Abstract

Background: Little is known about the composition, availability, integration, communication, perceived barriers, and work load of pediatric palliative care (PPC) providers serving children and adolescents with cancer.

Objective: To summarize the structure and services of programs to better understand successes and gaps in implementing palliative care as a standard of care.

Methods: Cross-sectional online survey about the palliative care domains determined by the Psychosocial Care of Children with Cancer and Their Families Workgroup.

Subjects: A total of 142 surveys were completed with representation from 18 countries and 39 states.

Results: Three-fourths of sites reported having a PPC program available for the pediatric cancer population at their center. Over one-fourth (28%) have been in existence less than five years. Fewer than half of sites (44%) offered 24/7 access to palliative care consultations. Neither hospital-based nor local community hospice services were available for pediatric patients at 24% of responding sites. A specific inpatient PPC unit was available at 8% of sites. Criteria for automatic palliative referrals (“trigger” diagnoses) were reported by 44% respondents. The presence of such “triggers” increased the likelihood of palliative principle introduction 3.41 times (p < 0.003). Six percent of respondents perceived pediatric oncology patients and their families “always” were introduced to palliative care concepts and 17% reported children and families “always” received communication about palliative principles. The most prevalent barriers to palliative care were at the provider level.

Discussion: Children and adolescents with cancer do not yet receive concurrent palliative care as a universal standard.

Keywords: : pediatric cancer, pediatric oncology, pediatric palliative care

Introduction

Although the field of pediatric palliative care (PPC) has experienced exponential growth in the past decade,1 many children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer still do not have access to palliative care services in an integrated, inclusive way.2 PPC may be defined as both a specialty service as well as an approach to pediatric medical care, which encompasses the total care of a child and family, including pain and complex symptom management, psychosocial and spiritual support, transitions of care navigation, and interdisciplinary interventions.3 These concepts are critical for children with cancer because their diagnoses carry intense symptom burdens,4 emotional adjustments,5,6 and psychosocial impacts.7 Integration of palliative care at the time of diagnosis throughout the treatment trajectory may not only alleviate suffering, but also provide an extra layer of support across the care continuum.

After reviewing the evidence, the collaborative Standards for Psychosocial Care of Children with Cancer and Their Families Workgroup (supported by the Mattie Miracle Cancer Foundation; www.mattiemiracle.com) recently determined that palliative care should be standard for children and adolescents with cancer.8,9 Specifically, the recommendations included early introduction of palliative care concepts such as comprehensive symptom assessments integrating direct patient report, evidence-based communication techniques, and solicitation of preferences to enable shared decision making, regardless of the child's prognosis.8 Championed by families and interdisciplinary care teams, the concept of palliative care as a standard of care was then widely endorsed by ten professional pediatric oncology organizations.10

The present study was conducted to assess the current status of PPC practice to inform recommendations for future implementation of palliative care as a standard of care in pediatric oncology settings. This survey was designed to report on the structure, processes, and range of services offered by palliative care teams serving children with cancer and their families. The diversity in palliative care team staffing and workforce has been recently described elsewhere.10 This article summarizes the interdisciplinary team infrastructure, service availability, service offerings, timing of introduction, triggers to consultation (a trigger being a diagnosis or prognosis predetermined to warrant consideration of an automatic referral to the palliative care subspecialty team), communication approach, educational resources, and perceived barriers of PPC programs serving children with cancer.

Methods

Design and sample

Medical settings providing clinical care to children with cancer were asked to select one representative to complete the study survey. An announcement of the survey was posted with review and permission on three nationally focused listservs: The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine listserv (AAP SOHPM); the American Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Palliative Care Working Group listserv (ASPHO WG); the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Pediatric Palliative Care Special Interest Group listserv (AAHPM SIG). For inclusion of a global perspective, the Societe Internationale D'Oncologie Pediatrique Palliative Care Special Interest Group listserv was included as a fourth distribution approach (SIOP SIG). The SIOP Palliative SIG had reviewed and approved the palliative care standard of care document before publication, as this standard was intended to be universally applicable even in resource-limited care settings.

Measures

Survey questions were designed by a collaborative, interdisciplinary study team according to the Tailored Method of Survey Design.11 The survey instrument (available as Appendix 1) consisted of 36 questions. The survey was independently reviewed, piloted, revised, and repiloted by an interdisciplinary team (two psychosocial specialists, a nurse, two pediatric oncologists, a social worker, and PPC providers) before administration on SurveyMonkey©.

Data collection and analysis

The Office of Human Subjects Research Protections at the National Institutes of Health determined that the survey format and content qualified as exempt from full Institutional Review Board review. A link to the SurveyMonkey© questionnaire was sent in an introductory email inviting listserv participants to complete the survey with three reminder emails sent in two-week intervals.

The analyses were descriptive and univariate in nature. The study team utilized counts for categorical variable responses. For missing responses due to skip patterns in the survey, the number of responders was used as the denominator (actual n).

Cumulative logistic models were used to determine associations between (1) the presence of trigger diagnosis and time point of introduction to palliative care principles; and, (2) perceived service capacity and frequency of palliative care introduction with geographic location (regions of United States and country), number of referrals, or programmatic years in service.12 The cumulative logit model was utilized due to the ordinal nature of the response variables. The majority of associations was determined using the proportional odds model (the simplest form of cumulative logit model). These data were run in SPSS Statistics.

Results

A total of 142 surveys were completed. Characteristics of the survey respondents are provided as Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Survey Respondents

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Profession | n = 142 respondents |

| Palliative care physician | 70 (49.3) |

| Oncologist | 29 (20.4) |

| Nurse practitioner/physician's assistant | 17 (11.9) |

| Nurse | 11 (7.8) |

| Social worker | 6 (4.2) |

| Child-life specialist | 4 (2.8) |

| Psychologist | 3 (2.1) |

| Psychiatrist | 1 (0.7) |

| Chaplain | 1 (0.7) |

| Care settinga | n = 142 respondents |

| Inpatient | 123 (86.6) |

| Outpatient clinic | 94 (66.2) |

| Hospice | 43 (30.3) |

| Other | 27 (19.0) |

| Survey access | n = 141 respondents |

| The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAP SOHPM) | 75 (53.2) |

| Societe Internationale D'Oncologie Pediatrique Palliative Care Special Interest Group (SIOP PODC SIG) | 23 (16.3) |

| American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Pediatric Palliative Care Special Interest Group listserv (AAHPM SIG) | 14 (9.9) |

| Pediatric Palliative Care Network | 14 (9.9) |

| Other | 6 (4.3) |

| American Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Palliative Care Working Group (ASPHO WG) | 5 (3.6) |

| Referred from a local Palliative Care Team | 4 (2.8) |

More than one response allowed for this question.

Palliative program description

Three-fourths of sites reported having a PPC program (75%); 15% have access to a contact person deemed a PPC provider, but not to a PPC program; 7% did not have any PPC services available for patients receiving cancer-directed therapy; and 3% utilized adult palliative care providers for pediatric care needs. Respondents without palliative care access for children with cancer were from international locations (7/10) and from locations within the United States (3/10). More than a quarter of responding palliative care programs had been in existence for less than 5 years (28%) with the oldest site in existence for 20 years. Program descriptions are available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Palliative Care Programs

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Oncology cases (annual) | n = 142 (100) |

| 1–50 | 30 (21.1) |

| 51–100 | 38 (26.8) |

| 101–150 | 25 (17.6) |

| >150 | 49 (34.5) |

| Location | n = 141 (99) |

| Midwest USA | 38 (27) |

| Southern USA | 30 (21.3) |

| Western USA | 24 (17) |

| Northeastern USA | 20 (14.2) |

| Asia | 9 (6.4) |

| South America | 8 (5.7) |

| Africa | 6 (4.3) |

| Canada | 4 (2.8) |

| Europe | 2 (1.4) |

| Access to pediatric-specific palliative care providers | n = 142 (100) |

| Yes | 107 (53.4) |

| Pediatric provider but no pediatric program | 21 (14.8) |

| No | 10 (7) |

| Adult program covers pediatric needs | 4 (2.8) |

| Longevity of PPC program | n = 116 (81.7) |

| <5 years ago | 32 (27.6) |

| 6–10 years ago | 44 (37.9) |

| 11–20 years ago | 31 (26.7) |

| >20 years ago | 2 (1.7) |

| Not sure | 7 (6) |

| Palliative care team structurea | n = 120 (84.5) |

| Physician | 112 (93.3) |

| Nurse practitioner | 88 (73.3) |

| Social worker | 82 (68.3) |

| Registered nurse | 74 (61.7) |

| Chaplain | 67 (55.8) |

| Child-life specialist | 49 (40.8) |

| Administrative assistant | 41 (34.2) |

| Psychologist | 40 (33.3) |

| Case manager | 24 (20) |

| Art therapist | 23 (19.2) |

| Pharmacist | 23 (19.2) |

| Massage therapist | 14 (11.7) |

| Psychiatrist | 9 (7.5) |

| Availability of palliative care servicesa | n = 120 (84.5) |

| Outpatient consultation | 93 (77.5) |

| Home hospice (not affiliated with pediatric hospital) | 70 (58.3) |

| Inpatient consultation—day hours only | 66 (55) |

| Inpatient consultation—24/7 coverage | 53 (44.2) |

| Consultation care—home setting | 51 (42.5) |

| Home hospice (affiliated with pediatric hospital) | 22 (18.3) |

| Other | 17 (14.2) |

| Palliative care inpatient unit at pediatric hospital | 9 (7.5) |

| AYA program | n = 116 (81.7) |

| No | 48 (41.4) |

| Yes | 41 (35.3) |

| Not sure | 27 (23.3) |

| Pain team coverage | n = 116 (81.7) |

| Separate from palliative care service | 64 (55.2) |

| Part of palliative care service | 26 (22.4) |

| No pain team | 26 (22.4) |

More than one response allowed for this question.

PPC, pediatric palliative care.

Palliative care team structure

Respondents described interdisciplinary PPC team composition as reported in Table 2. Team composition primarily included clinicians, such as physicians and nurse practitioners, social workers, nurses and nurse case managers, chaplains, and administrative staff. Additional roles described as “other” included: music therapists; integrative medicine practitioners; research coordinators and bereavement coordinators; educators; respite volunteers; and patient navigators.

Palliative care team services

Referrals to palliative care teams occurred in several ways, including in-person conversation (79%), phone call (73%), electronic medical order (63%), email (34%), and written order (11%).

Palliative care services for children and adolescents with cancer included outpatient consultation services during day hours (78%), inpatient consult availability limited to day hours (55%), home consultation services (43%), and 24/7 inpatient consultation services (44%). Only 8% of responding sites offered a designated, specific inpatient palliative care unit in the hospital setting. Pediatric home hospice services were affiliated through the hospital at 18% of sites and were available in the local community, but not affiliated with the pediatric hospital at 58% of sites. Nearly one quarter (24%) of responding sites reported that neither hospital nor local community hospice services were available for their patients.

The PPC team served also as the pain team at 22% of sites, was separate from the pain team at 55% sites, and served in a setting where there was not a designated pain team at 22% sites.

Availability and access to specific palliative care services such as symptom management, advance care planning, integrative therapies, counseling, and support services for children with cancer are provided as Table 3.

Table 3.

Services Incorporated into Palliative Care Team Plans

| Service (N = 120) | Weighted average | Available, infrequently used, n (%) | Availble, sometimes used, n (%) | Available, often used, n (%) | N/A, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child-life services | 2.71 | 6 (5) | 19 (16) | 83 (69.8) | 11 (9.2) |

| Symptom management | 2.63 | 8 (6.7) | 28 (23.3) | 82 (68.3) | 2 (1.7) |

| Chaplain support | 2.49 | 11 (9.4) | 35 (29.9) | 65 (55.6) | 6 (5.1) |

| Art therapy | 2.49 | 4 (3.5) | 33 (28.4) | 43 (37) | 36 (31) |

| Advance care planning | 2.46 | 10 (8.5) | 41 (34.8) | 63 (55.4) | 4 (3.4) |

| Bereavement services | 2.44 | 10 (8.6) | 36 (31) | 54 (46.6) | 16 (13.8) |

| Music therapy | 2.43 | 6 (5.1) | 39 (33) | 44 (37.3) | 29 (24.6) |

| Pet therapy | 2.43 | 9 (7.8) | 32 (27.6) | 47 (40.5) | 28 (24.1) |

| Individual counseling | 2.19 | 15 (12.6) | 53 (44.5) | 35 (29.4) | 16 (13.4) |

| Family counseling | 2.18 | 17 (14.5) | 43 (36.8) | 34 (29.1 | 23 (19.7) |

| Interventions following treatment completion/survivorship | 2.14 | 17 (15) | 33 (29.2) | 28 (24.8) | 35 (30) |

| Massage therapy | 2.12 | 12 (10.5) | 27 (23.7) | 19 (16.7) | 56 (49.1) |

| Counseling for siblings | 2.10 | 20 (17) | 49 (41.5) | 30 (25.4) | 19 (16.1) |

| Patient support group | 2.00 | 14 (12.4) | 31 (27.4) | 14 (12.4) | 54 (47.8) |

| Reiki or healing touch | 1.89 | 16 (14.2) | 20 (17.7) | 11 (9.7) | 66 (58.4) |

| Acupuncture | 1.82 | 13 (11.5) | 22 (19.5) | 72 (63.7) | 72 (63.7) |

| Biofeedback or visual imagery | 1.82 | 18 (15.9) | 37 (32.7) | 7 (6.2) | 51 (45.1) |

Timing and triggers for palliative care introduction

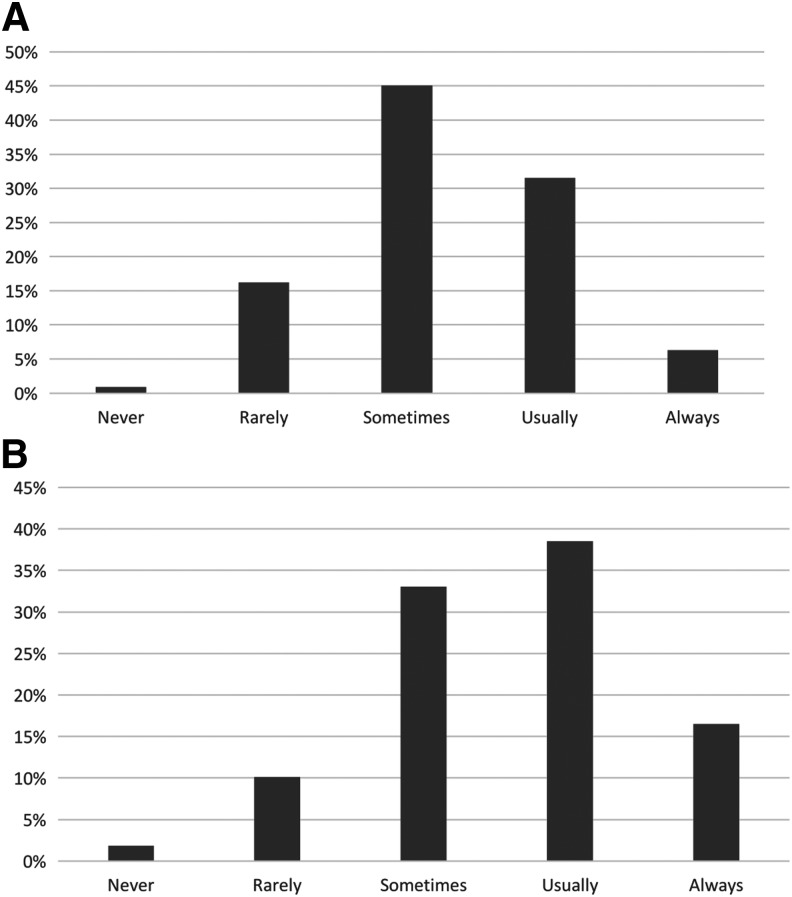

Survey respondents stated that youth with cancer and their families were introduced to palliative care concepts, such as symptom management, compassionate and honest communication, and goals of care, regardless of their disease state: never 1%, rarely 16%, sometimes 46%, usually 32%, and always 6%. Figure 1 provides a histogram conveying survey responses to the frequency of palliative care introduction for children and families with cancer. Using the proportional odds model, there was no significant association between frequency of introduction to palliative care concepts and geographic location (p = 0.52), number of referrals (p = 0.88), or programmatic years in service (p = 0.18).

FIG. 1.

Frequency of access to palliative care concepts and end-of-life communication for children with cancer and their families. (A) Palliative care concepts introduced regardless of disease status. (B) Receipt of developmentally appropriate end-of-life communication.

Time point of introduction to palliative care principles was at diagnosis 8%, at disease-specific time points such as relapse 41%, and without a clear uniform time 51%. Twenty-nine respondents provided free text clarifying responses. Free text responses depicted that the timing of palliative introduction was “prognosis” specific (48%), “late” (17%), “at end of life” (17%), provider dependent (15%), and psychosocial initiated (3%). Over half (56%) of respondents reported that their sites use automatic “triggers” (specific diagnoses or disease experiences such as relapse or Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant) to prompt a subset of palliative care referrals (Table 4). The odds that palliative care principles were introduced in the setting of pre-established trigger diagnoses or prognoses were 3.41 (1.52, 7.69) times greater than if there is no trigger (p < 0.003).

Table 4.

Palliative Care Introduction Time Points and Triggers

| Time points for palliative care concept presentation | n = 111 |

| No uniform times | 56 (50.5%) |

| At disease-specific time point (e.g., relapse) | 46 (41.4%) |

| At diagnosis | 9 (8.1%) |

| Triggers for automatic consideration of palliative carea | n = 91 |

| No trigger diagnoses | 40 (44%) |

| Difficult to manage symptoms or high symptom burden | 34 (37.4%) |

| Diagnosis of refractory disease | 30 (32%) |

| Diagnosis of recurrent disease | 28 (30.8%) |

| Upon consultation to bone marrow transplant | 28 (30.8%) |

| Patients needing discussion of advanced directives | 22 (24.2%) |

| Difficult social situation or family having difficulty coping | 21 (23.1%) |

| “Low likelihood” of anticipated event-free survival above certain percent | 20 (22%) |

| Phase I trial referral | 8 (8.8%) |

| New cancer diagnosis (any type) | 4 (4.4%) |

More than one response allowed for this question.

Communication of palliative care principles

As displayed in Figure 1, respondents stated that children or adolescents with cancer and their families receive developmentally appropriate communication about end of life: never (2%); rarely (10%); sometimes (33%); usually (38%); and always (17%).

Prognosis is discussed by multiple team members, including primary oncologist (98%), palliative care physician (41%), nurse practitioner (34%), social worker (12%), and psychologist (5%). Advance directives and decisions regarding life-sustaining interventions are discussed by the primary oncologist (90%), palliative care physician (77%), nurse practitioner (49%), social worker (45%), psychologist (16%), chaplain (17%), or no one (2%).

Developmentally relevant education materials about palliative principles are available in the form of written materials (77%), websites (30%), videos (16%), and not available (24%). When communication resources were reported to be available, these were only available in English (81%) or Spanish (59%).

Palliative care education and research

Less than a quarter (21%) of respondents from centers with pediatric oncology fellowship programs reported a required rotation in PPC for their pediatric hematology/oncology fellows; over half stated their fellows did not rotate with PPC at all.

Academic PPC scholarship was prevalent. Seventy-eight percent of respondents reported at least some research at their center, including clinical (53%), quality improvement (48%), psychosocial (41%), health services (36%), and pharmaceutical (3%) research.

Perceived barriers to palliative care

A summary of perceived barriers to palliative care involvement comparing centers with and without pediatric oncology fellowship programs is provided in Table 5. Lack of palliative care availability, lack of insurance coverage, and patient perception of palliative care were not selected as “the most important barrier” by any respondent. The perception that pediatric oncologists are providing adequate care was the most common barrier to referrals across settings. Late referrals were second highest barrier at centers with pediatric oncology fellowship training programs. Centers without a fellowship program tended to emphasize barriers regarding primary provider perception of lack of benefit more than lack of knowledge on palliative care (Table 5).

Table 5.

Perceived Barriers to Palliative Care Consultation

| Centers with PPC services with a pediatric oncology fellowship training program (n = 58) | Centers with a PPC service without a pediatric oncology fellowship training program (n = 33) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived barrier | Ever a barriera(%) | Most important barrier (%) | Ever a barriera(%) | Most important barrier (%) |

| Some pediatric oncologists believe that they provide adequate palliative care | 82 | 30 | 70 | 27 |

| Late referrals (patient's disease is too advanced to benefit significantly from referral) | 78 | 22 | 73 | 9 |

| Some pediatric oncologists do not perceive a benefit in incorporating palliative care | 65 | 10 | 64 | 21 |

| Some pediatric oncologists do not believe their patients need palliative care | 63 | 12 | 67 | 9 |

| Parental negative perception of palliative care | 60 | 5 | 48 | 12 |

| Some pediatric oncologists are not aware of the scope of palliative care services | 52 | 8 | 58 | 0 |

| Some pediatric oncologists are not aware of the benefits of palliative care | 45 | 2 | 42 | 15 |

| Inadequate palliative care staffing | 33 | 5 | 39 | 6 |

| Patient negative perception of palliative care | 28 | 0 | 27 | 0 |

| Lack of palliative care availability in the outpatient, home, and hospice setting | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lack of insurance coverage | 3 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

More than one response allowed for this question.

Perceived palliative care capacity

Capacity of the PPC services compared with demand was described as: capacity lower than demand (49%), capacity matches demand (33%), and capacity higher than demand (18%). Using the generalized logistics model, there was no significant association between perceived capacity and geographic location (p = 0.75). Using the proportional odds model, there was no significant association between perceived capacity and the number of referrals (p = 0.97) or perceived capacity and programmatic years in service (p = 0.22).

Discussion

The survey results reveal variable practices suggesting opportunities to implement the standard for PPC for children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer in the future. Although a recent national PPC inventory reported cancer as the most common PPC diagnostic category (24.5% of all PPC referrals),13 access to an interdisciplinary PPC team and the services offered by that team for children with cancer are divergent.

Some centers have predetermined certain diagnoses, prognoses, care escalation metrics, lengths of stay, or readmission rates which “trigger” the automatic consideration of a palliative care consultation. Trigger diagnosis have prospectively been found to be feasible and acceptable for early palliative care consultation for children with malignancies.14 Triggers may be one way to assess PPC need and services, although each site must balance their available personnel with their patient population. Less than half of responding centers have specific diagnostic or time point (pretransplant or intensive care admission) triggers to facilitate inclusion of palliative care teams. When referral triggers are in place, the odds that palliative care principles are introduced is 3.41 times more likely than when triggers are not in place (p = 0.003). The majority of triggers was grounded in events such as relapse, preparation for bone marrow transplant, progression, or new metastatic disease. Triggers for considering a palliative care consultation notably lacked screening for high symptom burden or psychosocial vulnerability. Tools and instruments, which assess for biomedical and psychosocial domains, are available to help screen children with palliative needs.15,16

While prognosis is primarily discussed by the pediatric oncologist (98%) rather than the palliative care physician (41%), advance care planning and decisions regarding life-sustaining interventions involve the interdisciplinary team to an increasing extent. This speaks to the opportunity for primary level palliative care as a synergistic, partnered, interdisciplinary communication approach for prognosis and goals of care conversations.17 PPC teams discussing prognosis can help open doors to communication. The new adolescent young adult (AYA) advance care planning tool (Voicing My Choices™) helps foster these conversations and can be introduced by any member of the team.18

Tangible needs revealed by the survey include the stark need for more developmentally relevant educational materials, especially in different languages, and attentiveness to AYA-specific palliative care programs in setting of unique psychosocial needs of this cohort. The AYA cohort is known to have poorer prognostic outcomes19 and yet few sites described having an AYA program (35%).

The survey revealed gaps in palliative care service availability, as palliative care practitioners tended toward availability during day hours on a consultant basis rather than a 24/7 model. With a known workforce shortage in palliative care and yet the reality that many palliative care needs occur after traditional work hours,20 the palliative workforce may benefit from creative interventions such as flexible work hours for palliative care providers or after-hours telehealth palliative access.21,22 The availability of palliative care designated beds was a rarity as was the availability of home hospice services.

The main perceived barrier to palliative care subspecialist consultation was oncology providers' perceptions that the oncologist was already providing palliative care. This finding warrants further education of providers on the interdisciplinary services and care skillset uniquely available through palliative care teams. This finding also compels ongoing commitment to train oncologists in primary palliative care principles as part of fellowship formation and ongoing professional development. The standing barrier to palliative care integration was not patient resistance or concern for family discomfort, but was instead provider discomfort.

Capacity to attend to palliative care needs for children with cancer was notably lower than the demand for palliative care services. This speaks to expanding the workforce through training tracks.23

While this study is informative in providing an overview of the palliative care services for children and families with cancer, there are noted limitations. Although programs were requested to provide one respondent per site, this could not be guaranteed due to anonymity. The response rate could not be feasibly calculated due to overlapping membership on listservs (many respondents were listed in multiple listserv groupings) and thus the denominator of total surveys distributed is unknown. The survey relied on self-report rather than program investigation and, thus, there could be an inherent bias in over- or underreporting the quality or range of services offered. Practice of nonresponders may vary from that of responders.24 Interesting and important future research would be to link center report with actual patient and proxy experience at those centers.

This overview survey raises topics worthy of future in-depth exploration of topical areas such as perceived barriers to palliative care; partnering of pain services, integrative therapy services, and palliative care as part of comprehensive care for children with cancer; programmatic funding for sustainable impact; and improvement metrics in offering not just palliative care, but comprehensive and quality palliative care.

The empirical evidence documenting benefit of palliative care subspecialist partnership in caring for children with cancer and their families continues to accumulate. As palliative care programs mature and evolve, the value of palliative care for these vulnerable populations is anticipated to progress toward a standard of care. As a biological treatment protocol for a child stands as a universal approach regardless of treatment location or resource setting, the opportunity for palliative needs assessment and intervention may benefit from standardized implementation.

Appendix 1. Survey Questions and Response Choices

Newly Published Psychosocial Standards of Care: What is Needed for Full Implementation?

This short anonymous survey will help us learn about the palliative and bereavement services that are provided at your center. This information is important in facilitating the delivery of psychosocial care that is consistent with newly published psychosocial standards of care in pediatric oncology.

We value your thoughtful answers. If you do not have time/knowledge to complete the survey, please forward the link to a provider who is knowledgeable about palliative and bereavement care services at your center. The questionnaire should take about 10 minutes. You can save and return later.

This survey is voluntary. We are greatly appreciative of you sharing your valuable time so that we can work toward enhancing quality psychosocial standards of care for all children with cancer and their family members.

-

1. Your Profession

a. Oncologist

b. Palliative Care Physician

c. Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant

d. Nurse

e. Social Worker

f. Psychologist

g. Chaplain

h. Hospital Administrator

i. Child-life specialist

j. Other (please specify)

-

2. From where did you receive this survey?

a. AAP Section on Hospice and Palliative Care List-Serve

b. Pediatric Palliative Care Network

c. Referred from a local Pediatric Palliative Care Team

d. SIOP PODC Palliative Care Working Group

e. AAHPM Palliative Care SIG Message

f. ASPHO Palliative Care Working Group Message

g. Other

-

3. In what city do you work?

a. [Open-response]

-

4. Approximately how many pediatric/adolescent oncology cases are seen at your cancer center per year?

a. 1–50

b. 51–100

c. 101–150

d. >150

-

5. In which area(s) do you work?

a. Inpatient

b. Outpatient Clinic

c. Hospice

d. Other (please specify)

-

6. Does your cancer center offer pediatric palliative care services to children and adolescents?

a. Yes, my center offers a pediatric palliative care program

b. Yes, my center offers an adult palliative care program which covers pediatric palliative care needs

c. Yes, my center has access to a pediatric palliative care provider, but does not have a full pediatric palliative care program

d. No, my center does not have pediatric palliative care services (Thank you for participating)

-

7. Which specific palliative care services for children and/or adolescents are available at our cancer center? Please check all that apply.

a. Inpatient consultation, day hours only

b. Inpatient consultation, 24/7 coverage

c. Outpatient consultation

d. Palliative care inpatient unit

e. Consultation care in home setting

f. Home hospice affiliated through the hospital

g. Home hospice not affiliated through the hospital

h. Other (please specify)

-

8. Please indicate which services are incorporated into palliative care plans for children and families. Please check all that apply. [Options: Available, but infrequently used; Available, sometimes used; Available, often used; N/A]

a. Symptom Management

b. Advance Care Planning

c. Chaplain Support

d. Individual Counseling

e. Family Counseling

f. Counseling for Siblings

g. Child-life Services

h. Bereavement Services

i. Interventions following treatment completion/Survivorship

j. Massage Therapy

k. Music Therapy

l. Art Therapy

m. Acupuncture

n. Reiki or Healing Touch

o. Biofeedback or Visual Imagery

p. Pet Therapy

q. Patient Support Group

r. Other (please specify)

-

9. Please indicate whether these providers/roles are available to patients with cancer in your center as part of the palliative care team. [Options: Part of Palliative Care Team; Do Not Know)

a. Physician

b. Physician Assistant

c. Nurse Practitioner

d. Registered Nurse

e. Social Worker

f. Chaplain

g. Pharmacist

h. Psychologist

i. Psychiatrist

j. Child-life Specialist

k. Massage Therapist

l. Art Therapist

m. Case Manager

n. Other (please specify)

-

10. When was your site's pediatric palliative care team established?

a. <5 years ago

b. 6–10 years ago

c. 11–20 years ago

d. >20 years ago

e. Not sure

-

11. Does your site have a pain team?

a. Yes, the pain service is part of the palliative care service

b. Yes, the pain service is separate from the palliative care service

c. No, we do not have a dedicated pain service

-

12. Does your medical center have an adolescent/young adult (AYA) program from patients with cancer?

a. Yes (please describe what specific AYA services are provided)

b. No

c. Not sure

-

13. How does the capacity of pediatric palliative care services compare to the demand for pediatric palliative care services at your center?

a. Capacity significantly higher than demand

b. Capacity somewhat higher than demand

c. Capacity matches demand

d. Capacity somewhat lower than demand

e. Capacity significantly lower than demand

-

14. Do pediatric oncology fellows rotate with the palliative care team?

a. Yes, as an elective

b. Yes, as a required rotation

c. No, the fellows do not rotate with the palliative care team

d. Not relevant, my setting does not have pediatric oncology fellows

e. Other (please specify)

-

15. Does the institution conduct palliative supportive care research? (Select all that apply)

a. Yes, clinical palliative care research

b. Yes, pharmaceutical palliative care research

c. Yes, psychosocial palliative care research

d. Yes, quality improvement palliative care research

e. Yes, health services and outcomes palliative care research

f. No

g. Not sure

h. Comments [open-response]

-

16. How often are youth and families in your pediatric cancer program introduced to palliative care concepts (e.g. symptom assessment and intervention; compassionate and honest communication; elicitation of decisional preferences in the form of advanced care planning) regardless of their disease status?

a. Never

b. Rarely

c. Sometimes

d. Usually

e. Always

-

17. At what time point are palliative care concepts presented to patients and families throughout the disease process?

a. At diagnosis

b. At disease-specific time points (e.g. relapse)

c. No uniform times

d. Other (please specify)

-

18. Who discusses prognosis at your center? (Select all that apply)

a. Primary oncologist

b. Palliative care physician

c. Nurse practitioner or Physician Assistant

d. Social worker

e. Psychologist

f. Psychiatrist

g. Chaplain

h. Other (please specify)

-

19. Who discusses advance directives/decisions regarding life-sustaining interventions? (Select all that apply)

a. Primary oncologist

b. Palliative care physician

c. Nurse practitioner or Physician Assistant

d. Social worker

e. Psychologist

f. Psychiatrist

g. Chaplain

h. Other (please specify)

-

20. What diagnoses or situations trigger automatic consideration of palliative care consults at your center as a standard of care? (Choose all that apply)

a. New cancer diagnosis (any type)

b. New cancer diagnosis with anticipated event free survival less than a certain percentage

c. Upon consultation to bone marrow transplant

d. When referred to a phase I trial

e. Diagnosis of recurrent disease

f. Diagnosis of refractory disease

g. Difficult-to-manage symptoms or high symptom burden

h. Difficult social situation or family having difficulty coping

i. Patients needing discussion of advance directives

j. We have no trigger diagnoses

-

21. How are palliative care referrals made? (Check all that apply)

a. In-person conversation

b. Phone call

c. Email request

d. Written prescription

e. Electronic order

f. Other (please specify)

-

22. Please indicate which barriers you encounter when referring to the palliative care service (check all that apply):

a. Some pediatric oncologists do not perceive a benefit in incorporating palliative care

b. Some pediatric oncologists are not aware of the benefits of palliative care

c. Some pediatric oncologists are not aware of the scope of palliative care services

d. Late referrals (patients' disease is too advanced to benefit significantly from referral)

e. Some pediatric oncologists believe that they provide adequate palliative care

f. Some pediatric oncologists do not believe that their patients need palliative care

g. Inadequate palliative care suffering

h. Lack of insurance coverage

i. Patient negative perception of palliative care

j. Parental negative perception of palliative care

k. Other (please specify)

-

23. Using the same list as above, please select the single most important barrier to referral to the palliative care service (choose only one):

a. Some pediatric oncologists do not perceive a benefit in incorporating palliative care

b. Some pediatric oncologists are not aware of the benefits of palliative care

c. Some pediatric oncologists are not aware of the scope of palliative care services

d. Late referrals (patients' disease is too advanced to benefit significantly from referral)

e. Some pediatric oncologists believe that they provide adequate palliative care

f. Some pediatric oncologists do not believe that their patients need palliative care

g. Inadequate palliative care suffering

h. Lack of insurance coverage

i. Patient negative perception of palliative care

j. Parental negative perception of palliative care

k. Other (please specify)

-

24. When necessary, do patients and families at your center receive developmentally appropriate communication about end of life appropriate for the patient's learning (meaning: communication and care appropriate for the patient's learning style and physical ability to interact)?

a. Never

b. Rarely

c. Sometimes

d. Usually

e. Always

-

25. Please select which developmentally appropriate educational materials are available to patients and families at our center.

a. Written materials

b. Videos

c. Websites

d. No developmentally appropriate educational materials are provided for patients and families at my center

e. Other (please specify)

-

26. In what language(s) are these materials available?

a. English

b. Spanish

c. French

d. Italian

e. German

f. Hebrew

g. Chinese

h. Greek

i. Russian

j. Farsi

k. I do not know

l. Other language (please specify)

-

27. After a patient dies, does your oncology team have a policy in place to routinely asses bereavement needs of families?

a. No

b. Yes

-

28. Does your program use a formal bereavement risk assessment tool? (e.g. Bereavement Risk Assessment Tool)?

a. Yes

b. No

c. I do not know

-

29. Does your oncology team routinely assess bereavement needs of families?

a. Never

b. Rarely

c. Sometimes

d. Usually

e. Always

-

30. After a patient dies, does anyone from the palliative team routinely assess bereavement needs of families?

a. Never

b. Rarely

c. Sometimes

d. Usually

e. Always

-

31. Do staff deliver bereavement care after a child's death? (If never, thank you for participation)?

a. Never

b. Rarely

c. Sometimes

d. Usually

e. Always

-

32. Please select all the forms of direct bereavement services that are systematically offered at your center (check all that apply):

a. Phone call from a healthcare team member

b. Phone call from a bereavement coordinator

c. Literature, child grief

d. Literature, adult grief

e. Cards

f. Attend service/funeral

g. Anniversary cards

h. Counseling in person

i. Referral to a counselor/therapist

j. Referral to a support group

k. Other (please specify)

-

33. Does the person who contacts bereaved parent(s) personally know the family?

a. Never

b. Rarely

c. Sometimes

d. Usually

e. Always

-

34. What is the discipline of the person who contacts family members? (Check all that apply)

a. Physician

b. Nurse practitioner/Physician assistant

c. Nurse

d. Social Worker

e. Psychologist

f. Psychiatrist

g. Chaplain/Pastoral care provider

h. Bereavement counselor

i. Other (please specify)

-

35. How long does the bereavement care in your program continue for?

a. At the time of death only

b. First month after death

c. 2–6 months after death

d. 7–12 months after death

e. 1–2 years after death

f. >2 years after death

36. Is there anything else you would like to add about palliative and bereavement care offered by your program? [open response]

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Chris Feudtner, Dr. Justin Baker, Dr. Brian Carter, Dr. Emma Jones for assistance with survey distribution. The authors also wish to thank Dr. Joanne Wolfe for her thoughtful review of the survey instrument.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Feudtner C, Womer J, Augustin R, et al. : Pediatric palliative care programs in children's hospitals: A cross-sectional national survey. Pediatrics 2013;132:1063–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field MJ, Behrman RE. Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families: When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care. www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en (Last accessed on July14, 2017)

- 4.Rosenberg AR, Oreliana L, Ullrich C, et al. : Quality of life in children with advanced cancer: A Report from the PediQUEST Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52:243–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weaver MS, Reeve BB, Baker JN, et al. : Concept-elicitation phase for the development of the pediatric patient-reported outcome version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Cancer 2016;122:141–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaye EC, Brinkman TM, Baker JN: Development of depression in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: A multi-level life course conceptual framework. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:2009–2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiener L, Viola A, Koretski J, et al. : Pediatric psycho-oncology care: Standards, guidelines, and consensus reports. Psychooncology 2015;24:204–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weaver MS, Heinze KE, Kelly KP, et al. : Palliative care as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62:S829–S833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiener L, Kazak AE, Noll RB, et al. : Standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families: An introduction to the special issue. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62 Suppl 5:S419–S424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scialla MA, Canter KS, Chen FF, et al. : Implementing the psychosocial standards in pediatric cancer: Current staffing and services available. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:e26634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillman D, Smyth J, Christian L: Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agresti A: Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers MM, Kirch RA: CAPC. The Palliative Pulse. July 2017. Spotlight on Pediatric Palliative Care: National Landscape of Hospital-Based Programs, 2015–16. https://palliativeinpractice.org/palliative-pulse/palliative-pulse-july-2017/spotlight-pediatric-palliative-care-national-landscape-hospital-based-programs-2015-2016 (Last accessed July14, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmood L, Casey D, Dolan JG, et al. : Feasibility of early palliative care consultation for children with high-risk malignancies. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:1419–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergstraesser E, Hain RD, Pereira JL: The development of an instrument that can identify children with palliative care needs: The Paediatric Palliative Screening Scale (PaPaS Scale): A qualitative study approach. BMC Palliative Care 2013;12:1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen IT, Cochran D, Lomax E, et al. : Validity and reliability of pediatric palliative care assessment tool. Peds Anesthesia 2007 Annual Meeting Scientific Report SR30. www2.pedsanesthesia.org/meetings/2007annual/syllabus/Scientific_Reports/SR30-Cohen.pdf (last accessed July14, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman DE, Meier DE: Identifying patients in need of palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: A Consensus Report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2011;14:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zadeh S, Pao M, Wiener L: Opening end-of-life discussions: How to introduce Voicing My Choices™, an advance care planning guide for adolescent and young adults. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:591–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattano L, Nachman J, Ross J: Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15–29 Years of Age, Including Incidence and Survival: 1975–2000 (NIH Pub No 06-5767). Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meier DE: Increased Access to Palliative Care and Hospice Services: Opportunities to Improve Value in Health Care. Milbank Q 2011;89:343–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winegard B, Miller EG, Slamon NB: Use of telehealth in pediatric palliative care. Telemed J E Health. 2017;11:938–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradford N, Irving H, Smith AC, et al. : Palliative care afterhours: A review of phone support services. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2012;29:141–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiener L, Weaver M, Bell C, Sansom-Daly U: Threading the cloak: Palliative care education for care providers of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Clin Oncol Adolesc Young Adults 2015;5:1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VanGeest J, Johnson T, Welch V: Methodologies for improving response rates in surveys of physicians: A systematic review. Eval Heal Prof 2007;30:303–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]