Abstract

Brain stimulation is increasingly viewed as an effective approach to treat neuropsychiatric disease. The brain's organization in distributed networks suggests that the activity of a remote brain structure could be modulated by stimulating cortical areas that strongly connect to the target. Most connections between cerebral areas are asymmetric, and a better understanding of the relative direction of information flow along connections could improve the targeting of stimulation to influence deep brain structures. The hippocampus and amygdala, two deep-situated structures that are crucial to memory and emotions, respectively, have been implicated in multiple neurological and psychiatric disorders. We explored the directed connectivity between the hippocampus and amygdala and the cerebral cortex in patients implanted with intracranial electrodes using corticocortical evoked potentials (CCEPs) evoked by single-pulse electrical stimulation. The hippocampus and amygdala were connected with most of the cortical mantle, either directly or indirectly, with the inferior temporal cortex being most directly connected. Because CCEPs assess the directionality of connections, we could determine that incoming connections from cortex to hippocampus were more direct than outgoing connections from hippocampus to cortex. We found a similar, although smaller, tendency for connections between the amygdala and cortex. Our results support the roles of the hippocampus and amygdala to be integrators of widespread cortical influence. These results can inform the targeting of noninvasive neurostimulation to influence hippocampus and amygdala function.

Keywords: : effective connectivity, electrical brain stimulation, evoked potentials, medial temporal lobe, neurostimulation

Introduction

Our understanding of the organization of the human brain has been transformed by recent progress in brain mapping methodologies, together with the introduction of graph theory providing a framework to analyze and interpret data yielded by these techniques (Sporns, 2012). In this framework, distributed networks involving multiple cerebral structures perform the neural computations underlying cognition and behavior. Neurological and psychiatric diseases are also beginning to be conceived of in terms of network pathology (Castellanos et al., 2013), and modulating the activity of these networks through noninvasive brain stimulation is a promising therapeutic avenue (Fregni and Pascual-Leone, 2007). Even structures buried deep in the brain, previously thought to be inaccessible to transcranial magnetic or electrical stimulation, could potentially be targeted by delivering the stimulation to cortical areas with which these structures are strongly connected (Fox et al., 2014).

The hippocampus and amygdala, two structures of the medial temporal lobe, play key roles in declarative memory and emotions, respectively, and have been implicated in many neurological and psychiatric diseases. The highly integrative functions of these structures call for their embedding in distributed large-scale neural networks, including wide expanses of cerebral cortex. Anatomical tracer studies in animals and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and magnetic resonance tractography studies in humans indeed point toward such an organization (Kahn et al., 2008; Lavenex and Amaral, 2000; LeDoux, 2007; Powell et al., 2004; Roy et al., 2009). Although statistical models based on fMRI data can estimate the direction of interactions within neural networks, there remains debate regarding the interpretation of these metrics (David et al., 2008; Friston et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2011; Webb et al., 2013). Thus, the directed connectivity of the hippocampus and amygdala with the cerebral cortex remains incompletely explored in the human brain.

This is an important issue in light of the therapeutic potential of noninvasive brain stimulation, as not all neural connections are reciprocal: detailed anatomical studies in primates reveal that a considerable proportion of corticocortical projections are either unidirectional (i.e., unreciprocated) or asymmetrical in weight (Markov et al., 2013, 2014). Corticocortical evoked potentials (CCEPs), the responses evoked at a distance from focal electrical stimulation of the brain, probe the directed connectivity of the human brain with high spatiotemporal resolution (Keller et al., 2014b). CCEP-based connectivity corresponds to functional connectivity based on resting fMRI (Keller et al., 2011) and to structural connectivity assessed by diffusion tensor imaging (Conner et al., 2011). Importantly, CCEPs reveal the direction and weight of connections between cortical areas. Indeed, our laboratory recently reported widespread connectional asymmetry in the human neocortex using CCEPs (Entz et al., 2014; Keller et al., 2014a).

Here, using systematic CCEP mapping in a large cohort of epilepsy patients implanted with intracranial electroencephalogram (iEEG) electrodes, we explore the connections that the hippocampus and amygdala establish with the rest of the cerebral cortex. Our results provide insight into the functional integration of these structures in the human brain's large-scale neuronal networks.

Methods

Patients

We included patients who were monitored with iEEG electrodes (either combinations of subdural and depth electrodes or stereo-EEG depth electrodes; Ad-Tech, Racine, WI, and Integra, Plainsboro, NJ; subdural electrodes: 3 mm platinum disks with 10 mm interelectrode spacing; depth electrodes: 2.5 mm platinum cylinders with 5 mm interelectrode spacing) at the North Shore-LIJ Health System between March 2010 and June 2014, had undergone single-pulse electrical stimulation, had at least a pair of neighboring electrodes in the hippocampus or amygdala, and did not have any overtly visible brain lesion, such as extensive cortical dysplasia, tumor, or stroke. Twenty-one patients (10 women) met the criteria: 9 had bilateral electrode implantations and 1 was later implanted again with subdural electrodes over one hemisphere (Table 1). Electrodes were implanted for clinical purposes only, without reference to this study. The study followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local institutional review board. Patients provided written informed consent.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Gender | Age | Seizure onset zone | Implant type | Hemisphere |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 22 | L TO | Subdural | L |

| F | 25 | L TM | Subdural | L |

| M | 15 | L TP, R T, R F | Subdural | L > R |

| F | 40 | L TM | Subdural | L |

| M | 60 | L TL | Subdural | L |

| F | 36 | L TL, L TM | Subdural | L |

| F | 25 | L TM | Subdural | L |

| M | 22 | R F DL, R T | Subdural | R |

| F | 49 | R TM, L TM | Stereo-EEG | Both |

| M | 52 | L TM, R TM | Stereo-EEG | Both |

| M | 35 | R TM | Stereo-EEG | Both |

| F | 19 | R TL, L TL | Stereo-EEG | Both |

| M | 42 | L TM, L F | Stereo-EEG | Both |

| M | 25 | L TM, L TL | Stereo-EEG | Both |

| (same patient) | Subdural | L | ||

| M | 40 | L T | Stereo-EEG | L |

| M | 30 | R T | Subdural | R |

| M | 41 | L TM | Stereo-EEG | Both |

| M | 45 | L TM | Subdural | L |

| F | 34 | L TM | Subdural | L |

| F | 20 | L F DM | Stereo-EEG | Both |

| F | 48 | L TM | Subdural | L |

T, temporal; F, frontal; P, parietal; O, occipital; M, medial; L, lateral; D, dorsal; EEG, electroencephalogram.

Electrode localization

Intracranial electrodes were localized using the iELVis toolbox (http://ielvis.pbworks.com; Groppe et al., 2017). In brief, we coregistered high-resolution postimplantation computed tomography (CT) and MRI scans with a preimplantation 3-T MRI scan. We then identified intracranial electrodes on the CT scan using BioImage Suite (http://bioimagesuite.org). We used FreeSurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu; Fischl, 2012) to segment the white matter and deep gray matter structures, reconstruct the pial surface, parcellate the neocortex according to gyral anatomy, and register the pial surface of individual patients onto a standardized atlas (Desikan et al., 2006). Depth electrodes located in the hippocampus or amygdala provided the basis for patient selection. We excluded electrodes that were not located in the hippocampus, amygdala, or cortical gray matter according to the Freesurfer segmentation. The remaining electrodes were projected to the pial surface. To graphically represent the location of the bipolar stimulating and recording electrode pairs (cf. “CCEP recordings” section) on the brain surface, we computed the point lying halfway between the two electrodes (Euclidean distance) and then projected that point to the pial surface. Using intraoperative photographs as the gold standard, electrode localization was accurate to within 3 mm in most cases (Dykstra et al., 2012; Groppe et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2012).

CCEP recordings

iEEG signals were referenced to a vertex screw or subdermal electrode, filtered (high-pass 0.1 Hz, low-pass 40% of the sampling rate), digitized at 500–2000 Hz, and stored for offline analysis by XLTEK EMU128FS or NeuroLink IP 256 systems (Natus Medical, Inc., San Carlos, CA).

We performed CCEP mapping as previously described (Entz et al., 2014; Keller et al., 2011, 2014a). In brief, mapping was performed toward the end of the patients' stay in the epilepsy monitoring unit, when seizures had been observed and antiepileptic drugs had been reinstated. Patients were awake during CCEP mapping. Single-pulse bipolar electrical stimulation (20 biphasic pulses with each phase lasting 200 μsec) was delivered at 0.5 or 1 Hz to pairs of neighboring electrodes (S12 stimulator; Grass Technologies, Warwick, RI). Our laboratory previously found no influence of these two differing interstimulus intervals on CCEPs (Entz et al., 2014; Keller et al., 2014a). All stimulations to the hippocampus or amygdala were delivered through depth electrodes that lay directly in those structures, as opposed to subdural electrodes contacting the cortex of the medial temporal lobe.

Neuronal activation in response to electrical stimulation is influenced by current density through the stimulation electrodes. Most of the stimulating current occurs at the electrode's edge, at the interface with the insulator, meaning that electrode perimeter, rather than surface, influences current density (Shannon, 1992). Here, subdural electrodes were disks whose exposed surface had a diameter of 2.3 mm, corresponding to a perimeter of 7.2 mm, whereas depth electrodes were cylinders with a diameter of 1.12 mm, giving a total perimeter (adding the upper and lower perimeters) of 7.04 mm. These two perimeters being almost identical, current intensity was the main determinant of current density in subdural versus depth electrodes. Current intensity was initially set to 10 mA for both subdural and depth electrodes; after the first 10 patients, it was reduced to 4–5 mA in depth electrodes to reduce the risk of triggering seizures. We compared our observations in those two patient subgroups to assess the impact of this change on our findings.

We performed all iEEG and CCEP analyses using custom MATLAB scripts. We first converted iEEG recordings to bipolar derivations identical to those used for stimulation. One second iEEG epochs from −200 to +800 msec relative to the electrical stimulus were baseline corrected (−200 to −25 msec period) and averaged to yield the CCEP traces. These traces were visually inspected, and derivations contaminated by stimulator artifacts or 60-Hz noise were rejected. We then converted the mean voltage traces into t-scores by dividing them by the standard error of the mean at each time point (Groppe et al., 2011).

Deriving connectivity matrices from CCEPs

CCEPs typically consist of a series of voltage deflections of alternating polarity. Here, we focused on the earliest responses (10–50 msec poststimulus, the first 10 msec being discarded because of stimulator artifact), thought to reflect fast, oligosynaptic connections (Keller et al., 2011; 2014a, b). We quantified the presence and magnitude of a CCEP response at a given derivation in the following manner: first, we excluded recording sites that were within 10 mm (Euclidean distance) of the stimulating site; this and the fact that we used bipolar derivations ensured that the observed responses reflected local activation to focal stimulation of a distant site. Then, we excluded derivations that displayed no zero crossing within the first 500 msec (a sign that the stimulation artifact saturated the iEEG amplifier's filters). We then used the largest peak of the absolute CCEP t-score (polarity was irrelevant because we used bipolar derivations) during the 10–50 msec period as the index of connectivity between the stimulating and recording sites; if no peak was detected, the two sites were deemed not to be connected. We thus built square, weighted, directed adjacency matrices of directed connectivity, with nodes representing bipolar derivations and edges peak CCEP t-scores. Finally, we binarized these matrices by applying a threshold set at six times the standard deviation (SD) of t-scores during the baseline period (−200 to −25 msec). A similar criterion was developed by Keller and associates (2011), where it was found to provide the best combination of sensitivity and specificity for identifying the well-established projection between Broca's and Wernicke's areas. We also used more lenient (4 SDs) or more stringent (8 SDs) thresholds to test the robustness of our observations.

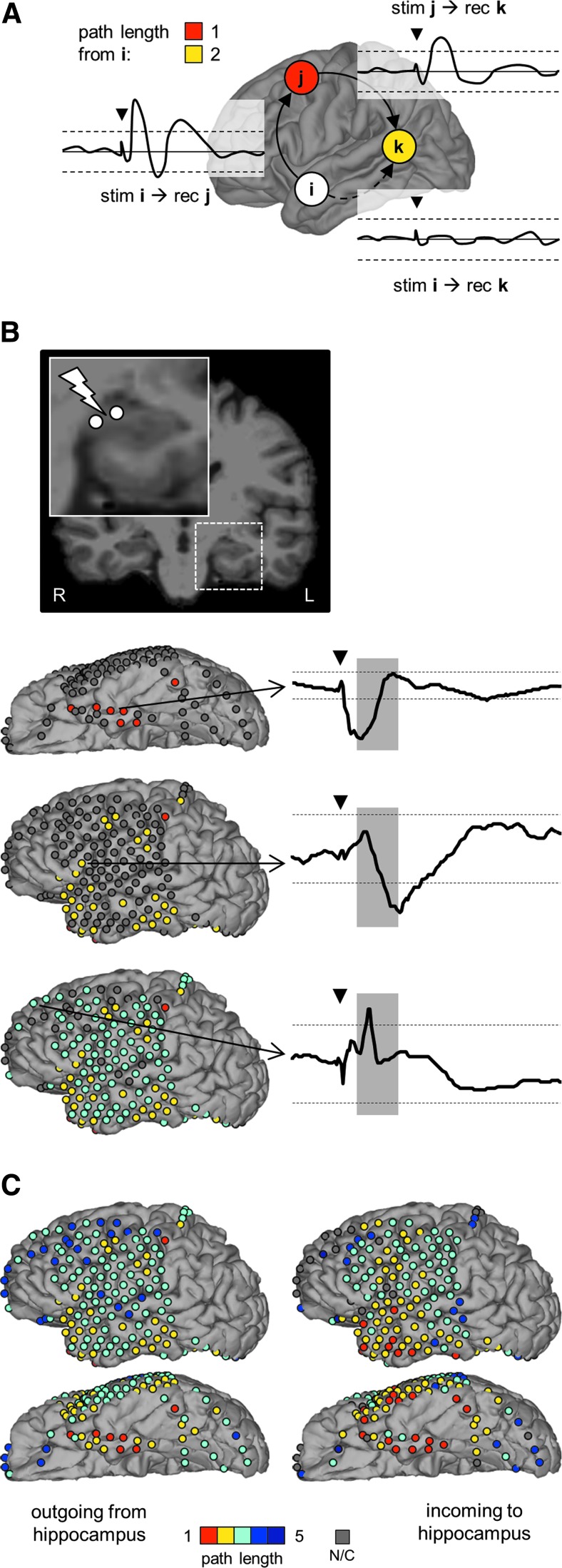

Because we were interested in assessing the directed connectivity between two brain regions of interest (hippocampus and amygdala) and the rest of the cerebral cortex, we used path length as the basic metric of connectivity. The shortest path length between two nodes is the minimal number of edges that one must travel along to go from one node to the other. Using the Brain Connectivity Toolbox (http://brain-connectivity-toolbox.net; Rubinov and Sporns, 2010), we computed the shortest incoming and outgoing path lengths between the hippocampal or amygdalar nodes and all the others. If a patient had more than one hippocampal or amygdalar node, we only retained the shortest path length at each node throughout the rest of the brain. The approach to measuring path length from CCEPs is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

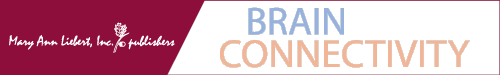

FIG. 1.

Probing hippocampal–cortical connectivity with CCEPs. (A) Postimplant CT coregistered with and superimposed onto preimplant magnetic resonance imaging (NB: the electrode artifacts on the CT are much larger than the electrodes themselves). Inset: pulses of electrical stimulation were delivered to the two distal-most electrodes, which lay in the hippocampus. (B) Hippocampal stimulation evoked a cluster of above-threshold responses in the inferior temporal lobe (white electrodes). Top inset: CCEP trace from an electrode pair with a significant, above-threshold response in the fusiform gyrus. Dashed horizontal lines depict the significance threshold (±6 standard deviations of the baseline t-score). The shaded area indicates the time interval (+10 to +50 msec) during which we assessed whether the CCEP had crossed the threshold. Bottom inset: CCEP trace from an electrode pair in the lateral occipital cortex that did not respond significantly to hippocampal stimulation. The black triangle shows the stimulation (0 msec), the dashed horizontal lines and shaded area have the same meaning as already mentioned. (C) Hippocampal response to stimulation of the inferior temporal gyrus [site highlighted in (B), top inset]. CT, computed tomography; CCEP, corticocortical evoked potential.

FIG. 2.

Measuring path length from CCEPs. (A). Schematic example. i, j, and k are cortical nodes. (B) Illustration of the approach with data from a representative patient. Starting from stimulation of the hippocampal node shown at the top, nodes with progressively larger path lengths are color coded on the cortical surface (left column; path length color codes refer to color scale in (C). Representative CCEP waveforms (plotted as in Fig. 1) are shown on the right: top, fusiform gyrus CCEP to hippocampal stimulation; middle waveform, inferior frontal gyrus CCEP to fusiform gyrus stimulation; bottom, superior frontal gyrus CCEP to inferior frontal gyrus stimulation. (C) The complete data from the representative patient are shown in (B). Path lengths from hippocampus to cortex (outgoing) and from cortex to hippocampus (incoming) are color coded on the patient's pial surface. NB: there are nodes that do not display any significant connection to the hippocampus. stim, stimulation; rec, recording; N/C, not connected.

Note that absolute path lengths as derived from CCEPs must be interpreted cautiously for two reasons. First, the thresholding imposed on CCEPs to binarize the connectivity matrices influences absolute path lengths, a more stringent threshold artificially lengthening all paths and vice versa. Second, because of the incomplete spatial sampling of the brain by iEEG electrodes, it is possible that cortical areas that seem to have very long path lengths would be found to have more direct connectivity if the entire brain were sampled. This is an inherent limitation of using CCEPs for studying the global connectivity of the brain (David et al., 2013). Here, to alleviate this limitation to some extent, we focus on the differences between incoming and outgoing path lengths between neocortical areas and the hippocampus or amygdala.

Statistical testing

Because apparently unconnected nodes (nodes with infinite path length) likely reflect incomplete sampling of the brain by our iEEG electrodes, rather than true absence of connecting pathways (i.e., any two brain regions are most likely connected to each other by some neuronal path, however complex), we discarded unconnected nodes in further analyses. We compared incoming versus outgoing path lengths across nodes using paired t-tests, with false discovery rate (FDR) correction when performing multiple comparisons (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). We compared the proportion of direct incoming versus outgoing connections (nodes with a path length of 1) using McNemar's test with continuity correction for the χ2 statistic. We assessed correlations using Pearson's linear correlation coefficient.

To compare path length across distinct cortical regions, we first ensured that both electrodes in the bipolar derivations (stimulating or recording) were in the same cortical region based on the FreeSurfer parcellation. Thus, we removed from the connectivity matrices those nodes where the electrode pair straddled a boundary between regions before computing the path lengths. We then performed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on incoming or outgoing path lengths across regions, followed by pair-wise Games–Howell post hoc tests between all region pairs. Only cortical regions with at least six observations were retained. The Games and Howell (1976) test can accommodate varying sample sizes and variances across groups, provided that there are at least six observations per group. These analyses should be considered exploratory because there was a large heterogeneity in the extent to which individual patients contributed nodes to each cortical region and because path lengths might not be independent across cortical regions in a given patient.

Results

We used CCEPs to study the directed connectivity between the hippocampus and amygdala and the cerebral cortex. We collected data from 21 patients implanted with iEEG electrodes (Table 1), encompassing 31 hippocampal (20 in the left hemisphere, 11 in the right) and 31 amygdalar nodes (20 left, 11 right), and 1851 nodes from other cortical regions (1471 left, 380 right). As electrodes were implanted based on clinical guidelines, there was greater sampling of the left hemisphere due to the need for language mapping. Patients implanted with stereo-EEG electrodes contributed fewer electrode pairs than those with subdural implants (average 20 [SD 14] vs. 108 [SD 47] per patient) as iEEG electrodes that lay in the white matter were excluded based on the FreeSurfer parcellation. Coverage was densest on the gyral crowns of the temporal lobe and the frontal convexity and sparser within the sulci, the parietal, and occipital lobes, the insula, and the medial hemispheric surface, reflecting both the usual localization of focal epilepsies and the ease of access of the respective regions to the intracranial electrodes.

Figure 1 illustrates how CCEPs were measured. In this example, stimulating an electrode pair in the hippocampus (Fig. 1A) induced significant responses in the inferior temporal cortex (Fig. 1B, top inset). We considered only early latency evoked responses (10–50 msec poststimulus) to focus on presumably direct oligosynaptic connections (Entz et al., 2014; Keller et al., 2014a, b). CCEPs were deemed significant if their amplitude, expressed as a t-score, was >6 times the SD of the prestimulus baseline (Keller et al., 2011). In Figure 1C, stimulation of the inferior temporal gyrus electrode pair, in turn, elicited a significant response from the hippocampus. Thus, the hippocampal and inferior temporal cortex nodes were reciprocally connected in this example. By contrast, the lateral occipital cortex did not respond directly to hippocampal stimulation (Fig. 1B, bottom inset).

The computation of path lengths from CCEPs is shown in Figure 2. In the schematic example (Fig. 2A), stimulation of node i evokes a significant response at node j (continuous arrow); therefore, the path length from i to j is 1. In contrast, stimulation of i does not evoke a significant response at node k (dashed arrow). Stimulating j, however, does evoke a significant response at k. To get from i to k, one, therefore, needs to travel along two connections (from i to j and from j to k), and the path length from i to k is 2. Figure 2B illustrates the approach with data from a representative patient. Starting from the top, all the nodes that directly responded to stimulation of the left hippocampus had a path length of 1 (color coded in red in Fig. 2B). Each of the nodes that responded to stimulation of those nodes, but had not responded to the initial hippocampal stimulation, had a path length of 2 with respect to the hippocampus (yellow). The analysis procedure is repeated to calculate the path length between any two sites as the smallest number of iterations required to include both sites. Figure 2C shows the complete data set for that representative patient in the outgoing (from hippocampus to cortex) and incoming (from cortex to hippocampus) directions.

Figure 3 depicts the directed connectivity of the cortex with the hippocampus and amygdala across all nodes of all patients. Practically the entire sampled cortical surface was connected with the hippocampus or amygdala, whether directly or indirectly. Figure 3 additionally suggests the following features of that connectivity:

• Path lengths were not identical across directions at individual nodes, incoming connections from cortex to hippocampus or amygdala expressing shorter path lengths than outgoing connections to the cortex (this is especially clear when comparing incoming and outgoing path lengths between cortex and hippocampus for the lateral view of the left hemisphere).

• Path lengths in a given direction differed across cerebral lobes and cortical areas, the temporal lobe having the most direct connectivity (shorter path lengths, color coded with warmer colors) and concentrating the majority of direct connections (path length of 1, color coded in red) in its medial and basal regions.

FIG. 3.

Path lengths for all cortical nodes across all patients. Path lengths are color coded over the Freesurfer average pial surface. Areas with lighter shades of gray correspond to gyri, those with darker shades correspond to sulci. From top to bottom: lateral, medial, and inferior views.

In what follows, we first characterize the directionality of connections between cortex and hippocampus or amygdala, and then focus on regional differences in connectivity.

Incoming connections from cortex to hippocampus or amygdala are more direct than outgoing connections to the cortex

To assess connectional directionality, we plotted in Figure 4A and B the difference between outgoing and incoming path lengths at individual cortical nodes so that nodes with shorter incoming path lengths (and, therefore, more direct incoming connections) are color coded in shades of red and, conversely, nodes with shorter outgoing path lengths (and, therefore, more direct outgoing connections) are in shades of blue. The distribution of path length differences is further represented as histograms (Fig. 4C, D). We found that path lengths were shorter in the incoming direction than in the outgoing direction across cortical nodes [paired t-tests, hippocampus: t(953) = 12.90, p < 0.0001; amygdala: t(656) = 3.97, p < 0.0001]. This indicates that incoming connections from the cortex to the hippocampus and amygdala were more direct than outgoing connections from those structures to the neocortex.

FIG. 4.

Comparing incoming and outgoing path lengths between cortex and hippocampus or amygdala. (A, B) Path length differences between cortex and hippocampus (A) or amygdala (B) at individual cortical nodes (outgoing–incoming) are color coded over the Freesurfer average pial surface. Positive values, coded in shades of red, indicate shorter incoming path lengths from cortex to hippocampus or amygdala than outgoing path lengths back to the cortex. (C, D) Histograms of the path length differences between cortex and hippocampus (C) or amygdala (D). Paired t-tests of outgoing versus incoming path lengths at individual cortical nodes revealed significantly shorter incoming path lengths for both the hippocampus and amygdala.

We also looked at direct connections (path length of 1, color coded in red in Fig. 3) between hippocampus or amygdala and the cerebral cortex. We found that there were more direct connections from cortex to hippocampus than from hippocampus to cortex [101 vs. 63 out of 954; McNemar's test: χ2(1) = 13.52, p = 0.0003]. Similarly, there were more direct connections from cortex to amygdala than from amygdala back to cortex [57 vs. 38 out of 657; χ2(1) = 6.00, p = 0.0143].

Because path length, the metric that we used to characterize connectivity, is dependent on thresholding, our findings might be influenced by the particular criterion that we used (that the response, expressed as a t-score, be larger than six times the SD of the baseline; see “Methods” section). We, therefore, repeated the previous analysis using a stricter threshold (8 SDs) and a more lenient one (4 SDs). A stricter threshold caused all path lengths to become longer, yet the distribution of path length differences at individual nodes continued to reveal shorter incoming than outgoing connections [paired t-tests, hippocampus: t(592) = 9.07, p < 0.0001; amygdala: t(426) = 5.25, p < 0.0001]. With a more lenient threshold, all path lengths became shorter. Incoming path lengths remained significantly shorter than outgoing path lengths in the case of the hippocampus [t(1306) = 2.84, p = 0.0045], but there was no difference between incoming and outgoing path lengths for the amygdala [t(950) = −0.95, p = 0.34]. This suggests that incoming connections from cortex to hippocampus and amygdala were indeed more direct than outgoing connections to the neocortex, and that this difference was more pronounced for the hippocampus than for the amygdala.

Another important potential confound is that, in a subset of patients, we stimulated depth electrodes (including hippocampal or amygdalar electrodes) at a lower amplitude than subdural electrodes (the vast majority of cortical electrodes) to reduce the occurrence of seizures when stimulating the seizure onset zone. Because the amplitude of CCEPs is, in part, proportional to the amplitude of the stimulus (Entz et al., 2014), we might have systematically biased part of our data set toward less ample responses to stimulation of the hippocampus or amygdala, which, in turn, would have caused artificially longer path lengths in the outgoing direction than in the incoming direction. To assess this, we repeated the previous analysis on two subsets of patients with subdural electrodes where the depth electrodes were stimulated at 10 or at 4–5 mA, respectively. We found that, in the case of the hippocampus, incoming path lengths at individual cortical nodes were shorter than outgoing path lengths regardless of stimulation amplitude [paired t-tests, 10 mA: t(378) = 11.64, p < 0.0001; 4–5 mA: t(553) = 7.27, p < 0.0001]. For the amygdala, incoming path lengths were also shorter than outgoing path lengths at 10 mA [t(224) = 3.58, p = 0.0004], but not statistically significant at 4–5 mA [t(404) = 1.70, p = 0.090]. This indicates that our observation that incoming path lengths from cortex to hippocampus or amygdala were shorter than outgoing path lengths to the cortex was not due to our reducing the stimulation amplitude at depth electrodes in a subset of patients.

We asked next whether path lengths between cortex and hippocampus or amygdala were shorter in the incoming direction than in the outgoing direction irrespective of the cerebral lobe involved. Incoming path lengths were significantly shorter than outgoing path lengths between the hippocampus and the temporal, frontal, and parietal lobes [Fig. 5A; paired t-tests with FDR correction, temporal lobe: t(277) = 7.34, pFDR < 0.0001; frontal lobe: t(172) = 3.07, pFDR = 0.0033; parietal lobe: t(86) = 5.90, pFDR < 0.0001; occipital lobe: t(17) = 0.94, pFDR = 0.36]. By contrast, incoming and outgoing path lengths between the amygdala and cortex did not differ significantly in any individual lobe, although there was a strong trend toward shorter incoming path lengths than outgoing path lengths in the temporal lobe and incoming path lengths tended to be shorter than outgoing path lengths across all lobes [Fig. 5B; temporal lobe: t(191) = 2.43, pFDR = 0.065; frontal lobe: t(139) = 0.31, pFDR = 0.76; parietal lobe: t(48) = 1.14, pFDR = 0.34; occipital lobe: t(6) = 1.55, pFDR = 0.34].

FIG. 5.

Incoming and outgoing path lengths between cortex and hippocampus or amygdala grouped by cerebral lobe. (A) Hippocampus, (B) Amygdala. Paired t-tests were used to compare outgoing versus incoming path lengths. FDR correction was applied to the p-values shown here (alpha = 0.05; see “Methods” section—“Statistical testing”). “*” denotes significant tests. Hippocampus, T: t(277) = 7.34, pFDR < 0.0001; F: t(172) = 3.07, pFDR = 0.0033; P: t(86) = 5.90, pFDR < 0.0001; O: t(17) = 0.94, pFDR = 0.36. Amygdala, T: t(191) = 2.43, pFDR = 0.065; F: t(139) = 0.31, pFDR = 0.76; P: t(48) = 1.14, pFDR = 0.34; O: t(6) = 1.55, pFDR = 0.34. SEM, standard error of the mean; FDR, false discovery rate; T, temporal lobe, including insula; F, frontal lobe; P, parietal lobe; O, occipital lobe.

The inferior temporal lobe has the shortest path lengths with the hippocampus compared with other cortical areas

We next explored the differences in connectivity between neocortex and hippocampus or amygdala across cortical areas. For that purpose, we grouped path lengths from individual nodes into cortical regions defined by each patient's gyral anatomy. Figure 6A shows the path lengths between cortex and hippocampus color coded on an average pial surface. Warmer colors indicate shorter path lengths, suggesting more direct connections, whereas colder colors indicate longer path lengths. We first confirmed that path lengths were not equal across cortical regions, in both directions [one-way ANOVA, incoming: F(21,588) = 4.83, p < 0.0001; outgoing: F(23,663) = 5.86, p < 0.0001]. We dissected this finding further using pairwise post hoc Games–Howell tests and found that incoming connections from the entorhinal cortex were significantly shorter than incoming connections from all occipital, parietal, and frontal regions as well as from the lateral temporal lobe. Incoming connections from the parahippocampal and fusiform gyri were also shorter than those from several cortical areas. Otherwise, incoming connections from the occipital, parietal, frontal, and lateral temporal regions were not significantly different in length from each other. In the outgoing direction, the shortest connections from the hippocampus also targeted the entorhinal cortex. Outgoing connections from the hippocampus to the posterior parietal cortex (superior parietal cortex and supramarginal gyrus) were noticeably longer than those toward the temporal lobe.

FIG. 6.

Regional cortical connectivity of the hippocampus and amygdala. (A) Incoming and outgoing path lengths between hippocampus and cortex grouped by cortical regions are color coded on the Freesurfer average pial surface. Areas with <6 observations are grayed. One-way ANOVA found significant differences in path lengths across areas in both directions [incoming: F(21,588) = 4.83, p < 0.0001; outgoing: F(23,663) = 5.86, p < 0.0001]. (B) Incoming and outgoing path lengths between amygdala and cortex are grouped by cortical regions. One-way ANOVA found significant differences in path lengths across areas in both directions [incoming: F(16,414) = 3.45, p < 0.0001; outgoing: F(17,441) = 3.59, p < 0.0001]. HIP, hippocampus; AMY, amygdala; ENT, entorhinal cortex; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; FUS, fusiform gyrus; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; MTG, middle temporal gyrus; STG, superior temporal gyrus; INS, insula; OFCl, orbitofrontal lateral cortex; IFGo, inferior frontal gyrus, pars orbitalis; IFGt, inferior frontal gyrus, pars triangularis; IFGp, inferior frontal gyrus, pars opercularis; MFGr, middle frontal gyrus, rostral part; MFGc, middle frontal gyrus, caudal part; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; PreC, precentral gyrus; PostC, postcentral gyrus; SPC, superior parietal cortex; IPC, inferior parietal cortex; SMG, supramarginal gyrus; LIN, lingual gyrus; LOC, lateral occipital cortex; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Figure 6B presents the same analysis for connections between the amygdala and cortical areas. Although path lengths between the amygdala and the cortex were not homogeneous across cortical areas [one-way ANOVA, incoming: F(16,414) = 3.45, p < 0.0001; outgoing: F(17,441) = 3.59, p < 0.0001], post hoc testing revealed few significant differences.

Path lengths when the hippocampus or amygdala is not involved in seizure onset

In most of the implanted hemispheres, the hippocampus or amygdala was part of the seizure onset zone as defined by visual inspection of the iEEG. This observation validates the clinical decision to implant these structures with depth electrodes in the first place. However, there could be differences in the connectivity pattern of the healthy and epileptic hippocampus or amygdala. We, therefore, assessed connectivity in the subset of hemispheres where the hippocampus and amygdala were not part of the seizure onset zone. We found the same overall connectivity pattern as in the entire data set: the shortest path lengths were in the temporal lobe, and there was a slight tendency for incoming path lengths to be shorter than outgoing path lengths for both the hippocampus and amygdala (although these differences did not reach statistical significance due to the small sample size). Although this limited subset of observations is by no means sufficient to conclude that there were no connectivity differences between the healthy and epileptic hippocampus or amygdala, it is at least reassuring in that it shows similar connectivity patterns in these two situations.

Discussion

In this study, we used CCEPs to probe the directed connectivity of the hippocampus and amygdala with the cerebral cortex. We found that the hippocampus and amygdala were connected with most of the cortical mantle, directly or indirectly. Uniquely, CCEPs assess the directionality of connections. Most connections between cortex and hippocampus or amygdala were asymmetric. Specifically, incoming path lengths from cortex to hippocampus were shorter than outgoing path lengths to the neocortex, and there were more direct connections from neocortex to hippocampus than from hippocampus to neocortex. We observed a similar, although slighter, asymmetry for amygdalar–cortical connections. This places the hippocampus, and to a lesser degree the amygdala, in the role of integrators of widespread cortical influence.

In our data, the entorhinal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus had the shortest path length with the hippocampus in both directions. This strong reciprocal hippocampal–entorhinal connectivity was previously described in human CCEP studies (Enatsu et al., 2015; Rutecki et al., 1989; Wilson et al., 1989). It likely reflects the position of the entorhinal, perirhinal, and parahippocampal cortices as gateways between the neocortex and the hippocampus proper, as revealed by anatomical studies in animal models (Amaral, 1993; Insausti et al., 1987; Lavenex and Amaral, 2000; Van Hoesen and Pandya, 1975; Van Hoesen et al., 1975) and MRI tractography in humans (Powell et al., 2004). Beyond this gateway, incoming path lengths to the hippocampus were remarkably similar across cortical areas, suggesting that activity from most of the neocortex has similar opportunities to reach the hippocampus. Resting fMRI (Greicius et al., 2004; Kahn et al., 2008; Vincent et al., 2006) and CCEP studies (Almashaikhi et al., 2014; Catenoix et al., 2005, 2011; Enatsu et al., 2015; Kubota et al., 2013; Lacruz et al., 2007) also reported distributed hippocampal–cortical connectivity. We found that path lengths from cortex to amygdala were also strikingly similar across cortical areas. Anatomical tracer studies (Amaral and Price, 1984; LeDoux, 2007; Sah et al., 2003), fMRI (Roy et al., 2009) and CCEP studies (Enatsu et al., 2015) confirm that the amygdala indeed entertains widespread connections with the neocortex.

The hippocampus and amygdala integrate the activity of many cortical areas into highly conceptual, context-invariant semantic representations of our environment. The widespread connectivity of the hippocampus and amygdala with the cerebral cortex revealed by our CCEPs, together with the fact that incoming connections from cortex to hippocampus or amygdala were more direct than their outgoing counterparts, is in keeping with this view of the hippocampus and amygdala as integrators of the activity of widely distributed cortical networks (Felleman and Van Essen, 1991; Mesulam, 1998; Quiroga, 2012).

Our results bear special relevance to noninvasive brain stimulation as a potential therapeutic intervention for neurological and psychiatric disorders (Fregni and Pascual-Leone, 2007). The hippocampus and amygdala have been implicated in many such diseases, and direct stimulation of the hippocampus, amygdala, or their dependencies using intracranial electrodes has been investigated to relieve symptoms in epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease, or post-traumatic stress disorder, among others (Fox et al., 2014). Although noninvasive brain stimulation is currently unable to reach directly deep-seated structures such as the hippocampus and amygdala, targeting cortical nodes strongly connected to these structures is an alternative noninvasive approach for brain stimulation (Fox et al., 2014). The pattern of cortical to hippocampal or amygdalar-directed connectivity that emerges from our data suggests that the inferior temporal cortex, temporal tip, and lower temporal lateral convexity would provide the most direct “gateway.” Interestingly, the high resting-state fMRI connectivity between the hippocampus and lateral parietal cortex has recently been used to target repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and improve performance in a memory task (Wang et al., 2014). Although connections from parietal cortex to hippocampus had long path lengths in our study, they were strongly directionally asymmetric, incoming connections from parietal cortex to hippocampus being markedly more direct than outgoing connections to parietal cortex. Thus, the net direction of information flow along cortical–hippocampal connections might be as important as their absolute strength for targeting neurostimulation. This hypothesis will need to be tested in future studies.

Several limitations to our study should be acknowledged. Because the medial temporal lobe was implicated in a large proportion of our subjects' epilepsy, a major concern is whether brain connectivity probed with CCEPs in our subjects approximates that of the healthy brain. Some studies do suggest that single-pulse electrical stimulation in epileptogenic cortex produces responses that differ from nonepileptogenic cortex (Enatsu et al., 2012a, b; Iwasaki et al., 2010; Valentin et al., 2002). However, in those studies, the most salient differences appeared later than 100 msec after the electrical stimulus (Valentin et al., 2002). This may be a lesser concern in our results due to the fact that CCEP analysis was restricted to earlier time points. Another consideration is that temporal lobe epilepsy may be accompanied by changes in cerebral morphology (Bonilha et al., 2010; Moran et al., 2001) and functional connectivity (Bettus et al., 2009; Pittau et al., 2012; Waites et al., 2006) that extend beyond the epileptic focus (Bernhardt et al., 2013). Owing to this concern, we believe that our admittedly small subset of patients with nonepileptic hippocampus or amygdala provides an important set of observations. In those patients, we found no major differences compared with the whole data set, although the small sample size limits statistical power. The agreement between our findings and prior anatomical and physiological studies also suggests that CCEP mapping in epileptic patients does index features of normal brain connectivity. The burgeoning indications for intracranial electrodes outside epilepsy (e.g., neuromodulation for intractable pain or investigative brain–computer interfaces) will provide future opportunities for CCEP mapping in nonepileptic brains.

The potential role of antiepileptic medication must also be mentioned. Indeed, antiepileptic drugs influence cortical excitability, and hence responses to electrical stimulation. A recent study found that two commonly used antiepileptic drugs with differing molecular mechanisms of action, lamotrigine and levetiracetam, exerted similar effects on transcranial magnetic stimulation-evoked cortical potentials (Premoli et al., 2017). Similarly, iEEG-derived measures of intrinsic cortical excitability were shown to vary mainly with the overall load of antiepileptic drugs in a given patient (Meisel et al., 2015). This suggests that the cumulative load of antiepileptic drugs, rather than the presence of any particular molecule versus another, would influence CCEPs. Here, all patients were under their usual antiepileptic medication when electrical stimulation was performed. Furthermore, the vast majority of our statistical comparisons were performed between pairs of electrodes in the same patient, thus balancing any potential role of specific antiepileptic medication or dosage on the CCEPs.

Another important consideration concerns spatial sampling, despite the rather large number of patients and electrodes included in our study. First of all, the major projection from the hippocampus through the Papez circuit (mammillary nucleus, anterior thalamic nucleus, and cingulate cortex) remained unexplored, because iEEG electrodes do not typically target these structures in the context of epilepsy. Nevertheless, the hippocampus also projects in a widespread manner to the neocortex through the entorhinal, parahippocampal, and perirhinal cortices, bypassing the Papez circuit; these projections might play an important role in the long-term storage of information by the neocortex (Lavenex and Amaral, 2000). Furthermore, we were unable to explore connections that were shown to exist, for instance, between the hippocampus and the medial parietal lobe or between the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex (Insausti et al., 1987; Kubota et al., 2013; Ongur and Price, 2000; Roy et al., 2009; Vincent et al., 2006). Data-sharing initiatives could allow the creation of large collaborative data sets with improved spatial sampling across larger number of patients.

Technical limitations must also be kept in mind. Action potentials evoked by electrical stimulation of the axon travel both orthodromically (away from the cell soma and toward synaptic terminals) and in the reverse direction. Antidromically propagated action potentials could theoretically travel forward again along axonal collaterals and evoke synaptic activity there, thus negating the directional selectivity of CCEPs. We cannot exclude that the stimulation parameters in our study evoked antidromic activity, but we believe that it played a relatively minor role in the results we observed. First, antidromic activation requires higher stimulation intensities than orthodromic activation (Ferster and Lindstrom, 1985; Rose and Metherate, 2001). Second, antidromic responses were only infrequently seen in cortical neurons upon electrical stimulation of the surface of the cat cerebral cortex at stimulation intensities sufficient to elicit clear evoked responses (Ezure et al., 1985). Third, antidromic action potentials appear less able than orthodromic action potentials to evoke synaptic activity, possibly because they fail to effectively propagate along axonal collaterals (Mulloney and Selverston, 1972). Accordingly, CCEPs are considered to reflect mostly orthodromic projections, with a minor antidromic contribution (Keller et al., 2014b; Matsumoto et al., 2007).

Another potential confound relates to the fact that the amplitude of CCEPs depends, like other evoked potentials, on the density and spatial organization of the pre- and postsynaptic elements (Mitzdorf, 1985; Tenke et al., 1993). Thus, the differing cellular and synaptic organization of the hippocampus, amygdala, and neocortex might influence the shape of CCEP curves to some extent and thus play a role in the connectivity differences observed here. Further studies will be necessary to resolve this issue by quantifying the neuronal responses to brain stimulation at a finer grain using microelectrode recordings of single-cell neuronal activity.

Conclusion

CCEPs are uniquely able to resolve the direction of neural connections. Using CCEPs, we showed that the directed connectivity from neocortex to hippocampus and amygdala is more direct than the reciprocal connectivity from these structures to the neocortex, placing the hippocampus and amygdala as integrators of widespread cortical influence. Despite a number of significant limitations (assessing connectivity in epileptic brains, incomplete spatial sampling of the neocortex dictated by the clinical situation), this study adds to our understanding of the functional organization of large-scale neural networks in the human brain.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients for their participation and Willie Walker, Jr., the physicians, and other professionals of the Neurosurgery and Neurology departments of North Shore University Hospital for their assistance. We thank Michael D. Fox for helpful comments on the article. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant P300P3_148388 to P.M.), KTIA (grant NAP_13-1-2013-0001 to L.E.), and the Page and Otto Marx Jr. Foundation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Almashaikhi T, Rheims S, Jung J, Ostrowsky-Coste K, Montavont A, Bellescize J, et al. 2014. Functional connectivity of insular efferences. Hum Brain Mapp 35:5279–5294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG. 1993. Emerging principles of intrinsic hippocampal organization. Curr Opin Neurobiol 3:225–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Price JL. 1984. Amygdalo-cortical projections in the monkey (Macaca fascicularis). J Comp Neurol 230:465–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B (Methodological) 57:289–300 [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt BC, Hong S, Bernasconi A, Bernasconi N. 2013. Imaging structural and functional brain networks in temporal lobe epilepsy. Front Hum Neurosci 7:624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettus G, Guedj E, Joyeux F, Confort-Gouny S, Soulier E, Laguitton V, et al. 2009. Decreased basal fMRI functional connectivity in epileptogenic networks and contralateral compensatory mechanisms. Hum Brain Mapp 30:1580–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha L, Edwards JC, Kinsman SL, Morgan PS, Fridriksson J, Rorden C, et al. 2010. Extrahippocampal gray matter loss and hippocampal deafferentation in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 51:519–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Di Martino A, Craddock RC, Mehta AD, Milham MP. 2013. Clinical applications of the functional connectome. Neuroimage 80:527–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catenoix H, Magnin M, Guenot M, Isnard J, Mauguiere F, Ryvlin P. 2005. Hippocampal-orbitofrontal connectivity in human: an electrical stimulation study. Clin Neurophysiol 116:1779–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catenoix H, Magnin M, Mauguiere F, Ryvlin P. 2011. Evoked potential study of hippocampal efferent projections in the human brain. Clin Neurophysiol 122:2488–2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner CR, Ellmore TM, DiSano MA, Pieters TA, Potter AW, Tandon N. 2011. Anatomic and electro-physiologic connectivity of the language system: a combined DTI-CCEP study. Comput Biol Med 41:1100–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David O, Guillemain I, Saillet S, Reyt S, Deransart C, Segebarth C, et al. 2008. Identifying neural drivers with functional MRI: an electrophysiological validation. PLoS Biol 6:2683–2697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David O, Job AS, De Palma L, Hoffmann D, Minotti L, Kahane P. 2013. Probabilistic functional tractography of the human cortex. Neuroimage 80:307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. 2006. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 31:968–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra AR, Chan AM, Quinn BT, Zepeda R, Keller CJ, Cormier J, et al. 2012. Individualized localization and cortical surface-based registration of intracranial electrodes. Neuroimage 59:3563–3570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enatsu R, Gonzalez-Martinez J, Bulacio J, Kubota Y, Mosher J, Burgess RC, et al. 2015. Connections of the limbic network: a corticocortical evoked potentials study. Cortex 62:20–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enatsu R, Jin K, Elwan S, Kubota Y, Piao Z, O'Connor T, et al. 2012a. Correlations between ictal propagation and response to electrical cortical stimulation: a cortico-cortical evoked potential study. Epilepsy Res 101:76–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enatsu R, Piao Z, O'Connor T, Horning K, Mosher J, Burgess R, et al. 2012b. Cortical excitability varies upon ictal onset patterns in neocortical epilepsy: a cortico-cortical evoked potential study. Clin Neurophysiol 123:252–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entz L, Toth E, Keller CJ, Bickel S, Groppe DM, Fabo D, et al. 2014. Evoked effective connectivity of the human neocortex. Hum Brain Mapp 35:5736–5753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezure K, Oguri M, Oshima T. 1985. Vertical spread of neuronal activity within the cat motor cortex investigated with epicortical stimulation and intracellular recording. Jpn J Physiol 35:193–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felleman DJ, Van Essen DC. 1991. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex 1:1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferster D, Lindstrom S. 1985. Augmenting responses evoked in area 17 of the cat by intracortical axon collaterals of cortico-geniculate cells. J Physiol 367:217–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B. 2012. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62:774–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Buckner RL, Liu H, Chakravarty MM, Lozano AM, Pascual-Leone A. 2014. Resting-state networks link invasive and noninvasive brain stimulation across diverse psychiatric and neurological diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E4367–E4375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. 2007. Technology insight: noninvasive brain stimulation in neurology-perspectives on the therapeutic potential of rTMS and tDCS. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 3:383–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston K, Moran R, Seth AK. 2013. Analysing connectivity with Granger causality and dynamic causal modelling. Curr Opin Neurobiol 23:172–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Games PA, Howell JF. 1976. Pairwise multiple comparison procedures with unequal N's and/or variances: a Monte Carlo study. J Educ Behav Stat 1:113–125 [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V. 2004. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer's disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:4637–4642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groppe DM, Bickel S, Dykstra AR, Wang X, Megevand P, Mercier MR, et al. 2017. iELVis: an open source MATLAB toolbox for localizing and visualizing human intracranial electrode data. J Neurosci Methods 281:40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groppe DM, Urbach TP, Kutas M. 2011. Mass univariate analysis of event-related brain potentials/fields I: a critical tutorial review. Psychophysiology 48:1711–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Amaral DG, Cowan WM. 1987. The entorhinal cortex of the monkey: II. Cortical afferents. J Comp Neurol 264:356–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki M, Enatsu R, Matsumoto R, Novak E, Thankappen B, Piao Z, et al. 2010. Accentuated cortico-cortical evoked potentials in neocortical epilepsy in areas of ictal onset. Epileptic Disord 12:292–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn I, Andrews-Hanna JR, Vincent JL, Snyder AZ, Buckner RL. 2008. Distinct cortical anatomy linked to subregions of the medial temporal lobe revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 100:129–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller CJ, Bickel S, Entz L, Ulbert I, Milham MP, Kelly C, et al. 2011. Intrinsic functional architecture predicts electrically evoked responses in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:10308–10313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller CJ, Honey CJ, Entz L, Bickel S, Groppe DM, Toth E, et al. 2014a. Corticocortical evoked potentials reveal projectors and integrators in human brain networks. J Neurosci 34:9152–9163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller CJ, Honey CJ, Megevand P, Entz L, Ulbert I, Mehta AD. 2014b. Mapping human brain networks with cortico-cortical evoked potentials. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369:pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Enatsu R, Gonzalez-Martinez J, Bulacio J, Mosher J, Burgess RC, et al. 2013. In vivo human hippocampal cingulate connectivity: a corticocortical evoked potentials (CCEPs) study. Clin Neurophysiol 124:1547–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacruz ME, Garcia Seoane JJ, Valentin A, Selway R, Alarcon G. 2007. Frontal and temporal functional connections of the living human brain. Eur J Neurosci 26:1357–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavenex P, Amaral DG. 2000. Hippocampal-neocortical interaction: a hierarchy of associativity. Hippocampus 10:420–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. 2007. The amygdala. Curr Biol 17:R868–R874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markov NT, Ercsey-Ravasz MM, Ribeiro Gomes AR, Lamy C, Magrou L, Vezoli J, et al. 2014. A weighted and directed interareal connectivity matrix for macaque cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex 24:17–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markov NT, Ercsey-Ravasz M, Van Essen DC, Knoblauch K, Toroczkai Z, Kennedy H. 2013. Cortical high-density counterstream architectures. Science 342:1238406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto R, Nair DR, LaPresto E, Bingaman W, Shibasaki H, Luders HO. 2007. Functional connectivity in human cortical motor system: a cortico-cortical evoked potential study. Brain 130(Pt 1):181–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel C, Schulze-Bonhage A, Freestone D, Cook MJ, Achermann P, Plenz D. 2015. Intrinsic excitability measures track antiepileptic drug action and uncover increasing/decreasing excitability over the wake/sleep cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:14694–14699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM. 1998. From sensation to cognition. Brain 121(Pt 6):1013–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitzdorf U. 1985. Current source-density method and application in cat cerebral cortex: investigation of evoked potentials and EEG phenomena. Physiol Rev 65:37–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran NF, Lemieux L, Kitchen ND, Fish DR, Shorvon SD. 2001. Extrahippocampal temporal lobe atrophy in temporal lobe epilepsy and mesial temporal sclerosis. Brain 124(Pt 1):167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulloney B, Selverston A. 1972. Antidromic action potentials fail to demonstrate known interactions between neurons. Science 177:69–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongur D, Price JL. 2000. The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, monkeys and humans. Cereb Cortex 10:206–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittau F, Grova C, Moeller F, Dubeau F, Gotman J. 2012. Patterns of altered functional connectivity in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 53:1013–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell HW, Guye M, Parker GJ, Symms MR, Boulby P, Koepp MJ, et al. 2004. Noninvasive in vivo demonstration of the connections of the human parahippocampal gyrus. Neuroimage 22:740–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premoli I, Biondi A, Carlesso S, Rivolta D, Richardson MP. 2017. Lamotrigine and levetiracetam exert a similar modulation of TMS-evoked EEG potentials. Epilepsia 58:42–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga RQ. 2012. Concept cells: the building blocks of declarative memory functions. Nat Rev Neurosci 13:587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose HJ, Metherate R. 2001. Thalamic stimulation largely elicits orthodromic, rather than antidromic, cortical activation in an auditory thalamocortical slice. Neuroscience 106:331–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, Shehzad Z, Margulies DS, Kelly AM, Uddin LQ, Gotimer K, et al. 2009. Functional connectivity of the human amygdala using resting state fMRI. Neuroimage 45:614–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinov M, Sporns O. 2010. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 52:1059–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutecki PA, Grossman RG, Armstrong D, Irish-Loewen S. 1989. Electrophysiological connections between the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in patients with complex partial seizures. J Neurosurg 70:667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Faber ES, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J. 2003. The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev 83:803–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon RV. 1992. A model of safe levels for electrical stimulation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 39:424–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Miller KL, Salimi-Khorshidi G, Webster M, Beckmann CF, Nichols TE, et al. 2011. Network modelling methods for FMRI. Neuroimage 54:875–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporns O. 2012. Discovering the Human Connectome. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- Tenke CE, Schroeder CE, Arezzo JC, Vaughan HG., Jr. 1993. Interpretation of high-resolution current source density profiles: a simulation of sublaminar contributions to the visual evoked potential. Exp Brain Res 94:183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin A, Anderson M, Alarcon G, Seoane JJ, Selway R, Binnie CD, et al. 2002. Responses to single pulse electrical stimulation identify epileptogenesis in the human brain in vivo. Brain 125(Pt 8):1709–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoesen G, Pandya DN. 1975. Some connections of the entorhinal (area 28) and perirhinal (area 35) cortices of the Rhesus monkey. I. Temporal lobe afferents. Brain Res 95:1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoesen G, Pandya DN, Butters N. 1975. Some connections of the entorhinal (area 28) and perirhinal (area 35) cortices of the rhesus monkey. II. Frontal lobe afferents. Brain Res 95:25–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, Snyder AZ, Fox MD, Shannon BJ, Andrews JR, Raichle ME, et al. 2006. Coherent spontaneous activity identifies a hippocampal-parietal memory network. J Neurophysiol 96:3517–3531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waites AB, Briellmann RS, Saling MM, Abbott DF, Jackson GD. 2006. Functional connectivity networks are disrupted in left temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol 59:335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JX, Rogers LM, Gross EZ, Ryals AJ, Dokucu ME, Brandstatt KL, et al. 2014. Targeted enhancement of cortical-hippocampal brain networks and associative memory. Science 345:1054–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JT, Ferguson MA, Nielsen JA, Anderson JS. 2013. BOLD Granger causality reflects vascular anatomy. PLoS One 8:e84279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CL, Isokawa M, Babb TL, Crandall PH. 1989. Functional connections in the human temporal lobe. I. Analysis of limbic system pathways using neuronal responses evoked by electrical stimulation. Exp Brain Res 82:279–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang AI, Wang X, Doyle WK, Halgren E, Carlson C, Belcher TL, et al. 2012. Localization of dense intracranial electrode arrays using magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 63:157–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]