The development of catalysts for electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide offers an attractive approach to transforming this greenhouse gas into value-added carbon products with sustainable energy input.

The development of catalysts for electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide offers an attractive approach to transforming this greenhouse gas into value-added carbon products with sustainable energy input.

Abstract

The development of catalysts for electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide offers an attractive approach to transforming this greenhouse gas into value-added carbon products with sustainable energy input. Inspired by natural bioinorganic systems that feature precisely positioned hydrogen-bond donors in the secondary coordination sphere to direct chemical transformations occurring at redox-active metal centers, we now report the design, synthesis, and characterization of a series of iron tetraphenylporphyrin (Fe-TPP) derivatives bearing amide pendants at various positions at the periphery of the metal core. Proper positioning of the amide pendants greatly affects the electrocatalytic activity for carbon dioxide reduction to carbon monoxide. In particular, derivatives bearing proximal and distal amide pendants on the ortho position of the phenyl ring exhibit significantly larger turnover frequencies (TOF) compared to the analogous para-functionalized amide isomers or unfunctionalized Fe-TPP. Analysis of TOF as a function of catalyst standard reduction potential enables first-sphere electronic effects to be disentangled from second-sphere through-space interactions, suggesting that the ortho-functionalized porphyrins can utilize the latter second-sphere property to promote CO2 reduction. Indeed, the distally-functionalized ortho-amide isomer shows a significantly larger through-space interaction than its proximal ortho-amide analogue. These data establish that proper positioning of secondary coordination sphere groups is an effective design element for breaking electronic scaling relationships that are often observed in electrochemical CO2 reduction.

Introduction

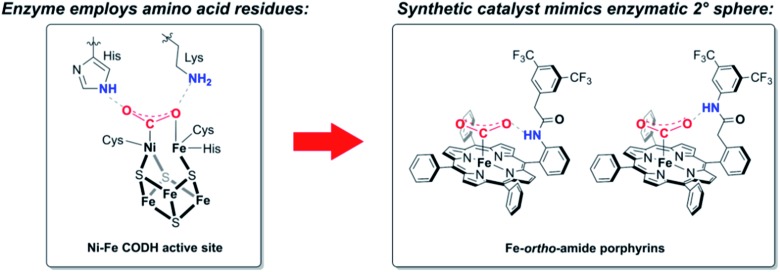

Environmental challenges associated with rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations and the promise of CO2 as a cheap and abundant C1 feedstock motivate the research into technologies to convert CO2 into value-added chemical products.1–3 Electrochemical reduction of CO2 offers an attractive approach to meet this goal using sustainable energy input, but the kinetic and thermodynamic barriers to CO2 activation provide significant chemical challenges, necessitating the development of catalysts that can promote CO2 reduction selectively over the competing background reduction of protons to hydrogen that can occur at comparable potentials. Indeed, despite broad interest in electrochemical CO2 reduction, molecular catalysis efforts have focused largely on a limited number of primary coordination sphere motifs, including metal complexes with porphyrins4–8 and aza-macrocycles,9–15 bipyridine,16–23 phosphine,24–26 and carbene27–29 ligands. In contrast, biological systems for CO2 redox catalysis, such as the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH) enzymes that catalyze the reversible interconversion of CO2 and CO, modulate activity using precisely positioned hydrogen-bond and proton-relay groups in the second coordination sphere.30 For example, second-sphere histidine and lysine residues in Ni–Fe CODH are positioned to stabilize a CO2-metal adduct and assist in C–O bond cleavage (Scheme 1).31–33

Scheme 1. The active site of Ni–Fe CO dehydrogenase, showing activated CO2 in red and the nearby network of hydrogen bond donor amino acid residues in blue (left), inspires the design of ortho-amide-functionalized Fe porphyrins examined in this work (right).

The aforementioned bioinorganic systems provide inspiration for the design of metal complexes bearing second-sphere groups to aid with activation or transformation of small molecule substrates. Notable advances in utilizing intramolecular hydrogen-bond donors to promote oxygen binding/activation include picket fence-, picnic basket-, and hangman porphyrins by Collman, Reed, C. K. Chang, and Nocera,34–39 dicopper complexes by Masuda,40,41 and tripodal systems by Borovik.42–45 Second-sphere donors have also been shown to play important roles in structural mimics of alcohol dehydrogenase,46,47 as well as in complexes for stoichiometric reduction of nitrite,48,49 nitrate,50 and nitrogen.51 Furthermore, second-sphere pendants have been incorporated into electrocatalyst scaffolds to facilitate protonation steps relevant to H2 evolution52–54 and O2 reduction,55,56 and to stabilize adducts or promote C–O bond cleavage in CO2 reduction.11,12,57–59 With specific regard to CO2 reduction, elegant work on iron tetraphenylporphyrins by Savéant, Costentin, and Robert has explored the use of phenol-based pendants for enhancing electrochemical CO2 reduction.57,60

Against this backdrop, we targeted the study of functionalized porphyrin complexes that could yield insight into questions of optimal placement of second-sphere pendants on a conserved first-sphere metal core. In this report, we describe the synthesis and electrochemical study of positional isomers of iron porphyrin CO2 reduction catalysts bearing pendant amides in the secondary coordination sphere. Intermolecular addition of a parent iron tetraphenylporphyrin catalyst, Fe-TPP, with an aryl amide additive results in a dose-dependent increase in CO2 reduction activity. Building upon this result, we designed and evaluated a series of positional isomers bearing intramolecular amide pendants in the ortho or para positions of the meso aryl ring, both proximal and distal to the porphyrin plane. Comparison of the catalytic activities of these isomers establishes that ortho orientation of the second-sphere groups is critical for an enhancement in catalysis. Correlation between the turnover frequency (TOF) and standard potential of the formal FeI/0 couple indicates that through-space interactions play a role in enhancing the rate of CO2 reduction for both ortho amide-functionalized catalysts, with the distal donor exhibiting a more significant through-space component. In contrast, such effects are largely absent in the para-functionalized congeners. These data provide a starting point for more sophisticated design of second-sphere functionalities as bioinspired design elements for redox catalysis of CO2 and other small-molecule substrates.

Results and discussion

Bis(aryl)amide additive promotes CO2 reduction with Fe porphyrin

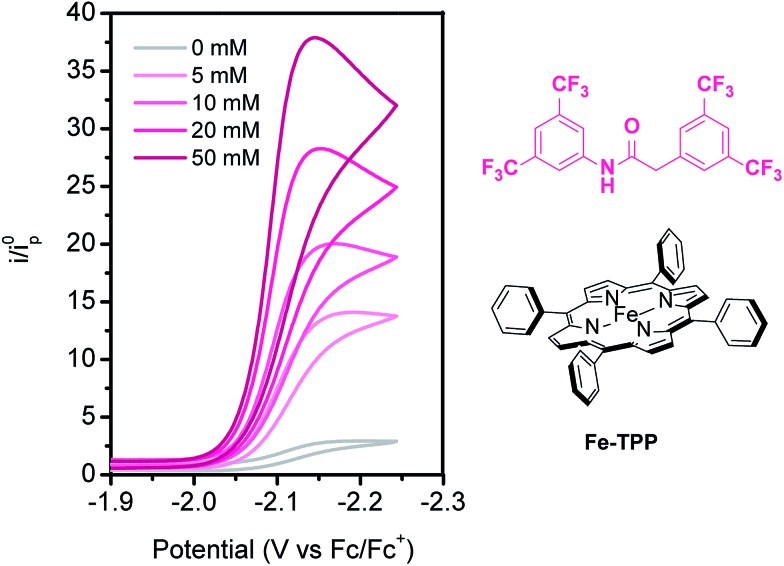

As a starting point to explore the use of amides as functional secondary coordination sphere pendants, we examined the effects of an electron-deficient aryl amide additive on CO2 reduction catalyzed by Fe-TPP. Titration of 3,5-[bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]amide to Fe-TPP in dimethylformamide (DMF) reveals a dose-dependent increase in catalytic activity (Fig. 1), with the additive acting as a proton source as well as a potential hydrogen bond donor/acceptor. Foot-of-the-wave analysis (FOWA), as described by Savéant, Costentin, Robert and co-workers,61 can be used to extract kinetic information from cyclic voltammetric data, especially in cases where a plateau current is not observed due to substrate consumption or catalyst inhibition. Using this approach, the rate of CO2 reduction was examined as a function of amide concentration under pseudo-first order conditions of excess CO2, and the rate was found to exhibit a first-order dependence on the amide additive (Fig. S1†). Cyclic voltammograms under a nitrogen atmosphere show a negligible change between 50 equivalents of amide additive and Fe-TPP alone, indicating that background processes such as proton reduction are likely to be minimal with this additive (Fig. S2†). With this pilot result in hand, we sought to explore the effects of introducing intramolecular amide substituents onto the porphyrin scaffold in a spatially well-defined fashion.

Fig. 1. Titration of 3,5-[bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]amide to Fe-TPP under CO2 showing current increases with increasing concentrations of amide. Conditions: 0.1 M TBAPF6 in DMF, 1 mM Fe-TPP.

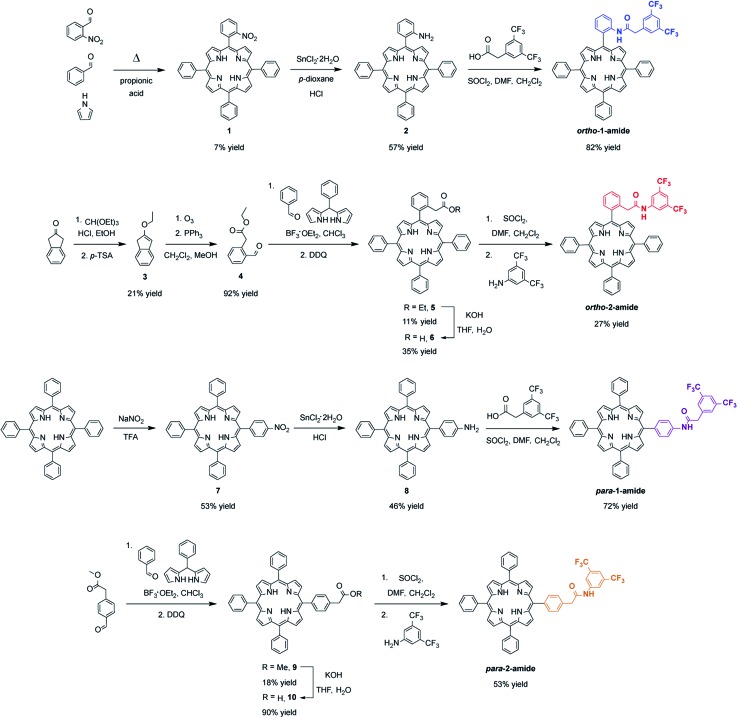

Synthesis of covalently-modified porphyrins bearing intramolecular amide groups

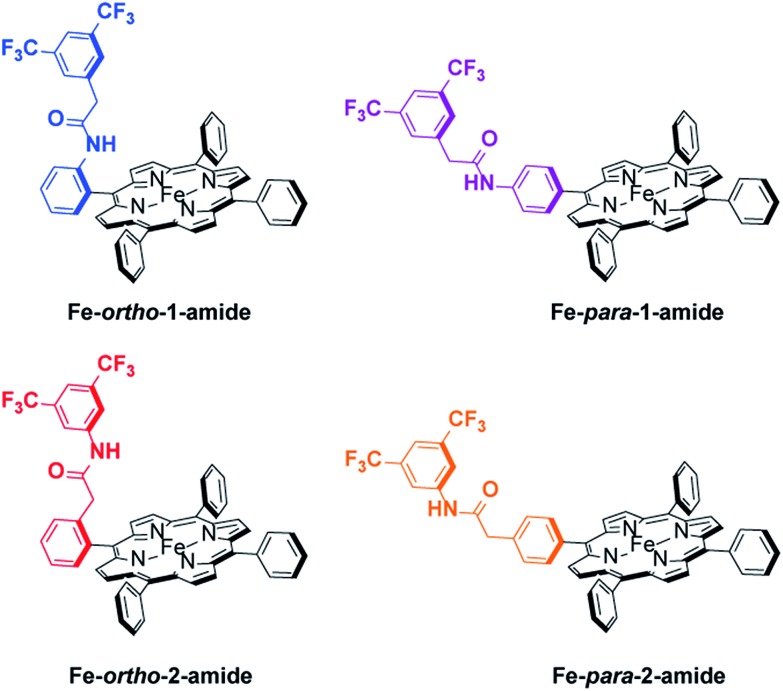

As only amide groups located at the ortho position of the porphyrin meso aryl rings are expected to engage in intramolecular proton donor- or hydrogen bonding interactions with CO2-derived intermediates bound at the iron center, we envisioned two positional isomers: ortho-1-amide, bearing the NH proximal to the porphyrin ring, and ortho-2-amide, bearing the NH distal to the porphyrin ring. Most porphyrin-based catalysts bearing second-sphere groups, especially those evaluated for CO2 reduction, feature these functionalities in the proximal location for reasons of synthetic practicality. We were interested in interrogating the effect of distal group positioning given a previous report showing that proximal second-sphere groups are located too far away from the metal center and are less effective at promoting oxygen binding at iron.36 The corresponding para-1-amide and para-2-amide porphyrins were targeted to serve as control compounds, where the amide NH group at the para position of the meso aryl rings is not expected to interact productively with CO2 or CO2-derived intermediates. The synthesis of all four functionalized porphyrin ligands is shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of ortho- and para-functionalized tetraphenylporphyrin ligands ortho-1-amide, ortho-2-amide, para-1-amide, and para-2-amide.

Condensation of 2-nitrobenzaldehyde and benzaldehyde with pyrrole results in the mono-(2-nitrophenyl)porphyrin starting material 1, which can be subsequently reduced to the mono-(2-aminophenyl)porphyrin synthon 2. Reaction with 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenylacyl chloride affords the proximal target ortho-1-amide. The distal ortho congener was prepared by condensation of 2-formylphenylacetic acid ethyl ester 4 (obtained in two steps from 2-indanone) and benzaldehyde with 5-phenyldipyrromethane to afford porphyrin 5. Subsequent hydrolysis, followed by in situ generation of the acyl chloride and reaction with 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)aniline affords ortho-2-amide. Porphyrin para-1-amide is obtained from mono-(4-aminophenyl)porphyrin 8, which is in turn prepared by regioselective para-nitration of tetraphenylporphyrin and subsequent reduction. A precursor to para-2-amide was accessed by condensation of commercially available 4-formylphenylacetic acid methyl ester and benzaldehyde with 5-phenyldipyrromethane to afford porphyrin 9. Hydrolysis, followed by in situ generation of the acyl chloride and reaction with 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)aniline, gave the desired ligand.

The iron complexes of the aforementioned porphyrin ligands were obtained by metalation with FeBr2 in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran in the presence of 2,6-lutidine as a base. All porphyrin ligands were characterized by 1H-, 13C-, and 19F-NMR spectroscopy, and freebase and metalloporphyrins were additionally characterized by UV-visible spectroscopy and ESI mass spectrometry (see ESI† for details).

Structural characterization of Zn–ortho-1-amide

We sought structural characterization of the amide-appended porphyrins to confirm the expected connectivity. Owing to a lack of success in obtaining suitable quality single crystals for structural characterization of the iron complexes, the corresponding zinc complexes were targeted. Porphyrin Zn–ortho-1-amide was prepared by metalation of the ligand with Zn(OAc)2. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown by vapor diffusion of water into a concentrated DMF solution. The solid-state structure is shown in Fig. 2, where a DMF molecule occupies the fifth axial coordination site. As is typical for pentacoordinate Zn porphyrins, the Zn atom is displaced from the porphyrin plane. As desired, the amide is oriented such that it may engage CO2 directly or act as a proton relay or hydrogen bond donor with CO2-bound intermediates during catalysis. We have been unable to obtain X-ray quality crystals of Zn–ortho-2-amide, perhaps due to enhanced flexibility of the amide group caused by the presence of the methylene spacer.

Fig. 2. Solid-state structure of Zn–ortho-1-amide. Non-coordinated solvent molecules and non-amide hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at the 50% level.

Cyclic voltammetry studies in dimethylformamide

With these positional isomers in hand (Scheme 3), we next evaluated their electrochemical characteristics under an inert atmosphere and under CO2. Cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of the functionalized iron porphyrins and parent Fe-TPP measured in DMF under argon atmosphere (0.1 M TBAPF6, 1 mM catalyst) show three distinct redox events corresponding to formal FeIII/II, FeII/I, and FeI/0 couples (Fig. S3†). Reversible FeI/0 couples are observed at a scan rate of 100 mV s–1 under these conditions. Scan rate-dependence studies show a linear correlation between peak current and (scan rate)1/2, indicating that all the complexes are freely diffusing under non-catalytic conditions (Fig. S4†). The FeI/0 standard potentials, E0cat, are given in Table 1 for each porphyrin complex. The E0cat potentials trend with the electron-withdrawing nature of the substituent, with ortho substituents exerting a larger electronic effect than para substituents: the proximal ortho amide is inductively electron-withdrawing, followed by the proximal para amide and unsubstituted TPP. The distal amides are rendered electron-donating by the methylene substituent, with the ortho positional isomer being more electron-rich than the para-substituted analogue.

Scheme 3. Positional isomers of amide-functionalized iron tetraphenylporphyrins examined in this work.

Table 1. Summary of electrochemical properties of iron porphyrin catalysts.

| Catalyst | E 0 cat a (V vs. Fc/Fc+) | TOFmax b (s–1) | log(TOFmax) | k cat c (M–2 s–1) | FECO d (%) |

| Fe–ortho-1-amide | –2.12 | 2.24 × 104 | 4.35 | 1.01 × 106 | 83 ± 3 |

| Fe–ortho-2-amide | –2.18 | 5.50 × 106 | 6.74 | 3.33 × 108 | 92 ± 2 |

| Fe–para-1-amide | –2.15 | 1.70 × 102 | 2.23 | 1.03 × 104 | 74 ± 8 |

| Fe–para-2-amide | –2.16 | 6.76 × 103 | 3.84 | 4.20 × 105 | 79 ± 8 |

| Fe-TPP | –2.15 | 6.76 × 102 | 2.83 | 2.13 × 105 | 90 ± 6 |

| Fe-TPP + 50 mM amide | –2.15 | 4.04 × 103 | 3.61 | 3.18 × 105 | — |

aThe standard reduction potential for the formal FeI/0 couple, E0cat, is reported as an average over three independent experiments.

bTOFmax values are reported in presence of 100 mM PhOH and 0.23 M CO2 except for the last entry, which is in presence of 50 mM amide additive and 0.23 M CO2.

c k cat values are reported as an average over three sets of experimental conditions (different [PhOH], 0.23 M CO2, in the regime where rate is linearly dependent on [PhOH]).

dFE for CO is reported as an average over three CPE experiments, see ESI for details.

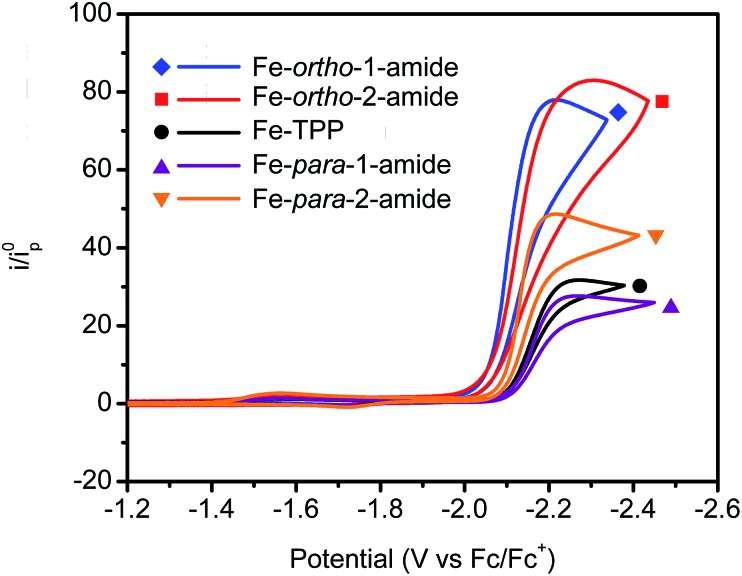

Under 1 atmosphere of CO2 and in the presence of phenol as an acid source, catalytic responses indicative of CO2 reduction are observed by cyclic voltammetry for all catalysts examined. In the presence of 100 mM phenol, Fe–ortho-1-amide exhibits a slightly more positive catalytic onset than Fe–ortho-2-amide, but both show significantly higher catalytic responses than the corresponding para-functionalized positional congeners or unfunctionalized Fe-TPP (Fig. 3). In the presence of low phenol concentrations (5 mM), Fe–ortho-2-amide shows a significantly larger peak current compared to all other catalysts and a comparable onset potential to that of Fe–ortho-1-amide (Fig. S5†). In contrast, at higher phenol concentrations of 250 mM, Fe–ortho-1-amide displays a larger peak current and a more anodic onset potential than Fe–ortho-2-amide (Fig. S5†). These findings suggest that the role of phenol may differ among the positional isomers, or that altered mechanisms of catalyst inactivation are at play.

Fig. 3. Cyclic voltammograms of amide-functionalized porphyrins and unfunctionalized Fe-TPP under CO2 atmosphere. Conditions: 1 mM catalyst, 100 mM phenol, 0.1 M TBAPF6 in DMF, saturated with CO2 (0.23 M); scan rate 100 mV s–1. i represents current under catalytic conditions; i0p represents the cathodic peak height of the formal FeII/I couple under inert atmosphere.

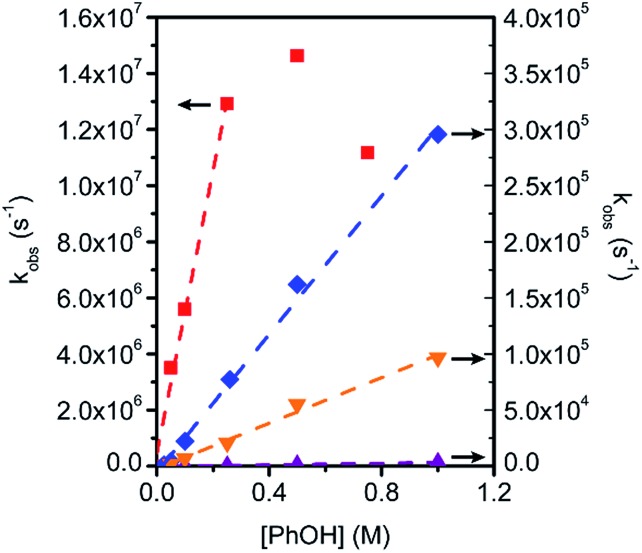

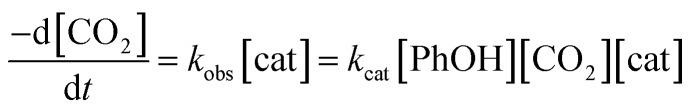

To gain further insight into CO2 reduction catalyzed by this series of amide-functionalized porphyrins, the observed rate constants (kobs = TOFmax, s–1) determined by FOWA were examined as a function of phenol and CO2 concentration. Under pseudo-first order conditions, all four functionalized catalysts display first-order dependence on phenol concentration (Fig. 4, S6–13†). Fe–ortho-2-amide achieves the largest observed rate constants (kobs) of all catalysts tested, but exhibits non-linearity at higher phenol concentrations, possibly as a result of catalyst inhibition or local depletion of CO2. Fe–ortho-1-amide exhibits the next highest set of kobs values, followed by Fe–para-2-amide and finally Fe–para-1-amide. Maximum turnover frequencies (TOFmax) in the presence of 100 mM phenol are summarized in Table 1. Likewise, all four catalysts show first-order dependence on CO2 concentration in the presence of excess (500 mM) phenol (Fig. S20†), as well as on catalyst concentration (Fig. S21†). Taken together, in the linear regimes of [PhOH] and [CO2] where secondary phenomena are minimal, all four catalysts follow the rate law where kcat (M–2 s–1) is the intrinsic third-order rate constant. Average values for kcat, determined at several phenol concentrations in the linear regime, are reported in Table 1. TOFmax and kcat values for unfunctionalized Fe-TPP in the presence of 50 mM amide additive are also shown for comparison, demonstrating that ortho pendant amide groups are necessary to observe large enhancements in activity.

where kcat (M–2 s–1) is the intrinsic third-order rate constant. Average values for kcat, determined at several phenol concentrations in the linear regime, are reported in Table 1. TOFmax and kcat values for unfunctionalized Fe-TPP in the presence of 50 mM amide additive are also shown for comparison, demonstrating that ortho pendant amide groups are necessary to observe large enhancements in activity.

Fig. 4. Observed rate constants (s–1) for catalytic CO2 reduction as a function of PhOH concentration for Fe–ortho-1-amide (blue diamonds), Fe–ortho-2-amide (red squares), Fe–para-1-amide (purple upward triangles), and Fe–para-2-amide (orange downward triangles). Conditions: 1 mM catalyst, 0.1 M TBAPF6 in DMF; 0.23 M CO2; scan rate is 100 mV s–1. kobs values were determined by FOWA.

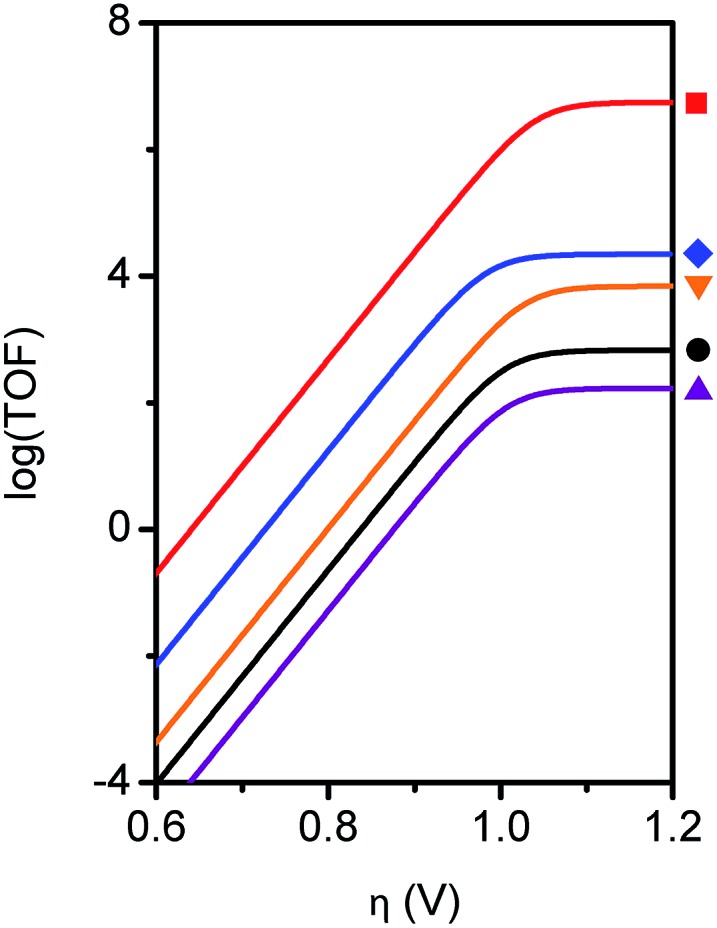

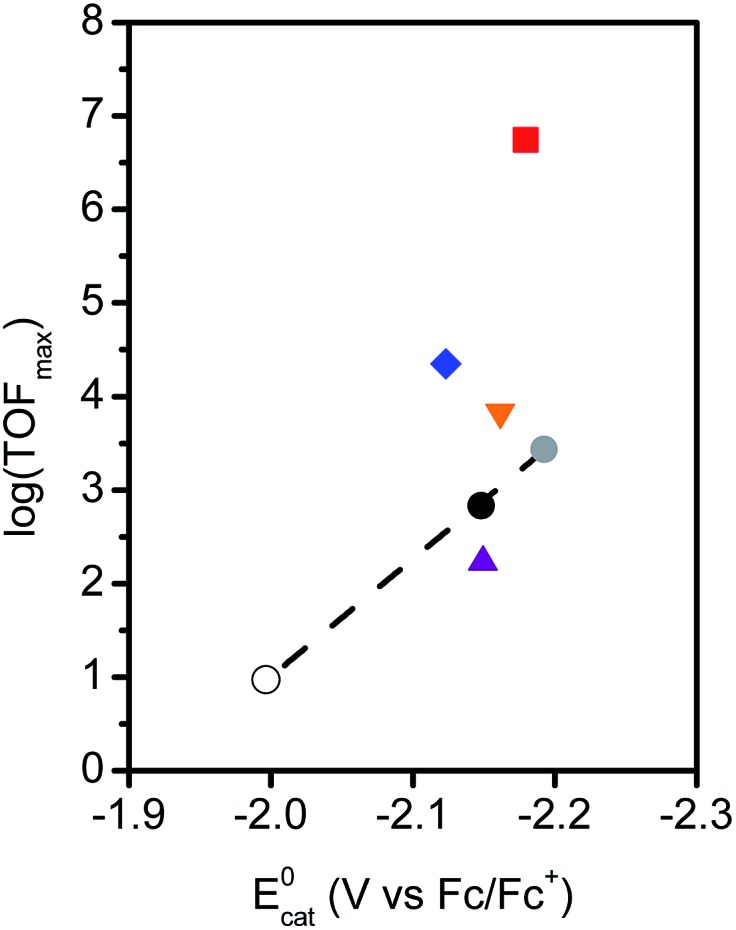

For the purposes of catalyst benchmarking, it is illustrative to examine the log(TOF) vs. overpotential (η) relationships as indicated by a catalytic Tafel plot.61 More effective catalysts operate with higher TOFs at lower overpotentials and are displayed in the upper left portion of such plots. As shown in Fig. 5, Fe–ortho-2-amide exhibits higher TOFs over all overpotential values compared to Fe–ortho-1-amide, which in turn exhibits higher TOFs compared to Fe-TPP and both para-substituted porphyrins. The values at the plateau of such curves represent log(TOFmax), the maximum turnover frequency achievable at large overpotential (when the catalyst is fully present in its reduced state).

Fig. 5. Catalytic Tafel plots for Fe–ortho-1-amide (blue diamond), Fe–ortho-2-amide (red square), Fe–para-1-amide (purple upward triangle), Fe–para-2-amide (orange downward triangle), and Fe-TPP (black circle). Conditions: 0.1 M TBAPF6 in DMF; 0.23 M CO2; 100 mM PhOH; scan rate is 100 mV s–1. TOF = kobs and was determined by FOWA.

The selectivity and stability of the aforementioned catalysts were examined by controlled potential electrolysis (CPE). A solution of catalyst in CO2-saturated DMF electrolyte (0.1 M TBAPF6, 0.5 mM catalyst, 0.5 M phenol as acid source) was electrolyzed at potentials between –2.1 and –2.2 V vs. Fc/Fc+ in a homemade gas-tight electrolysis cell (see ESI† for details). Gas chromatographic measurements of the headspace reveal that all four amide-functionalized catalysts have high selectivity for CO, with faradaic efficiencies (FE) between 74% and 92% (Tables 1, S2†). No hydrogen was observed for any catalyst under these conditions. Representative CPE traces are provided in Fig. S25.†

Though the previous metrics indicate that Fe–ortho-2-amide is a superior catalyst compared to Fe–ortho-1-amide, it is important to stress that the difference in E0cat values between catalysts must be considered when attempting to resolve questions of optimal second-sphere pendant placement. As illustrated previously,62,63 electron withdrawing- or donating substituents on the porphyrin aryl rings modulate E0cat and consequently alter the driving force for electrochemical CO2 reduction. In such cases, a linear scaling relationship between log(TOFmax) and E0cat is observed, where catalysts having more negative E0cat values exhibit larger TOFs. Deviation from this relationship occurs when second-sphere interactions either promote or inhibit catalysis, as has been previously documented for electrostatic effects.64

In order to benchmark the electronic scaling relationship, Fe-TPP and two additional iron porphyrins with no second-sphere influences were investigated: Fe–para-(CF3)4, the iron complex of meso-tetra(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)porphyrin, and Fe–para-(OMe)4, the iron complex of meso-tetra(4-methoxyphenyl)porphyrin. The synthesis and characterization of these two additional complexes are provided in the ESI.† Cyclic voltammograms of Fe–para-(CF3)4 and Fe–para-(OMe)4 in the presence of phenol and CO2 show characteristic responses indicative of CO2 reduction (Fig. S14, S18†). FOWA was applied to determine TOFmax values under conditions identical to those given above for the amide-functionalized porphyrins (Fig. S15, S19†). Controlled potential electrolysis experiments (Fig. S26†) show that CO is also a major product for these two catalysts, with FECO of 70–74% (Table S2†). The similar product selectivity permits meaningful comparisons with the amide-functionalized complexes. The electrochemical parameters for Fe–para-(CF3)4 and Fe–para-(OMe)4 are summarized in Table S1.† Together with Fe-TPP, these two catalysts exhibit the expected linear relationship between log(TOFmax) and E0cat (circles, Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Correlation between log(TOFmax) and E0cat illustrating the through-space interactions that promote catalysis in the case of Fe–ortho-1-amide (blue diamond) and Fe–ortho-2-amide (red square). Porphyrin catalysts with no through-space interactions are shown in black: Fe–para-(CF3)4 (white circle), Fe-TPP (black circle), and Fe–para-(OMe)4 (gray circle). Fe–para-2-amide (orange downward triangle) and Fe–para-1-amide (purple upward triangle) show minimal through-space effects. TOFmax determined by FOWA in the presence of 100 mM phenol and 0.23 M CO2.

To examine the contribution of through-space interactions on catalysis by the ortho- and para-amide-substituted porphyrins, each complex was added to the plot of log(TOFmax) vs. E0cat shown in Fig. 6. Both Fe–ortho-1-amide and Fe–ortho-2-amide lie significantly above the line corresponding to electronic-only effects, confirming that second-sphere interactions enhance the rate of CO2 reduction for both complexes. Fe–ortho-2-amide shows a much larger departure from the electronic correlation line compared to Fe–ortho-1-amide, suggesting that the extent of through-space stabilization of the iron-bound CO2 adduct is larger for the distal ortho isomer than for the proximal congener. In contrast, the log(TOFmax) for Fe–para-2-amide is very slightly higher, and that for Fe–para-1-amide is very slightly lower, than that predicted by the electronic scaling relationship, suggesting that the para-substituted positional isomers do not exhibit notable through-space effects.

In order to gain further insight into the role of the ortho amide pendants in promoting catalysis, we determined the equilibrium constants for CO2 binding, KCO2, based on the potential shift of the formal FeI/0 couple under Ar and CO2. These experiments were performed at fast scan rates (2–10 V s–1) in the absence of an added proton source to prevent subsequent catalytic turnover (Fig. S35†). As shown in Table 2, Fe-TPP and Fe–para-2-amide, which lack the ability to engage in productive through-space interactions, exhibit low KCO2 values (2–4 M–1). In contrast, Fe–ortho-1-amide and Fe–ortho-2-amide exhibit significantly larger KCO2 values (14–17 M–1), indicating that properly positioned amide pendants act to increase the affinity for CO2via hydrogen bonding interactions. Quantum chemical calculations on the Fe–CO2 adducts of both ortho-functionalized complexes reveal differences in the length of the amide-CO2 hydrogen bond (see ESI† for details), with an H–O distance of 1.61 Å for Fe–ortho-1-amide and 1.45 Å for Fe–ortho-2-amide (Fig. S39, S40†). The shorter H-bond distance for the latter complex is in agreement with the larger through-space interaction seen electrochemically (Fig. 6).

Table 2. Summary of equilibrium CO2 binding constants (KCO2), amide pKa values, and kinetic isotope effects (KIE) for the iron porphyrin catalysts.

| Catalyst | K CO2 a (M–1) | Amide pKa | KIE b |

| Fe-TPP | 2.3 | N/A | 1.5–2.5 c |

| Fe–ortho-1-amide | 17.1 | 18.7 ± 0.2 | 1.47 |

| Fe–ortho-2-amide | 14.4 | 19.3 ± 0.1 | 1.77 |

| Fe–para-1-amide | — | 18.8 ± 0.1 | 1.88 |

| Fe–para-2-amide | 3.6 | 18.7 ± 0.5 | 1.84 |

aThe binding constant for Fe–para-1-amide could not be measured but is expected to be between 2–4 M–1.

bKIE values represent the ratio of kH/kD measured using water as the proton source (see ESI for details).

cValues reported for various proton sources, see ref. 65.

The role of proton transfer during catalysis was examined by measuring the pKa values of all four amide pendants, as well as the H/D kinetic isotope effects. The pKa values of all four amide pendants were determined spectrophotometrically (Fig. S36–38†) in DMSO, as shown in Table 2. Importantly, the amide of Fe–ortho-2-amide is less acidic (pKa = 19.3 ± 0.1) than that of Fe–ortho-1-amide (pKa = 18.7 ± 0.2). Thus, the higher catalytic activity of Fe–ortho-2-amide cannot be ascribed simply to a more acidic amide pendant. In addition, kinetic isotope effects for all four positional isomers were measured using H2O or D2O as the proton source (Fig. S20–S27†). Normal primary H/D kinetic isotope effects were observed for all four amide-functionalized catalysts (kH/kD between 1.47 and 1.88, see Table 2), suggesting that proton transfer is involved in the rate-determining step regardless of amide positioning.

These results confirm, unsurprisingly, that second-sphere donors must be located at the ortho-positions of the porphyrin scaffold to exhibit productive interactions with catalytically-relevant intermediates. More interestingly, we show that a distally-located second-sphere amide group is more effective at breaking the electronic scaling relationship for CO2 reduction than the proximal positional isomer due to enhanced hydrogen bond stabilization of the Fe–CO2 intermediate. Differences in pKa of the four amide pendants are minimal, indicating that their position with respect to the iron-bound CO2 is more likely what governs differences in catalytic activity. The primary kinetic isotope effects observed for all four amide-functionalized catalysts are in agreement with those measured with other proton sources65 or for other CO2 reduction catalysts,22 and indicate that proton transfer is involved in the rate-determining step. Given the pKa of the amide pendants, they are expected to act as proton relays in addition to hydrogen bond donors. We therefore conclude that distal ortho positioning allows the pendant to adopt a configuration that is more ideally suited to both hydrogen bond stabilization and proton transfer.

Conclusions

In summary, we investigate the positional dependence of secondary coordination sphere groups on the reactivity of a conserved primary iron porphyrin core for electrochemical CO2 reduction. To this end, four positional isomers were synthesized, varying the location of the second-sphere amide group ortho- and para-, as well as proximal and distal, to the porphyrin plane. Cyclic voltammetry and controlled potential electrolysis were used to fully characterize the electrochemical behaviour of this family of functionalized porphyrins, including kinetic parameters, catalytic Tafel plots, and faradaic efficiencies for the product CO. Studying the correlation between log(TOFmax) and the FeI/0 standard potential, E0cat, reveals that through-space interactions enhance the rate of catalysis in both ortho-functionalized positional isomers, with the distally-located amide exhibiting a more significant enhancement. In contrast, the para-functionalized congeners display no significant through-space effects. These results demonstrate that fine-tuning the location of second-sphere pendants is an effective design strategy for the development of highly-active biomimetic catalysts for CO2 reduction, and by extension, for a wider range of chemical transformations.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank DOE/LBNL Grant 101528-002 for funding this research. C. J. C. is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a CIFAR Senior Fellow. E. M. N. and P. T. S. acknowledge the NSF for graduate research fellowships. S. K. N. thanks the UC Berkeley College of Chemistry for a summer undergraduate research award. We acknowledge the National Institutes of Health for funding the UC Berkeley CheXray X-ray crystallographic facility under the Shared Instrumentation Grant S10-RR027172. We also thank Micah S. Ziegler for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Procedures for synthetic, spectroscopic, and electrochemical experiments. CCDC 1582750. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: 10.1039/c7sc04682k

References

- Appel A. M., Bercaw J. E., Bocarsly A. B., Dobbek H., DuBois D. L., Dupuis M., Ferry J. G., Fujita E., Hille R., Kenis P. J. A., Kerfeld C. A., Morris R. H., Peden C. H. F., Portis A. R., Ragsdale S. W., Rauchfuss T. B., Reek J. N. H., Seefeldt L. C., Thauer R. K., Waldrop G. L. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:6621–6658. doi: 10.1021/cr300463y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson E. E., Kubiak C. P., Sathrum A. J., Smieja J. M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:89–99. doi: 10.1039/b804323j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A. J., Meyer G. J., Fujita E. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:1983–1994. doi: 10.1021/ar9001679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K. H., Hiratsuka K., Sasaki H., Toshima S. Chem. Lett. 1979;8:305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hammouche M., Lexa D., Savéant J. M., Momenteau M. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1988;249:347–351. [Google Scholar]

- Hammouche M., Lexa D., Momenteau M., Saveant J. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:8455–8466. [Google Scholar]

- Bhugun I., Lexa D., Savéant J.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:1769–1776. [Google Scholar]

- Behar D. D., Dhanasekaran T., Neta P., Hosten C. M., Ejeh D., Hambright P., Fujita E. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:2870–2877. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B. J., Eisenberg R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:7361–7363. [Google Scholar]

- Tinnemans A. H. A., Koster T. P. M., Thewissen D. H. M. W., Mackor A. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas. 1984;103:288–295. [Google Scholar]

- Beley M., Collin J.-P., Ruppert R., Sauvage J.-P. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1984:1315–1316. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beley M., Collin J. P., Ruppert R., Sauvage J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:7461–7467. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita E. C., Creutz C., Sutin N., Szalda D. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J., Jia H., Kobiro K., Cabelli D. E., Muckerman J. T., Fujita E. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012;5:9502–9510. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy D. C. M., McCrory C. C. L., Peters J. C. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:4980–4988. doi: 10.1021/ic403122j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawecker J., Lehn J.-M., Ziessel R. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1984:328–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hawecker J., Lehn J.-M., Ziessel R. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1986;69:1990–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan B. P., Meyer T. J. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1984:1244–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Bolinger C. M., Story N., Sullivan B. P., Meyer T. J. Inorg. Chem. 1988;27:4582–4587. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H. T., Tanaka K., Tanaka T. Organometallics. 1987;6:181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bourrez M., Molton F., Chardon-Noblat S., Deronzier A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:9903–9906. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smieja J. M., Benson E. E., Kumar B., Grice K. A., Seu C. S., Miller A. J. M., Mayer J. M., Kubiak C. P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:15646–15650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119863109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson M. D. N., Nguyen A. D., Grice K. A., Moore C. E., Rheingold A. L., Kubiak C. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:5460–5471. doi: 10.1021/ja501252f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater S. W., Wagenknecht J. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:5367–5368. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois D. L., Miedaner A., Haltiwanger R. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:8753–8764. [Google Scholar]

- Kang P., Meyer T. J., Brookhart M. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:3497–3502. [Google Scholar]

- Thoi V. S., Chang C. J. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:6578–6580. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10449g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoi V. S. K., Kornienko N., Margarit C. G., Yang P., Chang C. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:14413–14424. doi: 10.1021/ja4074003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal J., Shaw T. W., Stanton C. J., Majetich G. F., Bocarsly A. B., Schaefer H. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:5152–5155. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal B., Song J., Neese F., Ye S. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015;25:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drennan C. L., Heo J., Sintchak M. D., Schreiter E., Ludden P. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:11973–11978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211429998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeoung J.-H., Dobbek H. Science. 2007;318:1461–1464. doi: 10.1126/science.1148481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W., Hao B., Wei Z., Ferguson D. J., Tallant T., Krzycki J. A., Chan M. K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:9558–9563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800415105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collman J. P., Gagne R. R., Reed C., Halbert T. R., Lang G., Robinson W. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:1427–1439. doi: 10.1021/ja00839a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collman J. P., Zhang X., Wong K., Brauman J. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:6245–6251. [Google Scholar]

- Wuenschell G. E., Tetreau C., Lavalette D., Reed C. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:3346–3355. [Google Scholar]

- Momenteau M., Reed C. A. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:659–698. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. K., Liang Y., Aviles G., Peng S.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:4191–4192. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. J., Chng L. L., Nocera D. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1866–1876. doi: 10.1021/ja028548o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada A., Harata M., Hasegawa K., Jitsukawa K., Masuda H., Mukai M., Kitagawa T., Einaga H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:798–799. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980403)37:6<798::AID-ANIE798>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada A. H., Honda Y., Yamaguchi S., Nagatomo S., Kitagawa T., Jitsukawa K., Masuda H. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:5725–5735. doi: 10.1021/ic0496572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBeth C. E., Golombek A. P., Young V. G., Yang C., Kuczera K., Hendrich M. P., Borovik A. S. Science. 2000;289:938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas R. L. Z., Zart M. K., Mukerjee J., Sorrell T. N., Powell D. R., Borovik A. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15476–15489. doi: 10.1021/ja063935+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook R. L., Borovik A. S. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:3646–3660. doi: 10.1021/ic901550k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook S. A., Borovik A. S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:2407–2414. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berreau L. M., Makowska-Grzyska M. M., Arif A. M. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:2212–2213. doi: 10.1021/ic001190h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowska-Grzyska M. M. J., Jeppson P. C., Allred R. A., Arif A. M., Berreau L. M. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:4872–4887. doi: 10.1021/ic0255609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson E. M., Park Y. J., Fout A. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:17398–17401. doi: 10.1021/ja510615p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. M., Szymczak N. K. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:3373–3377. doi: 10.1039/c5sc00720h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. L., Park Y. J., Matson E. M., Gordon Z., Fout A. R. Science. 2016;354:741–743. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutz S. E., Peters J. C. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:2321–2328. doi: 10.1039/c6sc04805f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M. L., Stewart M. P., Bullock R. M., DuBois M. R., DuBois D. L. Science. 2011;333:863–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1205864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. Y., Smith S. E., Liu T., Dougherty W. G., Hoffert W. A., Kassel W. S., DuBois M. R., DuBois D. L., Bullock R. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:9700–9712. doi: 10.1021/ja400705a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A., Mondal B., Sen P., Dey S., Dey A. Inorg. Chem. 2017;56:1783–1793. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogutan D. K., McGuire R., Nocera D. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9178–9180. doi: 10.1021/ja202138m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C. T. M., Matson B. D., Mayer J. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5444–5447. doi: 10.1021/ja211987f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costentin C., Drouet S., Robert M., Savéant J.-M. Science. 2012;338:90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1224581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapovetsky A., Do T. H., Haiges R., Takase M. K., Marinescu S. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:5765–5768. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S., Sharma B., Pécaut J., Simon P., Fontecave M., Tran P. D., Derat E., Artero V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:3685–3696. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costentin C., Passard G., Robert M., Savéant J.-M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:14990–14994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416697111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costentin C., Drouet S., Robert M., Savéant J.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:11235–11242. doi: 10.1021/ja303560c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcarate I., Costentin C., Robert M., Savéant J.-M. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:28951–28960. [Google Scholar]

- Pegis M. L., McKeown B. A., Kumar N., Lang K., Wasylenko D. J., Zhang X. P., Raugei S., Mayer J. M. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016;2:850–856. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcarate I., Costentin C., Robert M., Savéant J.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:16639–16644. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costentin C., Drouet S., Passard G., Robert M., Savéant J.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:9023–9031. doi: 10.1021/ja4030148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.