Canada is one of only four Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations with a public health system where all citizens do not have publicly funded national medication insurance (the others are Israel, Mexico and the United States).1 As a result, provinces and territories have developed their own publicly funded medication insurance plans. This has led to a patchwork of medication insurance across Canada.2 Currently, the types of people who are covered and the coverage they have varies substantially across Canada. In this editorial we present the current situation using a patient example, identify the policy issues, and consider how physicians may improve the likelihood that their patients can afford their medications.

The Canadian patchwork

All residents of Canada are eligible for publicly funded medication; however, the coverage varies considerably and is confusing for patients. In addition to each province and territory having specific programs for those on social assistance, seniors and people younger than 65 years of age, there exists a variety of specialty plans that target specific diseases, such as cancer, palliative care or infectious diseases.3 Thus, all the provinces and territories offer something for all of their residents through a piecemeal approach.

Nevertheless, there are a variety of cost-sharing mechanisms used, which leads to large variations across the country. For example, people younger than 65 years who live in Alberta, Quebec and New Brunswick are charged premiums, and those who live in the remaining provinces are subject to high deductibles (an amount up to which a patient pays the full cost of the drug) ranging from 2%–35% of income across provinces and coinsurance (a set percentage of the amount per drug or per prescription that a patient pays).3 For those older than 65 years, some provinces do not have different plans than for those younger than 65 (British Columbia, Manitoba), others charge premiums (Quebec and Nova Scotia), and some use deductibles (British Columbia, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and some Saskatchewan seniors).3 In addition, several of the provinces use a sliding scale based on income, which offers more generous support from the government to those with lower incomes (British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick).3

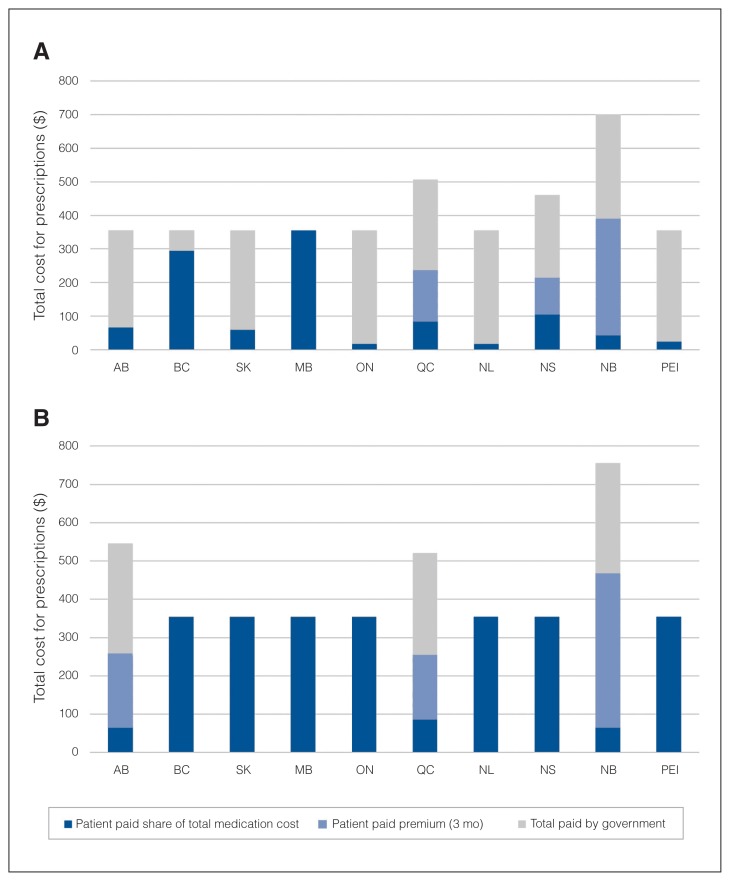

What do all these differences mean to a patient? Imagine a patient with a net household income of $55 600 (equivalent to Canada’s average net household income4) taking 20 mg/d of citalopram, 5 mg/d of aripiprazole and 7.5 mg/d of zopiclone. The total three-month prescription costs are approximately $354.5 However, for a patient older than 65 years, the out-of-pocket expenses, depending on the province of residence, vary from $18 to $390 (due to the premiums; Fig. 1A). For a patient younger than 65 years, the total out-of-pocket expense varies from $254 to $466, with the patient receiving no government support in seven provinces (Fig. 1B). The impact of this high spend translates into approximately 5.5% of Canadians reporting that they skip, stretch or simply do not take their medications.6 However, for those with mental health conditions the rates are much higher, with 21.4% reporting that they are unable to afford their medications.6

Fig. 1.

(A) What the government and a patient older than 65 years (annual net income of about $55 600) pay for a 3-month dispensation of 20 mg/d of citalopram, 5 mg/d of aripiprazole and 7.5 mg/d of zopiclone. (B) What the government and a patient younger than 65 years (annual net income of about $55 600) pay for a 3-month dispensation of 20 mg/d of citalopram, 5 mg/d of aripiprazole and 7.5 mg/d of zopiclone.

What can be done?

With the current context of varied patient costs across the country and a substantial number of Canadians unable to afford their medications, there are two main issues that must be addressed: financial barriers that patients face when filling their prescriptions and the high cost of medications. Others may add the lack of universality to the list of important policy issues but, as outlined previously, complete coverage already exists. The more important goal should be to reduce the number of Canadians who are unable to afford the medications to zero.

Targeting the high cost of drugs is one option. Pricing and reimbursement decision-making for medications involves three major agencies in Canada. After receiving a notice of compliance, drugs are considered for public reimbursement by the Common Drug Review (CDR), run by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH). The CDR evaluates the clinical and cost-effectiveness, as well as patient input.7 If this process results in a positive list decision, the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA) begins a pricing negotiation. The pCPA consists of all provincial, territorial and federal drug plans. The objectives are 1) to increase access to drug treatment options, 2) to achieve lower drug costs and consistent pricing across Canada, and 3) to improve consistency of coverage criteria across Canada.8 The primary mechanism to achieve these goals is through joint negotiation; the provinces and territories are able to form a larger market share and drive down prices. Although the negotiated prices remain confidential, the provinces and territories have estimated their savings at $490 million over the first five years of the pCPA.8 As the pCPA continues to develop its strategic and tactical negotiating positions, hopefully further price reductions will be realized, increasing the affordability of drugs for all Canadians.

Alongside this process, the price for which a medication can be sold is monitored by an independent body, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB), which ensures that Canadians are not paying excessive prices.9 Currently, the price is set by comparing the price of similar medications with that of seven other countries (France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States). With the United States — the highest-priced pharmaceutical market in the world — in our basket, what is considered an “excessive price” remains high relative to prices in other countries. Proposed changes to the PMPRB include changes to the basket of countries to exclude the United States and Switzerland.9 Changing them out for seven other OECD countries with lower prices is expected to drive down the median cross-country price of drugs. If successfully adopted, this change, combined with new reporting requirements, will hopefully result in substantial price reductions for medications.

Another approach to increase purchasing power and thus drive down costs is the adoption of a national pharmacare plan. National pharmacare is defined as public coverage of medically necessary prescription drugs on universal terms and conditions across Canada, including limited patient co-payments and a basic list of medications available for all Canadians.10 Recent research has found that national pharmacare could reduce private insurers’ costs by $8.2 billion and increase the costs to public plans by $1 billion, achieving a total medication spend reduction of $7.3 billion.10 These savings would be achieved by again consolidating the market share with national negotiations. This analysis also assumes that a larger market would be able to promote better medication selection and that coinsurance would be maintained. However, the progress that the provinces have made through the pCPA negotiations are not taken into account, and due to the confidential nature of pricing agreements, the complexity of how rebates are captured and the exemptions to the Freedom and Privacy Information Act for drug pricing, the actual total net drug budget is impossible to estimate for someone outside of the government. Finally, if coinsurance is maintained, the impact on the financial barriers experienced by patients when they access their medications is unlikely to change.

It is important to consider the push for national pharmacare within the current context. Within the recent budget announcement, there was the establishment of yet another committee to study the possibility of national pharmacare and what the options might be.11 Importantly, there was no funding attached for implementation, and the federal minister very quickly tempered expectations with statements clarifying that Canadians should not expect complete first-dollar government-funded coverage. In the absence of a signal of strong federal leadership, pan-provincial collaborations are more likely to advance policy while we wait for national pharmacare.

What can physicians do immediately?

There have been strides, and efforts continue, to rethink medication coverage in Canada. Notably, the provinces have made important advancements together, in the absence of federal leadership, to tackle the high price of drugs. However, there remain large variations in patient costs across the country, and 5% of Canadians — 21% of those with mental health issues — are still unable to afford their medications.6 To address this, as the bigger government machinery garners speed, physicians can support their patients individually.

By getting to know the publicly funded options within their own province, physicians can encourage patients to access all the support available to them. In many cases, this includes publicly funded drug insurance without premiums. In addition, physicians can prescribe least-cost alternatives when appropriate. For example, in the patient case described earlier, if the patient was prescribed brand drugs (Celexa and Imovane) rather than the off-patent generics citalopram and zopiclone, the total cost would have been about $200 higher for the 3-month prescription, bringing the total to about $554, which is a substantial cost to the patient as they would pay the entire cost difference. In addition, physicians could complete medication reconciliations on a regular basis. Stopping unnecessary and ineffective medications can help reduce the out-of-pocket burden for patients.

Finally, we must stop accepting the status quo. Stepping back, our current system could be seen as a tax on the sick. Every time someone tries to get a medication, they must pay a percentage of the total cost to receive that medication. This approach, used in nearly all OECD countries, has become the norm.1 We do not accept that for any other essential health care service, such as physician visits or hospitalizations. Why would we do so for another component of essential health care: drugs? We must continue to develop approaches and strategies that could be offered within the current budget yet do not result in Canadians being unable to afford their medications.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this editorial are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Canadian Medical Association or its subsidiaries, the journal’s editorial board or the Canadian College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Barnieh L, Clement F, Harris A, et al. A systematic review of cost-sharing strategies used within publicly-funded drug plans in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daw JR, Morgan SG. Stitching the gaps in the Canadian public drug coverage patchwork? A review of provincial pharmacare policy changes from 2000 to 2010. Health Policy. 2012;104:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell DJ, Manns BJ, Soril L, et al. A comparison of Canadian public medication insurance plans and the impact on out-of-pocket costs. CMAJ Open. 2017;5:E808–13. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20170065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Statistics Canada. Canadian income survey, 2015. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2017. [accessed 2018 Apr 3]. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/170526/dq170526a-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Interactive Drug Benefit List. Edmonton (AB): Alberta Health; 2017. [accessed 2018 Mar 29]. Available: www.ab.bluecross.ca/dbl/idbl_main1.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Law MR, Cheng L, Kolhatkar A, et al. The consequences of patient charges for prescription drugs in Canada: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open. 2018;6:E63–70. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20180008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tierney M, Manns B Members of the Canadian Expert Drug Advisory Committee. Optimizing the use of prescription drugs in Canada through the Common Drug Review. CMAJ. 2008;178:432–5. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Quinn S, Mani A. Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance: context, best practices, trends and outlook. Ottawa (ON): PDCI Market Access; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drug pricing in Canada: Changes for the PMPRB with proposed amendments to the Patented Medicines Regulations. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; [accessed 2018 Mar. 15]. Available: www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/1/2017/2017-12-02/html/reg2-eng.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan SG, Law M, Daw J, et al. Estimated cost of universal public coverage of prescription drugs in Canada. CMAJ. 2015;187:491–7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.141564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budget 2018. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2018. [accessed 2018 Mar 15]. Equity and growth: a strong middle-class. Available: www.budget.gc.ca/2018/home-accueil-en.html. [Google Scholar]