Abstract

Cell culture is now available as a method for the production of influenza vaccines in addition to eggs. In accordance with currently accepted practice, viruses recommended as candidates for vaccine manufacture are isolated and propagated exclusively in hens' eggs prior to distribution to manufacturers. Candidate vaccine viruses isolated in cell culture are not available to support vaccine manufacturing in mammalian cell bioreactors so egg-derived viruses have to be used. Recently influenza A (H3N2) viruses have been difficult to isolate directly in eggs. As mitigation against this difficulty, and the possibility of no suitable egg-isolated candidate viruses being available, it is proposed to consider using mammalian cell lines for primary isolation of influenza viruses as candidates for vaccine production in egg and cell platforms.

To investigate this possibility, we tested the antigenic stability of viruses isolated and propagated in cell lines qualified for influenza vaccine manufacture and subsequently investigated antigen yields of such viruses in these cell lines at pilot-scale. Twenty influenza A and B-positive, original clinical specimens were inoculated in three MDCK cell lines. The antigenicity of recovered viruses was tested by hemagglutination inhibition using ferret sera against contemporary vaccine viruses and the amino acid sequences of the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase were determined. MDCK cell lines proved to be highly sensitive for virus isolation. Compared to the virus sequenced from the original specimen, viruses passaged three times in the MDCK lines showed up to 2 amino acid changes in the hemagglutinin. Antigenic stability was also established by hemagglutination inhibition titers comparable to those of the corresponding reference virus. Viruses isolated in any of the three MDCK lines grew reasonably well but variably in three MDCK cells and in VERO cells at pilot-scale. These results indicate that influenza viruses isolated in vaccine certified cell lines may well qualify for use in vaccine production.

Keywords: Influenza vaccines, Vaccine-certified cell lines, MDCK, VERO, Virus isolation, Virus purification, Antigenic stability, Genetic stability

1. Introduction

Vaccination is the cornerstone of the global public health strategy to mitigate an eventual influenza pandemic. Rapid production of vaccine to immunize billions of people in a short period of time requires development of alternative manufacturing platforms, such as large-scale animal cell culture bioreactors. In combination with other methods, cell-based manufacturing would augment vaccine manufacturing capacity to respond to a pandemic [1]. MDCK and VERO cell culture–derived influenza vaccines have received regulatory approval in some countries [2,3]. Influenza vaccines produced in cell cultures have relied on candidate vaccine viruses developed by the WHO GISRS laboratories for vaccine production in embryonated eggs [4]. Although these viruses are ideal for the traditional method of vaccine production in eggs, the growth can be suboptimal for production of vaccines in cell cultures [4]. A sustainable supply of circulating influenza viruses isolated in cell cultures that meet regulatory requirements would be required to support cell-based vaccine manufacturing. Critical information on the comparative performance of several regulatory requirement-compliant cell lines for isolation of influenza viruses from clinical species for subsequent use as candidate vaccine viruses is not available. In addition, it would be important to determine whether isolation of viruses in a given cell line could have a detrimental impact on antigen yields in different cell lines used by other manufacturers; i.e. Does virus isolation in suspension select for variant viruses with lower replication efficiently in adherent cells? This information would support the selection of a certified cell line to be used in the WHO Collaborating Centers for isolation of candidate viruses for vaccine manufacturing. Given the variability of isolation rates in embryonated eggs [4–6], isolation of influenza viruses in cell culture would greatly increase the number of vaccine candidate viruses and, in some circumstances, accelerate development of viruses for vaccine manufacturing in both cell-based and egg-based platforms.

The continuous evolution of influenza viruses is monitored by the WHO Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) [5,7–9]. One of the main roles of this network is to provide candidate viruses for the production of influenza vaccines. Vaccine viruses recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) are mainly isolated and propagated in embryonated hens' eggs or chicken embryonic kidney cells prior to distribution to vaccine manufacturers. However, a number of contemporary influenza viruses replicate poorly in eggs [4,6], and therefore many laboratories replaced this substrate with partially characterized mammalian cells for the primary isolation of influenza viruses from clinical specimens, although these isolates cannot then be used for vaccine production as the cells are not usually qualified for manufacturing purposes. In contrast, viruses isolated in vaccine-qualified cell lines would be suitable as candidate vaccine viruses as long as they are in compliance with all other regulatory requirements [6,10,11]. Evaluation, development, and validation of this alternative strategy should therefore be undertaken [12–14]. Manufacturers currently use Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells [2,15,16] and African Green Monkey Kidney (VERO) cells [17–20] to manufacture licensed influenza vaccines. In addition, CAP human amniocyte [21] and PER.C6 cells derived from a human retinoblastoma [22,23] are being considered as growth substrate for influenza viruses.

To qualify for vaccine production, virus isolates must meet a number of requirements. First, they must be exclusively propagated in cell lines that meet regulatory requirements for vaccine production [10,11]. Second, virus preparations must be free of adventitious agents [10]. Third, antigenic and genetic properties of the viruses must remain stable over several passages and viruses should grow to accepted high titers in both eggs and the cell lines certified for vaccine production [10,24,25]. Cell lines to be used for the primary isolation of influenza viruses from clinical specimens and vaccine production must be sensitive to both, influenza A and B viruses.

MDCK cells have the potential to meet regulatory standards for vaccine production, and they support the growth of influenza viruses from original clinical specimens and after passage. It is known that influenza viruses isolated and propagated in mammalian cells often remain genetically and antigenically closely related to the virus present in clinical specimens [26–28]. Isolation in embryonated hens' eggs and also in cells can lead to amino acid changes in the hemagglutinin, which can occasionally alter antigenicity rendering the isolates unsuitable as candidate vaccine viruses [29–31]. Cell culture isolates may thus increase the number of viruses available for vaccine virus selection and regulatory authorities are willing consider such viruses for the production of influenza vaccines [24,32].

In the present study we evaluated the performance of vaccine manufacturing cell lines [12,14,15,17,33,34] for primary virus isolation from clinical specimens and analyzed the antigenic stability and antigen yields of resulting isolates in pilot-scale manufacturing processes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental design

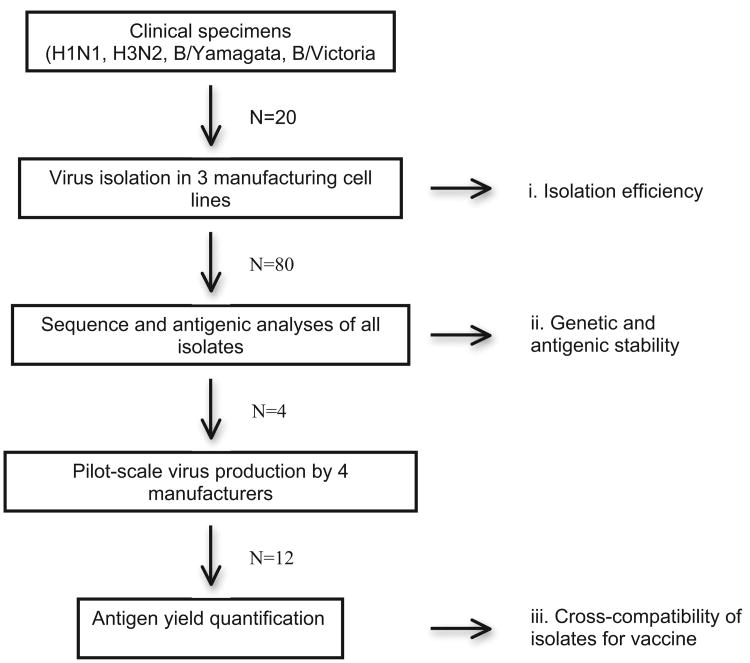

This study was designed to serve two purposes. Cell lines used by vaccine manufacturers were evaluated for their permissiveness to isolate influenza viruses from clinical specimens. Genetic and antigenic stability, as well as the growth-characteristics of the isolates, were monitored in the homologous cell line and in those used by other manufacturers. Fig. 1 shows the 4 main experimental steps and the 3 critical performance parameters of this study.

Fig. 1.

Goals of the study. The sensitivity of vaccine-certified cell lines for the primary isolation of influenza viruses from clinical specimens; the antigenic and genetic stability of influenza viruses propagated in vaccine-certified cell lines; virus yield in pilot scale production platforms; antigen yield in pilot scale production platforms.

2.2. Clinical specimens

Twenty influenza virus-positive respiratory samples from patients with influenza-like illness were included. These samples were collected in the USA or in Finland during the 2007–2008 and 2008–2009 influenza seasons. Four groups of five specimens were selected to represent each of the seasonal influenza subtypes: A(H1N1) viruses, A(H3N2) viruses, influenza B viruses representing the Yamagata lineage and the Victoria lineage. Each original specimen was divided into 10 aliquots and stored at −80°C until used for further experiments.

2.3. Cell lines, culture conditions, virus isolation, and pilot-scale production

Three different Madin-Darby canine kidney cell lines (MDCK-1 [14,15]; MDCK-2[12,14,33]; MDCK-3[33]) and one African green monkey cell line (VERO [17]) were used in the experiments. The MDCK-1 and MDCK-2 as well as the VERO cell lines were anchorage-dependent; whereas the MDCK-3 line was cultivated in suspension. The three MDCK cell lines were used for primary isolation of influenza viruses from clinical specimens and for pilot-scale virus production. The VERO cell line was used for small-scale production experiments, one representative isolate from each of the four virus groups (H1N1, H3N2, B-Victoria, B-Yamagata) was used. For production, MDCK-1 was grown on micro-carriers in serum free medium to which a protease was added to facilitate virus replication. Virus was harvested when cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed in all cells. MDCK-2 were grown in T-225 flasks in a serum-free medium, virus growth was monitored by microscopic observation for CPE and by hemadsorption assay (HA). MDCK-3 grew as a single-cell suspension in disposable shake flasks in a serum-free medium supplemented with recombinant bovine trypsin. VERO cells were grown on micro carriers in serum-free medium supplemented with trypsin. Virus from small-scale production was harvested, clarified, stabilized by addition of 5% glycerol using a standard protocol, stored at ≦−60°C, and shipped to the CDC for viral antigen content determination.

2.4. Nucleotide sequence analysis from clinical specimens and virus isolates

The full-length open reading frame of the hemagglutinin (HA) and the neuraminidase (NA) genes were sequenced following PCR-amplification as described [35]. Sequences were submitted to GenBank (accession numbers in supplementary Table S1).

2.5. Antigenic characterization by hemagglutination-inhibition assay

Antigenic characterization of the isolates was achieved by hemagglutination inhibition assay (HI) according to a standardized protocol, using ferret antisera raised against a panel of cell-grown reference viruses and either turkey or guinea pig red blood cells[36].

2.6. Viral antigen yield assessment

Viruses originally isolated in the 3 MDCK cell lines were then propagated on a small-scale production platform by four vaccine producers in their respective certified cell lines. Virus yield was monitored by methods representative of those routinely used by these producers for assessing virus production, i.e., hemagglutination; infectivity titration with a Tissue Culture Infectious Dose 50% endpoint (TCID50); infectivity titration by fluorescent focus forming unit (FFU); infectivity titration by fluorescent infection unit (FIU), respectively. A 22.5 mL volume of pooled supernatants from small-scale production batches was layered on to 9 mL of 30% (w/w) sucrose on top of a cushion of 4.5 mL 55% (w/w) sucrose and centrifuged at 90,000 × g for 14h at 4°C. Fractions were collected from the top of the sucrose gradient and those with the highest HA titers and protein concentration were pooled. The virus was pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2h at 4°C. Total protein content in resuspended viral pellets was determined by the BCA method [37] and expressed as total viral protein (mg/100 mL) for each cell harvest.

3. Results

3.1. Virus isolation efficiency

For primary virus isolation, an aliquot of the 20 clinical samples was inoculated into the three MDCK cell lines and embryonated hens' eggs. In MDCK-2 and MDCK-3 cells all viruses grew after one blind passage following primary inoculation (Table 1). All five influenza A(H1N1) and B Victoria-lineage viruses but only 60% of the B Yamagata-lineage viruses grew at the second passage in MDCK-1 cells, whereas 60% of influenza A(H3N2) viruses grew on the third passage. For comparison, isolation efficiency in eggs was 60% for influenza A(H1N1) and influenza B Victoria-lineage, 40% for influenza A (H3N2), and 20% for influenza B Yamagata-lineage at passage levels E3, E4, E3, and E3, respectively. The characteristics of viruses isolated in embryonated hens' eggs will be presented elsewhere [38]. Overall, both anchorage dependent and suspension MDCK cells were more sensitive than eggs by at least an order of magnitude for primary isolation of influenza A and B viruses.

Table 1.

Isolation of seasonal influenza viruses in MDCK cell lines used in vaccine manufacturing.

| Cell line | Total number of isolates recovered | Influenza A(H1N1) | Influenza A(H3N2) | Influenza B Victoria-like | Influenza B Yamagata-like | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| P1a | P2b | P1 | P2 | P1 | P2 | P1 | P2 | ||

| MDCK-1 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1c | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| MDCK-2 | 20 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| MDCK-3 | 20 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

Isolates recovered upon primary inoculation.

Isolates recovered upon first blind passage.

Two additional influenza A(H3N2) isolates were obtained upon second blind passage.

3.2. Genetic stability of viruses during isolation and pilot-scale propagation

To analyze the genetic stability of the HA and NA genes after sequential passages in each of the three MDCK lines their sequences were compared to those amplified directly from the clinical specimens. The number of amino acid changes observed in the hemagglutinin of the viruses recovered after passage in the respective cell lines are shown in Table 2. Compared to the virus present in the original specimen, viruses passaged three times in the MDCK lines showed on average between 0 and 2.2 amino acid changes in the hemagglutinin, resembling changes noted by isolation in eggs [26,28,39–44]. The number of amino acid changes in the NA were similar to those of observed in the HA (data not shown).

Table 2.

Cumulative amino acid mutations observed in the HA of viruses analyzed after 3 passages in the MDCK cell linesa.

| Cell line | A(H1N1) | A(H3N2) | B-Victoria | B-Yamagata |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDCK-1 | 11 (1–4)b | 6 (0–2) | 9 (1–4) | 5 (0–3) |

| MDCK-2 | 8 (0–3) | 4 (0–3) | 7 (0–3) | 4 (2) |

| MDCK-3 | 2 (0–1) | 11 (2–3) | 5 (0–3) | 0 (0) |

| Total number of mutations | 15 | 15 | 15 | 9 |

| Average mutations/virus | 0.4–2.2 | 1–2.2 | 1–1.8 | 0–2 |

Amino acid changes relative to the sequence from original clinical specimen.

Range of amino acid substitutions identified per individual viruses.

3.3. Antigenic stability of viruses propagated in different cell lines

After three passages in each of the three MDCK cell lines, antigenic characteristics of the viruses were determined by HI test. HI titers of tested viruses were compared with those obtained with the reference virus, and the number of viruses with significant reduction of HI titers relative to homologous titers of the reference viruses are shown in Table 3. HI titers obtained from the different viruses with a given antiserum were within ≤4-fold of the titer its homologous antigen, indicating that a majority of viruses propagated in any of the three cell lines were antigenically similar to the reference viruses. However, ≥4-fold differences in HI titers were observed among several viruses isolated from MDCK cell lines. Interestingly, most of the ≥4-fold HI titer differences were observed among the H3N2 viruses followed by H1N1 viruses. The majority of influenza B viruses isolated from the three MDCK cell lines showed HI titer differences <4-fold relative to the homologous virus titers.

Table 3.

Antigenic characterization of influenza viruses propagated in three different MDCK cell lines.

| Cell line | HI titer reductionb | Ferret antiserum toa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Influenza A(H1N1) | Influenza A(H3N2) | Influenza B Yamagata lineage | Influenza B Victoria lineage | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Brisbane/59/2007 | Hong Kong/1870/2008 | Brisbane/10/2007 | Perth/16/2009 | Florida/4/2006 | Bangladesh/3333/2007 | Brisbane/60/2008 | Texas/26/2008 | ||

| MDCK-1 | 0-fold | 1(5)c | 2(3) | 2(3) | 3(3) | 3(3) | |||

| 2-fold | 4(5) | 1(5) | 2(5) | 1(5) | |||||

| 4-fold | 4(5) | 1(3) | 3(5) | 4(5) | |||||

| ≥8-fold | 1(3) | ||||||||

| MDCK-2 | 0-fold | 1(2) | 1(2) | 1(2) | 2(2) | 3(5) | |||

| 2-fold | 1(2) | 1(2) | 2(5) | 2(5) | |||||

| 4-fold | 1(2) | 3(5) | |||||||

| ≥8-fold | 1(2) | 1(2) | 2(2) | ||||||

| MDCK-3 | 0-fold | 4(5) | 3(5) | 3(5) | 3(5) | ||||

| 2-fold | 5(5) | 5(5) | 1(5) | 2(5) | 5(5) | 2(5) | |||

| 4-fold | 1(5) | ||||||||

| ≥8-fold | 1(5) | ||||||||

HI titers of tested viruses were compared with results obtained for the homologous reference viruses.

Number of viruses with x-fold reduction to homologous titers of the reference viruses listed.

Number of viruses tested in parenthesis.

3.4. Growth characteristics of viruses in small-scale production experiments

To determine growth-characteristics of viruses isolated in MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and MDCK-3 cells, representative viruses were further propagated on a small-scale scheme using the three MDCK cell lines and the VERO cell line at the production facilities of the holders of these cell lines. Growth characteristics were analyzed by methods routinely used by these manufacturers when monitoring virus replication. Results from these experiments suggested that influenza A and B viruses isolated in MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and MDCK-3 cell lines replicated to acceptable levels in comparison to levels routinely achieved by manufacturers in all four production cell lines but the virus titers could vary more than 10-fold (Table 4).

Table 4.

Virus yield of 4 representative viruses of the two influenza A subtypes and the two influenza B lineages.

| Cell line original virus isolation | Virus type, subtype | Virus identification | Cell line used for virus production | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| MDCK-1 | MDCK-2 | MDCK-3 | VERO-1 | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Infectivity HA (HPLCU/mL) Run 1 | Infectivity HA (HPLC U/mL) Run 2 | Infectivity titer Log10 FFUa /mL | HAb titer HAUc /100uL | Infectivity titer Log10 FIUd /mL | HA titer HAU/50 μL | Infectivity titer log10 TCID50e /mL | |||

| MDCK-1 | A(H1N1) | A/Texas/89/2009 | 13.3 | 12.5 | 5.6 | 1024 | 7.5 | 1024 | 7.8 |

| A(H3N2) | A/Finland/97/2009 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 512 | 7.5 | 128 | 7.2 | |

| B/Vicf | B/Texas/23/2009 | 19.7 | 16.3 | 5.7 | 1024 | 6.6 | 128 | 6.5 | |

| B/Yamag | B/Finland/214/2008 | 20.4 | 23.9 | 7.2 | 2048 | 8.0 | 256 | 7.3 | |

| MDCK-2 | A(H1N1) | A/Texas/89/2009 | 21.2 | No full CPE | 8.6 | 2048 | 7.8 | 256 | 7.5 |

| A(H3N2) | A/Finland/97/2009 | 11.9 | 15.1 | 7.3 | 256 | 6.8 | 512 | 7.5 | |

| B/Vic | B/Texas/23/2009 | 18.3 | 21.0 | 6.8 | 512 | 7.2 | 128 | 6.7 | |

| B/Yama | B/Finland/214/2008 | 26.4 | 22.8 | 6.9 | 2048 | 7.1 | 256 | 7.4 | |

| MDCK-3 | A(H1N1) | A/Texas/89/2009 | 18.8 | 11.5 | 8.8 | 2048 | 7.6 | 1024 | 8.4 |

| A(H3N2) | A/Finland/97/2009 | 17.0 | 11.4 | 7.7 | 256 | 7.6 | 64 | 7.4 | |

| B/Vic | B/Texas/23/2009 | 24.7 | 21.4 | 8.1 | 1024 | 7.0 | 32 | 4.8 | |

| B/Yama | B/Finland/214/2008 | 17.6 | 14.3 | 8.4 ± 0.04 | 2048 | 7.1 | 512 | 6.3 | |

FFU: fluorescent focus unit.

HA: hemagglutination.

HAU: hemagglutination units.

FIU: fluorescent infection focus unit.

TCID50: tissue culture infectious dose 50%.

Vic: Victoria-like.

Yama: Yamagata-like.

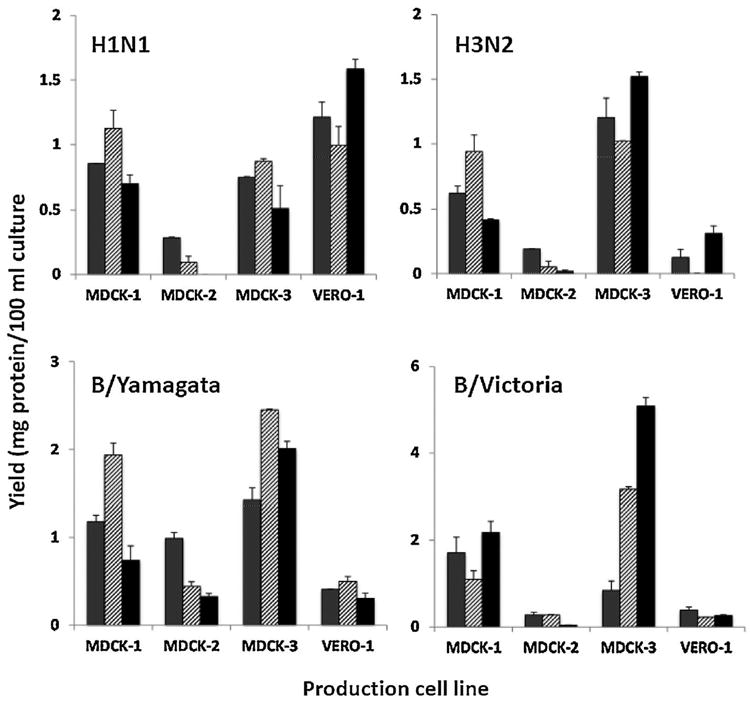

Virus protein yield from small scale production platforms was assessed after concentration and purification of virus from culture supernatant (Fig. 2). The purity of the sucrose gradient concentrated viruses from production cell lines MDCK-1 and MDCK-3 was further verified by SDS-PAGE analysis. Protein concentration analysis suggested that MDCK-1 and MDCK-3 cell lines produced higher antigen yields than the MDCK-2 and VERO cell line except for the superior yield of H1N1 antigen in the VERO cell line. These results indicate that different production cell lines may have variable yields of seasonal influenza viruses, mainly dependent on differences of the cell density required for optimal bioreactor conditions of the specific cell lines and therefore further adaptation or optimization in individual cell lines may be required for large-scale production, although these changes may alter the antigenic properties.

Fig. 2.

Virus protein yield in pilot scale production platforms. One representative A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) virus and one virus representing each of the two type B lineages isolated in each of the three cell lines (MDCK-1: gray stipple fill bar; MDCK-2: hatched fill bar; and MDCK-3: black fill bar) were propagated in four vaccine-certified cell lines (indicated in the horizontal axis). Virus was purified from 22.5 mL culture supernatant and the content of virus protein was determined. Values are means of two independent purifications, with the standard error shown as T bar extensions. The large differences among production cell lines are most likely the result of approximately 10-fold lower cell densities relative to optimal bioreactor conditions and do not necessarily diminish their acceptability for large-scale production of influenza vaccines.

4. Discussion

For the foreseeable future it is anticipated that the global supply of influenza vaccine will be manufactured predominantly in eggs. Vaccine production relies on a global network of public health, academic and industrial laboratories that work in concert to ensure the rapid update of vaccine composition when antigenic variants become dominant in the world [5]. The present study was designed to evaluate the performance characteristics of several cell lines which are already certified for or are currently being evaluated by national regulatory authorities to determine their suitability for human influenza vaccine manufacturing.

In general, MDCK cells appear to be the most permissive cell line for isolation and propagation of human and animal influenza viruses [45,46]. In the present study, the three MDCK cell lines used for primary isolation of influenza A and B viruses from clinical specimens proved to be highly sensitive. After one blind passage, all 20 isolates were detected in one of the two anchorage-dependent MDCK lines (MDCK-3) and in the suspension MDCK line. The anchorage-dependent MDCK-1 cells appeared to be slightly less sensitive, as two influenza A(H3N2) viruses and two influenza B viruses of the Yamagata lineage remained undetected. Recent influenza A(H3N2) may not grow or require one or more blind passages before the virus can be detected in culture. In this study eggs achieved a 45% isolation rate overall and 40% and 20% for A (H3N2) and B-Yamagata viruses, respectively, however during the last decade, the proportion of H3N2 viruses that has been recoverable in eggs has declined to <1% in some laboratories [4,6,31,47] and therefore, viruses isolated in cell culture may not grow in eggs.

Sequence analysis of the isolated viruses revealed up to 4 amino acid substitutions at 9 to 15 residues of the mature hemagglutinin in comparison to the sequence of the original virus isolated from the clinical sample. Importantly, several isolates from MDCK-2 and MDCK-3 were identical to the virus genomes in the original samples. It was noted that some of the observed mutations resulted in the loss or gain of potential glycosylation sites.

Comparing the cumulative number of mutations for viruses isolated in each of the cell lines revealed that viruses propagated in suspension-grown MDCK-3 cells showed the lowest number of amino acid substitutions, followed by MDCK-2 and MDCK-1. These differences were small and lacked statistical significance. This suggests that propagation of influenza viruses in these three MDCK lines does not lead to major changes in the amino acid sequence of the hemagglutinin.

The antigenic properties of viruses propagated in the three MDCK lines were determined by HI test using post-infection ferret antisera to reference or vaccine viruses used during the period when the clinical specimens were collected. The majority of viruses propagated in the three MDCK cell lines remained within ≦2-fold titer differences, suggesting that a high proportion of viruses propagated in different MDCK cells lines are antigenically similar to the reference viruses and would merit characterization by reciprocal HI testing. These results indicate that isolation and passage of influenza viruses in the commonly used MDCK cell lines can yield antigenically distinct viruses (HI titer differences of >4 fold) with low frequency.

As soon as vaccine manufacturers adopt the use of cell culture–isolated influenza viruses in vaccine production, one or more of the approved cell lines could be made available to WHO Collaborating Centers for the isolation of viruses from virus-positive samples received from National Influenza Centers. These qualified cell lines could provide an alternative to eggs in the event that isolation of a suitable virus for vaccine production has not been possible. Preliminary results from a follow-up studies show that H3N2 viruses with high infectivity harvested from MDCK cultures can be propagated in eggs. Results of egg based studies will be the subject of a separate report.

To estimate the potential performance of viruses isolated in various cell lines in cell-based vaccine manufacturing, one influenza A virus of each subtype and one influenza B virus of each lineage isolated in each of the three MDCK cell lines was grown in a small-scale production experiment using the three MDCK and the VERO cell lines at the corresponding vaccine manufacturing sites. Infectivity titers in cell culture supernatants were determined using different methods at each manufacturing plant, which makes quantitative comparisons unfeasible. However, antigen amounts as well as infectivity titers did not vary significantly in the different combinations of isolation and production cell lines. It is thus likely that viruses isolated in certified cell lines by WHO Collaborating Centers can be successfully propagated in any of the cell lines currently used by different vaccine producers.

Virus protein yields were determined after concentration and purification of virus from small-scale production. In these experiments the MDCK-2 cell line, in accordance to routine production procedures at this manufacturing plant, was used at one order of magnitude lower cell density than the other cell lines. As a consequence, protein yields from this cell line were approximately 2 to 10 times lower than those observed from the other cell lines. Protein yields from the other two MDCK cell lines did not differ significantly from each other. For the influenza A(H1N1) virus, the highest protein yields were obtained with the VERO cell line. However, with influenza A(H3N2) and influenza B viruses of both lineages, protein yields from the VERO cell line were 1.5 to 10-fold lower than those obtained with the MDCK-1 and MDCK-3 cell lines.

These experiments were designed as a proof of concept that influenza viruses isolated in cell cultures could be successfully used for production of influenza vaccines in certified mammalian cell lines selected by vaccine manufacturers. The MDCK cell lines proved to be sensitive for primary isolation of influenza A and B viruses. The viruses studied retained their genetic and antigenic properties well during propagation in the cell lines. Antigen and protein yields were comparable in all different combinations of cell lines for primary isolation and for production. The scarcity of positive clinical specimens with a sufficiently high virus titer and/or volume to allow for performance of all the experiments limited the total number of isolates tested. However, influenza viruses isolated in certified cell lines fulfilled all of the requirements needed for acceptable vaccine seed viruses. Although the A(H1N1) seasonal viruses used in the present study have been replaced by the A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses since the 2009 pandemic, these results may be applicable to the new lineage as well. The feasibility of influenza viruses isolated in certified cell lines for use in egg-based production platform is currently under evaluation and those results will be presented elsewhere.

Isolation of recent influenza A (H3N2) viruses is becoming increasingly difficult in eggs, which severely limits the number of available virus candidates that could be evaluated for vaccine production. Alternative strategies must therefore be designed, tested, and evaluated including the use of viruses isolated in approved cell lines for further propagation in both cell-based and egg-based influenza vaccine manufacturing. The promising results obtained in the present study may assist decision making by public health laboratories, regulatory agencies and industry regarding the generation of virus isolates for cell-based manufacturing of influenza vaccines

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Part of this work was funded by the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations (IFPMA). The authors acknowledge Dr. Theodore Tsai and Tony Piedra for providing clinical samples used in this study. The Melbourne WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza is supported by the Australian Government Department of Health. We thank Mr. Wei-Zhou Yeh at National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan for technical support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Several co-authors are employees of companies that produce influenza vaccines. The remaining co-authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.045.

References

- 1.Abelin A, Colegate T, Gardner S, Hehme N, Palache A. Lessons from pandemic influenza A(H1N1): the research-based vaccine industry's perspective. Vaccine. 2011;29:1135–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doroshenko A, Halperin SA. Trivalent MDCK cell culture–derived influenza vaccine Optaflu (Novartis Vaccines) Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:679–88. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett PN, Portsmouth D, Ehrlich HJ. Vero cell culture-derived pandemic influenza vaccines: preclinical and clinical development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2013;12:395–413. doi: 10.1586/erv.13.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minor PD, Engelhardt OG, Wood JM, Robertson JS, Blayer S, Colegate T, et al. Current challenges in implementing cell-derived influenza vaccines: implications for production and regulation, July 2007, NIBSC, Potters Bar, UK. Vaccine. 2009;27:2907–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ampofo WK, Baylor N, Cobey S, Cox NJ, Daves S, Edwards S, et al. Improving influenza vaccine virus selection: report of a WHO informal consultation held at WHO headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland, 14–16 June 2010. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:142–52. doi: 10.1111/irv.12081. e1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minor PD. Vaccines against seasonal and pandemic influenza and the implications of changes in substrates for virus production. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:560–5. doi: 10.1086/650171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stohr K, Bucher D, Colgate T, Wood J. Influenza virus surveillance, vaccine strain selection, and manufacture. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;865:147–62. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-621-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stohr K. Influenza—WHO cares. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:517. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell CA, Jones TC, Barr IG, Cox NJ, Garten RJ, Gregory V, et al. Influenza vaccine strain selection and recent studies on the global migration of seasonal influenza viruses. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl. 4):D31–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Services USDoHaH, editor. CBER/FDA. Guidance for industry on characterization and qualification of cell substrates and other biological materials used in the production of viral vaccines for infectious disease indications. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Services USDoHaH, editor. CBER/FDA. Guidance for industry on content and format of chemistry, manufacturing and controls information and establishment description information for a vaccine or related product. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Mani S, Schwartz R, Richman L, Tabor DE. Cloning and assessment of tumorigenicity and oncogenicity of a Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cell line for influenza vaccine production. Vaccine. 2010;28:1285–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palache AM, Brands R, van Scharrenburg GJ. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of influenza subunit vaccines produced in MDCK cells or fertilized chicken eggs. J Infect Dis. 1997;176(Suppl. 1):S20–3. doi: 10.1086/514169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Shi X, Schwartz R, Kemble G. Use of MDCK cells for production of live attenuated influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27:6460–3. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medema JK, Meijer J, Kersten AJ, Horton R. Safety assessment of Madin Darby canine kidney cells as vaccine substrate. Dev Biol (Basel) 2006;123:243–50. , discussion 65-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussain AI, Cordeiro M, Sevilla E, Liu J. Comparison of egg and high yielding MDCK cell-derived live attenuated influenza virus for commercial production of trivalent influenza vaccine: in vitro cell susceptibility and influenza virus replication kinetics in permissive and semi-permissive cells. Vaccine. 2010;28:3848–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kistner O, Barrett PN, Mundt W, Reiter M, Schober-Bendixen S, Dorner F. Development of a mammalian cell (Vero) derived candidate influenza virus vaccine. Vaccine. 1998;16:960–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett PN, Berezuk G, Fritsch S, Aichinger G, Hart MK, El-Amin W, et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of a Vero-cell-culture–derived trivalent influenza vaccine: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:751–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrlich HJ, Berezuk G, Fritsch S, Aichinger G, Singer J, Portsmouth D, et al. Clinical development of a Vero cell culture–derived seasonal influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2012;30:4377–86. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehrlich HJ, Singer J, Berezuk G, Fritsch S, Aichinger G, Hart MK, et al. A cell culture–derived influenza vaccine provides consistent protection against infection and reduces the duration and severity of disease in infected individuals. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:946–54. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer S, Charara N, Gerber A, Wolfel J, Schiedner G, Voedisch B, et al. Transient recombinant protein expression in a human amniocyte cell line: the CAP-T(R) cell system. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:2250–61. doi: 10.1002/bit.24514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pau MG, Ophorst C, Koldijk MH, Schouten G, Mehtali M, Uytdehaag F. The human cell line PER.C6 provides a new manufacturing system for the production of influenza vaccines. Vaccine. 2001;19:2716–21. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox RJ, Madhun AS, Hauge S, Sjursen H, Major D, Kuhne M, et al. A phase I clinical trial of a PER.C6 cell grown influenza H7 virus vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27:1889–97. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO. WHO technicalreport series no 927, annex 1. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2005. WHO guidelines on nonclinical evaluation of vaccines. [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Medicines Agency. Committee for medicinal products for human use VWPa BWPV, BWP) Guideline on influenza vaccines—quality module (draft for comment) BWP): Vaccine Working Party and Biologics Working Party (VWP. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz JM, Wang M, Webster RG. Direct sequencing of the HA gene of influenza (H3N2) virus in original clinical samples reveals sequence identity with mammalian cell-grown virus. J Virol. 1990;64:1808–11. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1808-1811.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer WJ, Wood JM, Major D, Robertson JS, Webster RG, Katz JM. Influence of host cell-mediated variation on the international surveillance of influenza A(H3N2) viruses. Virology. 1993;196:130–7. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson JS, Nicolson C, Major D, Robertson EW, Wood JM. The role of amniotic passage in the egg-adaptation of human influenza virus is revealed by haemagglutinin sequence analyses. J Gen Virol. 1993;74(Pt 10):2047–51. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-10-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson JS, Naeve CW, Webster RG, Bootman JS, Newman R, Schild GC. Alterations in the hemagglutinin associated with adaptation of influenza B virus to growth in eggs. Virology. 1985;143:166–74. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson JS, Bootman JS, Newman R, Oxford JS, Daniels RS, Webster RG, et al. Structural changes in the haemagglutinin which accompany egg adaptation of an influenza A(H1N1) virus. Virology. 1987;160:31–7. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kishida N, Fujisaki S, Yokoyama M, Sato H, Saito R, Ikematsu H, et al. Evaluation of influenza virus A/H3N2 and B vaccines on the basis of cross-reactivity of post vaccination human serum antibodies against influenza viruses A/H3N2 and B isolated in MDCK cells and embryonated hen eggs. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:897–908. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05726-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.EMA. Guideline on quality aspects on the isolation of candidate influenza vac-cine viruses in cell culture. London, UK: Committee for Human Medicinal Products (CHMP), European Medicines Agency; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gregersen JP. A quantitative risk assessment of exposure to adventitious agents in a cell culture–derived subunit influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2008;26:3332–40. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onions D, Egan W, Jarrett R, Novicki D, Gregersen JP. Validation of the safety of MDCK cells as a substrate for the production of a cell-derived influenza vaccine. Biologicals: J Int Assoc Biol Stand. 2010;38:544–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou B, Donnelly M, Scholes D, St George K, Hatta M, Kawaoka Y, et al. Single-reaction genomic amplification accelerates sequencing and vaccine production for classical and Swine origin human influenza a viruses. J Virol. 2009;83:10309–13. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01109-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WHO. Manual for the laboratory diagnosis and virological surveillance ofinfluenza. Geneva: WHO Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lane RD, Federman D, Flora JL, Beck BL. Computer-assisted determination of protein concentrations from dye-binding and bicinchoninic acid protein assays performed in microtiter plates. J Immunol Methods. 1986;92:261–70. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donis R, Blayer S, Colegate A, Ziegler T, Barr I, Bucher D, et al. Evaluation of qualified cell lines for isolation of influenza candidate vaccine viruses: from clinical specimen to high yield reassortant. ESWI, editor. 4th ESWI influenza conference; Malta: ESWI. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gambaryan AS, Robertson JS, Matrosovich MN. Effects of egg-adaptation on the receptor-binding properties of human influenza A and B viruses. Virology. 1999;258:232–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hardy CT, Young SA, Webster RG, Naeve CW, Owens RJ. Egg fluids and cells of the chorioallantoic membrane of embryonated chicken eggs can select different variants of influenza A(H3N2) viruses. Virology. 1995;211:302–6. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito T, Suzuki Y, Takada A, Kawamoto A, Otsuki K, Masuda H, et al. Differences in sialic acid-galactose linkages in the chicken egg amnion and allantois influence human influenza virus receptor specificity and variant selection. J Virol. 1997;71:3357–62. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3357-3362.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katz JM, Webster RG. Amino acid sequence identity between the HA1 of influenza A(H3N2) viruses grown in mammalian and primary chick kidney cells. J Gen Virol. 1992;73(Pt 5):1159–65. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-5-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers GN, Daniels RS, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Wang XF, Higa HH, et al. Host-mediated selection of influenza virus receptor variants, sialic acid-α2,6Gal-specific clones of A/duck/Ukraine/1/63 revert to sialic acid-α2,3Gal-specific wild type in ovo. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:7362–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Widjaja L, Ilyushina N, Webster RG, Webby RJ. Molecular changes associated with adaptation of human influenza A virus in embryonated chicken eggs. Virology. 2006;350:137–45. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reina J, Fernandez-Baca V, Blanco I, Munar M. Comparison of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK) with a green monkey continuous cell line (Vero) and human lung embryonated cells (MRC-5) in the isolation of influenza A virus from nasopharyngeal aspirates by shell vial culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1900–1. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1900-1901.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romanova J, Katinger D, Ferko B, Voglauer R, Mochalova L, Bovin N, et al. Distinct host range of influenza H3N2 virus isolates in Vero and MDCK cells is determined by cell specific glycosylation pattern. Virology. 2003;307:90–7. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu B, Zhou H, Ye D, Kemble G, Jin H. Improvement of influenza A/Fujian/411/02 (H3N2) virus growth in embryonated chicken eggs by balancing the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase activities, using reverse genetics. J Virol. 2005;79:6763–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6763-6771.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.