Abstract

Background:

Palliative care is an approach that focuses on improving a patient's quality of life. This research aimed to develop a path model of the relationships between the variables of nursing care (information, emotional support, technical support, and palliative care), patient coping, family support, patient spirituality, and patient comfort expressed through physical and emotional mediators.

Method:

This cross-sectional study involved 308 breast cancer patients from 3 referral hospitals in Jakarta, Indonesia. A structural equation model with Kolcaba's theory was used to develop a theoretical model estimating the path or relationships between the key variables.

Results:

The results showed that palliative care significantly improved breast cancer patient comfort by reducing anxiety and depression. Furthermore, the study demonstrated a significant positive relationship between spirituality and emotional well-being.

Conclusion:

Spirituality-focused palliative care is fundamentally importance for breast cancer patients. Nurses play an essential role in providing spirituality-focused palliative care to promote comfort in breast cancer patients in Indonesia.

Keywords: Breast cancer, comfort, palliative care, spiritual

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care aims to assist patients in relieving pain and other distressing symptoms while preparing for a peaceful dying process using constructive coping techniques with treatment. Nevertheless, palliative care is likely to be misinterpreted as end-of-life care. Consequently, it has not been integrated into the oncology practice.[1] As a matter of fact, palliative care is appropriate for patients of any age and at any stage of a serious illness. Moreover, it can be provided simultaneously with curative treatment.[1]

Cancer patients rarely receive palliative care in a timely manner. Ideally, palliative care is initiated at the time that the patient is admitted to the hospital and newly diagnosed with cancer and is continued throughout the medication and/or intensive treatment through the end-of-life stage. There is evidence that palliative care may reduce morbidity, mortality, and the costs associated with cancer treatment.[1,2] Thus, this study used observed palliative care as a latent variable of nursing care to develop the comfort theoretical model.

The other latent variables encompassed individual resources, such as coping, family support, and spiritual equity. Coping is an individual's ability to deal with the physical and psychological problems associated with the breast cancer process. Family support is a fundamental component in palliative care due to its roles in increasing a patient's motivation and progress. Finally, spirituality provides strength and promotes a patient's comfort concurrently. Indonesia has notable with its religious and cultural diversity; therefore, spirituality should be an essential aspect of palliative care in Indonesia.

A model was developed from Kolcaba's comfort theory because it is suitable to Indonesian context. In addition, we assumed that palliative care, along with the latent variables of nursing care and individual resources, would affect patient comfort through physical and emotional mediators. The results of this study are expected and can contribute to both nursing science and the development of palliative nursing care in Indonesia.

METHODS

We received ethical approval for this study which employed a cross-sectional method. The research involved 308 patients with two-stage cancer or above and no central nervous system metastases. They were admitted to either the outpatient or inpatient departments of three different referral hospitals in Jakarta, Indonesia. This study aimed to develop a theoretical model that statistically fits the data and was able to examine the factors affecting a cancer patient's comfort (nursing care, patient characteristics, coping, family support, and spirituality) with physical and emotional mediators.[3] We performed structural equation modeling (SEM) using the Mplus Version 7.4 Base Program Single-User License (Muthén & Muthén, 3463 Stoner Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90066).

We used five standardized instruments along with other two additional instruments that were created and validated in this study. We obtained permission to use the following standardized instruments: Brief COPE Inventory to measure the patient's coping ability, Family Support Scale, Spiritual Perspective Scale (SPS), breast symptom scale, and Depression Anxiety Stress Scale. The two instruments developed in this study were the patient perception measurement about palliative care and Comfort Assessment Breast Cancer Instrument. All of the instruments were tested for construct validity using the Mplus software.

RESULTS

Data analysis univariate

The results of this study showed the respondents' characteristics and their interrelationships. We used the Kolcaba's theory approach while developing the theoretical model. From 308 respondents, 114 (37%) were older adults (45–59 years old) and 85 (27.6%) were middle-aged adults (35–44 years old). Over three-quarters (81.5%) or 251 of the total respondents were from outpatient departments. Most of the respondents were married (n = 265, 86%), Muslims (n = 268, 87%), obtained senior high school degrees (n = 124, 40.3%), and bachelor's degrees (n = 87, 28.2%). This study showed that 225 (73.1%) of the patients were unemployed or housewives, and 83.4% had household incomes below the prevailing regional minimum wage or <3,350,000 IDR. Nearly one-half (45.1%) or 139 of the respondents were diagnosed with Stage 3 breast cancer. The main caregivers were the respondents' spouses (n = 146, 47.4%) and their children (n = 96, 31.2%).

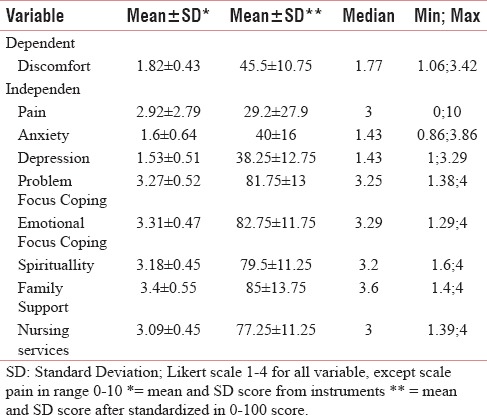

Table 1 presents medium score for discomfort: 45.5 ± 10.75, low score and high standard deviation for level pain: 29.2 ± 27.9, and low score for level anxiety and depression: 40 ± 16 and 38.25 ± 12.75. Otherwise, individual sources (coping, spirituality, and family support) and nursing services attain high score.

Table 1.

Mean and median for discomfort, level of pain, anxiety, depression, problem focus coping, emotional focus coping, spirituallity' patient, and perception's patient about family support and nursing services (n=308)

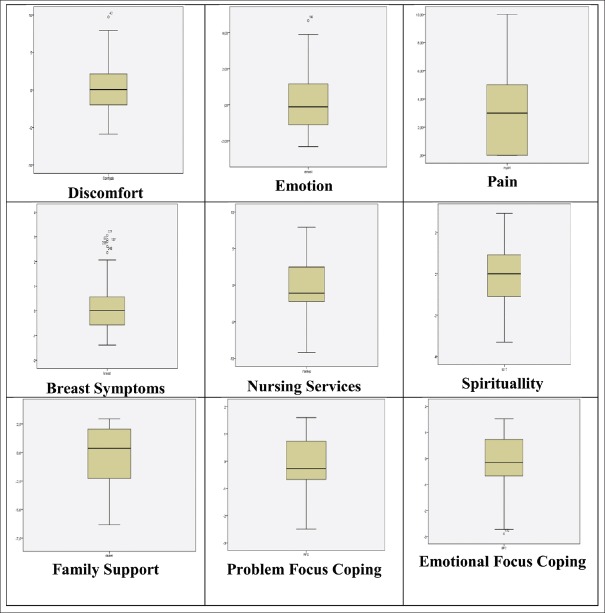

Figure 1 demonstrates a normal distribution for discomfort, breast symptoms, and spirituality (line in middle of the box). Normality of data affects multivariate analysis using SEM.

Figure 1.

Box plot dependent variable (discomfort) and independent variable (emotion, breast symptoms, nursing services, spirituality, family support, problem-focused coping, and emotion-focused coping)

Analysis multivariate by structural equation modeling

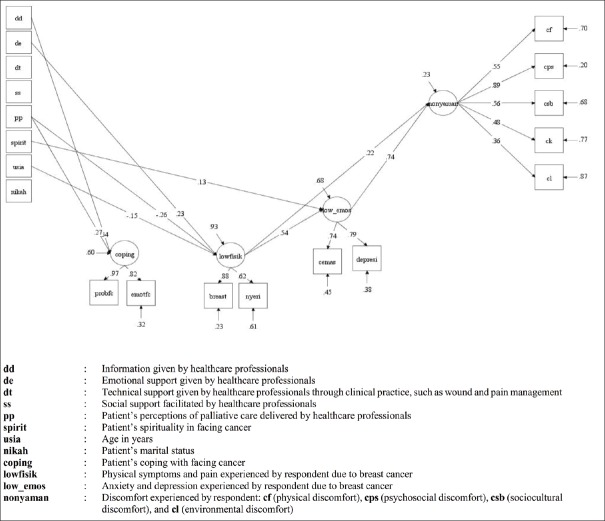

The Mplus analysis of the comfort theoretical model demonstrated a negative, significant correlation between palliative care and the discomfort expressed through both physical and emotional mediators. The results indicated that an increase in palliative care would significantly decrease a patient's discomfort as expressed through emotional and physical mediators. Conversely, the discomfort expressed through the emotional mediators and spirituality was significantly positively correlated. These results implied that the increase in discomfort experienced by a breast cancer patient would also increase their spirituality. The SEM of the relationships between the variables in this study is depicted in Figure 2, description of which is as follows:

Figure 2.

Structural equation modeling of the relationships between the variables

Information support and palliative care affect coping

Palliative care and emotional support affect discomfort through mediator physical and emotional condition

Spirituality affects discomfort through mediator emotional condition

Age affects discomfort through mediator physical condition

Physical condition affects emotional condition.

The result of analysis using SEM Bayesian showed a fit model. Then, from Chi-square analysis using df 143 P = 0.000; RMSEA 0.061, Prob. RMSEA ≤0.05 was 0.060 and Cumulative Fit Index (CFI) 0.917. Prob. RMSEA ≤0.05 over from 0.05 and CFI almost 1, proved that this model fit or there was no difference between hipothetic theory and real condition in breast cancer patient in Indonesia.

DISCUSSION

Univariate analysis

Breasts are secondary female sexual organ. Breasts play an important role as part of the female reproductive system. Disorders that occur in the breast can affect physically and emotionally to woman. The result of this research shows medium score for discomfort: 45.5 ± 10.75, low score and high standard deviation for level pain: 29.2 ± 27.9, and average score for level anxiety and depression: 40 ± 16 and 38.25 ± 12.75. Otherwise, individual sources (coping, spirituality, and family support) and nursing services gain a high score. According to data of this research, they depict discomfort in breast cancer patients in Indonesia and include to middle category with high individual sources (coping, spirituality, and family support) and nursing services. This perceived discomfort is not extremely high because the patients have good coping, spirituality, and family support. In addition, the nurse's perception of nursing service is also quite good.

The discomfort which has been felt by breast cancer patients in Indonesia is generally reduced with a variety of complementary therapies and nursing. Effective tactile therapy, massage, and fixation to overcome these discomforts can be applied by nurses to help patients deal with these discomfort issues.[4,5,6,7] Other evidence-based practice results show that acupuncture, massages with aromatherapy, reflection, hypnotherapy, kinesiology, meditation, music, naturopathy, osteopathy, shiatsu, and yoga can help breast cancer patients.[8]

Disturbances in physical conditions may affect the emotional state.[9] Pain associated with stress is supported by the results of Sibille et al. study which explains chronic pain acts as a physical and psychosocial stressor that causes faster aging cells characterized by shortening of leukocyte telomere length.[10] Other researchers added pain related to the stress and mood of women who experienced it and can affect the depression and healing of it.[11]

Treatment services not only focus on the patient itself but also must be attentive to family members of patients. Thus, family members can provide optimal support in cancer patients. The results showed family support in either category with an average score of 3.4 (Likert 1–4). The approach in the palliative care system is to involve family support, especially the husband to care for the patient at home.[12] Home care treatment with the support and good knowledge of family members will be more effective and result better health outcomes in breast cancer patients than hospitalized. While at home, the patient is more comfort and still able to interact utterly with all members of his family. Women who are diagnosed with breast cancer and receive treatment to survive often experience trauma and unpleasant experiences. This traumatic event can be overcome with social support including family.[13]

Treatment services with an average score of 3.09 (Likert 1–4) indicate that providing care services are good enough, but these are still general. Patients need more care services to improve the quality of life. Palliative care is an appropriate service. However, people are still reluctant to use palliative care because of the mistake of defining that palliative care is a dying treatment.[14,15]

Palliative care should be given since patients are declared cancerous so that the quality of life of patients and families can increase.[16,17] Palliative care is an approach to improve the quality of life of patients and families to face life-threatening disease problems. Palliative care means alleviating pain and other symptoms of distress, respecting life and death as normal process, not intending to accelerate or delay death, integrating psychological and spiritual aspects, offering support systems to help the patient's daily life to the end of his life, offering support systems to help family coping during sick patients in their grief, using team approach, and improving quality of life.[18]

The results showed the level of spirituality of patients in both categories, i.e. with a score of 3.18 (Likert scale 1–4), and the majority of respondents are Muslims. Researchers used the SPS instrument to measure the patient's spirituality. SPS measures two dimensions of how often spiritual behavior practicing and how much spiritual degree a person in searching for meaning in life. A person's life is more meaningful if he gives more.[19] Multiple giving is a patient's spiritual needs that should be facilitated. Giving is not just a gift of goods or things, but beyond of it, like affection and attention. Breast cancer patients in Indonesia are mostly female housewives who have children and husbands. By giving affection and attention to family, friends, and relatives, it can lead to the fulfillment of patient's spiritual needs.

In the results of this univariate test, researchers also conducted that a test of normality on all variables has been used, both dependent and independent variables. Normality test is done to see the reason why a model cannot properly fit. Abnormal data may affect a model to be unsuitable. Normality test results in Figure 1 show normality on comfort, breast symptoms, and spiritual variables while emotional variables, pain, nursing service, family support, problem-focused coping, and emotion-focused coping are not normally distributed.

Multivariate analysis

Kolcaba stated that nurses should be able to assess a patient's comfort needs, identify intervening (covariate) variables (such as the demographic factors), provide nursing care, and help a patient to manage their key individual resources (such as coping, family support, and spirituality).[20,21,22] She also shed light on nursing care to promote patient comfort. Nurses, according to Kolcaba, need to meet a patient's basic needs and deliver specific nursing care that is unique for each patient to improve the patient's comfort. Accordingly, palliative care is both important and appropriate for improving a patient's comfort.

Palliative care is an approach that focuses on improving the quality of life for both the patient and their family while facing life-threatening disease and problems related. Its primary purposes are to relieve pain and other distressing symptoms, to assert life, and to consider dying as a normal process, while neither hastening nor delaying death. It integrates both the psychological and spiritual dimensions of care. In addition, it aims to offer a support system for a patient until the end of their life as well as for the family members trying to cope with the patient's illness and grief. Palliative care uses a multidisciplinary team approach to optimize the quality of life.[18]

Religion as a set of spiritual beliefs and practices plays an essential role in Indonesia, which has the largest Muslim population on the globe. As the main religion in the country, Islam teaches its believers to maintain their relationships with God (habluminallah) as well as among humankind (habluminannas). Therefore, spirituality may greatly influence a patient's perception of discomfort and their illness. Thus, we assessed the patients' spirituality using SPS. It measured two main aspects: the frequency of spiritual practices and the degree of spiritual beliefs to find the meaning of life.

Our findings revealed a significant positive relationship (P = 0.05; r = 0.098) between spirituality and patient discomfort through low emotional mediators [Figure 2]. This result indicated that those respondents who drew closer to God were more likely to have greater emotional well-being. On the contrary, those who distanced themselves from God were more likely to have a lesser state of emotional well-being. Therefore, it is important for nurses to facilitate patients in elevating their emotional well-being through worship and other spiritual practices.

There was ample evidence showing that spirituality could enhance a cancer patient's quality of life. Several studies have demonstrated significant relationships between spiritual well-being and the physical, emotional, and functional dimensions of breast cancer.[23] In addition, some studies have shown that a nurse's knowledge pertaining to a patient's spirituality significantly affected the coping ability and quality of life among breast cancer survivors.[24] Other studies have presented the significant effects of an integrated psychospiritual and transformational program to improve the physical, emotional, and functional well-being of cancer patients.[25]

Spirituality has become a unique and vital need for Indonesian society. Their beliefs regarding death and the afterlife greatly affect their views and attitudes toward death. To prepare for the afterlife, they need to draw closer to God by “walking in obedience.” Nonetheless, their ill-health may impede their ability to worship; therefore, personal assistance is heavily importance in assisting patients to meet their spiritual needs.

CONCLUSION

Our comfort theoretical modeling study suggested that palliative care affected patient discomfort through physical and emotional mediators, whereas spirituality affected patient discomfort through emotional mediators. Hence, our research implied the positive effects of palliative care in the improvement of patient comfort. Currently, palliative care in Indonesia is limited or unavailable and frequently misconstrued as end-of-life care. This study showed that spirituality-focused palliative care is the key to promote comfort among breast cancer patients in Indonesia.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors would like to thank PITTA Grant No. 374/UN2.R3.1/HKP.05.00/2017, Universitas Indonesia, for their financial support.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, Basch EM, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocque GB, Cleary JF. Palliative care reduces morbidity and mortality in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:80–9. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. United States of America: SAGE Publication, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanaki Z, Matourypour P, Gholami R, Zare Z, Mehrzad V, Dehghan M, et al. Therapeutic touch for nausea in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: Composing a treatment. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;22:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung BY, Xu Y. Developing a rehabilitation model of breast cancer patients through literature review and hospital rehabilitation programs. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2008;2:55–67. doi: 10.1016/S1976-1317(08)60029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zerwekh JV. Nursing Care at the End of Life Palliative Care for Patients. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company; 2006. p. 472. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolcaba K, Dowd T, Steiner R, Mitzel A. Efficacy of hand massage for enhancing the comfort of hospice patients. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2004;6:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucey R. Breast Cancer Nursing Care and Management. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2011. Compelementary and alternative therapies; pp. 282–308. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ullrich PM, Turner JA, Ciol M, Berger R. Stress is associated with subsequent pain and disability among men with nonbacterial prostatitis/pelvic pain. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:112–8. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibille KT, Langaee T, Burkley B, Gong Y, Glover TL, King C, et al. Chronic pain, perceived stress, and cellular aging: An exploratory study. Mol Pain. 2012;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis MC, Thummala K, Zautra AJ. Stress-related clinical pain and mood in women with chronic pain: Moderating effects of depression and positive mood induction. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9583-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta A, Cohen SR, Chan LS. Palliative care: A need for a family systems approach. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:235–43. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber AS. Examining the Relationship between Female Breast Cancer Survivor's Diagnosis Factors, Perceived Social Support, Internal Control, and Quality of Life. University of Cincinnati; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nickolich MS, El-Jawahri A, Temel JS, LeBlanc TW. In Meeting Library ASC University. 2016. Discussing the Evidence for Upstream Palliative Care in Improving Outcomes in Advanced Cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beernaert K, Deliens L, Pardon K, Van den Block L, Devroey D, Chambaere K, et al. What are physicians' reasons for not referring people with life-limiting illnesses to specialist palliative care services? A nationwide survey. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parikh RB, Kirch RA, Smith TJ, Temel JS. Early specialty palliative care – Translating data in oncology into practice. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2347–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1305469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Tosteson T, Li Z, et al. Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: Outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1446–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/.

- 19.Huda NC. Peristiwa kecil dengan inspirasi besar. In: Hamid N, editor. Hidup Bermakna Dengan Memberi. 1st ed. Surabaya: Penerbit Hikmah Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolcaba K. Comfort Theory and Practice: A Vision for Holictic Health Care and Research. New York: Springer Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lydon JR. Physical Health, Psychological Distress, and Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: A Stress and Coping Model. Indianapolis, Indiana: Purdue University; 2008. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.purdue.edu/policies/pages/teach_res_outreach/c_22.html . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira I. Comfort measures: A concept analysis. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2013;27:95–114. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.27.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan PD, Gaston-Johansson F, Mock V. Spiritual well-being, religious coping, and the quality of life of african american breast cancer treatment: A pilot study. ABNF J. 2006;17:73–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okumakpeyi P, Georges CA, Nickitas D. Women of Faith: Adaptation of African American Women Breast Cancer Survivors. University of New York; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garlick MA, Wall K, Koopman C, Shechtman N. Physical, Psychological, Spiritual, and Posttraumatic Growth Experiences of Women with Breast Cancer Participating in a Psychospiritual Integration and Transformatin Course. Institute of Transpersonal Psychology. 2009 [Google Scholar]