Abstract

Self-management support (SMS) initiatives have been hampered by insufficient attention to underserved and disadvantaged populations, a lack of integration between health, personal and social domains, over emphasis on individual responsibility and insufficient attention to ethical issues. This paper describes a SMS framework that provides guidance in developing comprehensive and coordinated approaches to SMS that may address these gaps and provides direction for decision makers in developing and implementing SMS initiatives in key areas at local levels. The framework was developed by researchers, policy-makers, practitioners and consumers from 5 English-speaking countries and reviewed by 203 individuals in 16 countries using an e-survey process. While developments in SMS will inevitably reflect local and regional contexts and needs, the strategic framework provides an emerging consensus on how we need to move SMS conceptualization, planning and development forward. The framework provides definitions of self-management (SM) and SMS, a collective vision, eight guiding principles and seven strategic directions. The framework combines important and relevant SM issues into a strategic document that provides potential value to the SMS field by helping decision-makers plan SMS initiatives that reflect local and regional needs and by catalyzing and expanding our thinking about the SMS field in relation to system thinking; shared responsibility; health equity and ethical issues. The framework was developed with the understanding that our knowledge and experience of SMS is continually evolving and that it should be modified and adapted as more evidence is available, and approaches in SMS advance.

Keywords: chronic illness, framework, collaboration, disease management

INTRODUCTION

Both the healthcare delivery system and public health are struggling to address the enormous impacts of chronic conditions. While prevention strategies continue to evolve and have impact, the fact remains that many people are still developing long-term illnesses that have significant costs for individuals, families, healthcare systems and society. Patient's taking an active role in managing their health—or patient self-management (SM)—is increasingly recognized as a crucial strategy for addressing the challenge of chronic disease (Galson, 2009) that may improve self-efficacy, SM behaviors and health status as well as potentially reduce healthcare costs (Barlow et al., 2002; Foster et al., 2007; Brownson et al. 2009; Brady et al., 2013). Building effective policies, programs and structures to support SM is recognized as critical to chronic disease management (Jordan and Osborne, 2007; Galson, 2009; British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2011).

A number of different self-management support (SMS) approaches are evolving in governments, health regions, professional organizations and non-profit associations. The identification of SMS as a key component in models for chronic disease care (Wagner, 1998) has undoubtedly played an important role in increasing awareness of SMS in many countries. For example, there has been major interest in SM education programs such as the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) (Lorig et al., 2006). In 2005, the UK established the Expert Patients Programme to nationally implement lay-led chronic condition SMS and, in 2007 the Expert Patients Programme Community Interest Company was established to increase the number of SM programs offered throughout the UK. In Canada, SM programs such as the CDSMP are being offered in almost every province (Paterson et al., 2009) and other SM programs such as Bounce Back: Reclaim Your Life (Canadian Mental Health Association - British Columbia Division, 2012) are becoming common (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2011). The US Administration on Aging in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service has provided $32.4 million to support the broad dissemination of the CDSMP program across the USA through the aging services network (Ory et al., 2013). Other approaches to SMS have also gained considerable support such as the Flinders Program developed in Australia (Flinders University, 2012) and Co-creating Health program (Health Foundation, 2011) that aims to embed SMS within mainstream health services in the UK. In Canada, there are an increasing number of SMS training programs being developed for healthcare providers such as the Health Coaching for SM program (Institute for Optimizing Health Outcomes, 2010) and the Practice Support Program Learning Modules (General Practice Services Committee, 2009). Some provinces have made SMS a strategic focus and are starting to consider a coordinated approach to SMS initiatives across multiple levels including primary, community and home care and social services (author 2015, submitted for publication). In 2007, the Australian government announced $515 million over 5 years for SM initiatives and training (Jordan and Osborne, 2007). In the USA, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHSs) developed a strategic framework for multiple chronic conditions that promote SM as one of four overarching goals and the National Council on Aging spearheaded the SM alliance, a partnership among government, corporate and non-profit sector organizations to achieve the SM-related goals of the Multiple Chronic Conditions Framework (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010).

In this context of flourishing activity, researchers are investigating a wide range of SMS initiatives. Authors of Cochrane, systematic and rapid reviews have concluded that CDSMPs and other SM interventions have small effects on some health outcomes (Bury et al., 2005; Newbould et al., 2006; Foster et al., 2007). Outside of reviews on individual-level interventions, the evidence base is in its infancy for other forms of SMS. However, a recent review has summarized the growing evidence base for SMS in primary healthcare (Battersby et al., 2010) and studies have begun to evaluate implementation of SMS in systems (Kennedy et al., 2014). With few exceptions (Whole Systems Informing Self-Management Engagement, Kennedy et al., 2010) most SMS work has focused on a single dimension of SMS, such as self-management education (CDSMP) or provider training (Flinders University, 2012), but does not encompass SMS broadly or address the multiple levels of the socio-ecological model (Ruiz et al., 2013). While Wagner's chronic care model has increased attention to SMS, that model focuses primarily on SMS provided in healthcare settings, and does not provide specification for the development of appropriate SMS. SMS initiatives are often centered in the healthcare domains without sufficient consideration of social environments and communities (Vassilev et al., 2011, 2013). Further, SMS developments in healthcare settings are often framed as a strategy to reduce healthcare costs by emphasizing individual responsibility for health, which has been problematized by Kendall and Rogers (Kendall and Rogers, 2007), among others. An additional challenge of many SMS approaches to date is that they do not fully address the diverse needs of the chronic condition population, particularly more disadvantaged groups (Bury et al., 2005; Dettori et al., 2005; Jordan and Osborne, 2007; Glasgow et al., 2008; Furler et al., 2011). Low-uptake, low-attendance and high-attrition rates are commonly identified challenges (Griffiths et al., 2005; Rose et al., 2008) and health literacy is increasingly recognized as hugely problematic for implementing CCSM interventions in disadvantaged populations (Schillinger, 2002; Jordan et al., 2008). Also, most SM initiatives and the broader SM movement have failed to consider important ethical dimensions inherent in the promotion and development of these strategies for chronic care management (Redman, 2005, 2007).

The purpose of this paper is to describe a strategic framework for chronic condition SMS (CCSMS) that emerged from an international consensus process. Strategic frameworks are considered tools to guide future development and provide a structure within which more detailed activities on planning and implementation can occur. They outline high-level principles and priorities rather than being prescriptive about which activities to implement as any initiatives need to be developed in relation to the environment within which they will be implemented. The specific aim of our strategic framework is to provide direction for policy-makers, planners and practitioners in developing and implementing comprehensive and coordinated approaches to SMS at national, regional or local levels. It sets out definitions of SM and SMS, a collective vision, eight guiding principles and seven strategic directions. Sample actions to enact strategic directions are also provided for illustrative purposes. The CCSMS framework has value for any policy-maker, healthcare professional, local decision maker, service provider, chronic condition-related organization, consumer advocate, researcher and/or any organization that pays for healthcare (government entities or private payers) who wants to advance SMS using a comprehensive strategic structure.

FRAMEWORK DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION PROCESS

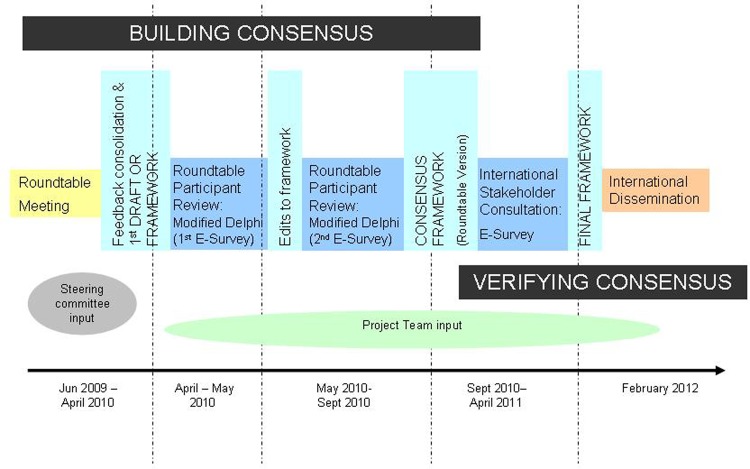

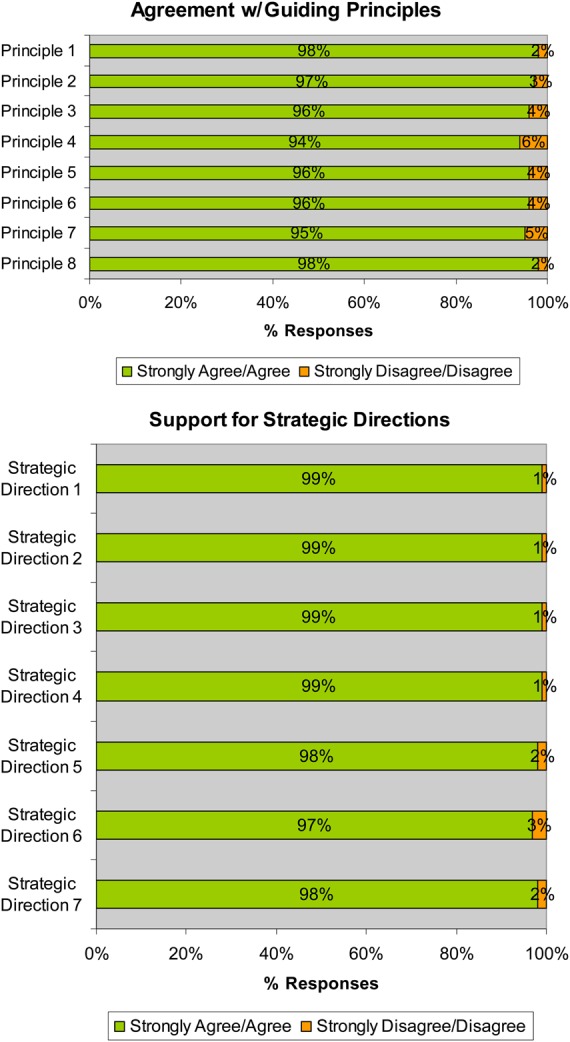

The framework development process began with an intensive 3-day roundtable discussion among 23 subject-matter experts from 5 English-speaking countries to share knowledge, discuss gaps in SMS and propose future directions (author 2011). Participants were selected by an International Steering Committee (comprised of four researchers representing each of the invited countries) to provide SM expertise from a diverse range of disciplines and sectors (academia, clinical care, government and community). A thematic analysis of meeting transcripts was used to create an initial draft framework. It was then reviewed and refined through a two-staged modified Delphi e-survey process with roundtable participants to build consensus on the framework's definitions, guiding principles, vision and strategic directions (see Appendix 1). To validate the roundtable participant framework, we engaged in a broader international stakeholder consultation via an e-survey process that resulted in feedback on the framework from 203 individuals in 16 countries (Canada, the UK, Australia, the USA, New Zealand, Sweden, the Netherlands, Austria, Brazil, Denmark, Germany, Israel, Norway, Singapore, Spain and Switzerland). Reviewers were initially obtained using a purposive sampling approach whereby we solicited names from roundtable participants, targeted email list serves, conferences and online searches. We extended email invitations to these people to review the framework and encouraged them to forward the survey to organizations and/or individuals that should be involved in the review process (snowball sampling). The respondents largely worked in universities or colleges, healthcare organizations, not-for profit community organizations and/or government organizations. They included researchers, educators, healthcare providers, policy-makers, program managers, consultants, patient group representatives, program planners and consumers (see author, 2011 for detailed participant demographics). Results from the international stakeholder e-consultation demonstrated very high levels of agreement for all content of the SMS framework (see Appendix 2). The framework development and validation process as well as details on participant characteristics are described in more detail elsewhere (author 2015, submitted for publication). Ethics approval was obtained from The University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

We recognize that the general applicability of our framework may be limited by the nature of the participants who engaged in the process. This initiative was based on the understanding that expert opinion and experience across sectors and countries is a valuable source of knowledge to support an evolving evidence-base for a field of policy and practice (Delbecq et al., 1975; Tonelli, 1999; Powell, 2003). Our consensus-building process harnessed knowledge of subject matter experts to create a roadmap for future SMS initiatives. The framework was originally developed by English-speaking participants from developed countries (with the exception of a French-speaking person from Quebec) for implementation in countries with similar characteristics. However, the validation process found strong agreement with the content from a much larger range of developed countries that were not all primarily English speaking (details described elsewhere, author 2015, submitted for publication). These findings suggest that the framework may have relevance in developed non-English-speaking countries beyond the original five countries represented at the roundtable—even though it is reasonable to assume that understandings of SMS may be different in other countries and cultures. Although we only had one participant from a developing country (Brazil), there is no reason to believe that this framework might not be useful in low-income countries, but it may be more difficult to operationalize with more resource limitations or where other social and environmental barriers may exist.

THE INTERNATIONAL CHRONIC CONDITION SELF-MANAGEMENT SUPPORT FRAMEWORK

The purpose of the International Framework for Chronic Condition Self-Management Support is to help stakeholders (policy-makers, healthcare professionals, local decision makers, service providers, chronic condition-related organizations, consumer advocates, researchers and healthcare payers) in a variety of sectors influence policy, practice and research developments related to SMS for chronic conditions. It aims to promote the development and evaluation of effective interventions and support mechanisms that consider and value the diverse ways people adapt to and live with chronic conditions and encourage integration of these SMS initiatives into health, social and community settings. We hope the framework will ultimately help to strengthen our capacity for supporting people with chronic conditions, reduce health inequities and improve health in chronic-condition populations.

Collective vision

This framework reflects a commitment to fostering a culture that creates structures, enacts policies and offers services to reduce the impact of chronic conditions and support people's SM behaviors. SMS services should provide individuals and their families with a menu of effective options and opportunities to engage in SM that appropriately fit their needs and optimizes their health and well-being. Such services should also enhance health and reduce health inequities in chronic-condition populations.

Conceptualizations of SM and SMS

SM incorporates all of the tasks that individuals engage in to manage their symptoms, treatments and the physical, emotional and social impacts of living with chronic conditions in daily life (Barlow et al., 2002). Health, social and physical environments influence individuals' and their families' capacities to self-manage. Many aspects of life such as income, education, ethnicity and gender—as well as related constraints of services, structures and environments—play an important role in SM attitudes and behaviors; these factors are sometimes referred to as social determinants of health.

Individuals and their families self-manage chronic conditions in the context of their daily lives which often include interactions with a wide range of support services. SMS is a grouping of structures, systems, policies, services and programs that extend across healthcare, social sectors and communities to support and improve the way people manage their own chronic conditions and optimize their health, and live well. SMS can increase people's capacity to live well with chronic conditions by addressing some of the broad social and individual factors that influence their behavior, and is a shared responsibility between individuals and society.

SMS adapts and responds to the social contexts of individuals and their families, and local and community needs, and builds on and integrates peoples' experiences of living with and managing chronic conditions. SMS includes: (i) infrastructures and policies that minimize conditions and barriers that limit people's capacity to self-manage chronic conditions; (ii) services and programs (such as those provided by healthcare providers and community-based organizations) that support individuals and their families to engage in SM and feel happy and fulfilled to make the most of their lives despite the condition and (iii) skills, resources and social networks people have in their daily lives.

SMS resources provide people living with chronic conditions with access to timely information, informed guidance, supportive interventions and confidence-building tools that can facilitate participation and partnership in health and social care, decision-making and social engagement in order to achieve the best possible medical, social and psychological results. SMS programs can: involve individuals, families and social networks; take place in a wide range of environments such as homes, workplaces, hospitals and community settings (e.g. community centers and schools); be delivered by a wide range of services and organizations including primary care, home care and social services and disability and non-government agencies; and be provided through one-on-one or group interactions, or via electronic means (e.g. Internet, texting and telephone).

Guiding principles

Eight guiding principles reflect shared values and priorities for advancing the field of SMS. They are overarching statements that can help to guide decision-making processes and promote a value-based approach to policy and program development (see Table 1).

Table 1:

Guiding principles

| Guiding principles |

|---|

| 1. Informed by evidence and evolve in response to the needs of the chronic condition population |

| 2. Centred on the person or family and reflect the differing goals, needs and preferences of individuals and their differing social contexts |

| 3. Focused on improving an individual's capacity to be healthy and live well according to their values |

| 4. Created to be equally available, appropriate and accessible to all persons with chronic conditions |

| 5. Developed to promote benefits and minimize potential harms |

| 6. Implemented in ways that respect an individual's choice, autonomy and rights to determine their own goals and participation in SMS |

| 7. Embedded in the management and treatment of chronic conditions |

| 8. Integrated across the continuum of health and community services from prevention to palliative care |

Strategic directions

Seven key strategies have been identified to promote SMS in research, policy and practice. Stakeholders (e.g. policy-makers, healthcare professionals, local decision makers, service providers, chronic condition-related organizations, consumer advocates, researchers and healthcare payers) can use these strategic directions to move SMS forward at local, community, regional, provincial/state and/or national levels. Sample actions provide ideas on how to address strategic directions, but specific initiatives must be developed in response to the needs, resources and systems in specific contexts (see Table 2). It is recognized that some strategic directions maybe more relevant to particular organization or groups either based on their area of focus (policy, practice or research, for example) or where an organization is at with SMS developments (infancy or well developed). As with all strategic frameworks, users prioritize what is most relevant to their purposes and this will likely shift over time.

Table 2:

Seven strategic directions and sample actions

| Strategy 1 |

| Support people with chronic conditions and their families to be meaningfully engaged in decision-making, planning and evaluation of SMS initiatives |

| Sample actions |

|

| Strategy 2 |

| Expand reach and range of, and access to, SMS interventions, programs and services in healthcare systems and communities |

| Sample actions |

|

| Strategy 3 |

| Advance evidence on the effectiveness and appropriateness of SMS interventions and other kinds of SMS-related initiatives |

| Sample actions |

|

| Strategy 4 |

| Improve quality of SMS services, programs and interventions |

| Sample actions |

|

| Strategy 5 |

| Forge and strengthen linkages within and between sectors, policies, programs and service providers |

| Sample actions |

|

| Strategy 6 |

| Foster leadership, commitment and accountability for SMS at all levels of healthcare and social and community services |

| Sample actions |

|

| Strategy 7 |

| Build infrastructure to support SMS initiatives and provide resources and funding to support these initiatives |

| Sample actions |

|

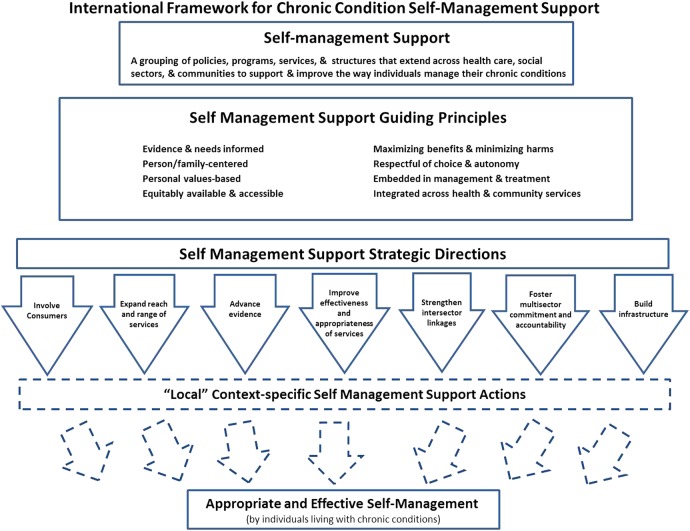

A schematic representation of the key elements of the framework is found in Figure 1.

Fig. 1:

Schematic representation of the International Framework for Chronic Condition Self-Management Support.

The principles are foundational values though which we should view all SMS efforts. The strategic directions are where movement and development need to occur in SMS field. The local context specific actions are where operationalization of initiatives needs to happen. Specific actions and activities should be developed by people with knowledge of local needs and context and be relevant to an organization's mission and goals.

DISCUSSION

The framework combines important and relevant SM issues into a comprehensive strategic document that provides value to the SMS field to two important ways. At a practical level, it provides principles and strategies that can help decision-makers plan SMS initiatives. The operationalization of the framework will be facilitated by: organizations and people with a strong commitment to SMS principles; prior experience with SMS initiatives; a system of care that integrates health and social services; a patient-oriented system with well-developed mechanisms of engagement, strong quality improvement culture and available resources for innovation and development, to name a few. Barriers can potentially include fragmented systems, lack of integration of primary and community services, weak leadership and commitment as well as insufficient resources for program development and evaluation. A more detailed understanding of how to operationalize the framework will evolve as we collect information from policy and practice environments using it. These data will enable researchers to identify important contextual factors that influence the uptake of the principles and strategies and shape the nature of the local actions on SMS.

It also provides value by catalyzing and expanding our thinking about the SMS field in four key directions: (i) system thinking; (ii) shared responsibility; (iii) health equity and (iv) ethical dimensions. These four themes emerged in our roundtable discussions in response to identified gaps and were solidified through Delphi and the e-validation process. Collectively, they create a broad conceptualization that underpins the framework content and represent a simple yet important paradigm shift from historical approaches and thinking on SMS. The framework emphasizes the importance of situating SM within a broader systems perspective where the focus is on supports for chronic condition SM across the continuum of services that people use in daily life when living with long-term illness. System thinking helps to illuminate the bigger picture of care, but also the wider context and interactions among different services and activities (Leischow and Milstein, 2006). In many places, SMS is being driven within the healthcare sector as an essential piece of chronic disease management as outlined in the Chronic Care Model (Wagner, 1998) and the Expanded Care Model (Barr et al., 2003), but it is increasingly recognized that personal communities, voluntary and community groups and social services play an equally important role in SMS developments (Fisher et al., 2007; Vassilev et al., 2011, 2013). The framework definition of SMS includes social sectors, communities and families in supporting and improving the way people manage their chronic conditions which differs from other healthcare centric definitions that dominant the SMS field (e.g. Institute of Medicine 2003; British Columbia Ministry of Health, http://www.selfmanagementbc.ca/). The framework also emphasizes that SM of chronic conditions is a shared responsibility between individuals and society. SM behaviors are influenced by broader social determinants of health as well as individual level factors (Fisher et al., 2005). The framework acknowledges that many factors, including income, education, ethnicity, and gender, in addition to related constraints of services, structures and environment play an important role in SM attitudes and behaviors. Further, the framework brings issues of health equity to the forefront of SMS considerations. It states the importance of ensuring that SMS interventions, programs and services are accessible to all who can benefit, but also acknowledges that specific programs should be developed to target more vulnerable, disadvantaged and hard to reach populations. Perhaps most importantly, the framework also draws attention to important ethical dimensions of SMS, most notably, the need for decision makers to consider that SMS approaches might not work for everyone, or be desirable to all people living with chronic conditions and that they could potentially cause harm for certain individuals or groups who may not have the capacity or resources to self-manage (Redman, 2005, 2007).

Reviewers of the framework have demonstrated high interest in using the framework to direct work in many areas including SMS practice and patient care, and policy development and implementation and future research. The framework is designed to guide the SMS development process so regardless of whether it is a small town hospital in the USA, a provincial government in Canada or the National Health Service in the UK, the framework identifies facets to be considered in developing SMS for particular groups and a structure for developing a comprehensive approach. The National Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA) has used the CCSMS framework’s SMS definition to ground its public health approach to SMS and its seven strategic directions as a structure for organizing their activities (Brady et al., 2015). The framework has also been used as a lens to organize evidence on chronic disease approaches within older ethnic minority populations in Canada (Koehn et al., 2011). Although the framework has not been formally released, we have anecdotal reports that suggest its potential value at educational, policy and practice levels. A number of international reviewers suggested that the framework could be used for training purposes—both in formal education curricula, but also in building knowledge and capacity of healthcare professionals. Decision makers have described how the framework is providing a vehicle for sharing and disseminating emerging understandings to policy-makers, practitioners, consumers and organizations to help clarify the boundaries of the SMS field and integrate SMS into healthcare, social and community services. We have also been told that the framework has been used as a guiding document for the development of provincial and international SMS initiatives (personal communications: Karen Anzai, 11 March 2013; Sandra Mann, 16 February 2012; Dr Miriam Heijnders, 22 May 2013).

Looking ahead

The framework promotes the development and evaluation of effective interventions and supports mechanisms across multiple levels of the health-social system that value the diverse ways people adapt to, and live with chronic conditions. It encourages the integration of SMS initiatives into health, social and community settings. Feedback collected on the framework during the consensus building process suggest that future iterations of the framework could offer a more in-depth consideration of patient centeredness, mental health, social justice, culture and ethnicity and gender and diversity. There is a need for structures and resources to support the implementation of the framework's strategic directions as well as for research to evaluate the utility of this type of framework in advancing a developing field of knowledge and practice. Building an extensive reference list of research evidence that supports the strategic directions, creating a list of potential implementation approaches and disseminating case studies of effective SMS approaches may be helpful. Identifying mechanisms for collaborative research (e.g. studies synthesizing evidence on SM interventions and other SMS initiatives) could also be beneficial for the SMS community to further knowledge development. Given the disproportionate burden of chronic diseases in low-income countries, it is imperative that we consider how the framework might be used in regions beyond our consultative scope. One possible process would be to convene stakeholders in the country of interest and ask them to assess how relevant the guiding principles and strategic directions are in their cultural, political and economic context and healthcare system(s) and to make recommendations on how to adapt the framework to best suit their needs.

In summary, the CCSMS framework reflects an urgent need to build consensus on how to best move forward in SMS given the increasing activity at policy and practice levels and absence of solid evidence in all developing areas. It provides guidance for how we approach SMS nationally and internationally and should continually evolve as more evidence is available and approaches and understandings in SMS develop. It is our sincere hope that the framework will stimulate essential discussions and debates that can advance SMS research, policy and practice in the years to come.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant numbers FRN 126839 for the roundtable and KTB 101890 for the framework development and international review process). The roundtable meeting received additional financial support from the University of Victoria, University of New South Wales Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity, Women’s Health Research Network, Heart and Stroke Foundation of British Columbia and Yukon, British Columbia Lung Association, and the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. The roundtable was also made possible through the financial support of AstraZeneca Canada, Inc. and Merck Frosst Canada Ltd. In-kind support for the roundtable was provided by the BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, NEXUS: Researching the Social Contexts of Health Behaviour and the Interdisciplinary Capacity Enhancement: Bridging Excellence in Respiratory Disease and Gender Studies (ICEBERGS) research groups at the University of British Columbia, British Columbia Medical Association, Healthy Heart Society, ImpactBC and the Disability Resource Network.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Roundtable Steering Committee: Dr Sue Mills (PI), Dr Richard Osborne (Co-I), Dr Teresa Brady, Dr Anne Rogers and Ms Elizabeth Vanden. Roundtable participants: Dr Tom Blakeman, Ms Carol Brownson, Dr Sarah Dennis, Mr Bill Conolly, Ms Patricia Flanagan, Dr Kate Lorig, Dr Bob Lewin, Dr Patrick McGowan, Ms Kelly McQuillen, Dr Tanya Packer, Dr Robert Perreault, Dr Barbara Redman, Dr Richard Reed, Dr Peter Sargious, Ms Joan Watterson, Dr Edward Wagner, Dr Davidicus Wong and Dr Sally Wyke. SMS Expert Informants: Dr Ruth Anderson, Dr Malcolm Battersby, Ms Rhonda Carriere, Ms Martha Funnell, Dr John Furler, Dr Elizabeth Kendall, Dr Stan Newman, Dr Peter Sargious, Ms Leslie Schroeder, Dr Sally Thorne, Dr Peter Tugwell, Dr Durhane Wong-Rieger. We thank the following individuals for their assistance with the roundtable and/or framework development process: Ms Patrice Allen, Ms Gemma Hunting, Ms Myriam Laberge (facilitator), Ms Anna Liwander, Ms Katherine Nichol, Ms Lisa May, Ms Louise Pitman, Ms Nancy Poole and Ms Eliza Seaborn. In addition, we thank the staff of the BC Centre of Excellence for Women's Health for their support during this project.

APPENDIX 1

Graph 1:

Percentage of agreement with guiding principle, international e-survey.

APPENDIX 2

Graph 2:

Percentage of agreement with strategic directions, international e-survey.

REFERENCES

- Barlow J., Wright C., Sheasby J., Turner A., Hainsworth J. (2002) Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Education and Counseling, 48, 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr V. J., Robinson S., Marin-Link B., Underhill L., Dotts A., Ravensdale D. et al. (2003) The expanded chronic care model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the chronic care model. Hospital Quarterly, 7, 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battersby M., Von Korff M., Schaefer J., Davis C., Ludman E., Greene S. et al. (2010) Twelve evidence-based principles for implementing self-management support in primary care. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 36, 561–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady T. J., Murphy L., O'Colmain B. J., Beauchesne D., Daniels B., Greenberg M. et al. (2013) A meta-analysis of health status, health behaviors, and healthcare utilization outcomes of the chronic disease self-management program. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10, 120112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady T. J., Anderson L. A., Kobau R. (2015). Chronic disease self-management support: public health perspectives. Frontier in Public Health, http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00234 (1 June 2015, date last accessed). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Ministry of Health. (2011) Self-management Support: A Healthcare Intervention. British Columbia Ministry of Health, Victoria, BC. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson C. A., Hoerger T. J., Fisher E. B., Kilpatrick K. E. (2009) Cost-effectiveness of diabetes self-management programs in community primary care settings. The Diabetes Educator, 35, 761–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M., Newbould J., Taylor D. (2005) A Rapid Review of the Current State of Knowledge Regarding lay-led Self-Management of Chronic Illness: Evidence Review. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Mental Health Association - British Columbia Division (2012) Bounce Back: Reclaim Your Health. http://www.cmha.bc.ca/how-we-can-help/adults/bounceback (13 March 2014, date last accessed).

- Delbecq A. L., Van de Ven A. H., Gustafson D. H. (1975) Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes. Scott, Foresman and Co, Glenview, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Dettori N., Flook B. N., Pessl E., Quesenberry K., Loh J., Harris C. et al. (2005) Improvements in care and reduced self-management barriers among rural patients with diabetes. The Journal of Rural Health, 21, 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E. B., Brownson C. A., O'Toole M. L., Shetty G., Anwuri V. V., Glasgow R. E. (2005) Ecological approaches to self-management: the case of diabetes. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 1523–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E. B., Brownson C. A., O'Toole M. L., Anwuri V. V., Shetty G. (2007) Perspectives on self-management from the diabetes initiative of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Diabetes Educator, 33, 216S–224S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinders University (2012) The Flinders Program™. http://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/fhbhru/self-management.cfm (13 March 2014, date last accessed).

- Foster G., Taylor S. J. C., Eldridge S., Ramsay J., Griffiths C. J. (2007) Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, 4, 1–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furler J., Harris M., Rogers A. (2011) Equity and long-term condition self-management. Chronic Illness, 7, 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galson S. K. (2009) Self-management programs: one way to promote healthy aging. Public Health Reports, 124, 478–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Practice Services Committee (2009) Practice Support Program. http://www.gpscbc.ca/practice-support-program (13 March 2014, date last accessed).

- Glasgow N. J., Jeon Y. H., Kraus S. G., Pearce-Brown C. L. (2008) Chronic disease self-management support: the way forward for Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 189, S14–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths C., Motlib J., Azard A., Ramsay J., Eldridge S., Feder G. et al. (2005) Expert Bangladeshi patients? Randomised controlled trial of a lay-led self-management programme for Bangladeshi patients with chronic disease. British Journal of General Practice, 55, 831–837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Foundation (2011) Co-creating Health. http://www.health.org.uk/areas-of-work/programmes/co-creating-health/ (13 March 2014, date last accessed).

- Institute for Optimizing Health Outcomes (2010) Institute for Optimizing Health Outcomes. http://www.optimizinghealth.org/ (13 March 2014, date last accessed).

- Institute of Medicine (2003). Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality. In Adams K., Corrigan J. M., eds. National Academy Press, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan J. E., Osborne R. H. (2007) Chronic disease self-management education programs: challenges ahead. Medical Journal of Australia, 186, 84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan J. E., Briggs A. M., Brand C. A., Osborne R. H. (2008) Enhancing patient engagement in chronic disease self-management support initiatives in Australia: the need for an integrated approach. The Medical Journal of Australia, 189, S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall E., Rogers A. (2007) Extinguishing the social?: state sponsored self care policy and the Chronic Disease Self management Programme. Disability & Society, 22, 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A., Chew-Graham C., Blakeman T., Bowen A., Gardner C., Protheroe J. et al. (2010) Delivering the WISE (Whole Systems Informing Self-Management Engagement) training package in primary care: learning from formative evaluation. Implementation Science, 5, 7 doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A., Rogers A., Chew-Graham C., Blakeman T., Bowen R., Gardner C. et al. (2014) Implementation of a self-management support approach (WISE) across a health system: a process evaluation explaining what did and did not work for organisations, clinicians and patients. Implementation Science, 9, 129 doi:10.1186/s13012-014-0129-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehn S., Jarvis P., Kobayashi K. (2011) Taking care of chronic disease: Realizing approaches for Canada's aging ethnic population: A workshop. Final Report iCARE Immigrant Older Adults Care Accessibility Research Empowerment, Vancouver, BC. [Google Scholar]

- Leischow S. J., Milstein B. (2006) Systems thinking and modeling for public health practice. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 403–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K., Holman H., Sobel D., Laurent D., Gonzalez V., Minor M. (2006) Living A Healthy Life with Chronic Conditions. Bull Publishing Company, Boulder, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Newbould J., Taylor D., Bury M. (2006) Lay-led self-management in chronic illness: a review of the evidence. Chronic Illness, 2, 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory M. G., Smith M. L., Kulinski K. P., Lorig K., Zenker W., Whitelaw N. (2013) Self-management at the tipping point: reaching 100,000 Americans with evidence-based programs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61, 821–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson B., Kealey L., MacKinnon R., McGibbon C., Van den Hoonaard D., LaChapelle D. (2009) Chronic Diseases Self-Management Practice in Canada: Patterns, Trends and Programs. Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON. [Google Scholar]

- Powell C. (2003) The Delphi technique: myths and realities. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41, 376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman B. K. (2005) The ethics of self-management preparation for chronic illness. Nursing Ethics, 12, 360–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman B. K. (2007) Responsibility for control: ethics of patient preparation for self-management of chronic disease. Bioethics, 21, 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A., Kennedy A., Bower P., Gardner C., Gately C., Lee V. et al. (2008) The United Kingdom Expert Patients Programme: results and implications from a national evaluation. The Medical Journal of Australia, 189, S21–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M. A., Arenson C., Harrod P., Salkey R., Santana A., Diamond J. (2008) Evaluation of the chronic disease self-management program with low-income, urban, African American older adults. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 25, 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz S., Brady T. J., Glasgow R., Birkel R. (2013) Chronic condition self-management surveillance: what is and should be measured? Preventing Chronic Disease, 10, 120–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D. (2002) Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288, 475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli M. R. (1999) In defense of expert opinion. Academic Medicine, 74, 1187–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2010) Multiple Chronic Conditions— A Strategic Framework Optimum Health and Quality of Life for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Conditions. US. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev I., Rogers A., Sanders C., Kennedy A., Blickem C., Protheroe J. et al. (2011) Social networks, social capital and chronic illness self-management: a realist review. Chronic Illness, 7, 60–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev I., Rogers A., Blickem C., Brooks H., Kapadia D., Kennedy A. et al. (2013) Social networks, the ‘work’ and work force of chronic illness self-management: a survey analysis of personal communities. PLoS One, 8, e59723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E. H. (1998) Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice, 1, 2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]