Abstract

Background: Trust influences healthcare through the willingness to seek care, disclose sensitive information, adhere to treatment, and satisfaction with care. Understanding factors that influence trust may help in physician–patient relationship particularly at end of life.

Objectives: We explored the association between trust and other demographic and psychosocial factors. We also explored the performance of the single-item Degree of Trust scale (0 best to 10 worst) compared with the validated five-item Trust in Medical Profession scale (5 best to 25 worst).

Design: A secondary analysis of prospectively collected data was performed. Trust scores completed by 100 patients were correlated with age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, anxiety, depression, and hopefulness (Herth Hope Index [12 best to 48 worst]).

Setting/Subjects: The study was conducted on 100 patients in an outpatient Supportive Care Center in a cancer center in Houston, Texas.

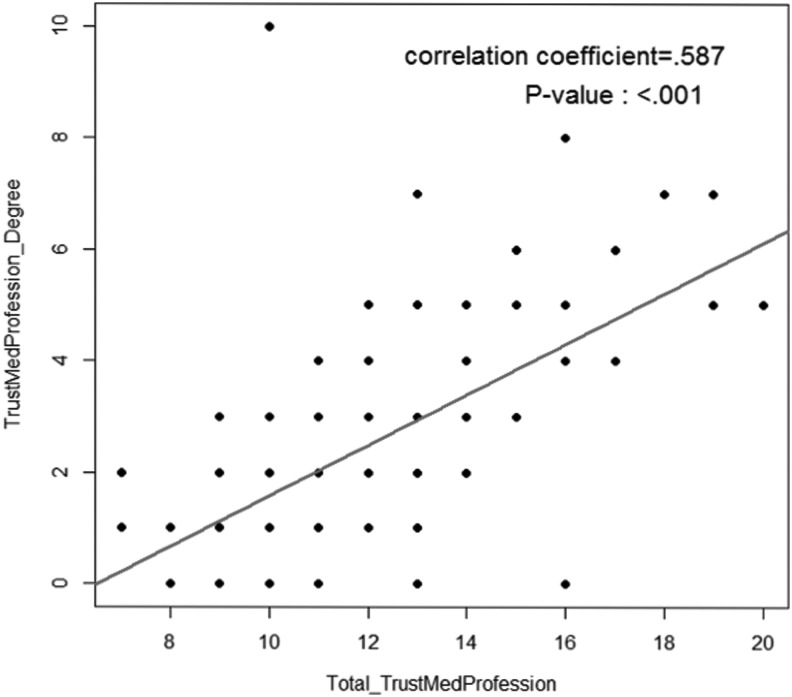

Results: Median age was 57 years (49–65), depression was 6 (3–9), and hopefulness was 22 (20–25). Trust in Medical Profession score was 13, 11–14 (median, IQR) and Degree of Trust score was 2, 1–4 (median, IQR) with moderate correlation (r = 0.587, p < 0.001). On evaluating performance of Degree of Trust scale to the validated Trust in Medical Profession scale, a moderately high performance was found (Youden's J = 0.73; Topleft = 0.21). Older age (p = 0.02) lower depression scores (p < 0.01) and more hopefulness (p = 0.01) were associated with higher levels of trust.

Conclusions: Trust was associated with older age, less depressed, and more hopeful patients. A single 0–10 item trust scale was found to perform adequately compared with a multiple-item questionnaire.

Introduction

Trust is generally defined as a state of accepted vulnerability to the actions of another party with the expectation that the action provided is important to the trustor.1–4 In the medical profession, trust is important for patients to willingly seek, reveal sensitive information, and accept care, which, in turn, gives intrinsic value into patient–physician relationships.2,5 Unfortunately, with continuous changes in the healthcare system, shortened medical visits, and conflicting responsibilities between third-party payers and patient care, the development of general trust in the medical profession is at risk.2,6–10 This, in turn, may affect the quality of trust of a patient to their physician.11 Lower levels of trust have been shown to result in lower rates of seeking care and preventative services.1 In contrast, physicians perceived that patients with lower trust levels tend to be more demanding.12 As a clarification, trust should also be distinguished from a generalized trust into the medical profession against individual healthcare providers.

Dimensions of medical trust include fidelity, competence, honesty, confidentiality, compassion, reliability, and communication.13,14 These dimensions may be interrelated and affect each other. Among these, Hillen et al. in an interview of cancer patients found that competence was frequently ranked the most important.14 However, competency perceived by a patient can differ from the definition of healthcare professionals in that it also refers to displaying a caring and compassionate behavior, devotion of time and attention, and communicating clearly and completely.1,11,14 More importantly, when trust is built, it is not easily affected by medical shortcomings like poor communication or unsatisfactory results.14

In a recent prospective study of patient perception of physician compassion, the single-item Degree of Trust scale in the medical profession instrument was found to be significantly associated with the higher perception of compassion (r = 0.23; p = 0.02).15 As part of the clinical trial, this is a secondary analysis we conducted to determine predictors of trust in the medical profession among advanced cancer patients, including patient's age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, anxiety, depression, and hopefulness. This may provide further knowledge of the influence of these factors on trust in the medical profession and, in turn, on patient–physician relationship, particularly in those with more serious medical conditions and end of life. We also explored the performance of the single-item Degree of Trust scale used in the previous study compared with the validated five-item Trust in Medical Profession scale. We wanted to explore this further as high-performing single-item instruments may be a powerful tool to use in busy clinical settings to determine important clinical and psychosocial factors that may affect care.

Methods

In this preliminary study, we conducted a secondary analysis of data collected in the course of a prospective randomized controlled trial of physician compassion to a more optimistic versus a less optimistic message.15 One hundred patients' data were analyzed for trust scores and correlated with data of the patient's age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, anxiety, depression, and hopefulness. Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (cutoff ≥8),16 whereas hopefulness was measured using the Herth Hope Index17 (total hopefulness, 12 best hope to 48 worst hope) and a 10-point Degree of Hopefulness scale (0 best hope to 10 worst hope). Trust in Medical Profession18 was scored on a 5–25 scale with an inverse scoring applied (5 best trust to 25 worst trust) for this analysis to match the inversely scored Degree of Trust scale (0 best trust to 10 worst trust). As a result, lower values indicated more trust. Degree of Trust was scored using a reverse 10-point scale with lower values showing more trust.

Correlation between each of continuous covariates and outcome of interest was assessed using Spearman correlation analysis. Association between each of categorical covariates and outcome of interest was examined by Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis test. Fisher's exact test was used to assess the relationship between each of categorical covariates and categorized outcome of interest. Univariate/multivariate general linear model was applied to assess important covariates, including patients' demographic and clinical characteristics on patients' medical trust score.

Results

One hundred patients completed the assessments of trust and were included in this study. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The two trust instruments used were the five-item Trust in the Medical Profession questionnaire (scored 5–25) and the Degree of Trust scale (scored 0–10). Trust scores showed a median of 13, 11–14 (median, IQR) for Trust in Medical Profession and 2, 1–4 (median, IQR) for Degree of Trust with moderate correlation (r = 0.587, p = <0.001, Fig. 1). In the Degree of Trust scale, 70% of patients scored trust at ≤3. On evaluating performance of Degree of Trust scale to the validated Trust in Medical Profession scale, a Youden's J score of 0.73 and Topleft score of 0.21 were found (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Variables (N = 100)

| Variables | N |

|---|---|

| Median age (Q1–Q3) | 57 (49–65) |

| Female gender | 52 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 78 |

| African American | 8 |

| Hispanic | 7 |

| Others | 7 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 58 |

| Not married | 42 |

| Education level | |

| ≥Completed college | 42 |

| <College | 55 |

| Unknown | 3 |

| Religion | |

| Christian/Protestant/Catholic | 80 |

| Other | 20 |

| Primary cancer diagnosis | |

| Breast | 16 |

| Gastrointestinal (colon, liver, pancreas) | 19 |

| Genitourinary | 7 |

| Gynecological | 10 |

| Head and neck | 15 |

| Lung | 18 |

| Other | 15 |

| Cancer stage | |

| Locally advanced | 20 |

| Metastatic | 74 |

| Recurrent | 6 |

| Previous cancer treatment | |

| 1–2 types of chemotherapy | 42 |

| >2 types of chemotherapy | 47 |

| Targeted therapy/phase 1 | 19 |

| Radiation | 61 |

| Surgery | 57 |

| Other | 6 |

| Median HADS anxiety (median, Q1–Q3) | 7 (4–9) |

| Median HADS depression (median, Q1–Q3) | 6 (3–9) |

| Median trust in medical profession (median, Q1–Q3) | 13 (11–14) |

| Median degree of trust (median, Q1–Q3) | 2 (1–4) |

| Median total hopefulness (Herth Hope Index) (median, Q1–Q3) | 22 (20–25) |

| Median degree of hopefulness (median, Q1–Q3) | 2 (0–5) |

HADS–Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale.

FIG. 1.

Scatter plot of trust in medical profession and degree and trust in medical profession (N = 99).

Table 2.

Comparison of Trust in Medical Profession versus Degree of Trust Scale (N = 99)

| Trust (TMP ≤15) | Distrust (TMP >15) | Sensitivity 0.923 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trust (Deg ≤3) | 69 | 1 | Specificity 0.802 |

| Distrust (Deg >3) | 17 | 12 | Youden's J 0.725 |

| Total | 13 | 86 | Topleft 0.212 |

TMP, trust in medical profession.

For Trust in Medical Profession, the univariate analysis showed a significant association with age (median, IQR = 57, 49–65; p = 0.02), depression (median, IQR = 6, 3–9; p = 0.05), total hopefulness (Herth Hope Index; median, IQR = 22, 20–25; p = 0.03), and degree of hopefulness (median, IQR = 2, 0–5; p = 0.02). These factors showed a low-moderate correlation (r = 0.20–0.24). In the multivariate analysis, only age (p = 0.055) and total hopefulness (p < 0.01) had a significant association with trust. However, the total variance for the multivariate analysis was 0.11, suggesting only 11% of these explained the variation in trust. Anxiety, gender, ethnicity, and education level were not significantly associated with Trust in Medical Profession scores. Summary of results is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Association between Trust And Other Clinical Variables

| Trust in medical profession | Degree of trust | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ra | p | N | ra | p | |

| Univariate regression analysis | ||||||

| Age | 100 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 99 | 0.28 | <0.01 |

| HADS anxiety | 100 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 99 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| HADS depression | 100 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 99 | 0.27 | <0.01 |

| Total hopefulness (Herth Hope Index) | 100 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 99 | 0.17 | 0.09 |

| Degree of hopefulness scale (0–10) | 100 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 99 | 0.40 | <0.01 |

| Gender | 0.52b | 0.77b | ||||

| Male | 48 | 48 | ||||

| Female | 52 | 51 | ||||

| Ethnicity | 0.12b | 0.24b | ||||

| White | 78 | 77 | ||||

| African American | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Hispanic | 7 | 7 | ||||

| Other | 7 | 7 | ||||

| Education level | 0.35b | 0.88b | ||||

| ≥College | 42 | 42 | ||||

| <College | 55 | 55 | ||||

| Others | 3 | 2 | ||||

| Multicovariate regression analysis | ||||||

| p | p | |||||

| Age | 0.055 | 0.02 | ||||

| Total hopefulness (Herth Hope Index) | 0.01 | <0.01 | ||||

Spearman's rank order correlation coefficient.

Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test/Kruskal–Wallis test.

For Degree of Trust, the univariate analysis showed a significant association with age (median, IQR = 57, 49–65; p < 0.01), depression (median, IQR = 6, 3–9; p < 0.01), and degree of hopefulness (median, IQR = 2, 0–5; p < 0.01). These factors likewise showed a low-moderate correlation (r = 0.27–0.40). In the multivariate analysis, only age (p = 0.02) and depression (p < 0.01) were significantly associated with trust. However, the total variance for the multivariate analysis was 0.15, suggesting that only 15% of these explained the variation in degree of trust. Anxiety, total hopefulness, gender, ethnicity, and education level were not significantly associated with Degree of Trust scores. Summary of results are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

Our results showed that older age, lower depression scores, and more hopefulness were associated with higher levels of trust. A better understanding of a level of hope of a patient might help a clinician's plan of care for a patient. As the disease progresses, it is not surprising that patients will become less hopeful of achieving cure or long-term survival. Our data suggest that changes in hope might be associated with decreased trust in the clinical teams. Interventions aimed at realistic hope in patients and caregivers are potentially capable of having impact on the level of trust. A person with lower levels of hope may need increased communication with interdisciplinary services, including chaplaincy, social work, and counselors. These may then help with increased adherence to plans of care. Hope and trust in caregivers may also likely influence hope and trust in patients, and this variable needs further research to determine clinical implications.

However, there was a low predictive value of these factors to trust in the medical profession. This may be explained by the complexity of trust and that there may be multiple other factors that influence trust. We did not observe an association between gender, ethnicity, and education level to trust. This result was similar to that found by Thom et al.12 in a study on 732 patients in an office setting and to that found by Hall et al.2 in a telephone survey of 502 adults. Because of its design, this study is not able to focus on causality. With the overall association between the different variables to trust being low, we hypothesize that there are other predictors that were not captured in this study, and more research is necessary to better characterize the association between trust and these other patient variables. Furthermore, more research to compare levels of trust in the medical profession between different medical fields and in patients in varying stages of disease may also be beneficial. In the meantime, our findings suggest that lower trust should be suspected with younger age, higher levels of depression, and lower levels of hopefulness.

Our results also showed a moderately high correlation between scores of Trust in Medical Profession questionnaire and Degree of Trust scale. The Degree of Trust scale also demonstrated a moderately high performance as compared with the validated Trust in Medical Profession questionnaire. A single 0–10 dimension of trust appears to be a reasonable tool to use instead. Moreover, multiple-item questionnaires may be difficult to complete in a busy clinic setting and when patients also have multiple medical visits. More research is needed to confirm and validate a single-item questionnaire as a way of determining trust in clinical practice. If these researches confirm the excellent performance of this tool, it may become much easier to assess and follow up the level of trust of patients in subsequent encounters. Degree of trust may also need to be monitored over time. Initially high levels of trust may decrease if treatment toxicities or failures occur. However, levels of trust may increase if treatments lead to improved patient's conditions.

In conclusion, trust in the medical profession may be associated with older, less depressed, and more hopeful patients. Further research is needed to better characterize the association between trust, these factors as well as other factors not captured in this study. Moreover, a single 0–10 item trust scale was found to perform adequately compared with a multiple-item questionnaire. Continued research is needed in developing clinically applicable instruments to evaluate patient's levels of trust that can also record changes in trust over time. These can then be used to target factors and develop interventions to increase trust in the medical profession, particularly that it might be possible that trust decreases secondary to poor outcomes of cancer treatments or that it may increase in those with good outcomes.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Thom DH, Hall MA, Pawlson G: Measuring patients' trust in physicians when assessing quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:124–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall MA, Camacho F, Dugan E, Balkrishnan R: Trust in the medical profession: Conceptual and measurement issues. Health Serv Res 2002;37:1419–1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baier A: Trust and antitrust. Ethics 1986;96:231–260 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD: An integrative model of organization trust. Acad Manage Rev 1995;20:709–733 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall M, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra A: Trust in physicians and medical institutions: What is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q 2001;79:613–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little M, Fearnside M: On trust. Online J Ethics 1997:1–16 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mechanic D: Changing medical organization and the erosion of trust. Milbank Q 1996;74:171–189 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blendon R, Benson J: Americans' views on health policy: A fifty-year historical perspective. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pescosolido BA, Tuch SA, Martin JK: The profession of medicine and the public: Examining American's changing confidence in physician authority from the beginning of the ‘health care crisis’ to the era of health care reform. J Health Soc Behav 2001;42:1–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlesinger M: A loss of faith: The sources of reduced political legitimacy for the American medical profession. Milbank Q 2002;80:185–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKinstry B, Ashcroft RE, Car J, et al. : Interventions for improving patients' trust in doctors and groups of doctors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;19:CD004134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thom DH, Kravitz RL, Bell RA, et al. : Patient trust in the physician: Relationship to patient requests. Fam Pract 2002;19:476–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearson SD, Raeke LH: Patients' trust in physicians: Many theories, few measures and little data. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:509–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillen MA, Onderwater AT, van Zwieten MC, et al. : Disentangling cancer patients' trust in their oncologist: A qualitative study. Psychooncology 2012;21:392–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanco K, Rhondali W, Perez-Cruz P, et al. : Patient perception of physician compassion after a more optimistic vs a less optimisitic message: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2015;1:176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herth K: Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: Development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs 1992;17:1251–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall M: Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Serv Res 2005;5:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]