Abstract

Background

A multidrug treatment titrated to proteinuria by maximum tolerated doses of an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) combined with intensified blood pressure (BP) control prevented renal function loss in adults with proteinuric nephropathies. Herein, we investigated the effects of this program in children.

Methods

From May 2002 to September 2014 we included in this observational, longitudinal, cohort study twenty consecutive children with chronic nephropathies and 24-h proteinuria >200mg who received ramipril and losartan up-titrated to maximum approved doses (2.48±1.37 mg/m2 and0.61±0.46 mg/kg daily, respectively). The primary efficacy endpoint was more than 50% 24-h proteinuria reduction to <200 mg (Remission). Secondary outcomes included changes in proteinuria, serum albumin, BP, and glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

Results

Mean (±SD) patient age at inclusion was 13.8±2.8 years, median (IQR) serum creatinine 0.7 (0.6-1.0) mg/dl and proteinuria 690 (379-1270) mg/24h [or 435 (252-711) mg/m2/24h]. Proteinuria significantly decreased by month six and serum albumin levels increased over a follow-up period of 78 (39-105) months. In the nine children who achieved remission, proteinuria reduction persisted throughout the whole follow-up without rebounds. GFR improved in the children with remission and worsened in those without. Mean±SD GFR slopes (+0.023±0.15 vs. -0.014±0.23 ml/min/1.73m2/month, respectively) significantly (p<0.05) differed, whereas BP control was similar between the two groups. We observed hyperkalemia in two children.

Conclusions

Combination therapy with maximum approved doses of ACE inhibitors and ARBs may achieve proteinuria remission with kidney function stabilization or even improvement in a substantial proportion of children with proteinuric nephropathies, and is safe.

Keywords: ACE inhibitor, Angiotensin receptor blocker, Children, Chronic nephropathy, Proteinuria

Introduction

Most adults and children with chronic kidney disease (CKD) tend to progress to end stage kidney disease (ESKD). Hypertension and proteinuria are the two major causes of progressive renal damage and function loss [1]. In particular, experimental and human data converge to indicate that there is a continuous relationship, without thresholds, between proteinuria [2], including residual proteinuria while on angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibition therapy [3], and renal disease progression. Moreover, proteinuria reduction, independently of treatment, is renoprotective in adults [4] as well as in children [5], and may even result in regression of renal lesions [6] and regeneration of kidney vasculature [7]. Effective blood-pressure (BP) reduction slows CKD progression in adults [8] and, among different antihypertensive agents, those that inhibit the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system (RAAS) - that is, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor-blockers (ARBs) - are the most renoprotective owing to their specific antiproteinuric effect [9-11].

According to the United States Renal Data System 2015 Annual Data Report (accessed on 30 June 2016 at: https://www.usrds.org/adr.aspx.), children account for 1.5% of the whole population with ESKD. While on chronic renal replacement therapy, the mortality of these children is approximately 30 folds higher than in their healthier peers [12]. Small studies reported a decrease in proteinuria and a slowing of renal function loss with ACE-inhibitor or ARB therapy in children with CKD [13-15]. A larger randomized study showed that both losartan and enalapril decreased proteinuria in 268 children with normal or high blood pressure [16]. The ESCAPE trial [17] found that 5-year intensified BP control in 385 children with CKD who received a fixed dose of an ACE inhibitor, delayed the time to 50 percent reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) or progression to ESKD more effectively than conventional BP control. Proteinuria decreased by more than 50 percent during the firs six months, but, unexpectedly, gradually increased thereafter towards baseline values despite good BP control in both treatment groups. According to the Authors [17], this rebound was most likely explained by a progressive activation of enzymes other than ACE, such as chymases, resulting in increased angiotensin-II production and secondary enhanced adrenal aldosterone release and aldosterone “escape” [18]. Since proteinuria plays a central role in the progression of CKD [19], this rebound might limit the long-term renoprotective effect of ACE inhibitor therapy [20].

Since ARBs block the activity of the angiotensin-II produced also through non-ACE pathways, add-on ARB treatment may theoretically prevent angiotensin-II-mediated aldosterone breakthrough and rebound proteinuria in patients on ACE inhibitor therapy. Consistently, combination therapy with ACE inhibitors and ARBs reduced proteinuria more effectively than ACE inhibitor monotherapy in adults with CKD [21], in particular when treatment was titrated to urinary proteins [22]. The Remission Clinic program, a multidrug treatment titrated to urinary proteins by maximum tolerated doses of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB combined with intensified BP control, significantly slowed renal function loss and reduced the risk for terminal kidney failure by 8.5 fold in 56 adults with proteinuric nephropathies as compared to matched-controls treated with an ACE inhibitor titrated to BP [23]. This proof of concept study intentionally included patients at high risk of accelerated renal function loss because of heavy proteinuria. A subsequent study, however, found that the Remission Clinic program was renoprotective also in adult patients with Alport Syndrome and micro- or macro- albuminuria [24]. On the basis of the above findings, this multidrug intervention was extended to all patients with CKD and urinary protein excretion >0.5 g/24 hours ([25]; accessed on June 6, 2016: http://clinicalweb.marionegri.it/international-remission/remission.php). Then, in order to assess whether this therapeutic option could be offered also to children at increased risk of progression to ESKD because of proteinuric CKD, we investigated the benefits, risks and feasibility of the Remission Clinic program in patients less than 18-year-old who had proteinuria persistently exceeding 200 mg per day and were monitored and treated in the context of a Pediatric Nephrology outpatient clinic.

Materials and Methods

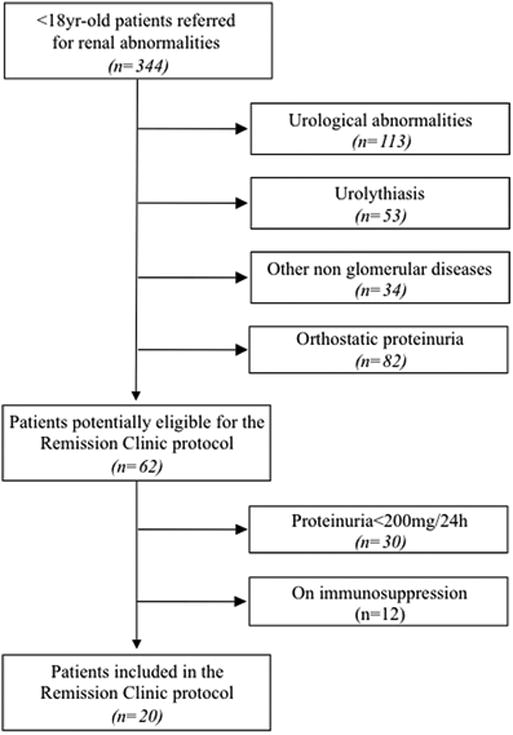

This longitudinal, observational, cohort study included all consecutive subjects less than 18 year-old referred to the Pediatric Nephrology Outpatient Remission Clinic of the Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII of Bergamo (Italy) who had 24-h proteinuria >200 mg for at least six months and no specific indication for immunosuppressive therapy nor contraindications to RAS inhibitor therapy. Children with ortostatic proteinuria or urological abnormalities including Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract (CAKUT) were excluded (Figure 1). Legal tutors provided written informed consent to data registration and use with preservation of children's anonymity and privacy. Data were recorded and reported according to the “Strengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)” guidelines for reporting observational studies (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Patients enrolled in the study.

Children were recommended to avoid salt-rich foods, but no specific restriction to dietary protein intake was enforced. At baseline, we recorded history, anthropometric values and clinical and laboratory data, including BP, proteinuria and estimated GFR (eGFR). Then children entered a pre-defined, standardized Remission Clinic protocol [23] that included treatment with an ACE inhibitor and an ARB, with other antihypertensive agents that were progressively titrated to 24-h proteinuria <200 mg (remission, primary endpoint). Children were started on a low (1.5 mg/m2) daily dose of ramipril that was progressively titrated up to a maximum dose of 5 mg/m2. If remission was not achieved, losartan was added at the starting daily dose of 0.35 mg/kg that could be titrated up to 1.4 mg/kg. No child received doses of ramipril or losartan above the reported limits. Timing for dose escalation (or reduction) was response-driven and individually tailored. Thus, each treatment step had to be implemented until remission was achieved or the protocol had to be stopped because of safety or tolerability reasons. More specifically, whenever treatment up-titration was associated with symptomatic hypotension, serum potassium increases to 5.5 mEq/L or more despite concomitant diuretic therapy and correction of metabolic acidosis, or serum creatinine increased by 25% or more versus baseline, the dose of ramipril and/or losartan was down-titrated until full recovery of any clinical or laboratory abnormality was achieved. If the abnormalities persisted, losartan (first) and ramipril were withdrawn, but the patient was maintained on active follow-up. Treatment could also be transiently back-titrated or withdrawn in case of intercurrent disorders such as vomiting and diarrhea. At any time, a diuretic (1 mg/kg/day of hydrochlorothiazide or 0.5 mg/kg/twice daily of furosemide if the GFR was above or below 40 ml/min/1.73 m2 respectively) was added and up-titrated to control edema or hyperkalemia and maximize the antiproteinuric effect of RAAS inhibition (Figure S1). Study parameters were recorded in an ad hoc database. BP was the mean of three values taken 2 minutes apart by a standard sphygmomanometer. Throughout the whole study period serum creatinine was always measured by the same enzymatic assay [26], a reference method that does not require standardization, and the GFR was estimated by 2009 revised Schwartz formula [27] in all study children. Percentiles and Standard deviation score based on the fourth report on Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents (accessed on June 5, 2016 at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/resources/heart/hbp_ped.pdf) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Growth Reference Year 2000 [28] were used to evaluate BP and to assess anthropometric measures to help evaluate children's growth, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

The primary endpoint was 24-h proteinuria reduction to <200mg with >50% reduction over baseline. Secondary outcomes included changes in proteinuria, serum albumin, BP, and eGFR. Primary outcome was analyzed on a time-to-event basis by means of Cox proportional-hazard survival analysis to assess the effects of potential risk factors.

The occurrence of missing follow-up data on 24-h proteinuria, eGFR, systolic and diastolic BP, serum potassium levels and hemoglobin concentration was addressed by multiple imputation using multi-level random-effects models on repeated measurements [29]. We generated ten Multiple Imputed datasets based on the linear mixed effects models of the longitudinal variable, including the baseline and time-visit and the median value of the imputed estimates over the time-visit were considered. Longitudinal changes in proteinuria were evaluated with the use of repeated-measure analysis. The linear mixed effects models of 24-h proteinuria (log transformed) included baseline 24-h proteinuria and time-visit and were adjusted for eGFR or systolic or diastolic BP standard deviation scores or gender, to test the robustness of the results. Sensitivity analyses were performed by evaluating the outcome 24-h proteinuria adjusted for body surface area (BSA). The BSA was calculated by the DuBois formula [30]. eGFR slopes (ΔeGFR) were estimated performing linear mixed effects models (by month 3) including the baseline eGFR, binary primary endpoint and time-visit. Groups were compared by using paired T test, Wilcoxon signed-ranks test, ANCOVA or quantile regression, as appropriate. Normality for continuous variables was assessed by means of the Q-Q plot. The data of baseline characteristics were presented as numbers and percentages, means and SDs, or medians and IQRs, as appropriate. All p values were two-sided. The analyses were performed by using SAS (version 9.1) and Stata (version 13) and REALCOM for the missing imputation.

Sample size estimation

Because of the observational nature of the present study, the sample size was not calculated a priori on the basis of a predefined treatment effect. However, on the basis of previous evidence in adult patients with non-diabetic proteinuric CKD [23] we expected that a study of 20 children would be able to detect the antiproteinuric effect of the Remission Clinic program in this context.

Results

Twenty children, ten males, who fulfilled the selection criteria for the Remission Clinic protocol were identified among the 344 patients referred to our Pediatric Nephropathy outpatient clinic (Figure 1). They were included from May 2002 to September 2014 and followed-up to May 2015. At inclusion all of them were proteinuric, with normal or moderately reduced kidney function and BP values in recommended target. Mean (±SD) patient age at inclusion was 13.8±2.8 years, median (IQR) serum creatinine levels and proteinuria were 0.7 (0.6-1.0) mg/dl and 690 (379-1270) mg/24h and 435 (252-711) mg/m2/24h. Mean (±SD) systolic and diastolic blood pressure were 108.2±14.6 mmHg and 64.4±9.4 mmHg, with Standard deviation score of -0.22±1.21 and 0.17±0.84, respectively. Sixteen children had a biopsy proven chronic glomerular disease (Table 1). One child had a history of shigatoxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) without identification of genetic abnormalities predisposing to the disease, and a second one of atypical HUS with a heterozygous mutation in factor H gene. None of them had any evidence of active microangiopathy or was on ongoing treatment with plasma or complement inhibitors at the time of inclusion.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the study group as a whole (Overall) and according to the remission status (Remission YES or Remission NO), considered separately.

| Characteristics | Overall (n=20) |

Remission Yes (n=9) |

Remission No (n=11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 13.84±2.78 | 13.10±2.60 | 14.43±2.89 |

| Male gender (n %) | 10 (50.0%) | 6 (66.7%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| Underlying renal disorder (n %) | |||

| IgA nephropathy | 7 (35.0%) | 4 (44.4%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| Alport syndrome | 3 (15.0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| HUS | 2 (10.0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| FSGS | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Vacterl Syndrome | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| CKD from neonatal sepsis | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| ARPKD with hepatic fibrosis | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unknown* | 4 (20.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 108.2±14.6 | 107.2±19.6 | 108.9±9.8 |

| SD score | -0.22± 1.21 | -0.18± 1.32 | -0.26± 1.18 |

| >95th percentile (n %) | 2 (10%) | 1 (9%) | 1 (11%) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 64.4±9.4 | 63.9±12.0 | 64.8±7.2 |

| SD score | 0.17±0.84 | 0.05±0.96 | -0.01±0.78 |

| >95th percentile (n %) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.70 (0.58-0.97) | 0.69 (0.54-1.00) | 0.80 (0.58-0.94) |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 4.04±0.43 | 4.17±0.48 | 3.94±0.38 |

| Proteinuria (mg/24h) | 690 (379-1270) | 460 (270-890) | 700 (540-2000) |

| Proteinuria/BSA (mg/m2/24h) | 435 (252-711) | 436 (205-595) | 433 (308-1182) |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 90.7±26.5 | 87.2±28.7 | 93.3±27.0 |

Variables are expressed as mean ± SD, median (IQR), absolute number or percentage. ARPKD: Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease; FSGS: Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis; HUS: Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome; BSA: Body Surface Area.

In 3 cases kidney biopsy was not informative due to limited material. No difference in any considered variable between Remission Yes and Remission No was statistically significant.

Main Outcomes

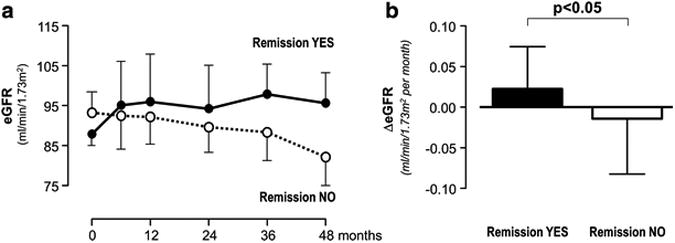

Over a median (IQR) follow-up of 78 (39-105) months, nine children achieved remission of proteinuria. The endpoint was reached at 11.6 (10.8-14.1) months after inclusion. Baseline characteristics of children with or without remission were similar (Table 1). Remission was predicted by lower baseline proteinuria at univariable analysis and by male gender and lower proteinuria at multivariable analyses (Table 2). The outcome of children with VACTERL syndrome, neonatal sepsis, Autosomal Recessive, Polycystic Kidney Disease (ARPKD) or CKD from unknown causes was similar to the outcome of the other study children, and no association was observed between underlying etiology and progression to remission. Estimated GFR tended to increase in patients who achieved remission and to decrease in those who did not (Figure 2, Panel A). The mean eGFR slope was positive in children with remission and negative in those without, and significantly differed between the two groups (+0.023±0.15 vs. -0.014±0.23 ml/min/1.73m2/month, p<0.05; Figure 2, Panel B).

Table 2. Univariable and multivariable Cox analysis showing the association between baseline factors and the outcome remission.

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age (y) | 0.85 (0.67 - 1.10) | 0.215 | ||

| Male Gender (n %) | 2.65 (0.66 - 10.67) | 0.169 | 13.51 (1.92 - 95.09) | 0.009 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 0.99 (0.97 – 1.02) | 0.509 | ||

| Proteinuria (mg/24h)* | 0.30 (0.11 - 0.84) | 0.022 | 0.10 (0.02 - 0.45) | 0.002 |

| Proteinuria/BSA (mg/m2/24h)* | 0.35 (0.13 - 0.98) | 0.045 | ||

| SBP - Standard deviation score | 1.06 (0.59 - 1.89) | 0.85 | ||

| DBP - Standard deviation score | 0.97 (0.41 - 2.29) | 0.951 | ||

log transformed. SBP= systolic blood pressure; DBP= diastolic blood pressure; eGFR= estimated glomerular filtration rate; BSA= body surface area

Figure 2.

Course of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR, Panel A) and changes in eGFR over time (ΔeGFR, Panel B) in the two subgroups achieving (Remission YES) or not achieving (Remission NO) remission of proteinuria considered separately. Data are mean ±SEM.

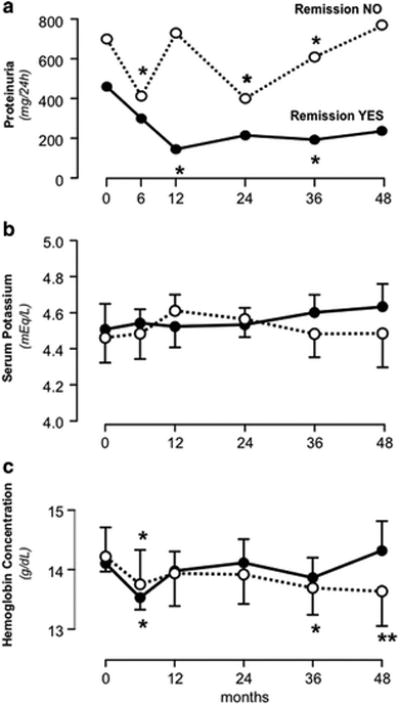

Overall, proteinuria significantly decreased at six months and was persistently lower than at baseline throughout the whole observation period. The reduction was larger in patients who achieved remission than in those who did not, and in those with remission it persisted throughout the whole follow up without rebounds (Figure 3, Panel A). Linear mixed effects models showed that proteinuria reduction was significant (Coefficient (95% CI):-0.010 (-0.016 to -0.004), p<0.001) and retained its significance even after adjustment for gender, eGFR, and systolic or diastolic BP standard deviation score (Table S2). Similar findings were obtained when statistical analyses considered proteinuria normalized by BSA (Table S3).

Figure 3.

Course of 24-hour urinary protein excretion (Panel A), serum potassium (Panel B) and hemoglobin concentrations (Panel C) in the two subgroups achieving (Remission YES) or not achieving (Remission NO) remission of proteinuria considered separately. Data are mean ±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. baseline (time 0).

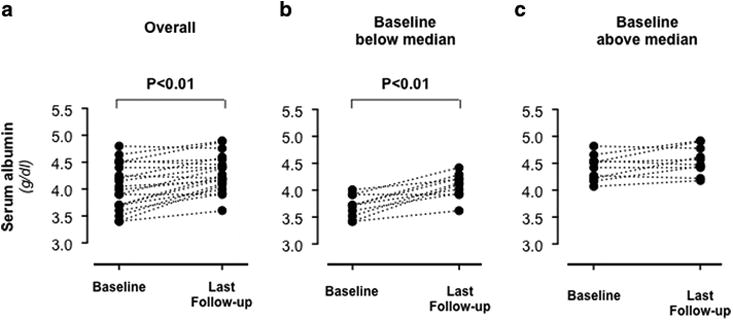

Proteinuria reduction was associated with a significant (p<0.01) serum albumin increase from 4.04±0.43 at inclusion to 4.30±0.34 g/dl at last available follow up visit (Figure 4) that was largely driven by increases (from 3.68±0.21 to 4.01±0.24 g/dl, p<0.01) in children with albumin levels below the median at inclusion (Figure 4, Panel B and C).

Figure 4.

Single patient serum albumin levels at baseline and at last available follow-up visit in the study group considered as a whole (Panel A) and in the two subgroups with baseline serum levels below (Panel B) or above (Panel C) the median.

Treatment and Blood Pressure Control

At study end, 12 participants were on ACE inhibitor and ARB combination therapy and eight on ACE inhibitor monotherapy. Six could not be maintained on combination therapy because of hypotension and two because of hyperkalemia (Table 3). Final doses of ramipril and losartan averaged 2.48 ± 1.37 mg/m2 and 0.61 ± 0.46 mg/Kg daily, respectively. BP was persistently in target and did not differ between patients who achieved or did not achieve remission during the observation period (data not shown).

Table 3. Serious and non serious adverse events in the study group considered as a whole (Overall) and according to Remission Status (Remission YES vs Remission NO).

| Event | Overall (n=20) |

Remission YES (n=9) |

Remission NO (n=11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | 16 | 5 | 11 |

| Any serious adverse event | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Pyelonephritis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Appendicitis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Any non serious adverse event | 13 | 5 | 8 |

| Requiring treatment back titration | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Persistent symptomatic hypotension | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Refractory hyperkalemia | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Not requiring treatment back titration | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Hypoacusia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Erythema nodosum | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Transient transaminase increase | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mononucleosis | 1 | 1 | 0 |

One patient in the Remission No group temporarily withdrew therapy because of pregnancy.

Safety

Serum potassium levels and hemoglobin concentration were relatively stable on follow-up. No appreciable differences in serum potassium levels were observed between children with or without remission (Figure 3, Panel B). In both groups hemoglobin concentration significantly decreased at month six as compared to baseline. Thereafter, it progressively increased in children who achieved remission, whereas it was persistently lower as compared to baseline in those who did not (Figure 3, Panel C).

Overall, adverse events were more frequent in children who did not achieve than in those who achieved remission. Three infectious events that were considered serious were observed in children without remission (Table 3). No patient had acute renal function deterioration, severe refractory hyperkalemia, anemia or any other serious adverse event possibly related to treatment. Eight non-serious events prevented up titration to dual RAAS blockade or required back-titration from dual RAS blockade to ACE inhibitor monotherapy. They included six cases of symptomatic hypotension and two cases of persistent hyperkalemia that were equally distributed among children with or without remission (Table 3).

Discussion

In this longitudinal, observational study, intensified BP control with a Remission Clinic treatment regimen titrated to urinary proteins by maximum approved doses of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB, achieved complete remission of proteinuria in nine out of twenty children with chronic renal parenchymal disease. Consistently with previous evidence in adults, proteinuria reduction translated into significant protection against renal function loss and amelioration of hypoalbuminemia. In children achieving remission, the reduction was sustained over time and no rebound proteinuria was observed over a median follow-up period exceeding six years. Lower proteinuria at inclusion and male gender predicted a higher probability of remission, whereas the outcome was not associated with underlying etiology and blood pressure control that was in recommended target in all children. Treatment was well tolerated and no child had to stop the program because of acute renal function deterioration, severe, refractory hyperkalemia or anemia. Actually, in subjects achieving remission the progressive improvement in kidney function was associated with a parallel increase in hemoglobin concentration.

Thus, previous evidence that the Remission Clinic protocol may achieve persistent remission of proteinuria and halt renal disease progression in approximately 50 percent of adults with proteinuric chronic nephropathies [23], can be extended to children with proteinuric CKD. Finding that remission of proteinuria prevented renal function loss over time provided convincing evidence that, independently of blood pressure control, residual proteinuria, even in the sub-nephrotic range [3], is a major risk factor for renal disease progression also in children. This finding may have clinical implications since sustained reduction in proteinuria is expected to translate into effective protection against progression to ESKD [3]. The concomitant amelioration of hypoalbuminemia might also be beneficial.

Notably, persistent remission of proteinuria could not be achieved in the ESCAPE trial despite good blood pressure control [17]. Within the limitations of comparative analyses between different studies that included patients with different characteristics, these findings suggest that, unlike single drug blockade of the RAAS with a fixed dose of an ACE inhibitor [17], combination therapy with an ARB may possibly prevent aldosterone “escape” [18] and proteinuria rebound. Since proteinuria plays a central role in the progression of CKD [19], prevention of this rebound by a treatment titrated to urinary proteins might be instrumental to maximize the long-term renoprotective effect of RAAS inhibitor therapy also in children with proteinuric chronic nephropathies [20]. On this regard it is interesting to note that the Supra Maximal Atacand Renal Trial (SMART) found that supramaximal dosages of candesartan lead to greater reductions of proteinuria compared with the highest approved antihypertensive dosage of candesartan (16 mg/d) in patients with primary glomerular diseases, diabetes, or hypertensive glomerulosclerosis and persistent proteinuria ≥1 g/d, despite treatment with approved doses of candesartan [31]. These data confirmed that intensified RAAS inhibition is an effective approach to reduce proteinuria in patients with CKD. However, high-dose ACE inhibitors are at least as effective as high-dose ARBs and are less expensive [32].. Thus, the cost/effectiveness of ARB up-titration to maximum tolerated doses is questionable at least. Moreover, in patients with non-diabetic CKD ACE inhibitor and ARB combination therapy reduced proteinuria more effectively than each agent alone, even at high doses (reviewed in [33]). Thus, as previously reported in adults [23, 24], dual RAAS blockade appears to be the most efficient approach to reduce proteinuria in non-diabetic patients with CKD.

In our present study, proteinuria decreased by an effect that appeared to be largely independent of blood pressure control and blood pressure was similar in children who achieved or did not achieve remission. Finding that the proportion of children on ACE inhibitor monotherapy was small and similar in the two groups, suggests that failure to achieve remission was unlikely explained by ineffective RAAS inhibition. Thus intrinsic, possibly genetically determined mechanisms [34], may explain different individual response to the same treatment protocol.

The etiology of renal disease in our study patients was heterogeneous. However, they shared a unifying characteristic: all of them were at risk of progressive renal function loss because of a common pathogenic pathway mediated by protein traffic [1]. Consistently, the Remission Clinic approach, a multidrug intervention designed to specifically target this common target by maximized RAAS inhibition, achieved remission of proteinuria independently of the underlying renal disease. Finding that the blood pressure was already in recommended target at inclusion and did not change appreciably throughout the whole observation period can be taken to suggest that the reduction in proteinuria we achieved with the Remission Clinic approach can be reasonably attributed to more effective RAAS inhibition rather than to improved blood pressure control.

Safety

Pediatric patients are a fragile population and the potential risks of ACE inhibitor and ARB combination therapy must be carefully evaluated in this context, in particular in children with more advanced CKD. Independently of this general consideration, however, the results of trials such as the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET), which questioned the risk/benefit profile of dual RAAS blockade in adults with cardiovascular disease but no evidence of overt proteinuric nephropathy [35], should not be generalized to the average population of patients (including children) with proteinuric kidney disease [36]. Indeed ONTARGET showed that Ramipril plus Telmisartan combination therapy prevents microalbuminuria but facilitates transient renal function impairment in non-proteinuric patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease or diabetes. However, only a very small proportion of ONTARGET patients was proteinuric, whereas most of them were at high risk of ischemic kidney disease and other clinical conditions predisposing to acute renal function deterioration and/or hyperkalemia in case of dehydration from any cause, or intercurrent events such as sepsis, acute myocardial infarction with heart failure, bleeding, major trauma or surgery. Thus, these patients had no cogent indication to dual RAAS blockade and were at the same time at excess risk of complications related to unnecessarily maximized inhibition of the RAAS. This does not apply to children under evaluation here since all of them were proteinuric and none of them had atherosclerotic vascular disease. Two other studies, the VA NEPHRON D [37] and the ALTITUDE [38] trials, found that dual RAAS blockade with an ACE inhibitor [37] or a renin inhibitor [38] added-on ARB therapy failed to improve nephroprotection as compared to ARB monotherapy in type 2 diabetics with nephropathy and associated with more side effects. Both studies were stopped prematurely for safety and futility reasons, leading regulatory authorities such as the European Medicines Agency's Committee for Medical Products for Human Use (CHMP) to endorse restrictions for dual RAAS inhibition therapy in patients with diabetes or moderate to severe renal impairment (GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2) (http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Press_release/2014/05/WC500167421.pdf). When the VA NEPHRON D study closed, dual RAAS inhibition had already reduced ESKD events by 34% compared with ARB monotherapy, a treatment effect never achieved before in type 2 diabetes which approximated nominal significance (p = 0.07) over just 2.2 years of follow-up. Conceivably, the opportunity to demonstrate clinically relevant nephroprotection over the planned five-year follow-up was missed because of premature study closure dictated by adverse events, such as hypotension, hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury, which could have been prevented by avoiding up-titration of lisinopril (up to 40 mg daily in patients with an estimated GFR as low as 30 ml/min/1.73 m2) on top of full-dose losartan. The excess risk of adverse events observed with dual RAS blockade was therefore largely explained by treatment-related and potentially reversible hemodynamic effects which could be expected since type 2 diabetics with overt nephropathy are in most cases older patients who, similarly to ONTARGET patients, are at increased risk of ischemic kidney disease or nephroangiosclerosis. Independently of these considerations, none of our children were diabetic. This may explain why in our pediatric population the Remission Clinic protocol effectively reduced proteinuria and was safe and well tolerated as previously observed in adults with non-diabetic proteinuric CKD [23]. Thus, we fully agree with the EMA recommendation that in cases where combined use of an ARB and ACE inhibitor is considered absolutely essential– such as in adults and children with non-diabetic proteinuric CKD –, “it must be carried out under specialist supervision with close monitoring of renal function, electrolytes and blood pressure”. Whether this approach can be safely extended to children with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 is worth investigating.

Limitations and Strengths

The lack of a parallel control group and the small sample size were conditional to the rarity of the disease entity under evaluation here. We included only children without evidence of urogenital abnormalities to avoid the risk that factors other than proteinuria and BP control – such as obstruction, vesicoureteral reflux, intercurrent urinary tract infections or chronic nephrolithiasis – could affect considered outcomes and therefore confound data interpretation. Thus, our present findings specifically apply to children with proteinuria and chronic renal parenchymal disease who share a common pathogenic pathway mediated by protein traffic [1]. Consistently, treatment effect was similar between the seven patients with VACTERL Syndrome, previous sepsis, ARPKD or unknown disease and the rest of the cohort.

The long follow-up is a strength and the conduction of the study in the context of an outpatient clinic allows data generalizability to the average population of children referred to pediatricians or nephrologists in every day clinical practice. Avoidance of fixed, pre-defined standard doses and the use of a flexible treatment protocol that could be modulated according to patient response, in combination with close clinical monitoring, most likely explained why treatment was effective in reducing proteinuria and at the same time was safe and well tolerated. This approach, which reflects everyday clinical practice, further enhances data generalizability.

Conclusions

Our results support the use of combined ACE inhibitor and ARB therapy to achieve remission of proteinuria and stabilize or even improve kidney function in children with chronic renal parenchymal disease. Provided children are closely monitored and treatment is cautiously tailored to individual response, this approach could be safely applied in day-to-day hospital practice.

Supplementary Material

Algorithm describing the key steps of the Remission Clinic intervention protocol. Hydrochlorothiazide (2 mg/kg, if eGFR > 40 ml/min/1.73m2) or furosemide (1 mg/kg, if eGFR < 40 ml/min/1.73m2) could be added at any time as deemed clinically appropriate to control edema and hyperkalemia, and maximize the antihypertensive and antiproteinuric effect of RAS inhibition.

STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cohort studies

Changes in proteinuria over the follow-up period

Changes in proteinuria adjusted for BSA over the follow-up period

Acknowledgments

The Authors thank Nadia Rubis for monitoring the study data and the staff of the Outpatient Clinics of ASST Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII of Bergamo, for the help in patient monitoring and care.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards: The research ethics boards of all participating hospitals approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents and/or the patients.

Financial Disclosure: None.

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this work.

References

- 1.Ruggenenti P, Cravedi P, Remuzzi G. Mechanisms and treatment of CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1917–1928. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012040390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Time to abandon microalbuminuria? Kidney Int. 2006;70:1214–1222. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Remuzzi G, Investigators GG. Retarding progression of chronic renal disease: the neglected issue of residual proteinuria. Kidney Int. 2003;63:2254–2261. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortinovis M, Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Progression, Remission and Regression of Chronic Renal Diseases. Nephron. 2016 doi: 10.1159/000445844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arbus GS, Poucell S, Bacheyie GS, Baumal R. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: three types of clinical response. J Pediatr. 1982;101:40–45. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remuzzi A, Gagliardini E, Sangalli F, Bonomelli M, Piccinelli M, Benigni A, Remuzzi G. ACE inhibition reduces glomerulosclerosis and regenerates glomerular tissue in a model of progressive renal disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1124–1130. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Remuzzi A, Sangalli F, Macconi D, Tomasoni S, Cattaneo I, Rizzo P, Bonandrini B, Bresciani E, Longaretti L, Gagliardini E, Conti S, Benigni A, Remuzzi G. Regression of Renal Disease by Angiotensin II Antagonism Is Caused by Regeneration of Kidney Vasculature. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:699–705. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014100971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson JC, Adler S, Burkart JM, Greene T, Hebert LA, Hunsicker LG, King AJ, Klahr S, Massry SG, Seifter JL. Blood pressure control, proteinuria, and the progression of renal disease. The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:754–762. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gherardi G, Gaspari F, Benini R, Remuzzi G. Renal function and requirement for dialysis in chronic nephropathy patients on long-term ramipril: REIN follow-up trial. Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia (GISEN). Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy. Lancet. 1998;352:1252–1256. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S, Investigators RS. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Group TG. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia) Lancet. 1997;349:1857–1863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harambat J, van Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, Tizard EJ. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1939-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trachtman H, Gauthier B. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy on proteinuria in children with renal disease. J Pediatr. 1988;112:295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lama G, Salsano ME, Pedulla M, Grassia C, Ruocco G. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and reflux nephropathy: 2-year follow-up. Pediatr Nephrol. 1997;11:714–718. doi: 10.1007/s004670050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb NJ, Shahinfar S, Wells TG, Massaad R, Gleim GW, Santoro EP, Sisk CM, Lam C. Losartan and enalapril are comparable in reducing proteinuria in children. Kidney Int. 2012;82:819–826. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webb NJ, Shahinfar S, Wells TG, Massaad R, Gleim GW, McCrary Sisk C, Lam C. Losartan and enalapril are comparable in reducing proteinuria in children with Alport syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:737–743. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Group ET, Wuhl E, Trivelli A, Picca S, Litwin M, Peco-Antic A, Zurowska A, Testa S, Jankauskiene A, Emre S, Caldas-Afonso A, Anarat A, Niaudet P, Mir S, Bakkaloglu A, Enke B, Montini G, Wingen AM, Sallay P, Jeck N, Berg U, Caliskan S, Wygoda S, Hohbach-Hohenfellner K, Dusek J, Urasinski T, Arbeiter K, Neuhaus T, Gellermann J, Drozdz D, Fischbach M, Moller K, Wigger M, Peruzzi L, Mehls O, Schaefer F. Strict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in children. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1639–1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bomback AS, Klemmer PJ. The incidence and implications of aldosterone breakthrough. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007;3:486–492. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruggenenti P, Schieppati A, Remuzzi G. Progression, remission, regression of chronic renal diseases. Lancet. 2001;357:1601–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04728-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingelfinger JR. Blood-pressure control and delay in progression of kidney disease in children. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1701–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0908183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell R, Sangalli F, Perticucci E, Aros C, Viscarra C, Perna A, Remuzzi A, Bertocchi F, Fagiani L, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P. Effects of combined ACE inhibitor and angiotensin II antagonist treatment in human chronic nephropathies. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1094–1103. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruggenenti P, Brenner BM, Remuzzi G. Remission achieved in chronic nephropathy by a multidrug approach targeted at urinary protein excretion. Nephron. 2001;88:254–259. doi: 10.1159/000045998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruggenenti P, Perticucci E, Cravedi P, Gambara V, Costantini M, Sharma SK, Perna A, Remuzzi G. Role of remission clinics in the longitudinal treatment of CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1213–1224. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007090970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daina E, Cravedi P, Alpa M, Roccatello D, Gamba S, Perna A, Gaspari F, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P. A multidrug, antiproteinuric approach to alport syndrome: a ten-year cohort study. Nephron. 2015;130:13–20. doi: 10.1159/000381480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remission Clinic Task F, Clinical Research Center “Aldo e Cele D. The Remission Clinic approach to halt the progression of kidney disease. J Nephrol. 2011;24:274–281. doi: 10.5301/JN.2011.7763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panteghini M, Division IS. Enzymatic assays for creatinine: time for action. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46:567–572. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz GJ, Munoz A, Schneider MF, Mak RH, Kaskel F, Warady BA, Furth SL. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:629–637. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Standardizing anthropometric measures in children and adolescents with functions for egen:Update. The Stata Journal. 2013;13:366–378. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter JR. Journal of Statistical Software 45 2011;45(5) 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verbraecken J, Van de Heyning P, De Backer W, Van Gaal L. Body surface area in normal-weight, overweight, and obese adults. A comparison study. Metabolism. 2006;55:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgess E, Muirhead N, Rene de Cotret P, Chiu A, Pichette V, Tobe S, Investigators S. Supramaximal dose of candesartan in proteinuric renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:893–900. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruggenenti P, Cravedi P, Remuzzi G. Proteinuria: Increased angiotensin-receptor blocking is not the first option. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:367–368. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cravedi P, Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Proteinuria should be used as a surrogate in CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:301–306. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruggenenti P, Bettinaglio P, Pinares F, Remuzzi G. Angiotensin converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism and renoprotection in diabetic and nondiabetic nephropathies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1511–1525. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04140907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Investigators O, Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, Schumacher H, Dagenais G, Sleight P, Anderson C. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Proteinuria: Is the ONTARGET renal substudy actually off target? Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:436–437. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, Brophy M, Conner TA, Duckworth W, Leehey DJ, McCullough PA, O'Connor T, Palevsky PM, Reilly RF, Seliger SL, Warren SR, Watnick S, Peduzzi P, Guarino P. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1892–1903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parving HH, Brenner BM, McMurray JJ, de Zeeuw D, Haffner SM, Solomon SD, Chaturvedi N, Persson F, Desai AS, Nicolaides M, Richard A, Xiang Z, Brunel P, Pfeffer MA. Cardiorenal end points in a trial of aliskiren for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2204–2213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Algorithm describing the key steps of the Remission Clinic intervention protocol. Hydrochlorothiazide (2 mg/kg, if eGFR > 40 ml/min/1.73m2) or furosemide (1 mg/kg, if eGFR < 40 ml/min/1.73m2) could be added at any time as deemed clinically appropriate to control edema and hyperkalemia, and maximize the antihypertensive and antiproteinuric effect of RAS inhibition.

STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cohort studies

Changes in proteinuria over the follow-up period

Changes in proteinuria adjusted for BSA over the follow-up period