Abstract

Clostridium difficile infection in antibiotic-treated mice results in acute colitis characterized by severe intestinal histopathology, robust neutrophil influx, and increased expression of numerous inflammatory cytokines, including GM-CS F. We utilized a neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb) against GM-CS F in a murine model to study the role of GM-CS F during acute C. difficile colitis. Cefoperazone-treated mice were challenged with C. difficile (strain 630) spores. Expression of GM-CS F was significantly increased in animals challenged with C. difficile. Treatment with an anti-GM-CS F mAb did not alter C. difficile colonization levels, weight loss, or expression of IL-22 and RegIIIγ. However, expression of the inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-1β, as well as iNOS, was significantly reduced following anti-GM-CS F treatment. Expression of the neutrophil chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2, but not the chemokines CC L2, CC L4, CXCL9, and CXCL10, was significantly reduced by anti-GM-CS F treatment. Consistent with a decrease in neutrophil-attractant chemokine expression, there were fewer neutrophils in histology sections and a reduction in the expression of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), a tissue anti-protease that protects against damage by secreted neutrophil elastase. These data indicate that GM-CS F plays a role in the inflammatory signaling network that drives neutrophil recruitment in response to C. difficile infection but does not appear to play a role in clearance of the infection.

Keywords: cytokine, chemokine, colitis, inflammation, bacteria, microbiome, innate immunity, epithelium

Introduction

Mucosal inflammation, especially during acute bacterial infections, involves the activation of numerous innate immunity pathways that result in the expression of inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL-6, IFNγ, and GM-CSF, as well as leukocyte chemotactic factors, including the chemokines CCL2, CCL4, CXCL1, and CXCL2.1–5 In response, neutrophils and monocytes and/or macrophages are recruited in high numbers. While toxin-producing bacterial pathogens such as Clostridium difficile can cause direct damage to the intestinal epithelium,6–8 the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells can also cause damage to the epithelial barrier that may contribute to the pathogenesis of the bacterial infection.1–5

Clostridium difficile infection of antibiotic-treated mice results in acute colitis characterized by severe intestinal histopathology and robust neutrophil influx and is associated with increased expression of numerous inflammatory cytokines, including GM-CSF.9–14 GM-CSF is a potent driver of mucosal inflammation in numerous settings, including the intestinal tract.15–17 GM-CSF can play a role in neutrophil recruitment during acute pulmonary inflammation (both chemical and microbial)18–21 and drive maximal production of TNFα and CXCL2 in response to pulmonary LPS challenge.18 Colonic IL-6 production during chemically-induced colitis has also been shown to be GM-CSF-dependent. 22 Thus, GM-CSF signaling can drive both the recruitment of inflammatory leukocytes as well as the production of inflammatory mediators during mucosal inflammation.

However, the role of GM-CSF in C. difficile infection may be pleiotropic because, in addition to the pro-inflammatory functions mentioned above, GM-CSF signaling also serves to protect the epithelium from damage during mucosal inflammation.22–25 Ablation of GM-CSF signaling can result in a significant increase in colonic histopathology, including colonic ulceration, during dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis.22,24 Furthermore, treatment of afflicted animals with exogenous GM-CSF is capable of reducing colonic ulceration in the same model.23 Inflammation and neutrophil influx are also key features of murine models of C. difficile infection.9–14,26–28 C. difficile toxins can elicit IL-1β, TNFα, CC, and CXC chemokine production from macrophages and epithelial cells in vitro, as well as under in vivo conditions.29–34 Other surface proteins of C. difficile have also been implicated in the induction of inflammatory cytokines.35 Despite our growing understanding of the pathways regulating C. difficile colitis, the role of GM-CSF signaling during this process remains poorly understood. In the current study, we examined the contribution of GM-CSF in promoting both cytokine expression and leukocyte recruitment during C. difficile colitis in a murine model, using a well-studied in vivo neutralizing GM-CSF monoclonal antibody (mAb, MP1-22E9) to interfere with GM-CSF signaling.18–20,36–38

Results

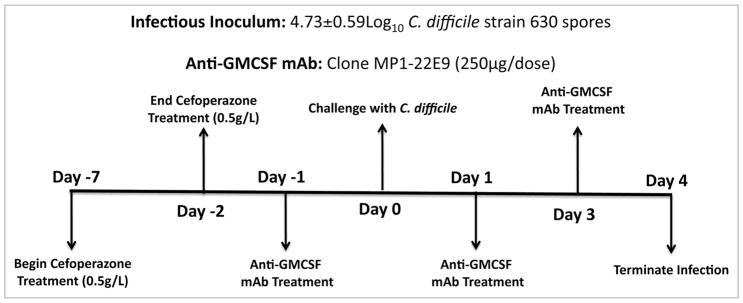

Expression of GM-CSF during C. difficile infection

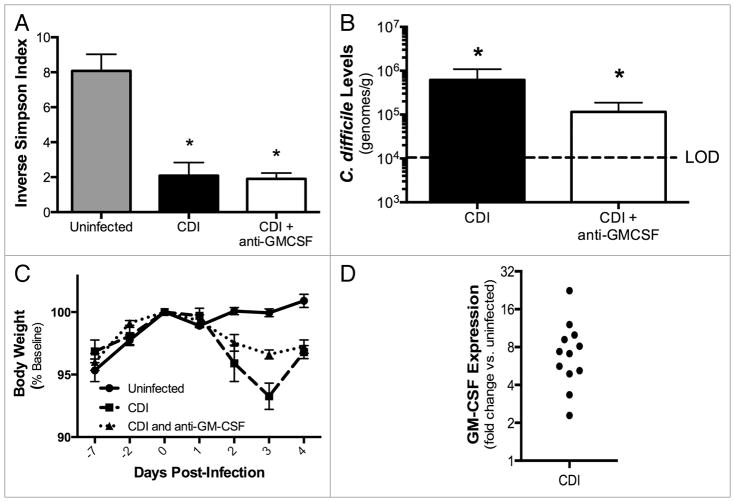

We used a C. difficile infection model adapted from a previously described mouse model of acute C. difficile infection.13 Briefly, mice received the broad-spectrum antibiotic cefoperazone in their drinking water for 5 d, were infected with spores from C. difficile strain 630 by oral gavage 2 d after the cessation of antibiotics and then followed for 4 d (Fig. 1). C. difficile 630 infection causes relatively mild disease, and this strain was chosen to permit investigation of both proinflammatory and epithelial-protective functions of GM-CSF. Cefoperazone treatment and C. difficile challenge resulted in a significant decrease in total bacterial diversity in the colon that persisted for at least one week post-antibiotic treatment (Fig. 2A) and the establishment of C. difficile colonization in the colon (Fig. 2B). Beginning one day post-infection, C. difficile-infected mice began to lose body weight (Fig. 2C). Additionally, there was a statistically significant increase in GM-CSF expression in the colon of C. difficile-infected mice compared with uninfected mice (Fig. 2D), which was not seen in mice treated only with cefoperazone (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Experimental approach and timeline.

Figure 2.

(A) Colonic microbiota diversity during C. difficile 630 infection (Day 4). (B) C. difficile 630 colonization of the colonic mucosa, as determined by C. difficile-specific qPCR (Day 4). LOD, Limit of Detection. (C) Change in body weight during C. difficile infection, expressed as percent of baseline body weight on day of infection. (D) Change in expression of GM-CS F following C. difficile 630 infection (Day 4) compared with uninfected mice. (A–C) Mice were treated as outlined in Figure 1. CDI, C. difficile infected. n = 8 mice per group. Data are the mean ± SE M *P < 0.05 compared with uninfected. (D) Mice were treated as outlined in Figure 1. n = 12 per group (infected and uninfected). P < 0.05 for dCt values of infected vs. uninfected.

Effect of anti-GM-CSF treatment on C. difficile infection and the intestinal epithelium

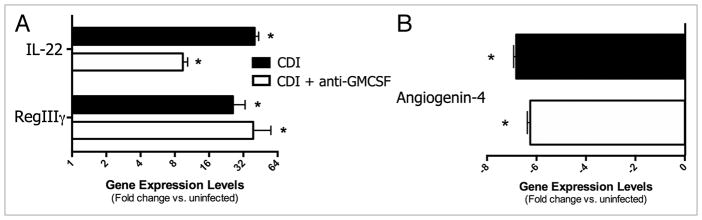

To begin to investigate the role of GM-CSF in the pathogenesis of C. difficile infection, mice were treated with a neutralizing anti-GM-CSF monoclonal antibody (MP1-22E9) every other day beginning one day prior to infection (Fig. 1). This treatment did not affect the low bacterial diversity in these mice (Fig. 2A), nor did it significantly alter the composition of the bacterial microbiome (data not shown). Although not statistically significant, there was a trend toward lower C. difficile colonization levels and more modest weight loss during the course of disease in mice treated with anti-GM-CSF mAb (Fig. 2B and C). C. difficile infection induced robust expression of the IL-22 pathway in the colonic mucosa, including induction of RegIIIγ (Fig. 3A). There was a trend toward lower IL-22 expression levels in anti-GM-CSF treated mice, but neither IL-22 nor RegIIIγ expression was significantly lower in these mice (Fig. 3A). Thus, treatment with anti-GM-CSF mAb did not exacerbate disease; rather, C. difficile colonization levels, weight loss and induction of the IL-22 pathway remained the same, if not slightly improved.

Figure 3.

Effect of anti-GM-CS F treatment on (A) IL-22, RegIIIγ and (B) angiogenin-4 expression in the colonic mucosa during C. difficile infection (Day 4). Mice were treated as outlined in Figure 1. CDI, C. difficile infected. Expression was measured by qPCR as outlined in the methods. n ≥ 8 mice per group. Data are the mean ± SE M *P < 0.05 compared with uninfected.

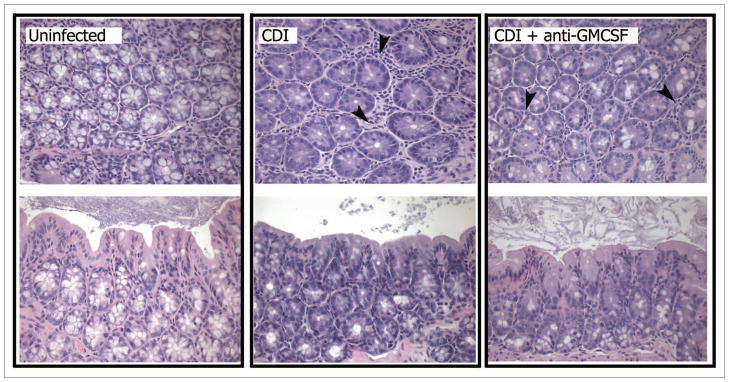

One of the other salient features of C. difficile infection in the colon is the destruction of goblet cells in the epithelium. This loss was observed in both levels angiogenin-4 expression (Fig. 3B) and histologically evident changes (Fig. 4). In the colon, angiogenin-4 is expressed solely by goblet cells in the crypts,39 and the expression of angiogenin-4 was significantly reduced in C. difficile-infected mice. Loss of goblet cells from colonic crypts was evident in histology sections, with a marked reduction in these cells (denoted by their vacuoles) observed in both transverse and oblique sections (Fig. 4). Treatment with anti-GM-CSF mAb did not significantly protect against loss of angiogenin-4 expression (Fig. 3B) or goblet cells (Fig. 4) that occurred during C. difficile infection.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of representative H&E-stained oblique and transverse sections of colonic crypts from uninfected (untreated), C. difficile 630 infected (Day 4), and C. difficile 630 infected, anti-GM-CS F treated (Day 4) mice. CDI, C. difficile infected. Mice were treated as outlined in Figure 1. Black arrows indicate infiltrating neutrophils. 400×.

Effect of anti-GM-CSF treatment on inflammation and neutrophil recruitment during C. difficile infection

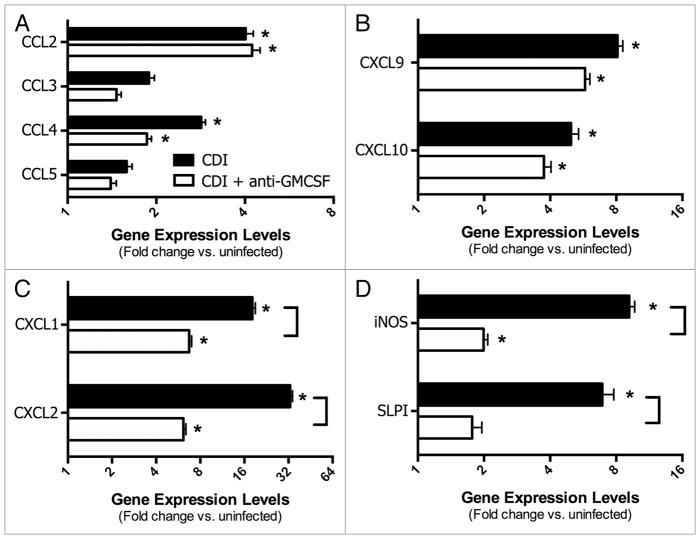

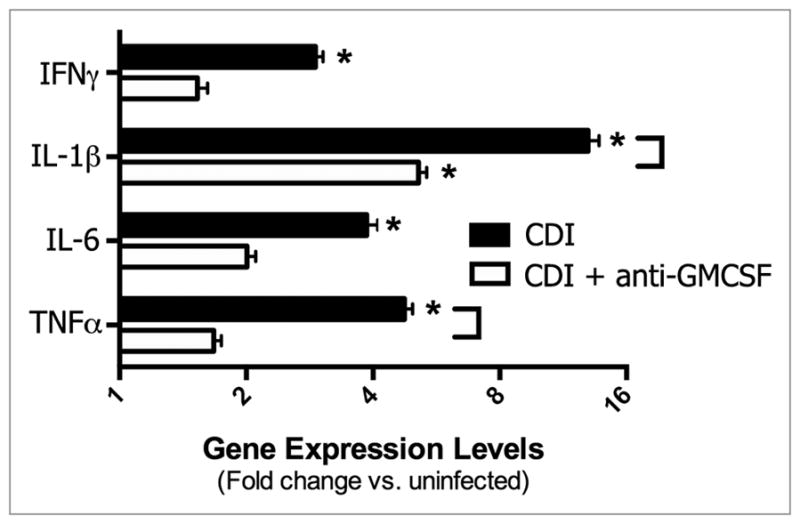

However, investigation into some of the specific inflammatory pathways associated with C. difficile infection revealed a role for GM-CSF in driving inflammatory cell recruitment, most notably neutrophils. C. difficile 630 infection induced significant expression of the inflammatory cytokines IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα in the colon mucosa at four days post-infection (Fig. 5). Treatment of C. difficile infected mice with anti-GM-CSF mAb resulted in significantly lower expression of IL-1β and TNFα (Fig. 5). There was no significant induction of IL-12, IL-23, IL-17, IL-10, or TGF-β in either group of infected mice (data not shown). Consistent with the leukocytic infiltrates evident in histological sections of C. difficile 630 infected mice (Fig. 4), there was a significant increase in expression of the CC chemokines CCL2 (MCP-1) and CCL4 (MIP-1α) and the IFNγ-inducible non-ELR CXC chemokines CXCL9 (MIG) and CXCL10 (IP10) (Fig. 6A and B). Anti-GM-CSF treatment had no effect on expression of these chemokines. In contrast to CCL2, CCL4, CXCL9, and CXCL10, anti-GM-CSF treatment significantly reduced expression of the ELR+ CXC chemokines CXCL1 (KC) and CXCL2 (MIP-2) (Fig. 6C). ELR+ CXC chemokines are predominantly neutrophil chemotactic factors and contain a conserved amino acid sequence motif (glutamic acid-leucine-arginine, i.e., E-L-R) that immediately precedes the first cysteine residue near the N-terminal end and confers binding specificity to specific CXC chemokine receptors. Expression of both of these ELR+ CXC chemokines in the colon following C. difficile infection was also associated with the influx of neutrophils into the parenchyma (Fig. 4). Consistent with the lower, but still significant, expression of CXCL1 and CXCL2 in anti-GM-CSF treated mice, neutrophils were still evident in colonic mucosal sections, but their numbers were reduced (Fig. 4).

Figure 5.

Effect of anti-GM-CS F treatment on inflammatory cytokine expression in the colonic mucosa during C. difficile infection (Day 4). Mice were treated as outlined in Figure 1. Expression was measured by qPCR as outlined in the methods. CDI, C. difficile infected. n = 8 mice per group. Data are the mean ± SE M *P < 0.05 compared with uninfected. Brackets P < 0.05 in comparing CDI vs. CDI+anti-GMCS F.

Figure 6.

(A–C) Effect of anti-GM-CS F treatment on chemokine expression in the colonic mucosa during C. difficile infection (Day 4). (D) Effect of anti-GM-CS F treatment on iNOS and SLPI expression in the colonic mucosa during C. difficile infection (Day 4). (A–D) Mice were treated as outlined in Figure 1. Expression was measured by qPCR as outlined in the methods. CDI, C. difficile infected. n = 8 mice per group. Data are the mean ± SE M *P < 0.05 compared with uninfected. ]Brackets P < 0.05 in comparing CDI vs. CDI+anti-GMCS F.

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is often associated with host antimicrobial responses, and can be expressed by a variety of cells including neutrophils40,41 and intestinal epithelial cells.42 iNOS was expressed in colonic tissue following C. difficile infection concomitant with the development of inflammation and neutrophil influx (Fig. 4). Anti-GM-CSF treatment also resulted in a significant decrease in iNOS expression (Fig. 6D).

Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), a well-documented inhibitor of neutrophil elastase and other serine proteases, is produced by epithelial cells and can protect against neutrophil-mediated protease damage.43–47 Following C. difficile infection, SLPI expression is significantly upregulated in the colonic mucosa (Fig. 6D). However, treatment with anti-GM-CSF significantly reduced expression of SLPI, concomitant with the reduced neutrophil influx in these mice (Fig. 6D).

Discussion

This is the first reported investigation of the role of GM-CSF in the cytokine network that regulates inflammation following C. difficile infection. In the current study, we observed reduced ELR+ CXC chemokine expression in addition to evidence of decreased neutrophil recruitment following anti-GM-CSF treatment. GM-CSF is a potent driver of mucosal inflammation in other disease settings, including the intestinal tract,15–17 but has not been investigated for the pathogenesis of C. difficile, a toxin-producing bacteria with virulence mechanisms distinct from attaching and effacing enteric bacteria. GM-CSF has been reported to promote neutrophil recruitment during acute pulmonary inflammation18–21 and is also required for full recruitment of neutrophils and production of CXCL1 (KC) in an experimental model of otitis media.48 Within the gut, GM-CSF has also been shown to promote neutrophil recruitment during 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-colitis.49 Additionally, one study suggests that GM-CSF can function directly as a chemoattractant for neutrophils.49 While we have demonstrated that GM-CSF is expressed in the colon, and previous studies have demonstrated colon-localized effects following intraperitoneal injection of the anti-GM-CSF mAb used in the current study,50 we have no evidence in this study that the site of activity of our anti-GM-CSF mAb is the colon itself. GM-CSF is a critical factor for the survival of infiltrating neutrophils in a tissue, protecting them against apoptosis, but it also plays a role in the differentiation of neutrophils from bone marrow-derived precursors. Thus, an important site of GM-CSF activity during C. difficile infection may be the bone marrow. Altogether, our data strongly support the concept that GM-CSF can regulate neutrophil chemokine expression and neutrophil recruitment during C. difficile colitis although its activity may include extra-intestinal regulation of neutrophil biology.

In addition to reduced ELR+ CXC chemokine expression, we also observed decreased expression of inflammatory cytokines, most notably TNFα, during C. difficile colitis following anti-GM-CSF treatment. TNFα expression has been demonstrated to be largely dependent upon GM-CSF signaling in chemical19 and microbial18 models of acute pulmonary inflammation. GM-CSF also promotes TNFα production during middle-ear inflammation.48 Inflammatory cytokine expression during chemically-induced colitis is also dependent upon GM-CSF.22 Consistent with other reports, our data strongly suggest that GM-CSF promotes inflammatory cytokine expression during C. difficile colitis.

Numerous studies have reported an epithelial-protective function for GM-CSF during mucosal inflammation.22–25,51 In the absence of GM-CSF, colonic ulceration and overall intestinal pathology in response to DSS is significantly increased.22,24 Additionally, during Citrobacter rodentium infection, GM-CSF serves to protect against the development of severe intestinal pathology.51 In the current study, however, we did not observe increased epithelial damage during C. difficile infection following anti-GM-CSF treatment or further reduction in expression of the goblet cell-associated antimicrobial peptide angiogenin-4,39 suggesting colonic goblet cells were not under additional stress following anti-GM-CSF treatment. Altogether, this may reflect a difference in the nature of the primary source of epithelial damage during infection, C. difficile toxins,6–8 compared with other mechanisms of epithelial damage.

One model that could explain the association between reduced neutrophil recruitment and reduced cytokine and chemokine expression seen following anti-GM-CSF treatment is that neutrophils may also be a cellular source of inflammatory cytokines during C. difficile infection. Neutrophil recruitment into the colonic mucosa and production of a “storm” of inflammatory cytokines are key features of the pathogenesis of the disease.9–14,26–28 C. difficile toxins TcdA and TcdB, as well as other factors from C. difficile, can elicit IL-1β, TNFα, CC, and CXC chemokine production from macrophages and epithelial cells in vitro, but neutrophils have not been investigated as a cellular source.29–35 Neutrophils are capable of producing IL-1β and TNFα, as well as chemokines.52,53 Additionally, GM-CSF not only serves to prevent neutrophil apoptosis, but also modifies neutrophil behavior and can promote the production of neutrophil chemokines.52,54 However, other studies in our laboratory, using anti-Gr1 to deplete Gr1+ cells during C. difficile VPI 10463 infection in mice, found no change in the levels of IL-1β, TNFα or CXCL1 expression following anti-Gr-1 treatment (McDermott et al., in preparation). One caveat of this observation is that this strain of C. difficile produces higher levels of toxins, resulting in a more severe disease with more extensive epithelial damage.10,13,14 Thus, additional cellular pathways of IL-1β, TNFα or CXCL1 expression may be induced when toxin levels are higher.

Methods

Bacterial growth conditions and spore preparations

C. difficile strain 630 in these studies was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC 1382) and was cultured in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products). Strain 630 was originally isolated from a patient with a severe transmissible C. difficile infection in Zurich, Switzerland in 1982. The genome of this strain has been fully sequenced by the Wellcome Sanger Trust Institute: http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/downloads/bacteria/clostridium-difficile.html

For routine growth and maintenance, the isolates were cultured on BHIS (brain-heart infusion broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract and 0.1% cysteine) plates. Spore stocks for C. difficile 630 were produced as follows: An early spore preparation was used to reconstitute vegetative cells by plating on BHIS + 0.1% taurocholate. An isolated colony was used to inoculate an overnight culture of Columbia broth. Two ml of the overnight culture was then used to inoculate 40 ml of Clospore broth,55 upon which the culture was allowed to grow for seven days. Cultures were then washed at least four times to remove vegetative cell debris. Spore stocks were stored in water at 4 °C until use.

Animals and housing

All experiments were performed using male C57BL/6 mice 5–9 wk of age and conducted under a protocol approval of the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA) at the University of Michigan. All mice in this study were obtained from an in-house breeding colony at the University of Michigan founded from breeders obtained from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were given autoclaved water and food ad libitum, and were housed with autoclaved bedding. Mice were housed in a facility with alternating 12-h cycles of light and dark. All cage changes and animal manipulations were performed in a laminar flow hood.

Antibiotic treatment and C. difficile infection

Mice were treated with cefoperazone (0.5 g/L) in their drinking water for five days in order to permit C. difficile infection. Following a 2-d recovery period, animals were challenged with 4.73 ± 0.59 log10 630 spores as described previously.13 Following challenge, the inoculum was serially diluted and plated on Taurocholate Cefoxitin Cycloserine Fructose Agar (TCCFA) plates anaerobically in order to confirm the dosage. All animals were monitored for weight change during the course of the experiment, and were monitored for signs of severe C. difficile infection (lethargy, hunched posture, >20% weight loss) and were euthanized if meeting any of these criteria. Uninfected animals received neither antibiotic treatment, nor C. difficile challenge. Samples were collected at four days post-infection.

Anti-GM-CSF treatment

Animals were given three intraperitoneal injections of anti-GM-CSF mAb (clone MP1–22E9). Each mouse received 250 μg per injection, and injections were given every 48 h beginning 24 h prior to infection.38,50

Tissue sample collection and histology

Colonic tissue samples (1 cm2) were either flash-frozen for subsequent DNA isolation, or stored in RNAlater (Ambion) for subsequent RNA extraction. For the generation of histological sections, colonic tissue was fixed in 10% formalin overnight and was then transferred to 70% ethanol. The tissues were processed, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and used to prepare hematoxylin and eosin stained slides (McClinchey Histology Labs Inc). Representative images were photographed on an Olympus BX40 light microscope (Olympus Corporation) using a QImaging MicroPublisher RTV 5.0 5 megapixel camera (QImaging Corporation) at a total magnification of 400×. Images were acquired using QCapture Suite PLUS (QImaging Corporation) version 3.1.3.10. Image and panel assembly was performed in Adobe Photoshop CS5, version 12.0. Image processing was restricted to global adjustments of brightness, contrast, and image size.

Quantification of C. difficile colonization

Tissue-associated C. difficile colonization was assessed by C. difficile-specific qPCR using DNA isolated from 1 cm2 tissue samples excised near the center of the colon. The C. difficile species-specific qPCR was performed as described previously.14 Briefly, each reaction was performed in a total volume of 10 μl. Each reaction included 6.25 pmol F/R tcdB primers, 1 pmol tcdB probe, and 2 μl template. Cycling conditions for the reaction were as follows: Activation: 1 cycle, 95 °C for 15 min. Cycling: 45 cycles. Each cycle consists of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 10 s. Hold: Hold at 72 °C for 30 s. Raw Ct values were normalized to signal from a single-copy host internal control gene to generate dCt values.14,56 All reactions were run on a Roche LightCycler 480. Probe and primer sequences are as follows: tcdB-F: 5′-GAA-AGT-CCA-AGT-TTA-CGC-TCA-AT-3′; tcdB-R: 5′-GCT-GCA-CCT-AAA-CTT-ACA-CCA-3′; tcdB Probe: 5′-/5HEX/ACA-GAT-GCA-GCC-AAA-GTT-GTT-GAA-TT/3BHQ_1/-3′.

RNA isolation and expression analysis

Colonic RNA was isolated as described previously.9 Briefly, colonic tissue was homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies), and RNA was purified using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s specifications. The resulting RNA was assessed for quality and concentration using an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and a Nanodrop instrument (Thermo Fisher). The RT2 First Strand kit (Qiagen) was used to generate cDNA, and colonic gene expression was then determined using RT2 Profiler PCR assays (Qiagen). All reactions were run on a Roche LightCycler 480. Cross-plate normalization was performed as described previously,9,57 and dCt values were calculated by subtracting the average Ct value derived from two internal control genes from the Ct value of the gene in question.58 The 2-ddCt method was then utilized to calculate fold change between infected groups and uninfected controls.56

Microbiome analysis

The DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen) was used to extract genomic DNA from colonic tissue samples. The extraction was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions except for the following modifications: adding a bead-beating step using UltraClean fecal DNA bead tubes (Mo Bio Laboratories), doubling the amount of ATL buffer and the proteinase K used in the protocol, and decreasing by half the amount of the AE buffer used to elute the DNA. Subsequently, the V3, V4, and V5 hyper-variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene in each of the samples were targeted for amplification with the 357F and 929R primer sets.59 Amplicons were purified with the Agencourt AMPure XP PCR purification system (Beckman Coulter), and quantified with the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit (Life Technologies) to obtain an equal pool for pyrosequencing. They were then sequenced on a Roche 454 GS Junior Titanium platform according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Bacterial 16S sequences were first processed using the microbial ecology software suite mothur60 to generate operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 3%, i.e., species level of difference. These data, in the form of the .shared file, were then imported into the R software and analyzed using the R-package vegan. The inverse Simpson diversity measure was calculated using the function diversity().

Statistical analysis

For the initial assessment of GM-CSF expression during C. difficile colitis, statistical significance was determined via an unpaired two-tailed t test comparing dCt values from uninfected and C. difficile infected mice. For all other analyses of colonic gene expression, data sets were first checked by outlier analysis and then statistically significant changes were identified using a One-Way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test comparing normalized dCt values from uninfected, C. difficile infected, and anti-GM-CSF treated and C. difficile infected animals. Statistically significant changes in the inverse Simpson index and C. difficile colonization were also determined using One-Way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. Significance was set at P < 0.05 in all analyses.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge John Erb-Downward, Amir Sadighi Akha, and Dayana Rojas for their support, discussions, and contributions to this project. This work was in part supported by NIH grants U19 AI090871 (G.B.H. and V.B.Y.), P30 DK034933 (G.B.H. and V.B.Y.), and the Host Microbiome Initiative (HMI) of the University of Michigan Medical School (G.B.H. and V.B.Y.).

Abbreviations

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor

- TNFα

Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha

- IL

Interleukin

- IFNγ

Interferon Gamma

- CCL

Chemokine (C-C Motif) Ligand

- CXCL

Chemokine (C-X-C Motif) Ligand

- ELR

conserved amino sequence motif (glutamic acid-leucine-arginine, i.e., E-L-R) in some CXC chemokines that immediately precedes the first cysteine residue near the amino-terminal end

- iNOS

Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS2)

- RegIIIγ

Regenerating Islet-Derived 3 Gamma

- SLPI

Secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor

- Tgfβ1

Transforming growth Factor beta 1

- Ang4

Angiogenin 4

- TCCFA

Taurocholate Cycloserine Cefoxitin Fructose Agar

- DSS

Dextran Sodium Sulphate

- TNBS

2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

References

- 1.Buffie CG, Pamer EG. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance against intestinal pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:790–801. doi: 10.1038/nri3535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:383–90. doi: 10.1038/ni.2025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ni.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabady RL, McCormick BA. Control of neutrophil inflammation at mucosal surfaces by secreted epithelial products. Front Immunol. 2013;4:220. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00220. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2013.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brazil JC, Louis NA, Parkos CA. The role of polymorphonuclear leukocyte trafficking in the perpetuation of inflammation during inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1556–65. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281f54e. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281f54e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fournier BM, Parkos CA. The role of neutrophils during intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:354–66. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/mi.2012.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britton RA, Young VB. Interaction between the intestinal microbiota and host in Clostridium difficile colonization resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.04.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rupnik M, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:526–36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voth DE, Ballard JD. Clostridium difficile toxins: mechanism of action and role in disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:247–63. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.247-263.2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.18.2.247-263.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadighi Akha AA, Theriot CM, Erb-Downward JR, McDermott AJ, Falkowski NR, Tyra HM, Rutkowski DT, Young VB, Huffnagle GB. Acute infection of mice with Clostridium difficile leads to eIF2α phosphorylation and pro-survival signalling as part of the mucosal inflammatory response. Immunology. 2013;140:111–22. doi: 10.1111/imm.12122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/imm.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Katchar K, Goldsmith JD, Nanthakumar N, Cheknis A, Gerding DN, Kelly CP. A mouse model of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1984–92. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasegawa M, Yamazaki T, Kamada N, Tawaratsumida K, Kim YG, Núñez G, Inohara N. Nucleotidebinding oligomerization domain 1 mediates recognition of Clostridium difficile and induces neutrophil recruitment and protection against the pathogen. J Immunol. 2011;186:4872–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003761. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1003761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarchum I, Liu M, Shi C, Equinda M, Pamer EG. Critical role for MyD88-mediated neutrophil recruitment during Clostridium difficile colitis. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2989–96. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00448-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00448-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theriot CM, Koumpouras CC, Carlson PE, Bergin II, Aronoff DM, Young VB. Cefoperazone-treated mice as an experimental platform to assess differential virulence of Clostridium difficile strains. Gut Microbes. 2011;2:326–34. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19142. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/gmic.19142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeves AE, Theriot CM, Bergin IL, Huffnagle GB, Schloss PD, Young VB. The interplay between microbiome dynamics and pathogen dynamics in a murine model of Clostridium difficile Infection. Gut Microbes. 2011;2:145–58. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.3.16333. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/gmic.2.3.16333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Däbritz J. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor and the intestinal innate immune cell homeostasis in Crohn’s disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G455–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00409.2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00409.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton JA. Colony-stimulating factors in inflammation and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:533–44. doi: 10.1038/nri2356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Asthma: the importance of dysregulated barrier immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:3125–37. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343730. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eji.201343730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puljic R, Benediktus E, Plater-Zyberk C, Baeuerle PA, Szelenyi S, Brune K, Pahl A. Lipopolysaccharideinduced lung inflammation is inhibited by neutralization of GM-CSF. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlahos R, Bozinovski S, Chan SP, Ivanov S, Lindén A, Hamilton JA, Anderson GP. Neutralizing granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor inhibits cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:34–40. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1794OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200912-1794OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozinovski S, Jones J, Beavitt SJ, Cook AD, Hamilton JA, Anderson GP. Innate immune responses to LPS in mouse lung are suppressed and reversed by neutralization of GM-CSF via repression of TLR-4. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L877–85. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00275.2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00275.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balloy V, Chignard M. The innate immune response to Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:919–27. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.07.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Y, Hunt NH, Bao S. The role of granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor in acute intestinal inflammation. Cell Res. 2008;18:1220–9. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cr.2008.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernasconi E, Favre L, Maillard MH, Bachmann D, Pythoud C, Bouzourene H, Croze E, Velichko S, Parkinson J, Michetti P, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor elicits bone marrow-derived cells that promote efficient colonic mucosal healing. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:428–41. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21072. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egea L, McAllister CS, Lakhdari O, Minev I, Shenouda S, Kagnoff MF. GM-CSF produced by non-hematopoietic cells is required for early epithelial cell proliferation and repair of injured colonic mucosa. J Immunol. 2013;190:1702–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202368. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1202368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cakarova L, Marsh LM, Wilhelm J, Mayer K, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Lohmeyer J, Herold S. Macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces epithelial expression of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: impact on alveolar epithelial repair. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:521–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1837OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200812-1837OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buffie CG, Jarchum I, Equinda M, Lipuma L, Gobourne A, Viale A, Ubeda C, Xavier J, Pamer EG. Profound alterations of intestinal microbiota following a single dose of clindamycin results in sustained susceptibility to Clostridium difficile-induced colitis. Infect Immun. 2012;80:62–73. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05496-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.05496-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jarchum I, Liu M, Lipuma L, Pamer EG. Toll-like receptor 5 stimulation protects mice from acute Clostridium difficile colitis. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1498–503. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01196-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01196-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasegawa M, Kamada N, Jiao Y, Liu MZ, Núñez G, Inohara N. Protective role of commensals against Clostridium difficile infection via an IL-1β-mediated positive-feedback loop. J Immunol. 2012;189:3085–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200821. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1200821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng J, Hirota SA, Gross O, Li Y, Ulke-Lemee A, Potentier MS, Schenck LP, Vilaysane A, Seamone ME, Feng H, et al. Clostridium difficile toxin-induced inflammation and intestinal injury are mediated by the inflammasome. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:542–52. e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun X, Wang H, Zhang Y, Chen K, Davis B, Feng H. Mouse relapse model of Clostridium difficile infection. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2856–64. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01336-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01336-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun X, He X, Tzipori S, Gerhard R, Feng H. Essential role of the glucosyltransferase activity in Clostridium difficile toxin-induced secretion of TNF-alpha by macrophages. Microb Pathog. 2009;46:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2009.03.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JM, Kim JS, Jun HC, Oh YK, Song IS, Kim CY. Differential expression and polarized secretion of CXC and CC chemokines by human intestinal epithelial cancer cell lines in response to Clostridium difficile toxin A. Microbiol Immunol. 2002;46:333–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02704.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castagliuolo I, Keates AC, Wang CC, Pasha A, Valenick L, Kelly CP, Nikulasson ST, LaMont JT, Pothoulakis C. Clostridium difficile toxin A stimulates macrophage-inflammatory protein-2 production in rat intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:6039–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castagliuolo I, Kelly CP, Qiu BS, Nikulasson ST, LaMont JT, Pothoulakis C. IL-11 inhibits Clostridium difficile toxin A enterotoxicity in rat ileum. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G333–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.2.G333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan A, Lynch M, Smith SM, Amu S, Nel HJ, McCoy CE, Dowling JK, Draper E, O’Reilly V, McCarthy C, et al. A role for TLR4 in Clostridium difficile infection and the recognition of surface layer proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002076. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002076. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wuthrich M, Filutowicz HI, Warner T, Deepe GS, Jr, Klein BS. Vaccine immunity to pathogenic fungi overcomes the requirement for CD4 help in exogenous antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells: implications for vaccine development in immune-deficient hosts. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1405–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.20030109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deepe GS, Jr, Gibbons R, Woodward E. Neutralization of endogenous granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor subverts the protective immune response to Histoplasma capsulatum. J Immunol. 1999;163:4985–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook AD, Pobjoy J, Steidl S, Dürr M, Braine EL, Turner AL, Lacey DC, Hamilton JA. Granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor is a key mediator in experimental osteoarthritis pain and disease development. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R199. doi: 10.1186/ar4037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/ar4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forman RA, deSchoolmeester ML, Hurst RJ, Wright SH, Pemberton AD, Else KJ. The goblet cell is the cellular source of the anti-microbial angiogenin 4 in the large intestine post Trichuris muris infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Virtuoso LP, Harden JL, Sotomayor P, Sigurdson WJ, Yoshimura F, Egilmez NK, Minev B, Kilinc MO. Characterization of iNOS(+) Neutrophil-like ring cell in tumor-bearing mice. J Transl Med. 2012;10:152. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-10-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolpen M, Bjarnsholt T, Moser C, Hansen CR, Rickelt LF, Kühl M, Hempel C, Pressler T, Høiby N, Jensen PO. Nitric oxide production by polymorphonuclear leucocytes in infected cystic fibrosis sputum consumes oxygen. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;177:310–9. doi: 10.1111/cei.12318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cei.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallance BA, Deng W, De Grado M, Chan C, Jacobson K, Finlay BB. Modulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by the attaching and effacing bacterial pathogen citrobacter rodentium in infected mice. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6424–35. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6424-6435.2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.70.11.6424-6435.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Si-Tahar M, Merlin D, Sitaraman S, Madara JL. Constitutive and regulated secretion of secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor by human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1061–71. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70359-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reardon C, Lechmann M, Brüstle A, Gareau MG, Shuman N, Philpott D, Ziegler SF, Mak TW. Thymic stromal lymphopoetin-induced expression of the endogenous inhibitory enzyme SLPI mediates recovery from colonic inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:223–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taggart CC, Cryan SA, Weldon S, Gibbons A, Greene CM, Kelly E, Low TB, O’neill SJ, McElvaney NG. Secretory leucoprotease inhibitor binds to NF-kappaB binding sites in monocytes and inhibits p65 binding. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1659–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050768. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.20050768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mizoguchi E, Xavier RJ, Reinecker HC, Uchino H, Bhan AK, Podolsky DK, Mizoguchi A. Colonic epithelial functional phenotype varies with type and phase of experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:148–61. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00665-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nukiwa T, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, Kikuchi T. Secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor and lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:849–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00772.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kariya S, Okano M, Higaki T, Makihara S, Haruna T, Eguchi M, Nishizaki K. Neutralizing antibody against granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor inhibits inflammatory response in experimental otitis media. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1514–8. doi: 10.1002/lary.23795. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/lary.23795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khajah M, Millen B, Cara DC, Waterhouse C, McCafferty DM. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF): a chemoattractive agent for murine leukocytes in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:945–53. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0809546. http://dx.doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0809546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Han G, Wang K, Liu G, Wang R, Xiao H, Li X, Hou C, Shen B, Guo R, et al. Tumor-derived GM-CSF promotes inflammatory colon carcinogenesis via stimulating epithelial release of VEGF. Cancer Res. 2014;74:716–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirata Y, Egea L, Dann SM, Eckmann L, Kagnoff MF. GM-CSF-facilitated dendritic cell recruitment and survival govern the intestinal mucosal response to a mouse enteric bacterial pathogen. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:151–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi GW, Andrews DF, 3rd, Lilly MB, Singer JW, Alderson MR. Effect of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-3 on interleukin-8 production by human neutrophils and monocytes. Blood. 1993;81:357–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scapini P, Lapinet-Vera JA, Gasperini S, Calzetti F, Bazzoni F, Cassatella MA. The neutrophil as a cellular source of chemokines. Immunol Rev. 2000;177:195–203. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17706.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-065X.2000.17706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brach MA, deVos S, Gruss HJ, Herrmann F. Prolongation of survival of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is caused by inhibition of programmed cell death. Blood. 1992;80:2920–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez J, Springthorpe VS, Sattar SA. Clospore: a liquid medium for producing high titers of semi-purified spores of Clostridium difficile. J AOAC Int. 2011;94:618–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sadighi Akha AA, Harper JM, Salmon AB, Schroeder BA, Tyra HM, Rutkowski DT, Miller RA. Heightened induction of proapoptotic signals in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress in primary fibroblasts from a mouse model of longevity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30344–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.220541. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.220541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:H0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao J, Schloss PD, Kalikin LM, Carmody LA, Foster BK, Petrosino JF, Cavalcoli JD, VanDevanter DR, Murray S, Li JZ, et al. Decade-long bacterial community dynamics in cystic fibrosis airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5809–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120577109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1120577109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–41. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]