Abstract

Given the growth of interdisciplinary and community-engaged health promotion research, it has become increasingly common to conduct studies in diverse teams. While there is literature to guide collaborative research proposal development, data collection and analysis, little has been written about writing peer-reviewed publications collaboratively in teams. This gap is particularly important for junior researchers who lead articles involving diverse and community-engaged co-authors. The purpose of this article is to present a series of considerations to guide novice researchers in writing for peer-reviewed publication with diverse teams. The following considerations are addressed: justifying the value of peer-reviewed publication with non-academic partners; establishing co-author roles that respect expertise and interest; clarifying the message and audience; using the article outline as a form of engagement; knowledge translation within and beyond the academy; and multiple strategies for generating and reviewing drafts. Community-engaged research often involves collaboration with communities that have long suffered a history of colonial and extractive research practices. Authentic engagement of these partners can be supported through research practices, including manuscript development, that are transparent and that honour the voices of all team members. Ensuring meaningful participation and diverse perspectives is key to transforming research relationships and sharing new insights into seemingly intractable health problems.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, collaboration, knowledge transfer, action research, methodology

INTRODUCTION

Raphael has argued that community participation and inclusion are fundamental principles of health promotion and social change movements (Raphael, 2000). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) practices have come a long way towards democratizing research (Minkler and Wallerstein, 2003; Viswanathan et al., 2004; Israel et al., 2006). CBPR often involves collaboration with communities that have long suffered a history of colonial and extractive research practices (Smith 1999; Simpson 2001; Casale et al., 2011).

Health promotion research teams engaged in health equity work often include multiple non-academic partners (Flicker et al., 2008). Team members outside the academy can include policy makers, staff at community-based organizations and/or community representatives. “Peer researchers” is a term that has been coined to describe members of the community under-study that are trained and supported to become research team members (Logie et al., 2012; Guta et al., 2013). For some of these folks, particularly those who may have had limited access to formal secondary education, publishing for peer reviewed journals may feel like an overwhelming and alienating task.

Authentic engagement of these partners can be supported through research practices, including manuscript development, that honour the voices of all team members. Making time and space for meaningful participation and diverse perspectives is key to transforming research relationships and developing new insights into seemingly intractable health problems (Minkler, 2005). However, few explicit guidelines exist for how to succinctly write about this work in peer-reviewed journals using approaches that honour the principles of collaboration (Bordeaux et al., 2007; McNiff and Whitehead, 2009; Flicker, 2014; Herr and Anderson, 2014).

The purpose of this article is to present a series of considerations related to collaboratively developing health promotion manuscripts for peer-reviewed publication with diverse stakeholders. Our intended audience includes junior scholars, graduate students and their community partners who may be new to preparing manuscripts. The insights in this article were generated and refined through workshops that we have lead on this topic with research teams and new scholars in Canada and South Africa. What sets this article apart from other excellent resources on the topic of manuscript preparation is an explicit focus on how to write for publication collaboratively in teams.

This article is a companion to an earlier publication introducing a participatory approach to qualitative analysis (Flicker and Nixon, 2014). Whereas the collaborative DEPICT method was developed to explicate practical steps for engaging diverse team members in qualitative analysis, this article offers guidance for writing collaboratively for academic journals. In published manuscripts, the sophisticated work of collaboration is usually invisible. This article transparently shares approaches to collaborative manuscript development in an effort to catalyze deeper reflection on strategies of inclusion during the writing process and why it matters for health promotion. In particular, the following considerations are addressed: justifying the value of peer-reviewed publication with non-academic partners; establishing co-author roles that respect expertise and interest; clarifying the message and audience; using the article outline as a form of engagement; knowledge translation within and beyond the academy; and multiple strategies for generating and reviewing drafts.

JUSTIFYING THE VALUE OF PEER-REVIEWED PUBLICATION WITH NON-ACADEMIC CO-AUTHORS

Diverse health promotion research teams will frequently include community-based partners whose input will strengthen an article, yet who may not initially view this form of knowledge translation as worthy of their limited time. As such, a first consideration is to ensure that all research team members, including non-academics, appreciate the value and purpose of peer-reviewed publication for meeting a study’s goals.

Some partners, particularly those from marginalized communities, may struggle to see the utility of the endeavour and even resent the process. Community partners have told us that they believe that peer-reviewed publications are largely inaccessible documents that serve dominant, colonial interests. They have argued that working on this form of writing usurps valuable time and resources that could be more meaningfully spent doing frontline support, advocacy work or more accessible forms of knowledge translation. Tuck et al. (Tuck et al., 2008) add another consideration: for those who have been systematically silenced and taught that their own voice in unworthy, writing can be painful. These valid critiques need to be carefully considered.

In one particular case, a community-based partner shared that she had experienced backlash from her past participation in publication efforts. She explained that she had lost considerable trust from fellow community members and that her (and her organization’s) reputation suffered because others publicly attacked her for ‘selling out’ and participating in ‘the academic industrial complex.’ This example reminds us that there are real and diverse risks to participation in publishing efforts. Some academics, particularly those who are tenured, may be relatively insulated from on-the-ground implications that may be most seriously experienced by community partner authors when research findings are controversial.

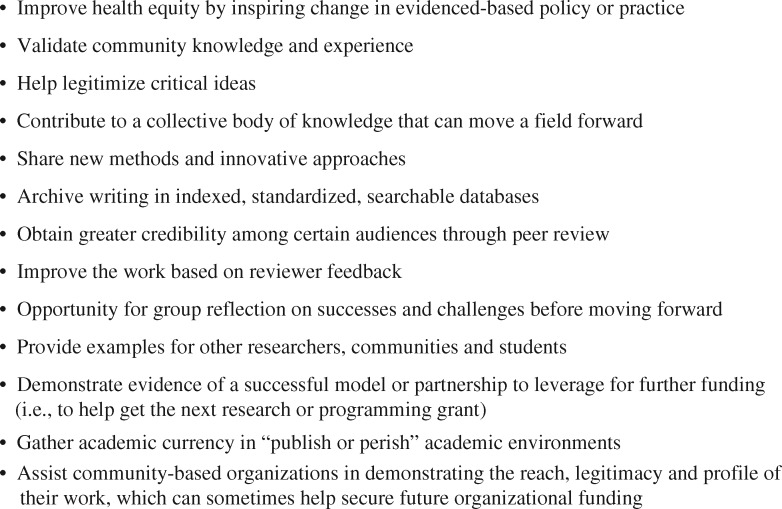

Facilitating an open and honest dialogue about the value and potential impacts of manuscript development early in a team project can build trust and help ensure that the needs of all partners are acknowledged and met. It may be useful to discuss the potential risks alongside the value of sharing stories in peer-reviewed publications, such as advancing advocacy efforts, lending credibility to critical ideas, introducing innovative approaches to research, and moving a field forward (Bordeaux et al., 2007). Figure 1 presents a list of potential reasons why teams might choose to publish in peer-review journals.

Fig. 1:

Reasons why research teams may wish to share their work in peer-reviewed journals.

For those based in academic environments (i.e. students and professors), Van der Meulen (Van der Meulen, 2011) argues that publication in peer-reviewed journals is often a career imperative. Publications may also have instrumental value to the team in pursuing future grants to continue a larger programme of research or fund further intervention work. It is important for teams to surface and openly discuss what individual team members might need to do to achieve their personal and professional goals.

Situating peer reviewed journals as part of larger comprehensive knowledge translation and exchange plan can be a useful starting place (Armstrong et al., 2006; Graham et al., 2006; Nixon et al., 2013). CBPR teams often develop an array of dissemination products to share research results (e.g. videos, websites, social and traditional media campaigns; see, for example the work of Flicker et al., 2010).

In some cases, legitimate concerns about the limited accessibility of peer-reviewed publications for non-academic audiences can be mitigated. For instance, teams can commit to publishing only in open-access journals in order to make articles equally available to those within and outside of universities. Alternatively, teams can also commit to using accessible language and/or to writing community-friendly summaries of all manuscripts that are publicly available. In other cases, teams may agree to the sequence of always writing community-friendly products before moving on to academic outputs. Alternatively, academics might take the lead on journal articles while community members concurrently lead other, more accessible outputs. Increasingly journals are also expanding their visions of acceptable formats; for instance some now welcome arts-based submissions. At the same time, new peer-reviewed venues for publication, such as http://ces4health.info/ are available for disseminating health research-related outputs that are not in traditional journal formats.

Once consensus is established around the purpose, value and place manuscripts can play in a knowledge translation strategy, spending some time mapping possible articles can be useful for clarifying key arguments and ensuring that no single manuscript tries to take on too much. This approach also helps limit overlap between articles. Forchuk and Meier (Forchuk and Meier 2014) suggest that creating an “article idea chart” can help research teams keep track of different potential papers. Ideally, the chart tracks manuscript topics, authoring teams (since not all team members need to be co-authors on each manuscript), target, key deadlines for submission or presentation at conferences, and progress status. The chart can become a living document that is shared and regularly revisited by the team to help ensure progress and accountability. New technological innovations that allow for synchronous (and asynchronous) sharing and editing documents (e.g. google docs or dropbox) can facilitate the process of having a larger team share ownership of the planning (and later writing).

ESTABLISHING CO-AUTHOR ROLES THAT RESPECT UNIQUE EXPERTISE, AVAILABILITY AND INTEREST

On large team projects, it may not be possible (or desirable) for all team members to participate on every paper. As a group, team members may wish to choose which writing teams they prefer to join. Each team needs a lead or co-leads responsible for ushering a paper towards publication. Each writing team should clarify roles and responsibilities of various contributors that take into account people’s strengths, experience, availability and interest. Then, they can make a plan for who, will do what, by when, and how each member will be credited. As others have argued, the scope of individual contributions should be established and order of authorship negotiated before major work begins (Albert and Wager, 2004; Kalpakjian and Meade, 2008). Order of authorship often means much more to some team members than to others (e.g. those in the early stages of their academic career). Authorship order may also need to be revisited as the work progresses to ensure it reflects shifting contributions.

According to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, authorship is based on the following four criteria: “(1) Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work; (2) Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) Final approval of the version to be published; and (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved” (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, 2015). They argue that all four criteria must be met to qualify for authorship. In an effort to increase transparency about relative involvement, some journals now request detailed information about each author’s contribution.

Another consideration is that authorship is not always just about putting pen to paper; it should acknowledge the depth and quality of ideas contributed. It may be important for research projects that have tried to maintain equitable community–university partnerships throughout, to find a way to maintain that balance during manuscript development. For example, Flicker once partnered with a program that served HIV-positive youth on a research project. The coordinator, who at the time had little interest in, or time to devote to, academic publications, was nevertheless a key intellectual contributor to overall project design and implementation. While he did not contribute to drafting the manuscripts, his ideas, actions and work were so central to the project that he was encouraged to join authorship teams. As the process unfolded, he provided valuable oral feedback and direction. Indeed, manuscripts were deeply enriched by his contributions. The collaborative process allowed him to see the potential value and impact of academic publication, and he later returned to school to pursue an undergraduate degree. A decade later, he is now pursuing a PhD.

Castleden et al. (Castleden et al., 2010) have noted that one persistent challenge with community-based research is that standardized publication guidelines do not regularly “account for cultural differences as to what constitutes an intellectual contribution, particularly when contributions are oral, not written.” One strategy that they have adopted is crediting an entire community as authors to honour community-level investment and contributions. This is particularly salient in Indigenous communities that have community-wide decision-making structures in place (e.g. a research committee, see for example, Castleden et al., 2008). Similarly, others have credited community-based agencies, advisory boards or research teams. In work with communities with a history of research violence (i.e. where past research has violated human rights or been used as a rationale to uphold oppressive colonial practices) extra caution is merited. As Van der Meulen (Van der Meulen, 2011) argues, “issues of intellectual property and copyright legislation as well as questions of authority and ownership over the research results are particularly important and should be resolved well in advance of the study.”

A different strategy is to consciously create capacity-building opportunities, as well as human and financial resources, for supporting community members and trainees to actively participate in manuscript development in order to meet conventional guidelines. Many of our students come from the communities with whom we partner. This presents a unique opportunity to closely mentor them in collaborative writing to become ‘first authors.’ In fact, the University of Toronto, where Nixon is based, actively rewards its faculty for this form of mentorship by equating the contribution of “senior responsible author” with being a “principal author” on publications.

CLARIFYING THE MESSAGE AND THE AUDIENCE

Before the manuscript writing begins in earnest, there is value in achieving consensus within a diverse team on three strategic questions: (1) What is the main message of this article? (2) What was found that is significant, worth sharing and may advance the field? And (3) Who is the intended audience?

Various authors recommend that a strategy for achieving clarity is distilling the essence of results into one or more tables, figures, diagrams or sketches (Harley et al., 2004; Bordeaux et al., 2007; Marshall and Brennan, 2008). In quantitative research, this approach often means generating tables, models or figures. In qualitative and mixed-method work, this approach may involve the creation of schematics to illustrate results. Other approaches include making tables of quotes by theme, or identifying metaphors to convey complex ideas in the research results. While these graphic depictions of results may not be included in the final article, this process can facilitate writing teams to crystallize their thoughts regarding the core message in their findings. This is also an opportunity to draw on diverse talents in the team, noting that some members might be more visually inclined and have novel ideas for how to (re)present information.

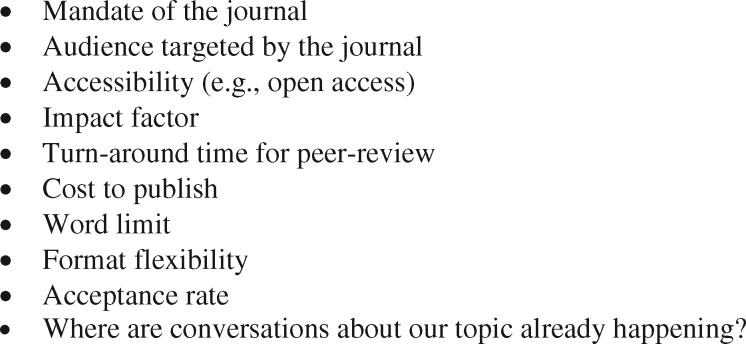

Equally important at this phase is consensus on the audience that the study team wishes to target with this main message. For example, Nixon’s research falls at the intersection of the fields of health equity, rehabilitation science, and HIV. She and her teams regularly make strategic choices about the aspects of study findings that they will intentionally target for certain disciplinary journals in order to reach health equity, rehabilitation or HIV audiences. Clarifying the audience supports not only the approach to argumentation in the manuscript, but also the selection of a journal for submission (Marshall and Brennan, 2008). Authorship teams may wish to identify a first and second choice journal for submission, ensuring they share a similar audience and word limit in order to promote efficient resubmission if not initially successful (Harley et al., 2004). In choosing target journals, it is useful to consider a variety of factors (see Figure 2). One may also investigate the extent to which preferred journals have published in the topic area in order to proactively engage in this thread of the academic conversation when developing the manuscript. Furthermore, writing teams may find value in identifying articles published in the target journal that are similar in methodological style to the approach in their manuscript. Reviewing the structure and argumentation of these concrete samples as a team can support diverse members to better appreciate the end-product.

Fig. 2:

Considerations in choosing a journal.

Finally, a pragmatic technique well known to experienced writers is to comprehensively review the journal’s instructions for authors at this early stage. Marshall and Brennan (Marshall and Brennan, 2008) highlight how reviewing and writing according to these guidelines can save teams editing time later in the process. Furthermore, Kurmis (Kurmis, 2003) argues that this approach also ensures that key messages are properly tailored to their intended audience. Sharing and discussing these strategies with the entire authorship team helps to demystify the process and offers everyone a chance to feedback into the process.

CREATING AN ARTICLE OUTLINE AS A FORM OF ENGAGEMENT

A key challenge of writing manuscripts with diverse teams is ensuring the ongoing meaningful and appropriate engagement of all team members in the process. One strategy for addressing this challenge is to use the process of creating the article outline as a form of collective engagement.

Creating a point-form outline, before drafting an entire paper, can help ensure that all team members support and are afforded an opportunity to contribute to the arguments put forward. An article outline can also help to make sure that the paper is focused, the argument is cohesive and ideas are organized (Kalpakjian and Meade, 2008). During this process, all the necessary points are included, but extraneous ideas are ruthlessly excluded. The aim is to arrive at an outline comprising only the ideas that are essential to the core argument (Marshall and Brennan, 2008).

When working with youth, Flicker has used the idea of ‘story boarding’ to create an outline with a group. Using index cards and sticky notes with drawings or key themes and ideas, she has worked with teams to literally move around, collate and distill ideas until a coherent narrative outline emerges.

According to Kalpakjian and Meade (Kalpakjian and Meade, 2008), attending to this conceptual work and paying close attention to detail has the potential to save time down the road. Another added bonus of circulating and discussing an outline is the time commitment necessary to review and provide feedback, which is relatively small compared to reviewing a full draft.

Reviewing the outline may be an opportune time to facilitate dialogue about the discussion section of a paper. Whereas there may be limited room for creativity in presenting empirical data, the discussion section requires substantial innovative and applied thinking. This is the section where community-engaged authors often excel because they sometimes see the implications for policy and practice first.

A colleague, Sarah Switzer, takes this innovation a step further with her youth collaborators. Using plastic microphones and boas as props, youth peer researchers “interview” each other about the meaning and implications of project results. The summary graphics that are collectively created to stimulate discussion are used to stimulate innovative interpretations of their data. Transcripts of these “interviews” are then workshopped to build the foundation of the results and discussion sections. In this way, she is able to draw on youth voices and language to add authenticity to their collective writing and crystalize her outline.

KNOWLEDGE TRANSLATION WITHIN AND BEYOND THE ACADEMY TO STRENGTHEN ARGUMENTATION

While the goal may be to share and legitimize results through publication in a peer-reviewed journal, diverse teams have unique opportunities to strengthen the article’s argumentation because of their access to multiple audiences. That is, the conceptual clarity and rigour of the article’s core argument can be matured, strengthened and evolved by attempting to convey this message to different audiences and by different team members. Specifically, teams may wish to have various members pilot test the article’s emerging arguments at conferences, and other knowledge translation fora.

Actively presenting preliminary work serves multiple purposes. First, these commitments can generate movement and momentum and nurture enthusiasm within a team to propel it to the finish line (i.e. submission of a polished manuscript for publication). Second, presenting in multiple fora to different types of audiences enhances the reach of the dissemination process. Third, it is also an opportunity to fine-tune arguments and seek valuable feedback from those in attendance. In addition, having different team members present the paper means that they will each have an opportunity to think through and articulate ideas about the manuscript in their own words, which can help inform the written discussion and other sections. Finally, for those team members who may be gifted at oral communication (rather than writing), public presentations offer the opportunity to gather their wisdom in ways that work to their strengths. In our experience, “gems” often emerge from team members when they are speaking off the cuff to audiences. These interpretations can later be incorporated into the writing phase. One further tactic is to audio-record presentations and use the transcripts as the backbone for a first draft.

Nixon has used this strategy in her research on the experiences of people living long-term with HIV in Zambia. Specifically, her team organized separate workshops with Zambian study participants and healthcare workers to discuss the team’s findings. The community-based Zambian fieldworker led the discussion with participants who asked many nuanced questions and identified gaps in the analysis. Because of the trust built between the fieldworker and the community, the ensuing conversation was so informative that it helped the team revise its analysis and craft a stronger final paper.

MULTIPLE STRATEGIES FOR GENERATING AND REVIEWING DRAFTS

It is noteworthy that the preceding considerations take place before a full draft of an article is written. This sequence may be counterintuitive to scholars whose experience is working independently. We argue that the process of collaboratively writing a manuscript for publication with a diverse and community-engaged team necessarily involves considerations that are different from writing alone. This does not imply, however, that there is only one right way to develop a full manuscript as a team. On the contrary, there are multiple approaches that can promote inclusion and participation of team members.

Often, a paper’s lead author(s) takes the collective wisdom generated by the group away and those most skilled at the task at hand write a first draft. In an ideal scenario, they will have ample material generated by the group in the form of graphics, summary tables, a solid outline, notes from team meetings and/or recordings from conference presentations. Feedback is then solicited and incorporated over multiple cycles.

Another common model when working with graduate students or other academic colleagues is to delegate sections for different team members to write, and then uniting them to generate a first draft. This only works if team members have the motivation and time to achieve these tasks. Ritchie and Rigano (Ritchie and Rigano, 2007) propose an alternative model of having two or more people literally sit together at a keyboard and writing the paper together. This approach may be an excellent capacity building strategy, but can be very time-consuming. Alternatively, another colleague, Dr. Robb Travers, has experimented with setting up a table with multiple laptops, each featuring different sections of a manuscript. Each member of the writing team rotates through the different sections until a manuscript emerges from collating all the sections.

Sitting down to write can sometimes be an uncomfortable moment for lead authors who have been deeply committed to collaborative practices up until this point. Finding the right tone and balance that honours diverse viewpoints and styles of communication with professional expectations dictated by journal editors can be challenging. Tuck et al. (Tuck et al., 2008) have argued that it can sometimes be particularly tricky to attribute key ideas to one or more authors when a paper is written in a collective voice. Using non-traditional processes for capturing the thoughts of community partners (e.g. tape recording or journal entries) and displaying diverse insights within the manuscript (e.g. oscillating between I/we, a rebuttal to comments made by academic partners, or an epilogue describing the action steps emerging from a project) are useful strategies for working through some of these tensions (Bordeaux et al., 2007).

Once a first draft is compiled, it needs to get circulated to the larger writing team for feedback and discussion. At this stage, some teams prefer to only see drafts that are near completion. Other teams will want to see a rougher version that leaves lots of room for feedback. Teams will need to figure out the right balance that works for them.

Often, several drafts will be shared before a final version is deemed ready for submission. On some teams, authors can go through the manuscript on their own to track changes/suggestions and then return their comments to the paper’s lead, whose job will be to incorporate all the feedback. On other teams, it may be useful to schedule meetings or conference calls to facilitate conversations that fine-tune the manuscript. On projects where co-authors may experience literacy challenges, it can be useful to read drafts out loud and invite conversation. In some cases, drafts may also need to be submitted to organizational or community structures for review prior to submission for peer-review. All listed co-authors should have an opportunity to review the final draft and agree that is represents their viewpoints before it is submitted.

One or more team members may wish to re-review journal guidelines and ensure the manuscript adheres to specifications. Careful attention to grammar (Kurmis, 2003), spelling, brevity and concision are important factors to consider when writing for publication (Kurmis, 2003; Marshall and Brennan, 2008).

Subsequent revisions and responses to reviewers will also need to be recirculated. As Wang et al. (Wang et al., 1998) have argued, full participation of every member of the authorship team in all aspects of each stage is neither necessary nor desirable. Rather, welcoming participation (in the ways that each partner feels good about), but not forcing it, can be a more successful tactic.

CHALLENGES AND CELEBRATIONS: FURTHER THOUGHTS ON MANUSCRIPT DEVELOPMENT

Whereas the steps above focus on unique aspects of writing in a team, lessons for collectives can also be drawn from experiences of writing alone. Finding the right amount and type of time to write for publication is a common challenge. Some writers find that blocks of uninterrupted time (within a day or, ideally, over a period of days) are best for the work of writing. Others advise writing at least a small portion every day to stay close to a writing project. Some find writing retreats (Kiewra, 1994; Murray and Newton, 2009) or writing groups (Haas, 2011) to be motivating and useful sites of social and technical support. These groups can also be spaces to model and support various strategies for collaboration. Most importantly, recognize that writing takes time and explore strategies to find the best fit personal circumstances and style.

Reading both within and beyond one’s field, exposes writers to a range of writing styles from which to take inspiration (or caution). One strategy to becoming a better writer is to subscribe to an open-access journal and to read at least one article in each issue. Another is to become a reviewer. Reviews can be formal for peer-reviewed journals. For more junior team members, reviews can be conducted as part of a journal club or informally for colleagues. Tremendous insight can be developed through scrutinizing the writing of another.

The process of developing a manuscript for publication is typically long and frequently thankless. It can be particularly demoralizing when a paper is rejected or reviewer comments are cruel, biting or off the mark. The process can sometimes drain rather than energize teams. Celebrating successes at each stage of the writing process can help to build morale (Kalpakjian and Meade, 2008). The form of celebration can shift according to the nature of the team (e.g. from a celebrationary team email to gathering for a meal), but the symbolic value of marking each stage of achievement should not be missed. The obvious points for celebration are upon formal submission to a journal, and upon eventual publication, but teams may wish to identify other relevant moments or “firsts” in which to honour the good work of their collectives.

CONCLUSION

Minkler and Wallerstein (Minkler and Wallerstein, 2003) and Flicker et al. (Flicker et al., 2008) have argued that inclusion and participation are central philosophical tenets of a CBPR approach. Writing is fundamentally a social and political act. The kinds of questions we ask and answer, as health promotion researchers, have the power to shape the ways in which the world is seen, understood and reproduced. Writing can reify, reinforce and/or challenge power inequalities. It can also be a catalyst for change. Stoecker (Stoecker, 2009) has eloquently written about how in community-based research, writing ought to be a means to an action end, and the paths we take to get there ought to follow our emancipatory intentions.

Writing together is neither easy nor without its challenges. Power imbalances often come to the fore and sometimes important voices are silenced in the rush to the finish (Savan et al., 2009). Nevertheless, writing collaboratively has the potential to honour the participation and intellectual contributions of diverse team members (Castleden et al., 2010), increase productivity (Mayrath 2008) and enrich the quality of our scholarship (Flicker and Nixon, 2014). Some find it enjoyable; others may feel that being held accountable to a group can be motivating.

The aim of this article is to inspire teams conducting community-engaged research to reflect on their practices for publishing their work, and to promote dialogue on how we might train a new generation of health promotion scholars to write together and with others. Taking the time and energy to “do it right” and ensure that diverse voices get heard, can also be conceived of as a form of activism. By meaningfully engaging diverse (often community-based) team members in this act typically reserved for academics, we bolster the argument that these voices, and these forms of expertise, matter and need to be heard.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank: all the anonymous reviewers, Sarah Switzer, and Drs. Zack Marshall, Adrian Guta and Ciann Wilson for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript, Renée Monchalin for her research assistance and David Flicker for his copy editing help.

FUNDING

Dr. Stephanie Nixon is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award (#494142).

REFERENCES

- Albert T., Wager E. (2004) How to handle authorship disputes: a guide for new researchers The Committee on Publication of Ethics (COPE) Report 2003 White C., Journalist F.. London, UK: BMJ Books; 2004, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong R., Waters E., Roberts H., Oliver S., Popay J. (2006) The role and theoretical evolution of knowledge translation and exchange in public health. Journal of Public Health, 28, 384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordeaux B. C., Wiley C., Tandon S. D., Horowitz C. R., Brown P. B., Bass E. B. (2007) Guidelines for writing manuscripts about community-based participatory research for peer-reviewed journals. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 1, 281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale M. A., Flicker S., Nixon S. A. (2011) Fieldwork challenges lessons learned from a North–South Public Health Research Partnership. Health Promotion Practice, 12, 734–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castleden H., Garvin T., First Nation H.-a.-a. (2008). Modifying photovoice for community-based participatory indigenous research. Social Science & Medicine, 66, 1393–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castleden H., Morgan V. S., Neimanis A. (2010) Researchers' perspectives on collective/community co-authorship in community-based participatory indigenous research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics: An International Journal, 5, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S. (2014) Disseminating Action Research. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Action Research, vol. 1, Coghlan D., Brydon-Miller M.. SAGE, London: pp. 276–280. [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S., Nixon S. (2014) The DEPICT model for participatory qualitative health promotion research analysis piloted in Canada, Zambia and South Africa. Health Promotion International 30, 616–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S., Savan B., Mildenberger M., Kolenda B. (2008) A snapshot of community based research in Canada: who? what? why? how? Health Education Research, 23, 106–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S., Travers R., Flynn S., Larkin J., Guta A., Salehi R., Pole J. D., Layne C. (2010) Sexual health research for and with urban youth: the Toronto Teen Survey story. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 19, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Forchuk C., Meier A. (2014) The article idea chart: a participatory action research tool to aid involvement in dissemination. Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, 7, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Graham I. D., Logan J., Harrison M. B., Straus S. E., Tetroe J., Caswell W., Robinson N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26, 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guta A., Flicker S., Roche B. (2013). Governing through community allegiance: a qualitative examination of peer research in community-based participatory research. Critical Public Health, 23, 432–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas S. (2011). A writer development group for master’s students: procedures and benefits. Journal of Academic writing, 1, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Harley C. D., Hixon M. A., Levin L. A. (2004) Scientific writing and publishing—a guide for students. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, 85, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Herr K., Anderson G. L. (2014) The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty, Sage Publications, London. [Google Scholar]

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. (2015) Defining the role of authors and contributors. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html (last checked 8/11/2015).

- Israel B., Eng E., Schultz A., Parker E. (2006) Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass, Berkeley, CA [Google Scholar]

- Kalpakjian C. Z., Meade M. (2008) Writing manuscripts for peer review: your guide to not annoying reviewers and increasing your chances of success. Sexuality and Disability, 26, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Kiewra K. A. (1994) A slice of advice. Educational Researcher,: 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kurmis A. (2003) Contributing to research: the basic elements of a scientific manuscript. Radiography, 9, 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Logie C., James L., Tharao W., Loutfy M. R. (2012) Opportunities, ethical challenges, and lessons learned from working with peer research assistants in a multi-method HIV community-based research study in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 7, 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall G., Brennan P. (2008) From MSc dissertations to quantitative research papers in leading journals: a practical guide. Radiography, 14, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrath M. C. (2008) Attributions of productive authors in educational psychology journals. Educational Psychology Review, 20, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- McNiff J., Whitehead J. (2009) Doing and Writing Action Research, Sage Publications, London. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. (2005) Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. Journal of Urban Health, 82, ii3–ii12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M., Wallerstein N. (2003) Community-Based Participatory Research for Health., Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Murray R., Newton M. (2009) Writing retreat as structured intervention: margin or mainstream? Higher Education Research & Development, 28, 541–553. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon S. A., Casale M., Flicker S., Rogan M. (2013) Applying the principles of knowledge translation and exchange to inform dissemination of HIV survey results to adolescent participants in South Africa. Health Promotion International, 28, 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael D. (2000) The question of evidence in health promotion. Health Promotion International, 15, 355–367. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie S. M., Rigano D. L. (2007) Writing together metaphorically and bodily side-by-side: an inquiry into collaborative academic writing. Reflective Practice, 8, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Savan B., Flicker S., Kolenda B., Mildenberger M. (2009) How to facilitate (or discourage) community-based research: recommendations based on a Canadian survey. Local Environment, 14, 783–796. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. (2001) Aboriginal peoples and knowledge: decolonizing our processes. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 21, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Smith L. T. (1999) Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. , St. Martin's Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Stoecker R. (2009). Are we talking the walk of community-based research? Action Research, 7, 385–404. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck E., Allen J., Bacha M., Morales A., Quinter S., Thompson J., Tuck M. (2008) PAR praxes for now and future change: the collective of researchers on educational disappointment and desire. In Cammarota J., Fine M.(Eds.), Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 49–83. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meulen E. (2011) Participatory and action-oriented dissertations: the challenges and importance of community-engaged graduate research. The Qualitative Report, 16, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M., Ammerman A., Eng E., Gartlehner G., Lohr K., Griffith D., Rhodes S., Samuel-Hodege C., Maty S., Lux L.. et al. (2004) Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Summary, evidence report/technology assessment, No 99. Rockville, MD, RTI-University of North Carolina Evidence Based Practice Center & Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang C., Yi W., Tao Z., Carovano K. (1998) Photovoice as a participatory health promotion strategy. Health Promotion International, 13, 75–86. [Google Scholar]