Abstract

Introduction

Delirium is a common complication in the elderly after surgery and is associated with worse outcomes. Multiple risk factors are related with postoperative delirium, such as exposure to general anaesthetics, pain and postoperative inflammatory response. Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that dexmedetomidine attenuated neurotoxicity induced by general anaesthetics, improved postoperative analgesia and inhibited inflammatory response after surgery. Several studies found that intraoperative use of dexmedetomidine can prevent postoperative delirium, but data were inconsistent. This study was designed to investigate the impact of dexmedetomidine administered during general anaesthesia in preventing delirium in the elderly after major non-cardiac surgery.

Methods and analysis

This is a randomised, double-blinded and placebo-controlled trial. 620 elderly patients (age ≥60 years) who are scheduled to undertake elective major non-cardiac surgery (with an expected duration ≥2 hours) are randomly divided into two groups. For patients in the dexmedetomidine group, a loading dose dexmedetomidine (0.6 µg/kg) will be administered 10 min before anaesthesia induction, followed by a continuous infusion at a rate of 0.5 µg/kg/hour until 1 hour before the end of surgery. For patients in the control group, normal saline will be administered with an identical rate as in the dexmedetomidine group. The primary endpoint is the incidence of delirium during the first five postoperative days. The secondary endpoints include pain intensity, cumulative opioid consumption and subjective sleep quality during the first three postoperative days, as well as the incidence of non-delirium complications and all-cause mortality within 30 days after surgery.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital (2015–987) and registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (http://www.chictr.org.cn) with identifier ChiCTR-IPR-15007654. The results of the study will be presented at academic conferences and submitted to peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

ChiCRR-IPR-15007654; Pre-results.

Keywords: elderly, major non-cardiac surgery, intraoperative dexmedetomidine, postoperative delirium

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study design will be randomised, double-blinded and placebo-controlled, with a relatively large sample size.

Anaesthesia depth (Bispectral Index) will be monitored to guide anaesthesia maintenance to ensure patients in both groups received equal depth of anaesthesia.

This is a single-centre trial, which will limit the generalisability of the results.

Only early outcomes (up to 30 days after surgery) are assessed in this trial.

The haemodynamic and anaesthetic-sparing effects of dexmedetomidine might weaken the efficiency of blindness to the treating anaesthesiologist.

Introduction

Delirium is a transient brain dysfunction that is characterised by altered consciousness, inattention, and changes in cognition or perception; it develops acutely with clinical manifestations to be fluctuated with aggressive and depressive manner during the development course.1 The prevalence of delirium varies from 12% to 51% in patients after non-cardiac surgery, and it is increased with age.2 3 The occurrence of postoperative delirium (POD) is associated with worse outcomes including prolonged mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit (ICU) stay, increased postoperative complications, high mortality rate and long-term cognitive decline.2–5

The aetiology of POD is multifactorial and includes several intraoperative factors.6 For example, exposure to general anaesthetics (eg, propofol or sevoflurane) might produce neurotoxicity,7 8 whereas reduced anaesthetic consumption by avoiding deep anaesthesia reduced the occurrence of delirium in elderly patients undergoing major non-cardiac surgery.9 Poor pain management is another risk factor of POD.6 10 It was reported that the risk of POD was 1.2 times higher for every unit increment in visual analogue pain score (an 11-point pain scale where 0 indicates no pain and 10 the most severe pain).11 Inflammation is also proposed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of POD.2 Inflammatory responses induced by surgery and anaesthesia are manifested by elevated levels of interleukins, C reactive protein and tumour necrosis factor.2 12 Studies by our group and others found that higher levels of inflammatory mediators are associated with increased risk of POD.2 13–16

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α2-receptor agonist with sedative, analgesic and anxiolytic effects.17–21 When used as a supplement during intraoperative anaesthesia, it reduces the consumption of general anaesthetics.17 Preclinical evidence suggested that use of dexmedetomidine might attenuate neurotoxicity induced by general anaesthetics.18 19 In a meta-analysis, intraoperative administration of dexmedetomidine lowers postoperative pain intensity and reduces opioid consumption.20 Clinical evidence also showed that intraoperative dexmedetomidine significantly inhibits hypersecretion of inflammatory cytokines during and after surgery.21 22

Use of dexmedetomidine during general anaesthesia may reduce POD. In paediatric patients undergoing tonsillectomy and cardiac surgery, intraoperative infusion of dexmedetomidine lowered the incidence of emergence delirium.23 24 In adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery and microvascular free flap surgery, intraoperative dexmedetomidine (comparison with normal saline) slightly decreased the incidence of delirium, although the differences were not statistically significant between the two groups possibly due to underpowered sample size.25 26 In a recent study of Deiner et al,27 use of dexmedetomidine during general anaesthesia did not reduce delirium after major non-cardiac surgery in the elderly. However, in that study, anaesthesia depth was not monitored and the consumption of anaesthetics (such as propofol and fentanyl) was similar between the two groups. It was possible that patients in the dexmedetomidine group had deeper anaesthesia, which might have increased the risk of delirium.27 Therefore, the effect of dexmedetomidine administered during general anaesthesia on the occurrence of POD needs to be evaluated further.

This study is designed to investigate whether dexmedetomidine use during general anaesthesia can decrease the incidence of POD in the elderly after major non-cardiac surgery.

Methods and analysis

Study design

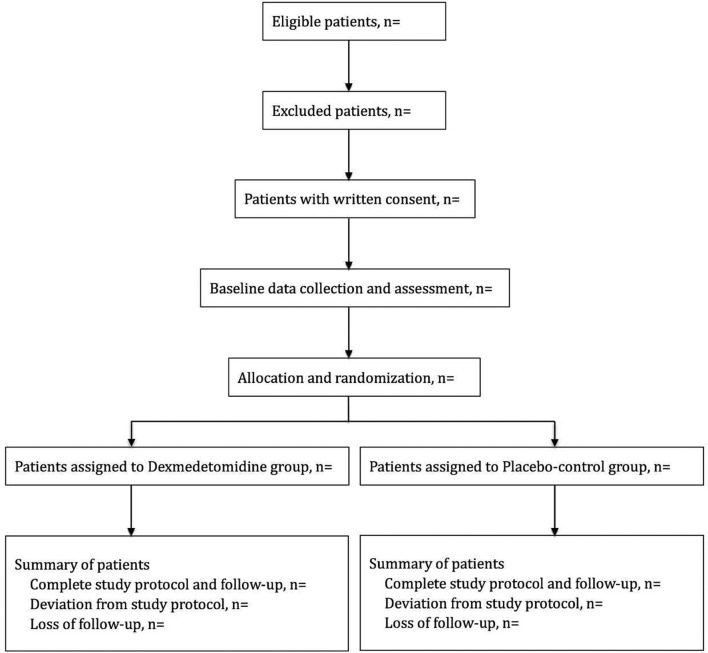

This randomised, double-blinded and placebo-controlled trial with two parallel arms was designed to test the superiority of dexmedetomidine administered during general anaesthesia on the incidence of delirium after surgery. Patients will be randomised into either the dexmedetomidine group or the control group (figure 1). The study is conducted at the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine of Peking University First Hospital.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of this study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or conduct of the study. There is no plan to disseminate the results to study participants.

Participants

Elderly patients (age ≥60 years) who are scheduled to undergo elective non-cardiac surgery with expected duration ≥2 hours under general anaesthesia are screened for inclusion. Those who meet any of the following criteria will be excluded: (1) do not provide written informed consent; (2) history of schizophrenia, epilepsy or Parkinson’s disease; (3) visual, hearing, language or other barriers which impede communication and preoperative delirium assessment; (4) neurosurgery or traumatic brain injury; (5) severe bradycardia (heart rate less than 40 beats per minute), sick sinus syndrome or atrioventricular block of degree 2 or above; (6) severe hepatic dysfunction (Child-Pugh grade C); or (7) renal failure (requirement of renal replacement therapy).

Patient recruitment and baseline data collection

Potential participants are screened by investigators the day before surgery (or on Friday for those who will undergo surgery next Monday). The study protocol, including potential risks and benefits, will be explained to patients in person. Those who do not meet the exclusion criteria are invited to participate in the study.

After obtaining written informed consent, the following baseline data are collected: demographic data, preoperative diagnosis, comorbidity, current medical therapy, previous surgery and main results of physical and laboratory examinations. Barthel Index is used to evaluate activities of daily living.28 Cognitive function is assessed with Mini-Mental State Examination.29 Preoperative delirium is assessed with the confusion assessment method (CAM).30

Randomisation, grouping and blinding

Random numbers were created by an independent statistician using SAS V.9.3 statistical package in a 1:1 ratio and were sealed in envelopes. A study coordinator, who has no knowledge of patients before randomisation and does not participate in anaesthesia and postoperative follow-up of enrolled patients, will open the envelop for random numbers and prepare the study drugs before induction of anaesthesia.

Information on randomisation, study drug preparation and group allocation will be masked from investigators who perform data collection and postoperative follow-up, anaesthesiologists, patients and other healthcare team members. Blinding will be maintained throughout the entire study period.

To ensure patients’ safety, study group allocation can be unmasked in the following conditions: occurrence of severe adverse events or any unexpected deterioration of patients’ clinical status. These situations will be documented on the case report forms (CRFs). The unmasked patients will be included in the intention-to-treat population but excluded from the per-protocol analysis.

Interventions, anaesthesia and analgesia

Intraoperative monitoring includes ECG, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oxygen saturation, end-tidal carbon dioxide, nasopharyngeal temperature, urine output and Bispectral Index (BIS). Intra-arterial pressure (including derivative dynamic parameters such as stroke volume variation by the FlowTrac system) and central venous pressure are monitored according to patients’ conditions.

Study drugs, either 200 µg (2 mL) dexmedetomidine (Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine, Jiangsu, China) or 2 mL normal saline, are diluted into 50 mL normal saline. All study drugs are colourless solutions provided in syringes of the same size and brand. The regimen of study drug administration includes a loading dose of 0.15 mL/kg (ie, 0.6 µg/kg dexmedetomidine for patients in the dexmedetomidine group) administered during a 10 min period before anaesthesia induction. This is followed by a continuous infusion at a rate of 0.125 mL/kg/hour (ie, a rate of 0.5 µg/kg/hour dexmedetomidine for patients in the dexmedetomidine group) until 1 hour before the end of surgery. Study drug infusion is performed using an infusion pump especially designed for dexmedetomidine administration (Slgo CP1000, Beijing Slgo Medical Technology).

Attending anaesthesiologists can decrease or stop study drug infusion in the following conditions: (1) severe bradycardia or hypotension which does not improve after routine treatment; (2) new-onset atrioventricular block which does not improve after routine treatment; or (3) other conditions where anaesthesiologists consider it necessary. In these conditions, the reasons that lead to any protocol deviations will be recorded on the CRFs. These patients will be included in the intention-to-treat analysis but excluded from the per-protocol analysis.

Anaesthesia is induced with intravenous sufentanil (target-controlled infusion with effect-site concentration from 0.2 to 0.5 ng/mL) and propofol (2–3 mg/kg), and maintained with intravenous sufentanil (effect-site concentration from 0.2 to 0.5 ng/mL) and propofol (4–12 mg/kg/hour), and inhalation of a 1:1 nitrous oxide–oxygen mixture. Rocuronium and/or cisatracurium are administered for muscle relaxation. Patients will be mechanically ventilated with a tidal volume of 6–8 mL/kg and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cm H2O. The mean arterial pressure is maintained above 60 mm Hg or within 20% from baseline. BIS is maintained between 40 and 60. Body temperature is maintained with air-warming and fluid heating systems. The target of nasopharyngeal temperature maintenance during surgery is from 36.0°C to 37°C.

All patients are transferred to the postanaesthesia care unit (PACU) or ICU before they are sent back to general wards. Patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) is provided for all patients, which is established with 0.5 mg/mL morphine in 100 mL normal saline and programmed to deliver a 1 mg bolus with a lockout interval of 8 min and a background infusion at 0.5 mg/hour. Supplemental morphine at a dose of 2–4 mg will be administered at 10 min intervals if the numeric rating scale (NRS) pain score (an 11-point scale where 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst pain) remains above 4 after three consecutive PCIA boluses.31 Other postoperative managements were performed according to routine practice.

Outcome assessment

Patients are followed up twice daily during the first five postoperative days and then weekly until 30 days after surgery. Investigators who are responsible for postoperative follow-up are not involved in anaesthesia and perioperative care, and are not allowed to exchange patients’ information with anaesthesiologists who take care of patients in the operating room. Before the start of the study, investigators are trained to follow the study protocol and to perform delirium assessment, and the training process is repeated at an interval of 4–6 months during the study period.2 3 31 The 4-hour training courses of delirium assessment include the following contents: (1) lectures regarding signs/symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of delirium by psychiatrists; and (2) training courses on the use of CAM and CAM-ICU on patient-actors (trained ICU physicians or nurses who act as patients with or without delirium) conducted by psychiatrists. The process continued until 100% agreement is achieved in diagnosing delirium.

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint is the incidence of delirium during the first 5 days after surgery. Delirium is assessed twice daily (at 08:00–09:00 and 19:00–20:00, respectively) with CAM for non-intubated patients30 or CAM-ICU for intubated patients.32 These delirium assessment methods had been used in our previous studies.2 3 31 For patients who are discharged or who died within 5 days after surgery, the results of the last delirium assessment will be considered the results of the missing data. These patients will be excluded when calculating daily prevalence of delirium in a post-hoc analysis.

Secondary endpoints

Postoperative pain intensities at rest and with movement are assessed with NRS pain score at 24, 48 and 72 hours after surgery, respectively.31 Cumulative morphine consumptions at these time points are recorded. Subjective sleep quality is assessed with NRS (an 11-point scale where 0 indicates the worst possible sleep and 10 the best possible sleep) at 08:00 on the first, second and third morning after surgery.3 31 Other secondary endpoints include non-delirium complications within 30 days after surgery, length of stay in hospital after surgery and all-cause 30-day mortality. Non-delirium complications are generally defined as new-onset non-delirium conditions after surgery that are harmful to patients’ recovery and require therapeutic intervention.

Safety outcomes

In the present study, adverse events are monitored from the start of study drug administration until PACU discharge or 2 hours after ICU admission. Hypotension is defined as a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg or a decrement of more than 30% from baseline. Hypertension is defined as a systolic blood pressure of more than 180 mm Hg or an increment of more than 30% from baseline. Bradycardia is defined as a heart rate of less than 40 beats per minute. Tachycardia is defined as a heart rate of more than 100 beats per minute. Desaturation is defined as SpO2 of less than 90%. Emergence agitation is defined as a Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale score of more than +2 within 30 min after extubation. Delayed extubation is defined when time to extubation is more than 2 hours (from the end of surgery) in PACU patients or more than 4 hours in ICU patients.2 22–25

Severe adverse events, that is, those that might result in patients’ disability/deformity, prolonged in-hospital stay or life-threatening events, will be reported to the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital within 24 hours. For patients who suffered harm from the present trial, medical treatment will be initiated as soon as possible and compensation will be completed according to local laws and regulations.

Data monitoring and management

Original data will be recorded on the CRFs accordingly. All data will be kept confidentially. The completed CRFs will be checked by a study coordinator who is qualified by the principal investigator. Supplementations and corrections will be made when necessary. Data entry will be performed in a double-input and double-check way with the Data Management System (Fantastic Eight Tech, Beijing, China) of the Peking University First Hospital.

The conduct of the study and the quality of data will be monitored by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital. Data management and statistical analysis will be performed by the Department of Biostatistics of Peking University First Hospital. Considering that dexmedetomidine has been widely used during general anaesthesia and its safety has been confirmed, no interim analysis will be performed and the trial will continue until the target sample size is achieved.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation

In our previous study, the incidence of delirium was 14.8% in elderly patients after non-cardiac surgery.33 Previous studies reported that intraoperative dexmedetomidine decreased the incidence of POD by 60%–77% in comparison with placebo.22 25 We assumed that the incidence of POD will be reduced from 14.8% to 7.4% (ie, a 50% reduction) in the present study. With the power set at 80% and significant level at 0.05, 564 patients are required to detect the difference. Considering a loss to follow-up rate of about 9%, we plan to enrol 620 patients in this study.

Outcome analysis

Continuous data with normal distribution will be compared using independent sample t-test. Continuous data with asymmetric distribution will be compared using independent sample Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data will be compared using χ2 test or continuity correction χ2 test. The difference (and 95% CI of the difference) between two means or medians will be estimated using the methodology of Levene’s test or Hodges-Lehmann estimator. Time-to-event data will be analysed by survival analysis, with differences between groups compared with log-rank test.

Statistical analyses will be performed with the SPSS V.14.0 and SAS V.9.3. All tests are two-tailed, and p values of less than 0.05 are considered to be statistically significant. Bonferroni adjustment is made to control type I error for multiple testing.

Discussion

This randomised, double-blinded and placebo-controlled single-centre trial was designed to investigate if dexmedetomidine administration during general anaesthesia can decrease the incidence of POD in elderly patients after major non-cardiac surgery.

In the present study, the dosing regimen of dexmedetomidine is similar to our previous study because it does not increase drug-related adverse events (such as severe bradycardia and hypotension).25 Furthermore, the CAM and CAM-ICU are used to assess delirium in patients with or without intubation, respectively.30 32 Both CAM and CAM-ICU have been validated in Chinese population.34 35 Feasibility of these two assessment tools has been confirmed in our previous studies.2 3 31 To maintain the quality of delirium assessment, investigators in charge of postoperative follow-up are trained by a psychiatrist before the study and will be retrained at an interval of 4–6 months.

Because of the haemodynamic and anaesthetic-sparing effects of dexmedetomidine, it is not very difficult for the experienced anaesthesiologists to guess which study drug is administered. This might weaken the blinding to anaesthesiologists. However, in the present study, investigators who are responsible for postoperative follow-up and delirium assessment are not involved in anaesthesia and perioperative care, and they are not allowed to exchange patients’ information with anaesthesiologists who take care of patients in the operating room. In this way, the blinding of investigators to study group assignment can be guaranteed.

The strengths of the present study include the following when compared with previous studies22–24: First, a randomised, double-blinded and placebo-controlled study design with a relatively large sample size (620 patients) is adopted. The results of the study will provide high-quality evidence. Second, the BIS level is monitored in all enrolled patients, which will help us to avoid unnecessary and potentially harmful deep anaesthesia. Third, safety data will be recorded in detail. Our study also has some limitations. One is that this is a single-centre trial, which will limit the external validity of our results. Second, only early outcomes (up to 30 days after surgery) will be explored. Third, the haemodynamic and anaesthetic-sparing effects of dexmedetomidine might weaken the efficiency of blindness to the treating anaesthesiologist.

Trial status

This study is currently at the patient enrolment and data collection stage. The current version of the study protocol is V.1.1 and was approved on 27 November 2015. Patient recruitment started on 2 December 2015 and is expected to be finished by 31 March 2018.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Xin-Yu Sun (Department of Psychiatrics, Peking University Sixth Hospital, Beijing, China) for her help in psychiatric consultation and personnel training, and Dr Xue-Ying Li (Department of Biostatistics, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China) for her help in statistical consultation. We also thank Professor Daqing Ma (Section of Anesthetics, Pain Medicine and Intensive Care, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, London, UK) for his help in revising the manuscript.

Footnotes

B-JW and C-JL contributed equally.

Contributors: D-XW and D-LM designed this study. D-LM drafted the manuscript of the protocol. D-XW critically revised the manuscript. D-LM, B-JW, C-JL, JH, H-JL, CG, Z-HW and Q-CZ participated in the conduct of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This trial was supported by Beijing Excellent Talent Support Program (no 2014000020124G025).

Disclaimer: The sponsors have no role in the study design and conduct; the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or the preparation and approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: D-XW reports lecture fees and travel expenses for lectures given at academic meetings from Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine, China, and Yichang Humanwell Pharmaceutical, China. D-LM is the primary investigator of the present study, which was supported by Beijing Excellent Talent Support Program.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol (V.1.1, issue date November 2015) was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital (2015-987). Any protocol modification will be submitted for review and approval by the ethics committee. The trial was registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (www.chictr.org.cn) with identifier ChiCTR-IPR-15007654 on 1 December 2015. Written informed consents are obtained from every patient or his/her surrogate in law.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014;383:911–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Su X, Meng ZT, Wu XH, et al. Dexmedetomidine for prevention of delirium in elderly patients after non-cardiac surgery: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2016;388:1893–902. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30580-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA 2004;291:1753–62. 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med 2012;367:30–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1112923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aldecoa C, Bettelli G, Bilotta F, et al. European Society of Anaesthesiology evidence-based and consensus-based guideline on postoperative delirium. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2017;34:192–214. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Creeley C, Dikranian K, Dissen G, et al. Propofol-induced apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes in fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Br J Anaesth 2013;110(Suppl 1):i29–i38. 10.1093/bja/aet173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xiong WX, Zhou GX, Wang B, et al. Impaired spatial learning and memory after sevoflurane-nitrous oxide anesthesia in aged rats is associated with down-regulated cAMP/CREB signaling. PLoS One 2013;8:e79408 10.1371/journal.pone.0079408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan MT, Cheng BC, Lee TM, et al. BIS-guided anesthesia decreases postoperative delirium and cognitive decline. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2013;25:33–42. 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3182712fba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vaurio LE, Sands LP, Wang Y, et al. Postoperative delirium: the importance of pain and pain management. Anesth Analg 2006;102:1267–73. 10.1213/01.ane.0000199156.59226.af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lynch EP, Lazor MA, Gellis JE, et al. The impact of postoperative pain on the development of postoperative delirium. Anesth Analg 1998;86:781–5. 10.1213/00000539-199804000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hirsch J, Vacas S, Terrando N, et al. Perioperative cerebrospinal fluid and plasma inflammatory markers after orthopedic surgery. J Neuroinflammation 2016;13:211 10.1186/s12974-016-0681-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cape E, Hall RJ, van Munster BC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of neuroinflammation in delirium: a role for interleukin-1β in delirium after hip fracture. J Psychosom Res 2014;77:219–25. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van den Boogaard M, Kox M, Quinn KL, et al. Biomarkers associated with delirium in critically ill patients and their relation with long-term subjective cognitive dysfunction; indications for different pathways governing delirium in inflamed and noninflamed patients. Crit Care 2011;15:R297 10.1186/cc10598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McGrane S, Girard TD, Thompson JL, et al. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels at admission as predictors of duration of acute brain dysfunction in critically ill patients. Crit Care 2011;15:R78 10.1186/cc10070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kazmierski J, Banys A, Latek J, et al. Raised IL-2 and TNF-α concentrations are associated with postoperative delirium in patients undergoing coronary-artery bypass graft surgery. Int Psychogeriatr 2014;26:845–55. 10.1017/S1041610213002378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shin HW, Yoo HN, Kim DH, et al. Preanesthetic dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg single infusion is a simple, easy, and economic adjuvant for general anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol 2013;65:114–20. 10.4097/kjae.2013.65.2.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li J, Xiong M, Nadavaluru PR, et al. Dexmedetomidine attenuates neurotoxicity induced by prenatal propofol exposure. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2016;28:51–64. 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sanders RD, Xu J, Shu Y, et al. Dexmedetomidine attenuates isoflurane-induced neurocognitive impairment in neonatal rats. Anesthesiology 2009;110:1077–85. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819daedd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Le Bot A, Michelet D, Hilly J, et al. Efficacy of intraoperative dexmedetomidine compared with placebo for surgery in adults: a meta-analysis of published studies. Minerva Anestesiol 2015;81:1105–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kang SH, Kim YS, Hong TH, et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine on inflammatory responses in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2013;57:480–7. 10.1111/aas.12039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li Y, Wang B, Zhang LL, et al. Dexmedetomidine combined with general anesthesia provides similar intraoperative stress response reduction when compared with a combined general and epidural anesthetic technique. Anesth Analg 2016;122:1202–10. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cao JL, Pei YP, Wei JQ, et al. Effects of intraoperative dexmedetomidine with intravenous anesthesia on postoperative emergence agitation/delirium in pediatric patients undergoing tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy: a CONSORT-prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Medicine 2016;95:e5566 10.1097/MD.0000000000005566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun Y, Liu J, Yuan X, et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine on emergence delirium in pediatric cardiac surgery. Minerva Pediatr 2017;69:165–73. 10.23736/S0026-4946.16.04227-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li X, Yang J, Nie XL, et al. Impact of dexmedetomidine on the incidence of delirium in elderly patients after cardiac surgery: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170757 10.1371/journal.pone.0170757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang X, Li Z, Gao C, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine on preventing agitation and delirium after microvascular free flap surgery: a randomized, double-blind, control study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015;73:1065–72. 10.1016/j.joms.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deiner S, Luo X, Lin HM, et al. Intraoperative infusion of dexmedetomidine for prevention of postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing major elective noncardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2017;152:e171505 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, et al. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud 1988;10:61–3. 10.3109/09638288809164103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Katzman R, Zhang MY, Wang ZY, et al. A Chinese version of the mini-mental state examination; impact of illiteracy in a Shanghai dementia survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:971–8. 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90034-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:941–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dl M, Zhang DZ, Wang DX, et al. Parecoxib supplementation to morphine analgesia decreases incidence of delirium in elderly patients after hip or knee replacement surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Anaesth Analg 2017;124:1992–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med 2001;29:1370–9. 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu P, Li YW, Wang XS, et al. High serum interleukin-6 level is associated with increased risk of delirium in elderly patients after noncardiac surgery: a prospective cohort study. Chin Med J 2013;126:3621–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leung J, Leung V, Leung CM, et al. Clinical utility and validation of two instruments (the confusion assessment method algorithm and the chinese version of nursing delirium screening scale) to detect delirium in geriatric inpatients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008;30:171–6. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang C, Wu Y, Yue P, et al. Delirium assessment using confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit in Chinese critically ill patients. J Crit Care 2013;28:223–9. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.