies’ quality—including the study designs, the range of sample sizes, measures used, and levels of partnerships examined (single, multiple, local, regional, national, international/inter-country)—limits our ability to make comparisons.

The review is further limited because it includes only studies published in English, excluding important research conducted in other languages. Given this language bias, the paper examines studies primarily from North America, Ireland, the UK, and Australia, with only two exceptions: Netherlands and Tanzania. This limitation means we are unable to judge whether the elements and practices of collaboration in English-speaking countries hold true in other international contexts.

Relying on journal databases further limits the representation of studies. This may skew the findings toward positive partnership processes, since manuscripts presenting negative findings are less likely to be published or reported. A comprehensive search of the grey literature was not conducted due to resource limitations of the research team. While acknowledging these limitations, a number of useful insights regarding processes that impact partnership functioning can be gleaned from the reviewed studies.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

This scoping review has identified a number of core processes in developing intersectoral partnerships for health promotion. It is important to remember, however, that partnership is a system—there is no “correct” way to do it. While there can be weaknesses in certain areas, the partnership can still succeed in the end; it requires an understanding of how to compensate in other parts of the system. With this in mind, we identify the following recommendations for practice based on the findings from this review:

Mission: develop a shared vision, align goals to the partners’ individual or institutional goals, and be mindful of the mission and its ability to attract financial resources.

Resources: include a broad range of participation from diverse partners, including community members. Ensure a balance between human and financial resources.

Leadership: Partnership leadership can take many different shapes: single leaders, co-leaders, or teams of leaders. The specifics are not as important as the ability of those leaders to inspire trust, instill confidence, be inclusive of diverse partners (especially community members), and be collaborative and transparent in the decision-making process. Regular attention should be paid to how the leadership is perceived and to whether or not the current style of leadership is working, so adjustments can be made if necessary.

Communication: Appropriate frequency, mode, and style of communication can be highly variable in different partnerships. Regular monitoring of how partners perceive communication will generate important information about how to adjust for optimal functioning.

Roles/structure: A balance can be observed between loose structure and inclusiveness of inputs and tight structure and production of output. At different times, partnerships may wish to expand recruitment of partners and funding by defining their goals and roles more broadly. At other times, they may seek to narrow their focus to produce specific results. Role clarification promotes accountability and leads to increased output (typically synergy).

Input interaction: Attention should be paid to the balance of partner resources and financial resources. A lack of funding may be compensated for by voluntary partner contributions but may eventually lead to burnout. A lack of partners may be redressed by paying people to participate but may hamper sustainability. Power that comes from contributing significant financial resources can be balanced by recruiting greater numbers of partner resources. These dynamics may serve different purposes for different partnerships, but any particular strategy should be entered into with a solid understanding of the possible negative ramifications. Trust is vital for the creation of synergy, and the findings suggest that trust-building mechanisms should be built into the partnership from the beginning and maintained for its duration. Shared power is another key element of partnership functioning and is particularly relevant to multi-sectoral health promotion partnerships. Partners can represent several different sectors including health and civil society, which already experience power imbalances. Power in partnerships must include the power to define problems and propose solutions.

Maintenance and production tasks: Partner and financial resources are finite. Partners are either working on maintenance activities or production activities. It is important to ensure that the balance is appropriate, as too much time spent on maintenance can result in less production work to achieve the partnership’s mission. In contrast, too little time spent on maintenance activities can cripple the partnership’s ability to function and thus impede its ability to achieve its mission.

Context: Context affects each part of the partnership system. The political, economic, cultural, social and organisational contexts determine what mission/purpose will need to be addressed, the partners and funding available, and the relationships between those inputs. Context also affects the throughput portion of the system by affecting power relations, degrees of formality, modes and customs of communication, and other elements of functioning. In terms of output, the context influences its creation, as described above, but the output is also the point at which the partnership can affect the context.

Evaluation of additive results, synergyand antagony: Monitoring and evaluation emerged as a crucial activity for partnerships. The review findings highlight the need to assess how the partnership is functioning at different stages of its development, to communicate successes, to anticipate upcoming issues, and to learn from and respond to existing problems.

CONCLUSION

Despite the widespread use of intersectoral partnership in health promotion, there is limited empirical study of the effectiveness of different types of partnerships. There is a need for further research to include both process-oriented and outcome-focused measures in order to determine which processes are critical to achieving synergistic positive outcomes. The studies reviewed in this paper highlight the complexity of how partnerships function in real-life settings. While all partnerships, and the diverse contexts within which they take place, have unique features and idiosyncrasies, it is clear that some processes are observed consistently across partnerships. The BMCF provides a useful framework for examining the process of partnership work. The review findings suggest that additional tools need to be developed to drill down into assessing particular processes, and that research from other fields, such as public management, could guide this work. The model could be improved to support the simultaneous examination of processes and outcomes by extending beyond outputs to also examine outcomes such as enhanced community and/or organizational capacity, policy development, systems change, and population health improvements resulting from the partnerships. Such research is needed to begin to understand what specific processes most impact intersectoral partnership functioning and lead to positive outcomes and long-term success.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Professor Maurice B. Mittelmark, University of Bergen, Norway for his contribution to the early stages of developing this review paper. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their feedback which we feel improves the utility of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Amaral-Sabadini M., Anderson P., Braddick F., Corbin H., Farke W., Gual A., Ysa T. (2012) Alice Rap WP 21, MS 36 Evaluation Report 1 http://www.alicerap.eu/ (last accessed 20 July 2016).

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aveling E.-L., Jovchelovitch S. (2014) Partnerships as knowledge encounters: a psychosocial theory of partnerships for health and community development. Journal of Health Psychology, 19, 34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker E. A., Wilkerson R., Brennan L. K. (2012) Identifying the role of community partnerships in creating change to support active living. American Journal Of Preventive Medicine, 43, S290–S299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barile J. P., Darnell A. J., Erickson S. W., Weaver S. R. (2012) Multilevel measurement of dimensions of collaborative functioning in a network of collaboratives that promote child and family well-being. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49, 270–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau E. S., Weiss E. S., Williams A., Burness A., Kepka D. (2014) The implementation road: engaging community partnerships in evidence-based cancer control interventions. Health Promotion Practice, 16, 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L. D., Redelfs A. H., Taylor T. J., Messer R. L. (2015) Comparing the functioning of youth and adult partnerships for health promotion. American Journal Of Community Psychology, 56, 25–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss F. D., Kegler M. (2009) Toward a comprehensive understanding of community coalitions: moving from practice to theory In DiClemente R. J., Crosby R. A., Kegler M. (eds), Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research, 2 edition.Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 157–193. [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle A., Hsu C., Schwartz P. M., Pearson D., Greenwald H. P., Beery W. L., Casey M. C. (2008) Involving local health departments in community health partnerships: evaluation results from the partnership for the public’s health initiative. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 85, 162–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. H. (2006). Interactive processes in global partnership: a case study of the global programme for health promotion effectiveness. IUHPE Report Series. http://www.webcitation.org/5wlpFpPl6 (last accessed 20 July 2016).

- Corbin, J. H., Fernandez, M. E., and Mullen, P. D. (2014). Evaluation of a community–academic partnership lessons from latinos in a network for cancer control. Health Promotion Practice, 16, 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Corbin J. H., Fisher E. A., Bull T. (2012) The international union for health promotion and education (IUHPE) student and early career network (ISECN): a case illustrating three strategies for maximizing synergy in professional collaboration. Global Health Promotion, 19, 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. H., Mittelmark M. B. (2008) Partnership lessons from the global programme for health promotion effectiveness: a case study. Health Promotion International, 23, 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. H., Mittelmark M. B., Lie G. T. (2012) Scaling-up and rooting-down: a case study of North-South partnerships for health from Tanzania. Global Health Action, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. H., Mittelmark M. B., Lie G. T. (2013) Mapping synergy and antagony in North–South partnerships for health: a case study of the Tanzanian women’s NGO KIWAKKUKI. Health Promotion International, 28, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. H., Mittelmark M. B., Lie G. T. (2015) Grassroots volunteers in context: rewarding and adverse experiences of local women working on HIV and AIDS in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Global Health Promotion, 23, 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin L., Corbin J. H., Mittelmark M. B. (2012) Producing synergy in collaborations: a successful hospital innovation. The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, 1717, Article 5. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot F. P., Robertson N. M., Swinburn B. A., de Silva-Sanigorski A. M. (2010) Increasing community capacity to prevent childhood obesity: challenges, lessons learned and results from the Romp & Chomp intervention. BMC Public Health, 10, 522–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hartog F., Wagemakers A., Vaandrager L., van Dijk M., Koelen M. A. (2014) Alliances in the Dutch BeweegKuur lifestyle intervention. Health Education Journal, 73, 576–587. [Google Scholar]

- Dosbayeva K. (2010) Donor-NGO collaboration functioning: case study of Kazakhstani NGO [Master’s thesis]. Retrieved February 25, 2011, from https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/4450 (last accessed 20 July 2016).

- Downey L. M., Ireson C. L., Slavova S., McKee G. (2008). Defining elements of success: a critical pathway of coalition development. Health Promotion Practice, 9, 130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing J. (2008). The conception of the Nankya model of palliative care development in Africa. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 14, 459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endresen E. M. (2007) A case study of NGO collaboration in the Norwegian Alcohol Policy Arena [Master thesis]. Retrieved February 25, 2011, from https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/4466 (last accessed 20 July 2016).

- Evans S. D., Rosen A. D., Kesten S. M., Moore W. (2014) Miami Thrives: weaving a poverty reduction coalition. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53, 357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett S., Abeykoon P., Arora M., Dobe M., Galloway-Gilliam L., Liburd L., Munodawafa D. (2010) Constructing an action agenda for community empowerment at the 7th Global Conference on Health Promotion in Nairobi. Global Health Promotion, 17, 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink A. (2009) Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper, 3rd edition Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gray E., Mayan M., Lo S., Jhangri G., Wilson D. (2012) A 4-year sequential assessment of the Families First Edmonton partnership: challenges to synergy in the implementation stage. Health Promotion Practice, 13, 272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugstad A. (2011) Promoting public health in Norway: A case study of NGO–public sector partnership using the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning University of Bergen, Norway. https://bora.uib.no/bitstream/1956/5292/1/Master %20thesis_Haugstad.pdf (last accessed 20 July 2016).

- Jones J., Barry M. M. (2011a) Developing a scale to measure synergy in health promotion partnerships. Global Health Promotion, 18, 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J., Barry M. M. (2011b) Exploring the relationship between synergy and partnership functioning factors in health promotion partnerships. Health Promotion International, 26, 408–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J., Barry M. M. (2016) Factors influencing trust and mistrust in health promotion partnerships. Global Health Promotion. DOI: 10.1177/1757975916656364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamau A. N. (2010). Documentation of the Implementation strategy. A case study for the Kibwezi Community-Based Health Management Information System project, Kenya [Master’s thesis]. Retrieved February 25, 2011, from https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/4276 (last accessed 20 July 2016).

- Kegler M. C., Norton B. L., Aronson R. (2007) Skill improvement among coalition members in the California Healthy Cities and Communities Program. Health Education Research, 22, 450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler M. C., Swan D. W. (2012) Advancing coalition theory: the effect of coalition factors on community capacity mediated by member engagement. Health Education Research, 27, 572–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelen M. A., Vaandrager L., Wagemakers A. (2008) What is needed for coordinated action for health? Family Practice, 25, i25–i31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelen M. A., Vaandrager L., Wagemakers A. (2012) The Healthy ALLiances (HALL) framework: prerequisites for success. Family Practice, 29, i132–i138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker, Weiss E. S., Miller R. (2001) Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Quarterly, 79, 179–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leischow S. J., Luke D. A., Mueller N., Harris J. K., Ponder P., Marcus S., Clark P. I. (2010) Mapping U.S. government tobacco control leadership: networked for success? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12, 888–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lempa M., Goodman R. M., Rice J., Becker A. B. (2008) Development of scales measuring the capacity of community-based initiatives. Health Education & Behavior, 35, 298–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucidarme S., Marlier M., Cardon G., De Bourdeaudhuij I., Willem A. (2014) Critical success factors for physical activity promotion through community partnerships. International Journal of Public Health, 59, 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill M. L., Taylor N. L., Martin A. J., Maxim L. A., D’Ambrosio R., Gabriel R. M., Wells M. E. (2012) A mixed-method exploration of functioning in safe schools/healthy students partnerships. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35, 280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J. D., Moore J. B., Blake C., Morris S. F., Kolbe M. (2013) Characteristics of successful community partnerships to promote physical activity among young people, North Carolina, 2010–2012. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10, E208–E208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent M. M., Harvey J. (2009) Towards a management model for sport and physical activity community-based partnerships. European Sport Management Quarterly, 9, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Roussos S. T., Fawcett S. B. (2000) A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annual Review of Public Health, 21, 369–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell A., Heckler S., White M., Sengupta S., Chappel D., Hunter D. J., Lewis S. (2009) The evolution of a UK regional tobacco control office in its early years: social contexts and policy dynamics. Health Promotion International, 24, 262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrini A., Cristofoli D., Frosini F., Nasi G. (2010) Networking literature about determinants of network effectiveness. Public Administration, 88, 528–550. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel E., Burt S., Church J. (2010) Case study on nutrition labelling: policy-making in Canada. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice & Research, 71, 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden J. (2014) A Qualitative Study of Collaboration between Principals, Teachers and the Parents of Children with special needs. https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/8211 (last accessed 20 July 2016).

- Weiss E. S., Anderson R. M., Lasker R. D. (2002) Making the most of collaboration: exploring the relationship between partnership synergy and partnership functioning. Health Education & Behavior, 29, 683–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (1986) WHO | The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/ (last accessed 20 July 2016).

- WHO. (1988) WHO | Adelaide Recommendations on Healthy Public Policy. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/adelaide/en/index.html (last accessed 5 November 2015). [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2013). The Helsinki Statement on Health in All Policies, pp. i17–i18. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/8gchp/en/ (last accessed 5 November 2015). [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2014). WHO | Health in All Policies: Framework for Country Action. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/frameworkforcountryaction/en/ (last accessed 5 November 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Young L., Ansell N. (2003) Young AIDS migrants in Southern Africa: policy implications for empowering children. AIDS Care, 15, 337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]