Abstract

Objectives

To examine the episodic disability experiences of older women living with HIV over time.

Design

Qualitative longitudinal study, conducting semistructured in-depth interviews on four occasions over a 20-month time frame. Inductive thematic analyses were conducted cross-sectionally and longitudinally.

Setting

Participants were recruited from HIV community organisations in Canada.

Participants

10 women aged 50 years or older living with HIV for more than 6 years.

Results

Two major themes related to the episodic nature of the women’s disability. Women were living with multiple and complex sources of uncertainty over time including: unpredictable health challenges, worrying about cognition, unreliable weather, fearing stigma and the effects of disclosure, maintaining housing and adequate finances, and fulfilling gendered and family roles. Women describe strategies to deal with uncertainty over time including withdrawing and limiting activities and participation and engaging in meaningful activities.

Conclusions

This longitudinal study highlighted the disabling effects of HIV over time in which unpredictable fluctuations in illness and health resulted in uncertainty and worrying about the future. Environmental factors, such as stigma and weather, may put older women living with HIV at a greater risk for social isolation. Strategies to promote dealing with uncertainty and building resilience are warranted.

Keywords: HIV, episodic disability, longitudinal analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted a longitudinal qualitative study of disability experienced by women living with HIV over the age of 50 years.

We achieved a 100% retention rate of participants who were interviewed on four occasions over a 20-month time frame.

We used a disability lens to understand the consequences of comorbid health challenges and how the environmental context influences disability over time.

This study did not include women diagnosed less than 6 years whose experiences may be very different from long-term survivors.

Introduction

Advances in HIV management have led to an increased life expectancy approaching that of the general population for people living with HIV.1 This increased longevity for those with access to antiretroviral therapy has resulted in the recognition of HIV as a chronic illness often accompanied by disability.2 Disability associated with HIV may be experienced as episodic in nature, characterised by unpredictable fluctuating periods of good and ill health.3

The Episodic Disability Framework was derived from the perspective of men and women living with HIV.3 4 The framework conceptualises disability as the health-related consequences of HIV, adverse effects of treatments and concurrent health conditions that may fluctuate over time. The framework spans physical, mental, emotional and social life domains including four dimensions of disability: symptoms and impairments, difficulties with day-to-day activities, challenges to social inclusion and uncertainty about future health that may be influenced by extrinsic (eg, social support, stigma) and intrinsic (eg, living strategies, gender and age) contextual factors.

Evidence suggests that women living with HIV have unique physical, psychosocial and biological needs.5 However, knowledge of the nature and extent of the disability experienced specifically among older women living with HIV is unclear. Understanding gender-specific disability has become more germane with the increasing number of adults over the age of 50 years and as women account for an increasingly higher proportion of adults ageing with HIV in North America.6

Existing literature suggests that disability experienced by older women living with HIV affects self-care, coping, cognition and social participation. A gender analysis of older women ageing with HIV revealed a complex model of social participation on a continuum from social isolation to social engagement.7 Older African-American women living with HIV find it more difficult to self-manage comorbid conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.8 Plach et al 9 conducted interviews with nine older women living with HIV and highlighted the importance for health providers to balance medical care with effective self-care. Psaros et al 10 identified multiple sources of uncertainty in their qualitative study examining how 19 women over 50 coped with living with HIV. Difficulty accepting the uncertainty of the disease course was a key barrier in transitioning to a healthy coping style. A recent review on ageing and neurocognitive functioning from literature involving a large cohort study in the USA found that HIV-positive women performed worse on measures of verbal learning and memory, however, mean ages were in the mid-40s.11 Hence, there is increasing importance to consider the multidimensional impact of disability experienced by women ageing with HIV.

The majority of studies on gender-related differences in older adults living with HIV were cross-sectional in design. While Plach et al 9 examined disability longitudinally, this study did not capitalise on the longitudinal design by offering insights on the disability process over time. It is important to understand how the fluctuating nature of the illness impacts on daily lives and disability experiences of older women living with HIV. As with ageing, episodic disability is a temporal process and the consequences and contributions to disablement can only be illuminated through longitudinal study. Our aim was to examine the disability experiences of older women living with HIV over time.

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal qualitative study involving a series of four semistructured interviews with older women living with HIV at 5-month intervals. Participants were recruited through HIV community organisations in Southern Ontario, through pamphlets on site and recruitment notices on websites. Eligible participants were women aged 50 years or older, who were diagnosed with HIV more than 6 years ago. Due to the large amount of data generated through longitudinal interviews, our aim was to retain a sample of 10 women overtime (yield of - 40 interviews).

We used the Episodic Disability Framework to guide the semistructured interviews. During the first interview (time 1), we asked participants to provide a general description of their health challenges including physical, cognitive, mental and emotional symptoms and impairments, difficulties carrying out day-to-day activities and challenges to social inclusion. The challenges were then explored in detail, probing for how the episodic nature, uncertainty and contextual factors affected the challenge. We explored participants’ living strategies and social supports used to address their health challenges. To promote reflection on the episodic nature of HIV, in subsequent interviews we explored the health challenges identified in time 1 and asked participants to consider what changes occurred, how these occurred and how these changes affected their functioning, disability and health. Our design allowed for emergent themes to be discussed over time. Thus, while specific challenges identified in previous interviews were explored in subsequent interviews, interviews enabled participants to identify new challenges that arose over time. Interviews were conducted by an investigator with experience in conducting qualitative interviews with vulnerable populations (NG). Participants were provided with an honorarium at the completion of each interview.

Analysis: All investigators contributed to the analyses. Investigators had complementary areas of expertise in gerontology, HIV, disability and personal experience growing older with HIV. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and entered into NVivo V.912 for data management. Longitudinal analysis requires summary and comparison of data both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Our analysis involved four steps: (1) After the time 1 interviews, two investigators (PS and NG) independently carried out line by line coding of three transcripts and developed a code book to guide our analysis.13 The remaining time 1 transcripts were then independently coded by two investigators from the research team using the code book. Using the coded transcripts at time 1, we developed in depth cross-sectional summary profiles for each participant. (2) To examine the episodic nature of each participant’s disability over time, we coded the data in a more structured way using the Episodic Disability Framework as a guide. Each investigator reviewed the time 2 transcript of a participant and documented any changes (ie, no change, improved or worsened) and/or new symptoms that emerged since time 1 in areas consistent with categories in the framework. We repeated this same process with the time 3 and time 4 transcripts for each participant. (3) We developed an in-depth summary of each participant’s experiences over time. The end result of this step of the analysis was an in-depth longitudinal summary profile that described the episodic nature of disability experienced by each participant over time. The summary profiles for each participant were independently derived by two investigators and then amalgamated. (4) We compared the longitudinal summary profiles of participants to identify thematic similarities and differences in the episodic nature of disability experiences among the participants over time.

All participants provided informed consent.

Patient and public involvement

A community member was included on the research team as one of the investigators. He reviewed and provided input on the research question and design prior to grant submission and was involved in the analysis and interpretation of the findings. Results of this study will be distributed to participants who indicated that they would like a copy of the research findings and provided contact information.

Results

Ten women ranging from 51 to 61 years of age (median: 54 years; IQR 52.2–58.7) participated in this study, all of whom completed four interviews over a 20-month period. Median time since diagnosis was 12.5 years (IQR 8–13.7). Three women reported being single, three were married or living with a partner and four were divorced. Five women received disability income support, three were working and two were seeking employment. Two women identified as visible minorities (Asian, African-Canadian) and one woman was indigenous Canadian.

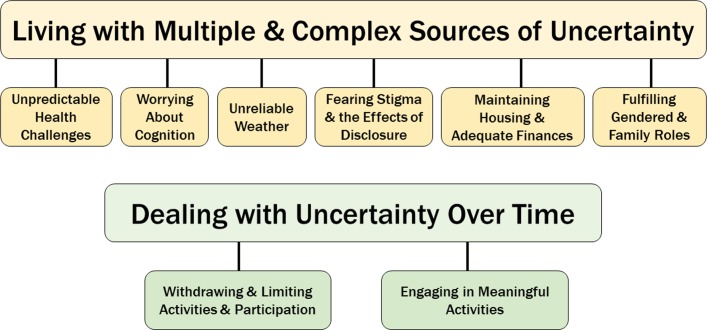

We identified two major themes related to the episodic nature of participants’ disability: (1) Living with multiple and complex sources of uncertainty over time and (2) Strategies for dealing with episodic disability over time. Themes and subthemes are summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Themes and subthemes of disability experiences of older women living with HIV over time.

Living with multiple and complex sources of uncertainty over time

Women were living with multiple, concurrent, evolving and overlapping sources of uncertainty which fluctuated over time. Some sources of uncertainty fluctuated minimally or remained stable over the period of the study. Women were managing complex and diverse fluctuations in their health challenges, comorbidities and contextual factors which contributed to their uncertainty.

Unpredictable health challenges

All participants experienced fluctuations in their health challenges over the duration of the study. For many, there were significant fluctuations in fatigue, insomnia, pain, mood and cognition. These fluctuations led to worries about whether they would have the capacity to fulfil their roles and responsibilities. For some, the uncertainty was incapacitating and meant they could not plan for activities. Some described fluctuations on a day to day basis, making it difficult to predict how much they could accomplish that day. This woman talked about the challenges of discerning a ‘good’ day from a ‘bad’ day: “…I can’t tell a good day from a bad day when I wake up. It’s just when I get someplace and it just becomes bad.” (P9).

Other fluctuations occurred over weeks or even months. Unpredictability of these health fluctuations were highlighted over time. Often a new diagnosis or health challenge would arise at one of the interviews and be resolved by the next interview. For example, one woman faced a serious illness related to a urinary tract infection during interviews 2 and 3 which had resolved by interview 4.

The myriad health challenges experienced by the women led to worries about their healthcare and whether clinicians had the knowledge to deal with HIV-related issues. Some worried specifically about the knowledge related to women’s needs.

There’s a lot of work to kind of being on top of [gynaecological symptoms], and part of that is actually…educating and convincing doctors to pursue some of the tests that I think might be necessary. (P2)

The ups and downs of the women’s health challenges led to fears of getting seriously ill to the extent that they chose to remain home rather than interact with others. These fears were more evident during the winter months when there were increased probabilities of exposure to upper respiratory tract infections and influenza.

Always when there are bugs going around, I literally hibernate in my home if I can. I carry Lysol in my car…seriously, I’ll wear a mask shopping and stuff because…I am so paranoid. (P5)

Worrying about cognition

Although many of the women were aware of normal age-related changes related to cognition and memory, lapses in memory or concentration led to concerns about HIV-related dementia in six women. Two women sought testing for cognitive impairments over the course of the study due to their worries; the results indicated normal cognitive ageing. Two were diagnosed with HIV-related dementia and both lost their drivers’ licence, though one woman successfully appealed this during the course of the study. Some women accepted their cognitive decline and developed strategies such as note writing.

Take your meds. Yeah, I have forgotten…I still forget what I’m going to do. I know a lot of people who…your attention…I got to go get something or whatever and by the time you get there I stand there and try and figure out what am I here for? (P9)

Unreliable weather

The unpredictability of adverse winter weather was a concern for seven of the women. Cold weather increased their pain, particularly joint and arthritic pain. Winter affected their mood and contributed to decreased energy and depression. Affordable activities, such as walking and cycling, were curtailed by bad weather. Many felt ‘stressed’ to be indoors and often felt an increased sense of isolation. One woman described herself as ‘hibernating’ in the winter. Some did not venture outdoors due to a fear of falling. Women were aware of the effects of winter on their mood and levels of participation and dreaded its arrival. Some worried about curtailing their outdoor and social activities and becoming isolated, “There’s not very much to do in the winter. I don’t really go out much, so I just hate it.” (P 8).

Fearing stigma and the effects of disclosure

These women worried about stigma related to gender, age, race, HIV status and sexual orientation. Unemployment or precarious employment was often attributed to ‘being older’, heterosexual or a woman, with perceptions that gay men or women of colour would get preference for coveted paid positions in HIV community organisations. Self-stigma related to HIV was evident among all women including those who appeared to thrive and those working in HIV community organisations.

I applied for a job here for my boss and I didn’t get the job and somebody else has been in that job. Somebody else who is like a lot less qualified both educationally and experientially but, you know, he’s a gay man. (P2)

Six women chose to limit their circle of disclosure due to a pervasive fear of stigma. Uncertainty related to whether people would associate with them if they revealed their HIV-positive status. Some worried about accidental disclosure. One woman described how she felt she had to limit her associations with friends from a HIV community organisation as she did not know how she would explain these relationships to her family. Many women had not disclosed to immediate family members. These worries and concerns often increased social isolation or prohibited women from seeking supports from loved ones and friends.

I’m very scared. I pick who I want to mix with because if I mix with people and they know my status, they won’t want to mix with me. Believe me, that is the truth. People do not mix with people with HIV. (P1)

Maintaining housing and adequate finances

Nine women expressed financial and housing concerns. Maintaining housing and adequate finances were closely linked as housing was often the most significant living expense. The majority of women were in precarious employment, underemployed or on government disability pensions. Women worried about ageism affecting their employment status. Many women lived in supportive housing units, which over time became undesirable due to conflicts with neighbours and concerns about living conditions. Some women had not worked in many years and had given up on finding employment. Others worked in voluntary positions with HIV community organisations.

So, I have anxieties…related to…the future…you know…financial concerns about not earning enough money, and so therefore, not having as much savings as I should, etc. etc. (P2).

Fulfilling gendered and family roles

Over time, six women expressed uncertainty related to fulfilling gendered roles primarily related to caregiving and household responsibilities. As the women were older, their children were adults. Nonetheless, women valued their role as mother. One woman discussed how her children were living at home for the summer and how she was now cooking and doing their laundry. Another woman had to accommodate her daughter and two small grandchildren in her apartment after a failed relationship. Some women who were not permanently employed took on childcare responsibilities for extended family. Several women discussed the need to care for their ageing parents.

I was having problems with being a grandmother and not being the grandma that I wanted to be, you know, doing a good job and the responsibility of being a grandmother, you know? (P9)

Dealing with uncertainty over time

The strategies that women used to navigate through the varied sources of uncertainty were revealed over time. While some women were overwhelmed and withdrew from activities and participation, others moved forward. Several women described a situation of isolation at the initial interviews but were able to make changes so that by the end of the study they described a life which was more engaged.

Withdrawing and limiting activities and participation

Five women’s sense of being overwhelmed led them to withdraw from activities, becoming more socially isolated. This was particularly evident in women who were uncertain of the consequences of HIV disclosure. Rather than seeking support and sharing their challenges with others, they chose to limit whom they disclosed to and avoid others. One woman’s social withdrawal was related to fears of getting ill. Some recognised the need for social support but were reluctant to ‘burden’ family and friends. Other women were restricted by the winter weather further reinforcing their isolation.

One of the reasons I was late this morning, my sister called me, I was almost going through the door and I couldn’t tell her no because I didn’t want to lie to her like, where are you going? Why can’t you talk to me? And I sit and I had to talk to her for about 15 min. She wouldn’t let go. I told her I got to go, I was telling her about something on sale today so she had the impression that I’m going to go get this thing that’s on sale and didn’t know I’m coming all the way here but I couldn’t let her know. (P4)

Engaging in meaningful activities

Five women sought activities that they felt contributed to their lives in meaningful ways. For a few this meant paid employment, though as noted this was often precarious in nature. The HIV community organisations provided an outlet for volunteer activities for many women; this had the added benefits of not having to worry about disclosure and providing access to support groups and education. Educating themselves about HIV,

led women to describe gaining a sense of control over their lives. The significant fluctuations in participation highlighted the relevance of the longitudinal inquiry; for example, one woman’s life seemed hopeless at interviews 1 and 2; she was depressed, isolated and said she could not plan for the future. By interview 4, it appeared that she had turned her life around; she changed her way of interacting with her children and ex-husband, got a pet to provide some structure and meaning in her life and found a part-time job. As she stated, “I’ve learnt I have resilience”. (P3)

The women who appeared to thrive over time tended to maintain a positive outlook, some through social comparisons with others. They developed a sense of purpose whether through caring for pets, family members or work activities. Many made lifestyle changes, including watching their diet, being more physically active and quitting smoking. In contrast, some women felt unable to plan or look at the future and described living ‘day by day’. A few, in spite of the uncertainties, were forward thinking and had goals and aspirations.

I keep believing in my head I’m going to get a little bit better. I mean, maybe I won’t get a whole lot better; I’m never obviously going to get back to what I was, you know, five years ago or whatever. (P10)

Discussion

This study highlights the needs of older women living with HIV related to the episodic nature of disability and the associated uncertainty. The longitudinal study design allowed for a more nuanced understanding of uncertainty. In some instances, the source of uncertainty was relatively stable over time (eg, finances and housing) leading to chronic stressors. The episodic nature of chronic illness is increasingly recognised as an important characteristic impacting on disability.14 Our study provided insights into the disabling effects of HIV in which unexpected fluctuations in illness and health resulted in uncertainty and worrying about the future. Uncertainty is a defining feature of older people living with HIV15 and is a contributor to mental distress.16 This study reinforces a model of disability of people ageing with HIV which had uncertainty as the core affecting all components of disability including symptoms and impairments, difficulties in day-to-day activities and challenges to social participation.17 18 By following the women over time, the complexities of managing multiple health challenges which fluctuated differentially, is highlighted.

Strengths of this research include the prolonged engagement and retention of all participants over 20 months. In many instances, the participants were dealing with multiple fluctuating health and social issues which often affected their ability to participate and engage in their lives. If a single interview had occurred on a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ day, the portrayal would be much different and the challenges of the episodic nature of the illness would not be evident. Other strengths are use of a disability lens as a foundation for this research which focused attention on the health consequences of the comorbidities, how physical and mental health diagnoses affect peoples’ lives and how environmental and personal contextual factors interact with these over time. The longitudinal design of the study highlighted the uncertainty associated with the challenges of managing multiple symptoms, comorbidities and complex lives. Given the potential consequences and the centrality of uncertainty in these women’s lives, developing strategies to deal with stress and uncertainty in the overall management of people living with HIV is essential.

Limitations include our recruitment process through HIV community organisations, as participants who access these resources may represent a more engaged and mobile group with less disability. We also did not include women who were recently diagnosed with HIV, whose experiences may be very different to women who are longer-term survivors and living with the long-term consequences of chronic HIV inflammation, long-term toxicity of older medications and having left the work force in the past prior to the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy. We also recognise that some sources of uncertainty may be similarly experienced by men and younger women living with HIV. Additionally the 20-month time frame of the study may have been insufficient to see fluctuations in more stable sources of uncertainty such as housing and unemployment.

The women in our study experienced high levels of stress similarly reported by others.11 Stress-related factors may accelerate cognitive ageing in people living with HIV.11 Though many questions remain about the causal relationship, there is an association between anxiety and mild cognitive impairment in the general older population.19 A multimodal integrative approach to the management of worry and anxiety, which includes exercise, mindfulness and cognitive training recommended for the general population,19 is likely to be appropriate for a HIV population.

Current models of disability highlight the importance of the environmental context. Our longitudinal study followed the seasons over time and highlight how the uncertainty of weather impacted mobility and social participation of the participants. Weather is a risk factor for social isolation, health and well-being in the general older adult population,20 but yet to be specifically considered in the context of HIV. Given that older people living with HIV are at increased risks for the deleterious effects of social isolation,21 strategies to combat this are warranted.

Following participants over time revealed multiple forms of stigma experienced by women living with HIV and how it added to the complexity of uncertainty. Other gendered societal variables such as oppression and economic dependence may also contribute to maintaining stigmatising attitudes.5 Uncertainty related to the possible reactions from those who were disclosed to prevented some women from receiving necessary supports. Many of these concerns were not unfounded as women had experienced unwanted disclosure from health providers and alienation from their families. Older women’s reluctance to disclose their status, even to family members, is of particular concern given their increased vulnerability for social isolation.7 22 The perception that some people living with HIV receive preferential treatment due to varying characteristics (eg, gender, ethnicity, age) speaks to the need for women to navigate self-stigma within the HIV community in addition to within their personal lives. HIV community organisations should consider the inclusiveness of programmes to address stigma and provide opportunities for the diversity of people ageing with HIV.

The diversity of the challenges experienced by these women highlights the importance of an interprofessional approach to HIV management. As HIV continues to evolve into a chronic illness, there is a need to include rehabilitation professionals who focus on client-centred management of disability on the care team. Rehabilitation strategies promote self-management approaches which help to deal with uncertainty through building skills and promoting self-efficacy.23 For example, occupational therapists can support women’s personal, environmental and occupational needs through facilitating workplace participation, advocating for funding and assisting in navigating healthcare and political systems.24 We agree that self-management programmes need to be flexible and tailored to the individual needs of people living with HIV.23 25 We also support the caution of Bernardin et al 23 that not all needs can be met through chronic disease self-management programmes. Basic social determinants of health such as food and housing security may need to be met through concurrent programming.

Future research should include a quantitative examination of the synergistic and additive effects to further delineate the relationship between the episodic nature of disability and uncertainty in older women and men living with HIV. Additionally, in Canada indigenous populations are disproportionately affected by HIV and further exploration of their specific disability challenges are warranted. Ultimately, the effectiveness of strategies to mitigate stress and uncertainty and minimise disability in older women living with HIV needs to be determined.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: PS, KKO, SN and LL developed the research question and designed the study. NG collected the data. PS, KKO, SN, LL, LB and NG participated in the data analysis. PS drafted the manuscript. KKO, SN, LL, LB and NG contributed to the critical revision and redrafting of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) under grant HHP 131556. KKO and SN are supported by CIHR New Investigator Awards.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This research was approved by Research Ethics Boards of McMaster University and University of Toronto.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e349–e356. 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30066-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johs NA, Wu K, Tassiopoulos K, et al. . Disability Among Middle-Aged and Older Persons With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:83–91. 10.1093/cid/cix253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Brien KK, Bayoumi AM, Strike C, et al. . Exploring disability from the perspective of adults living with HIV/AIDS: development of a conceptual framework. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:76 10.1186/1477-7525-6-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O’Brien KK, Davis AM, Strike C, et al. . Putting episodic disability into context: a qualitative study exploring factors that influence disability experienced by adults living with HIV/AIDS. J Int AIDS Soc 2009;12:30 10.1186/1758-2652-12-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durvasula R. HIV/AIDS in older women: unique challenges, unmet needs. Behav Med 2014;40:85–98. 10.1080/08964289.2014.893983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stoff DM, Colosi D, Rubtsova A, et al. . HIV and Aging Research in Women: An Overview. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2016;13:383–91. 10.1007/s11904-016-0338-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siemon JS, Blenkhorn L, Wilkins S, et al. . A grounded theory of social participation among older women living with HIV. Can J Occup Ther 2013;80:241–50. 10.1177/0008417413501153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Warren-Jeanpiere L, Dillaway H, Hamilton P, et al. . Taking it one day at a time: African American women aging with HIV and co-morbidities. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014;28:372–80. 10.1089/apc.2014.0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Plach SK, Stevens PE, Keigher S. Self-care of women growing older with HIV and/or AIDS. West J Nurs Res 2005;27:534–53. 10.1177/0193945905275973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Psaros C, Barinas J, Robbins GK, et al. . Reflections on living with HIV over time: exploring the perspective of HIV-infected women over 50. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:121–8. 10.1080/13607863.2014.917608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vance DE, Rubin LH, Valcour V, et al. . Aging and neurocognitive functioning in hiv-infected women: a review of the literature involving the women’s interagency HIV study. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2016;13:399–411. 10.1007/s11904-016-0340-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. NVivo qualitative data analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 2010;9. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thomson R, Holland J. Hindsight, foresight and insight: The challenges of longitudinal qualitative research. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2003;6:233–44. 10.1080/1364557032000091833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vajravelu S, O’Brien K, Moll S, et al. . The impact of the episodic nature of chronic illness: a comparison of Fibromyalgia, Multiple Sclerosis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Edorium J Disabil Rehabil 2016;2:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosenfeld D, Ridge D, Lob GV, et al. . Vital scientific puzzle or lived uncertainty? Professional and lived approaches to the uncertainties of ageing with HIV. Health Sociology Review 2014;23:20–32. 10.5172/hesr.2014.23.1.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Furlotte C, Schwartz K. Mental Health Experiences of Older Adults Living with HIV: Uncertainty, Stigma, and Approaches to Resilience. Can J Aging 2017;36:125–40. 10.1017/S0714980817000022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Solomon P, O’Brien K, Wilkins S, et al. . Aging with HIV: a model of disability. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2014;13:519–25. 10.1177/2325957414547431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Solomon P, O’Brien K, Wilkins S, et al. . Aging with HIV and disability: the role of uncertainty. AIDS Care 2014;26:240–5. 10.1080/09540121.2013.811209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lenze EJ, Butters MA. Consequences of anxiety in aging and cognitive decline. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;24:843–5. 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clarke PJ, Yan T, Keusch F, et al. . The Impact of Weather on Mobility and Participation in Older U.S. Adults. Am J Public Health 2015;105:1489–94. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Emlet CA. An examination of the social networks and social isolation in older and younger adults living with HIV/AIDS. Health Soc Work 2006;31:299–308. 10.1093/hsw/31.4.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grodensky CA, Golin CE, Jones C, et al. . "I should know better": the roles of relationships, spirituality, disclosure, stigma, and shame for older women living with HIV seeking support in the South. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2015;26:12–23. 10.1016/j.jana.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bernardin KN, Toews DN, Restall GJ, et al. . Self-management interventions for people living with human immunodeficiency virus: a scoping review. Can J Occup Ther 2013;80:314–27. 10.1177/0008417413512792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Akhtar NF, Garcha RK, Solomon P. Experiences of women aging with the human immunodeficiency virus: a qualitative study: Expériences vécues par des femmes vieillissant avec le virus de l’immunodéficience humaine : étude qualitative. Can J Occup Ther 2017;84:253–61. 10.1177/0008417417722574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Swendeman D, Ingram BL, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Common elements in self-management of HIV and other chronic illnesses: an integrative framework. AIDS Care 2009;21:1321–34. 10.1080/09540120902803158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.