Abstract

Background: Among people with spinal cord injury (SCI), minorities experience a disproportionately higher burden of diseases. Knowledge of data quality by race/ethnicity will help better design racial health disparity research and understand potential errors/biases. Objective: To investigate racial/ethnic differences in response completeness in a longitudinal SCI database. Methods: This study included 7,507 participants (5,483 non-Hispanic whites, 1,414 non-Hispanic blacks, and 610 Hispanics) enrolled in the National SCI Database who returned for follow-up between 2001 and 2006 and were aged ≥18 years at follow-up. Missing data were defined as any missing, unknown, or refusal response to interview items. Results: The overall missing rate was 29.7%, 9.5%, 9.7%, 10.7%, 12.0%, and 9.8% for the Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique-Short Form (CHART) economic self-sufficiency subscale, CAGE questionnaire, drug use, Diener's Satisfaction with Life Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire, and pain severity, respectively. The missing rate for the CHART measure was significantly higher among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics than among non-Hispanic whites, after controlling for demographics, injury factors, mode of data collection, and study sites. The missing data in the other outcome measures examined were also significantly higher among non-Hispanic blacks than among non-Hispanic whites but were not significantly different between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Conclusion: Our study highlights the importance of research methodology designed to improve non-response or response incompleteness, particularly in non-Hispanic blacks, as we move to reduce racial/ethnic disparities and strive to explain how and why disparities occur in the SCI population.

Keywords: data quality, minority health, spinal cord injuries, surveys and questionnaires

Minorities experience a disproportionately higher incidence, prevalence, mortality, and burden of diseases, and addressing these health disparities has become a national priority in the United States.1 When examining outcomes of persons with spinal cord injury (SCI), the significance of racial/ethnic (hereafter termed “racial”) health disparities is particularly critical. The percentage of racial minorities in the SCI population has increased over the past five decades. Moreover, the incidence of SCI is disproportionately higher among blacks than among whites.2 Compared with whites, blacks and Hispanics living with SCI tend to have worse physical and psychosocial outcomes.3–9 Further investigation is required to examine the nature of such disparities, explore mechanisms by which these disparities occur, and develop interventions to improve the health of the minority SCI population.

A longitudinal study can be beneficial in health disparity research. Of relevance to the SCI community, a longitudinal study allows the investigation of long-term secondary conditions after SCI by various sociodemographic backgrounds. Mail and telephone survey methodology is particularly appealing in this population, not only for examining subjective well-being of participants, but also for reasons of cost, convenience, and transportation concerns. However, loss to follow-up, non-response, and response incompleteness could skew the results and limit the generalizability to the population of interest.10–14 Without more research on racial differences in missing data and measurement quality, the current national commitment to reduce health disparities can be compromised.

In the present study, we documented the extent of incompleteness in response to questions of sensitive topics and examined the role of race/ethnicity on data quality among individuals enrolled in a longitudinal SCI database. Multiple factors (personal characteristics, mode of data collection, and study sites) were also taken into account while assessing the racial differences in missing data. This information will inform the design of methods to promote the attainment of high-quality and reliable data from people, regardless of racial background. It will also provide insight into the potential bias in SCI health disparity research that results from racial variation in data quality.

Methods

Study participants

The National Spinal Cord Injury Database (NSCID) captures data from about 6% of new SCI cases in the United States.15 Since its inception in the early 1970s, 29 federally funded SCI Model Systems (SCIMS) centers have contributed data to the database. Data have been collected on demographics, injury characteristics, medical complications, functional status, and psychosocial outcomes of eligible subjects at initial hospital care (Form I) and annual evaluations (Form II). Form II follow-up is currently completed at post-injury years 1 and 5 and every 5 years thereafter, until one of the following occurs: death, neurologic recovery, or withdrawal of consent. The inclusion and exclusion criteria, data collection process, quality control, and collaborating centers of the database have been described in detail elsewhere.15 The Institutional Review Board at each SCIMS center approved data collection and utilization.

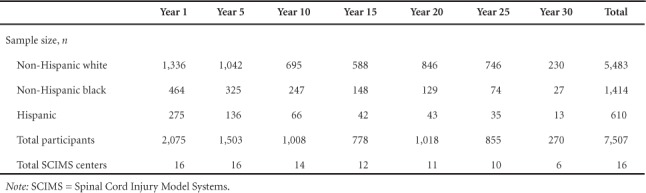

The present study included 7,507 NSCID participants from 16 SCIMS centers, who completed the Form II follow-up between March 2001 and September 2006 when various psychosocial outcomes were included in the database. Additional inclusion criteria were (1) age ≥18 years at follow-up, (2) discernible degree of neurological deficit, and (3) classification as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic all races. Non-Hispanic other races (Native American, Asian/Pacific Islander, some other races, and those categorized as multiracial) were not included because they represent only 3% of NSCID participants, which prevents reliable statistics. For those with more than one follow-up during the study period, status at the latest contact was included in the analyses. The final sample size for each post-injury year and racial group is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample size by post-injury year

Measures

Data on race/ethnicity were obtained during initial hospital care by asking NSCID participants the following questions, using US Census Bureau guidelines for coding: (1) Do you have a Latino or Hispanic background? (2) What race are you? If participants answered yes to the first question, they were assigned to the Hispanic group, regardless of race. Among those without Hispanic background, we distinguished non-Hispanic white and black participants based on their response to the second question.

We examined the missing data rates of the following self-reported measures included in the NSCID: Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique-Short Form (CHART),16 CAGE questionnaire,17 drug use, Diener's Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS),18 Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ),19 and pain severity. Missing data were defined as any missing, unknown, or refusal response to the interview items.

CHART was used to measure social participation by six subscales in the database: physical independence, cognitive independence, mobility, occupation, social integration, and economic self-sufficiency. The missing rate for each subscale was 7.9%, 8.4%, 8.5%, 9.3%, 10.8%, and 29.7%, respectively. We selected the economic self-sufficiency subscale, which had the highest missing rate among all subscales, for further analysis. The economic self-sufficiency subscale asks the following multiple-choice questions: (1) Approximately what was the combined annual income, in the last year, of all family members in your household? (2) Approximately how much did you pay last year for medical care expenses?

The CAGE questionnaire was used to identify an alcohol problem by asking the following yes/no questions: (1) Have you ever felt you should Cut down on your drinking? (2) Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? (3) Have you ever felt bad or Guilty about your drinking? (4) Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover (Eye-opener)? The missing rate for the total CAGE score was 9.5%. Participants were also asked to identify their use of illegal drugs or prescribed medications for non-medical reasons during the past year. The missing rate for drug use was 9.7%.

Subjective overall life satisfaction was assessed with Diener's SWLS, which consists of five statements: (1) in most ways my life is close to my ideal, (2) the conditions of my life are excellent, (3) I am satisfied with my life, (4) so far I have gotten the important things I want in life, and (5) if I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. Each is rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Because the missing rate was similar across the five items (10.1%, 10.1%, 10.0%, 10.1%, and 10.3%, respectively), the present analysis was limited to the total SWLS score (missing rate, 10.7%).

The 10-item PHQ was used to identify major depressive syndrome and also to indicate the severity of depression, which had missing rates of 10.8% and 12.0%, respectively. We limited the analyses to the measure of severity of depression, which had a higher missing rate. The usual level of pain over the past 4 weeks was also rated by participants, using a 0 to 10 scale. The overall missing rate for pain severity was 9.8%.

Sociodemographic variables, including education, marital status, employment, and primary payer, were updated at each follow-up. Gender and neurologic deficits were assessed during initial hospital care. The mode of data collection was also documented: (1) interview by phone, (2) interview in person, (3) self-administered by mail or in the clinic, and (4) combination of the above methods.

Statistical analysis

The missing rate was calculated for each outcome variable at each post-injury year, stratified by race/ethnicity. The significance of racial differences in missing rates was examined using the chi-square test. Multiple logistic regression was conducted to assess the effect of race/ethnicity on missing data for each outcome variable after accounting for potential confounding factors, including the mode of data collection, age at injury, gender, marital status, education, employment, primary payer, years since injury, and severity of injury. To minimize bias from regional differences in data collection practices, we divided the SCIMS centers into four groups, based on their loss to follow-up rates at post-injury years 1 and 5, and included it as a control variable in multiple logistic regression. The loss to follow-up rates defining these four groups were: (I) year 1, <15%, and year 5, < 30%; (II) year 1, 15%–24%, and year 5, 30%–39%; (III) year 1, 25%–34%, and year 5, 40%–44%; and (IV) year 1, ≥35%, and year 5, ≥45%. Subgroup analyses were also conducted within individual SCIMS centers to examine the effect of regional variation. Because the results of subgroup analyses did not meaningfully change the conclusion about racial differences in data quality, only aggregate data are presented. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.0 (SAS Institute).

Results

Compared with non-Hispanic white (hereafter termed “white”) participants, non-Hispanic black (hereafter termed “black”) and Hispanic participants were more likely to be younger, single, less educated, and unemployed (Table 2). The black and Hispanic groups had a higher percentage of Medicaid recipients and a lower percentage of private insurance beneficiaries than did the white group. Although the overall majority of Form II data collection was conducted by phone interviews, face-to-face interviews were more common among blacks and Hispanics than among whites. SCIMS centers with higher loss to follow-up rates seemed to have a higher percentage of Hispanic and black participants than of white participants.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and injury characteristics by race/ethnicity

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and injury characteristics by race/ethnicity (CONT.)

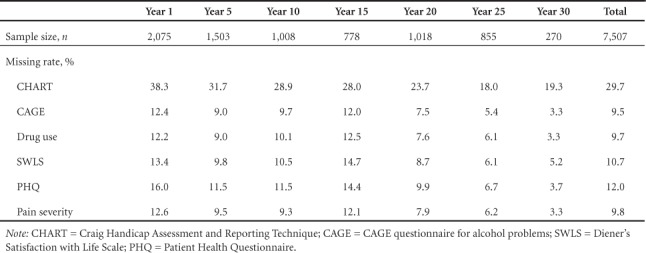

As shown in Table 3, CHART economic self-sufficiency questions had the highest missing rate among outcome measures across post-injury years. Missing data seemed to be more problematic during the early years of injury than during the later years (≥20 years). Racial differences in missing data were noted for all outcome measures across different post-injury years, although the significance level varied (Figure 1). The missing rate for CHART economic self-sufficiency was highest among blacks, followed by Hispanics and finally whites, from post-injury year 1 to year 20 (p < .05). A similar trend in missing data (blacks > Hispanics > whites) was observed for all other measures, particularly at post-injury year 5 (p < .05). Although it was not statistically significant, Hispanics seemed to have the highest missing rate among the racial groups for all outcome measures at post-injury year 30.

Table 3.

Missing data rate by post-injury year

Figure 1.

Missing data rates for self-reported outcome measures in the National Spinal Cord Injury Database by race/ethnicity and post-injury year. Missing data rates were determined for outcome measures captured by Form II survey, including (A) economic self-sufficiency, assessed by the Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique (CHART), (B) alcohol problems, assessed with the CAGE questionnaire, (C) drug use, (D) satisfaction with life, assessed by Diener's Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), (E) depression, assessed by Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), and (F) pain severity. NHW = non-Hispanic white; NHB = non-Hispanic black. *p < .05.

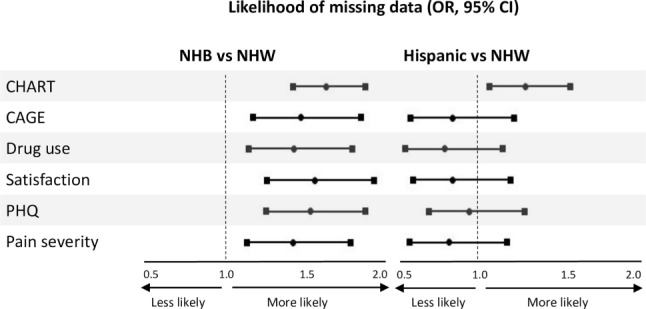

After adjusting for potential confounding factors, the odds of missing data in responses to CHART economic self-sufficiency questions were about 67% higher among blacks than among whites (odds ratio [OR], 1.67; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45–1.92). The odds of missing data for all other outcome measures were similarly and significantly higher among blacks than among whites (Figure 2). Individuals of Hispanic origin were about 30% more likely than whites were to have missing data in responses to CHART economic self-sufficiency questions (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.07–1.58), after controlling for confounding factors. The missing rates of other outcome measures did not differ significantly between the white and Hispanic groups (p > .05).

Figure 2.

Racial differences in the likelihood of missing data for self-reported outcome measures in the National Spinal Cord Injury Database. Adjusted odds ratios (OR; circles) and 95% confidence intervals (CI, squares) of missing data in outcome measures captured for non-Hispanic black (NHB) participants (left) and Hispanic participants (right) versus non-Hispanic white (NHW) participants. CHART = Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique; CAGE = CAGE questionnaire for alcohol problems; SWLS = Diener's Satisfaction with Life Scale; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire.

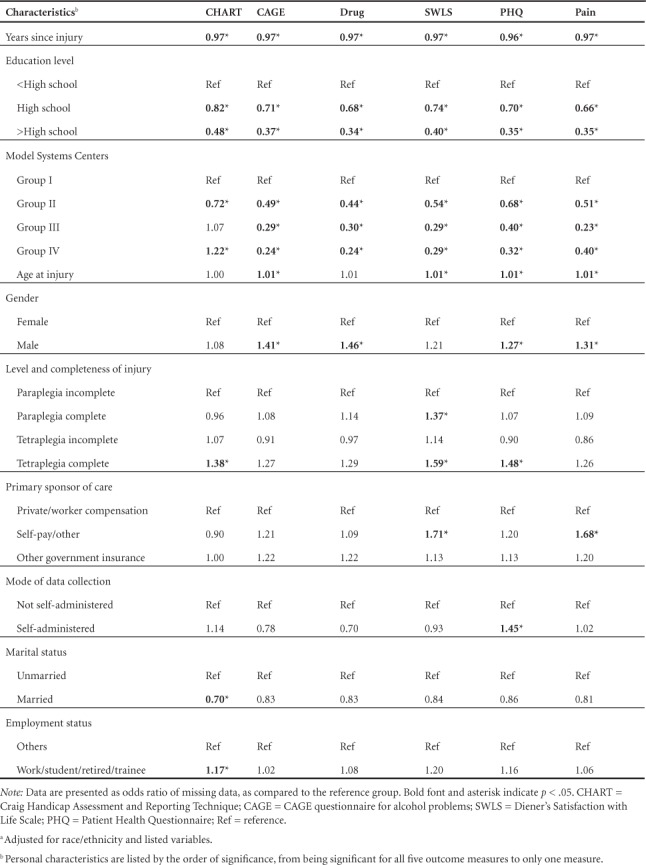

Other factors that were significantly associated with missing data for each outcome variable are summarized in Table 4. Later post-injury years and a higher education level were associated with a lower missing data rate across all outcome variables. The SCIMS centers that had a higher loss to follow-up rate tended to have a lower missing data rate among respondents for all outcome measures except the CHART economic self-sufficiency scale. For most of the outcome variables, a higher missing rate was more common in males and in people having SCI at older age and more severe injury. Compared with other modes of data collection, the self-administered data collection method associated with a higher missing data rate for the depression variable (p = .004), but a lower missing rate for the drug use variable (p = .056).

Table 4.

Personal characteristics associated with missing data: Results from multiple logistic regression a

Discussion

The current study examined the significance of racial differences in missing data for various self-reported outcomes among 7,507 individuals with SCI who were registered in a longitudinal SCI database and returned for follow-up assessments between 2001 and 2006. The finding of a higher missing data rate among minorities than among whites is generally consistent with previous studies of recruitment, retention, non-response, or response incompleteness in the general population.14,20–23

Many of the interview questions were personal and private, such as those about household income, alcohol and drug use, and personal feelings. Differential issues of trust by race/ethnicity might make one group less likely than others to respond to these questions. This trust issue, however, could not be appropriately addressed by the present study because of the constraints of the existing database. Racial matching between data collectors and participants may also contribute to whether or how participants respond. Previous studies in the general population have shown that the cultural match between interviewers and participants would more easily elicit feelings of trust.14,24 Johnson et al also suggested that mistrust in the medical system, lack of racial concordance between physicians and patients, and culturally inappropriate communication would decrease health care participation among minorities.25 Considering that the majority of the SCIMS data collectors are white females, it may be culturally uncomfortable for individuals of racial minorities to answer sensitive questions, particularly during face-to-face interview, which could consequently contribute to refusal. This raises the importance of increasing the diversity and intercultural competency of data collectors to improve their engagement with NSCID participants of different cultures. This finding also supports the necessity of regular monitoring of data quality and providing feedback to data collectors.

Several of these measures have not been validated in diverse groups of the SCI population and may not have cultural relevance to different racial groups, thereby resulting in non-response or incomplete data.19,26–28 For example, Dhalla and Kopec reviewed studies of the CAGE questionnaire for alcohol misuse assessment and concluded that it was an appropriate instrument in medical and surgical inpatients, ambulatory medical patients, and psychiatric inpatients, but did not perform well in primary care patients, white women, prenatal women, and college students.26

This study identified higher missing data rates during the early years of injury. Since post-injury year 1 or even year 5 (if participants missed their first anniversary follow-up) is the first time that study participants are exposed to Form II interview questions, general cooperation may play a key role in determining response completeness or missing data. Individuals who return for follow-up at later years are likely to be more cooperative and willing to answer questions, which contributes to a lower missing data rate regardless of race/ethnicity.

Previous studies suggested that people who have a higher education level might be able to comprehend the survey questions better and as a result are more likely to respond.12,13,23 This is supported by the current study of people with SCI, in which we observed an inverse relationship between education level and missing data rate across all outcome measures. The present finding that SCIMS centers with a higher loss to follow-up rate tended to have lower missing data rates among respondents seems to echo previous studies in the general population that suggested a trade-off between an increased response rate and a decreased response completeness.12,23,29 Other center-level factors, such as administrative supports and data collection practices, that are attributable to data quality deserve further research. These control factors seem to well explain the differences in missing data between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites regarding CAGE, drug use, SWLS, PHQ, and pain measures (Figure 2). In contrast, the missing data rate for these five measures remained higher among blacks than among whites after controlling for demographics, injury factors, mode of data collection, and participating SCIMS centers. For CHART economic self-sufficiency questions about household income and medical expenses, a high missing rate (29.7%) is not surprising, given the required knowledge of the facts and sensitivity nature of the questions. However, the differential missing rate by race/ethnicity, higher in both Hispanics and blacks than in whites even after accounting for other factors under investigation, is interesting and deserves further research.

Limitations

The study findings need to be interpreted with caution given the following limitations. The effect of language barrier on missing data and associated bias could not be addressed, given the small number of individuals who were not English or Spanish speakers in the NSCID. Similarly, because of a limited sample size, the other races were excluded from this study. Race/ethnicity reflects many complex and interrelated factors, including socioeconomic status, health behaviors and beliefs, acculturation, racism, and environment.30 The present study addressed some, but not all, of these factors. Finally, readers should note the general constraints of the NSCID that have been described in previous publications, such as hospital-based sampling, loss to follow-up, and other generalizability issues.15

Conclusion

This is the first study conducted to examine, systematically, racial differences in response incompleteness or missing data in a longitudinal study of people with SCI. As we think about making conclusions regarding racial health disparities, it is important to determine first if there are any significant differences between participants with regard to data quality and how that might affect our conclusions. This study provides the foundation for future investigations that aim to identify best practices and develop training manuals and guidelines on longitudinal data collection among individuals of culturally diverse groups. For example, with the knowledge of a higher missing data rate among blacks, we might ask for an additional review of the interview form for any missing information and further attempt to resolve incomplete data before the close of an interview. The mechanism for handling refusals during data collection, particularly while interviewing minorities, may deserve further discussion and standardization across study sites, as well. In addition, cultural adaptations or racial/ethnic matching of data collectors and prospective participants may encourage participation and improve missing data rates. As we move to reduce racial/ethnic disparities and strive to explain how and why disparities occur in the SCI population, it is critical to improve non-response or response incompleteness, particularly in the minority group. Future studies are also needed to assess whether or how this non-response bias impacts SCI health disparity research.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by funding from the National Institutes on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR 90DP0083). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this article do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services. . HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2011. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=10. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- 2. Chen Y, He Y, DeVivo MJ.. Changing demographics and injury profile of new traumatic spinal cord injuries in the United States, 1972–2014. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016; 97( 10): 1610– 1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fyffe DC, Deutsch A, Botticello AL, Kirshblum S, Ottenbacher KJ.. Racial and ethnic disparities in functioning at discharge and follow-up among patients with motor complete spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014; 95( 11): 2140– 2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gary KW, Nicholls E, Shamburger A, Stevens LF, Arango-Lasprilla JC.. Do racial and ethnic minority patients fare worse after SCI?: A critical review of the literature. NeuroRehabilitation. 2011; 29( 3): 275– 293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kennedy P, Kilvert A, Hasson L.. Ethnicity and rehabilitation outcomes: The Needs Assessment Checklist. Spinal Cord. 2015; 53( 5): 334– 339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krause JS, Saladin LK, Adkins RH.. Disparities in subjective well-being, participation, and health after spinal cord injury: A 6-year longitudinal study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2009; 24( 1): 47– 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lad SP, Umeano OA, Karikari IO, . et al Racial disparities in outcomes after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013; 30( 6): 492– 497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mahmoudi E, Meade MA, Forchheimer MB, Fyffe DC, Krause JS, Tate D.. Longitudinal analysis of hospitalization after spinal cord injury: Variation based on race and ethnicity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014; 95( 11): 2158– 2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meade MA, Lewis A, Jackson MN, Hess DW.. Race, employment, and spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004; 85( 11): 1782– 1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gorey KM, Trevisan M.. Secular trends in the United States black/white hypertension prevalence ratio: Potential impact of diminishing response rates. Am J Epidemiol. 1998; 147( 2): 95– 99; discussion 100–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greenland S. Response and follow-up bias in cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1977; 106( 3): 184– 187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Helasoja V, Prattala R, Dregval L, Pudule I, Kasmel A.. Late response and item nonresponse in the Finbalt Health Monitor survey. Eur J Public Health. 2002; 12( 2): 117– 123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Korkeila K, Suominen S, Ahvenainen J, . et al Non-response and related factors in a nation-wide health survey. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001; 17( 11): 991– 999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK.. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006; 27: 1– 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen Y, DeVivo MJ, Richards JS, SanAgustin TB.. Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems: Review of program and national database from 1970 to 2015. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016; 97( 10): 1797– 1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whiteneck GG, Charlifue SW, Gerhart KA, Overholser JD, Richardson GN.. Quantifying handicap: A new measure of long-term rehabilitation outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992; 73( 6): 519– 526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984; 252( 14): 1905– 1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S.. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985; 49( 1): 71– 75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB.. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999; 282( 18): 1737– 1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cunningham WE, Hays RD, Burton TM, Kington RS.. Health status measurement performance and health status differences by age, ethnicity, and gender: Assessment in the medical outcomes study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2000; 11( 1): 58– 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fongwa MN, Cunningham W, Weech-Maldonado R, Gutierrez PR, Hays RD.. Comparison of data quality for reports and ratings of ambulatory care by African American and White Medicare managed care enrollees. J Aging Health. 2006; 18( 5): 707– 721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nelson KM, Geiger AM, Mangione CM.. Racial and ethnic variation in response to mailed and telephone surveys among women in a managed care population. Ethn Dis. 2004; 14( 4): 580– 583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Steffen AD, Kolonel LN, Nomura AM, Nagamine FS, Monroe KR, Wilkens LR.. The effect of multiple mailings on recruitment: The Multiethnic Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008; 17( 2): 447– 454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dotinga A, van den Eijnden RJ, Bosveld W, Garretsen HF.. The effect of data collection mode and ethnicity of interviewer on response rates and self-reported alcohol use among Turks and Moroccans in the Netherlands: An experimental study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005; 40( 3): 242– 248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA.. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Publ Health. 2004; 94( 12): 2084– 2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dhalla S, Kopec JA.. The CAGE questionnaire for alcohol misuse: A review of reliability and validity studies. Clin Invest Med. 2007; 30( 1): 33– 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hall K, Dijkers M, Whiteneck G, Brooks CA, Krause JS.. The Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique (CHART): Metric properties and scoring. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 1998; 4: 16– 30. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pavot W, Diener E.. Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychol Assess. 1993; 5: 164– 172. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stang A, Jockel KH.. Studies with low response proportions may be less biased than studies with high response proportions. Am J Epidemiol. 2004; 159( 2): 204– 210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stewart AL, Napoles-Springer AM.. Advancing health disparities research: Can we afford to ignore measurement issues? Med Care. 2003; 41( 11): 1207– 1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]