Abstract

Introduction

The proportion of older acute care physicians (ACPs) has been steadily increasing. Ageing is associated with physiological changes and prospective research investigating how such age-related physiological changes affect clinical performance, including crisis resource management (CRM) skills, is lacking. There is a gap in the literature on whether physician’s age influences baseline CRM performance and also learning from simulation. We aim to investigate whether ageing is associated with baseline CRM skills of ACPs (emergency, critical care and anaesthesia) using simulated crisis scenarios and to assess whether ageing influences learning from simulation-based education.

Methods and analysis

This is a prospective cohort multicentre study recruiting ACPs from the Universities of Toronto and Ottawa, Canada. Each participant will manage an advanced cardiovascular life support crisis-simulated scenario (pretest) and then be debriefed on their CRM skills. They will then manage another simulated crisis scenario (immediate post-test). Three months after, participants will return to manage a third simulated crisis scenario (retention post-test). The relationship between biological age and chronological age will be assessed by measuring the participants CRM skills and their ability to learn from high-fidelity simulation.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol was approved by Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board (REB Number 140–2015) and the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (#20150173–01H). The results will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed journal and at scientific meetings.

Trial registration number

Keywords: adult anaesthesia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Acute care physicians are recruited from various institutions across Ontario from three specialties.

Participants are immediately debriefed by experts on their crisis resource management performance.

Simulation environment for each scenario is tailored to the participant’s specialty.

Ageing physicians likely did not train with mannequin-based simulation compared with physicians who recently completed their certification.

Introduction

The proportion of older acute care physicians (ACPs) has been steadily increasing.1 Within Canada, approximately 32%–40% of anaesthesiologists and emergency and critical care physicians are over the age of 55 years. A survey of members of the American Society of Anesthesiologists in 2013 revealed that a greater percentage of members are older (>55 years) in 2013 compared with 2007.2 The shift in workforce demographics may be explained by several factors such as the recent economic crisis, which has forced some physicians to choose to delay retirement. Furthermore, the reduction in the number of residency positions in the early 1990s led to a smaller proportion of middle-aged ACPs.3 4 Thus, with an overall shortage of healthcare providers, this has led to a greater proportion of older ACPs delaying retirement in order to meet the demands of the healthcare system.

Acute care specialties such as critical care, emergency medicine and anaesthesiology require providers to excel at both technical and non-technical skills (eg, teamwork, communication and leadership) and function at a high cognitive level in a fast-paced environment that requires quick decision making and problem solving. Ageing is associated with physiological changes which, in turn, can influence both a physician’s clinical and decision-making abilities. The time required for processing information is prolonged, and decision making can be compromised in physicians as they age.5–8 Physiological stress impacts the ageing physician to a great extent (compared with their younger cohort) with potential consequences on performance. The prevalence of stress, illness, fatigue and dementia increases as one ages.3 5–7 9 Manual dexterity can also be affected with the onset of arthritis and alterations in visual acuity.3 10 Siu and colleagues found that anesthesiologist’s age and years from residency were associated with decreased simulated cricothyroidotomy proficiency.5 11

Research investigating how such ageing-related physiological changes affect clinical performance and patient safety is limited.10 12 The common idea that ageing physicians compensate through experience and pattern recognition from previous similar clinical situations8 11 has been called into question. First, physiological studies have shown that neural compensation mechanisms to ageing are limited and cannot prevent a certain amount of cognitive decline in the long term.13Second, Duclos et al found that older surgeons had an increased rate of patient complications after thyroid surgery.14 In addition, 10 years of litigation data show that anesthesiologists in British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec who are older than 65 have 1.5 times the risk of being involved in litigation compared with those aged less than 51 years, with the settlements being generally larger.10 11 For all specialties, disciplinary incidents involving physicians are likely to occur later in practice, increasing with each 10-year interval since first getting a licence.8 12 15 Moreover, the degree of injury identified in the claims of physicians 65 years of age or older was of greater severity.8 Lastly, studies have shown that long-term medical knowledge retention can be negatively impacted with increasing age as well.16 Overall, human physiology, previous investigations, litigation, disciplinary and critical event data strongly suggest that ageing effects among physicians are not compensated by greater experience as previously thought.

Crisis resource management (CRM) skills are essential clinical skills within acute care specialties and are vital for patient safety. CRM encompasses technical skills (eg, defibrillation, drug preparation and intubation), as well as a rapid and structured approach to non-technical, cognitive skills such as decision making, task management, situational awareness and team management. CRM skills are crucial during life-threatening crises and are precisely the type of processing and decision-making skills that may decline as one ages, thus contributing to patient safety concerns described above.

Evidence shows that high-fidelity simulation-based education is effective for learning CRM, transferring skills to the clinical setting and improving patient outcomes.17 However, the effectiveness of simulation-based education for teaching CRM has mainly focused on undergraduate and postgraduate learners, whereas limited data are available for the ageing physician population.18 Despite the limited evidence to support claims that simulation for continuing professional development actually improves learning,19 simulation-based education has been recommended as a tool to train and assess ACPs.10 20 Thus, there is a need to investigate if physicians’ age influences baseline CRM performance or learning from simulation-based education.

Methods and analysis

Aim

Our research aims are to investigate whether ageing impacts CRM skills in ACPs and to determine whether ageing influences CRM skill learning from high-fidelity simulation and debriefing.

We hypothesise that ACPs’ baseline CRM performance as assessed using high-fidelity, simulation-based scenarios decline as physician age increase. Our secondary hypothesis is that although ACPs’ CRM performance will increase immediately following simulation-based practice scenarios with feedback, increasing physician age will negatively impact the retention of CRM skills.

Design

This study is a prospective cohort multicentre interventional study. This study has been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02683447), and this manuscript follows the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials reporting guidelines.21

Ethics

This study will recruit from two large university-affiliated tertiary centres in Toronto and Ottawa, Canada. Written informed consent and a confidentiality agreement will be obtained from all participants by a trained research assistant or a study investigator. ACPs from the academic affiliated sites of both universities will be approached for recruitment, with data collection being conducted locally in each centre. Throughout the study and on completion of the study, all data will be stored on secure servers at each sites institution. Data will be transferred using secure, encrypted, protected file transfer software.

Participant characteristics

All practising emergency, critical care and anaesthesia staff with a minimum of 5 years of clinical practice postcertification will be approached for participation. Participants will not be scheduled for a study session on a postcall day. Participants will receive email advertisements for voluntary participation in the study, and all eligible physicians will be recruited from both academic and community sites. In Toronto, a formal simulation training curriculum for faculty does not exist. In Ottawa, a curriculum is in development and is in its infancy when it comes to implementation.

Simulation scenario development

The core concepts pertaining to CRM skills and subsequent management of pulseless electrical activity (PEA) arrest will be consolidated into one document by the principal investigators (FA and SB) and then sent out to three faculty ACPs (one from each specialty involved) from universities not involved in the recruitment, who are trained advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) instructors, for review and revisions. Once core concepts are agreed on, the three simulation scenarios will be developed. The simulation environment for each scenario will be tailored to their respective specialty (ie, intensive care unit, operating room and emergency room). Each scenario will be adapted in terms of environment (layout/equipment) and appropriate background noise (overhead announcements and monitor noise) for the participant’s specialty to ensure psychological and environmental/technical fidelity. Each scenario will then be piloted before recruitment to ensure an equal degree of difficulty and appropriate fidelity.

Data collection

Research personnel at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre will generate computer-based randomisation of scenarios for all participants. Study participants will be blinded to their randomisation assignment and unblinding will not occur. The simulation environment for each scenario will be tailored to their respective specialty (ie, intensive care unit, operating room and emergency room). Scenarios will be designed by an interdisciplinary group and will be piloted before recruitment to ensure an equal degree of difficulty. It will consist of a unique inciting event and will result in PEA arrests.

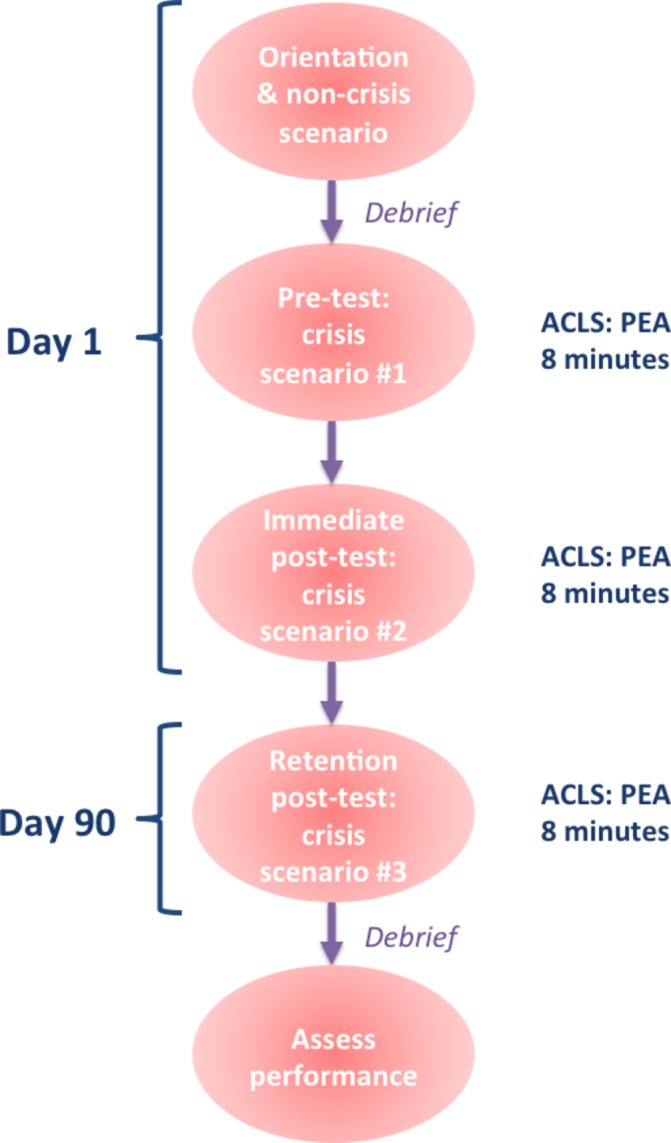

An overview of the study visits for all participants are shown in figure 1, and detailed assessments for each visit are listed in table 1. On day one, participants will complete a demographic questionnaire to quantify potential confounding factors, such as previous simulation, ACLS and crisis management experience and a life expectancy questionnaire online to determine the subject’s biological versus chronological age (www.projectbiglife.ca). Depending on certain lifestyle factors, a person might have a ‘younger or older’ biological age when compared with their stated chronological age.22 Next, a standardised structured orientation session will be held for each participant, including a non-crisis-simulated scenario for familiarisation with the simulation environment/equipment in which the study scenarios will take place. The scenario will be an induction of general anaesthesia using rapid sequence induction (a common technique performed by all three acute care specialties in this study).

Figure 1.

An overview of study visits for participants consented and randomised to this study. ACLS, advanced cardiovascular life support; PEA, pulseless electrical activity.

Table 1.

Study visits

| Visit −1 | Visit 0 | Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | |

| Enrolment | |||||

| Eligibility screen | X | ||||

| Informed consent | X | ||||

| Allocation | X | ||||

| Interventions | |||||

| Demographic questionnaire | X | ||||

| Life expectancy questionnaire | X | ||||

| Orientation and non-crisis scenario | X | ||||

| Pretest | X | ||||

| Debrief * | X | X | |||

| Immediate post-test | X | ||||

| Retention post-test | X | ||||

| Assessments | |||||

| Ottawa Global Rating Scale† | X | ||||

| Advance cardiac life support checklist† | X | ||||

*To be performed by experienced debriefers.

†To be performed by two independent raters.

Participants will manage three distinct scenarios for this study. All three scenarios will be matched for difficulty. The first will be a PEA arrest scenario (pretest), followed by a 20 min facilitator-led debrief on their CRM performance. They will then manage another PEA crisis scenario (immediate post-test). Three months later, participants will return and manage a third PEA arrest scenario (retention post-test) in addition to a questionnaire to assess whether they have recently completed ACLS training. The retention post-test can be completed starting at 3 months (up to 6 months) following the initial pretest. These scenarios will all be video-recorded, and all data will be stored on encrypted devices in compliance with local privacy policies at each institution. Following a prewritten standard script, confederates (trained actors with healthcare backgrounds) will serve as a respiratory technician and nurse to be directed by the participant, but they will not provide tips or guidance in terms of how to manage the crisis. Two raters who have not worked with the participants, blinded to the study hypotheses and test phase will evaluate the participant’s performance using validated assessment tools stated below.

Debrief

All facilitators will be experienced in debrief and CRM training. Despite this, the facilitators will be trained on the outcome measures and will have the opportunity to debrief the participants in the pilot scenarios prior to the recruitment of study participants. Debrief will be led using the standardised ACLS algorithms and non-technical skills measured by the outcome assessment tools.

Performance measures

The Ottawa Global Rating Scale (GRS) is a tool that has shown validity and reliability evidence for measuring non-technical CRM skills.23 It assesses each of the following categories on a seven-point anchored scale: situational awareness, leadership, problem solving, communication, resource utilisation and overall performance.

A simple checklist that has been shown to be a reliable tool for PEA arrest published by the Heart and Stroke Foundation will be used to assess for adherence to ACLS algorithm (technical skills) in addition to the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.24 Within each category, the participant gets a dichotomous option (‘yes’ or ‘no’) for each item required, and the final score will be determined by tallying up the ‘yes’ scores.

Outcome measures

We will assess the relationship of biological and chronological age with:

CRM skills (primary outcome), as measured by the total Ottawa GRS23 score and the Heart and Stroke ACLS checklist for PEA.24

Learning from high-fidelity simulation education (secondary outcome), measured by change in performance from pretest, immediate post-test and retention post-test using the Ottawa GRS scale23 and the ACLS checklist for PEA.24

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics will be calculated for all variables of interest. Continuous measures such as age will be summarised using means and SD, whereas categorical measures will be summarised using counts and percentages.

To test the first hypothesis, the association between CRM skills and age measured using the Ottawa GRS and ACLS checklist, we will use a Pearson correlation (or Spearman correlation for non-normal data). We will then conduct a multivariable linear regression model analysis including demographic variables of interest (ie, past simulation experience and previous ACLS management) and time of retention test (ie, between 3 months and 6 months following initial post-test) as predictor variables. This model will also adjust for the correlation among observations taken from the same site.

The secondary outcome of change in the Ottawa GRS and ACLS checklist score over time will be analysed using a repeated measures analysis of variance, adjusting for the correlation among observations from the same participant. This analysis will be followed by specific pairwise comparisons: (1) pretest (scenario 1) compared with immediate post-test (scenario 2) and (2) immediate post-test (scenario 2) compared with retention post-test (scenario 3).

Sample size estimate

Our primary analysis looks at the relationship between age and CRM skills. A sample of 60 will provide 80% power at alpha of 0.05 to detect a correlation of 0.72 or greater (a high correlation) compared with a null hypothesis value of 0.5 (a moderate correlation). The sample size calculation was carried out using PASS V.12 (Hintze, J. (2014). NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, Utah).

Patient involvement

Patients were not involved in the development of the research question and outcome measures. Study participants are physicians, therefore patients were not approached for participation.

Impact, limitations and dissemination

This study will explore the relationship between ageing with CRM performance and learning in a simulated clinical setting. As such, the results will be a critical first step in informing continuing professional development practices and be the foundation for future studies investigating this medical population. Furthermore, no matter the outcome, the results of this study will be part of the discussion in helping shape national policy regarding practice assessment and help guide continuing professional development for ageing physicians.

This study aims to investigate whether ageing is correlated with baseline CRM skills in ACPs and determine whether ageing influences the acquisition and retention of CRM skills from theatre-based simulation and debriefing. If ageing does have an impact on CRM skills in physicians, then methods can be implemented, aimed at assessing and intervening through continuing professional development earlier in a physician’s career. Hopefully, this can prevent potential negative patient outcomes. One such method could be through the use of simulation, but this study will first delineate whether this method of instruction needs to be modified for older more experienced clinicians. If they do not learn the same way as residents, and we are delivering instruction based on research conducted with junior learners, then this may be ineffective for older physicians. This study will help clarify this uncertainty.

The main challenge of this study is recruiting and scheduling physicians. Financial compensation has been identified as a barrier for staff participation in simulation sessions.25 To mitigate this, we include continuing professional development section 3 credits for all participants in order to facilitate recruitment, allowing participants to track and document their skills, knowledge and experience that is gained formally and informally as it is mandatory for all practising physicians to complete a required number of credits to maintain their status with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. There also is potential for an unintentional recruitment bias since ageing physicians likely did not train with mannequin-based simulation. To account for this, investigators will present at grand rounds with each acute care department to emphasise the implications of this study. Another challenge might be the concept of biological age versus chronological age. This study will be using both chronological and biological age to mitigate this potential confounder.

Findings will be presented at local and national meetings (eg, Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society Annual Meeting), and we plan to publish our study in a peer-reviewed journal as an open access article. Lastly, we intend to discuss findings at national specialty societies, interested provincial colleges of medicine and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, with the goal of developing and implementing appropriate continuing education strategies for ACPs.

In conclusion, the results from this study will fill in the gap in the literature on whether physicians’ age influences baseline CRM performance and also learning from simulation. The results will be a critical first step in helping shape and develop continuing education tailored to physicians’ age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank and acknowledge: current members of the Perioperative Anesthesia Clinical Trials Group (Eric Jacobsohn, (chair) University of Manitoba; Scott Beattie, University of Toronto; André Denault, Université de Montréal; Ron George, Dalhousie University; Hilary Grocott, University of Manitoba; Richard Hall, Dalhousie University; Heather McDonald, University of Manitoba; Daniel I. McIsaac, University of Ottawa; C. David Mazer, University of Toronto; Manoj Lalu, University of Ottawa; Sonia Sampson, Memorial University; Alexis Turgeon, Université Laval; Homer Yang, University of Ottawa); Dr Alex Kiss from Sunnybrook Research Institute for his insights on data analysis; Susan DeSousa for her assistance at the Sunnybrook Simulation Centre; and Kathrina Flores and Jessica Pacquing for their role as confederates at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Footnotes

Contributors: FA and SB contributed to secure research funding and conceived and designed all aspects of the study protocol. AB, VRL, JT, DP, CF, NK-G, YG, AK, PC, SA and SL contributed to the study design. FA, SB and SA drafted and finalised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript. This study has been endorsed by the Perioperative Anesthesia Clinical Trials Group.

Funding: At the time of submission, this study has received two grants from (1) Phil R. Manning Research Award, Continuing Medical Education, the Society for Academic Continuing Medical Education; and (2) Department of Innovation in Medical Education, Education Healthcare Grant, University of Ottawa. Dr Boet was supported by The Ottawa Hospital Anesthesia Alternate Funds Association.

Disclaimer: Funders have no role in the study design, data collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was received from the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (#20150173–01 hour) (Ottawa, Ontario) and the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Research Ethics and Human Research Protections Program (#140–2015) (Toronto, Ontario).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data sharing is not applicable for this article as no data has been analysed during this stage. Only study investigators will have access to the final trial data set to maintain privacy of participants.

References

- 1. Information CIfH: Geographic Distribution of Physicians in Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Colleges AoAM: Center for Workforce Studies: 2012 Physician Specialty Data Book, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Katz JD. Issues of concern for the aging anesthesiologist. Anesth Analg 2001;92:1487–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baird M, Daugherty L, Kumar KB. Arifkhanova A: The Anesthesiologist Workforce in 2013, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durning SJ, Artino AR, Holmboe E, et al. . Aging and cognitive performance: challenges and implications for physicians practicing in the 21st century. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2010;30:153–60. 10.1002/chp.20075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Trunkey DD, Botney R. Assessing competency: a tale of two professions. J Am Coll Surg 2001;192:385–95. 10.1016/S1072-7515(01)00770-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turnbull J, Carbotte R, Hanna E, et al. . Cognitive difficulty in physicians. Acad Med 2000;75:177–81. 10.1097/00001888-200002000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tessler MJ, Shrier I, Steele RJ. Association between Anesthesiologist Age and Litigation. Anesthesiology 2012;116:574–9. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182475ebf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eva KW. The aging physician: changes in cognitive processing and their impact on medical practice. Acad Med 2002;77:S1–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baxter AD, Boet S, Reid D, et al. . The aging anesthesiologist: a narrative review and suggested strategies. Can J Anaesth 2014;61:865–75. 10.1007/s12630-014-0194-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Norman G, Young M, Brooks L. Non-analytical models of clinical reasoning: the role of experience. Med Educ 2007;41:1140–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02914.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alam A, Khan J, Liu J, et al. . Characteristics and rates of disciplinary findings amongst anesthesiologists by professional colleges in Canada. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie 2013;60:1013–9. 10.1007/s12630-013-0006-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hedden T, Gabrieli JD. Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 2004;5:87–96. 10.1038/nrn1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duclos A, Peix JL, Colin C, et al. . Influence of experience on performance of individual surgeons in thyroid surgery: prospective cross sectional multicentre study. BMJ 2012;344:d8041 10.1136/bmj.d8041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khaliq AA, Dimassi H, Huang CY, et al. . Disciplinary action against physicians: who is likely to get disciplined? Am J Med 2005;118:773–7. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Custers EJ, Ten Cate OT. Very long-term retention of basic science knowledge in doctors after graduation. Med Educ 2011;45:422–30. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03889.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boet S, Bould MD, Fung L, et al. . Transfer of learning and patient outcome in simulated crisis resource management: a systematic review. Can J Anaesth 2014;61:571–82. 10.1007/s12630-014-0143-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, et al. . Qayyum R: Effectiveness of continuing medical education, 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khanduja PK, Bould MD, Naik VN, et al. . The role of simulation in continuing medical education for acute care physicians: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2015;43:186–93. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steadman RH. Improving on reality: can simulation facilitate practice change? Anesthesiology 2010;112:775–6. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d3e337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. . statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;2013:200–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roizen MF: RealAge: Are you as young as you can be?: Harper Collins, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim J, Neilipovitz D, Cardinal P, et al. . A pilot study using high-fidelity simulation to formally evaluate performance in the resuscitation of critically ill patients: The University of Ottawa Critical Care Medicine, High-Fidelity Simulation, and Crisis Resource Management I Study. Crit Care Med 2006;34:2167–74. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000229877.45125.CC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McEvoy MD, Smalley JC, Nietert PJ, et al. . Validation of a detailed scoring checklist for use during advanced cardiac life support certification. Simul Healthc 2012;7:222–35. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3182590b07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Savoldelli GL, Naik VN, Hamstra SJ, et al. . Barriers to use of simulation-based education. Can J Anaesth 2005;52:944–50. 10.1007/BF03022056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.