Abstract

Objective

To summarise the evidence on determinants of health-related quality of life (HRQL) in Asian patients with breast cancer.

Design

Systematic review conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42015032468).

Methods

According to the PRISMA guidelines, databases of MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase and PsycINFO were systematically searched using the following terms and synonyms: breast cancer, quality of life and Asia. Articles reporting on HRQL using EORTC-QLQ-C30, EORTC-QLQ-BR23, FACT-G and FACT-B questionnaires in Asian patients with breast cancer were eligible for inclusion. The methodological quality of each article was assessed using the quality assessment scale for cross-sectional studies or the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies.

Results

Fifty-seven articles were selected for this qualitative synthesis, of which 43 (75%) were cross-sectional and 14 (25%) were longitudinal studies. Over 75 different determinants of HRQL were studied with either the EORTC or FACT questionnaires. Patients with comorbidities, treated with chemotherapy, with less social support and with more unmet needs have poorer HRQL. HRQL improves over time. Discordant results in studies were found in the association of age, marital status, household income, type of surgery, radiotherapy and hormone therapy and unmet sexuality needs with poor global health status or overall well-being.

Conclusions

In Asia, patients with breast cancer, in particular those with other comorbidities and those treated with chemotherapy, with less social support and with more unmet needs, have poorer HRQL. Appropriate social support and meeting the needs of patients may improve patients’ HRQL.

Keywords: breast cancer, health-related quality of life, patient-reported outcomes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review included over 75 determinants of health-related quality of life in Asian patients with breast cancer.

Studies included had varying patient selection criteria, which may be the reason for discordance results in certain determinants.

We were not able to conduct a meta-analysis to provide a sense of the level of association, as the choice of statistical analysis varied across studies.

Introduction

In Asia, the number of breast cancer survivors is increasing, with 5-year survival rates exceeding 90% in early-stage disease.1–7 This is due to improved breast cancer treatments and early detection.8–11 As such, the number of survivors is increasing rapidly. Patient-reported outcomes on health-related quality of life (HRQL), such as physical and emotional functioning and treatment-related side effects including pain, nausea and fatigue, are increasingly important as it effects many breast cancer survivors.

Impaired HRQL is best represented as gap between an individual’s actual functional level and his or her ideal standard.12 Studies from the West reported reduced physical and emotional functioning in patients with breast cancer shortly after treatment.13–16 Breast-conserving surgery as compared with mastectomy, axillary clearance, radiotherapy and chemotherapy were associated with higher level of pain.17 Furthermore, younger patients with breast cancer reported better physical functioning but more impaired emotional functioning compared with older breast cancer patients.13–16 HRQL improves until up to 6–10 years following breast cancer diagnosis.18 In Asian population, determinants of HRQL are increasingly being studied.

So far, mainly studies from Western developed countries investigated HRQL following breast cancer.14–16 19 20 However, cultural and habitual practices such as the use of traditional medicine may limit the generalisability of results from HRQL studies in Caucasian patients with breast cancer to Asian patients with breast cancer.21 22 Drug tolerance is different across populations; paclitaxel in the Japanese population is less well tolerated than the USA.23 24 Furthermore, Asian patients with breast cancer tend to be younger at diagnosis and have more advanced stages at diagnosis than Caucasians.25 Even within Asian ethnicities, Malay patients with breast cancer were found to respond better to tamoxifen therapy than Chinese or Indian patients.26 Better understanding of risk factors for poorer HRQL in Asian patients with breast cancer would allow for targeted interventions.

As an overview of the literature on HRQL determinants in Asian breast cancer survivors is currently lacking, this review systematically summarises determinants of HRQL in breast cancer survivors from Eastern, South Central and Southeast Asia.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42015032468).27

Search strategy

Databases of MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase and PsycINFO were systematically searched, using the terms ‘breast cancer’, ‘quality of life’ and ‘Asia’ in the search strategy (table 1). The systematic search was last updated on 12 July 2017.

Table 1.

Search strategy from MEDLINE filters: publication date from 1 January 2000 to 16 February 2016; English

| Search strategy (MEDLINE) | |

| #1 | “Breast Neoplasms”[MeSH] OR ((breast[Title/Abstract] OR mamma[Title/Abstract] OR mammary[Title/Abstract]) AND (carcinoma[Title/Abstract] OR carcinomas[Title/Abstract] OR carcinomatosis[Title/Abstract] OR tumor[Title/Abstract] OR tumors[Title/Abstract]) OR tumour[Title/Abstract] OR tumours[Title/Abstract] OR neoplasma[Title/Abstract] OR neoplasms[Title/Abstract]) OR cancer[Title/Abstract]) OR cancers[Title/Abstract])) |

| #2 | “quality of life”[MeSH Terms] OR “quality of life”[Title/Abstract] OR hrHRQL[Title/Abstract] OR HRQL[Title/Abstract] OR hrql[Title/Abstract] OR “Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy”[Title/Abstract] OR “FACT B”[Title/Abstract] OR “FACT-B”[Title/Abstract] OR “FACT G”[Title/Abstract] OR “FACT-G”[Title/Abstract] OR “European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer” OR “EORTC QLQ C30”[Title/Abstract] OR “EORTC”[Title/Abstract] OR “EORTC-QLQ-C30” [Title/Abstract]) OR “EORTC QLQ BR23”[Title/Abstract] OR “EORTC-QLQ-BR23”[Title/Abstract] |

| #3 | “Asia, Southeastern”[Mesh] OR “India”[Mesh] OR ‘Far East’(Mesh) OR “Southeast asia” OR “South eastern asia” OR “South central” OR China OR Chine* OR Hong Kong OR Hong Kong* OR Macau OR Tibet OR Tibet* OR Japan OR Japan* OR Korea OR Korea* OR Mongolia OR Mongoli* OR Taiwan OR Taiwan* OR India OR India* OR Brunei OR Brunei* OR Indonesia OR Indonesia* OR Lao OR Lao* OR Malaysia OR Malay* OR Myanmar OR Burmese OR Philippin* OR Singapore OR Singapore* OR Thailand OR Thai* OR Timor-Leste OR Timor* OR Vietnam OR Vietnam* |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included based on the following criteria: (1) the study population was on women diagnosed with breast cancer living in Eastern Asia, South Central Asia or Southeast Asia; (2) the study was on demographics, clinical, treatments or other determinants of HRQL; (3) the study measured quality of life using European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer – Quality of Life Questionnaire, Breast cancer module, EORTC-QLQ-C30, (with or without the breast cancer module, EORTC-QLQ-BR23), or Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G) or Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast (FACT-B) questionnaires; (4) the outcome was HRQL measured quality of life using EORTC-QLQ-C30 (with or without EORTC-QLQ-BR23), or FACT-G or FACT-B questionnaires; and (5) the study design was either cross-sectional or observational longitudinal studies. Studies published before 2000, in language other than English, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, pilot studies and studies with qualitative analyses, were not included in the current review.

Data extraction

After removal of duplicates, all titles and abstracts of the remained retrieved articles were screened. Full-text articles of potentially relevant papers were assessed for eligibility by two authors independently (PJH and SAMG). Disagreement was resolved through consensus. Data extraction was performed by two authors independently (PJH and SAMG). The following determinants were collected for each study: (1) study characteristics (year and country of publication, study design, sample size, response, median follow-up and period), (2) demographics of the study population (age, ethnicity and time since diagnosis), (3) tumour characteristics (invasive or in situ and stage) and (4) past and current treatment.

Outcome extraction included HRQL, as measured by the global health status of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and overall well-being subscales of FACT-G or FACT-B. The EORTC-QLQ-C3028–31 and FACT-G and FACT-B32–34 are validated in different populations in different languages. Other domains of the EORTC-QLQ-C30, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, fatigue, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulty were extracted where available. The EORTC-QLQ-BR23, an additional breast cancer module, assesses areas that are specific to patients with breast cancer: body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment, future perspectives, systemic therapy side effects, breast symptoms and arm symptoms. Similarly, determinants of other domains of FACT-G, physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being were extracted. The FACT-B, an extended version of the FACT-G, has an additional breast cancer subscale.

Quality assessment

Critical appraisal was performed using the quality assessment scale for cross-sectional studies,35 and an adapted version of Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies.36 The maximum score attainable was 8 for each cross-sectional study and 6 for each longitudinal study. Four items on sample selection, one on comparability and three on outcome measurement, were assessed for cross-sectional studies (online supplementary table 1). Two items on sample selection, one on comparability (score of 0–2) and two on outcome measurement, were assessed for cohort studies (online supplementary table 2). Meeting all criteria in the category would confer a high score in the category. Except for the comparability criterion of cross-sectional study, studies that meet <50% of the criteria would be considered as having a low score.

bmjopen-2017-020512supp001.pdf (344.3KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the development of the research question, choice of outcome measures or the design and conduct of this systematic review.

Results

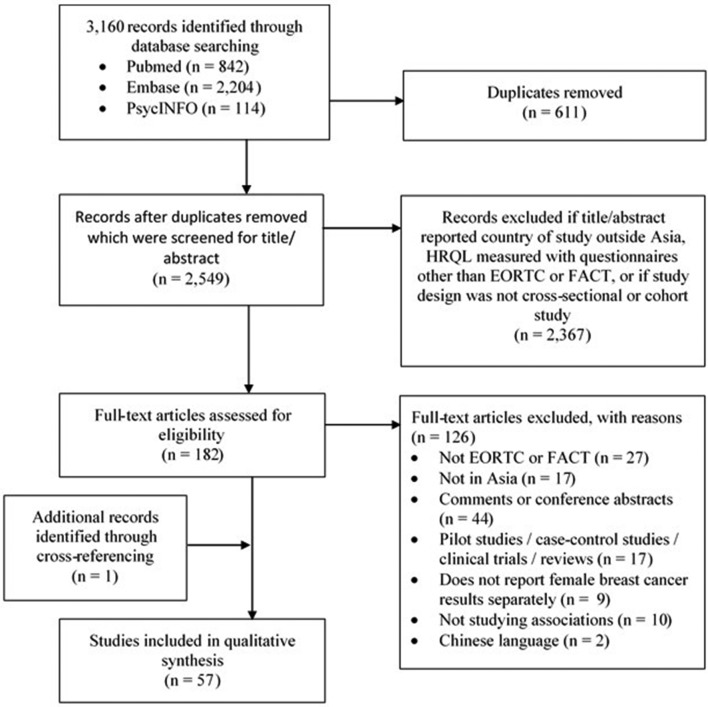

The systematic search yielded a total of 3160 records including 2549 unique articles that were screened for title and abstract using the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (figure 1). After screening the full text of 182 articles, 126 articles did not meet our inclusion and exclusion criteria (figure 1). Cross-referencing identified one additional article. In total, 57 articles were included in the systematic review (43 cross-sectional studies and 14 longitudinal studies), including 24 538 women diagnosed with breast cancer from the following seven countries: Korea (n=17), China (n=14), India (n=8), Taiwan (n=6), Malaysia (n=6), Japan (n=5) and Thailand (n=1) (table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection. HRQL, health-related quality of life.

Table 2.

Description of identified studies

| Author, year | Study design | Questionnaire | Ethnicity | Sample size (response rate, %) | Period of recruitment | Time of questionnaire assessment | Age, mean (SD) | Tumour stage | Quality assessments (max 6 or 8)^ |

| Noh et al, 200872 | Cross-sectional | C30 | Japanese | 2085 (26) | 2004 | 4.2 (1.3–11.9) years since surgery* | 57.8% were aged ≥50 years | In situ, I–IV | 7 |

| Akechi et al, 201070 | Cross-sectional | C30 | Japanese | 408 (97) | 2006–2007 | 2.8 (3.7) years since diagnosis | 56.1 (12.1) | In situ, I–IV | 6 |

| Edib et al, 201648 | Cross-sectional | C30 | Malay, Chinese and Indian | 117 (80) | 2014 | 42.7% were 1–2 years, 42.7% 2–5 years, 14.6% were >5 years since diagnosis | 13.7% were aged <40 years, 24.8% were aged 40–49, 61.6% were aged ≥50 years | In situ, I–IV | 6 |

| Kim et al, 201291 | Cross-sectional | C304 | Korean | 136 (83) | 2010–2011 | 2.6 (2.1) years since diagnosis | 50 (7.8) | In situ, I–III | 6 |

| Huang et al, 201750 | Cross-sectional | C30 | Chinese | 252 | – | 5.6 (2.6) years since diagnosis | 54.5 (8.3) age at time survey | I–IV | 4 |

| Liang et al, 201654 | Cross-sectional | C303 | Chinese | 201 | – | 4.2 (5.4) years since diagnosis | 53.6 (9.5) | In situ, I–IV | 3 |

| Jang et al, 201392 | Longitudinal | C303 | Koreans | 284 (81) | 2008–2009 | Within 5 days of surgery | 49.8 (9.5) | In situ, I–IV | 5 |

| Wani et al, 201239 | Longitudinal | C30 | Indian | 81 | – | During chemotherapy or radiotherapy | 46.6 (10.2) | – | 3 |

| Yusuf et al, 201353 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Chinese, Malay (Malaysia) |

79 (96) | 2010–2011 | Newly diagnosed before the start of treatment | Malay: 50.7 (95% CI 48.1 to 53.3) Chinese: 50.2 (95% CI 43.8 to 56.8)ᶣ |

I–IV | 6 |

| Kim et al, 201561 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Korean | 531 (61) | – | – | BCS: 48.4 (8.7), TM: 49.3 (7.5), TM-R: 43.5 (9.2) |

In situ, I–III | 6 |

| Chui et al, 201521 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Chinese, Malay, Indian, other (Malaysia) |

546 (89) | 2012–2013 | On chemotherapy | – | In situ, I–IV | 6 |

| Lee et al, 200767 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Korean | 152 | – | 1.8 (0.5–10.7) years since recurrence* | 65.8% were aged <50 years | I–III | 6 |

| Sun et al, 201462 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Korean | 407 (80) | 2011–2012 | BCS: 4 (1.6), TM: 4.1 (1.8), TM-R: 4.7 (1.9) |

BCS: 52.3 (8.5), TM: 51.9 (8.9), TM-R: 45.2 (7.5) |

In situ, I–III | 6 |

| Okamura et al, 200593 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Japanese | 59 (85) | 2001–2002 | – | 53 (10) | All patients at first recurrence, with 98% stage IV | 5 |

| Huang et al, 201060 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Chinese (Taiwan) | 130 (100) | 2004–2007 | Completed surgery or final course of chemotherapy for at least 9 months | BCS: 51.1 (22–78) TM: 55.1 (32–77)ᶣ |

In situ, I–III | 5 |

| Kang et al, 201222 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Korean | 399 (60) | 2008–2009 | CAM users: 2.7 (2.2), Non-CAM users: 2 (1.6) years since diagnosis |

CAM users: 50.6 (9.4), non-CAM users: 50.6 (11.1) | In situ, I–IV | 5 |

| Park et al, 201258 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Korean | 59 (30) | 2007–2010 | – | 56.31 (94.5) | I–IV | 5 |

| Tang et al, 201673 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Chinese | 6188 | – | – | 56.9 (9.0) | In situ, I–IV | 5 |

| Kang et al, 201794 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Korean | 283 (81) | – | At least 1 year since diagnosis | 48.5 (7.8) age at time of survey | In situ, I–III | 5 |

| Dubashi et al, 201059 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Indian | 51 (51) | – | 5 (2–11) years since diagnosisᶣ | 35 | I–III | 4 |

| Shin et al, 201795 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Korean | 231 | 2012–2015 | 13.4% were 0.5–1 year, 74.5% 1–5 years, 11.7% ≥5 years since surgery | 48.1 (8.4) | I–III | 4 |

| Chang et al, 201449 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Korean | 126 | 2009 | – | 47.7 (8.1) | I–III | 3 |

| Sharma and Purkayastha, 201796 | Cross-sectional | C30+BR23 | Indian | 60 | 2014–2016 | On radiotherapy | Mean 47.6 (range 30–75) | II–III | 2 |

| Kao et al, 201546 | Longitudinal | C30+BR23 | Chinese (Taiwan) | 408 (81) | 2010–2012 | Before surgery | 52.2 (9.6) | In situ, I–IV | 6 |

| Munshi et al, 201038 | Longitudinal | C30+BR23 | Indian | 255 (76) | – | During radiotherapy | – | In situ, I–III | 5 |

| Lee et al, 201178 | Longitudinal | C30+BR23 | Korean | 299 (81) | 2004–2006 | Within days/weeks of diagnosis | 46.6 (10) | I–IV | 5 |

| Shi et al, 201147 | Longitudinal | C30+BR23 | Chinese | 132 (77) | 2007–2008 | Before surgery | BCS: 50.3 (8.6), TM: 53.84 (10.2), TM-R: 47.7 (8.2) |

In situ, I–III | 5 |

| Ng et al, 201541 | Longitudinal | C30+BR233 | Chinese, Malay, Indian, other (Malaysia) |

221 | 2011–2015 | Newly diagnosed | 55.1 (11.5) | In situ, I–IV | 4 |

| Munshi et al, 201297 | Longitudinal | C30+BR23 | Indian | 188 | – | During radiotherapy | – | In situ, I–III | 3 |

| Damodar et al, 201337 | Longitudinal | C30+BR23 | Indian | 41 | 2011 | During chemotherapy | 46.1 (11.2) | – | 3 |

| Sultan et al, 201740 | Longitudinal | C30+BR23 | Indian | 25 (76) | 2014–2015 | Newly diagnosed | Mean 40 (range: 28–65) | I | 3 |

| So et al, 2014†51 | Cross-sectional | FACT-G | Chinese | 163 | 2010–2011 | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) years since diagnosis* | 51 (9.2) | In situ, I–IV | 3 |

| Wong and Fielding, 200756 | Longitudinal | FACT-G | Chinese | 249 (88) | – | – | 48.4 (11.9) | In situ, I–IV | 5 |

| Yan et al, 201643 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese | 1160 (64) | 2013 | 15.0 (6.7) years since diagnosis | 57.7 (11.5) | In situ, I–IV | 7 |

| Ohsumi et al, 200944 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Japanese | 93 (93) | 2004–2005 | 7 (5–11) years since surgery* | 58 (44–83) age at time of survey ᶣ | – | 6 |

| Park et al, 201142 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Korean | 1094 (88) | – | 73.4% were ≤3 years since surgery | 46.9 (8.8) | I–III | 5 |

| Park and Hwang, 201271 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Korean | 52 (94) | 2007–2008 | 1.7 (1.8) years since recurrence | 48.3 (8.3) age at recurrence | – | 5 |

| Thanarpan et al, 201598 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Thai | 127 | 2014–2014 | – | 51.9 (8.9) | In situ, I–III | 5 |

| He et al, 201263 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese | 180 (90) | 2000–2008 | BCT: 5 (1.3–8.5), TM: 5.4 (1.3–9.6) years since diagnosis* |

BCS: 44 (10), TM: 45 (9) |

I–II | 4 |

| Hong-Li et al, 201455 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese | 154 | 2008–2010 | Group 1: 1 year (n=64), group 2: 2 years (n=48), group 3: 5 years since diagnosis (n=42) | Group 1: 47.4 (8.8), group 2: 43.3 (10.3), group 3: 59.1 (9.4) | I–III | 4 |

| Chang et al, 200799 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese (Taiwan) | 235 (94) | – | 3 (1–12) years since diagnosis* | 49 (32–69)ᶣ | I–IV | 4 |

| Kim et al, 2013100 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Korean | 77 | – | – | 49.2 (7.7) | I–IV | 4 |

| So et al, 2013101† | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese | 279 (80) | 2007 | – | – | In situ, I–IV | 4 |

| Zou et al, 201475 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese | 156 (87) | – | – | 47.7 (10.3) | – | 4 |

| Jiao-Mei et al, 201574 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese | 93 | 2013–2013 | 5.6 (1.8) years since diagnosis | 51.76 (88.9) | I–IV | 4 |

| Qiu et al, 2016102 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese | 76 (76) | 2014 | 52.97 months since diagnosis | Mean 45.8 (range 23–76) age at time of survey | – | 4 |

| Shin and Park, 201757 | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Korean | 264 (94) | 2014 | 56.1% were ≤1 year, 32.6% 1–5 years, 11.4% ≥5 years since diagnosis | 4.2% were aged ≤39 years at time of survey, 29.9% 40–49, 53.8% 50%–59, 12.1% ≥60 | ?–III | 4 |

| So et al, 201145‡ | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese | 261 | 2006–2007 | During chemotherapy or radiotherapy | 21% were aged ≥60 | In situ, I–IV | 3 |

| Park and Yoon, 201352§ | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Korean | 200 | – | During chemotherapy | 45.6 (7.1) | I–IV | 3 |

| Pahlevan Sharif, 201776¶ | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese, Malay, Indian, other | 118 (93) | 2016 | 2.9 (1.9) years since diagnosis | 51.0 (9.4) | I–III | 3 |

| Sharif and Khanekharab, 201777¶ | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese, Malay, Indian, other | 130 | – | 3.0 (1.9) years since diagnosis | 51.2 (9.3) | I–III | 2 |

| So et al, 2009103‡ ** | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Chinese | 215 (75) | – | 5.5 (3) years since diagnosis | 51.65 (10.4) | I–IV | 4 |

| Pandey et al, 2005104†† | Cross-sectional | FACT-B | Indian | 504 (99) | – | – | 47.6 (11) | I–IV | 3 |

| Cao et al, 2016105 | Longitudinal | FACT-B | Chinese | 486 (92) | 2010–2013 | Start hormone therapy | 57.3 (range: 27–79) | – | 6 |

| Pandey et al, 200668 | Longitudinal | FACT-B | Indian | 254 (99) | 2002–2003 | Presurgery and postsurgery time points were used | 45.6 (10.6) | ?–IV | 5 |

| Taira et al, 201264 | Longitudinal | FACT-B | Japanese | 140 | 1998–2003 | Less than 6 weeks since surgery | 53 (24–77) | In situ, I–III | 5 |

| Gong et al, 201769 | Cross-sectional | C30+FACT G | Chinese | 3344 (65) | 2013 | 8.5 (6.5) years since diagnosis | 59.3 (7.9) age at time of survey | – | 5 |

*Median (IQR).

†Same sample population.

‡Same sample population.

§Max score of 6 for longitudinal studies, while 8 for cross-sectional studies.

¶Same sample population.

**Significance of associations not reported.

††Direction of association not reported.

BR23, EORTC-QLQ-BR23; BCS, breast-conserving surgery; C30, EORTC-QLQ-C30; TM, mastectomy; TM-R, mastectomy with reconstruction.

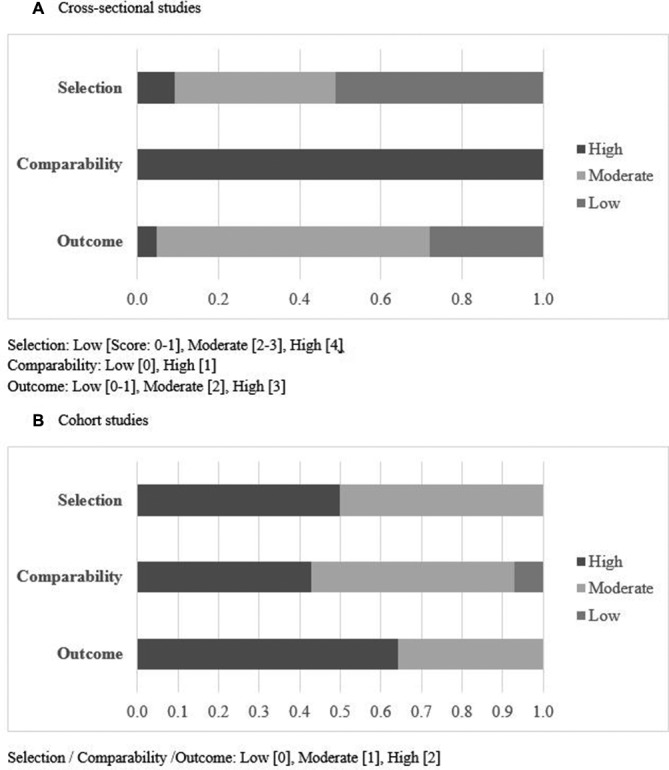

Quality assessment

Of the 43 studies with a cross-sectional design, none received the maximum score of the quality assessment (table 2). There were 22 articles with a low score for selection (score of 0–2) due to the use of convenience sampling and small (<300) sample size (online supplementary table 1). All cross-sectional studies described their study population, conferring a high score for comparability (figure 2). Reporting of outcome was an issue in cross-sectional studies: 20 studies did not report confidence intervals or standard errors and 27 had <70% response rate (online supplementary table 1). Nine of 14 longitudinal studies were of good quality having scores of 5–6 (max=6) (table 2). The remaining five studies of poorer quality with scores of 3 or 4, four did not have a representative sample of their target population,37–40 four had a follow-up of <70% but did not provide description of lost to follow-up and none controlled for additional determinants37–41 (online supplementary table 2).

Figure 2.

Quality assessment using the quality assessment scale for cross-sectional studies or an adapted version of Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies. Selection was based on the representativeness of the study population or cohort. Comparability and outcome were based on method of determining and reporting exposure of interest and outcome, respectively.

Most determinants studied were consistent in the direction of association or were not associated with global health status and/or general well-being (table 3). In studies on global health status, marital status, household income, type of surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormone therapy, conflicting results were found. Studies on general well-being, looking at time since diagnosis, age and unmet sexuality needs measured by short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS) also reported conflicting results. Table 4 presents a summary of determinants which were found to be associated with global health status and/or overall well-being.

Table 3.

Associations studied using EORTC-QLQ-C30/EORTC-QLQ-BR23 or FACT-G/FACT-B

| First author, year of publication | QoL outcomes | Determinant | Type of association with QoL outcomes |

| Studies using the EORTC-QLQ-C30 questionnaire | |||

| Cross-sectional (n=5) | |||

| Noh, 200872* | Global health status and social functioning | Involved in decision making | Positive |

| Reflection of own value to decision | |||

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and social functioning | Experience of treatment toxicity | Negative | |

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning and social functioning | Hospitalisation with treatment toxicity | Negative | |

| Global health status, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and social functioning | Problem obtaining surgery | Negative | |

| – | Having regular follow-up | – | |

| Akechi, 201070† | Global health status | Higher scores in the domains of SCNS: psychological, physical and daily living, sexuality, health system and information, care and support | Negative |

| Edib, 201648† | Global health status | Time since diagnosis (<2, 2–5 and >5 years) | Positive |

| Ethnicity (Malay vs Chinese vs Indian) | |||

| Higher household income (<RM2000, RM2000–RM4000 and >RM4000) | |||

| Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | |||

| Immune therapy (yes vs no) | |||

| Unmarried (Un) versus married (M) versus widowed/divorced (WD) | W/D<M < Un | ||

| Older age (≤40, 40–49 and ≥50) | Negative | ||

| Employed versus retired versus housewife | |||

| Higher stage (0, 1, 2, 3 and 4) | |||

| Radiotherapy (yes vs no) | |||

| Chemotherapy (yes vs no) | |||

| Hormone therapy (yes vs no) | |||

| Higher scores in SCNS – physical needs | |||

| Higher scores in SCNS – psychological needs | |||

| Higher scores in SCNS – care and support needs | |||

| – | SCNS – sexuality needs | – | |

| – | SCNS – health system and information needs | – | |

| Kim, 201291* | Role functioning | Higher bone density | Positive |

| Huang, 201750† | Global health status | Time since diagnosis (2–3, 3–5 and ≥5 years) | Positive |

| Higher household income (≤US$1000, US$1001–US$2000 and ≥US$2001) | |||

| Tumour stage | |||

| Comorbidities (0, 1, 2 and ≥3) | Negative | ||

| Treatment (combinations of surgery (S), chemotherapy (C), radiotherapy (R), hormone therapy (H), targeted therapy (T)) | C>S+C+H>S+C+R+H+T>S+C>others> S+R+ hour>S+C+R+ hour>S+C+R>S+H |

||

| – | Illness duration (ref: 2–3, 3–5 and ≥5 years) | 3–5 years>2–3 years | |

| – | Recurrence or metastasisation | – | |

| Liang, 201654† | Global health status | Year of diagnosis | Negative |

| Symptom distress | |||

| Global health status | Symptom management self-efficacy | Positive | |

| Longitudinal (n=2) | |||

| Jang, 201292† | – | Presence of religion | – |

| – | Higher religious activity (at 5 days and 1 year postsurgery) | – | |

| – | Higher intrinsic religiosity at 5 days postsurgery | – | |

| Global health status | Higher intrinsic religiosity at 1 year postsurgery | Positive | |

| Wani, 201239 | Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and social functioning | Time at first chemotherapy treatment, 6, 12 and 24 months after first visit | Positive |

| Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulty | Negative | ||

| Studies using the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and EORTC-QLQ-BR23 questionnaire | |||

| Cross-sectional (n=13) | |||

| Yusuf et al 201353 | Nausea and vomiting, dyspnoea, constipation and breast symptoms | Malay versus Chinese | Positive |

| Kim et al, 201561 | Role functioning, social functioning, body image and fatigue | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | Positive |

| Pain, insomnia and arm symptoms | Negative | ||

| Body image and fatigue | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy with reconstruction | Positive | |

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective | Better subjectively measured cosmesis | Positive | |

| Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea, systemic therapy side effects, breast symptoms, arm symptoms and hair loss | Negative | ||

| Body image | Objectively measured cosmesis (good vs poor) | Positive | |

| Body image and diarrhoea | Panel score for cosmesis (good vs poor) | Positive | |

| Chui et al, 201521 | – | Age (30–39, 40–49, 50–59 and ≥60)‡ | – |

| Global health status | Ethnicity (Malay vs Indian)‡ | Positive | |

| Ethnicity (Chinese vs Indian)‡ | |||

| Education (tertiary vs primary/lower)‡ | |||

| Education (secondary vs primary/lower)‡ | |||

| Household income (≤RM3000 vs >RM3000)‡ | |||

| Single versus ever married‡ | |||

| Chemotherapy (postponed vs on schedule)‡ | |||

| – | Stage (early vs late)‡ | – | |

| – | Chemotherapy cycles (2/3/4 vs 5/6)‡ | – | |

| – | Complementary and complementary medicine (MBP vs MBP-NP vs MBP-NP-TMed)‡ | – | |

| Financial difficulty, sexual enjoyment, systemic therapy side effects and breast symptoms | Complementary and complementary medicine (users vs non-users) | Positive | |

| Emotional functioning and cognitive functioning | Complementary and complementary medicine (single (S), dual (D), triple (T) modality) | S<T<D | |

| Body image and future perspective | S<D<T | ||

| Upset by hair loss | D<T<S | ||

| Systemic therapy side effects | T<D<S | ||

| Lee, 200767§ | Global health status | Presence of religion | Negative |

| Presence of one or more comorbidity | |||

| Incomplete versus completed treatment | |||

| Problems before surgery | |||

| Involved in decision making | Positive | ||

| Better perceived overall medical care | |||

| – | Time since diagnosis (≥5 years vs <5 years) | – | |

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, social functioning and sexual enjoyment | Treatment status: post versus ongoing versus non | Post > (Ongoing = Non) | |

| Fatigue, pain, insomnia, appetite loss and body image | Negative | ||

| Sun, 201462 | Emotional functioning, social functioning and body image | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy versus mastectomy with reconstruction | Positive |

| Nausea and vomiting, financial difficulty, arm symptoms (score for mastectomy with reconstruction was lower than for those with breast-conserving surgery) | Negative | ||

| Okamura, 200593 | Emotional functioning, body image and future perspective | Presence of psychiatric disorder | Negative |

| Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, appetite loss and diarrhoea | Positive | ||

| Huang, 201060 | Dyspnoea | Older age | Positive |

| Role functioning | Married (yes vs no) | Negative | |

| Breast symptoms | Positive | ||

| Global health status and role functioning | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | Negative | |

| Fatigue, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, breast symptoms and arm symptoms | Positive | ||

| Insomnia, breast symptoms and arm symptoms | Adjuvant therapy (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Insomnia | Hormone therapy (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Kang, 201222 | Arm symptoms | Use of complementary and complementary medicine | Positive |

| Park, 201258 | Sexual functioning and sexual enjoyment | Older age | Negative |

| – | Tumour size | – | |

| – | Lymph nodes involvement | – | |

| Global health status | Metastatic disease | Negative | |

| Physical functioning and role functioning | Positive | ||

| – | Postsurgery versus presurgery | – | |

| – | Axillary clearance | – | |

| Pain | Chemotherapy (yes vs no) | Negative | |

| Appetite loss, sexual enjoyment | Radiotherapy (yes vs no) | Negative | |

| Future perspective | Hormone therapy (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| – | Self-massage | – | |

| – | Lymphoedema duration | – | |

| Tang, 201673 | Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, body image and future perspective | Diabetes mellitus (yes vs no) | Negative |

| Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, constipation, diarrhoea, financial difficulty, systematic therapy side effects, breast symptoms, arm symptoms and upset with hair loss | Positive | ||

| Global health status, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning and constipation | Type 1 diabetes mellitus versus no diabetes mellitus | Negative | |

| Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, dyspnoea, insomnia, diarrhoea, systematic therapy side effects and breast symptoms | Positive | ||

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment, future perspective, fatigue and constipation | Type 2 diabetes mellitus versus no diabetes mellitus | Negative | |

| Body image, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, financial difficulty, systematic therapy side effects, breast symptoms, arm symptoms and upset with hair loss | Positive | ||

| Kang, 201794 | Global health status, physical functioning, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning, role functioning, body image and future perspective | Happiness status (Subjective Happiness Scale) | Positive |

| Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, financial difficulties, systemic therapy side effects, arm symptoms and upset with hair loss | Negative | ||

| Dubashi, 201059 | Global health status, sexual functioning and sexual enjoyment | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | Negative |

| Arm symptoms | Positive | ||

| Sexual functioning and sexual enjoyment | Having had ovarian ablation | Negative | |

| Shin, 201795 | Fatigue and pain | Higher levels of physical activity (metabolic equivalent-hours per week) (tertiles) | Negative |

| Sexual functioning | Positive | ||

| Physical functioning (only among stage I) | Positive | ||

| Chang, 201449¶ | Global health status | Education (more than high school vs less than middle school) | Positive |

| Married versus single/divorced/separated/widowed | |||

| Body image | Household income (>$3000 vs <$3000) | Positive | |

| Employed versus unemployed | Negative | ||

| – | Stage (1, 2, 3 and unknown) | – | |

| – | Being on active treatment | – | |

| Body image | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | Positive | |

| Sharma, 201796 | – | Time of radiotherapy (every day for 5 days) | – |

| Longitudinal (n=7) | |||

| Kao, 201546** | Global health status, emotional functioning, body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective | Older age (years) | Negative |

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective | Longer time since diagnosis (at 6 months/1 year/2 years vs at time of diagnosis) |

Positive | |

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective | Charlson comorbidity index | Negative | |

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective | Tumour stage (3/4 vs 0/1) | Negative | |

| Cognitive functioning and body image | Tumour stage (2 vs 0/1) | Negative | |

| Role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and body image | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | Positive | |

| Physical functioning, emotional functioning, body image, sexual functioning and sexual enjoyment | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy with reconstruction | Negative | |

| Global health status, physical functioning, emotional functioning, body image and future perspective | Chemotherapy (yes vs no) | Negative | |

| Global health status, emotional functioning, body image and future perspective | Radiotherapy (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Global health status, body image and future perspective | Hormone therapy (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, body image, sexual functioning and sexual enjoyment | Longer postoperative length of stay | Negative | |

| Munshi, 201038 | Social functioning and arm symptom | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy prior to radiotherapy | Negative |

| Sexual enjoyment and future perspective | Positive | ||

| Lee, 201178 | Diarrhoea | Longer time since diagnosis (1 year postdiagnosis vs at diagnosis) | Negative |

| Shi, 201147 | Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective | Longer time since diagnosis (2 vs 1 year) | Positive |

| Role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and body image | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | Positive | |

| Physical functioning, emotional functioning, sexual functioning and sexual enjoyment | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy with reconstruction | Negative | |

| Body image | Positive | ||

| Global health status | Older age | Negative | |

| Body image, sexual functioning and sexual enjoyment | Positive | ||

| Global health status, physical functioning, emotional functioning, body image and future perspective | Chemotherapy (yes vs no) | Negative | |

| Global health status, emotional functioning, body image and future perspective | Radiotherapy (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Global health status and body image | Hormone therapy (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective | Preoperative quality of life score | Positive | |

| Ng, 201541†† | Emotional functioning | At 6 months postdiagnosis versus at time of diagnosis | Positive |

| Physical functioning | Negative | ||

| Global health status, emotional functioning and social functioning | At 12 months postdiagnosis versus at time of diagnosis | Positive | |

| Munshi, 201297 | – | Radiotherapy using cobalt machine versus linear accelerator at completion of radiotherapy | – |

| Damodar, 201337 | Physical functioning, role functioning and future perspective | At ≥5 versus ≤2 cycles of chemotherapy | Negative |

| Fatigue, insomnia, arm symptoms and upset with hair loss | Positive | ||

| Sultan, 201740 | Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, sexual functioning, arm symptoms and breast symptoms | Chemotherapy (cycle ref: 1, 3, 6) | Negative |

| Fatigue, pain, dyspnoea, appetite loss, diarrhoea, sexual enjoyment and upset with hair loss | Positive | ||

| Studies using the FACT-G questionnaire | |||

| Cross-sectional (n=1) | |||

| So, 201451‡ | – | Age (years) | – |

| – | Time since diagnosis (months) | – | |

| – | Comorbidity (yes vs no) | – | |

| – | Education (no formal/primary vs secondary or higher) | – | |

| – | Employed versus unemployed/retired/homemaker | – | |

| – | Household income (≤HK$10 000, HK$10 001–HK$30000 and >HK$30 000) | – | |

| – | Married/cohabitation versus single/divorced/widowed | – | |

| – | Living alone (yes vs no) | – | |

| – | Family history (yes vs no) | – | |

| – | Stage (≤2 vs ≥3) | – | |

| – | Cancer is under control versus progression (yes vs no/unsure) | – | |

| – | Number of treatment received (one vs ≥2) | – | |

| Overall well-being | Hormone therapy (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Longer time needed to travel from home to hospital (minutes) | Negative | ||

| Higher scores in the domains of SCNS – psychological, physical and daily living, sexuality, health system and information, care and support | |||

| Longitudinal (n=1) | |||

| Wong, 200756‡‡ | Overall well-being, physical well-being and functional well-being | Longer time since diagnosis | Positive |

| Overall well-being and physical well-being | Positive mood | Positive | |

| Overall well-being and functional well-being | Higher levels of boredom | Negative | |

| Studies using the FACT-B questionnaire | |||

| Cross-sectional (n=15) | |||

| Yan, 201643 | Overall well-being, social well-being and functional well-being | Age (≤44, 45–54, 55–64 and ≥65 years) | Negative |

| Breast cancer subscale | Positive | ||

| Overall well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Primary school or less (L) versus middle/high school (M) versus college or more (C) | L<M<C | |

| Physical well-being | M<L<C | ||

| Social well-being | Married (Ma) versus single (S) versus widowed (W) versus divorced (D) | D<S<W<Ma | |

| Breast cancer subscale | Ma<D<W<S | ||

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Working in the public sector (G) versus private sector (P) versus farmers/unemployed (U) | U<P<G | |

| Social well-being | P<U<G | ||

| Breast cancer subscale | U<G<P | ||

| Overall well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Household income (<1000, 1001–3000, 3001–5000, >5000 RMB) | Positive | |

| Physical well-being | Generally positive | ||

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, functional well-being and breast cancer subscale | URBMI/NRCMS (UR) versus UEBMI health insurance (UE) versus undefined (Un) | UR<Un<UE | |

| Emotional well-being | UR<UE<Un | ||

| – | Stage (0/1, 2, 3, 4, unknown) | – | |

| – | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | – | |

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, emotional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Chemotherapy (yes vs no) | Negative | |

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Traditional Chinese medication (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Overall well-being, emotional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Time since diagnosis (<11.9 (A), 12–23.9 (B), ≥24 (C) months) | A<C<B | |

| Physical well-being, social well-being and functional well-being | A<B<C | ||

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Family harmony status (good vs not so good) | Positive | |

| Interaction with friends/neighbours (never, sometimes and frequent) | |||

| Overall well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Participation in healing club (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Breast cancer subscale | Negative | ||

| Overall well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Participation in peer-patient activities and communication | Positive | |

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Score on Perceived Social Support Scale (<50, 50–69 and ≥70) | Positive | |

| Ohsumi, 200944 | Overall well-being and social well-being | Older age (>60 vs ≤60 years) | Negative |

| – | Time since surgery (≥85 vs <85 months) | – | |

| Social well-being | Education (≥10 vs <10 years) | Positive | |

| – | Employed versus unemployed | – | |

| – | Household income (>10, 5–10 and ≤5 million yen) | – | |

| – | Married versus others | – | |

| – | Comorbidity (yes vs no) | – | |

| – | Lymph node status | – | |

| Breast cancer subscale | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | Positive | |

| – | Chemotherapy (yes vs no) | – | |

| – | Hormone therapy (yes vs no) | – | |

| Park, 201142 | Overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, functional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Older age (≥50 vs <50 years) | Negative |

| Park, 201271‡ | – | Age (≥50 vs <50 years) | – |

| – | Education | – | |

| – | Employment | – | |

| – | Economic status | – | |

| – | Single versus married | – | |

| – | Performance status | – | |

| – | Score in the domains of SCNS – health system and information, care and support | – | |

| Overall well-being | Higher score in the domains of SCNS – psychological, physical and daily living | Negative | |

| Higher score in the domains of SCNS – sexuality | Positive | ||

| Thanarpan, 201598 | Functional well-being | Better subjectively measured cosmesis | Negative |

| – | Objectively measured cosmesis | – | |

| – | Self-rated breast symmetry | – | |

| He, 201263 | Social well-being | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | Positive |

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Satisfaction with treatment | Not specified | |

| Chen, 201355 | Emotional well-being | Older age (≥40 versus <40 years) | Positive |

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, emotional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Time since treatment (1, 2 and 5 years) | Positive | |

| Social well-being | Can read and write versus illiterate | Positive | |

| Employed versus unemployed | |||

| Physical well-being, emotional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Higher stage | Negative | |

| – | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy versus mastectomy with reconstruction | – | |

| – | Chemotherapy (yes vs no) | – | |

| – | Radiotherapy (yes vs no) | – | |

| – | Hormone therapy (yes vs no) | – | |

| Chang, 200799§§ | – | – | – |

| Kim, 2013100 | Functional well-being | Oestrogen receptor status positive | Positive |

| So, 2013101 | Social well-being and functional well-being | Having social support | Positive |

| Breast cancer subscale | Negative | ||

| Zou, 201475†† | Overall well-being | Higher optimism | Positive |

| Affront copping mode versus give-in coping mode | |||

| Appraisal of illness (higher scores indicate more stress) | Negative | ||

| Having distress symptoms | |||

| Jiao-Mei, 201574 | – | Age (years) | – |

| – | Time since diagnosis (months) | – | |

| – | Stage | – | |

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Post-traumatic growth (low, moderate and high) | Positive | |

| Overall well-being and social well-being | Adverse childhood event (0, 1 and ≥2) | Negative | |

| Qiu, 2016102 | BRCA 1/2 carriers versus non-carriers | – | |

| Shin, 201757 | Age (≤39, 40–49, 50–59 and ≥60) | – | |

| Overall well-being | Education (middle school vs high school vs university) | Positive | |

| Employment (yes vs no) | Positive | ||

| – | Marital status (single vs married) | – | |

| – | Religion (yes vs no) | – | |

| – | Time since diagnosis (≤1, 1–5 and ≥5) | – | |

| Overall well-being | Recurrence (yes vs no) | Negative | |

| – | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy | ||

| – | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy with reconstruction | – | |

| Overall well-being | Empowerment | Positive | |

| – | Self-help group (yes versus no) | – | |

| So et al, 201145 | Overall well-being, physical well-being, emotional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Age (≥60 vs <60 years) | Positive |

| Park, 201352 | – | Age (≤39 vs 40 – 49 vs 50–59 years)‡‡ | – |

| Overall well-being | Household income (<2, 2–4, >4 million KRW/month)‡‡ | Positive | |

| Stage (1, 2, 3/4, unknown)‡‡ | Negative | ||

| – | Length of chemotherapy (<6, 6–12 and ≥12 months)‡‡ | – | |

| Overall well-being | Satisfaction with family support (unsatisfied, moderate and satisfied)‡‡ | Positive | |

| Frequency of sexual activity (none within 6 months, ≤3 in 6 months, 2–3 per month and ≥1 per week) | |||

| Overall well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Sexual function | Positive | |

| Overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Experienced menopausal symptoms | Negative | |

| Pahlevan Sharif, 201776 | Overall well-being, social well-being, functional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Higher external locus of control | Negative |

| Overall well-being and functional well-being | Higher internal locus of control | Positive | |

| Sharif, 201777 | Overall well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Higher score on powerful others | Negative |

| Overall well-being, social well-being and breast cancer subscale | Higher score on chance | Negative | |

| Breast cancer subscale | Avoidant emotional coping | Negative | |

| Overall well-being, social well-being and functional well-being | Active emotional coping | Positive | |

| Social well-being and functional well-being | Problem focused coping | Positive | |

| So, 2009103 | – | – | – |

| Pandey, 2005104 | – | – | – |

| Longitudinal (n=3) | |||

| Cao, 2016105 | Emotional well-being and social well-being | Age (>60 vs ≤60 years) | Positive |

| Longer time since enrolment (for most comparison between 6/12/18/24 months vs time since enrolment) | |||

| Mastectomy (yes vs no) | |||

| Prior chemotherapy (yes vs no) | |||

| Emotional well-being and social well-being | Axillary lymph node dissection (yes vs no) | Negative | |

| Pandey, 200668 | Overall well-being, physical well-being, functional well-being and breast cancer subscale | Postsurgery versus presurgery | Negative |

| Taira, 201264¶¶ | – | Concomitant disease (compared at 6, 12 and 24 months) | – |

| – | Nodal involvement (compared at 6, 12 and 24 months) | – | |

| – | Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy (compared at 6, 12 and 24 months) | – | |

| – | Intercostobrachial nerve perseverance (compared at 6, 12 and 24 months) | – | |

| Overall well-being and breast cancer subscale | Chemotherapy (yes vs no) (compared at 6 months) | Negative | |

| Breast cancer subscale | Chemotherapy (yes vs no) (compared at 12 and 24 months) | Negative | |

| – | Hormone therapy (compared at 6, 12 and 24 months) | – | |

| Study using both the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and FACT-G questionnaire | |||

| Cross-sectional (n=1) | |||

| Gong, 201769 | Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Exercisers versus non-exercisers | Positive |

| Nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea and appetite loss | Negative | ||

| Global health status, role functioning, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning, overall well-being, physical well-being and functional well-being | Frequency of exercise among exercisers (<5 vs ≥5 times a week) | Positive | |

| Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, dyspnoea, appetite loss and diarrhoea | Negative | ||

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, overall well-being, social well-being and functional well-being | Vegetable intake (≤250 vs >250 g/day) | Positive | |

| Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, dyspnoea, appetite loss, constipation and financial difficulty | Negative | ||

| Global health status, physical functioning, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning, overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Daily fruit intake (yes vs no) | Positive | |

| Dyspnoea, appetite loss and constipation | Negative | ||

| Global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being | Healthy behaviour (ref: 1 vs 0 vs 2 vs 3) | Positive | |

| Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation and financial difficulty | Negative | ||

Positive association implies an increase in measured score based on the respective scoring manual of each questionnaire. Global health status and functioning status of EORTC-QLQ-C30/-BR23: positive association implies better quality of life and functioning. Symptoms scales of EORTC-QLQ-C30/EORTC-QLQ-BR23: positive association implies higher level of symptoms. All scales of FACT-G/-B: positive association implies better well-being

*Domains studied: global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and social functioning.

†Domains studied: global health status.

‡Domains studied: overall well-being.

§Apart from determinant ‘treatment status’, domain studied: global health status.

¶Domains studied: global health status and body image.

**Domains studied: global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective.

††Domains studied: global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, body image, breast symptoms and arm symptoms.

‡‡Domains studied: overall well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, functional well-being.

§§Significance not mentioned (JT Chang).

¶¶Domains studied: overall well-being and breast cancer subscale.

MBP, mind–body practices; NP, natural products; NRCMS, New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme health insurance; SCNS, the short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey questionnaire; TMed, traditional medicine; UEBMI, Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance; URBMI, Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance.

Table 4.

Determinants associated with global health status and/or overall well-being

| Determinants studied | Better global health status (GHS)/overall well-being (OWB) | Poorer GHS/OWB | Others |

| Demographic | |||

| Time since diagnosis/surgery/ treatment/enrolment: GHS – CS: refs 48, 50 and 67 GHS – L: refs 41, 46, 47 and 78 OWB – CS: refs 43, 44, 51, 55, 74 and 95 OWB – L: refs 56 and 105 |

Longer time since diagnosis: GHS – CS: refs 39, 47, 48 and 50 GHS – L: ref 46 OWB – L: ref 56 12 months versus at time of diagnosis: GHS – L: ref 41 Longer time since treatment: OWB – CS: ref 55 |

– | Time since diagnosis (<11.9 months) < (≥24 months) < (12–23.9 months): OWB – CS: ref 43 |

| Ethnicity: GHS – CS: refs 21, 48 and 53 |

– | – | Malay<Chinese<Indian: GHS – CS: ref 48 Malay>Indian GHS – CS: ref 21 Chinese>Indian GHS – CS: ref 21 |

| Education: GHS – CS: refs 21 and 49 OWB – CS: refs 43, 44, 51, 55, 71 and 95 |

(Higher) Education: GHS – CS: refs 21 and 49 OWB – CS: ref 95 |

– | Primary school or less<middle/high school<college or more: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

| Year of diagnosis: GHS – CS: ref 54 |

– | Year of diagnosis: GHS – CS: ref 54 |

– |

| Older age: GHS – CS: refs 21, 48, 58 and 60 GHS – L: refs 46 and 47 OWB – CS: refs 42–45, 51, 52, 55, 71, 74 and 95 OWB – L: ref 105 |

– | Older age: GHS – CS: ref 48 GHS – L: refs 46 and 47 OWB – CS: refs 42–45 |

– |

| Employment: GHS – CS: refs 48 and 49 OWB – CS: refs 43, 44, 51, 55, 71 and 95 |

Employed (yes): OWB – CS: ref 95 |

– | Employed>retired>housewife: GHS – CS: ref 48 Working in public sector>private sector>farmers/unemployed: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

| Income: GHS – CS: refs 21 and 48–50 OWB – CS: refs 43 and 52 |

(Higher) Income: GHS – CS: refs 48 and 50 OWB – CS: refs 43 and 52 |

(Higher) Income: GHS – CS: ref 21 |

– |

| Marital status: GHS – CS: refs 21, 48, 49 and 60 OWB – CS: refs 43, 44, 51, 71 and 95 |

– | – | Widowed/divorced<married<unmarried GHS – CS: ref 48 Single<married GHS – CS: ref 21 Married<single/ divorced/separated/widowed: GHS – CS: ref 49 |

| Religion: GHS – CS: ref 67 GHS – L: ref 92 OWB – CS: ref 95 |

Presence of religion: GHS – CS: ref 67 Higher intrinsic religiosity at 1 year postsurgery GHS – L: ref 92 |

– | – |

| Comorbidity: GHS – CS: refs 50, 67 and 73 GHS – L: ref 46 OWB – CS: refs 44 and 51 OWB – L: ref 64 |

– | Comorbidity (yes): GHS – CS: refs 50 and 67 Diabetes mellitus (yes): GHS – CS: ref 73 (Higher) Charlson comorbidity index: GHS – L: ref 46 |

GHS – CS: Type 1 <no diabetes mellitus: GHS – CS: ref 73 Type 2 <no diabetes mellitus: GHS – CS: ref 73 |

| Clinical | |||

| Tumour stage: GHS – CS: refs 21, 48–50 and 58 GHS – L: ref 46 OWB – CS: refs 43, 51, 52, 55 and 74 |

– | (Higher) stage: GHS – CS: refs 48 and 50: OWB – CS: ref 52 Metastatic disease: GHS – CS: ref 58 Stage 3/4 versus 0/1: GHS – L: ref 46 |

– |

| Recurrence: GHS – CS: ref 50 OWB – CS: ref 95 |

– | Recurrence (yes): OWB – CS: ref 95 |

– |

| Treatment | |||

| (Type of surgery) BCS versus TM: GHS – CS: refs 48, 49 and 59–61 GHS – L: refs 38, 46 and 47 OWB – CS: refs 43, 44 and 63 OWB – L: ref 64 BCS versus mastectomy with reconstruction (TM-R): GHS – CS: refs 47 and 61 OWB – CS: ref 95 BCS versus TM versus TM-R GHS – CS: ref 62 OWB – CS: ref 55 TM (yes): OWB – L: ref 105 |

– | – | BCS>TM: GHS – CS: refs 48, 59 and 60 |

| Chemotherapy GHS – CS: refs 21, 48 and 58 GHS – L: refs 37, 40, 46 and 47 OWB – CS: refs 43, 44, 52 and 55 OWB – L: refs 64 and 105 |

– | Chemotherapy (yes): GHS – CS: ref 48 GHS – L: refs 46 and 47 OWB – CS: ref 43 |

Chemotherapy on schedule<postponed: GHS – CS: ref 21 At cycle 1>3>6: GHS – L: ref 40 Chemotherapy (yes)<no (compared at 6 months) OWB – L: ref 64 |

| Radiotherapy: GHS – CS: refs 48, 58 and 96 GHS – L: refs 46, 47 and 97 OWB – CS: ref 55 |

Radiotherapy (yes): GHS – L: refs 46 and 47 |

Radiotherapy (yes): GHS – CS: ref 48 |

– |

| Hormone therapy: GHS – CS: refs 48 and 58 GHS – L: refs 46 and 47 OWB – CS: refs 44, 51 and 55 OWB – L: ref 64 |

Hormone therapy (yes): GHS – L: refs 46 and 47 OWB – CS: ref 51 |

Hormone therapy (yes) GHS – CS: ref 48 |

– |

| Immune therapy: GHS – CS: ref 48 |

Immune therapy (yes): GHS – CS: ref 48 |

– | – |

| Treatment combination: (surgery (S), chemotherapy (C), radiotherapy (R), hormone therapy (H), targeted therapy (T)): GHS – CS: ref 50 |

– | – | C>S+C+H > S+C+R+H+T>S+C>others>S+R+ hour>S+C+R+ hour>S+C+R > S+H: GHS – CS: ref 50 |

| Treatment status: GHS – CS: refs 49 and 67 |

– | Treatment status (incomplete): GHS – CS: ref 67 |

Post-treatment>ongoing treatment=non-treatment: GHS – CS: ref 67 |

| Lifestyle | |||

| Exercise: GHS – CS: refs 69 and 95 OWB – CS: ref 69 |

Exerciser (yes): GHS and OWB – CS: ref 69 (Higher) Frequency of exercise: GHS and OWB – CS: ref 69 |

– | – |

| Diet: GHS and OWB – CS: ref 69 |

(Higher) Vegetable intake: GHS and OWB – CS: ref 69 Daily fruit intake (yes): GHS and OWB – CS: ref 69 |

– | – |

| Healthy behaviour: GHS and OWB – CS: ref 69 |

(More) Healthy behaviour: GHS and OWB – CS: ref 69 |

– | – |

| Unmet needs | |||

|

Short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS) – psychological, physical and daily living, sexuality, health system and information, care and support: GHS – CS: refs 48 and 70 OWB – CS: refs 51 and 71 |

(Higher) Scores for sexuality: OWB – CS: ref 71 |

(Higher) Scores in all domains: GHS – CS: ref 70 OWB – CS: ref 51 (Higher) Scores for psychological, physical and daily living: GHS – CS: ref 48 OWB – CS: ref 71 (Higher) Scores for care and support: GHS – CS: ref 48 |

|

| Others | |||

| Complementary and complementary medicine: GHS – CS: refs 21, 22 and 58 OWB – CS: ref 43 |

Traditional Chinese medication (yes): OWB – CS: ref 43 |

– | – |

| Cosmetic appearance: GHS – CS: ref 61 OWB – CS: ref 98 |

(Better) Subjectively measured cosmetic appearance: GHS – CS: ref 61 |

– | – |

| Symptom distress: GHS – CS: ref 54 OWB – CS: ref 75 |

– | Symptom distress: GHS – CS: ref 54 OWB – CS: ref 75 |

– |

| Involvement in decision making: GHS – CS: refs 67 and 72 |

Involvement in decision making (yes): GHS – CS: refs 67 and 72 |

– | – |

| Reflection of own value to decision: GHS – CS: ref 72 |

Reflection of own value to decision (yes): GHS – CS: ref 72 |

– | – |

| Problem obtaining surgery: GHS – CS: ref 72 |

– | Problem obtaining surgery (yes): GHS – CS: ref 72 |

– |

| Problems before surgery: GHS – CS: ref 67 |

– | Problems before surgery (yes): GHS – CS: ref 67 |

– |

| Experience of treatment toxicity: GHS – CS: ref 72 |

– | Experience of treatment toxicity (yes): GHS – CS: ref 72 |

– |

| Hospitalisation with treatment toxicity: GHS – CS: ref 72 |

– | Hospitalisation with treatment toxicity (yes): GHS – CS: ref 72 |

– |

| Time needed to travel from home to hospital: OWB – CS: ref 51 |

– | (Longer) Time needed to travel from home to hospital: OWB – CS: ref 51 |

– |

| Perceived overall medical care: GHS – CS: ref 67 |

(Better) Perceived overall medical care: GHS – CS: ref 67 |

– | – |

| Preoperative quality of life score: GHS – L: ref 47 |

(Higher) Preoperative quality of life score: GHS – L: ref 47 |

– | – |

| Sexual activity/function: OWB – CS: ref 52 |

(Higher) Frequency of sexual activity: OWB – CS: ref 52 (Higher) Sexual function: OWB – CS: ref 52 |

– | – |

| Experiencing menopausal symptoms: OWB – CS: ref 52 |

– | Experiencing menopausal symptoms: OWB – CS: ref 52 |

– |

| Symptom management self-efficacy: GHS – CS: ref 54 |

Symptom management self-efficacy: GHS – CS: ref 54 |

– | – |

| Insurance: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

– | – | URBMI/NRCMS<UEBMI health insurance<undefined: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

| Optimism: OWB – CS: ref 75 |

(Higher) Optimism: OWB – CS: ref 75 |

– | |

| Positive mood: OWB – L: ref 56 |

Positive mood: OWB – L: ref 56 |

– | – |

| Boredom: OWB – L: ref 56 |

– | (Higher) Levels of boredom: OWB – L: ref 56 |

– |

| Appraisal of illness: OWB – CS: ref 75 |

– | (Higher) Scores for appraisal of illness (ie, more stress): OWB – CS: ref 75 |

|

| Post-traumatic growth: OWB – CS: ref 74 |

(Higher) Post-traumatic growth: OWB – CS: ref 74 |

– | – |

| Adverse childhood event: OWB – CS: ref 74 |

– | More adverse childhood event: OWB – CS: ref 74 |

– |

| Locus of control: OWB – CS: ref 76 |

(Higher) Internal locus of control: OWB – CS: ref 76 |

(Higher) External locus of control: OWB – CS: ref 76 (Higher) Score on powerful others: OWB – CS: ref 77 (Higher) Score on chance: OWB – CS: ref 77 |

– |

| Coping mode: OWB – CS: refs 75 and 77 |

Active emotional coping: OWB – CS: ref 77 |

– | Affront coping mode>give in coping mode: OWB – CS: ref 75 |

| Empowerment: OWB – CS: ref 95 |

Empowerment (yes): OWB – CS: ref 95 |

– | – |

| Family harmony status: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

(Good) family harmony status: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

– | – |

| Interaction with friends/neighbours: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

Interaction with friends/neighbours: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

– | – |

| Participation in healing club: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

Participation in healing club: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

– | – |

| Participation in peer-patient activities and communication: OWB – CS: ref 43: |

Participation in peer-patient activities and communication: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

– | – |

| Social support: OWB – CS: refs 43 and 101 |

(Higher) Score on Perceived Social Support Scale: OWB – CS: ref 43 |

– | – |

| Satisfaction with family support: OWB – CS: ref 52 |

Satisfaction with family support: OWB – CS: ref 52 |

– | – |

BCS, breast-conserving surgery; CS, cross-sectional study; L, longitudinal study; NRCMS, New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme health insurance; TM, mastectomy; UEBMI, Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance; URBMI, Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance.

Age

Park et al found that patients with breast cancer who were of older age had poorer overall well-being and that older age was associated with longer time since surgery.42 In patients who were at least 5-year postdiagnosis, older age was associated with poorer overall well-being in those.43 44 In patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy, So et al observed that older age was associated with better overall well-being than those aged below 60 years.45 Apart from the study by So et al,45 other studies21 46–48 on this association showed that older age was associated with poorer global health status.

Marital status

Chui et al 21 and Edib et al 48 found that women who were single (as compared with ever married) and unmarried (as compared with currently married and widowed/divorced), respectively, had better global health status. However, Chang et al found that being married as compared with being single/divorced/widowed was associated with better global health status.49 The classification of widowed/divorced, which confers poorer HRQL than married, may have contributed to the difference in findings of Chui et al 21 and Chang et al,49 in addition the proportion of women who were never married (single) is small in both populations (11% unmarried and 17% unmarried/divorced/widowed, respectively).

Income

Edib et al 48 and Huang et al 50 found that higher household income was associated with better global health status, while Chui et al 21 found the opposite. While some reported higher household income to be also associated with better overall well-being, others did not find evidence of associations.44 51 Standard of living for the population is different among the different studies, making it difficult to access if the association seen was a result of the choice of categorisation of household income. Among the six studies21 43 48–50 52 that assessed household income, Chui et al were the only ones who looked at the effect of household income during treatment, in particular during chemotherapy, and found that higher income was associated with poorer global health status.21 Lower income might have been less of a concern in Malaysia, where lower income patients have access to welfare assistance, while patients of higher income are not eligible for. In addition, Edib et al studied survivors in the post-treatment period in Malaysia and found that higher household income was associated with better global health status.48

Other demographic determinants

Shorter time since breast cancer diagnosis,39 41 46–48 50 being of Chinese or Indian ethnicity as compared with Malay ethnicity,21 48 53 lower educational level21 49 and being diagnosed at later calendar year54 were associated with poorer global health status. Shorter time since diagnosis of breast cancer43 55 56 and lower educational level43 57 were associated with poorer overall well-being.

Tumour characteristics

Advanced stage disease was associated with poorer global health status46 48 50 58 and poorer overall well-being.52

Type of surgery

Edib et al observed that women who underwent breast-conserving surgery had better global health status than women who had mastectomy.48 However, Dubashi et al 59 and Huang et al 60 found that patients who had breast-conserving surgery had poorer global health status than those who had mastectomy. This could be due to the higher levels of, pain, breast symptoms and arm symptoms experienced by patients who had breast-conserving surgery as compared with those who had mastectomy.59 60 Furthermore, other studies comparing breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy did not find associations with global health status46 47 61 62 or overall well-being.43 44 55 57 63 64

Radiotherapy

Kao et al 46 and Shi et al 47 found that at 2 years postdiagnosis, women who have had radiotherapy had better global health status as compared with those who did were not treated with radiotherapy; however, Edib et al 48 found contrary results. After adjusting for potential confounders, the association between radiotherapy with poorer global health status was no longer significant.48 Park et al 58 and Hong-Li et al 55 did not find association between having had radiotherapy and global health status or overall well-being.

Hormone therapy

Edib et al 48 found hormone therapy was associated with poorer global health status; however, Kao et al 46 and Shi et al 47 found the opposite. Kao et al 46 and Shi et al 47 obtained information on hormone therapy from medical records. Using the classification of ever or current user of hormone therapy may result in misclassifying those who had discontinued with those on active therapy. Furthermore, patients who suffer adverse events, like hot flushes, are more likely to discontinue hormone therapy, which may result in patients who are on hormone therapy to be incorrectly perceived as having better global health status.65 66 In other studies, hormone therapy was not associated with global health status58 or overall well-being.44 55 64

Other treatment determinants

Ongoing treatment (vs completed treatment),67 having received chemotherapy46 48 or not having delayed chemotherapy21 39 were associated with poorer global health status. Recent (≤30 days) postsurgery (vs presurgery)68 and having received chemotherapy43 64 were associated with poorer overall well-being.

Complementary and alternative medication

The use of complementary and alternative medication in general, including dietary supplements, prayer, exercise and/or self-help techniques, was not associated with overall well-being.21 22 However, the use of traditional Chinese medication,43 empowerment of patients with breast cancer57 and participating in self-help groups57 were independently was associated with better overall well-being.

Lifestyle

Gong et al found that patients who had less healthy behaviour (comparing zero healthy behaviour, 2, or 3 to 1) had lower global health status and overall well-being.69 Patients with breast cancer who did not exercise (vs exercise) or with lower frequency of exercising (vs ≥5 times a week) had lower global health status and overall well-being.69 Furthermore, those who had low vegetable (vs >250 g per day) intake and did not eat fruits daily had lower global health status and overall well-being.69

Unmet needs

Having more unmet needs, especially in the physical and daily living, were associated with poorer global health status48 70 and poorer overall well-being.44 51 So et al 51 found that women who had unmet sexuality needs (measured by SCNS) had poorer overall well-being, while Park et al 71 reported the opposite. Park et al found that higher needs was associated with better overall well-being in 52 women who experienced recurrence of breast cancer, citing that patients who have better sexual functioning are more likely to have more sexuality needs.71 Akechi et al 70 found that unmet sexuality need was associated with poorer global health status, while Edib et al 48 did not find such association.

Others

Lack of involvement in decision making,67 72 lower self-efficacy in symptom management,54 poorer perceived overall medical care67 and having higher Charlson comorbidity index or comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension and arthritis,46 50 73 were associated with poorer global health status. Adopting a give-in coping mode or believing that they are not in control,74–77 lower perceived social support and lower self-efficiency43 52 57 and poorer perceived overall medical care43 were associated with poorer overall well-being.

Differences in quality of life between patients with breast cancer patients and general population

Two studies both conducted in Korea studied differences in global health status between patients with breast cancer and the general population.67 78 Lee et al found that global health status was not different among patients who had completed treatment for recurrent breast cancer as compared with the general population.67 However, role functioning, cognitive functioning and social functioning were lower, and fatigue levels and financial difficulties were higher in patients treated for recurrence as compared with the general population.67 Lee et al compared patients with breast cancer to the general population at two time points, immediately after diagnosis and 1 year after diagnosis and found that the general population had higher global health status at both time points.78

Discussion

In Asia, patients with breast cancer have poorer HRQL than the general population. Patients with comorbidities, with chemotherapy, lower social support and with more unmet needs have poorer quality of life. However, HRQL improves with time since diagnosis and having healthier behaviour is associated with better HRQL. Within and across the scope of each questionnaire, most associations with poor global health status or overall well-being were concordant. Discordant results in studies were found in the associations of age, marital status, household income, type of surgery, radiotherapy and hormone therapy, and unmet sexuality needs with global health status or overall well-being.

Patients with one or more comorbidities during the time of survey had poorer HRQL. Comorbidity occurs in 20%–30% of patients with breast cancer.79 Comorbidities may be pre-existence or developed after diagnosis; hypertension, arthritis and diabetes are common to patients with breast cancer.14 Studies outside Asia showed similar results; having less co-morbidity was also found to be associated with better HRQL in African-American and Latina breast cancer survivors.80 81 Having pre-existing diabetes was associated with poorer HRQL, in patients with early breast cancer in the USA.82 In addition, patients with pre-existing comorbidities are more likely to have treatment complications, which may lead to poorer HRQL.79

In Asian patients with breast cancer, of all treatments studied, only being on or received chemotherapy was clearly associated with poorer HRQL. This is in agreement with Wöckel et al, who found that patients who received chemotherapy had decreased HRQL, and it was more likely to remain low.83 However, patients on chemotherapy are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced stage disease which was also found to be associated with HRQL. Other treatments, like surgery, are less likely to be associated with advance stage disease, and may be the reason for the null findings. Furthermore, patients with poorer prognosis or who are undergoing chemotherapy are more likely to experience pain, fatigue and potentially other adverse events.84 85

The lack of social support and higher unmet needs were associated with poorer HRQL, in Asian countries. Having a large percentage of unmet needs is not unique to Asia.86 87 Provision of social support should be in-line with the needs of the patient, so as to not adversely impact their HRQL.88 89 In this review, social support, in areas that enable patients to be empowered with higher self-efficacy, was associated with better HRQL. The provision for the educational needs or having access to the service of a breast care nurse may help in reducing unmet needs and provide social support from an institutional effort.89 90

We acknowledge that this systematic review has some limitation. The studies included had varying patient selection criteria, which may be the reason for discordance results in certain determinants. Studies conducted in patients during the treatment period would differ from those conducted after completion of treatment. The choice of statistical analysis varies, with most reporting associations from linear models and some from correlation analysis; thus, we were not able to provide a sense of the level of association. Non-standard methods of measuring determinants were used in some studies, limiting the comparability of the studies. Furthermore, we cannot determine the direction of association from cross-sectional studies; it is possible that some determinant, such as unmet needs and use of CAM, were the result of poorer HRQL. While most of the studies of longitudinal design were of high quality, the majority of the cross-sectional design studies were of moderate or poor quality. Future cross-sectional studies should consider reporting reasons for non-response and include multiple sites if sample size is insufficient.

Conclusion

Patients with breast cancer in Asia have a poorer HRQL than the general population. A shorter time since diagnosis of breast cancer,39 41 43 46–48 50 55 56 having a Chinese or Indian ethnic background as compared with Malay ethnicity,21 48 53 lower educational level21 43 49 57 and advanced stage breast cancer disease46 48 50 52 58 were associated with poorer HRQL. There is some evidence that patients with comorbidities or with chemotherapy are more likely to experience poorer HRQL. The lack of social support and having unmet needs may predict poorer HRQL. Further studies into methods to provide social support in the Asian setting is needed to identify effective ways to improve patients’ HRQL.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HMV, PJH and SAMG designed the study. PJH and SAMG performed the systematic review. PJH wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed and revised the manuscript.

Funding: The study was carried out with the support from the National University Hospital, Singapore, Clinician Scientist Award, National Medical Research Council R-608-000-093-511 and Asian Breast Cancer Research Fund N-176-000-023-091 awarded to MH.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No dataset was used in this systematic review.

References

- 1. Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Yip CH, et al. . Incidence and mortality of female breast cancer in the Asia-Pacific region. Cancer Biol Med 2014;11:101–15. 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]