Abstract

Metabolomics applications of differential mobility spectrometry-mass spectrometry have largely concentrated on targeted assays and the removal of isobaric or chemical interferences from the signals of a small number of analytes. In this publication, we systematically investigated the application range of a DMS-MS method for metabolomics, using over 800 authentic metabolite standards as the test set. The coverage achieved with the DMS-MS platform was comparable to chromatographic methods. High orthogonality was observed between hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) and the isopropanol-mediated DMS separation, while previously observed similarities were confirmed for the DMS platform and reversed-phase liquid chromatography. We describe the chemical selectivity observed for selected sub-sets of the metabolite test set, such as lipids, amino acids, nucleotides and organic acids. Furthermore, we rationalize the behavior and separation of isomeric, aromatic acids, bile acids and other metabolites.

Keywords: Differential mobility spectrometry, mass spectrometry, metabolomics, lipidomics, selectivity

1. Introduction

In October 2017, the search term “ion mobility spectrometry” (IM) yielded over 4,500 results in SciFinder™. More than 55% of these publications also deal with mass spectrometry (MS). Over the past few years, the popularity of this technique and its application in metabolomics have been boosted by the commercialization of integrated IM-MS platforms based on travelling wave, drift tube and differential mobility spectrometry (DMS) [1,2].

The DMS cell consists of two parallel electrodes located in the atmospheric pressure region of the MS instrument between ion source and vacuum interface. The trajectories of ions entering the cell are altered by a strong electric field between the two electrodes (separation voltage, SV), causing the ions to be neutralized at the electrodes. The compensation voltage (COV, sometimes also abbreviated as CV) is a compound-specific voltage that, when superimposed on the SV, restores the respective ion trajectory and allows the ion to migrate through the DMS cell and into the MS. DMS selectivity can be enhanced by the introduction of chemical modifiers that are infused into the DMS cell and engage in clustering-declustering processes with the analyte [3].

DMS in particular has been effectively utilized in applications involving carbohydrates [4–6] lipids [7,8], drugs [9,10] and other metabolites [11–13]. In most of these applications, the DMS-MS is coupled to an HPLC separation and the number of analytes ranges between two and ten. For such applications, method development is focused on identifying conditions under which the targeted analytes migrate at distinct compensation voltages (COVs), thus allowing them to be detected and analyzed by MS without interference from chemical noise or co-eluting isobars.

Despite several success stories of DMS in metabolomics, the application range of this technique is not fully understood. Systematic studies investigating the metabolome selectivity of DMS are required. Relating the findings to high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) results will help to fully realize the potential of DMS for improving the selectivity and efficiency (speed, peak capacity) of current assays. Importantly, we must assess its utility for non-targeted applications. We are envisioning both the development of hyphenated, multi-dimensional separations involving HPLC, DMS and MS and the potential of applying DMS as a stand-alone technique to separate metabolites prior to MS detection.

In this study, we evaluated the behavior of a diverse set of metabolites using a generic DMS-MS method and a library of 808 authentic standards [14]. We determined the test set coverage in positive and negative ionization mode and probed the relationship between COV and HPLC retention factors. We attempt to describe and rationalize the chemical selectivity of the DMS-MS platform for a variety of library sub-sets such as lipids, amino acids and nucleotides. Finally, we present selected isobar separations that were achieved using isopropanol as the modifier.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and solvents

LC-MS grade solvents acetonitrile (ACN), methanol (MeOH), isopropanol (iPrOH) and water were purchased from Millipore and Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 808 metabolite standards were purchased individually from commercial suppliers. Every standard was assigned to a sub-group according to its chemical properties. The groups were (number of metabolites in parenthesis): Organic acids (193), lipids and related compounds (144), phosphate-containing metabolites (91), amino acids (84), amines (61), (poly-)alcohols (39), carbohydrates (33), nucleosides (31), sulfates and sulfonates (11), and “not defined” (122). For DMS-MS analysis, we prepared library samples by equally distributing the groups between 20 mixtures so that every sample contained a) at least one representative of each group and b) only non-isobaric compounds. The final mixtures contained between 36 and 42 compounds at approximately 25 ng/μL in ACN/H2O (80:20 v/v) [14]. Samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis.

2.2. Instrumentation

The DMS-MS experiments were carried out on a Sciex 5600+ Triple TOF quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Sciex, Framingham, MA) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source and SelexION differential mobility cell. Isopropanol was used as the chemical modifier and introduced with the curtain gas flow. A Shimadzu Nexera X2 UHPLC system with dual pumps, degasser and thermostated autosampler (4 °C) was coupled to the MS instrument to perform automated sample introduction and provide a homogenous flow of the binary solvent mixture. Solvent A was H2O (50 mM NH4OAc), solvent B was ACN. Unless otherwise noted, direct infusion experiments were conducted by injecting 40 μL of sample into an LC flow of 20 μL/min (75% B) and collecting MS data for 3 minutes after 30 seconds of wait time.

For the COV ramping experiments, the sample was continuously infused at SV=3.0 kV while the COV was increased in steps of 0.33 V/s (“COV ramp mode”). The modifier concentration in the curtain gas was 1.5% and the resolution enhancement (“throttle”) gas (RG) was injected at a rate of 26 (arbitrary units). A range of 60 V (−50 V to +10 V) was covered over 3 minutes. MS data were acquired continuously in TOF scan mode. The compound-specific COVs were determined from the peak apex of the main peak in the extracted ion trace (XIC) of the ionograms (Fig. S1, Supplementary information).

Each injection was followed by a two-minute wash step at 200 μL/min to prevent carry-over. The necessary flow rate and duration of the wash step to ensure that no remaining sample was present in the lines had been determined in previous experiments (data not shown). In order to prevent electric discharge due to contamination of the DMS, the electrodes were cleaned as suggested by the manufacturer between the positive and negative mode runs. Briefly, the cleaning steps included abrasive powder and water, sonicating in methanol, and drying in a stream of nitrogen.

2.3. Data acquisition and analysis

AB Sciex Analyst Version TF 1.7.1 and AB Sciex PeakView Version 2.2 were used to control the instrument and perform data evaluation. Additional data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 and IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24.0.0.0. For statistical analyses, probability thresholds are 0.05 unless otherwise noted.

Pearson’s correlation analysis was employed to investigate correlations between variables. Analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons was used to compare mean values between metabolite groups.

Molecular descriptors were retrieved from the Human Metabolome Database [15] and the Chemical Abstracts Service online repository of the American Chemical Society (accessed via scifinder.cas.org) between November 2015 and November 2017 and represent calculated values. HPLC reference data are accessible in the supplementary information of [14].

2.4. Compliance with ethical standards

The authors declare that they have no financial and no non-financial conflicts of interest. This work utilized only commercially available chemicals and did not involve samples or procedures requiring approval by an institutional review board and informed consent.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Application range and general observations

Coverage

The first objective of this study was to determine the application range and metabolite coverage of a differential mobility spectrometry – mass spectrometry platform under conditions not optimized for any particular separation. In positive mode, optimum compensation voltages were determined for 529 metabolites. This equals a test set coverage of 65 % and is comparable to HPLC methods [11]. Metabolites with two or three adducts accounted for 499 out of 1,021 COVs determined in positive mode. All four major adduct types (H+, Na+, NH4+, water loss) were detected for 55 metabolites (Fig. 1a). 494 COVs were determined in negative mode, with 369 originating from deprotonated species and 127 from chlorine adducts. Overall coverage was 407 metabolites or 50% of the test set.

Fig. 1. Test set coverage achieved with the DMS-MS platform in positive ionization mode.

a 1,021 compensation voltages (COV) were determined, corresponding to 529 metabolites. b Distribution of adduct types across the positive mode separation space.

Peak capacity and COV spread

For this experiment, the theoretical peak capacity (PC) was 30, based on a scanned COV range of 60 and an average peak width at half maximum of 2.0 V. The real PC in negative mode was determined to be 22, based on the distance between maximum and minimum observed COV. The separation was less efficient in positive mode (PC=18). Peak widths were identical and the PC difference was accounted for solely by a 20% decreased COV range in positive mode (36 V compared to 44 V in negative mode).

Adduct types

Fig. 1b plots the COV optima determined in positive mode against the accurate mass of the neutral metabolites. The COV increases with molecular mass in a non-linear fashion (R2<0.2 as determined by linear regression).

Non-obvious but statistically significant differences were observed in the COV ranges covered by the four adduct types H+, Na+, NH4+ and water loss in positive mode (ANOVA, p<0.05). Significant COV differences were also observed between COVs of individual adducts derived from the same compound in paired t-Tests (data not shown). For example, M+H adducts tended to have lower COVs than the corresponding ammonium adducts, potentially due to the higher mobility of the smaller proton adducts in the DMS cell. To avoid confounding results originating from heterogeneous adduct formation, the following discussions are limited to single adduct types.

Correlations between compensation voltage and HPLC retention factors

We compared the DMS-derived COV optima with the HPLC retention factors for the same compounds, including both reversed-phase and HILIC methods [11]. A high correlation indicates high orthogonality of the two separation mechanisms. We postulate that the biggest benefit when looking to increase the peak capacity of a separation would come from coupling the DMS separation with an HPLC method that has a low correlation coefficient.

Based on 135 metabolites for which all relevant data were available, we discovered strong positive correlations between the positive-mode DMS behavior and RP-based retention (Table 1). Similar results were obtained for the negative mode DMS separation (183 metabolites). This finding is in agreement with previous studies, which suggested that the application of isopropanol as the modifier enhances contributions from hydrophobic (dispersive) interactions to the gas-phase mobility. It is conceivable that the similarities between RP-type retention and DMS behavior arise from the closely related, non-covalent interaction between the analyte and alkyl chains or modifier/solvent molecules, respectively, in RP and DMS environments. The well-known influence of ionic additives on RP-type retention might be mirrored in the DMS. Ionic additives could mask an analyte’s charge and enhance clustering with the modifier, thus leading to a larger reduction in low-field mobility and, consequently, more negative COVs compared to the free analyte.

Table 1.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients show the degree of orthogonality between HPLC (columns) and DMS separations (rows).

| RP | MM-RP | MM-HILIC | Amide | pHILIC™ | cHILIC™ | NH2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Positive mode | 0.527** | 0.520** | 0.146* | −0.175* | −0.017 | −0.213** | 0.052 |

|

| |||||||

| Negative mode | 0.436** | 0.343** | 0.162* | 0.073 | 0.041 | 0.002 | 0.06 |

|

|

|||||||

Data are presented for protonated (positive mode) and deprotonated adducts (negative mode) in DMS. HPLC columns (see [11]): RP, reversed phase. MM-RP, mixed-mode reversed phase. MM-HILIC, mixed-mode hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. pHILIC/cHILIC, zwitterionic HILIC. NH2, amine.

significant at 0.05 level.

significant at 0.01 level

This study did not involve systematic investigations of different additive types but the above-mentioned COV differences observed between different adducts of the same analyte (preceding section) seem to corroborate this hypothesis.

Weaker correlations indicating a higher degree of orthogonality were observed between DMS and zwitterionic HILIC methods. A sulfobetaine-based HILIC separation would be the most promising candidate for increasing HPLC peak capacity using DMS in either ionization mode. The question whether a negative correlation (e.g., phosphatidylcholine/positive mode DMS) indicates the opposite (detrimental effect of DMS separation on HPLC separation) will be investigated in an upcoming study.

Correlations between compensation voltage and molecular descriptors

We proceed to investigate the correlations of the measured COV optima with molecular descriptors accurate mass M, octanol/water distribution coefficient logP, acid/base dissociation constants pKa of the most acidic and most basic groups, the hydrophilicity logD. and the polarizability α. Probing these correlations for a large set of analytes will help understanding and, importantly, predicting the DMS processes contributing to the observed mobility. Recent research suggests that DMS data could be used to predict physical properties of drug candidates [16]. Table 2 summarizes Pearson’s correlation coefficients for individual descriptors in positive mode. Plots of COV vs. individual descriptors are shown in Fig. S2 (Supplementary Information).

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients indicate adduct-dependent influence of acid/base chemistry, hydrophobicity and polarizability on DMS behavior.

| Accurate Mass | pKa (most acidic) | pKa (most basic) | logP | logD (pH=3) | logD (pH=7) | Polarizability/Å3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [M+H]+ | Pearson Correlation | 0.691** | −0.132 | −0.301** | 0.208** | 0.213** | 0.057 | 0.705** |

| N | 242 | 201 | 165 | 226 | 225 | 225 | 210 | |

| [M+H−H2O]+ | Pearson Correlation | 0.255** | −0.002 | −0.192* | 0.169** | 0.180** | 0.102 | 0.228** |

| N | 299 | 260 | 151 | 279 | 277 | 277 | 264 | |

| [M+Na]+ | Pearson Correlation | .591** | −0.048 | −0.233** | 0.424** | 0.353** | 0.273** | 0.650** |

| N | 227 | 187 | 123 | 207 | 205 | 205 | 191 | |

| [M+NH4]+ | Pearson Correlation | 0.342** | 0.041 | −0.036 | 0.022 | −0.015 | −0.008 | 0.398** |

| N | 253 | 212 | 146 | 233 | 232 | 232 | 220 | |

| [M−H]− | Pearson Correlation | 0.683** | −0.040 | −0.088 | 0.312** | 0.233** | 0.195** | 0.730** |

| N | 366 | 337 | 190 | 355 | 353 | 353 | 309 |

Data are presented by adduct type.

significant at 0.05 level.

significant at 0.01 level

For positive mode data, statistically significant correlations with COV were found for α, M, pKa of the most basic group and logP, with correlation significance and coefficients differing between ion types. For example, proton and sodium adducts show a strong positive correlation of COV with polarizability, whereas this correlation is notably weaker in ammonium adducts. Regardless, the overall most significant correlations with observed COV were found for polarizability. This was true for both positive and negative mode. The observed, positive correlations mean that higher polarizability was associated with a COV closer to zero (the observed COV range was between −40V and 10 V).

Polarizability, which was found to correlate with the migration order of isomeric bile acids (see below), quantifies a molecule’s ability to respond to external electrical fields by forming instantaneous diploes through a displacement of electrons within the molecule. The higher the polarizability, the easier it is to induce the formation of a transient electric dipole by application of an electric field. It is not known if the SV would cause a greater deflection for an analyte with a tight electronic structure compared to a highly polarizable one. In the case of bile acids, the observed separation could also be the result of differences in ionization state or localization between the isomers.

3.2. Selectivity of the differential mobility spectrometry platform for chemically related metabolites

The next analysis level consisted of comparing the DMS behavior of chemically related compounds to elucidate which structural properties drive their separation. Only protonated and deprotonated species are discussed.

Lipids and related compounds

The DMS system has previously been shown to facilitate class separations of complex (phospho-)lipids [7,8] and a lipidomics platform based on DMS-MS/MS has been commercialized (international patent WO/2016/125120, via https://patentscope.wipo.int/search, accessed January 2018).

It is therefore not surprising that this highly hydrophobic metabolite class was successfully addressed by the DMS. This was especially true in negative mode, where 43 % of the lipids in the test set were detected (deprotonated molecules only).

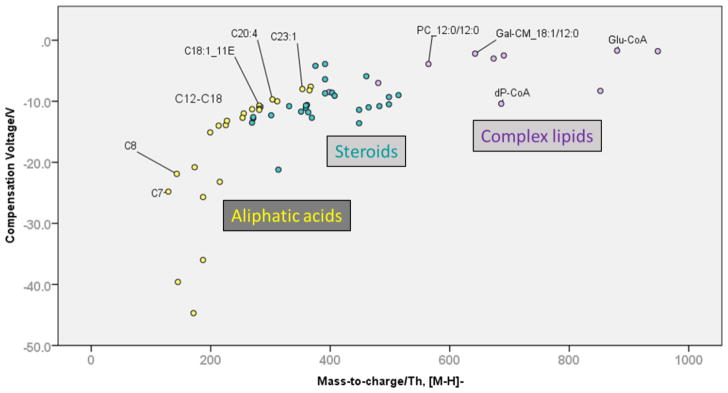

The hydrophobic compounds were assigned to three sub-classes for the data evaluation: aliphatic (fatty) acids, complex lipids including phospholipids, and steroids. As shown in Fig. 2, the three groups occupy different ranges of the separation space. Optimum COVs increased from aliphatic acids to steroids to complex lipids. A strong correlation was observed between negative mode COV and polarizability (R2=0.50).

Fig 2. Separation space distribution of aliphatic acids, steroids and complex lipids (deprotonated metabolites).

Fatty acids are denoted as C_[carbon number]:[double bond number]_[double bond configuration] where applicable. PC, phosphatidylcholine. Gal-CM, galactosyl-ceramide, dP-CoA, dephospho-Coenzyme A, Glu-CoA, glutamyl-Coenzyme A.

The COV ranges for the hydrophobic sub-groups were consistent in positive and negative mode (Fig. S3, Supplementary Material). This is not necessarily trivial, as lipid ionization depends on the head groups. This typically leads to certain classes being overrepresented in positive mode, whereas others are only accessible to analysis in negative mode. For example, phosphatidylcholines could be detected in positive as well as in negative mode. On the other hand, free fatty acids were only detected in negative mode.

Aliphatic acids were spread out over a larger COV range than the other two groups, with dicarboxylic acids exhibiting the overall lowest COVs. Generally, the COV increased with chain length. For fatty acids with carbon numbers 6–24, we determined that an additional methyl group was associated with a COV increase of 1.46 V (linear regression, p<0.001). Analogous to retention time in reversed-phase HPLC, a double bond or branching decreased the COV compared to the saturated and straight-chain compound, although this effect was not typically sufficient for baseline resolution by DMS.

Steroids and related compounds showed intermediate COVs in accordance with their large hydrophobic scaffold and relatively small, electronegative substituents. The complexity of the involved structures and non-obvious selectivity increments prevented us from establishing a universal rule for the migration order. For example, the keto-substituted steroid hormone estrone was not separated from its hydroxy-substituted analogs (α- and β-estradiol, 2-methoxy-estradiol) or from cortisone and its derivatives. On the other hand, the DMS successfully separated bile acids and showed chemical selectivity (esters vs. free acids) as well as isobar selectivity (see below). Whether selectivity is shape-driven (“bowl” shape of bile acids) or has a physical-chemical origin (substituent type and pattern) is unknown at this point but will hopefully be the subject of closer investigations in the future.

Complex (phospho-)lipids migrated at COVs close to zero in negative mode. Their migration order, LPE < PC < PA < DG, was consistent with reversed-phase HPLC separations and corresponds to the polarity of the head group [7]. Again, a correlation between carbon number and COV can be observed. However, due to the small number of phospholipids per class in the test set, the intra-class spread due to carbon number is not well reflected. Thus, definitive statements regarding the COV range of each class were not feasible.

The test set also included members of the acyl-CoA family. Comparing their COVs, we observed that the short-chain CoAs bearing malonyl and glutaryl residues were well separated. However, it was surprising that glutaryl-CoA co-migrated with long-chain lauroyl-CoA. This finding contradicts to some extent the notion that higher hydrophobicity corresponds to a higher COV, as was observed for aliphatic acids (see above). As an alternative explanation, Mal-CoA could be subject to enol formation on account of its highly acidic α hydrogen atoms. The other Acyl-CoAs are not as likely to undergo the same transformation as they lack this structural feature. This hypothetical enol formation might lead to Mal-CoA having different ionization properties than the other two, resulting in different COVs. Unfortunately, the low number of acyl-CoAs in the test set prevented further investigation of this aspect. Interestingly though, C3- and C12-acyl CoAs were barely separated from other acyl CoAs in positive mode, which probably indicates a shift in the gas-phase behavior of the protonated vs. deprotonated analytes.

Organic acids

Due to their acidic nature, only about 10 protonated, benzoic and phenylacetic acids were detected in positive mode and their migration order could not be rationalized. In negative mode, however, aromatic and aliphatic organic acids were divided into two distinct clusters (Fig. S4, Supplementary Material). Acids in the larger cluster (“A”) had a COV of < −10V, whereas the smaller cluster (“B”) consisted of acids with a COV between −10 V and 0 V. The aromatic acids in “B” were salicylate and mandelate as well as heterocyclic pyridoxate and orotate. Aliphatic acids in the same cluster included malate and long-chain fatty acids (see lipids). PCA of the available solute descriptors (polarizability, acid/base constants, logP, logD and m/z) did not yield a definitive answer as to the origin of this clustering pattern for either the aromatic acid or the aliphatic acid class. Neither did a reduced PCA using only polarizability, acid constant, logD@pH7 and m/z. It is possible that, again, tautomerism or different protonation sites play a role, as might the nature of the chemical modifier.

Previous publications have demonstrated that the COV of phospholipids becomes more negative with increasing polarity of the head group and less negative with increasing chain length [7]. As indicated above, the latter observation is replicated here in the increasing COV observed for aliphatic carboxylic acids. Their COV increases almost linearly with chain length (R2= 0.747, adjusted for COV and logP). Dicarboxylic acids follow the same trend but are shifted downfield towards more negative COVs, potentially due to enhanced cluster formation with the organic modifier.

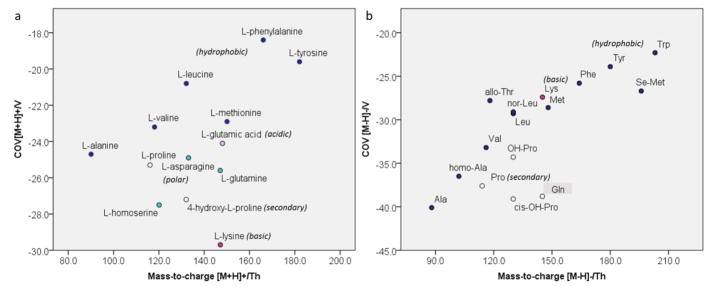

Amino acids

In positive mode, polar and charged protonated amino acids such as lysine (Lys) and hydroxyproline (OH-Pro) migrated at lower COV than their more hydrophobic counterparts (Fig. 3). Optimal COVs for non-polar, proteinogenic amino acids increased with increasing hydrophobicity of the side chain in the order of alanine (Ala) < valine (Val) ~ methionine (Met) < leucine (Leu) < tyrosine (Tyr) ~ phenylalanine (Phe). The hydrophobicity-driven migration order was even more pronounced in negative mode, where COVs increased continuously from Ala to Trp. Generally, COVs were shifted downfield in negative mode. This means that the deprotonated species required larger (more negative) COV to restore their trajectories, which could be related to relative size of protonated vs. deprotonated species. However, a connection to the relative ability to form clusters with isopropanol seems more likely.

Fig. 3. Distribution of proteinogenic amino acids across separation space.

a In positive mode, amino acids with hydrophobic side chains (blue dots) have higher compensation voltages than polar and ionic ones (purple and green dots). b In negative mode, compensation voltages increase with increasing hydrophobicity of the side chain.

Aminocarboxylic acids having polar side chains migrated at lower COVs than those with hydrophobic side chains. Looking at the entirety of the amino acids and derivatives in the test set, one can observe the emergence of low- and high hydrophobicity trend lines (Fig. S5, Supplementary Information).

In negative mode, N-derivatized species fell into the COV range between free, moderately to non-polar and highly hydrophobic amino acids (derivatives) such as triiodothyronine. The derivatives are both larger and more hydrophobic than their free analogs. Consequently, their mobilities are lower and the COVs required for their transmission are closer to zero. This effect seems less pronounced for hydrophobic amino acid derivatives (Boc-Leu, Boc-Phe) compared to charged ones such as N-methylated glutamic acid (N-Me-Glu).

Nucleobases

The DMS exhibited positive-mode selectivity towards nucleobases that seemed linked to the underlying heterocycle.

Free pyrimidine bases were not detected and the protonated pyrimidine nucleosides cytidine and deoxycytidine were not separated under our experimental conditions.

Purine bases and nucleotides, however, were among the isobars with the highest resolution observed in this study (see 3.3). The position of the substituent on the heterocyclic scaffold appeared to play a key role in these separations. We observed that the pyrimidine-substituted methylxanthines co-migrated with protonated guanine. Guanine also possesses pyrimidine substituents, namely an amino and a keto group, and lacks substituents on the imidazole ring. (It is worth noting that the methylxanthines are present in sodiated form, while guanine was detected as the proton adduct.) Together with hypoxanthine, which carries a hydroxyl substitutent, the nucleobases with amphoteric character were clearly separated from adenine, which completely lacks acidic functionalities. The resolution between of amino-substituted adenine and its hydroxyl analog hypoxanthine, was determined to be RDMS=1.58. Based on recent literature [17], it is likely that tautomerism contributes to the DMS behavior of nucleobases and their derivatives. Untangling the individual contributions from these factors was outside the scope of this study, even though we observed multiple peaks in some cases (see below).

Nucleosides

Protonated purine nucleosides were clearly separated into two groups by the DMS: The first group (COVs between −17 and −7 V) consisted of deoxyinosine (dI), 5′deoxyadenosine (5dA), 2′deoxyguanosine (dG), inosine (I) and guanosine (G). The second group (COVs between −28 and −25 V) consisted of 2′dexoyadenosine (2dA), adenosine (A) and 1-methyladenosine (Me-A). 5dA, whose main peak was assigned to the first group, showed a second peak comigrating with group 2. Clearly, the migration differences are related to the chemical nature of the pyridine modifications. All nucleosides in group 2 bear only nitrogen-containing substituents, whereas those in the first one (also) contain hydroxyl- and keto groups. Potentially, conformational preferences specific to each substitution pattern play a role in this clustering. The relative orientation of purine and sugar moiety can vary for each nucleotide (syn and anti conformations, anti is typically preferred). Both steric constraints and polar or hydrogen bond interactions might play a role in creating the mobility differences between the two groups. The two distinct peaks observed for 5′dA could be related to its lack of a primary hydroxyl group in position 5 of the sugar. The lower degree of steric hindrance could lead to higher ambiguity regarding the relative orientation of the nucleobase and sugar or the orientation of the glycosidic bond. The two peaks might correspond to two differently “shaped” conformational isomers of this analyte.

In negative mode, deprotonated dimethylurates migrated at a lower (more negative) COV than triple methylated caffeine, in accordance with their lower hydrophobicity. As mentioned earlier, hypoxanthine comigrated with dimethylurate. Its isobar theobromine, however, produced a double peak, likely due to tautomeric conversion.

Deprotonated purine nucleosides G and I migrated at slightly lower (more negative) COVs than their deoxy analogs. A, however, comigrated with both its methylated form (Me-A) and both deoxy species (2dA and 5dA). Overall, the keto groups of the guanosine and inosine derivatives caused these species to migrate at a lower COV than the adenine derivatives which lack this group. This reversal of the migration order compared to positive mode could be utilized to enhance specificity for critical separations.

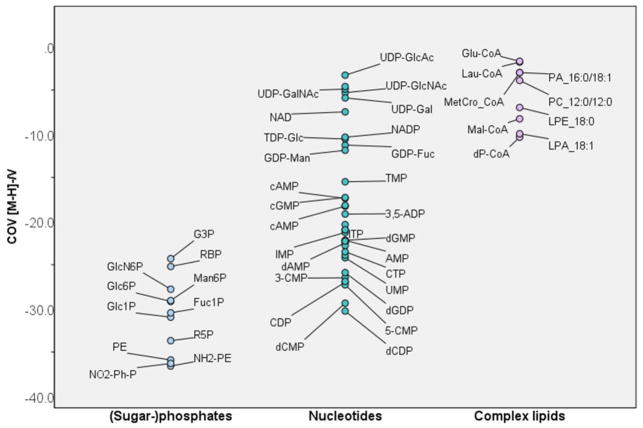

Phosphate-containing metabolites (nucleotides, sugar phosphates, complex lipids)

In negative mode, significant COV differences were observed between phospholipids, nucleotides and sugar phosphates. This result, shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. S6 (Supplementary Information), could be extremely useful for confirming metabolite IDs after assigning a molecular formula based on accurate mass.

Fig. 4. In negative mode, the compensation voltages for sugar phosphates are lower (more negative) than those of nucleotides and complex lipids.

Phosphates are annotated with abbreviations listed in Supplementary Information, Table S2.

In positive mode, we observed a trend towards higher (closer to zero) COVs with increasing m/z and increasing number of phosphate groups for nucleotides. Monophosphates occupied the COV space below −12 V, whereas di- and triphosphates migrated at COVs between −5 and −10 V. The determining factor in this separation seemed to be molecular size. Larger molecules are likely harder to divert from their initial trajectory and require less negative COVs to restore their path through the DMS cell. The higher degree of rotational freedom and the higher polarizability of di- and triphosphates might also be significant contributors to this result.

Interestingly, we did not observe selectivity for mono- vs. di- or triphosphonucleotides in negative mode. However, nucleotides derived from the same base were clustered together in a plot of m/z vs. COV (Fig. S6c). The median COVs increased in the order C < G < A < U (T). Linear regression suggested a strong correlation (adjusted R2=0.86) of the COV with molecular mass, pKa of the most acidic group, and hydrophilicity (logD for pH=3).

The negative ionization mode also facilitated the detection of several nucleotide sugars. These highly polar compounds migrated at COVs closer to zero than the respective nucleotides. In particular, nucleotide glucosamines were among the metabolites with the highest observed COVs (translating to lowest mobility) in this study. This result indicates a particularly high affinity to the modifier isopropanol.

Among the phosphorylated compounds, sugar phosphates exhibited the lowest (most negative) COVs. Isobaric glucose-1-phosphate (G1P) and glucose-6-phosphates (G6P) were not baseline separated but selectivity was slightly higher for this pair than for G6P vs. mannose-6-phosphate (M6P). This reflects the large influence that the conjugation site (glycosidic bond in position 1 vs. position 6) has on the overall molecular shape and, thus the mobility. Compared to this, the inversion of a stereocenter (glucose vs. mannose) has less of an effect on overall mobility.

Sugar phosphates migrated in a similar COV range as nucleotides, corroborating the notion that the highly polar, free phosphate group(s) play an important role in the DMS behavior of those compounds. For example, we observed that PA, a complex lipid with a free phosphate group, has a relatively low COV compared to other phospholipids. Note that it still migrates at a COV closer to zero than any nucleotides or sugar phosphates investigated in this studydue to its relatively high lipophilicity.

3.3. Selected separations of isomeric metabolites

After studying the test-set coverage and the behavior of chemically similar metabolites, we went on to identify successful separations of isomeric compounds achieved by the DMS. Separating isomers prior to MS detection is currently the most widespread application of the DMS in metabolomics. However, most studies are conducted in a targeted fashion and deal with optimizing separation conditions for a small number (typically 2–5) of metabolites. Here, we are using generic separation conditions to gain a better understanding of the range of isomer separations that can be achieved with a single method. In addition, we sought to identify structural features that facilitate successful isomer separations.

As a quantitative measure, the DMS resolution RDMS was defined as the distance between two peak maxima in units of average peak width w (Eq. 1).

| (Eq. 1) |

| (Eq. 2) |

Under the experimental conditions, baseline resolution (R>1) was achieved when the COVs of two isomers differed by at least 4 V. In positive mode, full separation of two isomers was observed in 7 out of 13 isomer groups. In negative mode, isomers were baseline resolved in 5 out of 10 isomer groups (Table T1, Supplementary information). Selected separations are summarized in Table 3 and discussed below. Corresponding ionograms are shown in Fig. S7.

Table 3. Selected isomer separations.

COV, compensation voltage, RDMS, resolution achieved by DMS, αHPLC, selectivity coefficient achieved by HPLC.

| Pair | Ionization | Adduct | COV (min)/V | COV (max)/V | RDMS* | αHPLC (column)** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aminohydroxybenzoates | + | [M+Na]+ | −21.1 | −9.3 | 2.95 | 5.53 (1) |

|

|

|||||||

| 2 | Methylxanthines | + | [M+Na]+ | −21.4 | −13.6 | 1.85 | 1.32 (1) |

|

|

|||||||

| 3 | Neurotransmitters | + | [M+H]+ | −28.2 | −16.8 | 2.85 | 1.99 (2) |

|

|

|||||||

| 4 | Phenolates | + | [M+Na]+ | −18.1 | −12.0 | 1.53 | 7.42 (1) |

|

|

|||||||

| 5 | Purine nucleosides | + | [M+H]+ | −27.8 | −14.9 | 3.45 | 1.66 (3) |

|

|

|||||||

| 6 | Dicarboxylates | − | [M−H]−, [M+Cl]− | −38.2 | −23.4 | 3.70 | 15.71 (2) |

|

|

|||||||

| 7 | Quinolinecarboxylates | − | [M−H]− | −30.8 | −26.9 | 0.98 | 3.45 (3) |

|

|

|||||||

| 8 | Bile acids | − | [M−H]− | −8.7 | −3.9 | 1.20 | 4.20 (4) |

Distance between maximum and minimum COV when 3 isomers were investigated (see text).

based on maximum and minimum retention factors from Ref. [11]. Columns: Amide (1), mixed-mode-HILIC (2), RP-C18 (3), amine (4).

We had detected multiple peaks for some purine derivatives, for example theobromine (see “nucleobases” in 3.2). Peak splitting of protonated nucleobases has been observed before and was attributed to the presence of multiple tautomeric forms of the same molecule [17]. However, the methylxanthines (MeX) investigated in this study produced single peaks and could therefore be regarded as present in only one tautomeric form. 3-MeX and 7-MeX co-migrated at a significantly lower (more negative) COV than 1-MeX. The MeX migration order corresponded to the position of the respective methyl groups on the purine scaffold: 3- and 7-MeX are both pyrimidine-substituted, while the methyl substituent in 1-MeX is located on the imidazole ring.

Another successful positive mode separation involved the isomeric purine nucleosides adenosine (A, COV=−27.8 V) and 2′-deoxyguanosine (dG, COV=−14.9 V). The corresponding resolution (RDMS=3.45) was among the highest observed in this study and could arise from conformational differences between the 2-hydroxylated nucleoside A and the dehydroxylated analog. As remarked upon earlier (3.2, “nucleosides”), it is likely that the two nucleosides prefer different relative orientations of carbohydrate and pyrimidine moiety. The resulting difference in molecular shape could cause differential clustering properties, mobility differences and, ultimately, isomer resolution.

2′-deoxyadenosine (2dA, COV=−26.3 V) and 5′-deoxyadenosine (5dA, COV=−11.3 V) were also separated with a high RDMS of 3.75. In this case, a second peak was observed for 5′-dA at −25 V. This suggested the presence of a second entity whose DMS behavior resembles that of 2′-dA. The absence of a primary hydroxyl group might allow 5′-dA to assume a conformation resembling the one preferred by 2′-dA. The syn orientation of pyrimidine and sugar, which is energetically unfavorable under standard conditions, could become more feasible inside the DMS cell. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the above mentioned 2′-dG produces a small secondary peak that co-migrates with adenosine. It is possible that the main peak of 2dG represents the the anti conformer (preferred due to steric hindrance of the methyl group), while the secondary peak indicates that the disfavored syn conformer is present at a much lower ratio.

Previous studies have shown that protonation at different sites can lead to multiple peaks for 4-aminobenzoic acid [18]. Based on this interesting phenomenon, we extracted MS traces for three aminohydroxybenzoic acids (AHBAs) with different substitution patterns (2,3-, 3,5-hydroxy- and 3,4-AHBA). Even though the acids were detected as sodium adducts rather than proton adducts, we observed small secondary peaks (below 15% of the height of the main peak) for all three investigated AHBAs in positive mode.

As they all showed one predominant peak, it was possible to determine isomer resolutions for AHBAs: 3,4-AHBA showed RDMS=2.20 and 2.95, respectively, from its two analogs. 2,3- and 3,5-AHBA were not fully baseline resolved from each other (RDMS=0.75). In this separation, the selectivity arises from the relative position of the substituents on the ring. 3,4-AHBA was the only para-substituted isomer. On the other two, substituents were located in ortho and meta positions relative to the carboxylic acid, which is likely to alter the ability to form clusters with isopropanol, and, consequently, lower the ion mobility in comparison to 3,4-AHBA. Another level of explanation might be offered by the protonation-deprotonation properties of the AHBA’s substituents. The acid/base chemistry of aromatic compounds is influenced by resonance stabilization and could cause AHBAs to become protonated at the hydroxyl group rather than the amine. As was shown by Campbell et al. in [18], the protonation of a carboxyl group can dramatically alter the COV of an aminobenzoic acid. It is reasonable to assume that such an effect also exists for the AHBAs, especially considering that secondary peaks were visible in their XICs.

Secondary peaks complicated the interpretation of data for many compounds. Examples included the phenolic acid derivatives 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (dopacetic acid, DPA), 2,5-dihydroxyphenylacetate (homogentisic acid, HGA) and 2-hydroxy-2-(3-hydroxyphenyl)acetic acid (m-hydroxymandelic acid, HMA). Catechol-derived DPA showed a single peak at −13.3 V, while the main peaks of HGA and HMA were shifted to lower and higher COVs, respectively. In addition, the XICs of the latter two showed additional, overlapping peaks with relative intensities of 95% and 25 % (HGA) and 26% (HMA) of the main peak. The second-highest peak of HGA co-migrated with HMA. We suspect that the overlapping peaks of HMA and HGA originate from the protonation of the m-hydroxyl groups. For HGA, the p- and m-OH groups are roughly equivalent, which might explain why this species shows only one peak. The lower-intensity peaks of HGA and DPA could be related to protonation of a secondary site, possibly supported by tautomeric conversion or resonance stabilization across the aromatic ring.

In negative ionization mode, we observed high selectivity for organic acids and lipids (see 3.2.). However, the resolution of 2- and 4-substituted quinolinecarboxylic acids was only 0.98 (no baseline separation). On the other hand, we observed an RDMS of 1.95 for medium-chain carboxylic acids 2-ethylhexanoic acid (EHA) and caprylic acid (CA). Both were detected as chlorine adducts. Even higher selectivity (RDMS=3.70) was observed for the dicarboxylic acids 3-methyladipic acid (MAA) and pimelic acid (PA). In both cases, one isomer was branched (EHA and MAA) and the second had a straight hydrocarbon chain (CA, PA). Clearly, the excellent resolution is a result of the substantial differences in molecular shape between the straight-chain and branched compounds. In both cases, the straight-chain species migrates at a higher (closer to zero) compensation voltage. This could indicate a lower tendency to form clusters with the modifier isopropanol and higher similarity of high- and low-field mobilities. It is also conceivable that the more extensive molecular shape of the straight-chain species decreases their gas phase mobility compared to the more compact branched analogs.

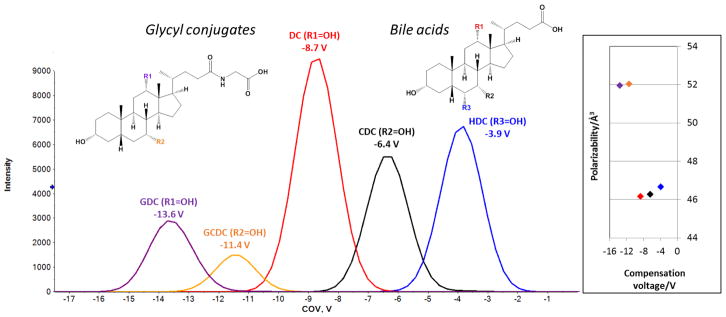

Finally, we investigated the migration order of isomeric bile acids differing only in the location of a single hydroxyl group on their steroid scaffold (Fig. 5a). We observed the migration order deoxycholate (DC) - chenodeoxycholate (CDC) – hyodoexycholate (HDC). In this separation, the COV is correlated to the predicted polarizability of the bile acids (black, red and blue traces in Fig. 5). In other words, the more polarizable bile acids exhibited higher (closer to zero) COVs. One interpretation of this result is that as the most polarizable of the three, HDC responds to the oscillating SV with internal electron displacement before its trajectory through the cell is affected. Less polarizable DC and CDC experience increased deflection from their original trajectory in response to the oscillating field (see also Section 3.1 Correlations between compensation voltage and molecular descriptors).

Fig. 5. The migration order of bile acids and their glycyl conjugates corresponds to their polarizability.

More polarizable compounds migrate at higher (closer to zero) compensation voltages than their less polarizable counterparts. For abbreviations, see text.

The migration order of glycyl conjugated deoxy- and chenodeoxycholic acid (GDC and GCDC) corroborated our hypothesis (purple and orange traces in Fig 5). The more polarizable GCDC migrated at higher COV than the less polarizable GDC. In this context, it is worth noting the considerable chemical selectivity of the DMS for the glycyl conjugates (average COV −12.50 V) versus the unconjugated bile acids (−6.33±2.40 V). Note also that the polarizability of the bile acids is lower than that of the conjugates. Nonetheless, the conjugates show significantly lower COVs, presumably due to increased modifier clustering driven by hydrophobic interactions. Alternative explanations of the observed migration order include the position of the charge on the bile acid (derivatives) and steric effects restricting clustering with the modifier.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

In this study, we aimed to investigate the application range and selectivity of a generic, isopropanol-based DMS separation for metabolomics. To this end, we determined the optimum COVs for over 500 metabolites in both ionization modes from a library containing 808 authentic standards. We found that the COVs were highly correlated with retention factors in RP-HPLC, which suggests that hydrophobic interactions, likely facilitated by ion pairing processes, could be involved in DMS separation HILIC-based HPLC appeared to be more orthogonal to the employed DMS technique and therefore appears promising for increasing the peak capacity in hyphenated separations.

As evident from the diversity of metabolites that were successfully detected after DMS separation in our study, the DMS-MS platform has an exceptionally broad application range. Our efforts to rationalize the observe separations of chemically related analytes such as lipids, amino acids and phosphate-containing molecules will help researchers to select promising application areas and target analytes for method optimization and HPLC-DMS-MS coupling. For example, the isomer separations of benzoic acid derivatives and nucleotides suggest that DMS might be a useful tool for studying drug metabolism or screening candidate biomarkers.

Future studies will need to focus on extending these observations towards application of the DMS platform in and beyond its current role in targeted metabolomics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by postdoctoral translational scholar program from the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research UL1TR000433 (to S.W.) and National Institutes of Health grants K08DK106523 (to F.A.), P30DK089503, DK082841, P30DK081943, U2C ES026553 and DK097153 (to S.P.).

References

- 1.Kanu AB, Dwivedi P, Tam M, Matz L, Hill HH. Ion mobility–mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2008;43(1):1–22. doi: 10.1002/jms.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell JL, Blanc JYL, Kibbey RG. Differential mobility spectrometry: a valuable technology for analyzing challenging biological samples. Bioanalysis. 2015;7(7):853–856. doi: 10.4155/bio.15.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider BB, Covey TR, Nazarov EG. DMS-MS separations with different transport gas modifiers. Int J Ion Mobil Spec. 2013;16(3):207–216. doi: 10.1007/s12127-013-0130-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray CJ, Thomas B, Upton R, Migas LG, Eyers CE, Barran PE, Flitsch SL. Applications of ion mobility mass spectrometry for high throughput, high resolution glycan analysis. Biochim Biophys Act. 2016;1860(8):1688–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofmann J, Hahm HS, Seeberger PH, Pagel K. Identification of carbohydrate anomers using ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Nature. 2015;526(7572):241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature15388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi Y, Nishima W, Re S, Sugita Y. Confident identification of isomeric N-glycan structures by combined ion mobility mass spectrometry and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2012;26(24):2877–2884. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lintonen TPI, Baker PRS, Suoniemi M, Ubhi BK, Koistinen KM, Duchoslav E, Campbell JL, Ekroos K. Differential Mobility Spectrometry-Driven Shotgun Lipidomics. Anal Chem. 2014;86(19):9662–9669. doi: 10.1021/ac5021744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker PRS, Armando AM, Campbell JL, Quehenberger O, Dennis EA. Three-dimensional enhanced lipidomics analysis combining UPLC, differential ion mobility spectrometry, and mass spectrometric separation strategies. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(11):2432–2442. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D051581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu C, Blanc JCYL, Shields JS, Janiszewski J, Ieritano CF, Ye GF, Hawes G, Scott Hopkins W, Larry Campbell J. Using differential mobility spectrometry to measure ion solvation: an examination of the roles of solvents and ionic structures in separating quinoline-based drugs. Analyst. 2015;140(20):6897–6903. doi: 10.1039/C5AN00842E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell JL, Le Blanc JCY. Using high-resolution quadrupole TOF technology in DMPK analyses. Bioanalysis. 2012;4(5):487–500. doi: 10.4155/bio.12.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopfgartner G, Varesio E. Metabolomics in Practice. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2013. Tandem Mass Spectrometry Hyphenated with HPLC and UHPLC for Targeted Metabolomics; pp. 21–37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen P-S, Chen S-H, Chen J-H, Haung W-Y, Liu H-T, Kong P-H, Yang OH-Y. Modifier-assisted differential mobility–tandem mass spectrometry method for detection and quantification of amphetamine-type stimulants in urine. Anal Chim Act. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beach DG. Differential Mobility Spectrometry for Improved Selectivity in Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Paralytic Shellfish Toxins. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2017;28(8):1518–1530. doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wernisch S, Pennathur S. Evaluation of coverage, retention patterns, and selectivity of seven liquid chromatographic methods for metabolomics. Anal and Bioanal Chem. 2016;408(22):6079–6091. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9716-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wishart DS, Jewison T, Guo AC, Wilson M, Knox C, Liu Y, Djoumbou Y, Mandal R, Aziat F, Dong E, Bouatra S, Sinelnikov I, Arndt D, Xia J, Liu P, Yallou F, Bjorndahl T, Perez-Pineiro R, Eisner R, Allen F, Neveu V, Greiner R, Scalbert A. HMDB 3.0—The Human Metabolome Database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D801–D807. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C, Le Blanc JCY, Schneider BB, Shields J, Federico JJ, Zhang H, Stroh JG, Kauffman GW, Kung DW, Ieritano C, Shepherdson E, Verbuyst M, Melo L, Hasan M, Naser D, Janiszewski JS, Hopkins WS, Campbell JL. Assessing Physicochemical Properties of Drug Molecules via Microsolvation Measurements with Differential Mobility Spectrometry. ACS Central Science. 2017;3(2):101–109. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anwar A, Psutka J, Walker SWC, Dieckmann T, Janizewski JS, Larry Campbell J, Scott Hopkins W. Separating and probing tautomers of protonated nucleobases using differential mobility spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2017 doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2017.08.008.

- 18.Campbell JL, Le Blanc JCY, Schneider BB. Probing Electrospray Ionization Dynamics Using Differential Mobility Spectrometry: The Curious Case of 4-Aminobenzoic Acid. Anal Chem. 2012;84(18):7857–7864. doi: 10.1021/ac301529w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.