Abstract

As recreational marijuana expands, it is critical to develop standardized surveillance measures to study the retail environment. To this end, our research team developed and piloted a tool assessing recreational marijuana retailers in a convenience sample of 20 Denver retailers in 2016. The tool assesses: (i) compliance and security (e.g. age-of-sale signage, ID checks, security cameras); (ii) marketing (i.e. promotions, product availability and price) and (iii) contextual and neighborhood features (i.e. retailer type, facilities nearby). Most shops (90.0%) indicated the minimum age requirement, all verified age. All shops posted interior ads (M = 2.6/retailer, SD = 3.4), primarily to promote edibles and other non-smoked products. Price promotions were common in shops (73.7%), 57.9% used social media promotions and 31.6% had take-away materials (e.g. menus, party promotions). Nearly half of the shops (42.1%) advertised health claims. All shops offered bud, joints, honey oil, tinctures, kief, beverages, edibles and topicals; fewer sold clones and seeds. Six shops (31.6%) sold shop-branded apparel and/or paraphernalia. Prices for bud varied within and between stores ($20–$45/‘eighth’, ∼3.5 g). Twelve were recreational only, and eight were both recreational and medicinal. Liquor stores were commonly proximal. Reliability assessments with larger, representative samples are needed to create a standardized marijuana retail surveillance tool.

Introduction

Since 2012, eight states and the District of Columbia legalized adult recreational marijuana use. Additionally, 29 states have medical marijuana use and/or decriminalization laws [1]. A majority of the US adults favor such measures [2]; thus, additional states are likely to adopt similar legislation, despite ongoing debate regarding its health effects [3–9].

The emerging marijuana retail environment lacks standardized measures for systematic monitoring of industry marketing practices, particularly for the retail environment. Such measures have been essential in documenting the impact of retail marketing for tobacco and alcohol and informing regulation [10–12]. To date, limited research has focused on the marketing practices of marijuana retailers [13], which is concerning during this pivotal period in its emergence. Such research is critical, as the tobacco literature indicates that advertising attracts new users [11, 14–17], expands markets [11, 16, 18, 19], promotes continued use [18, 20, 21], and builds brand loyalty [19]. The majority of existing research on marijuana marketing has focused on online marketing [22, 23] rather than brick-and-mortar retail. In addition, understanding the community (e.g. proximity to other retailer types) and store environment (e.g. interior marketing) may help contextualize marketing strategies [24] and identify high-risk target populations [13].

Drawing from the tobacco and alcohol literature [11, 16, 18, 19, 25, 26], the goal of this preliminary research was to develop and pilot test a marketing surveillance tool for marijuana retailers. This research was informed by the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) State and Community Tobacco Control (SCTC) Research Initiative to support the dissemination and implementation of rigorous tobacco retail surveillance. A Steering Committee of SCTC investigators developed the Standardized Tobacco Assessment for Retail Settings (STARS) survey and training materials in 2013–2014 to inform state and local tobacco control policy efforts [27]. This study aims to emulate this prior work by conducting formative research to extend such efforts to address surveillance of marijuana retail.

Methods

Pilot site

Denver was chosen as the study site because Colorado was the first state to legalize recreational marijuana and has more than 100 recreational retailers [28]. Colorado laws require: (i) licensing (e.g. retailers must possess a recreational license but can apply for a medicinal license); (ii) age-of-sales restrictions (i.e. mandatory age verification, prohibition of marijuana sales to customers under 21 unless medicinal); (iii) limits on operating hours (i.e. 8 a.m. to mid-night [29]); (iv) advertising restrictions (e.g. prohibition of outdoor advertising [29]); and (v) packaging (e.g. mandatory child-resistant containers, packaging with warning statements and Colorado’s Universal Symbol indicating marijuana content [30]). State law allows further local governmental regulation [29]. Colorado also has a public health campaign called ‘Good to Know’, which is designed to educate consumers about marijuana laws and health effects [31].

Development of the marijuana retail surveillance tool

The five authors developed the marijuana retail surveillance tool (MRST) based on measures from instruments selected based on content relevance and reliability [27, 32–34]. Specifically, we adapted measures from: (i) a premise survey previously used to characterize >1000 medical marijuana dispensaries in California [32]; and (ii) the vape shop module of the Standardized Tobacco Assessment for Retail Settings (V-STARS) [33, 34]. The V-STARS was chosen because vape shops demonstrate similarities to marijuana retailers that are irrelevant to other tobacco retailers [i.e. vape shops are devoted to the sale of electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) vaporizers, liquids and paraphernalia]. A list of product offerings was informed by a review of the literature (e.g. [22, 35]). Assessments of promotional strategies were based on existing literature regarding strategies used on marijuana retailer websites (e.g. [22]).

Data collection

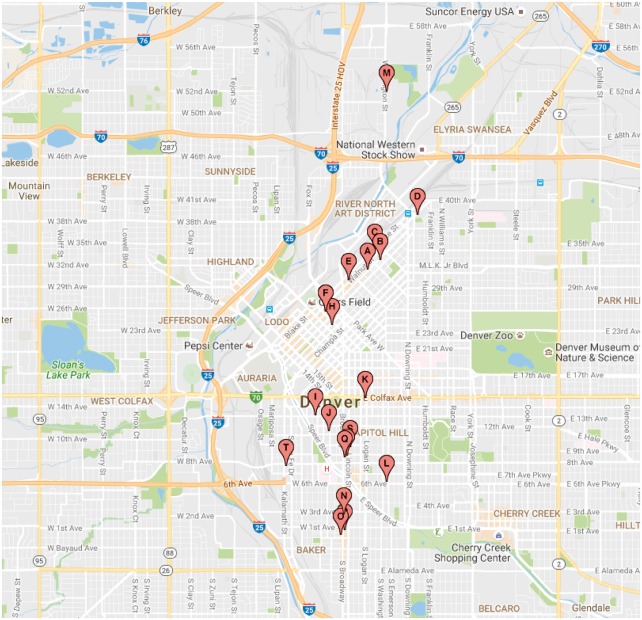

In September 2016, the first author visited a convenience sample of 20 downtown Denver retailers, derived from Weedmaps (www.weedmaps, com), a website for locating retail sources and online forums for users to discuss products/dispensaries (Fig. 1). Data were collected using paper-and-pencil, guided by the MRST and recommended procedures [36].

Fig. 1.

Map of marijuana retailers in the pilot sample. https://batchgeo.com.

Compliance and security

Presence of five variables were coded: exterior signage indicating minimum age requirement or minors not allowed, ID checks, exterior security cameras, security personnel outside and security personnel in waiting room.

Marketing

Variables were coded into three broad categories: promotion, product availability, and price. Regarding promotion, the number of ads, defined as professionally printed and branded signs, were counted separately for exterior and interior. The type of product advertised was also coded. Price promotions were counted and categorized according to the following categories: early bird (i.e. during morning hours) or happy hour specials (i.e. those occurring later in the day); daily or weekly specials; retailer loyalty programs; and other (if any, describe). In addition, we coded if there were any social media promotions (if any, describe); types of take away materials (if any, describe); number of health warnings including any signage or printed materials indicating potential health risks (if any, describe); and number of health claims including any signage or printed materials indicating any potential health benefits (if any, describe). Product availability included: bud (loose or pre-packaged); joints or pre-rolled marijuana; honey oil (hash oil or concentrates used to make shatter or wax); tinctures (alcohol-based cannabis extracts usually applied under the tongue); kief (resin glands which contain the terpenes and cannabinoids that make cannabis); beverages (e.g. sodas); edibles (e.g. gummies, truffles, cookies); topicals (e.g. lotions, lip balms; applied transdermally); clones (cloned marijuana plants); seeds (seeds to grow a new plant); other marijuana product (write in); glassware (e.g. bowls, waterpipes); vaporizers; rolling papers; branded apparel (e.g. t-shirts, hats); branded paraphernalia (e.g. glassware); and other non-marijuana product (open-ended description). Price was recorded as the highest and lowest price per unit (per serving [≤10 mg of THC] or per eighth [3.5 g] for bud) for each marijuana product category.

Contextual and neighborhood characteristics

The observer coded whether the shop was recreational only or both recreational and medicinal, per Weedmaps and signage. Photographs were taken when possible/allowed. Finally, the observer walked/drove around each retailer covering two blocks in each direction to document other nearby facilities (e.g. liquor stores, smoke shops), using validated methods with high reliability [37, 38].

Completing the MRST assessment took an average of ∼20 min. After all assessments were completed, websites of each shop were examined to verify whether the retailer also sold medical marijuana and to compare with data collected on site, including product availability and price ranges across categories per unit. Few differences between point-of-sale assessments and online assessments were documented and thus not presented.

Data analysis

Given the study’s exploratory nature and small sample size, descriptive statistics were conducted, using SPSS 23.0. Of the 20 retailers, one was not open during its posted times and was excluded from analyses requiring interior observations.

Results

Compliance and security

Almost all shops (90.0%) had exterior signage indicating the minimum age requirement and/or that minors were not allowed (Table I). All shops had personnel verifying age by requesting to see customers’ identification. All retailers had exterior security cameras.

Table I.

Marijuana retailer characteristics, n = 20

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Compliance and security | |

| Age verification | |

| Indicating age requirement; minors not allowed | 18 (90.0) |

| ID check personnel inside | 20 (100.0) |

| Security | |

| Security cameras | 20 (100.0) |

| Security personnel outside door | 5 (25.0) |

| Security personnel in waiting room (% of n = 12)a | 2 (16.7) |

| Marketing—promotion | |

| Ads | |

| Exterior product ads | 0 (0.00) |

| Interior product adsa | 19 (100.00) |

| Average ads per retailer (M, SD)a | 2.6 (3.4) |

| Types of products on ads (of 49 ads) | |

| Bud | 6 (12.2) |

| Edibles | 23 (46.9) |

| Beverages | 8 (16.3) |

| Topicals | 8 (16.3) |

| Other | 4 (8.1) |

| Any price promotions/discountsa | 14 (73.7) |

| Types of promotionsa | |

| Early bird/happy hour specials | 3 (15.8) |

| Daily/weekly deals | 8 (42.1) |

| Loyalty club memberships | 5 (26.3) |

| Other | 3 (15.8) |

| Social media promotionsa | 11 (57.9) |

| Take away materialsa | 6 (31.6) |

| Health warnings and claimsa | |

| Had Colorado’s ‘good to know’ cards available | 8 (42.1) |

| Health claims made/suggested | 8 (42.1) |

| Contextual and neighborhood characteristics | |

| Type of retailer | |

| Recreational only | 12 (60.0) |

| Recreational and medical | 8 (40.0) |

| Other facilities within two blocks | |

| Liquor stores | 20 (100.0) |

| Smoke shops | 9 (45.0) |

| Bars/clubs | 17 (85.0) |

| Restaurants | 19 (95.0) |

Of 19 retailers open at time of assessment.

Marketing

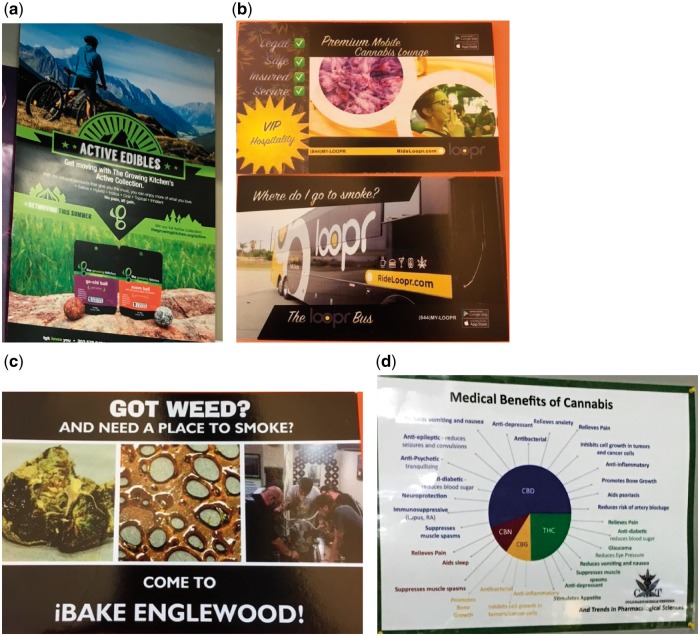

No shops had exterior ads for marijuana, but all of them had interior ads. In total, there were 49 interior ads (M = 2.6, SD = 3.4; Table I), with the greatest proportion promoting edibles (46.9%; Fig. 2a). Price promotions and discounts were recorded in 73.7% of the shops. The most common were daily/weekly deals (42.1%). Additionally, 57.9% of shops used social media (per signage, take-away materials or television screens). Six shops had take-away materials (e.g. menus; signs/stickers promoting brands, discounts or the shop itself). Cards/flyers promoting private parties where marijuana use would be social and legal were also available (Fig. 2b and c).

Fig. 2.

Purchase packaging and promotional materials from retail shops. (a) Sample edible ad. (b) Party bus promotion. (c) Private party promotion. (d) Sample health claims promotion.

Notably, 42.1% of shops displayed any health warnings. The only warning documented across retailers was Colorado’s ‘Good to Know’ card highlighting potential health effects. At least as many shops (42.1%) advertised some reference to marijuana’s health benefits, particularly related to topicals (Fig. 2d); 62.5% of medical/recreational dispensaries vs. 37.5% of recreational-only dispensaries referenced any health benefits.

All retailers offered bud, joints/pre-rolled, honey oil, tinctures, keif, beverages, edibles, topicals, glassware, vaporizers and rolling papers (not shown in tables). Only one shop sold clones and seeds, respectively. Six shops (31.6%) sold shop-branded apparel and/or paraphernalia. Pricing for edibles, beverages and topicals were quite similar across shops (∼$6–8/serving; $20–24/eight to ten servings). However, the price ranges for bud were highly variable, with the lowest documented price ranging from $20–45/eighth.

Contextual and neighborhood characteristics

More shops were recreational only (n = 12) than both recreational and medicinal (n = 8). Neighborhood systematic observations found that liquor stores were within two blocks of all 20 marijuana shops. Bars/clubs, restaurants and smoke shops were also common (Table I).

Discussion

This study was a first step in developing a surveillance tool for assessing the marketing practices and sociocontextual characteristics of recreational and/or medical marijuana retailers. While this study is limited by its focus on a convenience sample of 20 retailers chosen from Weedmaps in one city, the use of a single auditor and limited scope in assessment, subsequent research will test inter-rater reliability, examine the utility of the instrument across multiple settings, and identify specific variables relevant to both recreational and medical establishments.

In the current study, the marijuana retail shops were highly compliant in indicating the age requirement to enter and in verifying age. Moreover, there were security measures at each shop, which is critical in preventing criminal activity [39].

In terms of promotion, novel products (e.g. edibles, topicals) were most frequently advertised, likely in an attempt to familiarize customers with newer products, as bud is still among the most popular products sold [40]. In Colorado, first quarter retail sales of marijuana concentrates in 2016 surged 125%, and sales of edibles increased by 53% from the same period in 2015 [40]. These trends exceeded the 11% rise in sales for marijuana bud, indicating the success of marketing for alternative products [40]. Additionally, daily/weekly deals, loyalty club memberships and early bird/happy hour specials were prevalent. These types of promotional tactics are more common to on-premise alcohol outlets (i.e. bars/clubs that serve alcohol) than to off-premise tobacco and alcohol outlets (i.e. stores that sell these products to be consumed off-premise). The marijuana industry may be attempting to build strong brand affiliation with shops rather than products [41–43]. Social media and take away materials were also common. Notably, the promotion of ‘private’ parties may blur the line between public versus private marijuana use within a policy context where public use is prohibited. In addition, health benefits of marijuana, particularly topicals, were depicted in signage and take away materials. However, such signage was more common in the shops that also had a medicinal license.

With the exceptions of seeds and clones, all retailers in our sample sold marijuana in a variety of non-traditional forms. Although there was variability in products within and between stores, the MRST did not count the number of products within each category. The price ranges for most products also did not vary greatly, with the exception of bud. This lack of variability in product offerings and price suggests that other shop characteristics (e.g. promotional strategies, branding) might be used to differentiate retailers from one another.

Finally, many retailers were proximal to liquor stores, as documented previously [44], and many were close to smoke shops, which is concerning given the high rates of marijuana-tobacco co-use [45, 46]. Contextual features of marijuana retailers should be examined in relation to their marketing practices in future research with larger samples across more diverse contexts, as prior research has suggested that these marketing practices differ by context [24] and may indicate target populations [13].

Conclusions

This study represents the first step in developing a rigorous tool for understanding the neighborhood characteristics of recreational marijuana retailers and assessing their marketing and point-of-sale practices. Future research will validate the tool across contexts and examine its reliability. Tools such as this will facilitate research regarding the impact of point-of-sale marketing on marijuana use and on how sociocontextual differences impact retail marketing.

Funding

National Cancer Institute (1R01CA179422-01; PI: Berg; National Cancer Institute's State & Community Tobacco Control Initiative (U01-CA154281; MPI: Henriksen, Luke, Ribisl); and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA032715; PI: Freisthler). The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.National Conference of State Legislatures. State Medical Marijuana Laws May 23, 2016. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx. Accessed: 14 November 2017.

- 2. Pew Research Center. Majority Now Supports Legalizing Marijuana Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2013. Available at: http://www.people-press.org/2013/04/04/majority-now-supports-legalizing-marijuana/. Accessed: 14 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hall W. What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction 2015; 110: 19–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hall W, Degenhardt L.. The adverse health effects of chronic cannabis use. Drug Test Anal 2014; 6: 39–45.http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dta.1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collins C. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thompson GR 3rd, Tuscano JM.. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 878–9.http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1407928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM.. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2219–27.http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1402309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Volkow ND, Compton WM, Weiss SR.. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 879.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wolff V, Rouyer O, Geny B.. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 878..http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1407928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shi Y, Meseck K, Jankowska MM.. Availability of medical and recreational marijuana stores and neighborhood characteristics in Colorado. J Addict 2016; 2016: 7193740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF.. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; CD003439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Point-of-purchase alcohol marketing and promotion by store type—United States, 2000–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52: 310–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graves SM. Cannabis city: medical marijuana landscapes in Los Angeles. Cal Geogr 2011; 51: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen X, Cruz TB, Schuster DV. et al. Receptivity to protobacco media and its impact on cigarette smoking among ethnic minority youth in California. J Health Commun 2002; 7: 95–111.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730290087987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evans N, Farkas A, Gilpin E. et al. Influence of tobacco marketing and exposure to smokers on adolescent susceptibility to smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995; 87: 1538–45.http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/87.20.1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanewinkel R, Isensee B, Sargent JD. et al. Cigarette advertising and adolescent smoking. Am J Prev Med 2010; 38: 359–66.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paynter J, Edwards R.. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 2009; 11: 25–35.http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntn002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilpin EA, White MM, Messer K. et al. Receptivity to tobacco advertising and promotions among young adolescents as a predictor of established smoking in young adulthood. Am J Public Health 2007; 97: 1489–95.http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.070359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pucci LG, Siegel M.. Exposure to brand-specific cigarette advertising in magazines and its impact on youth smoking. Prev Med 1999; 29: 313–20.http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1999.0554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choi WS, Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ. et al. Progression to established smoking: the influence of tobacco marketing. Am J Prev Med 2002; 22: 228–33.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00420-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burton S, Clark L, Jackson K.. The association between seeing retail displays of tobacco and tobacco smoking and purchase: findings from a diary-style survey. Addiction 2012; 107: 169–75.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bierut T, Krauss MJ, Sowles SJ. et al. Exploring marijuana advertising on weedmaps, a popular online directory. Prev Sci 2017; 18: 183–92.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0702-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cavazos-Rehg P, Krauss M, Grucza R. et al. Characterizing the followers and tweets of a marijuana-focused Twitter handle. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16: e157.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE. et al. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot 2005; 19: 330–3.http://dx.doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones SC, Smith KM.. The effect of point of sale promotions on the alcohol purchasing behaviour of young people in metropolitan, regional and rural Australia. J Youth Stud 2011; 14: 885–900.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2011.609538 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hurtz SQ, Henriksen L, Wang Y. et al. The relationship between exposure to alcohol advertising in stores, owning alcohol promotional items, and adolescent alcohol use. Alcohol Alcohol 2006; 42: 143–9.http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agl119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Henriksen L, Ribisl KM, Rogers T. et al. Standardized tobacco assessment for retail settings (STARS): dissemination and implementation research. Tob Control 2016; 25: i67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Colorado Department of Revenue. Marijuana License Facilities 2017.

- 29. Permanent Rules Related to the Colorado Retail Marijuana Code Marijuana Enforcement Division: East Lansing, MI. 2013.

- 30. City of Denver. Colorado’s Packaging and Labeling Requirements for Retail Marijuana for Consumer Protection and Child Safety 2016.

- 31. State of Colorado. Marijuana in Colorado: Good to Know Colorado 2017.

- 32. Thomas C, Freisthler B.. Assessing sample bias among venue-based respondents at medical marijuana dispensaries. J Psychoactive Drugs 2016; 48: 56–62.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2015.1127450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kong AY, Eaddy JL, Morrison SL. et al. Using the vape shop standardized tobacco assessment for retail settings (V-STARS) to assess product availability, price promotions, and messaging in New Hampshire vape shop retailers. Tob Regul Sci 2017; 3: 174–82.http://dx.doi.org/10.18001/TRS.3.2.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. V-STARS. Available at: http://countertobacco.org/resources-tools/store-assessment-tools/vstars/. Accessed: 9 August 2017.

- 35. Schauer GL, King BA, Bunnell RE. et al. Toking, vaping, and eating for health or fun: marijuana use patterns in adults, U.S., 2014. Am J Prev Med 2016; 50: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Feld AL, Johnson TO, Byerly KW. et al. How to conduct store observations of tobacco marketing and products. Preve Chronic Dis 2016; 13: E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reiss AJ. Systematic observation of natural social phenomena. Sociol Methodol 1971; 3: 3–33.http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/270816 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ.. Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociol Methodol 1999; 29: 1–41.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0081-1750.00059 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Freisthler B, Kepple NJ, Sims R. et al. Evaluating medical marijuana dispensary policies: spatial methods for the study of environmentally-based interventions. Am J Community Psychol 2013; 51: 278–88.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9542-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marijuana Business Daily. Chart of the Week: Sales of Marijuana Concentrates, Edibles Surging in Colorado June 2016.

- 41. Aaker DA. Measuring brand equity across products and markets. Calif Manage Rev 1996; 38: 102–20.http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/41165845 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dawes J. Cigarette brand loyalty and purchase patterns: an examination using US consumer panel data. J Bus Res 2014; 67: 1933–43.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.014 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aaker D. Building Strong Brands. New York: Free Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Morrison C, Gruenewald PJ, Freisthler B. et al. The economic geography of medical cannabis dispensaries in California. Int J Drug Policy 2014; 25: 508–15.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC. et al. Assessing the overlap between tobacco and marijuana: trends in patterns of co-use of tobacco and marijuana in adults from 2003-2012. Addict Behav 2015; 49:26–32.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler M. et al. Differences in tobacco product use among past month adult marijuana users and nonusers: findings from the 2003-2012 national survey on drug use and health. Nicotine Tob Res 2016; 18:281–8http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]