Abstract

Severe spinal cord injury (SCI) damages descending motor and serotonin (5-HT) fiber projections leading to paralysis and serotonin depletion. 5-HT receptors (5-HTRs) subsequently upregulate following 5-HT fiber degeneration, and dendritic density decreases indicative of atrophy. 5-HT pharmacotherapy or exercise can improve locomotor behavior after SCI. One might expect that 5-HT pharmacotherapy acts on upregulated spinal 5-HTRs to enhance function, and that exercise alone can influence dendritic atrophy. In the current study, we assessed locomotor recovery and spinal proteins influenced by SCI and therapy. 5-HT, 5-HT2AR, 5-HT1AR, and dendritic densities were quantified both early (1 week) and late (9 weeks) after SCI, and also following therapeutic interventions (5-HT pharmacotherapy, bike therapy, or a combination). Interestingly, chronic 5-HT pharmacotherapy largely normalized spinal 5-HTR upregulation following injury. Improvement in locomotor behavior was not correlated to 5-HTR density. These results support the hypothesis that chronic 5-HT pharmacotherapy can mediate recovery following SCI, despite acting on downregulated spinal 5-HTRs. We next assessed spinal dendritic plasticity and its potential role in locomotor recovery. Single therapies did not normalize the loss of dendritic density after SCI. Groups displaying significantly atrophied dendritic processes were rarely able to achieve weight supported open-field locomotion. Only a combination of 5-HT pharmacotherapy and bike therapy enabled significant open-field weigh-supported stepping, mediated in part by restoring spinal dendritic density. These results support the use of combined therapies to synergistically impact multiple markers of spinal plasticity and improve motor recovery.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, serotonin, dendrites, pharmacology, locomotion

Introduction

Severe spinal cord injury (SCI) damages descending serotonin (5-HT) projections (Bowker et al., 1981; Skagerberg and Bjorklund, 1985) reducing serotonin levels in the spinal cord (Hadjiconstantinou et al., 1984), contributing to the loss of locomotor function below the level of the lesion. Subsequent 5-HT receptor (5-HTR) upregulation occurs caudal to the SCI in regions associated with hindlimb function (e.g. 5-HT1AR and 5-HT2AR) (Kong et al., 2011 & 2010; Otoshi et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2007). This upregulation has been suggested to play a role in pharmacologically mediated hindlimb locomotor function (Nothias et al 2005; Kao et al, 2006; Dugan and Shumsky, 2015). Furthermore, SCI also damages descending motor control pathways. Following SCI, the caudal spinal circuitry is deprived of supraspinal input promoting paralysis, dendritic retraction, and dendritic atrophy (Byers et al., 2012; Little et al. 2009, Zhang et al., 2000; Gazula et al., 2004). Therefore, 5-HTRs and dendritic processes are involved in locomotor function and are potential targets for therapeutic interventions.

Both 5-HT pharmacotherapy and exercise therapy can affect 5-HTRs and dendritic processes in the spinal cord following injury, potentially promoting plasticity. 5-HTR agonists, given acutely or chronically after injury, have been shown to improve locomotor function across many studies (Landry and Guertin, 2004; Landry et al., 2006; Ung et al., 2008; Nothias et al., 2005; Antri et al., 2002, 2003, 2005; Courtine et al., 2009; Musienko et al., 2011). Exercise therapy is also utilized to improve function after SCI (Fu et al., 2016; Detloff et al. 2014). Specifically, bike exercise therapy has been shown to induce plasticity above the level of the lesion, in part, by enhancing BDNF levels (Graziano et al., 2013). Below the level of the injury, bike exercise therapy also results in reduced spasticity (De Mello et al., 2004; Phadke et al., 2009), reduced rate of bone density loss (Lauer et al., 2011), and reduced lower limb blood pooling (Phillips et al., 1998). Combining 5-HT pharmacotherapy and bike exercise therapy may further enhance recovery and potentially spinal plasticity, compared to either therapy alone.

Further gains in recovery have been realized when 5-HT pharmacology is combined with exercise or training, and these gains are in part facilitated by neural plasticity above the level of the lesion (Ganzer et al., 2013, Foffani et al., 2016; Ganzer et al., 2016; Manohar et al., 2017; van den Brand et al., 2012). There is evidence that 5-HT pharmacotherapy and exercise treatments may act synergistically to enhance plasticity (Mattson et al., 2004). And it is possible that these synergistic effects occur throughout the entire neuraxis, including below the level of the lesion. Furthermore, there is little understanding of how these chronic treatments may promote spinal plasticity to facilitate locomotor recovery, either administered separately or as a combination therapy.

In the current study, we assessed locomotor recovery and spinal proteins indicative of plasticity that are influenced by SCI and therapy. 5-HT, 5-HT2AR, 5-HT1AR, and dendritic densities were quantified both early (1 week) and late (9 weeks) after SCI, and also following therapeutic interventions (5-HT pharmacotherapy, bike therapy, or a combination). Interestingly, chronic 5-HT pharmacotherapy largely normalized spinal 5-HTR upregulation following injury. Improvement in locomotor behavior was not correlated to 5-HTR density. We next assessed spinal dendritic plasticity and its potential role in locomotor recovery. Single therapies did not normalize the loss of dendritic density after SCI. Groups displaying atrophied dendritic processes were rarely able to achieve weight supported open-field locomotion. Only a combination therapy of 5-HT pharmacotherapy and bike therapy enabled significant open-field weigh-supported stepping, mediated in part by restoring spinal dendritic density. These results support the use of combined therapies to synergistically impact multiple markers of spinal plasticity and improve motor recovery.

Materials & Methods

Experimental Design

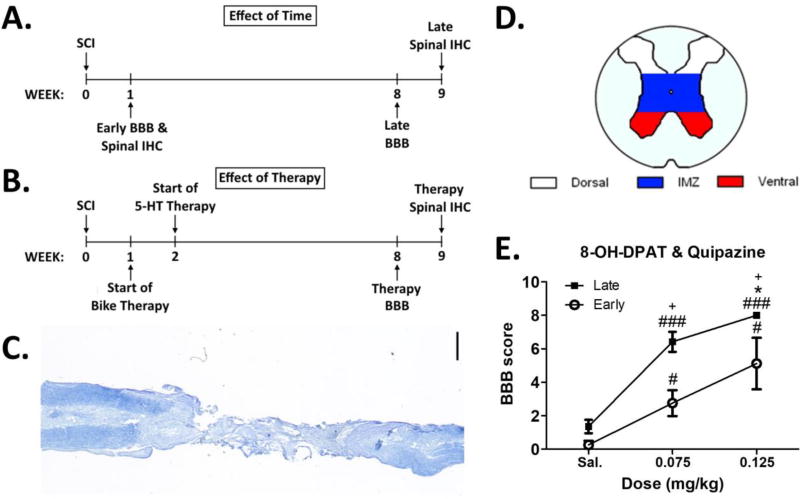

All procedures performed were approved by the Drexel University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250–300 g were used for all experiments (N=41). A subset of rats received a complete spinal transection at T8 / T9 (N=37). We initially tested responses to acute doses of 5-HTR agonists to determine an optimal combination dose that promotes locomotor output (BBB score) without significant side effects (hindlimb tremor and serotonin syndrome measures) (N=11). We next performed 2 sets of studies (Fig. 1A, 1B). Our first study examined the effect of time after SCI alone on locomotor recovery, spinal 5-HTR densities (5-HT1AR and 5-HT2AR), and spinal dendritic (microtubule associate protein 2 or MAP2) plasticity (same animals from acute dose response experiment, N=11). Our second study examined the effect of therapy after SCI on locomotor recovery, spinal 5-HTR densities, and spinal dendritic plasticity (N=26). Here we used chronic 5-HT pharmacology and / or exercise therapy as therapeutic interventions. A single set of uninjured animals (Naïve, N=4) served as tissue for spinal protein assessments for both the effect of time and the effect of therapy studies.

Figure 1. Experimental Timelines, Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Lesion, and Acute Dose Response Curve.

Experimental timelines for the effect of time (A) and effect of therapy (B) studies (IHC = immunohistochemistry). C. Exemplar photomicrograph of a completely transected spinal cord (Nissl and myelin stain; scale bar = 1 mm). D. Color coded schematic of spinal gray matter regions of interest used during 5-HT and MAP2 protein immunostaining assessments. E. Acute dose response on BBB score using a saline (Sal.), 0.075 mg/kg, or 0.125 mg/kg combination dose of the 5-HTR agonists quipazine and 8-OH-DPAT (Late N=7; Early N=4). Within group differences: ### different from Sal. at p<0.001, # different from Sal. at p<0.05; * different from 0.075 mg/kg at p<0.05. Across group differences: + different from Early at same dose at p<0.025. Data displayed is mean ± S.E.M.

Common Method

Spinal Transection Procedure & Animal Care

Similar to our previous studies (Ganzer et al. 2013; Ganzer et al., 2016; Foffani et al., 2016; Manohar et al., 2017), rats received a complete mid-thoracic transection at spinal level T8 / T9. Briefly, animals were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and 2-liters of oxygen and maintained at 2–3% isoflurane with 1-liter oxygen for the duration of the surgery. A laminectomy at the T8 / 9 level was performed to expose the spinal cord. A #10 scalpel blade was used to open the dura and pia mater and #11 scalpel blade was used to make the complete transection of the spinal cord. A fine-tipped microaspiration device was then used to remove 2 – 3 mm of spinal cord. A collagen matrix, Vitrogen (Cohesion Technology; Encinitas, CA), was injected into the site of the spinal transection. Following surgery, animals were given an intramuscular injection of the antibiotic Pen-G and 5 ml of lactated ringer subcutaneously before returning to their home cages.

Animals were housed 2 per cage with highly absorbent Alpha-Dri bedding (Shepherd Specialty Papers Inc. Kalamazoo, MI), and cages were kept on warm water blankets. Animals were housed under a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00) with ad libitum access to food and water. Bladder care was given 3 times daily for 2 weeks or until bladder control was regained. If there was any sign of infection, subcutaneous injections of Baytril (0.06 mg/kg) were given twice a day for 7 days.

Drugs

Quipazine (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) and 8-OH-DPAT (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) were dissolved in sterile saline and administered at a volume of 1 ml/kg i.p. & s.c., respectively. Importantly, all 5-HT agonist injection concentrations for a given experimental group are detailed below in the methods. Acute dose response curve experiments utilized a 0.075 and 0.125 mg/kg 5-HT agonist dose to identify an effective agonist concentration. The effect of time and therapy experiments utilized a 0.125 mg/kg 5-HT agonist dose. For all ‘on-drug’ behavioral testing, agonists were administered 5 minutes before the assessment began.

Open Field Locomotor Scoring

BBB scoring in the open field was used to test behavioral recovery (Basso et al., 1995). Spontaneous hindlimb motor activity was evaluated for 4 min in a spherical enclosure (minor diameter = 2.5 ft.; major diameter = 3 ft.) and scored by two trained observers with an inter-rater reliability ≥ 95%, similar to our previous studies (Ganzer et al., 2013; Ganzer et al., 2016; Foffani et al., 2016; Manohar et al., 2017). BBB scores of 8 or below correspond to various degrees of locomotor-like movements that do not include weight support. BBB scores of 9 or above (to a maximum of 21) indicate some degree of hindquarter weight support starting in stance and progressing to weight-supported stepping.

Acute Dose Response Test

Acute Dose Response Curves

An initial test was performed to determine an optimal 5-HTR agonist combination dose that promoted locomotor output without significant side effects. An acute dose response curve was performed by comparing behavioral responses after an initial injection of saline to a low dose (0.075 mg/kg each) and high dose (0.125 mg/kg each) combination of quipazine and 8-OH-DPAT during weeks 1 (Early, N=4) and 8 (Late, N=7) post-SCI. Animals first received the initial injection of saline (Sal.), followed by the low dose combination of drug and ending with the high dose combination of drug. Each injection was separated by a 24 hour washout period. BBB score, hindlimb tremor and caudal serotonin syndrome scores were assessed after each injection. Results of these tests were used to determine drug dose in the effect of time and effect of therapy studies.

Hindlimb Tremor

Myoclonus (tremor) can be elicited by hindlimb palpation following SCI. The presence of hindlimb tremors was determined by blinded experimenters during the behavioral tests and hindlimb palpation on the plantar surface of the hindlimbs (Kao et al., 2006). Tremors were rated on a 4 point scale [0 = no tremor, 1 = mild (detectable on palpation), 2 = moderate (visually noticeable but does not interfere with function), 3 = intense (interferes with function)].

Caudal Serotonin Syndrome

Depletion of serotonin followed by administration of serotonergic agents has been shown to elicit a group of stereotypies referred to as “the serotonin syndrome” (Martin, 1996). This consists of a constellation of motor behaviors expressed caudal to the injury including hindlimb spasms and curvature of the tail. Animals were observed in the home cage after drug administration and rated on a 4 point scale [0 = none, 1 = mild (1–2 bouts of short duration), 2 = moderate (1–2 bouts of long duration or 3–5 bouts of short duration), 3 = severe (3 or more bouts of long duration)] for each element of the syndrome which were then added together for the final score (Kao et al., 2006).

Effect of Time Study

Our first study examined the effect of time after SCI on locomotor recovery, spinal 5-HTR densities, and spinal dendritic plasticity (Fig. 1A). We used the same Early (N=4) and Late (N=7) animals to assess locomotor recovery (BBB scoring) and spinal protein densities. BBB scoring was performed after administration of high dose (0.125 mg/kg each) combination of quipazine and 8-OH-DPAT at the respective time-point (Fig. 1A). Early and Late animals were sacrificed during weeks 1 and 9 post-SCI, respectively, at least 48 hours after drug administration for tissue collection and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (see below for spinal protein IHC details), and compared to protein densities in tissue harvested from Naïve animals (uninjured, N=4).

Effect of Therapy Study

Our second study examined the effect of therapy after SCI on locomotor recovery, spinal 5-HTR densities, and spinal dendritic plasticity (Fig. 1B). These measures were evaluated during weeks 8 and 9 post-SCI in three spinally transected groups receiving: 1) sham pharmacotherapy and exercise therapy (Bike, N=9), 2) 5-HT pharmacotherapy and sham exercise therapy (5-HT, N=8) and 3) 5-HT pharmacotherapy and exercise therapy (5-HT+Bike, N=9) (see below for therapy administration details). Animals here were sacrificed during week 9 post-SCI at least 48 hours after drug administration, for tissue collection and IHC (see below for spinal protein IHC details), and compared to protein densities in tissue harvested from the same Naïve animals used for the effect of time study.

Exercise Therapy Administration

Starting one week after SCI, Bike and 5-HT+Bike animals received passive bicycling exercise using a custom built motor-driven cycling apparatus (Fig. 1B; Houle et al., 1999; Graziano et al., 2013). Rats were suspended horizontally with their feet secured to the pedals. Cycling speed was maintained at 45 revolutions/min and each exercise bout consisted of two 30-min exercise periods with a 10-min rest period in between. Exercise was administered three times a week (Dugan, 2010) from 1–8 weeks post-SCI (on Mondays, Wednesdays & Fridays). Animals in the 5-HT group were placed on bicycles at the same time periods, but the pedals did not move.

Chronic Drug Administration

Chronic pharmacotherapy was administered 5 days a week (Monday – Friday) from 2–8 weeks post-SCI in the 5-HT and 5-HT+Bike groups (Fig. 1B; drug was administered before exercise in the 5-HT+Bike group). Doses of drug consisted of a combination of the 5-HTR agonists quipazine and 8-OH-DPAT at 0.125 mg/kg each. Animals in the Bike group were given injections of saline.

Tissue Preparation and Spinal Protein Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Perfusion & Tissue Preparation

All animals were sacrificed with Euthasol, perfused transcardially with buffered saline (50 mL), followed by buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4, 500 mL). The spinal cord was then removed and post-fixed in the same buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (for a duration of 12 hours) and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose (for a duration of 36 hours). The spinal cord was removed with spinal roots for anatomical reference. Spinal cord tissue was frozen in Shandon M-1 Embedding Matrix compound (Thermo Scientific), sectioned horizontally at 40µm thickness and slide mounted for staining. The caudal spinal segments assessed (T12-L1) contain the rhythm generating thoracolumbar spinal gray matter (Kjaerulff and Kiehn 1996; Kremer and Lev-Tov 1997). Alternating sections were stained for the presence of 5-HT, 5-HT2AR, 5-HT1AR and MAP2 using avidin-biotin IHC (see below) or Nissl and Myelin to confirm a complete SCI lesion (Fig. 1C).

IHC Controls and Staining Specificity

All protein staining experiments were run with tissue from multiple groups to control for inter-experiment variability. The antibodies used here were quality control tested by the manufacturer to confirm antibody specificity using standard immunohistochemical techniques (5-HT antibody: cat. # 20080, Immunostar; 5-HT1AR antibody: cat. # 24504, Immunostar; 5-HT2AR antibody: cat. # 24288, Immunostar; MAP2 antibody: cat. # M1406, Sigma). In addition, all protein staining experiments here were performed with 3 IHC staining controls to ensure proper antibody performance (IHC staining controls: no primary antibody application, no secondary antibody application, and no primary or secondary antibody application). All controls failed to stain the respective target antigen as expected.

5-HT IHC

Sections of spinal cord tissue were stained for the presence of 5-HT using the following incubations: 1) 0.3% H2O2 & 50% ethanol in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) for 30 mins, 2) PBS rinse, 3) 10% normal goat serum (NGS) and 0.2% Triton in PBS (blocking solution) for 1 hour, 4) polyclonal rabbit anti-5-HT primary antibody (Immunostar) diluted 1:80,000 in PBS containing 2% NGS and 0.2% Triton incubated overnight at room temperature, 5) PBS rinse, 6) biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno Inc.) diluted 1:200 in PBS containing 2% NGS incubated for 2 hours, 7) PBS rinse, 8) Elite ABC reagent (Vector Labs) for 2 hours, 9) PBS rinse, 10) 0.05 M Tris-HCl rinse and 11) 3-3’ diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Sigma) for 20 minutes.

5-HT2AR IHC

Sections of spinal cord tissue were stained for the presence of 5-HT2AR using the following incubations: 1) 0.3% H2O2 & 50% ethanol in PBS for 30 mins, 2) PBS rinse, 3) 5% NGS and 0.1% Triton in PBS (blocking solution) for 1 hour, 4) polyclonal rabbit anti-5-HT2AR primary antibody (Immunostar; antigen corresponding amino acids 22–41 of rat 5-HT2AR) diluted 1:200 in PBS containing 5% NGS and 0.1% Triton incubated for 64 hours at 4°C, 5) PBS rinse, 6) biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno Inc.) diluted 1:200 in PBS containing 2% NGS incubated for 2 hours, 7) PBS rinse, 8) Elite ABC reagent (Vector Labs) for 2 hours, 9) PBS rinse, 10) 0.05 M Tris-HCl rinse and 11)3-3’ diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Sigma) for 50 minutes.

5-HT1AR IHC

Sections of spinal cord tissue were stained for the presence of 5-HT1AR using the following incubations: 1) 0.3% H2O2 & 50% ethanol in PBS for 30 mins, 2) PBS rinse, 3) 2% NGS and 0.2% Triton in PBS (blocking solution) for 1 hour, 4) polyclonal rabbit anti-5-HT1AR primary antibody (Immunostar; recognizes the amino acids 294–312 on the third intracellular loop of rat 5-HT1AR) diluted 1:300 in PBS containing 2% NGS and 0.2% Triton incubated overnight at room temperature, 5) PBS rinse, 6) biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno Inc.) diluted 1:200 in PBS containing 2% NGS for 2 hours, 7) PBS rinse, 8) Elite ABC reagent (Vector Labs) for 2 hours, 9) PBS rinse, 10) 0.05 M Tris-HCl rinse and 11) 3-3’ diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Sigma) for 50 minutes.

MAP2 IHC

Sections of spinal cord tissue were stained for the presence of MAP2 using the following incubations: 1) 0.3% H2O2 & 50% ethanol in PBS for 30 mins, 2) PBS rinse, 3) 2% normal horse serum (NHS) and 0.1% Triton in PBS (blocking solution) for 1 hour, 4) monoclonal mouse anti-MAP2 primary antibody (Sigma; clone AP20; recognizes only high molecular weight forms (MAP2a +2b) and is insensitive to phosphorylation state) diluted 1:500 in PBS containing 2% NHS and 0.1% Triton incubated for 48 hours at 4°, 5) PBS rinse, 6) biotinylated horse anti-mouse secondary antibody (Vector Labs) diluted 1:200 in PBS containing 2% NHS for 2 hours, 7) PBS rinse, 8) Elite ABC reagent (Vector Labs) for 2 hours, 9) PBS rinse, 10) 0.05 M Tris-HCl rinse and 11) 3-3’ diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Sigma) for 20 minutes.

Microscopy & Quantification of Immunohistochemical Stains

All immunostained slides were next dehydrated in a series of alcohol washes and coverslipped using DPX mounting medium (Sigma; St. Louis, MO). Photomicrographs of the 5-HT, 5-HT2AR, 5-HT1AR and MAP2 immunostains were taken across all groups (N=4 for all groups). Using adjacent Nissl and Myelin stained sections, photomicrographs were taken from the rhythm generating T12-L1 segments (Kjaerulff and Kiehn 1996; Kremer and Lev-Tov 1997) across the following spinal gray matter regions of interest (ROIs): 1) Dorsal (Rexed lamina I–VI), 2) Intermediate Zone (IMZ; Rexed lamina VII & X) and 3) Ventral (Rexed lamina VIII & IX) (Fig. 1D). 4–6 photomicrographs were taken from each spinal ROI in each animal. 8-bit gray-scale photomicrographs were taken using a 20× (for the 5-HT, 5-HT2AR and 5-HT1AR immunostains) or 100× (for the MAP2 immunostain) objective. Images were processed in Image J (NIH). Only spinal gray matter was selected for image analysis for all immunostains. MAP2 is primarily found in the somatodendritic region of neurons (Harada et al., 2002). Immunoreactive somata were excluded manually during MAP2 image processing similar to previous study (Adkins-Muir & Jones, 2003) in Image J using custom drawn ROIs. This was done to ensure that only dendritic processes contributed to the MAP2 dendritic density quantification. Background values were calculated and subtracted within images. A threshold value was then chosen for a given immunostain so that only immunopositive elements of the spinal gray matter were selected for image analysis similar to previous studies (Kao et al., 2006; Kong et al., 2010). This threshold value was kept constant for all images across all groups within a given immunostain. The number of pixels occupied by immunolabeled structures within the spinal gray matter was measured. This was then divided by the total amount of pixels in the selected spinal gray ROI to obtain Density (percent of immunopositive pixels).

Data Analysis and Statistics

Normality tests were performed for each analysis to determine if parametric or nonparametric statistics should be used. For IHC data, each density measure from a single animal was counted as an independent sample. All statistical tests were performed in SPSS v18 (IBM). Unless Bonferroni corrections are noted, an alpha level of 0.05 was accepted for significance.

Effects in the acute dose response curve test on BBB, HL tremor and caudal serotonin syndrome scores were evaluated using a two-way repeated measures ANOVAs. The first factor was Time with two levels: Early and Late. The second factor was Dose with three levels: Sal., 0.075 mg/kg, 0.125 mg/kg. Dunnett’s post-hoc test was used to determine differences in behavioral scores between dose. Bonferroni corrected post-hoc t-tests were used to determine differences in behavioral scores between weeks for specific doses (alpha level = 0.025).

Effect of time on BBB score was evaluated using a Mann-Whitney U test. Effect of therapy on BBB score was evaluated using a one-way ANOVA. The factor was Therapy Group with three levels: Bike, 5-HT and 5-HT+Bike. BBB scores of 8 or lower correspond to non-weight supported locomotor behaviors (NWS BBB), whereas BBB scores of 9 and above correspond to weight supported locomotor behaviors (WS BBB). For each therapy group, the ratio of NWS BBB scores to WS BBB scores was calculated. Effect of therapy on the proportion of WS and NWS BBB scores was assessed using Bonferroni corrected two-proportions tests (alpha level = 0.025).

Effects of time and therapy on 5-HT, 5-HT2AR and 5-HT1AR protein densities were each evaluated using separate one-way ANOVAs for the given protein across spinal gray matter ROIs. For the effect of time, the factor for each spinal gray matter ROI protein density assessment was Group with three levels: Naive, Early, and Late. For the effect of therapy, the factor for each spinal ROI protein density assessment was Group with four levels: Naive, Bike, 5-HT, and 5- HT+Bike. Differences between group were determined using Tukey post-hoc tests. Finally, effects of time and therapy on MAP2 dendrite density were each evaluated separately using oneway ANOVAs to assess their impact on anatomical neuronal plasticity (Azmitia et al., 1995; Ramos et al., 2004; Harada et al., 2002). The Group factors and post-hoc tests for effect of time and therapy on MAP2 were identical to those used for 5-HT protein analyses.

Results

Identifying an Optimal Dose of a 5-HTR Agonist Combination

5-HT pharmacology can potentially induce side effects such as hindlimb tremor and serotonin syndrome that can interfere with function following SCI (Kao et al., 2006; Martin, 1996). Therefore, we first utilized an acute dose response curve to identify an optimal combination dose of the 5-HTR agonists quipazine and 8-OH-DPAT that enhanced open-field locomotor behavior without significant side effects. We measured BBB, hindlimb (HL) tremor and caudal 5-HT syndrome scores in response to an injection of saline, 0.075 mg/kg or 0.125 mg/kg 5-HTR combination dose in Early (week 1 post-SCI) and Late (week 8 post-SCI) animals (Fig. 1E). Not surprisingly, there was an effect of dose (F(2,18) = 59.1, p < 0.001). Both the 0.075 mg/kg and 0.125 mg/kg acute dose produced a significant increase in BBB score compared to saline in the Early and Late groups (Fig. 1E). Moreover, in Late animals the 0.125 mg/kg dose produced significantly higher BBB scores compared to the 0.075 mg/kg dose (Fig. 1E). There was a mild increase of HL tremor scores at the 0.125 mg/kg dose compared to saline in Late animals (p<0.05, data not shown; F(2,12) = 13.8, p < 0.001). There were no significant effects on any other side effect measures at any other dose across groups (caudal 5-HT syndrome, no significant difference (NSD): F(2,12) = 2.5, p = 0.121). Therefore, the 0.125 mg/kg combination dose of quipazine and 8-OH-DPAT promotes a significant increase in BBB score without deleterious side effects or hindlimb tremors that interfere with behavioral outcome and was used in the subsequent studies.

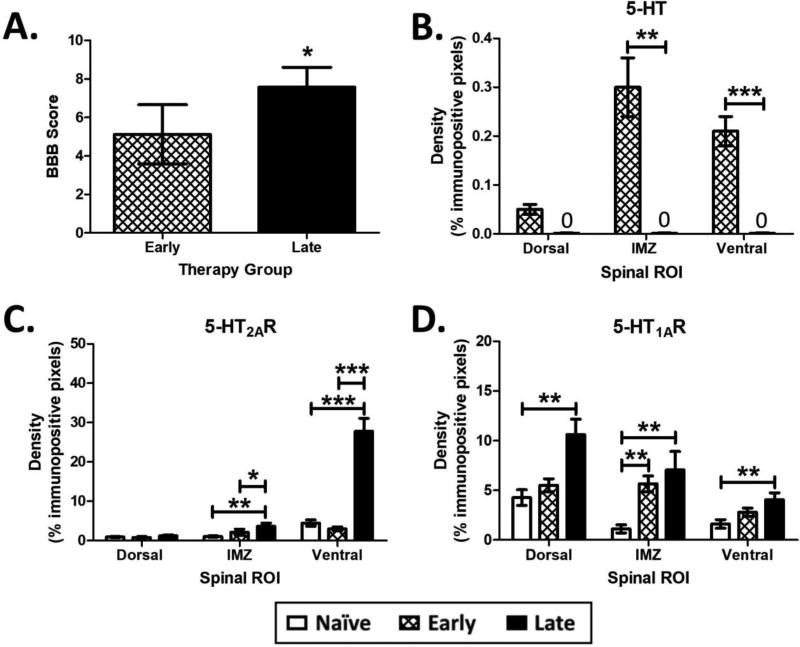

Effect of Time on Locomotor Output and Spinal 5-HT Protein Densities

Interestingly, Late animals achieved significantly higher BBB scores compared to Early animals at both acute doses (data repeated from acute dose response curve; Fig. 2A). However, neither group achieved a weight-supported (WS) BBB score. 5-HT fiber degeneration was not complete in Early animals (week 1 post-SCI; Fig. 2B), in agreement with previous studies on the time course of 5-HT fiber degeneration following SCI (Hadjiconstantinou et al., 1984; Kong et al., 2011). However, as expected all 5-HT fibers had degenerated in Late animals (week 9 post-SCI; Fig. 2B). There were also differences in the 5-HTR distribution in both Early and Late animals.

Figure 2. Effect of Time on Locomotor Output and Spinal 5-HT Protein Densities.

A. Late animals achieved significantly higher BBB scores compared to Early animals when receiving a challenge dose of 5-HTR agonists (Late N=7; Early N=4). Results are from a Mann-Whitney U test. B. 5-HT fiber degeneration below the level of the SCI is not complete in Early animals. Results are from are from independent samples t-tests. C. Spinal IMZ and Ventral 5-HT2AR receptor densities caudal to the SCI are upregulated in Late animals compared to Early and Naïve. D. Spinal 5-HT1AR densities caudal to the SCI are upregulated in Late (in the Dorsal, IMZ and Ventral gray) and Early (in the IMZ) animals compared to Naïve. N=4 for all groups in B, C and D. Results in C and D are from separate one-way ANOVAs. * different at p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Data displayed is mean ± S.E.M.

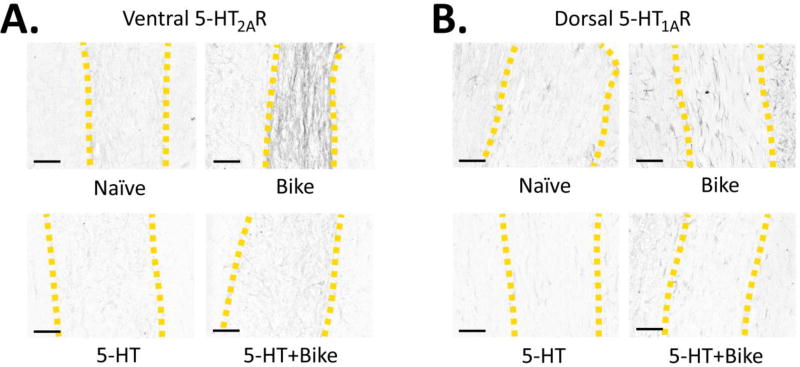

There was no change in Early animal 5-HT2AR expression compared to Naïve (Fig. 2C). Early animals displayed a rather circumscribed upregulation of 5-HT1AR expression in the intermediate zone of the spinal cord compared to Naïve (Fig. 2D), providing evidence that spinal 5-HTRs can upregulate shortly after SCI. Late animals displayed more extensive 5-HTR changes. There was an upregulation of 5-HT2AR expression in both the IMZ and Ventral zones compared to Naïve and Early animals (Fig. 2C; Dorsal (NSD): F(2,54) = 0.7, p = 0.485; IMZ: F(2, 54) = 3.8, p = 0.029; Ventral: F(2,51) = 37.8, p < 0.001) (Ventral exemplar pictures in Fig. 3A). The significant increase of Ventral 5-HT2AR density, in contrast to Dorsal, may reflect its predominant functional role in the ventral horn. Late animals also displayed a significant upregulation of 5-HT1AR across all 3 zones of the cord compared to Naïve animals (Fig. 2D; Dorsal: F(2,60) = 10.2, p < 0.001; IMZ: F(2, 53) = 7, p = 0.004; Ventral: F(2,57) = 4.7, p = 0.012) (Dorsal exemplar pictures in Fig. 3B). There was no correlation between 5-HT2AR or 5-HT1AR expression and BBB score for Early and Late animals (data not shown), likely due to the modest gains in behavioral recovery. Therefore, 5-HT2AR and 5-HT1AR expression is upregulated several weeks after SCI. The incomplete 5-HT fiber degeneration in Early animals may prevent the more widespread and significant upregulation of 5-HT2A and 5-HT1ARs seen in Late animals.

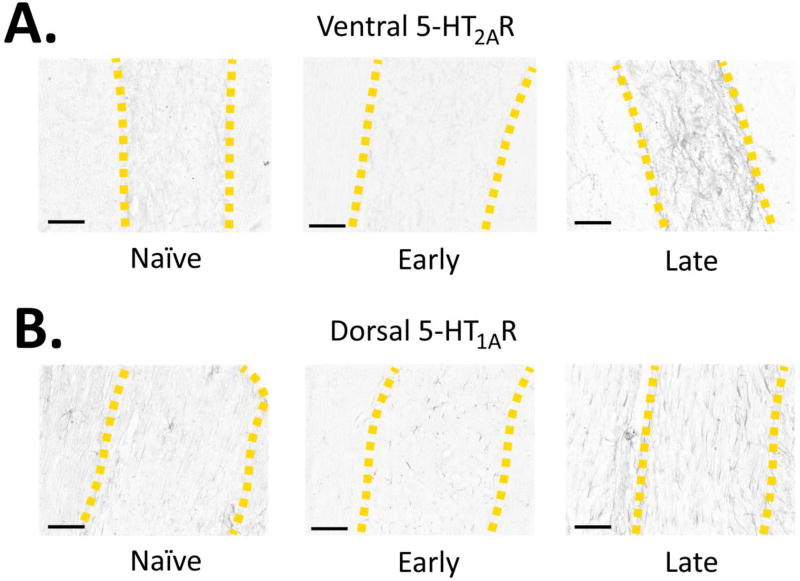

Figure 3. Effect of Time: Exemplar Photomicrographs of Spinal 5-HTR Densities.

Exemplar photomicrographs of the 5-HT2AR (A) and 5-HT1AR (B) immunostains across the Naïve, Early and Late groups (yellow dashed lines = gray matter boundaries). Scale bars = 150 microns.

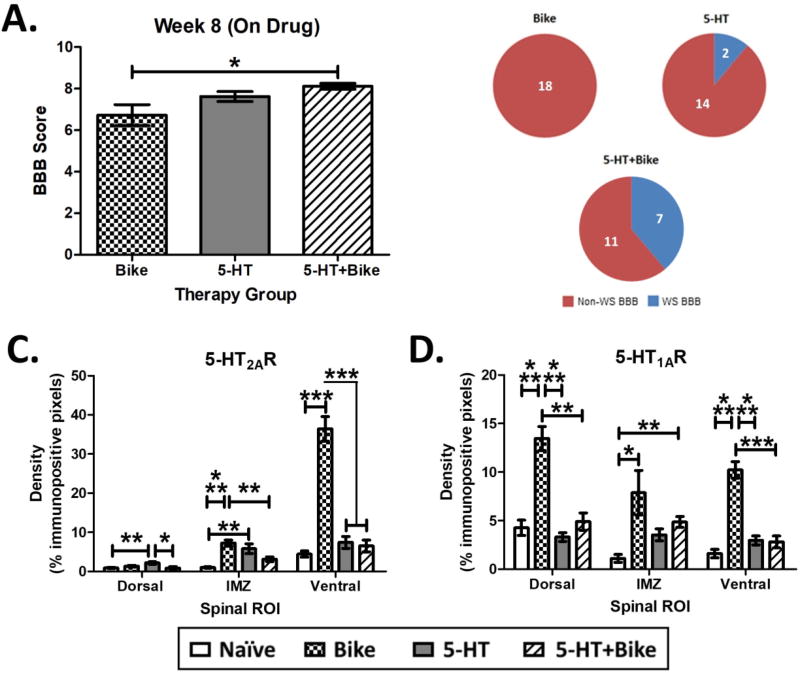

Effect of Therapy on Locomotor Output and Spinal 5-HT Protein Densities

5-HT pharmacotherapy can also be administered chronically in combination with exercise and other therapies to enhance recovery post-SCI (Antri et al., 2002, 2003, 2005; Courtine et al., 2009; van den Brand et al., 2012; Ganzer et al., 2013, Foffani et al., 2016; Ganzer et al., 2016; Manohar et al., 2017). Previous reports have shown significant 5-HTR downregulation following acute or chronic 5-HT pharmacotherapy in supraspinal regions (Gray & Roth, 2001; Riad et al., 2001; Srinivas et al., 2001). However, it is unclear whether chronic 5- HT pharmacotherapy also modulates 5-HTR levels in the spinal cord. 5-HTR density was not correlated with behavioral recovery in Early or Late animals. Assessing the impact of chronic 5-HT pharmacotherapy on both spinal 5-HTR changes and behavioral recovery would provide further insight into the underlying mechanism of 5-HT pharmacotherapy.

To assess the effect of therapy after SCI, we measured BBB score and spinal 5-HT, 5-HT2AR and 5-HT1AR densities caudal to the SCI across the Bike, 5-HT, and 5-HT+Bike groups (Naive = uninjured group for the 5-HT protein assessment; data repeated from effect of time study). 5-HT+Bike animals achieved significantly higher BBB scores compared to Bike animals (Fig. 4A; F(2,25) = 4.3, p = 0.024). 5-HT+Bike also attained a significantly higher proportion of WS BBB scores (7/18) compared to the Bike (0/18) group (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Effect of Therapy on Locomotor Recovery and Spinal 5-HT Protein Densities.

A. At the end of therapy during drug administration, 5-HT+Bike animals achieved significantly higher BBB scores compared to Bike animals (Bike N=9; 5-HT N=8; 5-HT+Bike N=9). Result is from a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. B. 5-HT+Bike animals also achieved a significantly higher proportion of WS (weight-supported) BBB scores when compared to Bike animals (number inset = limbs). Result is from Bonferroni corrected two-proportions tests. C. Chronic 5-HT pharmacotherapy (i.e. 5-HT or 5-HT+Bike therapy) largely prevented the upregulation of spinal 5-HT2AR densities caudal to the SCI seen in Bike animals (N=4 for all groups). D. Chronic 5-HT pharmacotherapy (i.e. 5-HT or 5-HT+Bike therapy) also largely prevented the upregulation of spinal 5-HT1AR densities caudal to the SCI seen in Bike animals (N=4 for all groups). Results in C and D are from separate one-way ANOVAs. * different at p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Data displayed is mean ± S.E.M.

Not surprisingly, there were no detectable 5-HT fibers across groups (week 9 post-SCI; data not shown), as is expected weeks following severe SCI. Bike animals displayed a significant upregulation of both IMZ and Ventral 5-HT2AR compared to Naïve (Fig. 4C; Dorsal: F(3,66) = 4.8, p = 0.004; IMZ: F(3, 61) = 10.1, p < 0.001; Ventral: F(3,65) = 54.9, p < 0.001). Interestingly, 5-HT and 5-HT+Bike therapy both downregulated Ventral 5-HT2AR density compared to Bike (Fig. 4C; Ventral exemplar pictures in Fig. 5A). However, 5-HT animals displayed a significant upregulation of Dorsal and IMZ 5-HT2AR compared to Naïve animals, demonstrating an incomplete receptor density normalization.

Figure 5. Effect of Therapy: Exemplar Photomicrographs of Spinal 5-HTR Densities.

Exemplar photomicrographs of the 5-HT2AR (A) and 5-HT1AR (B) immunostains across the Naïve, Bike, 5-HT and 5-HT+Bike groups (yellow dashed lines = gray matter boundaries). Scale bar = 150 microns.

Bike animals displayed a significant upregulation of Dorsal and Ventral 5-HT1AR density compared to Naïve, 5-HT and 5-HT+Bike animals (Fig. 4D; Dorsal: F(3,64) = 27.2, p < 0.001; IMZ: F(3, 48) = 3.5, p = 0.022; Ventral: F(3,70) = 39.9, p < 0.001). 5-HT and 5-HT+Bike therapy downregulated Dorsal and Ventral 5-HT1AR densities compared to Bike (Fig. 4D; Dorsal exemplar pictures in Fig. 5B). 5-HT+Bike animals also displayed a significant upregulation of IMZ 5-HT1AR compared to Naïve. Therefore, chronically administered 5-HT pharmacotherapy (i.e. 5-HT or 5-HT+Bike therapy) significantly reduces upregulation of the 5-HTR2A and 5-HT1ARs seen in Bike animals. This receptor density reduction is widespread in the spinal gray matter, but not complete in all regions. Importantly, these results also confirm that upregulated spinal 5-HTR levels are not necessary for increased locomotor output post-SCI during 5-HTR agonist treatment. Despite near normal 5-HTR levels, 5-HT+Bike animals achieved significant increases in locomotor ability. There was again no correlation between 5-HT2AR or 5-HT1AR expression and BBB score across groups (data not shown), further supporting our initial conclusion that spinal 5-HTR density does not predict behavioral response to 5-HT agonists following SCI.

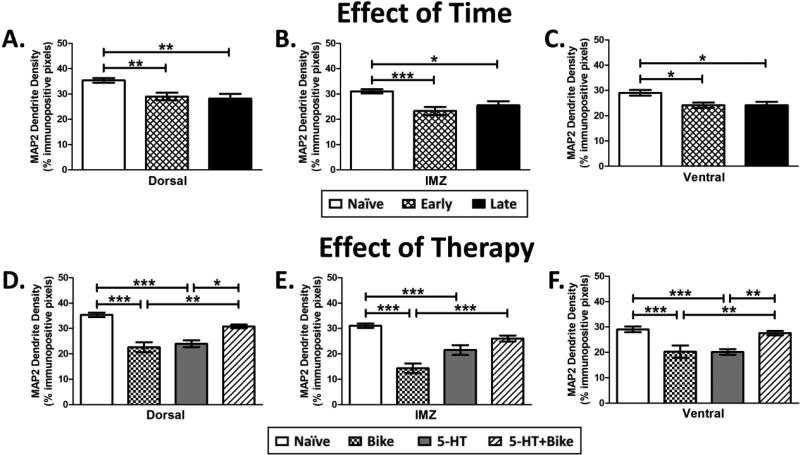

Effect of Time and Therapy on Spinal Dendritic Density (MAP2)

5-HT activates molecular pathways associated with synaptic and dendritic plasticity (Fricker et al., 2005; Azmitia et al., 1995; Jitsuki et al., 2011; Lesch & Waider, 2012). Furthermore, 5-HT pharmacotherapy and neurotrophins upregulated in response to exercise may synergistically interact when administered in combination to further enhance plasticity (Mattson et al., 2004; Foffani et al., 2016). We expected that over time, SCI alone would produce atrophy of dendritic arborization (Zhang et al., 2000). Furthermore, we hypothesized that the combination 5-HT+Bike therapy would enhance anatomical plasticity caudal to the lesion, restoring dendritic density, which could be partially responsible for the increased open-field locomotor performance. We evaluated the effect of time and therapy on dendritic density (MAP2) caudal to the SCI in the Dorsal, IMZ, and Ventral regions across groups.

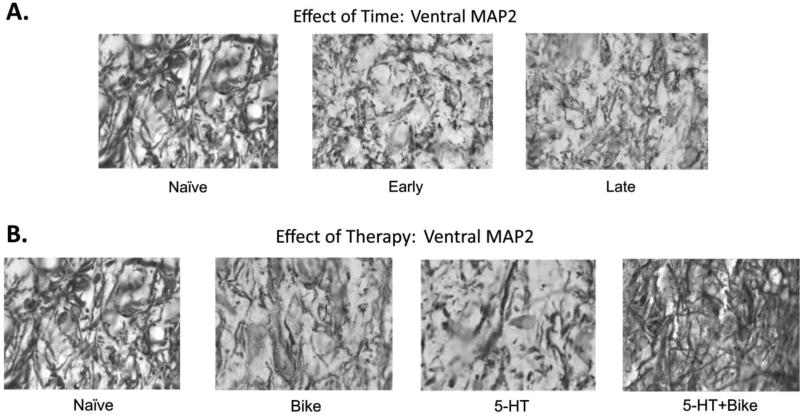

There was an effect of SCI on dendritic density in the Early and Late groups (Fig. 6A–C; Dorsal: F(2,70) = 7.3, p = 0.001; IMZ: F(2,70) = 7.9, p < 0.001; Ventral: F(2,70) = 5.7, p = 0.005). As expected, both Early and Late animals displayed significant decreases in Dorsal, IMZ, and Ventral MAP2 dendrite density compared to uninjured Naïve animals (Fig. 6A–6C; exemplar Ventral MAP2 pictures in 7A). This result suggests that the loss of dendritic processes happens quickly after SCI, in agreement with previous studies (Zhang et al., 2000; Gazula et al., 2004). Therefore, spinal dendritic density decreases precipitously across the gray matter following severe SCI, and the loss is generally maintained weeks later.

Figure 6. Effect of Time and Therapy on MAP2 Dendrite Density.

Early and Late animals displayed significant loss of MAP2 dendrite density within the Dorsal (A), IMZ (B) and Ventral (C) spinal gray caudal to the SCI compared to Naïve animals (N=4 for all groups). 5-HT+Bike therapy restored MAP2 dendrite density within the Dorsal (D), IMZ (E), and Ventral (F) spinal gray caudal to the SCI, promoting a significant increase compared to the 5-HT or Bike groups (N=4 for all groups). Results are from separate one-way ANOVAs. * different at p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Data displayed is mean ± S.E.M.

Figure 7. Effect of Time and Therapy: Exemplar Photomicrographs of MAP2 Dendrites.

Exemplar photomicrographs of Ventral MAP2 dendrites for the effect of time (A) or effect of therapy (B) studies. Corresponding dendritic density values for the photomicrographs: Naïve = 36.6%, Early = 21.6%, Late = 20%, Bike = 20%, 5-HT = 20.6%, 5-HT+Bike = 24.8%.

There was also an effect of therapy on dendritic density (Fig. 6D–6F; Dorsal: F(3,69) = 21.1, p < 0.001; IMZ: F(3,73) = 23.8, p < 0.001; Ventral: F(2,82) = 11, p < 0.001). Bike alone and 5-HT alone displayed significant decreases in Dorsal, IMZ, and Ventral MAP2 dendrite density compared to uninjured Naïve animals (Fig. 6D–6F; exemplar Ventral MAP2 pictures in 7B). However, the combination of 5-HT+Bike therapy restored dendritic density lost within the first week post SCI, resulting in significant increased density compared to both Bike (Dorsal, IMZ, and Ventral) and 5-HT animals (Dorsal and Ventral) (Fig. 6D–6F). Therefore, complete midthoracic SCI significantly decreases dendritic density in: 1) animals at both acute (Early) and chronic (Late) stages of SCI as well as 2) animals receiving a single therapeutic intervention (Bike or 5-HT). The combination 5-HT+Bike therapy restored dendritic density, which was accompanied by a lack of 5-HTR upregulation and increases in open-field WS locomotor recovery.

Discussion

Here we examined the effect of time and therapy on post-SCI locomotor recovery, spinal 5-HTR plasticity (5-HT2AR, 5-HT1AR), and dendritic plasticity (MAP2). As previously reported, dendritic atrophy occurred early after SCI, and was maintained weeks later without therapy. Furthermore, complete 5-HT fiber degeneration was accompanied by upregulated spinal 5-HTRs. Acute administration of combinations of 5-HTR agonists were studied to identify doses that enhanced locomotor output without significant side effects. Importantly, an acute dose of 5-HTRs acted on upregulated 5-HTRs to improve locomotor behavior late (week 9 post-injury) after SCI compared to early (week 1 post-injury). Yet, the locomotor improvement was not sufficient to allow animals to achieve weight-supported stepping, likely due to the significant atrophy of spinal dendritic processes caudal to the SCI. A combination therapy of 5-HT+Bike promoted significant increases in open-field weight-supported stepping while normalizing 5-HTR levels and reversing dendritic atrophy. Behavioral recovery was not correlated to 5-HTR density regardless of therapy. These results provide important insights into how combination therapies can act on different anatomical substrates and work together to improve behavioral outcome better than either therapy alone (Foffani et al., 2016).

The 5-HTR density results presented here do not necessarily represent an exact quantitation of spinal protein levels. Alternative molecular methods (western blot or HPLC) would allow for exact spinal protein level measurement. However, knowledge of the spatial distribution of 5-HTR changes within the spinal gray matter is essential for understanding and interpreting the effect of receptor plasticity on locomotor performance. Previous studies have assessed cell specific changes in serotonergic function following SCI (Murray et al., 2010; Husch et al., 2012). However, this was not the focus of the current study. Nonetheless, our measurements of spinal 5-HTR densities following SCI are consistent with previous studies and help to demonstrate a deeper understanding of the potential mechanisms underlying behavioral recovery after SCI. For example, after complete spinal transection at S2, Kong et al. (2011) utilized 5-HT2AR IHC followed by density measurements to show similar upregulation of this protein caudal to the injury. These investigators reported up to a 5-fold increase 5-HT2AR protein density in ventral gray caudal to the SCI 4 weeks after injury. More recently, Navarrett et al. (2012) reported an upregulation of 5-HT2AR mRNA caudal to a midthoracic spinal transection 6 weeks post-SCI. Also, Otoshi et al. (2010) reported an almost 2-fold increase in 5-HT1AR positive processes in the spinal gray matter caudal to a midthoracic spinal transection 8 weeks post-SCI. Future studies may aim to utilize additional molecular techniques in parallel with IHC approaches to further quantify spinal protein levels.

SCI groups displaying both upregulated 5-HTRs and atrophied dendritic processes (i.e. the Late and Bike groups) were never able to achieve weight supported open-field locomotion. 5-HTR upregulation is undoubtedly due to the degeneration of 5-HT axons following SCI induced axotomy (Hadjiconstantinou et al., 1984; Kong et al., 2011). Our findings corroborate with previous studies demonstrating that full 5-HT fiber degeneration is not complete at one week post-SCI (i.e. in Early animals; Hadjiconstantinou et al., 1984; Kong et al., 2011). SCI also damages descending motor pathways, depriving the caudal spinal circuitry of supraspinal input promoting paralysis, dendritic retraction, and dendritic atrophy (Byers et al., 2012; Little et al. 2009, Zhang et al., 2000; Gazula et al., 2004). Dendritic arbor density is intimately related to synaptic input density (Hume & Purves, 1981; Purves & Hume, 1981). Reductions in activity can also facilitate synaptic elimination (Constantine-Paton et al., 1990; Constantine-Paton & Cline, 1998). Modifications to dendritic and synaptic plasticity affects electrophysiological processing of incoming signals (Nusser, 1999; Vetter et al., 2001) and subsequent network function post injury (Petruska et al., 2007). Therefore, dendritic spinal atrophy significantly limited open-field locomotor recovery across groups, regardless of upregulated 5-HTRs for the 5-HTR agonist combination to act upon.

It is important to note that locomotion, especially after SCI, involves sensorimotor networks above and below the lesion (Giszter et al., 2010; Shah et al., 2013). Several studies have shown that cortical reorganization supports recovery following SCI (Manohar et al., 2017; Serradj et al., 2016; Moxon et al., 2014; Foffani et al., 2016; Xerri et al., 2012; van den Brand et al., 2012; Kao et al., 2009; Giszter et al., 2008). For example, Moxon et al. 2013 showed that the state of somatosensory cortical networks following neonatal SCI plays a major role in locomotor output induced by the 5-HT2R agonist mCPP. Moreover, previous studies have demonstrated that 5-HT and Bike therapy significantly enhance plasticity in somatosensory (Graziano et al., 2013; Ganzer et al., 2013) and motor cortices (Ganzer et al., 2016). Therefore, these results support a model in which combination therapies enhance plasticity at multiple levels of the sensorimotor neuraxis to improve recovery after severe SCI.

Previous reports have shown significant 5-HTR downregulation following acute or chronic 5-HT pharmacotherapy in supraspinal regions (Gray & Roth, 2001; Riad et al., 2001; Srinivas et al., 2001) when the endogenous 5-HT system was intact. However, it was unclear whether daily 5-HT pharmacotherapy would modulate spinal 5-HTR plasticity following SCI that eliminates 5-HT caudal to the lesion. Reversing spinal neuromodulator receptor (norepinephrine, α1) upregulation has been shown previously following SCI using intraspinal implants of locus coeruleus cells, suggesting that spinal receptor densities are plastic and can be upregulated and downregulated following SCI and treatment (Roudet et al., 1995 & 1996). Here, a single daily injection of 5-HTR agonists for several weeks was sufficient to largely prevent the upregulation of 5-HTRs caudal to the SCI throughout the spinal gray matter.

Despite near normal 5-HTR levels, 5-HT+Bike animals still achieved open field weight-supported locomotion. Because 5-HT affects cellular neurophysiology via complex G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) cascades (Hochman et al., 2001), there are several avenues by which relatively low 5-HTR levels can still promote significant locomotor output post-SCI. Restoring dendritic density as discussed above can mediate synaptic connectivity enhancement related to improved function. Moreover, chronic administration of GPCR agonists have shown increased agonist-receptor affinity and prolonged agonist binding (Birdsong et al. 2013), allowing activation of receptors to be prolonged and more effective. Furthermore, increases in receptor coupling to intracellular cascades can amplify the effects of delivered agonists (Kenakin, 1995a, 1995b). Receptor binding and signaling pathway plasticity should be assessed in future studies to further determine the cellular and intracellular effects of post-injury chronic pharmacotherapy.

Post-SCI MAP2 dendritic plasticity can be achieved through a variety of interventions and molecular pathway activations including hormone treatment (González et al., 2009), hypothermia (Yu et al., 2000) and glutamate release inhibitor treatment (Springer et al. 1997). Here we extend these findings demonstrating an enhancement of spinal MAP2 plasticity related to recovery following a combination of 5-HT and exercise therapy. Interestingly, 5-HT treatment alone facilitates MAP2 dendritic plasticity after lesions incompletely eliminating 5-HT in the brain (Azmitia et al., 1995). This is in contrast to the lack of effect of 5-HT treatment alone on spinal MAP2 shown in this study following complete spinal 5-HT elimination. With regards to exercise, five days of a similar passive hindlimb bicycling following SCI in young (P23) rats was sufficient to increase hindlimb motor neuron dendritic density (Gazula et al., 2004). However, here following SCI as an adult even longer duration (7 weeks) passive hindlimb bicycling alone was ineffective at restoring dendritic density and enabling weight supported open-field locomotion. This result highlights the differential effect of exercise therapy following neonatal vs. adult SCI. Together, these results from single therapies demonstrate that upregulated 5-HTRs alone are not sufficient to enable weight supported locomotor output following 5-HT pharmacology. Only a combination therapy of 5-HT+Bike normalized 5-HTR and dendritic density to enable weight-supported locomotor ability.

The role of 5-HT (Lesch & Waider, 2012) and exercise (Vaynman et al., 2005) in promoting plasticity is well established. The activation of 5-HTRs induces synaptic and structural plasticity either directly or through neuron-glia interactions (Fricker et al., 2005; Jitsuki et al, 2011; Azmitia et al., 1995; Nishi et al., 1996 & 1997; Ramos et al., 2004). Passive bicycling exercise after SCI can increase plasticity by upregulating neurotrophic factors (Côté et al., 2011; Keeler et al. 2012) through modulation of microRNAs (Liu et al. 2012). Furthermore, the combination 5-HT+Bike therapy had a greater impact on spinal plasticity compared to either 5-HT or Bike alone, suggesting that these therapies may act synergistically when administered in combination (Mattson et al., 2004). Therefore, both 5-HT and exercise affect neuronal plasticity. However, these results suggest that combination therapies may be needed to promote significant locomotor recovery following severe SCI as an adult.

Additional work is required to fully understand the mechanisms underlying the combined 5-HT and exercise therapy’s support of locomotor recovery after SCI. However, the results reported here demonstrate that continued upregulation of spinal 5-HTRs is not necessary for pharmacologically mediated recovery. Interestingly, spinal dendritic atrophy significantly limited locomotor recovery, regardless of upregulated spinal 5-HTRs for 5-HT pharmacotherapy to act upon. We hypothesize that synergistic combination therapies can maximally enhance spinal plasticity to enable recovery compared to single therapies alone. Furthermore, these findings provide important knowledge for designing pharmacological therapies, and alleviates the burden of requiring dose regimens that preserve the initial upregulation of 5-HTRs after SCI.

Table 1.

Summary for Effect of Time on 5-HTR density changes (accompanying data in Figure panels 2C & 2D; mean ± S.E.M.)

| 5-HT2AR | 5-HT1AR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorsal | IMZ | Ventral | Dorsal | IMZ | Ventral | |

| Naïve | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 1.02 ± 0.17 | 4.44 ± 0.80 | 4.26 ± 0.79 | 1.11 ± 0.41 | 1.61 ± 0.44 |

| Early | 0.75 ± 0.28 | 2.10 ± 0.79 | 2.98 ± 0.49 | 5.50 ± 0.66 | 5.65 ± 0.79 | 2.79 ± 0.42 |

| Late | 1.17 ± 0.27 | 3.60 ± 0.83 | 27.78 ± 3.28 | 10.60 ± 1.55 | 7.06 ± 1.85 | 4.04 ± 0.70 |

Table 2.

Summary for Effect of Therapy on 5-HTR density changes (accompanying data in Figure panels 4C & 4D; mean ± S.E.M.)

| 5-HT2AR | 5-HT1AR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorsal | IMZ | Ventral | Dorsal | IMZ | Ventral | |

| Naïve | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 1.02 ± 0.17 | 4.44 ± 0.80 | 4.26 ± 0.79 | 1.11 ± 0.41 | 1.61 ± 0.44 |

| Bike | 1.34 ± 0.24 | 7.25 ± 0.76 | 36.45 ± 3.13 | 13.46 ± 1.24 | 7.88 ± 2.29 | 10.22 ± 0.86 |

| 5-HT | 2.17 ± 0.32 | 5.82 ± 1.26 | 7.42 ± 1.51 | 3.31 ± 0.45 | 3.54 ± 0.62 | 2.97 ± 0.46 |

| 5-HT+Bike | 0.85 ± 0.36 | 3.13 ± 0.60 | 6.51 ± 1.51 | 4.90 ± 0.89 | 4.86 ± 0.56 | 2.81 ± 0.61 |

Highlights.

5-HT pharmacotherapy combined with bike exercise therapy (5-HT+Bike) promoted significant 5-HT receptor and dendritic plasticity in the spinal cord. This combination therapy furthermore promoted significant gains in weight supported open field locomotion compared to single therapies.

5-HT+Bike was able to enhance locomotor recovery despite acting on largely normal levels of spinal 5-HT receptors.

Groups displaying significantly atrophied dendritic processes were rarely able to achieve weight supported open-field locomotion.

These results support the use of combined therapies to synergistically impact spinal plasticity and improve motor recovery.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adkins-Muir DL, Jones TA. Cortical electrical stimulation combined with rehabilitative training: enhanced functional recovery and dendritic plasticity following focal cortical ischemia in rats. Neurol Res. 2003;25(8):780–8. doi: 10.1179/016164103771953853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antri M, Orsal D, Barthe JY. Locomotor recovery in the chronic spinal rat: effects of long-term treatment with a 5-HT2 agonist. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:467–476. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antri M, Mouffle C, Orsal D, Barthe JY. 5-HT1A receptors are involved in short- and long-term processes responsible for 5-HT-induced locomotor function recovery in chronic spinal rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;18:1963–1972. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antri Antri M, Barthe JY, Mouffle C, Orsal D. Long-lasting recovery of locomotor function in chronic spinal rat following chronic combined pharmacological stimulation of serotonergic receptors with 8-OHDPAT and quipazine. Neurosci Lett. 2005;384(1–2):162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azmitia EC, Rubinstein VJ, Strafaci JA, Riaos JC, Whitaker-Azmitia PM. 5-HT1A agonist and dexamethasone reversal of parachloroamphetamine induced loss of MAP-2 and synaptophysin immunoreactivity in adult rat brain. Brain Res. 1995;677:181–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00051-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12:1–21. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birdsong William T, Seksiri Arttamangkul, Clark Mary J, Kejun Cheng, Rice Kenner C, Traynor John R, Williams John T. Increased Agonist Affinity at the µ-Opioid Receptor Induced by Prolonged Agonist Exposure. The Journal of Neuroscience: the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013 Feb 27;33(9):4118–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4187-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowker RM, Westlund KN, Coulter JD. Origins of serotonergic projections to the spinal cord in rat: an immunocytochemical-retrograde transport study. Brain Res. 1981;226(1–2):187–99. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)91092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byers JS, Huguenard AL, Kuruppu D, Liu NK, Xu XM, Sengelaub DR. Neuroprotective effects of testosterone on motoneuron and muscle morphology following spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:2683–2696. doi: 10.1002/cne.23066. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Constantine-Paton M, Cline HT. LTP and activity-dependent synaptogenesis: the more alike they are, the more different they become. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Constantine-Paton M, Cline HT, Debski E. Patterned activity, synaptic convergence, and the NMDA receptor in developing visual pathways. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:129–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Côté Marie-Pascale, Gregorya Azzam, Michela Lemay, Victoria Zhukareva, Houlé John D. Activity-dependent increase in neurotrophic factors is associated with an enhanced modulation of spinal reflexes after spinal cord injury. Journal of neurotrauma. 2011;28(2):299–309. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Courtine G, Gerasimenko Y, van den Brand R, Yew A, Musienko P, Zhong H, et al. Transformation of nonfunctional spinal circuits into functional states after the loss of brain input. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1333–42. doi: 10.1038/nn.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Mello MT, Esteves AM, Tufik S. Comparison between dopaminergic agents and physical exercise as treatment for periodic limb movements in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:218–221. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Detloff MR, Smith EJ, Quiros Molina D, Ganzer PD, Houlé JD. Acute exercise prevents the development of neuropathic pain and the sprouting of non-peptidergic (GDNF- and artemin-responsive) c-fibers after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2014;255:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dugan E., PhD . Combination therapy enhances recovery of function from complete spinal cord injury. Dept of Neurobiology and Anatomy, Drexel University College of Medicine; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dugan EA, Shumsky JS. A combination therapy of neural and glial restricted precursor cells and chronic quipazine treatment paired with passive cycling promotes quipazine-induced stepping in adult spinalized rats. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38(6):792–804. doi: 10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foffani G, Shumsky J, Knudsen EB, Ganzer PD, Moxon KA. Interactive Effects Between Exercise and Serotonergic Pharmacotherapy on Cortical Reorganization after Spinal Cord Injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016;30(5):479–89. doi: 10.1177/1545968315600523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fricker AD, Rios C, Devi LA, Gomes I. Serotonin receptor activation leads to neurite outgrowth and neuronal survival. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005;138:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juanjuan Fu, Hongxing Wang, Lingxiao Deng, Jianan Li. Exercise Training Promotes Functional Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. Neural Plast. 2016:4039580. doi: 10.1155/2016/4039580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganzer PD, Moxon KA, Knudsen EB, Shumsky JS. Serotonergic pharmacotherapy promotes cortical reorganization after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;241:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganzer PD, Manohar A, Shumsky JS, Moxon KA. Therapy induces widespread reorganization of motor cortex after complete spinal transection that supports motor recovery. Exp Neurol. 2016;279:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gazula VR, Roberts M, Luzzio C, Jawad AF, Kalb RG. Effects of limb exercise after spinal cord injury on motor neuron dendrite structure. J Comp Neurol. 2004;476(2):130–45. doi: 10.1002/cne.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giszter S, Davies MR, Ramakrishnan A, Udoekwere UI, Kargo WJ. Trunk sensorimotor cortex is essential for autonomous weight-supported locomotion in adult rats spinalized as P1/P2 neonates. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:839–851. doi: 10.1152/jn.00866.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giszter Simon F, Greg Hockensmith, Arun Ramakrishnan, Ubong Ime Udoekwere. How Spinalized Rats Can Walk: Biomechanics, Cortex, and Hindlimb Muscle Scaling--Implications for Rehabilitation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010 Jun;1198:279–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.González Susana L, Juan José López-Costa, Florencia Labombarda, Maria Claudia González Deniselle, Rachida Guennoun, Michael Schumacher, De Nicola Alejandro F. Progesterone Effects on Neuronal Ultrastructure and Expression of Microtubule-Associated Protein 2 (MAP2) in Rats with Acute Spinal Cord Injury. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2009 Mar;29(1):27–39. doi: 10.1007/s10571-008-9291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray JA, Roth BL. Paradoxical trafficking and regulation of 5-HT(2A) receptors by agonists & antagonists. Brain Res. Bull. 2001;56(5):441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graziano A, Foffani G, Knudsen EB, Shumsky J, Moxon KA. Passive exercise of the hind limbs after complete thoracic transection of the spinal cord promotes cortical reorganization. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadjiconstantinou M, Panula P, Lackovic Z, Neff NH. Spinal cord serotonin: a biochemical and immunohistochemical study following transection. Brain Res. 1984;322:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harada A, Teng J, Takei Y, Oguchi K, Hirokawa N. MAP2 is required for dendrite elongation, PKA anchoring in dendrites, and proper PKA signal transduction. J Cell Biol. 2002;158(3):541–549. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hochman S, Garraway SM, Machacek DW, Shay BL. 5-HT receptors and the neuromodulatory control of spinal cord function. In: Cope TC, editor. Motor Neurobiology of the Spinal Cord. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2001. pp. 47–87. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houle JD, Morris K, Skinner RD, Garcia-Rill E, Peterson CA. Effects of fetal spinal cord tissue trans- plants and cycling exercise on the soleus muscle in spinalized rats. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:846–856. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199907)22:7<846::aid-mus6>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hume RI, Purves D. Geometry of neonatal neurons and the regulation of synapse elimination. Nature. 1981;293(5832):469–71. doi: 10.1038/293469a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Husch A, Van Patten GN, Hong DN, Scaperotti MM, Cramer N, Harris-Warrick RM. Spinal cord injury induces serotonin supersensitivity without increasing intrinsic e xcitability of mouse V2a interneurons. J Neurosci. 2012;32(38):13145–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2995-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jitsuki S, Takemoto K, Kawasaki T, Tada H, Takahashi A, Becamel C, et al. Serotonin mediates cross-modal reorganization of cortical circuits. Neuron. 2011;69:780–792. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kao T, Shumsky JS, Jacob-Vadakot S, Himes BT, Murray M, Moxon KA. Role of the 5-HT2C receptor in improving weight-supported stepping in adult rats spinalized as neonates. Brain Res. 2006;1112:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keeler BE, Liu G, Siegfried RN, Zhukareva V, Murray M, et al. Acute and prolonged hindlimb exercise elicits different gene expression in motoneurons than sensory neurons after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 2012;1438:8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kenakin T. Agonist-receptor efficacy I: Mechanisms of efficacy and receptor promiscuity. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995a;16(6):188–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kenakin T. Agonist-receptor efficacy. II. Agonist trafficking of receptor signals. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995b;16(7):232–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kjaerulff O, Kiehn O. Distribution of Networks Generating and Coordinating Locomotor Activity in the Neonatal Rat Spinal Cord in Vitro: a Lesion Study. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996 Sep 15;16(18):5777–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05777.1996. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8795632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kong XY, Wienecke J, Hultborn H, Zhang M. Robust upregulation of serotonin 2A receptors after chronic spinal transection of rats: an immunohistochemical study. Brain Res. 2010;1320:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kong XY, Wienecke J, Chen M, Hultborn H, Zhang M. The time course of serotonin 2A receptor expression after spinal transection of rats: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroscience. 2011;177:114–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kremer E, Lev-Tov a. “Localization of the Spinal Network Associated with Generation of Hindlimb Locomotion in the Neonatal Rat and Organization of Its Transverse Coupling System”. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997 Mar;77(3):1155–70. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1155. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9084588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Landry ES, Guertin PA. Differential effects of 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptor agonists on hindlimb movements in paraplegic mice. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;28(6):1053–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Landry ES, Lapointe NP, Rouillard C, Levesque D, Hedlund PB, Guertin PA. Contribution of spinal 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 receptors to locomotor-like movement induced by 8-OH-DPAT in spinal cord-transected mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;24(2):535–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lauer RT, Smith BT, Mulcahey MJ, Betz RR, Johnston TE. Effects of cycling and/or electrical stimulation on bone mineral density in children with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:917–923. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JK, Johnson CS, Wrathall JR. Up-regulation of 5-HT2 receptors is involved in the increased H-reflex amplitude after contusive spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2007;203(2):502–11. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lesch KP, Waider J. Serotonin in the modulation of neural plasticity and networks: implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuron. 2012;76(1):175–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Little CM, Coons KD, Sengelaub DR. Neuroprotective effects of testosterone on the morphology and function of somatic motoneurons following the death of neighboring motoneurons. J Comp Neurol. 2009;512:359–372. doi: 10.1002/cne.21885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Gang, Megan Ryan Detloff, Miller Kassi N, Lauren Santi, Houlé John D. Exercise Modulates microRNAs That Affect the PTEN/mTOR Pathway in Rats after Spinal Cord Injury. Experimental Neurology. 2012 Jan;233(1):447–56. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manohar A, Foffani G, Ganzer PD, Bethea J, Moxon KA. Cortex-dependent recovery of unassisted hindlimb locomotion after complete spinal cord injury in adult rats. eLife. 2017;6:e23532. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin TG. Serotonin syndrome. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1996;20:520–526. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mattson MP, Maudsley S, Martin B. BDNF and 5-HT: a dynamic duo in age-related neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moxon KA, Kao T, Shumsky JS. Role of cortical reorganization on the effect of 5-HT pharmacotherapy for spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;240:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moxon KA, Oliviero A, Aguilar J, Foffani G. Cortical reorganization after spinal cord injury: always for good? Neuroscience. 2014;283:78–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murray KC, Nakae A, Stephens MJ, Rank M, D'Amico J, Harvey PJ, Li X, Harris RL, Ballou EW, Anelli R, Heckman CJ, Mashimo T, Vavrek R, Sanelli L, Gorassini MA, Bennett DJ, Fouad K. Recovery of motorneuron and locomotor function after spinal cord injury depends on constitutive activity in 5-HT2C receptors. Nat Med. 2010;16(6):694–700. doi: 10.1038/nm.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Musienko P, van den Brand R, Märzendorfer O, Roy RR, Gerasimenko Y, Edgerton VR, Courtine G. Controlling specific locomotor behaviors through multidimensional monoaminergic modulation of spinal circuitries. J Neurosci. 2011;31(25):9264–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5796-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Navarrett S, Collier L, Cardozo C, Dracheva S. Alterations of serotonin 2C and 2A receptors in response to T10 spinal cord transections in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2012;506(1):74–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishi PM, Whitaker-Azmitia, E Azmitia C. Enhanced synaptophysin immunoreactivity in rat hippocampal culture by 5- HT1A agonist, S100β and corticosteroid receptor agonists. Synapse. 1996;23:1–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199605)23:1<1::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishi M, Kawata M, Azmitia EC. S100B promotes the extension of microtubule associated protein2 (MAP2)-immunoreactive neurites retracted after colchicines treatment in rat spinal cord culture. Neurosci. Lett. 1997;229:212–214. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nothias JM, Matsui T, Shumsky JS, Fischer I, Antonacci MD, Murray M. Combined effects of neurotrophin secreting transplants, exercise, and serotonergic drug challenge improve function in spinal rats. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2005 Dec;19(4):296–312. doi: 10.1177/1545968305281209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nusser Z. Subcellular distribution of neurotransmitter receptors and voltage-gated ion channel. In: Stuart G, Spruston N, Hausser M, editors. Dendrites. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Otoshi CK, Walwyn WM, Tillakaratne NJ, Zhong H, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Distribution and localization of 5-HT(1A) receptors in the rat lumbar spinal cord after transection and deafferentation. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:575–584. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petruska JC, Ichiyama RM, Jindrich DL, Crown ED, Tansey KE, Roy RR, Edgerton VR, Mendell LM. Changes in motoneuron properties and synaptic inputs related to step training after spinal cord transection in rats. J Neurosci. 2007;27(16):4460–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2302-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phadke CP, Flynn SM, Thompson FJ, Behrman AL, Trimble MH, et al. Comparison of single bout effects of bicycle training versus locomotor training on paired reflex depression of the soleus H-reflex after motor incomplete spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1218–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Phillips WT, Kiratli BJ, Sarkarati M, Weraarchakul G, Myers J, et al. Effect of spinal cord injury on the heart and cardiovascular fitness. Curr Probl Cardiol. 1998;23:641–716. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2806(98)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Purves D, Hume RI. The relation of postsynaptic geometry to the number of presynaptic axons that innervate autonomic ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 1981;1:441–452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-05-00441.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Riad M, Watkins KC, Doucet E, Hamon M, Descarries L. Agonist-induced internalization of serotonin-1a receptors in the dorsal raphe nucleus (autoreceptors) but not hippocampus (heteroreceptors) J Neurosci. 2001;21:8378–8386. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08378.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ramos AJ, Rubio MD, Defagot C, Hischberg L, Villar MJ, Brusco A. The 5-HT1A receptor agonist, 8-OH-DPAT, protects neurons and reduces astroglial reaction after ischemic damage caused by cortical devascularization. Brain Res. 2004;1030:201–220. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roudet C, Giménezy Ribotta M, Privat A, Feuerstein C, Savasta M. Intraspinal noradrenergic-rich implants reverse the increase of alpha 1 adrenoceptors densities caused by complete spinal cord transection or selective chemical denervation: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Brain Res. 1995;677(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roudet C, Gimenez Ribotta M, Privat A, Feuerstein C, Savasta M. Regional study of spinal alpha 2-adrenoceptor densities after intraspinal noradrenergic-rich implants on adult rats bearing complete spinal cord transection or selective chemical noradrenergic denervation. Neurosci Lett. 1996;208(2):89–92. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Serradj N, Agger SF, Hollis ER., 2nd Corticospinal circuit plasticity in motor rehabilitation from spinal cord injury. Neurosci Lett. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.12.003. S0304-3940(16)30938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shah Prithvi K, Guillermo Garcia-Alias, Jaehoon Choe, Parag Gad, Yury Gerasimenko, Niranjala Tillakaratne, Hui Zhong, Roy Roland R, Edgerton V Reggie. Use of Quadrupedal Step Training to Re-Engage Spinal Interneuronal Networks and Improve Locomotor Function after Spinal Cord Injury. Brain : a Journal of Neurology. 2013 Oct 7; doi: 10.1093/brain/awt265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Skagerberg G, Bjorklund A. Topographic principles in the spinal projections of serotonergic and non-serotonergic brainstem neurons in the rat. Neuroscience. 1985;15:445–480. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Springer JE, Azbill RD, Kennedy SE, George J, Geddes JW. Rapid Calpain I Activation and Cytoskeletal Protein Degradation Following Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: Attenuation with Riluzole Pretreatment. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;69(4):1592–600. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Srinivas BN, Subhash MN, Vinod KY. Cortical 5-HT(1A) receptor downregulation by antidepressants in rat brain. Neurochem Int. 2001;38(7):573–9. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(00)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ung RV, Landry ES, Rouleau P, Lapointe NP, Rouillard C, Guertin PA. Role of spinal 5-HT2 receptor subtypes in quipazine-induced hindlimb movements after a low-thoracic spinal cord transection. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;11:2231–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van den Brand R, Heutschi J, Barraud Q, DiGiovanna J, Bartholdi K, et al. Restoring voluntary control of locomotion after paralyzing spinal cord injury. Science. 2012;336:1182–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.1217416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vaynman Shoshanna, Fernando Gomez-Pinilla. “License to run: exercise impacts functional plasticity in the intact and injured central nervous system by using neurotrophins”. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2005;19(4):283–95. doi: 10.1177/1545968305280753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vetter P, Roth A, Hausser M. Propagation of action potentials in dendrites depends on dendritic morphology. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:926–937. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xerri C. Plasticity of cortical maps: multiple triggers for adaptive reorganization following brain damage and spinal cord injury. Neuroscientist. 2012;18(2):133–48. doi: 10.1177/1073858410397894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yu WR, Westergren H, Farooque M, Holtz A, Olsson Y. Systemic hypothermia following spinal cord compression injury in the rat: an immunohistochemical study on MAP2 with special reference to dendrite changes. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100(5):546–52. doi: 10.1007/s004010000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang SX, Underwood M, Landfield A, Huang FF, Gison S, Geddes JW. Cytoskeletal disruption following contusion injury to the rat spinal cord. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59(4):287–96. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]