Abstract

Background & Aims

Intestinal fibrosis is a critical complication of Crohn’s disease (CD). Current in vitro models of intestinal fibrosis cannot model the complex intestinal architecture, while in vivo rodent models do not fully recapitulate human disease and have limited utility for large-scale screening. Here, we exploit recent advances in stem cell derived human intestinal organoids (HIOs) as a new human model of fibrosis in CD.

Methods

Human pluripotent stem cells were differentiated into HIOs. We identified myofibroblasts, the key effector cells of fibrosis, by immunofluorescence staining for alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), vimentin, and desmin. We examined the fibrogenic response of HIOs by treatment with transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) in the presence or absence of the anti-fibrotic drug spironolactone. Fibrotic response was assayed by expression of fibrogenic genes (COL1A1 (collagen, type I, alpha 1), ACTA2 (alpha smooth muscle actin), FN1 (fibronectin 1), MYLK (myosin light chain kinase), and MKL1 (megakaryoblastic leukemia (translocation) 1)) and proteins (αSMA).

Results

Immunofluorescent staining of organoids identified a population of myofibroblasts within the HIO mesenchyme. TGFβ stimulation of HIOs produced a dose-dependent pro-fibrotic response. Spironolactone treatment blocked the fibrogenic response of HIOs to TGFβ.

Conclusions

HIOs contain myofibroblasts and respond to a pro-fibrotic stimulus in a manner that is consistent with isolated human myofibroblasts. HIOs are a promising model system that might bridge the gap between current in vitro and in vivo models of intestinal fibrosis in IBD.

Keywords: Organoid, Myofibroblasts, TGFβ, fibrosis model, drug screening

Introduction

Fibrosis is the final common pathway to organ failure in diseases of the heart, kidney, liver, lung, and intestine (Collard et al., 2012; Collins et al., 2010; Neff et al., 2011; O'Connell and Bristow, 1994; Rieder et al., 2007). Intestinal fibrosis, for which no pharmacological therapies exist, is the cause for intestinal obstruction and surgical resection in the majority of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) (Andres and Friedman, 1999; Sands et al., 2003).

Current in vitro and in vivo intestinal fibrosis models have both advantages and disadvantages. In vitro models of intestinal fibrosis have focused on the myofibroblast, the key effector cell of fibrosis, using fibrogenic cytokine stimulation (e.g. TGFβ) and mechanical stress (e.g. matrix stiffness), as we and others have demonstrated (Hinz, 2010; Horowitz et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2012c; Liu et al., 2010). However, these culture models do not reflect 3D architecture and lack the multiple, specialized cell types of the intestinal structure; therefore they do not fully recapitulate in vivo physiology. Rodent models of intestinal fibrosis, including the rat 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) (Kim et al., 2008) and mouse S. typhimurium (Grassl et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2012b) models, have limited utility because they are not physiologically representative of human disease, and are expensive and inefficient, thus impractical for high-throughput screening.

Recent advances in the differentiation and development of intestinal tissue have resulted in the novel technique of generating human intestinal organoids (HIOs) in culture (McCracken et al., 2011). HIOs are generated from normal human pluripotent stem cells, recapitulating embryonic intestinal development and contain both epithelium and mesenchyme, including myofibroblasts (Spence et al., 2011). Moreover, they have proven to accurately represent in vivo physiology in a number of contexts (Chen et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2014; Leslie et al., 2014). Given that HIOs are the only organoid model that possesses both epithelium and mesenchyme, and that the mesenchymal layer is a major effector in fibrosis, we reasoned that HIOs could be used as a viable in vitro model of human intestinal fibrosis to bridge the gap between in vitro and in vivo models of intestinal fibrosis, enabling the study of multi-lineage human cells in a physiologically relevant environment, while being amenable to high-throughput drug screening (Astashkina and Grainger, 2014; Ranga et al., 2014). In this study we explore the potential for HIOs to be used as a model of intestinal fibrosis and as a tool for screening anti-fibrotic drugs, using spironolactone as our proof-of-concept drug because of its proven effectiveness in cardiac fibrosis (Pitt et al., 1999).

Materials and Methods

Unless otherwise specified, all chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO.

HIO Culture

All work was approved by the University of Michigan Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee (HPSCRO). Human embryonic stem cells (H9, Wicell Research Institute, Madison, WI) were differentiated into human intestinal organoids (HIOs) as described previously (McCracken et al., 2011; Spence et al., 2011). For the purpose of this study, organoids with high mesenchymal cell composition were chosen, as opposed to cyst-like, epithelial-high organoids. For TGFβ treatment, HIOs were embedded in growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, catalog # 356231).

Immunofluorescence Staining and Imaging

Cultured HIOs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in PBS, washed in PBS, and embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), then sliced on a cryotome and mounted on Fisherbrand Superfrost Plus slides. The tissue was, then blocked and permeabilized in PBS containing 5% goat serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 0.5% Triton-X 100 (LabChem, Pittsburgh, PA) for 1 hour at 37 degrees C. An additional blocking step was performed using SFX signal enhancer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies to vimentin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, catalog # SAB4503083) or to desmin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, catalog # ab8976) at 1:100 for 2 hours. Slides were washed with 0.05% Tween 20 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in PBS, followed by incubation with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Detection of αSMA was performed with 30 minute incubation using Cy3 conjugated mouse anti-αSMA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 1:200, co-stained with 4, 6’ diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 1:1000, to visualize nuclei. Images were acquired using Olympus BX60 microscope and DP72 camera, with CellSens Standard imaging software, version 1.11 (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). Images were merged using ImageJ software.

TGFβ Fibrogenesis Model

Recombinant human TGFβ was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). TGFβ responsiveness was assayed by treatment of HIOs with increasing amounts of TGFβ (0.5 to 5 ng/mL) for 48 or 96 hr. To determine the effect of spironolactone, HIOs were co-treated with 2 ng/mL TGFβ and 25 to 500 uM spironolactone prior to harvest for molecular analysis.

Real-Time PCR Analysis

RNA was extracted from HIOs using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNAs were treated with RNase-free DNase prior to cDNA synthesis using the First Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The analysis of gene expression was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (QPCR) of collagen-1 A1 (COLA1), myosin light chain kinase (MYLK), fibronectin 1 (FN1), MKL1 (MRTF-A) genes and GAPDH was performed with the TaqMan gene expression assays (ABI, Foster City, CA). QPCR was performed using a Stratagene Mx3000P (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) or iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) real-time PCR system. αSMA (ACTA2) gene expression was determined with the SYBR Green assay using the following primers (ACTA2-F 5’-AATGCAGAAGGAGATCACGC-3’, ACTA2-R 5’-TCCTGTTTGCTGATCCACATC-3’) as previously described(Johnson et al., 2014). Cycling conditions were 95° C 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95° C 15 seconds and 62° C 60 seconds. ΔΔCt were calculated from GAPDH expression.

Preparation of Protein Lysates from HIO

HIOs were excised from Matrigel, pooled (9–12 organoids were pooled per sample), washed in ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), washed for 1 hour in Cell Recovery Solution (Corning, Bedford, MA), followed by additional PBS washes, then were lysed in buffer containing 50mMTris pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1.5mM MgCl2, 5mM EGTA, 1 % glycerol, plus Complete EDTA Free Protease and Phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), Sodium Pyrophosphate (30mM), Sodium Fluoride (50mM), and Sodium Orthovanadate (100uM). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation prior to loading 10–40 µg total protein on SDS-PAGE gel.

Western Blot Analysis

Total protein was separated by SDS–PAGE and probed for αSMA as previously described (Johnson et al., 2012c). αSMA primary antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, catalog # A5228) was used at 1:400.

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed independently at least three times with similar results; findings from one representative experiment are presented. Comparisons across treatment groups were analyzed with analysis of variance (ANOVA), while pairwise comparisons between two groups were performed with Student’s t-test.

All authors had access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Results and Discussion

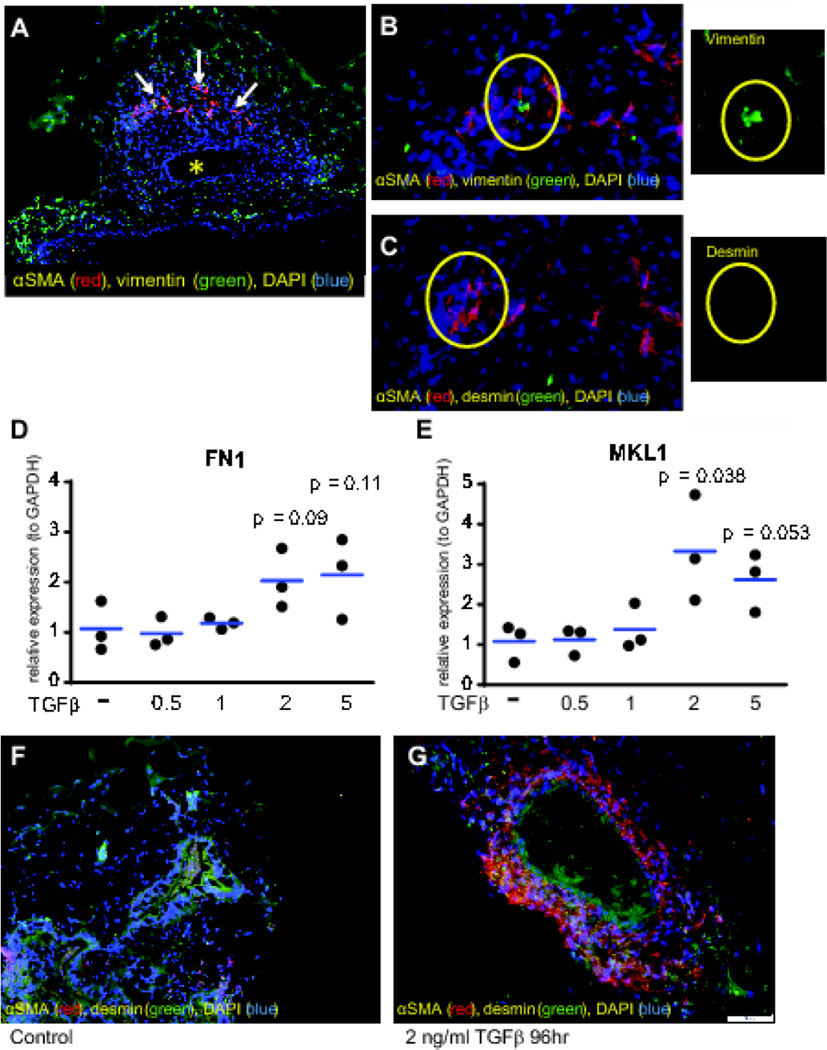

Myofibroblasts are the key effector cells of fibrosis (Powell et al., 1999). Recent advances in 3-dimensional culture have enabled the in vitro growth of organoids that recapitulate the multilayer structure of the human intestine (McCracken et al., 2011). A previous study identified a population of myofibroblasts in HIOs (Spence et al., 2011). By immunofluorescence (IF) staining, we showed that HIOs from genetically normal human embryonic stem cells (hESCs, line H9) organize into complex structures comprised of a lumen (asterisk) surrounded by endodermally derived epithelium, and mesodermally derived mesenchymal layers (Figure 1A). We observed the organization of a population of intestinal myofibroblasts (white arrows) adjacent to the intestinal epithelium (Figure 1 A). These cells were identified as αSMA+/vimentin+/desmin− myofibroblasts (Figure 1 B and C, see high magnification inset).

Figure 1.

HIOs contain myofibroblasts and are activated by TGFβ. (A) Morphology (10× magnification) of representative HIO illustrating the presence of a well-defined lumen (asterisk) and a population αSMA+ cells (red staining, white arrows). (B,C) αSMA + (red) cells were identified as resident myofibroblasts (αSMA +, vimentin+, desmin−) by staining with vimentin (green in B), and desmin (green in C), 20× magnification. Individual representative vimentin+/desmin− myofibroblasts (circled) are shown in the insets. (D,E) Gene expression as determined by qPCR for pro-fibrotic genes FN1 (D) and MKL-1 (E) in HIOs treated with increasing amounts of TGFβ (0.5, 1, 2, 5 ng/mL) for 48 hrs. The expression of pro-fibrotic genes was normalized to GAPDH using the ΔΔCt method. Results are from 3 independent experiments. Statistical comparisons are made between the untreated and TGFβ-treated groups using the Paired Student’s t-test. (F,G) Activation of myofibroblasts within the HIOs by TGFβ. αSMA (red) and vimentin (green) was markedly induced in TGFβ-treated HIO (G). Vimentin is stained green in Figure 1 F and G. The scale bar represents 50 µM.

Next, we determined whether HIOs would respond to TGFβ treatment with an increase in αSMA-expressing cells, indicating fibrogenic activation. In previous studies (Johnson et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2013), we demonstrated that isolated human colonic myofibroblasts respond to TGFβ by inducing fibrogenic genes. To determine the effective dose of TGFβ for HIOs, we first performed a 48-hour TGFβ dose-response experiment (0.5 to 5 ng/mL TGFβ) and assayed for gene expression of the ECM components COL1A1 and FN1, the myofibroblast marker and component of actin stress fibers ACTA2, the actin contractile gene MYLK, and the fibrogenic transcription factor MKL1. In contrast to isolated myofibroblasts, in HIOs, no induction of COL1A1, FN1, ACTA2, or MYLK was observed at 48 hours. However, MKL1 gene expression was induced (3-fold), and a trend towards induction of FN1 gene expression was also observed at 48 hours, with 2 ng/mL TGFβ (Figure 1 D, E). Because myofibroblasts in HIOs are sequestered from their environment within layers of other cell populations (Figure 1 A), we postulated that a longer treatment would be necessary to induce a robust fibrogenic response in HIOs. Based on these results demonstrating a modest fibrogenic response starting at 2ng/mL, we treated HIOs with 2 ng/mL TGFβ for 96 hours, and found marked induction of αSMA (red, Figure 1 G), compared to untreated HIOs (Figure 1 F).

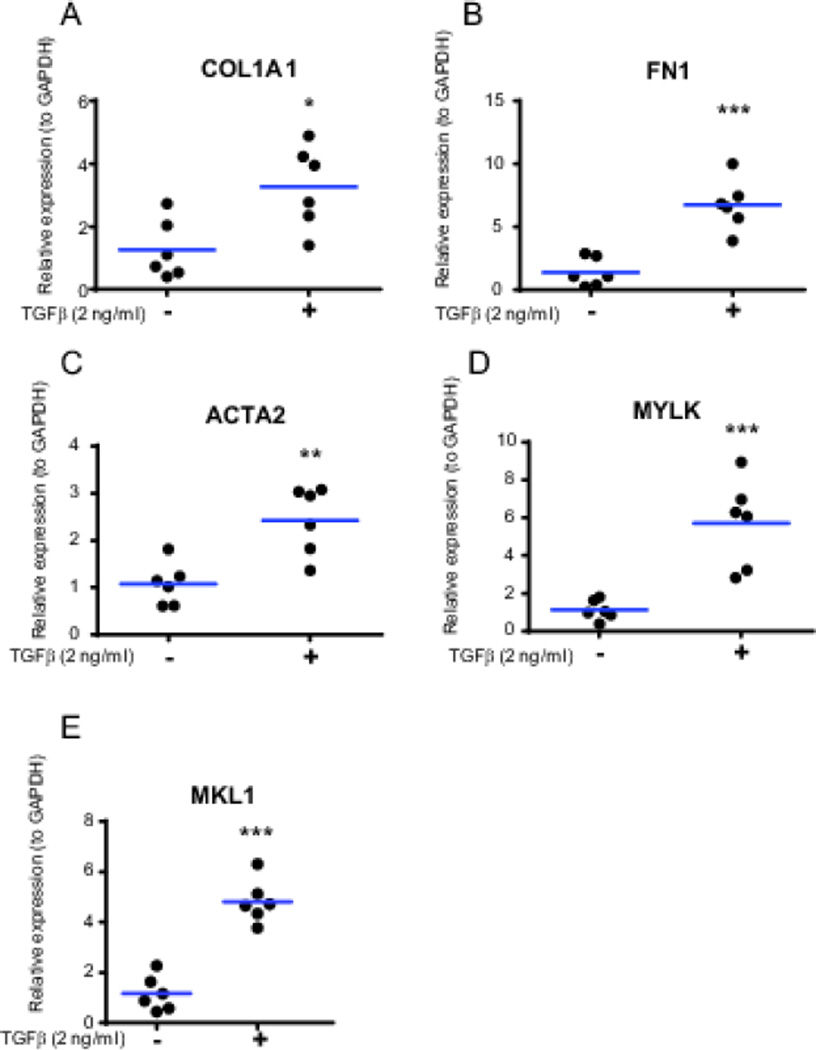

To further validate the fibrogenic response observed in Figure 1F and 1G, we treated the HIOs with 2 ng/mL TGFβ for 96 hours and then analyzed fibrogenic gene expression by QRT-PCR. Supporting the immunofluorescence data, significant induction of several fibrogenic genes in HIOs was observed at 96 hours, including COL1A1 (2.6-fold), FN1 (4.8-fold), ACTA2 (2.3-fold), MYLK (5.1-fold), and MKL1 (4.1-fold), as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Induction of fibrogenic gene expression in HIO by TGFβ. Matrigel-embedded HIOs were cultured for 96 hours in the presence or absence of TGFβ (2 ng/mL). (A) Expression of COL1A1, (B) Expression of FN1, (C) Expression of ACTA2, (D) Expression of MYLK, (E) Expression of MKL1. Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH expression. Statistical comparisons are made between untreated and TGFβ-treated organoids using the Paired Student t test, *p < 0.05, ** p <0.01, ***p<0.001. Results are from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate (total n=6).

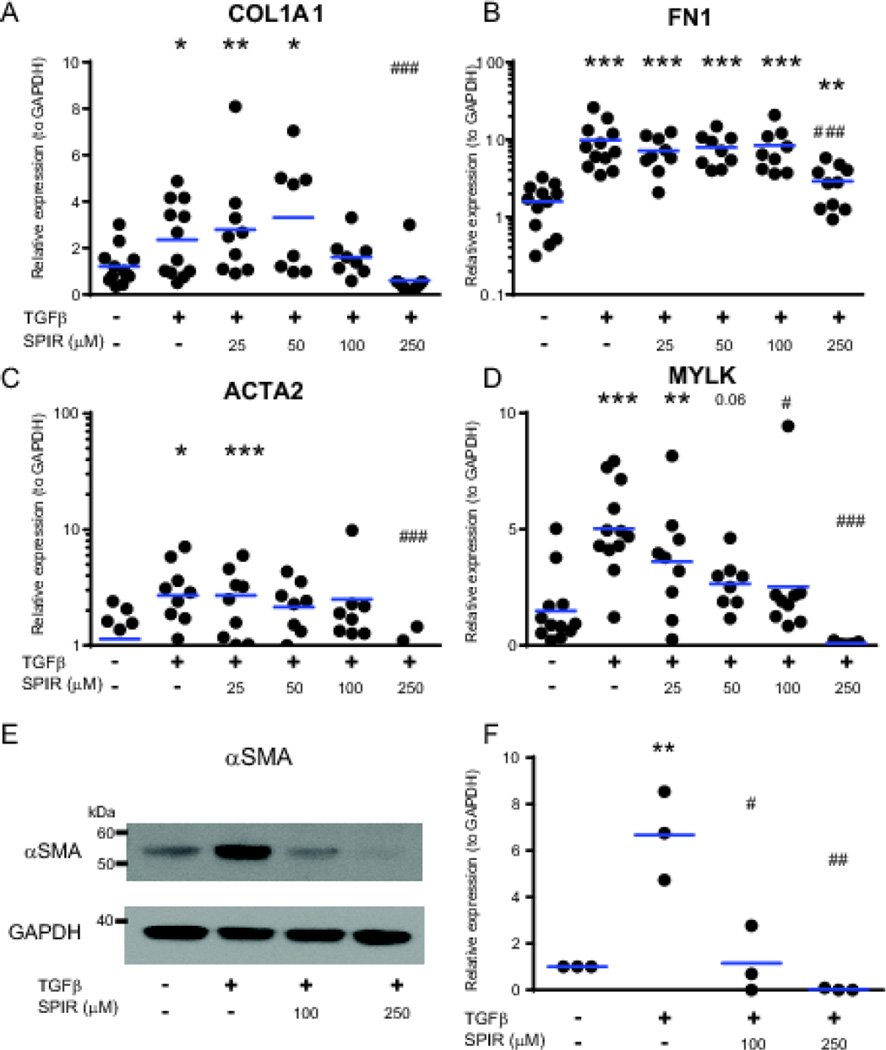

Next, to show proof-of-concept that HIOs can be used to test anti-fibrotic drugs, we determined whether the TGFβ-mediated fibrogenic response of HIOs could be reversed by treatment with spironolactone. Spironolactone is a competitive aldosterone receptor antagonist that is commonly used as an anti-fibrotic medication in heart patients, and has proven protective in several rodent models of fibrosis (Ersoy et al., 2007; Gullulu et al., 2006; Nishimura et al., 2008; Rajagopalan and Pitt, 2003). Previously, our group determined that spironolactone was anti-fibrotic in isolated human colonic myofibroblasts and repressed TGFβ-mediated induction of pro-fibrotic genes and proteins (Johnson et al., 2012a). To determine whether spironolactone could prevent TGFβ-induced fibrogenic gene and protein expression in HIOs, we analyzed the expression of fibrogenic genes and proteins in HIOs by qPCR and Western blot after 96 hours of co-treatment of various concentrations of spironolactone with 2 ng/mL TGFβ. Spironolactone (250 µM) repressed TGFβ-stimulated induction of COL1A1(3.9-fold), FN1 (3.4-fold), ACTA2 (3.9-fold), and MYLK (66-fold), as seen in Figure 3 A–D. The effect of spironolactone on αSMA protein expression was even more pronounced, reversing the TGFβ-mediated induction of αSMA protein expression at a concentration of 100 µM (Figure 3 E and F).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of TGFβ-mediated induction of fibrogenic genes by spironolactone (SPIR) in HIOs. Organoids were embedded in Matrigel and cultured for 96 hours in the presence or absence of TGFβ (2 ng/mL) and 0, 25, 50, 100, and 250 µM spironolactone. Gene expression analysis: A–D. (A) Expression of COL1A1, (B) Expression of FN1, (C) Expression of ACTA2, (D) Expression of MYLK. The expression of pro-fibrotic genes was normalized to GAPDH using the ΔΔCt method. Results are from 3 independent experiments. (E). Representative αSMA Western blot of HIOs treated with TGFβ (2 ng/mL) and 100 or 250 µM SPIR for 96 hours. (F) Quantitation of αSMA protein expression in response to co-treatment with TGFβ and either 100 or 250 µM SPIR. HIOs were treated for 96 hours with 2 ng/mL TGFβ. Western data from 3 independent HIO experiments were quantified using ImageJ. αSMA band density was normalized to GAPDH band density, and within each experiment, treatment groups were normalized to untreated. Horizontal bars represent the geometric mean of each group. Statistical comparisons are made between untreated HIO and TGFβ-treated or TGFβ and SPIR treated HIOs using the Paired Student t test are denoted with asterisks (*p < 0.05, ** p <0.01, ***p<0.001). Statistical comparisons between TGFβ-treated or TGFβ and SPIR treated HIOs are denoted with a pound sign (# p < 0.05, ## p <0.01, ### p<0.001).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that HIOs can be used to model intestinal fibrosis, and to test the effectiveness of anti-fibrotic drugs. Study of the pathology of fibrosis in inflammatory bowel disease has, until recently, depended upon animal models that are complex, expensive, and possibly not relevant to the disease state (Brenna et al., 2013; Mestas and Hughes, 2004; Neurath et al., 2000), or 2D cell culture models that are reductionist and artificial. For example, the surface of a plastic culture dish is orders of magnitude stiffer than intestinal tissue (Mih et al., 2011), and induces an activated myofibroblast phenotype, characterized by increased number and organization of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions (Hinz, 2010). Because they contain multiple cell types and 3D architecture physiologically similar to the human intestine, our data suggest that HIOs are a viable new model to study fibrosis related to Crohn’s disease.

Highlights.

Induction of intestinal fibrosis was modeled in human intestinal organoids (HIOs).

HIOs recapitulate the fibrogenic response of isolated myofibroblasts.

Spironolactone treatment blocked the fibrogenic response of HIOs to TGFβ.

HIOs are a promising model of intestinal fibrosis induction and treatment.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: JRS is supported by career development grants from the NIDDK (K01DK091415) and the March of Dimes (Basil O’Connor starter scholar award). ESR, LAJ, SH, JRS, and PDRH are supported by the Michigan Gastrointestinal Peptide Research Center (MGPRC), (NIDDK 5P30DK034933).

The authors thank Stacy Finkbeiner and Chris Altheim for technical assistance with preparing organoid sections for immunofluorescence staining.

Abbreviations

- ACTA2

alpha smooth muscle actin (gene)

- αSMA

alpha smooth muscle actin (protein)

- CD

Crohn’s Disease

- COL1A1

collagen, type I, alpha 1

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FN1

fibronectin 1

- HIO

Human Intestinal Organoids

- IF

Immunofluorescence

- MKL1

megakaryoblastic leukemia (translocation) 1

- MYLK

myosin light chain kinase

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions:

ESR- Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript.

LAJ- Analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.

SH – Acquisition and analysis of data; technical and material support.

JRS and PDRH – Study concept and design, obtained funding, critical revision of the manuscript.

Disclosures: All authors have nothing to disclose. No conflicts of interest exist.

References

- Andres PG, Friedman LS. Epidemiology and the natural course of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1999;28:255–281. vii. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astashkina A, Grainger DW. Critical analysis of 3-D organoid in vitro cell culture models for high-throughput drug candidate toxicity assessments. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;69–70:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenna O, et al. Relevance of TNBS-colitis in rats: a methodological study with endoscopic, histologic and Transcriptomic [corrected] characterization and correlation to IBD. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, et al. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008;18:997–1006. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YJ, et al. De novo formation of insulin-producing "neo-beta cell islets" from intestinal crypts. Cell Rep. 2014;6:1046–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collard HR, et al. Burden of illness in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Med Econ. 2012;15:829–835. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.680553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AJ, et al. Excerpts from the US Renal Data System 2009 Annual Data Report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:S1–S420. A6–A7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersoy R, et al. The effects of irbesartan and spironolactone in prevention of peritoneal fibrosis in rats. Perit Dial Int. 2007;27:424–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassl GA, et al. Chronic enteric salmonella infection in mice leads to severe and persistent intestinal fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:768–780. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullulu M, et al. Aldosterone blockage in proliferative glomerulonephritis prevents not only fibrosis, but proliferation as well. Ren Fail. 2006;28:509–514. doi: 10.1080/08860220600779033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B. The myofibroblast: paradigm for a mechanically active cell. J Biomech. 2010;43:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JC, et al. Survivin expression induced by endothelin-1 promotes myofibroblast resistance to apoptosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LA, et al. Spironolactone and colitis: increased mortality in rodents and in humans. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012a;18:1315–1324. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LA, et al. Intestinal fibrosis is reduced by early elimination of inflammation in a mouse model of IBD: impact of a "Top-Down" approach to intestinal fibrosis in mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012b;18:460–471. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LA, et al. Novel Rho/MRTF/SRF inhibitors block matrix-stiffness and TGF-beta-induced fibrogenesis in human colonic myofibroblasts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:154–165. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000437615.98881.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LA, et al. Matrix stiffness corresponding to strictured bowel induces a fibrogenic response in human colonic fibroblasts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:891–903. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182813297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LA, et al. CARD-024, a vitamin D analog, attenuates the pro-fibrotic response to substrate stiffness in colonic myofibroblasts. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012c;93:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, et al. Noninvasive ultrasound elasticity imaging (UEI) of Crohn's disease: animal model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:902–912. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie JL, et al. Persistence and toxin production by Clostridium difficile within human intestinal organoids results in disruption of epithelial paracellular barrier function. Infect Immun. 2014 doi: 10.1128/IAI.02561-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, et al. Feedback amplification of fibrosis through matrix stiffening and COX-2 suppression. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:693–706. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken KW, et al. Generating human intestinal tissue from pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1920–1928. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestas J, Hughes CC. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J Immunol. 2004;172:2731–2738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mih JD, et al. A multiwell platform for studying stiffness-dependent cell biology. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff GW, et al. The current economic burden of cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:661–671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurath M, et al. TNBS-colitis. Int Rev Immunol. 2000;19:51–62. doi: 10.3109/08830180009048389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura H, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade ameliorates peritoneal fibrosis in new rat peritonitis model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F1084–F1093. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00565.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell JB, Bristow MR. Economic impact of heart failure in the United States: time for a different approach. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1994;13:S107–S112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt B, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DW, et al. Myofibroblasts. II. Intestinal subepithelial myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C183–C201. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.2.C183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan S, Pitt B. Aldosterone as a target in congestive heart failure. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:441–457. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranga A, et al. Drug discovery through stem cell-based organoid models. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;69–70:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder F, et al. Wound healing and fibrosis in intestinal disease. Gut. 2007;56:130–139. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.090456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands BE, et al. Risk of early surgery for Crohn's disease: implications for early treatment strategies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2712–2718. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence JR, et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature. 2011;470:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]