Abstract

Context:

Cancer as a life-threatening disease develops a range of existential challenges in persons. These challenges cause the patients to encounter some existential questions and tensions. This study method focuses on a person's experience about them.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to illuminate the meaning of existential challenges in patients with cancer in Iran.

Subjects and Methods:

A hermeneutic phenomenological approach, influenced by the philosophy of Ricoeur, was used to analyze the experiences of 10 Iranian patients with cancer. Data analysis was based on three stages of simple and fast understanding, structural analysis, and comprehensive understanding.

Results:

The present study showed that existential challenges in patients with cancer can be considered as getting out or remaining in the cage of inauthentic self. This theme consists of two subthemes “Being exposed to the light of awareness that revealed the cage of inauthentic self” and “The tension between getting out of the cage or remaining.” First, being exposed to the light of awareness revealed the cage of inauthentic self which subjectively refers to the emergence of existential questions, the past, the fear of future, and the collapse of physical body identity. Second, the tension between getting out of the cage or still staying which is characterized by anger, denial, sense of loneliness, and depression.

Conclusions:

According to the results of this qualitative study, it is possible to form discussion groups with peers or have self-reflective practice teaching groups to reflect patients' questions and existential challenges. In this way, participants can express themselves, share their experiences, challenges, learn, and find the answers.

Keywords: Cancer, existential challenge, Iran, meaning, nursing, phenomenology

INTRODUCTION

The importance of cancer is obvious to everyone in light of the changes in its prevalence worldwide, and its impact on family, economy, and society.[1]

Cancer causes a person to become physically weak so that one cannot tolerate her/his disabilities. In addition, the symptoms and the side effects cause the person to think about his/her death.[2] Thus, in many cultures worldwide, cancer is still associated with the concept of death.[3] Therefore, cancer develops a range of existential challenges in a person.[4] Existential tensions in patients with advanced cancer are even greater than their psychological tensions.[5] As cancer threatens patients' life, patients encounter an existential uncertainty so that they do not know whether they will be alive in the coming moments or not.[2,6] This deep understanding of both being and not being at the same time, causes the patients to repeatedly encounter some existential questions such as why me?, If I am to die, why was I born?, and what is the meaning and purpose of life.[7,8]

In this stage, if the individual fails to find the meaning, he or she will be occupied with existential predicament.[9] The authors use various equivalents for existential tensions such as existential predicament, existential crisis, existential suffering, spiritual suffering, and spiritual pain [10,11,12,13,14] Existential tensions are life experiences with low or no meaning,[9] which lead to a sense of deep separation between the person and himself, others and the world.[6]

Bruce et al.[11] and Bilderman (2005) have shown that the existential crisis refers to the circumstances in which a patient experiences problems such as frustration, feelings of frivolity, meaninglessness, regret and blame, death anxiety, disorder in personal identity and proposes the question “Why me?”[11,14,15] also argues that being aware of mortality (the main characteristic of the existential crisis), the loss of the future and opportunities of life, lead to fear, anxiety, and panic. Disappointment, loneliness, disability, and cognitive crisis are also issues that occur in this crisis.[14,16] Mount considers the existential crisis as a split between the person and the previous reality, which results in a change in the person's attitude and lifestyle.[17] However, despite the fact that there are numerous attempts to define this concept, Boston et al.,[18] Sand and Strang [19] and Strang et al.[20] state that a precise definition has not yet been provided.[18,19,20] Bruce et al.[11] reported that during the existential crisis, patients experience concepts such as groundlessness or, in other words, breaking from within, and then, the concept longing for Ground in a Ground (less) World is proposed. In this stage, the person experiences a feeling of groundlessness, and this propels the person to attempt to achieve an existential stability that prompts him to seek a way to understand what life is.[11]

Although a great deal of research has been done over the last few years on the existential challenges in patients with cancer, there are still many deficiencies in the care of these patients.[21] For providing a better palliative care, a deep understanding of the patients' psychological pain near death is necessary.[22] (Mardani-Hamooleh and Heidari, 2016). Therefore, care providers should receive accurate and rigorous training in this reality.[10,23] Based on Newman and Watson's theory, both the length of time a nurse passes alongside the patient, as well as interviewing and listening to the patient, are parts of holistic nursing care.[24,25] Unfortunately, there is no clear theoretical framework for understanding the nature of existential crisis, and there are not any protocols or therapeutic interventions for relieving these people's pain.[26] According to Henoch and Danielson,[21] there are few qualitative studies in this area.[21] Studies in the field of existential challenges in cancer patients are often quantitative and in our country there is a lack of qualitative research in the field of existential challenges.[27] Phenomenology is one way of studying phenomena within a culture. The methodology seeks to focus on a person's experience, previous understanding and knowledge, which are embedded in culture and religion.[28] Thus, this phenomenological hermeneutic study was conducted to illuminate the meaning of existential challenges in patients' with cancer in Iran.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Aim

The aim of the study was to illuminate the meaning of existential challenges in patients' with cancer in Iran.

Study design

This was a hermeneutic phenomenological study based on Ricoeur approach. The meanings of phenomena cannot be understood if they are not considered through human experiences. When the experience is expressed it can be analyzed as text and considered as the knowledge informants have about that phenomenon.[28] Therefore, open narrative interviews with cancer patients were used to discover through the stories a world that is further exposed to new interpretations and understandings.[29] This method provides an opportunity to combine the philosophy of the meaning of lived experiences with a hermeneutic interpretation of a transcribed interview text. The interpretation can create a deeper understanding of the phenomena, based on dialectical movement between understanding and explanation to a new understanding. In the new understanding, the text is interpreted, based on the researcher's preunderstanding.[30]

Participants and setting

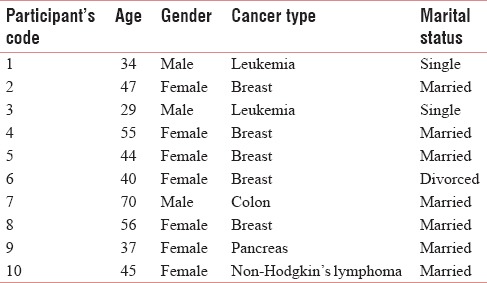

From autumn 2016 to spring 2017, patients who had cancer were interviewed. Patients had referred to three hospitals affiliated with Kerman University of Medical Sciences for undergoing therapy. A purposive sample of participants, who had experience of cancer (leukemia, non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma, colon, pancreas, and breast cancers) participated in the research. They were selected through a chain sampling approach; a key informant recommended one person who in turn, recommended another.[31] On average, the participants had 9 months to 4-years-experience of cancer. The mean age of participants was 45.7 years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristic of participants

Data collection

In-depth individual, semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants in their preferred time and place. The participants were asked to narrate their experiences of challenges experienced during the time they had cancer. Clarifying and encouraging questions were used, such as: “Please, explain more about…” or “Can you provide an example?” The interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by the authors. During the interviews, the researchers tried to strike a balance between listening to the stories told by the participants and keeping the focus of the conversation on the aim of the study. The interviews lasted between 40 and 110 min.

Ethical consideration

This paper is a part of a nursing PhD thesis. The thesis has been approved by the Ethical Committee Center of Kerman University of Medical Sciences (Ethical Code: ir.kmu.rec. 1395.580). The nature of the study was explained to the participants and they were informed that they could withdraw at any time if they so wanted. Confidentiality was guaranteed as no names or facts were to be stated in data or report that enabled anybody, other than the researchers, to identify a single participant. Speaking about their existential challenges and the experiences related to this individual has an emotionally charged nature and may be a painful reminder of various situations. The researchers managed this situation by being attentive and sensitive to the interviewees' emotional reactions. The researchers also gave the participants sufficient time to consider their participation in the study.

Data analysis

The interviews were analyzed using the principles of phenomenological hermeneutics as developed by Ricoeur.[30] The meaning of the translated text was thoroughly checked using several steps. This included going back to the original transcriptions and recordings during the analysis. In the first phase of the analysis, the interviews were read with an open mind to gain a naive understanding of the meaning of cancer patient's experiences about existential challenges. In this phase, there was an attempt to identify an approach for further structural analysis. The whole text was read and divided into “meaning” units. The units were condensed and interpreted against the background of a naive understanding. They were then sorted and all condensed meaning units abstracted to form subthemes and themes. Finally, a comprehensive understanding was formulated; the researchers recontextualized the text.[30,32]

RESULTS

The results section in this study includes three stages of (1) simple and fast understanding, i.e. naïve understanding, (2) structural analysis, and (3) comprehensive understanding.

Naïve understanding

It seems that the meaning of existential challenges in present study may contain some feelings like the guilt of neglecting one's personal health and suppressed anger as the cause of illness. In addition, the fear of death and future, losing the future opportunities, damage to the mental image of the ego, and the physical body are other existential challenges. According to our participant's experiences, they first thought about the past and their sins which led to the disease. Then, they gradually encountered the fear of future and not being alive for their planned future. Finally, by moving through the disease and treatment, they experienced mental and physical damages which led to internal breakdown. All of these may cause uncontrollable emotions such as denial, anger, loneliness, and depression.

Structural analysis

Structural analysis showed that the existential challenges in patients with cancer can be considered as getting out or still staying in the cage of inauthentic self. This theme consists of two subthemes “Being exposed to the light of awareness that revealed the cage of inauthentic self” and “The tension between getting out of the cage or still staying.” The first subtheme refers to the emergence of existential questions, rumination about the past, the fear of future, and the collapse of physical body identity, and the second is characterized by anger, denial, a sense of loneliness, and depression.

Being exposed to the light of awareness that revealed the cage of inauthentic self

According to our participant's experiences, inauthentic self is one that the patient has lived with, for all of his or her lifetime. This kind of self can be considered as inauthentic self. It is characterized by thoughts, feelings, emotions, and the physical body image, which are just illusions and do not really exist. When a person is diagnosed with cancer, it is a sudden shock and it disrupts his daily mental thoughts. Consequently, the person understands of the meaning of life and his life expectancy is disturbed.

According to the experience of cancer patients, due to difficult conditions, the awareness of the existence will arise. Before cancer and facing difficult conditions, the everyday problems of life cause them to be ignorant of existential issues. In fact, cancer is considered as an unusual situation, which is the cause of achieving awareness in these people. This awareness of existence in these people appears in the form of questions like “Who am I?” and “Why have I been born?”

“Before I became ill, I did not understand the meaning of hard conditions. But suddenly I lost this blessing, I lost my health. I was broke from the inside, the internal self dissolved. I felt that all my existence collapsed like a wall and I gradually turned into another person (p3)”.

“I always thought about it. if I am to die, why was I born? (P1).”

Emergence of existential questions causes the participants to spend most of their time thinking about the past and being anxious for the future. Some patients feel guilty after confirming their diagnosis of cancer and blame themselves for not going to the doctor earlier. They always look for a reason to justify their illness. Sometimes, they think that the lifestyle, stress, and life problems are the causes of their illness. Others believed that neglecting their health and diet was a reason for the disease and its development. Some participants thought that their disease is because of their sins. For example, they think that their anger is considered as the main cause of the disease.

“Sometimes I used to go to the bathroom and look at my body. I said to myself: my God, what did I do with this body that caused me to get this illness? (P2).”

“I had a lot of problems with my husband and his family. It really bothered me at that time. I did not say anything to his family but after going back home I would argue with my husband. I continuously hurt myself with these thoughts, and they became cancerous. It was this suppressed anger that appeared in the form of cancer (p6).”

Having a severe and deadly disease such as cancer causes many challenges in the person's life. The meaning of these challenges can be understood in the participants' experiences. According to their experiences, when a person sees himself close to his own death, he should inevitably get along with the new problems of life. They compare themselves with other patients who are in the final stages of the disease and see themselves closer to death. According to the experiences of the patients, they think that there are no other opportunities in their lives. They try to escape from the disease, but they find no way. They think that they have not completed their jobs yet and the future is so ambiguous for them. Thinking about this problem is frightening for them.

“The death of each cancer patient affected me, especially when the type of his or her illness was exactly like mine. I had breast cancer and when Mrs.died because of breast cancer, I was upset for a few days. I went to my room and locked the door. I did not want to talk to anyone. I tried to escape from these thoughts but couldn't.(P4)”

“Once, when I realized the fact, to be honest, I said to myself that everything is finished. its over. I was upset and worried that I had a lot of work I hadn't done yet (p7).”

The ego is formed by considering the body as the self. By the start of the chemotherapy and its side effects, such as hair loss, weakness, and becoming thin, the mental image of the self is disturbed. Since the patients before the cancer are very careful about their physical body and consider their identity as their body, therefore, after physical changes in appearance, they think that the weakness in their body is accompanied by the weakness of their self-existence.

“When I began to lose my hair after taking medicine, I went to the hairdresser and cut it off. Though I had already seen the cases who had lost their hair because of chemotherapy, I didn't think that my hair would go away like that. When I cut my hair, I looked at the mirror. it had become worse. I held the hairdresser's knees and I started crying (p9).”

In addition, since breasts in women are considered as sexual organs and play an important role in the beauty of their appearance, any damage to them is considered as harming the mental image of the self. According to the participants' statements, faced with a different appearance in the family, in front of the husband and in the society and accepting these changes is challenging. Some participants talk about experiencing worries during mastectomy surgery and are anxious as to whether they will be accepted by their husbands after their mastectomy.

“When I was supposed to undergo mastectomy, I was really worried about my appearance. I didn't know if my husband would accept my appearance. I talked to him but he said that “your health is more important. I'll take it as extra flesh that has been taken out“(p4).”

The tension between getting out of the cage or remaining

According to our participant's experiences, when an inner storm occurs in the minds of people as they hear that they have cancer, they experience various levels of deep emotional damage and physical problems. Indeed, these damages cause patients to face their existential beliefs. In this step, usually existential beliefs threaten patients' inauthentic self and cause them to feel uncertainty about their being. Therefore, all aspects of patients' life will be affected by this uncertainty.

All the people experience saddening events in their lives, and this creates deep emotional damage and physical problems and keeps them constantly on the verge of acceptance and denial. At the first moment when the patient is diagnosed with cancer, he or she would have different reactions. Losing physical health seems to be a crisis in life, and people show different psychological responses to it. The patient may not believe they have the disease. He or she begins to deny the disease just like the cancer patient who refused to start chemotherapy. For example, one of the participants says:

“I didn't believe my illness until the chemotherapy started. I thought that the doctor is pulling my leg. When I went for chemotherapy I said to the doctor “I am not sick. I don't have cancer. don't do chemotherapy (p1).”

“For 3 months after the doctors told me that I have stage 3 cancer, I didn't take any treatment. I was very upset. I could not accept it (p10).”

After denial, some patients said that they were angry because of their disease. Patients at this stage are angry with others and even with God. After anger, the person tries to deal with the disease and control the situation. At this stage, they often think that others are responsible for their disease and start to blame them. Many cancer patients ask themselves: “why me? Why should I become ill with cancer? It's not fair”. These people punish themselves or become very aggressive with others.

“Every time I asked myself: 'There are a lot of people who tell lies, a lot of people who commit sins. Why should I be ill from among these people? (P8)”

“I was always angry with God. I said: “God, I lost my whole life, I lost all my wealth, and I lost my money. Now ''m alone with two children. and the cancer” (p6).”

According to the experiences of the participants, the cause of suffering, anger, and negative feelings such as the feeling of inferiority, depression, frustration, etc., is far from their minds. People would be pleased as long as everything is fine and the people do not bother them, and they are completely healthy. However, when they are faced with an unpleasant situation, they become upset and depressed and after denial and anger, they start grieving and mourning. They become upset because they are about to lose their belongings and strength. A feeling of helplessness arises in these patients as a result of this feeling of weakness.

“I did not think about anything in my first chemotherapy. I was just upset. I wasn't crying. I was not looking for the answer to my questions. I just said: I'm going to die. My life is going to end (p7).”

People in this study state that they need someone to talk to tell him or her about their physician and emotional pain. They want somebody to listen to them. After facing cancer, the patient feels lonely and this increases his or her anxiety and stress. The patient recognizes family members, the wife or the husband and the friends as the supports and looks for the empathy of the others. If the wife or the husband can understand his or her partner, the peace will return to the patient. But when the patient is recognized as a patient who just needs physical care, the need for understanding will increase and this might exacerbate the disease. As one of the patients who is a widow expresses:

“When I had terrible pain, I really felt that I needed a companion, I said to myself: I wish my husband was here (crying) (p5).”

Comprehensive understanding

It seems that cancer patients in this study were exposed to the light radiations of awareness. The light radiations that were imprisoned by the cage of inauthentic self or ego. Cancer broke this cage. The cage that had already been shaped by social norms within which they grew up. Existential challenges may mean a tension between getting out of the broken cage or remaining in the cage. Cancer as a boundary situation can be interpreted as a gift from the universe or an authentic failure or hard and heart rending as an inauthentic failure. It is only in the borderlines that the peace disappears, at least for some time, and the person asks: “why am I living at all?” Everything fades away. Values and the goals related to the ego or inauthentic self will become meaningless, and absurdity will appear. The inauthentic self-revealed in the light of cancer is followed by a great many related challenges. Some challenges will arise, and depending on the person's ability to confront the inauthentic self, caused by the cancer, they can be interpreted as existential challenges: challenges related to the past, the fear of an ambiguous future, and disappearing of the physical body, followed by anger, depression, and loneliness.

DISCUSSION

Cancer can be considered as light radiation which reveals the inauthentic self in the person and leads to existential challenges and the disappearance of the ego. Existential philosophers have defined cancer as a borderline. As Jaspers argued, the boundary situation occurs when a person faces situations such as death, feeling guilty, suffering, misfortune, etc., and this causes a person to encounter some paradoxes in his or her life.[33] Heidegger also believes that the situations which disturb the person's life and make the values meaningless are borderline situations.[33,34] According to Jaspers, the borderline situation sometimes allows people to reach the final position, and the final position, from his point of view, is the same as the failure position. The failure means you cannot escape from it because it is your fate. However, the point is that failure can be genuine. In fact, authentic failure must happen spontaneously. It is only in an authentic failure that the person finds himself again, and an authentic dialog is reached between himself and that position.[35] Kierkegaard even considers failure to be a gift from God. In other words, brightness and light are achieved only when it is “broken,” but this “broken” light does not exist unless we consider that “broken” beam as a sign.[36] Heidegger also considers memento more as an authentic value. In fact, he believes that such an authentic life, which is based on the relationship between the persona and the universe, is meaningful. This authenticity has two salient characteristics. The first one is being aware of the fears and response to the call of conscience and the second is the autonomy and concentration. However, inauthenticity refers to the fact that the person has not realized his life.[33] The two salient features of this inauthentic self from Rumi's point of view are neglecting death and sinking in daily routine.[33,37,38,39] In fact, it can be said that one's attitude toward death determines the authenticity or inauthenticity of his or her life.[37]

According to the experiences of the participants, when a person faces cancer, he or she suddenly goes into shock and this disturbs their daily mental thoughts. He or she has already been considering himself or herself as the ego and has been sunk in daily routine. However, the cancer, as an impact, has destroyed this imaginary wall. According to Comprehensive Medical Care, Ventegodt, one of the pioneers of comprehensive medicine, explains that the necessary condition to cure cancer is achieving the real self. He says that you must abandon the efforts, values, goals, and daily routines, which are considered as the inauthentic or imaginary self, in the life before cancer, to face the authentic self.[40,41] About memento mori and facing death, Rumi says that the unreal self is like a shadow or illusionary ghost that has been formed in darkness and ambiguity due to lack of observation and scholarly search.[42]

According to the results of this study, people, following the collapse of this imaginary wall, start looking for the meaning of life and questions such as “Why was I born?” are formed in their minds. Boston et al.,[10] McSherry and Cash,[43] Mackinley [8] and Wise et al.[6] also argued that the existential crisis means losing the meaning and purpose of life and finding new meanings, as well as the desire to answer questions like “Why am I here?,” “What is the purpose of my life?,” and “What happens to me after death [6,8,10,43] Martela and Steger [44] has defined the “meaning” as “the goal and purpose.” He states that one should look for the meaning of his or her life, something beyond the daily routine. Another meaning of the word “meaning” is “value, importance, and credibility.” In this case, the question “Does life have meaning?” means that what is considered as a value in life or the values and credits which are important in everyday life can actually make life meaningful.[44] Ventegodt et al.[45] in his Life Mission Theory states that the nature of human is his purpose of life which the concept of existence is based on. One of the goals that a person is born with is the aspect of protecting life and another one is destructive and evil goals in life.[45] Some patients, according to their own experience, compare themselves with other patients who are in the final stages of the disease and see themselves closer to death, so they become afraid of what is going to happen in the future. They also think about the past and feel guilty. They blame themselves and look for a reason for becoming ill. They see their way of living and even their sins and deeds as the causes of their disease. From Rumi's and Heidegger's views, three nonauthentic qualities are comparing the self with others, hanging on to the past, and fear of the future.[37] Rumi believes that the basic characteristics of life with the nongenuine self are escaping from death and neglecting it and sinking in daily routine, a person who has not been aware of his or her life and has always decided without awareness and thinking about death.[37] Woodward [46] and Mosaffa [42] also state that ideas, values, beliefs, and their way of thinking about themselves are only images that have been implicated in the mind. Fear of death, destroys this imaginary, and mental identity.[42,46] After these values and credits disappear, the person thinks that he or she has not achieved his or her goals yet and he or she is faced with the fear of failing to meet the demands of life.[47] Bruce et al. also state in their study that when people are faced with cancer they feel futility. They also complained about disturbing thoughts such as not traveling and failing to meet the goals ahead.[11] Some of the researchers mentioned that the sense of approaching death is considered as a kind of depression and is related to human psyche.[23] Lichtenthal's study (2009) also distinguishes between the psychological suffering and the existential challenge. In psychological suffering, such as depression, the patient does not have anxiety and proximity to death, but in existential challenges, he finds himself close to death.[5] However, Boston et al.[10] states that we cannot say with certainty that such concepts are existential, psychological, or spiritual challenges because they can be found in each of these areas.[10]

According to what was mentioned, another issue that hurts patients mentally is considering the self as the physical body. In addition, challenges such as hair loss, breast removal, and sexual dysfunction are among these challenges, and a study by Pakseresht et al.[48] and Ussher et al.[41] confirms this [48,49] In this regard, Mako et al.[50] based on the experiences of cancer patients stated that understanding the self and relationship with the body can be seen as a crisis or spiritual suffering.[50] However, Blondeau et al.[51] states that in some studies, the concept of mental image damage has been separated from the existential challenges and is considered as physical suffering.[51] In this regard, we can refer to Goffman's theory called Symbolic Interactionism. According to this theory, in everyday life, the first impression is very important. Appearance, which is visible and appealing to both one's own person and to others, can serve as a mark for interpreting the action.[52] Veblen also states that in the society, the value of objects is measured according to their beauty and this is considered as a credit for people.[53] Therefore, beauty is considered to be a value or credit in societies, which, according to those who became aware of this beauty and its loaned nature, are the greatest devils, and when they are admired, they grow up and become greater so that it would be quite difficult to overcome them. When that magnitude breaks down, these values and credits lose their meaning. According to the theory of panic management, facing death is a threat not only to “the physical self “but also to the” the symbolic self.” Death disturbs the credits and values that have been formed through life and made “the self” and “my being.”[54]

In this study, people suffer from uncontrollable emotions that could be considered to be the side effects of considering the ego as the self. Responses such as denial, anger, depression, and a sense of loneliness after this mental disintegration have occurred to these people according to their experiences. Bruce et al.[11] also, according to the participants' experiences in their study, state that fear, unanswered mental questions, concerns, mental disorientations, and pain are the main problems of cancer patients.[11] They mention that this experience is not similar to any previous experience and none of the compatibility mechanisms that they previously used are effective for accepting this issue.[11] Pynn [55] also states that cancer is followed by fear and anxiety,[55] and Zebrack et al.,[56] Henoch and Danielson,[21] and Yang et al.[14] state that cancer can lead to serious mental issues, including awareness of finitude and fear of facing death, dissolution of the future, loss of meaning, fear, anxiety, stress, phobia, panic, despair, disappointment, loneliness, and powerlessness [14,21,55,56,57]

According to the results of this study, most people after receiving their diagnosis, show reactions such as sadness, crying, anger, aggression, and even suicide. They also ask themselves “Why me?” “Why should I get cancer?” and they think that this is not fair. Bruce et al.[11] and Mackinley [8] also state that frustration, anger and aggression, breaking the beliefs, forming questions such as “Why me?” Why did I become ill, I have always tried to be a good person? Are among the challenges of cancer patients.[8,11] However, in Bilderman's study, patients have stated that they have never asked “why did I become ill?” They believed that there is not something called “me,” and they felt free because they believed that they had reached “no self.”[15]

Having formed these questions in the mind of the patients and not getting the answer, they will suffer from depression and a sense of loneliness, and they welcome grief and sadness. According the profound interviews conducted by Sand and Strang [19] with cancer patients, it has also been shown that following existential loneliness, both the patient and his or her family need to be in touch with others and talk to them.[19]

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study showed that one of the most important existential challenges in patients with cancer was being exposed to the light of awareness that revealed the cage of inauthentic self and the tension between getting out of the cage or remaining. Seeking answers to mental questions and anxiety are among the side-effects of staying in the cage of inauthentic self. In addition to the issues mentioned, it is important to note that the results of the present study are in line with the majority of studies in this field. Therefore, it can be concluded that these are not culture bound, and the existential challenges in different countries are experienced in a similar way, and the only difference is the language of expression. According to the results of this study and what the participants say in their experiences, it is important to pay attention to such needs in the patients with cancer and to provide appropriate care for them. However, the main problem is that there is no institute in Kerman providing palliative care to cancer patients to present these results and provide psychological counseling in the field of existential challenges that are fundamental issues for patients with cancer who suffer from them. In addition, according to the results of this qualitative study, it is possible to form discussion groups with peers or have self-reflective practice learning groups to reflect on the questions or existential challenges. In this way, participants can express themselves and share their experiences and challenges and learn and find the answers. In addition, there is a need for emphasis and further studies on the ego and its manifestation before death.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biniaz RB, Goudarzi M, Sahmani M, Moghaddasi MH, Dehghanifard A, Vatanmakanian M, et al. Challenges in the treatment of Iranian patients with leukemia in comparison with developed countries from the perspective of specialists. J Paramed Sci. 2014;5:4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlsson M, Friberg F, Wallengren C, Ohlén J. Meanings of existential uncertainty and certainty for people diagnosed with cancer and receiving palliative treatment: A life-world phenomenological study. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13:28. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamanzadeh V, Rahmani A, Valizadeh L, Ferguson C, Hassankhani H, Nikanfar AR, et al. The taboo of cancer: The experiences of cancer disclosure by iranian patients, their family members and physicians. Psychooncology. 2013;22:396–402. doi: 10.1002/pon.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mutalik S. Psycho Oncol. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. Clinical Psycho-Oncology: An International Perspective; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenthal WG, Nilsson M, Zhang B, Trice ED, Kissane DW, Breitbart W, et al. Do rates of mental disorders and existential distress among advanced stage cancer patients increase as death approaches? Psychooncology. 2009;18:50–61. doi: 10.1002/pon.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wise TN, Biondi M, Costantini A. Psycho-Oncology. Washington DC, London, England: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay LL, Schulz ML. All is Well: Heal Your Body with Medicine, Affirmations, and Intuition. Amazon.de Hay House, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackinley RE. Aging, Spirituality and Palliative Care. New York and London: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Spek N, Vos J, van Uden-Kraan CF, Breitbart W, Tollenaar RA, Cuijpers P, et al. Meaning making in cancer survivors: A focus group study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boston P, Bruce A, Schreiber R. Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: An integrated literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:604–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruce A, Schreiber R, Petrovskaya O, Boston P. Longing for ground in a ground (less) world: A qualitative inquiry of existential suffering. BMC Nurs. 2011;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coyle N. The existential slap – A crisis of disclosure. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2004;10:520. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.11.17130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner KA. Spontaneous/radical remission of cancer: Transpersonal results from a grounded theory study. Int J Transpersonal Stud. 2014;33:7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang W, Staps T, Hijmans E. Existential crisis and the awareness of dying: The role of meaning and spirituality. Omega (Westport) 2010;61:53–69. doi: 10.2190/OM.61.1.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blinderman CD, Cherny NI. Existential issues do not necessarily result in existential suffering: Lessons from cancer patients in israel. Palliat Med. 2005;19:371–80. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1038oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown R, McKenna HP. Conceptual analysis of loneliness in dying patients. Int J Palliat Nurs. 1999;5:90–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mount BM, Flanders E. Existential suffering and the determinants of healing. Eur J Palliat Care. 2003;10:40–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boston PH, Mount BM. The caregiver's perspective on existential and spiritual distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sand L, Strang P. Existential loneliness in a palliative home care setting. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1376–87. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strang P, Strang S, Hultborn R, Arnér S. Existential pain – An entity, a provocation, or a challenge? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:241–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henoch I, Danielson E. Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: An integrative literature review. Psychooncology. 2009;18:225–36. doi: 10.1002/pon.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kashfi A. Philosophical analysis of psychological suffering patients on the verge of death and Its place in medical ethics. Iran J Diabetes Lipid. 2007;8:45–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams BR. Dying young, dying poor: A sociological examination of existential suffering among low-socioeconomic status patients. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:27–37. doi: 10.1089/109662104322737223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman MA, Sime AM, Corcoran-Perry SA. The focus of the discipline of nursing. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1991;14:1–6. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson J. Nursing: Human Science and Human Care: A Theory of Nursing. Vol. 5. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breitbart W, Gibson C, Poppito SR, Berg A. Psychotherapeutic interventions at the end of life: A focus on meaning and spirituality. Focus. 2007;5:451–8. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinclair S, Pereira J, Raffin S. A thematic review of the spirituality literature within palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:464–79. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris DA. Doing research drawing on the philosophy of existential hermeneutic phenomenology. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15:267–9. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516000377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barton SS. Narrative inquiry: Locating aboriginal epistemology in a relational methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:519–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricoeur P. Interpretation Theory: Discourse and the Surplus of Meaning. Fort worth: Texas Christian University press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research, Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks: Wiley Online Library; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindseth A, Norberg A. A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18:145–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McManus D. Heidegger. Authenticity and the Self: Themes from Division Two of Being and Time. London And New York: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wrathall M. In: Autonomy, authenticity, and the self. Heidegger, Authenticity and the Self: Themes from Division Two of Being and Time. Mcmanus D, editor. London, New York: Routledge; 2015. pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanghellini G, Fuchs T. One Century of Karl Jaspers' General Psychopathology. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Söderquist KB. A Companion to Kierkegaard. Blackwell companions to philosophy. Wiley Blackwell: 2015. Kierkegaard and existentialism; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akbarzadeh F, Shahnazari J, Dehbashi M. Comparative analysis of death and its relationship with the meaning of life from the perspective of Rumi and Heidegger. Elahiate Tatbighi. 2014;5:11, 20. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azadeh M. Philosophy and the Meaning of Life. Tehran: Negahe Maaser; 2011. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shepherd RJ. Why Heidegger did not travel: Existential angst, authenticity, and tourist experiences. Ann Tour Res. 2015;52:60–71. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ventegodt S, Morad M, Hyam E, Merrick J. Clinical holistic medicine: Induction of spontaneous remission of cancer by recovery of the human character and the purpose of life (the life mission) ScientificWorldJournal. 2004;4:362–77. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2004.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ventegodt S, Solheim E, Saunte ME, Morad M, Kandel I, Merrick J, et al. Clinical holistic medicine: Metastatic cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2004;4:913–35. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2004.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosafa MJ. Man in Bondage Thought. Vol. 1. Tehran: Nafas; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McSherry W, Cash K. The language of spirituality: An emerging taxonomy. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41:151–61. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(03)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martela F, Steger MF. The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J Posit Psychol. 2016;11:531–45. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ventegodt S, Andersen NJ, Merrick J. The life mission theory V. Theory of the anti-self (the shadow) or the evil side of man. ScientificWorldJournal. 2003;3:1302–13. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2003.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodward T. Conscious Being: Awakening to Your True Nature. Bloomington: Balboa Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosafa MJ. Ba Pire Balkh. Vol. 2. Tehran, Iran: Nafas; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pakseresht S, Monfared A, Ghanbari A, Atrkar Roshan Z, Rahimi A. Investigating body image and the related factors among women with breast cancer at educational and therapeutic hospitals in Rasht. Mod Care Sci Q Birjand Nurs Midwifery Fac. 2014;11:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E. Women's sexuality after cancer: A qualitative analysis of sexual changes and renegotiation. Women Ther. 2014;37:205–21. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mako C, Galek K, Poppito SR. Spiritual pain among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1106–13. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blondeau D, Roy L, Dumont S, Godin G, Martineau I. Physicians' and pharmacists' attitudes toward the use of sedation at the end of life: Influence of prognosis and type of suffering. J Palliat Care. 2005;21:238–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goffman E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, 1959. Garden City, NY: New York: Scribner's; 2002. p. 131.p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Etemadi Fard SM, Amani M. Sociological study of the motivation of women to tend to cosmetic surgeries. Womens Res J. 2013;4:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leary MR, Tangney JP. Handbook of Self and Identity. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pynn CT. One Man's Life-changing Diagnosis: Navigating the Realities of Prostate Cancer. United states of America: Demos Medical Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zebrack BJ, Corbett V, Embry L, Aguilar C, Meeske KA, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychological distress and unsatisfied need for psychosocial support in adolescent and young adult cancer patients during the first year following diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2014;23:1267–75. doi: 10.1002/pon.3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blanc C, Coluccia F, L'Haridon F, Torres M, Ortiz-Berrocal M, Stahl E, et al. The cuticle mutant eca2 modifies the plant defense responses to biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens and herbivory insects. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2017:1–57. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-17-0181-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]