Abstract

Variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs) are unconventional adaptive immune receptors relatively recently discovered in the phylogenetically ancient jawless vertebrates, lamprey and hagfish. VLRs bind antigens using a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) fold and are the only known adaptive immune receptors that do not utilize an immunoglobulin (Ig) fold for antigen recognition. While Ig-antibodies have been studied extensively, there are comparatively few studies on antigen recognition by VLRs, particularly for protein antigens. Here we report isolation, functional and structural characterization of three VLRs that bind the protein toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) from zebrafish. Two of the VLRs block binding of TLR5 to its cognate ligand flagellin in functional assays using reporter cells. Co-crystal structures revealed that these VLRs bind to two different epitopes on TLR5, both of which include regions involved in flagellin binding. Our work here demonstrates that the lamprey adaptive immune system can be used to generate high affinity VLR clones that recognize different epitopes and differentially impact natural ligand binding to a protein antigen.

Keywords: innate immunity, antigen binding, leucine-rich repeat, protein-protein complex, X-ray crystallography

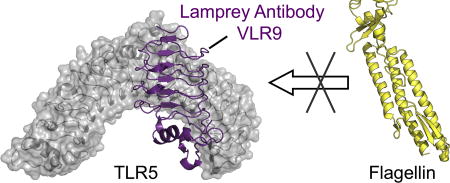

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Antibodies are widely used in biomedical research and medical applications due to their exquisite molecular recognition properties. Variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs) are phylogenetically ancient antibodies discovered in the extant jawless vertebrates, lamprey and hagfish1, 2. VLRs from lamprey and hagfish are the only known vertebrate antibodies that do not have an immunoglobulin (Ig) fold (REF). Instead, leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) form the basis of VLR antigen recognition2–4. Jawless and jawed vertebrates (Agnatha and Gnathostomata, respectively) evolved different lymphocyte-based adaptive immune systems approximately 500 million years ago5. VLRs are assembled during lymphocyte development by sequential recombination of flanking LRR modules into an incomplete germline VLR gene locus until an in-frame, functional VLR gene is formed2. An estimated repertoire of >1014 unique VLR receptors can be generated by this gene assembly mechanism, which enables lampreys to respond to a vast array of antigens1. Three classes of VLR (VLRA, VLRB, and VLRC) are encoded in lamprey and hagfish6–8. VLRA+ and VLRC+ lymphocytes employ their diverse repertoires of cell surface VLRAs and VLRCs, respectively, for cell-mediated immune responses9. VLRB+ lymphocytes provide humoral immunity, expressing membrane-anchored VLRB and also secreting multivalent VLRB, and thus have drawn parallels to mammalian B cells3, 10. Secreted VLRBs multimerize via a conserved C-terminal stalk region, which is necessary for agglutination1, 3. The VLRB LRR domain is responsible for antigen binding11–14.

Structurally, the VLRB antigen-binding domain is crescent-shaped and comprised of an N-terminal LRR cap (LRRNT), LRR1, one or more variable LRRs (LRRV), LRRV-end (LRRVe), a connecting peptide (CP) and a C-terminal LRR cap (LRRCT) with a variable insert (CT-loop)12. Antigen binding occurs on the hypervariable concave surface formed by β-strands from adjacent LRRs and the hypervariable CT-loop11–14. In the VLRB:antigen crystal structures determined so far, the CT-loop forms an extended structure that projects toward the concave surface and is akin, to some extent, to CDRH3 of conventional antibodies12, 14, 15. This loop has been implicated as a key determinant for binding carbohydrate antigens12, 16. Our understanding of how VLRBs recognize protein antigens has thus far been limited to two examples: hen egg lysozyme and the Bacillus collagen-like protein of anthracis spores (BclA)13, 14. Given the extremely limited structural information for VLRBs in complex with protein antigens, additional context can be gleaned from the structure of a VLRA in complex with hen egg lysozyme, which binds with picomolar affinity, although it is still not clear what constitutes a typical VLRA antigen recognition mode17–19. Crystal structures of these antigen-VLR complexes showed that both protein antigens bound to the CT-loop and the more C-terminal β-strands, but not to the LRRNT.

There is significant interest in developing molecular recognition proteins using scaffolds other than the Ig fold of conventional antibodies, in part to streamline production, facilitate engineering of fusion constructs, or to overcome self-tolerance20. The vast repertoires of VLRs with LRR-based recognition motifs offer relatively untapped potential to complement Ig-based antibody technologies. VLR monomers are small (~15–25 kDa) and their formation by a single polypeptide chain simplifies the construction of recombinant fusion proteins and display libraries for high-throughput screening3. For example, VLR-containing chimeric antigen receptors have been engineered that target murine B cell leukemia and the human T cell surface antigen CD521. Relative to VLRs, Igs are large (~150 kDa for IgG) proteins and production typically requires heavy and light chains22. The only known naturally occurring single chain Ig-antibodies are the camelid heavy chain antibodies and Ig-new antigen receptors found in cartilaginous fish23, 24. Engineered single-chain variable fragments have been widely used to facilitate generation of Ig-based fusion constructs for phage display, immunohistochemistry, and flow cytometry25. Non-Ig scaffolds have been explored extensively, including LRRs, ankyrin repeats, Zn-fingers, and PDZ domains26–28, but in vitro evolution and structure-based design are often required to achieve desired molecular recognition properties. In fact, VLR-inspired LRR proteins that bind myeloid differentiation protein-2, hen egg lysozyme, and interleukin-6 with affinities ranging from picomolar to micromolar have been rationally designed or isolated from phage libraries28. VLRs, however, benefit from the natural biological diversity inherent in adaptive immunity. VLRs undergo in vivo selection and expansion in an immunological process optimized over millions of years of evolution. Recent technological advances, including development of lamprey adjuvants for improved immune responses to protein antigens and high-throughput display systems for rapid screening, enhance our ability to generate and isolate VLRs against individual protein targets29. However, questions still remain regarding the affinity of VLRBs that can be generated from immune libraries, the diversity of epitopes that VLRBs can recognize, and the contribution of different VLRB modules and features to antigen binding.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), like VLRs, are also composed of LRR subunits, but TLRs function as innate immune receptors for conserved pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPs)30. TLR5, in particular, initiates host-defense in response to the bacterial motor protein flagellin31. Flagellin binds to the TLR5 extracellular domain (ECD), activating cytokine signals via the intracellular Toll/interleukin-1 receptor homology domain31, 32. The TLR5 ECD and intracellular domain are connected by a short single pass transmembrane region. Flagellin tightly binds the TLR5 ECD with Kd estimates in the picomolar range32, 33. To enhance expression and folding for structural studies, zebrafish [Danio rerio (dr)] TLR5N14, was designed containing TLR5 LRRNT to LRR14 fused to a C-terminal LRRCT from VLR34. In co-crystal structures, the ascending lateral face of drTLR5N14 from LRRNT to LRR10 makes extensive contacts with conserved regions of flagellin32.

Although flagellin is the canonical exogenous TLR5 activator, activation by endogenous DAMPs have been implicated in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), periodontitis, and neuropathic pain35–38. A pathway for pain hypersensitivity was recently uncovered in which TLR5 is activated by the alarmin protein high mobility group box-137. The emergence of endogenous DAMPs that activate TLR5 suggests potential therapeutic value in TLR5 antagonists in treating these conditions. Only two TLR5 inhibitors have been reported: the small molecule TH102039 and a commercially available conventional (Ig-based) antibody that binds mouse TLR540. A series of small molecule TLR5 inhibitors for RA treatment have been proposed based on in silico screening, but not validated in biochemical assays41. The lack of effective TLR5 inhibitors may be due, in part, to the high affinity binding between TLR5 and flagellin.

Here we report on the development of three high-affinity VLRB monoclonal antibodies (VLR-1, −2, −9) to the antigen drTLR5N14, a truncated form of the TLR5 ECD from zebrafish. The VLRs were isolated by screening of a yeast surface display (YSD) library constructed from an immunized lamprey. Recombinant monomeric VLR1, 2 and 9 bound to TLR5 in the nM range (Kd = 13 – 130 nM). We tested the ability of VLRs to attenuate TLR5 signaling in cell-based assays using a HEK-derived reporter cell line. We found that the three VLRs ranged in ability to block flagellin binding: VLR1 had no discernible effect, VLR2 a moderate effect, and VLR9 the strongest effect in our assays. Co-crystal structures of VLR-2 and −9 revealed two epitopes on TLR5 targeted by VLRs, both of which overlap with the flagellin binding site, such that flagellin and VLR would not be able to bind TLR5 simultaneously. In contrast to previously published VLR:antigen structures, the VLR LRRNT makes significant contributions to TLR5 binding, thus expanding our understanding of antigen recognition by these unconventional antibodies.

RESULTS

Identification of drTLR5-binding VLRs

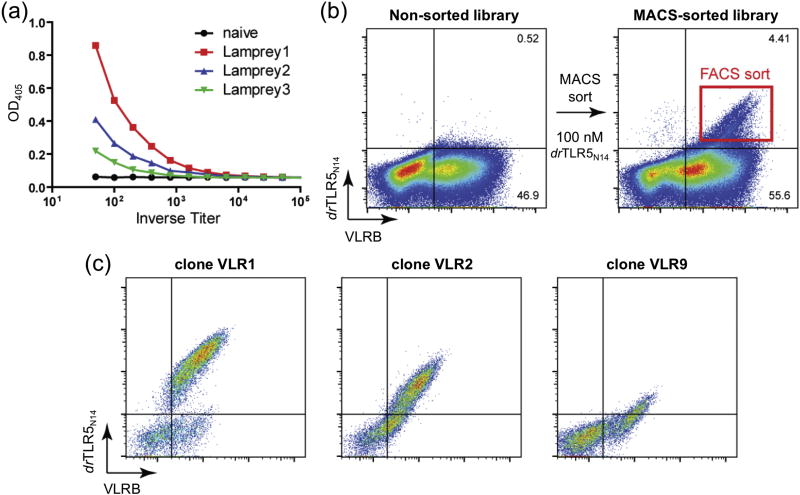

Monoclonal VLRBs specific for drTLR5N14, a zebrafish construct of TLR5, were generated by screening a YSD library constructed from lymphocyte cDNA of immunized lampreys. As in jawed vertebrates, most soluble protein antigens are weakly immunogenic to lampreys and require adjuvants to enhance the immune response. Particulate antigens, such as bacteria, viruses or eukaryotic cells, elicit high-titer VLRB responses10. Therefore, purified recombinant engineered drTLR5N14 protein32, 34 was covalently conjugated to paraformaldehyde-fixed human Jurkat T cells as a carrier to enhance immunogenicity. All three lampreys immunized with the Jurkat T cell conjugates produced VLRBs specific for drTLR5N14 as measured by ELISA (Fig. 1). VLRB genes were PCR amplified from the total lymphocyte cDNA of the lamprey with the highest anti-drTLR5N14 VLRB titer and used to generate a YSD library of 1.1 × 106 VLRB clones (Fig. S1a,b). drTLR5N14 binders were enriched from the YSD library by one round of magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Fig. 1b). Individual VLRB clones from the FACS-sorted library were characterized for drTLR5N14 binding (Fig. 1c and Fig. S1c).

Fig. 1.

Isolation of anti-drTLRN14 VLRB clones from an immune YSD library. (a) VLRB antibody titers elicited by immunization of lampreys with drTLR5N14 were determined by ELISA relative to naive control plasma. (b) Enrichment of drTLR5N14 binders from the YSD library. The unsorted library (left) was first enriched by MACS using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to isolate yeast cells labeled with 100 nM biotinylated-drTLR5. The MACS-enriched library was then sorted by FACS gated on drTLR5N14 and VLRB double positive yeast cells (right). (c) Individual drTLR5-binding clones from the sorted library were evaluated by flow cytometer. Biotinylated-drTLR5N14 and VLRB were detected with SAPE and anti-Myc-Alexa-Fluor 488, respectively.

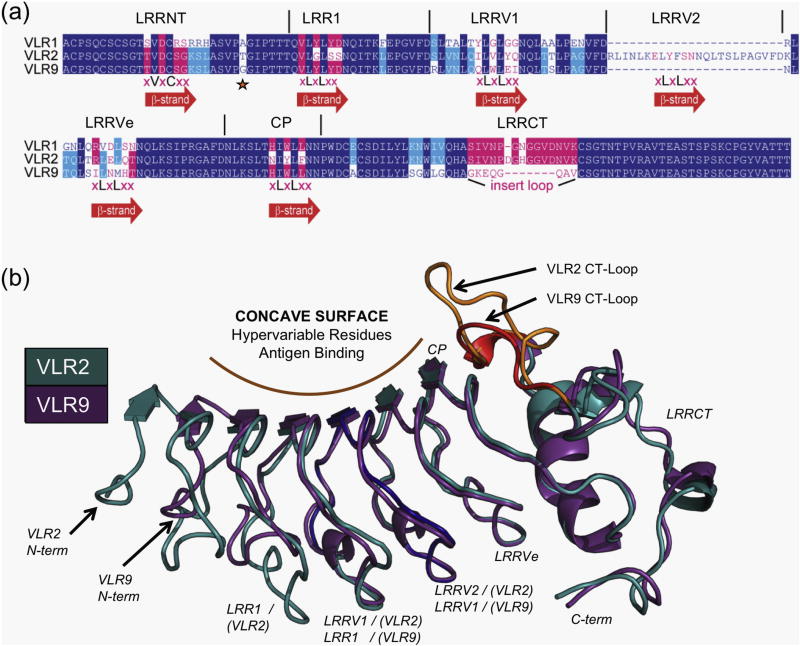

Three representative clones, VLR1, VLR2 and VLR9, were selected for further study based on qualitative binding profiles from FACS and amino-acid sequence analysis. All three clones possessed primary structure motifs typical for VLRs with high amino-acid sequence identity (70–80%) (Fig. 2a and Fig. S2). A few key differences in the sequences illustrate how the VLR framework can be utilized to recognize diverse antigens. First, VLR2 contains one more LRR module (LRRv2) than VLR1 and VLR9. Second, VLR9 has a much shorter CT-loop than VLR1 and VLR2. Finally, we noted significant amino-acid differences in the putative hypervariable antigen-binding β-strands of the three VLRs. Based on these differences, we hypothesized that these VLRs may bind different epitopes on drTLR5N14 antigen.

Fig. 2.

Comparative analysis of VLR antibodies to drTLR5N14. (a) Sequence alignment of VLR-1, −2, and −9 antibodies to drTLR5N14 show high amino-acid identity and overall conservation of LRR motifs that are characteristic of VLR proteins. VLR2 has one more vLRR insert than VLR1 or VLR9. VLR9 has the shortest hypervariable CT-loop insert. The CT-loop sequence alignment is based on the VLR2 and VLR9 crystal structures. Residues on the concave antigen-binding surface are shown in pink text and highlighted in pink, for unique and shared residues, respectively. Residues with side chains not within the antigen-binding face that are conserved or shared are highlighted in dark blue or cyan, respectively. (b) Crystal structures of VLR2 (teal) and VLR9 (purple) superimposed show that they also adopt the overall solenoid shape typical for lamprey antibodies. The VLR2 N-terminus is shifted 7.0 Å from the VLR9 N-terminus by insertion of an extra vLRR domain (dark blue). The CT-loops, a key component in antigen recognition, are highlighted in VLR2 (orange) and VLR9 (red).

To characterize TLR5 binding by VLRs, we recombinantly expressed the LRR domains of VLR1, VLR2, and VLR9 using a baculovirus expression system. All three VLRs purified as monomers on size exclusion chromatography. We observed drTLR5:VLRB complexes in a series of biochemical experiments with the purified proteins, including gel filtration chromatography (Fig. S3). We quantified binding affinities using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and found that VLRs bound drTLR5N14 with dissociation constants in the nanomolar range. VLR9 bound the tightest (Kd = 13 nM), with VLR2 and VLR1 having 3-fold (40 nM) and 10-fold (130 nM) lower affinity, respectively (Table 1, Fig. S4a). The ITC data revealed that each VLR bound monomeric drTLR5N14 with a 1:1 stoichiometry. Binding of drTLR5N14 by VLR1 and VLR9 were enthalpically driven, as indicated by large negative ΔH values. In contrast, VLR2 binding to drTLR5N14 was entropically driven, suggesting a strong hydrophobic effect arising from the release of ordered solvent molecules. Corresponding Kd values quantitated using biolayer-interferometry kinetic measurements were in agreement with the ITC results (Table S1, Fig. S4b).

Table 1.

VLR binding affinity (Kd) for drTLR5N14 and associated thermodynamic parameters by ITC.

| Kd (nM) |

ΔH (cal/mol) |

ΔS (cal/mol/deg) |

N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VLR1 | 130 ± 40 | −19,570 | −34.1 | 0.97 |

| VLR2 | 40 ± 5 | −4665 | 18.2 | 0.95 |

| VLR9 | 13 ± 4 | −13,140 | −7.9 | 1.23 |

HEK-hTLR5 cell activation assays

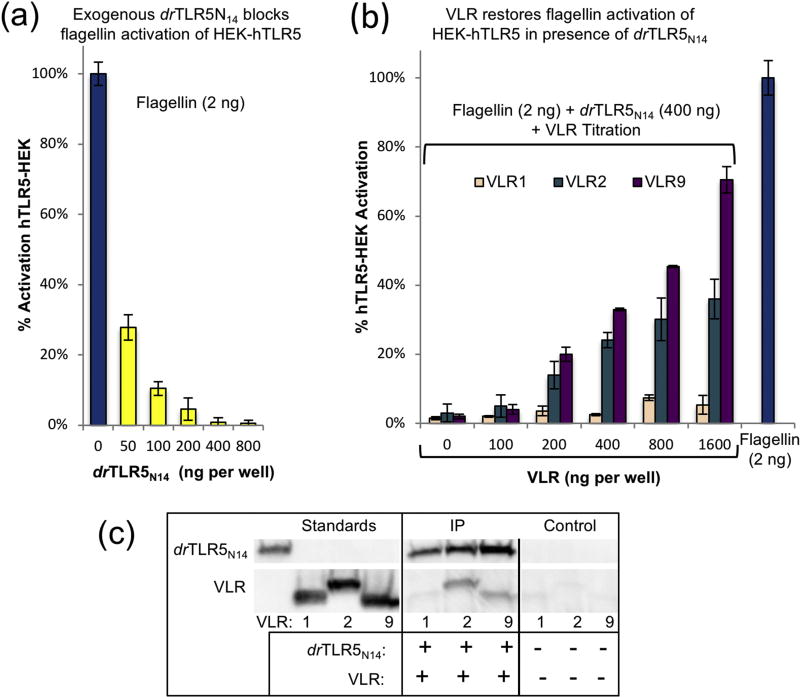

We devised assays using HEK-hTLR5 reporter cells to determine if these VLRs alter flagellin binding to TLR5. HEK-hTLR5 is an established commercially available HEK293-derived cell line stably co-transfected with human TLR5 and an NF-κB inducible secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter gene (Fig. S5a). For these experiments, we treated HEK-hTLR5 cells with combinations of recombinant endotoxin-free VLR, drTLR5N14 and recombinant Salmonella typhimurium flagellin. First, we tested flagellin, a known TLR5 activator, in the HEK-hTLR5 SEAP signaling assay and observed a robust signal for flagellin (2 ng) (Fig. 3a, blue bar, Fig. S5b). Purified drTLR5N14 protein was then tested in combination with flagellin to determine if exogenous zebrafish TLR5 protein (drTLR5N14) could compete with hTLR5 on the cell surface for flagellin binding, thereby inhibiting HEK-hTLR5 activation (Fig. S5c). Varying amounts of drTLR5N14 were tested (0 – 800 µg), and we determined that 400 ng of drTLR5N14 effectively blocked any activation by 2 ng flagellin in HEK-hTLR5 assays (Fig. 3a). In subsequent assays, we tested the ability of each VLR to bind drTLR5N14 in the presence of flagellin, thereby increasing the effective concentration of flagellin in solution to activate cell surface hTLR5 (Fig. S5d). VLR9 showed the largest effect, where 70% of the flagellin signal was restored by VLR9 (1.6 µg) in the presence of inhibitory drTLR5N14 (400 ng, Fig. 3b). VLR2 had moderate effects, restoring 36% of activity of flagellin under the same conditions. VLR1 had no discernable impact on signaling up to 1.6 µg. We tested additional combinations of proteins as controls, including each VLR only, drTLR5N14 only, VLR/drTLR5N14, and VLR/flagellin. The controls confirmed that SEAP signaling from HEK-hTLR5 cells was not activated by individual VLRs, drTLR5N14, or VLR/drTLR5N14 combinations in the absence of flagellin. Furthermore, in the absence of drTLR5N14, these VLRs had no effect on HEK-hTLR5 activation by flagellin, suggesting that they are specific for drTLR5. Viability assays using the cell proliferation reagent WST-1 confirmed that flagellin, drTLR5N14, or VLRs, alone or in combination, did not kill the hTLR5-HEK cells (Fig. S6). To confirm TLR/VLR complex formation in the assay system, we performed a pull-down utilizing fusion-tagged drTLR5-His6-StrepII and VLR-His6 (Fig. 3c). For these experiments, magnetic strep-tactin beads were utilized to purify drTLR5N14 protein complexes from HEK-hTLR5 cell culture. Western blot analysis using an anti-His antibody showed that VLR2 and VLR9, but not VLR1, co-purified with drTLR5, consistent with the higher overall affinities of VLR2 and VLR9 for drTLR5 (Table 1) and the much faster off-rate of VLR1 for drTLR5N14 (Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

HEK-hTLR5 assays. (a) In a reporter cell-based assay, hTLR5-HEK activation by flagellin is blocked by addition of exogenous drTLR5. HEK-hTLR5 cells are HEK293-derived cells stably co-transfected with hTLR5 and an NF-κB-inducible SEAP reporter gene. HEK-hTLR5 cells were incubated with endotoxin-free flagellin (2 ng, blue bar) or PBS in Quanti-Blue SEAP detection media for 16 hours. HEK-hTLR5 cells in Quanti-Blue SEAP detection media were incubated with flagellin (2 ng) and exogenous drTLR5N14 (0 to 800 ng). Exogenous drTLR5N14 inhibits flagellin activation of SEAP signaling in HEK-hTLR5 reporter cells in a dose-dependent manner (yellow bars). SEAP was detected in the culture media by measuring absorbance at 620 nm. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. Activation was quantitated by measuring absorbance of SEAP in the culture media (A620nm). Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. (b) VLR9 decreases the inhibitory effect of exogenous drTLR5N14 (200 ng) on 2 ng flagellin-activated hTLR5-HEK, restoring up to 70% activation (purple bars), compared to flagellin-activated cells without exogenous drTLR5N14 (blue bar, left). Similarly including VLR2 in the assay restores up to 30% activity in the drTLR5-flagellin-HEK-hTLR5 assay (teal bars). In contrast, increasing amounts of VLR1 have no effect on drTLR5N14 inhibition of flagellin/hTLR5-HEK SEAP signaling (peach bars). (c) Immunoprecipitation shows exogenous drTLR5N14 complexes with VLR2 and VLR9, but not VLR1, in HEK-hTLR5 assays. Immuno-precipitation experiments were performed using drTLR5-His6StrepII (8 µg/mL) and His6-VLR-1, −2, or −9 incubated with HEK-hTLR5 cells for 16 hours. Exogenous drTLR5N14 was pulled from cell media supernatant using magnetic strep-tactin beads. Eluted samples were analyzed on Western Blot using anti-HIS-HRP antibody (1:5000). Molecular weight standards (left) and samples lacking drTLR5N14 (right, negative control) are shown.

VLR2 and VLR9 crystal structures

VLR2 and VLR9 crystals were grown by vapor diffusion and X-ray crystal structures were determined at very high resolution, 1.1 Å and 1.6 Å, respectively (Table 2). Both proteins have the characteristic solenoid structures of VLRs, and closely superimpose with each other (RMSD 0.5 Å, 119 Cα atoms aligned) (Fig. 2b). The short CT loop in VLR9 (residues 152–159) is well tolerated in the structure with minor shifts in LRRCT compared to the VLR2 structure. In the VLR2 structure, insertion of LRRv2 shifts the LRR register and extends the putative antigen-binding pocket without perturbing the overall fold. Geometric analysis of the solenoids using ConSole42 revealed similar curvatures for VLR2 and VLR9 (209° and 207°, respectively). Overall, the apo crystal structures reveal that sequence variations in VLR2 and VLR9 are well accommodated within in the modular LRR framework.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for VLR and TLR5 crystal structures

| Structure | VLR2 (6BXD) |

VLR9 (6BXE) |

drTLR5N14 + VLR2 (6BXA) |

drTLR5N14 +VLR9 (6BXC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Data Collection | ||||

|

| ||||

| Beamline | SSRL 12-2 | SSRL 9-2 | APS 23-IDD | APS 23-IDD |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.88557 | 0.97946 | 1.03320 | 1.03320 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 50.0-1.10 (1.12-1.10) | 50.0-1.65 (1.68-1.65) | 50.0-2.30 (2.35-2.30) | 50.0-2.5 (2.54-2.50) |

| Space Group | P21212 | P61 | P21212 | P1 |

| Unit Cell (Å;°) | a=63.1,b = 40.9, c = 74.8 | a=b=75.5, c=99.3 | a=98.7, b=112.1, c=148.4 | a=69.3, b=69.4, c=84.5; a= 112.1, p=112.1, y=100.8 |

| Asymmetric unit | 1 VLR2 | 2 VLR9 | 2 × (TLR5/VLR2) | 2 × (TLR5/VLR9) |

| # Observations | 709,470 (5790) | 697,431 (17858) | 415,952 (8032) | 78,109 (3008) |

| # Unique Reflections | 74,681 (2632) | 38,111 (1669) | 72,974 (3213) | 42,427 (1741) |

| Redundancy | 9.5 (2.2) | 18.3 (10.7) | 5.7 (2.5) | 2.7 (1.7) |

| Completeness(%) | 95.2 (68.8) | 98.9 (86.6) | 99.2 (88.0) | 88.9 (46.0) |

| <I/σi> | 33.5 (1.7) | 38.2 (1.9) | 20.2 (1.3) | 14.6 (1.4) |

| Rmergeb | 0.10 (0.47) | 0.09 (0.93) | 0.09 (0.93) | 0.10 (0.52) |

| Rpimc | 0.03 (0.37) | 0.02 (0.28) | 0.04 (0.53) | 0.05 (0.33) |

| CC1/2a | 0.91 (0.69) | 0.95 (0.68) | 0.89 (0.45) | 0.92 (0.71) |

|

| ||||

| Refinement | ||||

|

| ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 37.4-1.10 (1.12-1.10) | 35.3-1.65 (1.70-1.65) | 49.5-2.30 (2.33-2.30) | 45.3-2.50 (2.56-2.50) |

| # Reflections- work | 70,893 (1685) | 36,217 (2512) | 69,307 (2516) | 39,737 (1606) |

| # Reflections- test | 3716 (99) | 1854 (112) | 3616 (98) | 2086 (75) |

| Rcryst (%)e | 17.5 (29.4) | 15.4 (22.8) | 18.5 (30.3) | 23.0 (30.6) |

| Rfree (%)f | 17.9 (30.8) | 17.8 (24.7) | 21.8 (32.7) | 27.0 (31.9) |

| Refined B Average (Å2) | 19 | 29 | 64 | 68 |

| Wilson B-value (Å2) | 13 | 22 | 44 | 46 |

| Residues | 192 | 326 | 1268 | 1213 |

| Waters | 268 | 241 | 339 | 121 |

|

| ||||

| RMSD ideal geometry | ||||

|

| ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

|

| ||||

| Ramachandran (%)g | ||||

|

| ||||

| Favored | 95.9 | 95.7 | 96.1 | 94.9 |

| Allowed | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 5.0 |

| Outliers | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

Numbers in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

Rmerge=ΣhklΣi |Ihkl,i − <Ihkl>|/ΣhklΣi Ihkl,l where Ihkl,i is the scaled intensity of the Ith measurement of reflection hkl, <Ihkl> is the average intensity for that reflection.

Rpim is a redundancy-independent measure of the quality of intensity measurements. Rpim = Σhkl(1/(n−1))1/2 Σi |Ihkl,i − <Ihkl>|/ΣhklΣiIhkl,l, where Ihkl,i is the scaled intensity of the ith measurement of reflection hkl, <Ihkl> is the average intensity of reflection hkl, and n is the redundancy.

CC1/2 = Pearson Correlation Coefficient between two random half datasets.

Rcryst = Σhkl | Fo − Fc | Σhkl | Fo | × 100

Rfree was calculated as for Rctyst, but on a test set comprising 5% of the data excluded from refinement.

Values calculated using Phenix.

Two dr TLR5N14 epitopes recognized by VLRs

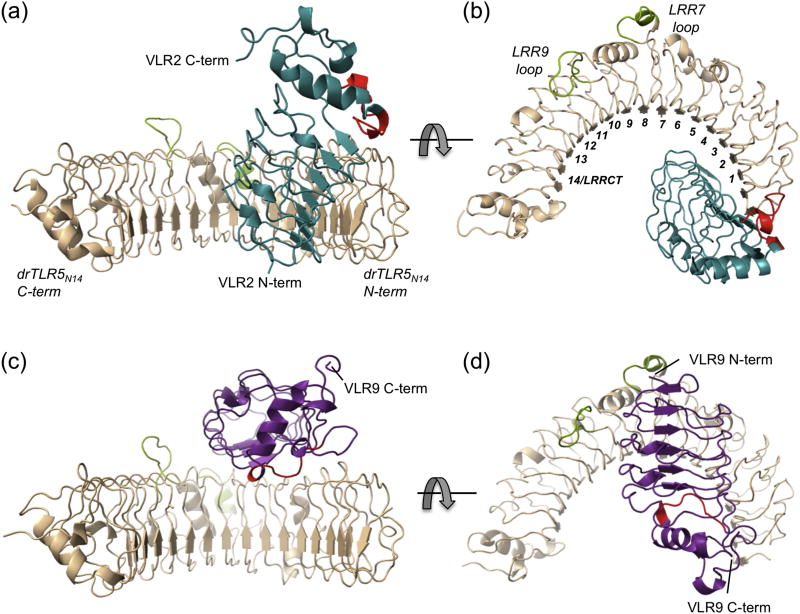

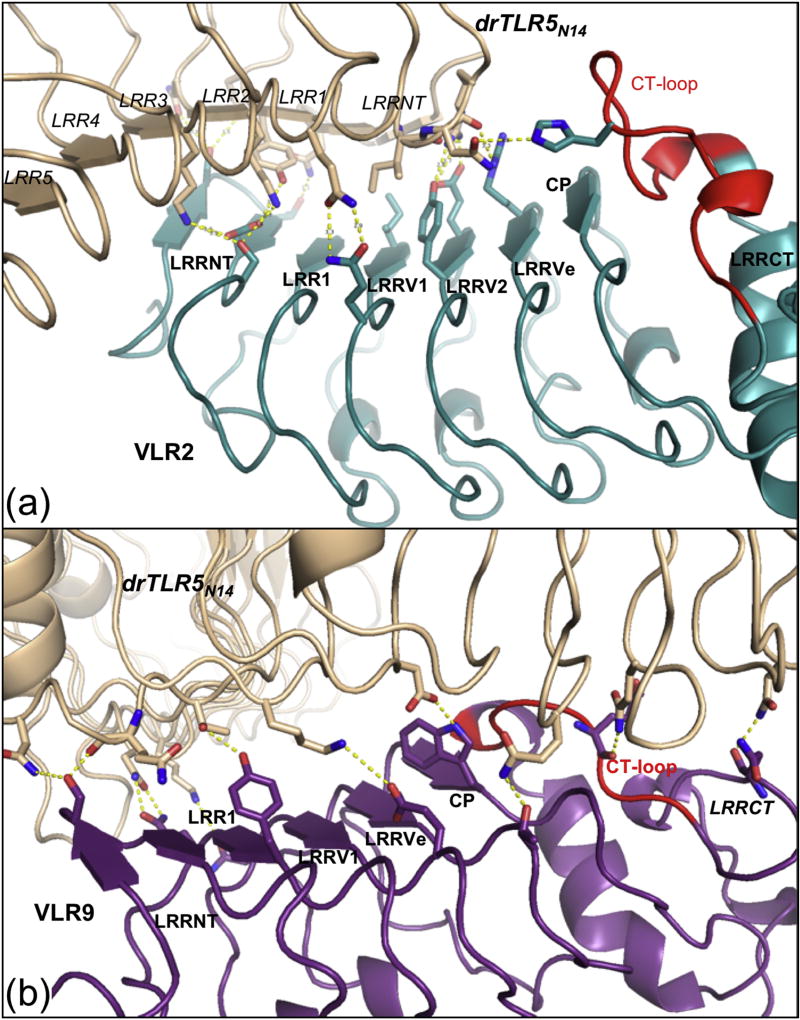

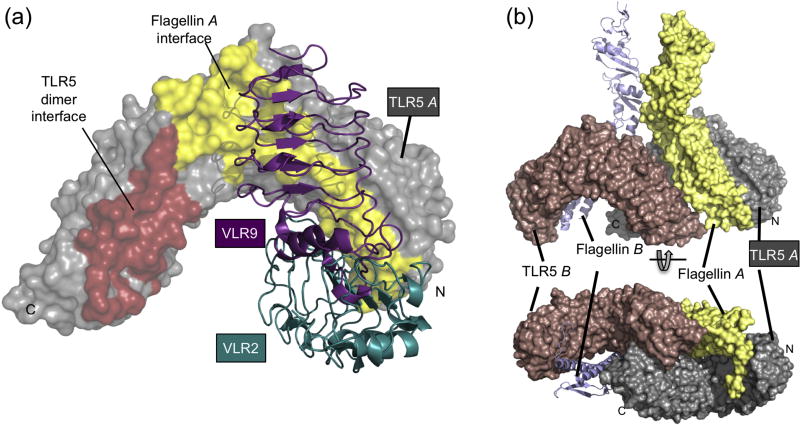

To identify the antigenic sites on drTLR5N14 recognized by these VLRs, we determined crystal structures of the drTLR5:VLR2 and drTLR5:VLR9 complexes (Table 2). The structures revealed the VLRs bind to two different epitopes on drTLR5. The concave surface near the drTLR5N14 N-terminus serves as the epitope for VLR2, whereas VLR9 envelops the ascending lateral face of drTLR5N14 between the central and N-terminal regions (Fig. 4). VLR2 primarily contacts the drTLR5N14 LRRNT and LRR1–3 β-strands on the concave surface of the antigen (Fig. 5a). The concave surfaces of drTLR5N14 and VLR2 clasp each other in a handshake-like configuration, with the β-strands from each protein rotated approximately 50° relative to each other. In contrast, VLR9-LRRNT binds near the apex of the drTLR5N14 horseshoe, adjacent to LRR9-loop (271–280). VLR9 then wraps along drTLR5N14 lateral face towards the N-terminus, such that VLR9-LRRCT contacts drTLR5N14-LRRNT (Fig. 4d and Fig. 5b). Although the binding sites differ, there is overlap such that VLR2 and VLR9 could not simultaneously bind drTLR5N14 (Fig. 6 and Fig. S7). This then is the first demonstration that VLRBs isolated from an immunized lamprey can target multiple epitopes on a protein antigen.

Fig. 4.

Two different epitopes on drTLR5N14 (beige) are recognized by VLR2 (teal) and VLR9 (purple). (a) The N-terminal concave surface of drTLR5N14 is the binding site for VLR2 as viewed into the concave surface of drTLR5N14 and (b) rotated 90° viewed along ascending lateral face of the drTLR5N14 horseshoe with LRR domains numbered. (c,d) VLR9 binds the lateral surface of drTLR5N14 as shown in the same orientations as A,B. VLR CT-loop inserts are highlighted in red and the two long LRR loops in drTLR5N14 are indicated in green.

Fig. 5.

drTLR5N14 (beige) binding interfaces with VLRs. (a) VLR2 (teal) contacts with drTLR5N14 are distributed along the VLR concave surface, with little involvement from the CT-loop (red). (b) VLR9 (purple) contacts with drTLR5N14 are also distributed along the VLR concave surface.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of VLR binding sites to the protein interfaces observed in flagellin-bound drTLR5N14 crystal structure. (a) Superposition of VLR2 (teal) and VLR9 (purple) bound to TLR5 (grey) reveals that binding is mutually exclusive. VLR2 and VLR9 bind different, but partially intersecting regions on drTLR5. The flagellin binding interface on drTLR5N14 (yellow surface) involves regions recognized by both VLRs, indicating that flagellin and VLR binding are also mutually exclusive. Neither VLR would interfere with the TLR5-TLR5 dimer interface (rose surface) observed in the drTLR5-flagellin bound crystal structure. (b) Interfaces in the drTLR5N14:flagellin dimer (PDB 3V4732) , with surfaces colored: TLR5 A, grey; TLR5 B, pink; Flagellin A, yellow. Flagellin B is shown as light blue ribbons. View rotated 90° (bottom).

Analyzing the binding interfaces in our structures, we found that VLR2 and VLR9 bury relatively large surface areas on drTLR5N14 (742 Å2 and 853 Å2, respectively, Table 3). These large antigen surface areas are consistent with the tight binding of drTLR5. VLR9, despite having a smaller concave binding site, buries more overall surface area on drTLR5N14 than VLR2, and has 3-fold higher affinity for drTLR5N14 than VLR2. Compared to other VLR structures, VLR2 and VLR9 have the largest buried surface areas thus far observed (Table 3), which may be due in part to having only three other crystal structures of VLR in complex with a protein antigen available for comparison.

Table 3.

Buried surface areas and Kd for VLR:antigen complexes

| VLR | Antigen | Kd (nM) |

PDB ID | Buried surface area (Å2) | Buried surface area by VLR region (Å2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen | VLR | LRRNT | Middle | LRRCT (CT-loop) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| VLR1 | drTLR5N14 | 130 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | |

|

| ||||||||

| VLR2 | drTLR5N14 | 40 | 6BXD | 742 | 749 | 266 | 434 | 49 (49) |

|

| ||||||||

| VLR9 | drTLR5N14 | 13 | 6BXE | 853 | 845 | 127 | 569 | 149 (100) |

|

| ||||||||

| VLR4 | BclA | 600 | 3TWI13 | 432 | 428 | 19 | 286 | 123 (123) |

|

| ||||||||

| VLRb.2D | HEL | 430* | 3G3A14 | 679 | 665 | 0 | 329 | 336 (330) |

|

| ||||||||

| VLRA.R2.1 | HEL | 0.18 | 3M1818 | 698 | 747 | 26 | 493 | 228 (220) |

|

| ||||||||

| VLRB. aGPA.23 | Thomsen-Friedenreich glycan | 45000† | 4K7916 | 251 | 301 | 0 | 238 | 63 (63) |

|

| ||||||||

| RBC36 | H-trisaccharide | 8300 | 3EJ612 | 249 | 290 | 0 | 229 | 61 (61) |

|

| ||||||||

| RBC36 | α1–2 Fucosyl-lactose | 57100 | 5UFF11 | 214 | 269 | 0 | 210 | 59 (59) |

|

| ||||||||

| O13 | H-trisaccharide | 2600 | 5UF111 | 259 | 290 | 0 | 230 | 60 (60) |

|

| ||||||||

| O13 | LNnT | 160000 | 5UF411 | 280 | 318 | 23 | 247 | 48 (48) |

VLRb.2D as identified from lamprey. Random mutagenesis was used improve VLRb.2D in vitro, resulting in Mut13 Kd=34 nM.

Calculated as Kd=K−1, with K measured by ITC16.

N.A. – not available.

The structure of drTLR5N14 in the two VLR complexes is essentially unchanged from that of drTLR5N14 in complex with the endogenous ligand flagellin (RMSD 0.46 – 0.68 Å for all 441 Cα atoms aligned, Fig. S8). Our co-crystal structures show that VLR2 and VLR9 binding sites on drTLR5N14 both include regions required for flagellin binding, suggesting that drTLR5N14 would not be able to simultaneously bind the physiological ligand flagellin at the same time as either of these VLRs (Fig. 6). The overlap with the flagellin binding site then provides the structural explanation for VLR2 and VLR9 competition with flagellin binding to drTLR5N14 in the HEK-TLR5 cell assays.

These VLRs appeared to be selective for drTLR5 as they did not inhibit flagellin activation of HEK-hTLR5 in reporter cell assays. We therefore analyzed our VLR:TLR co-crystal structures to investigate the structural basis for this apparent species specificity. We used the drTLR5N14 crystal structure as a template to construct a homology model of hTLR5. We then superimposed each drTLR5N14:VLR co-crystal structure onto the hTLR5 model and analyzed putative clashes between VLR and hTLR5. We observed substantial clashes that would likely preclude binding of either VLR to hTLR5 (Table S2). In the case of VLR2, we noted several particularly severe clashes between VLR2 LRRNT backbone and side chains (Ser29, Gly30, Thr32) and hTLR5 side chains (Ile30, Arg50) that do not occur with corresponding drTLR5 side chains (Asn31, Tyr51, respectively). In our hTLR5:VLR9 model, at least four hTLR5 side chains clashed with VLR9 side chains, including hTLR5 Ile264 which clashed with VLR9 Gln52, whereas the corresponding residue in drTLR5 (Asn268) formed a salt bridge with VLR9. Overall, these models provided a possible structural basis for the species specificity of the VLRs observed in our cell-based assays.

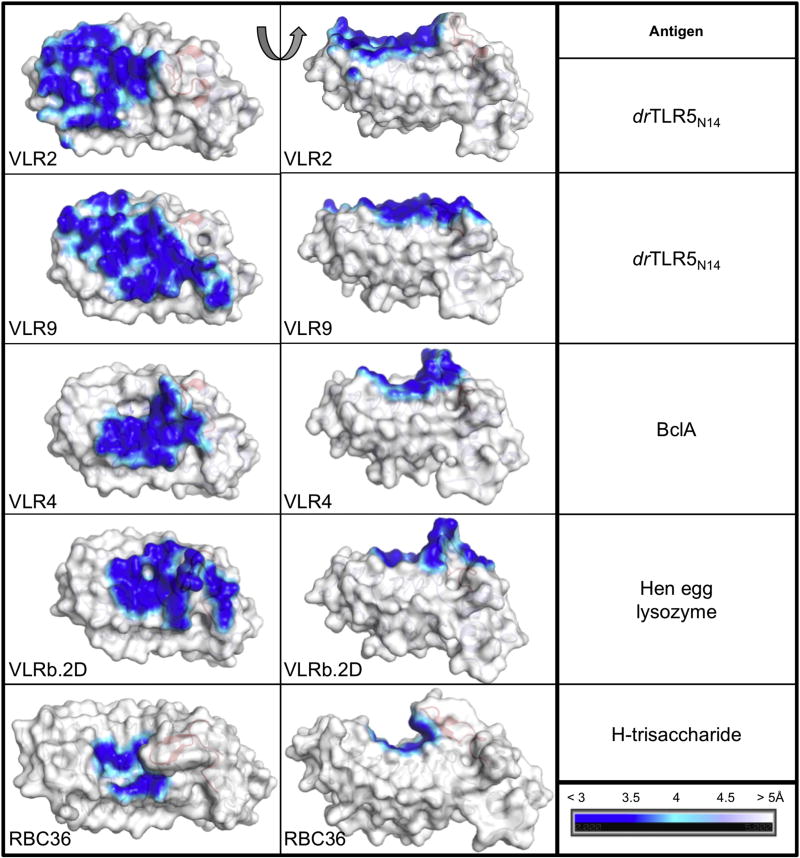

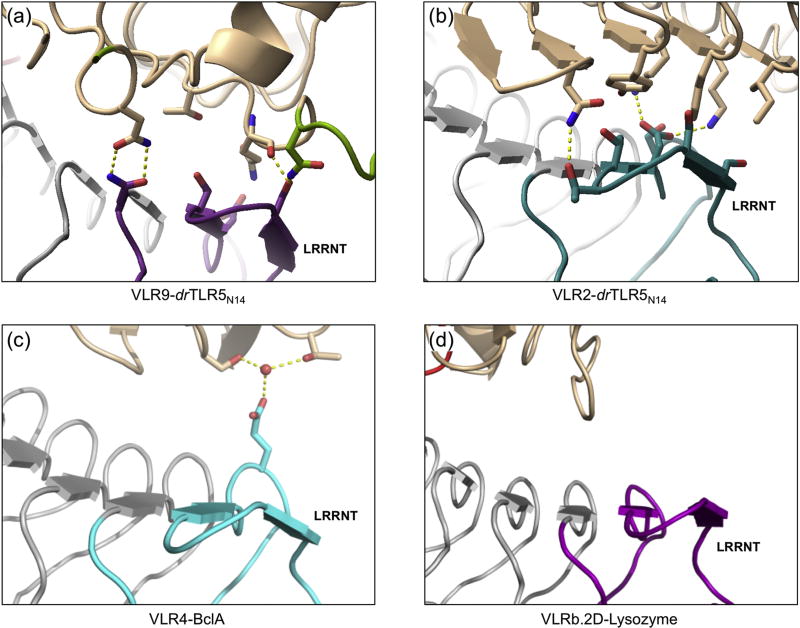

Antigen recognition by VLR

In order to expand our understanding of VLR-antigen recognition, we analyzed the relative contributions of VLR regions to antigen interfaces. Here we found that VLR2 and VLR9 draw from interactions throughout their concave surfaces (Fig. 7). The VLR contacts with drTLR5N14 were distributed extensively along the concave surface relative to other VLR:antigen structures. LRRNTs of VLR2 and VLR9 make sizeable contributions to the antigen binding surfaces in our structures, whereas in previously published structures, the antigen binding surfaces were almost exclusively formed by LRRV and LRRCT, with little or no contribution from LRRNT (≤ 7% of overall buried surface area, Table 3 and Fig. S9). LRRNTs of VLR2 and VLR9 make a number of specific contacts with TLR5 that include hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic packing interactions (Fig 8a, b). These observations are in stark contrast to the VLR4:BclA and VLRb.2D:lysozyme structures, where contacts from LRRNT were limited to a water-mediated hydrogen bond in VLR4-BclA (Fig. 8c, d). Interestingly, the LRRNTs of VLR2 and VLR9 are almost completely identical with just one amino-acid difference (Thr47 and Gly45, respectively), which is located on the convex surface and does not interact with drTLR5N14 (Fig. 2a). Conserved residues in LRRNTs of VLR2 and VLR9 bind different sites on TLR5, suggesting that the context of LRRNT within the VLR framework is important for antigen recognition. We found that LRRCTs of VLR2 and VLR9 contribute a smaller fraction to the antigen interface than observed in previously reported VLRB:antigen complexes (Fig. S9). In this analysis, the CT-loops were primarily responsible for the LRRCT surface area contribution (Table 3). The LRRNT of VLR2 and VLR9 contribute a substantially larger fraction to the antigen interface, thereby offsetting the decreased contribution by LRRCT to the antigen interface. Overall, these results reveal that specific antigen interactions can be distributed throughout the VLR hypervariable convex surface, with varying contributions from LRRNT, middle LRRs, and LRRCT.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of interfaces for all published VLRB:protein co-crystal structures and RBC36:H-trisaccharide as a representative of glycan binding VLRBs. VLR surfaces are colored by proximity to antigen from blue to white. VLR ribbons are shown underneath the surface with CT-loop shown in red. Left panels show views looking directly into the concave surface, center panels are rotated 90° looking along the edge of the concave surface. The corresponding antigens are listed in the column on the right. VLRs from the following co-crystal structures are shown from top to bottom: VLR2/drTLR5, VLR9/drTLR5, VLR4/Bcl13, VLRb.2D/hen egg lysozyme14, RBC36/H-trisaccharide12.

Fig. 8.

Detailed views of VLRB-LRRNT interactions with corresponding antigens show extensive LRRNT-antigen contacts for (a) VLR2-drTLR5N14 and (b) VLR2-drTLR5N14. (c) A single side chain of VLR4-LRRNT makes water-mediated hydrogen bonds with antigen BclA. (d) VLRb.2D-LRRNT has no contacts with hen egg lysozyme. Antigens shown as beige ribbons, VLR-LRRNTs shown as colored ribbons, and VLR middle and LRRCT as grey ribbons. Interface residues are shown as colored sticks. For clarity, only select VLR-drTLR5N14 interface residues are shown.

DISCUSSION

The findings here represent the first example of multiple high-affinity VLRB epitopes on a single protein antigen, and which also include biologically functional regions, such as the flagellin binding site on TLR5. Previously reported monomeric VLRB antibodies were relatively low affinity with Kd’s in the micromolar to high nanomolar range. Here we show that rare high affinity clones that bind protein targets in the low nanomolar range can be isolated by yeast display screening of immune libraries. In fact, two of the VLRs that we isolated could compete with the extremely tight (picomolar) flagellin binding to drTLR5, as demonstrated by our results from cell-based assays. The VLRs had differing abilities to interfere with drTLR5N14:flagellin interaction, where VLR9 had the greatest effect, VLR2 a moderate effect, and VLR1 had no discernable effect.

As lamprey immunizations take weeks and require a special aquaculture facility, this could potentially limit the broad use of VLRs as antibody alternatives. To circumvent the need for immunization, non-immune VLR libraries have indeed been used to isolate binders to protein and carbohydrate antigens. In the non-immune approach, cDNA from ~100 naïve lampreys was pooled to generate a large library of >108 clones43. Notwithstanding, immunization enabled us to isolate diverse clones with high affinity for drTLR5N14 by screening a 100-fold smaller library (106 VLRB clones) derived from a single lamprey. Therefore, a non-immune library was not required to screen for TLR5 binding; however, the polyclonal VLRB response of all three immunized lampreys suggests that at least most lampreys have TLR5 binders in their repertoire. Due to the lack of in vivo clonal expansion, a non-immune library would likely require additional rounds of screening to obtain the same frequency of binders as the immune library, and it is not yet clear if the current non-immune VLR libraries would match the epitope diversity and affinity of immune libraries.

Recent studies suggest that activation of human TLR5 by endogenous DAMPS is involved in several pathologies, including RA and neuropathic pain. Synovial fluid from RA patients contains an, as yet unidentified, TLR5 activator36, 38. Joint swelling in mice with collagen-induced arthritis was decreased by treatment with an Ig-based neutralizing antibody against murine TLR535. TLR5 activation by high mobility group box-1 protein leads to neuropathic pain37. A current challenge in innate immunity is understanding how receptors distinguish and respond to pathogenic and endogenous activators. In the case of TLR5, although flagellin is the canonical activator, other activators have been identified. Profilin derived from Toxoplasma gondii was recently discovered to activate human TLR544. The TLR5 activator CBLB502 (entolomid) is an engineered flagellin derivative that is in clinical trials as a radioprotective treatment45, 46. The ability to isolate VLRs that target various epitopes opens the door to differentiate the roles for PAMPs and DAMPs in physiological and pathophysiological settings. An eventual goal could be to block TLR5 activation by DAMPs, while maintaining the innate immune response of TLR5 to bacterial flagellin. VLRs could be utilized to identify target sites for this purpose as well as to develop research tools for cell-based studies. To test this possibility, future studies are needed to develop and characterize VLRs that target human TLR5.

Our results address several fundamental questions about VLRB-antigen interactions. Analysis of co-crystal structures with drTLR5N14 revealed that contacts throughout the concave surface of VLR have a significant role in antigen binding (Fig. 7). All of the previous VLRB-antigen structures suggested that the LRRCT and the more C-terminal β-strands were the most important for binding. In fact, the LRRCT was proposed to be the “HCDR3-equivalent” of Ig antibodies. Previous structures suggested that the LRRNT had little or no role in antigen binding, although sequence analysis showed that it was highly diverse. Recent work on glycan-specific VLRs demonstrated that, while LRRCT made critical contacts with conserved antigen cores, selectivity between closely related glycans was achieved by contacts with the central β-strands11. Our work here now shows two examples of LRRNT having a significant role in antigen binding, including contributing over one-third of the antigen-binding surface in the VLR2 interaction (Fig. S9). The VLR9 structure contains a short LRRCT insert that had not been structurally characterized previously, which contributes to formation of a relatively flat antigen-binding surface that has the largest buried surface area of any VLR analyzed so far.

Together, these findings highlight the potential of the VLR system to rapidly generate high affinity antibodies to multiple epitopes on a target antigen, by combining high-throughput yeast display with immunization and in vivo expansion of antigen-reactive VLRB clones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

VLR Development

Sea Lamprey

Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) larvae 12–15 cm in length were captured by commercial fishermen (Lamprey Services, Ludington, MI) and maintained in sand-lined, aerated aquariums at 16–20 °C. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University.

Antigen Formulation

For immunization, recombinant drTLR5N14 was covalently conjugated to fixed Jurkat T cells as a carrier to enhance the immune response. Jurkat T cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Cellgro) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For conjugation, 108 Jurkat T cells were washed three times with PBS, then fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences). The following day, the cells were washed in 20 mM MES, pH 5.5, and activated for amine conjugation by treatment with (1-ethyl-3-(–3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride/N-hydroxysuccinimide (EDC/NHS, ThermoFisher) for 20 min at room temperature, then washed briefly with PBS. 0.5 mg/mL drTLR5N14 in PBS was immediately added to the EDC/NHS-activated cells and incubated for 3 hrs at room temperature on a rotating mixer. After the incubation, the cells were washed with PBS/10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and the drTLR5-conjugated Jurkat cells were stored at 4 °C until needed for immunization.

Immunization

Lamprey larvae were sedated with 0.1 g/L tricainemethanesulfonate (Tricaine-S; Western Chemical, Inc.) and then injected with 107 drTLR5-conjugated Jurkat cells in 30 µL of PBS, corresponding to approximately 50 µg recombinant drTLR5. Lampreys were immunized a total of three times at two week intervals. Two weeks after the final immunization, lampreys were euthanized with 1g/L Tricaine-S and ~200 µL of blood was collected into 200 µL of PBS with 30 mM EDTA added as an anticoagulant. The blood was layered on top of 55% Percoll, centrifuged at 400xg for 5 minutes to separate erythrocytes in the pellet, leukocytes at the Percoll interface, and plasma in the supernatant. VLRB antibody titers were determined using ELISA from plasma buffered with 20mM MOPS pH 7.2 and 0.025% sodium azide. Leukocytes were collected from the Percoll interface, mixed with stabilization reagent, RNAlater (ThermoFisher), and stored at −80 °C for VLRB cDNA library cloning.

ELISA

Plates coated with recombinant drTLR5N14 (5 µg/ml) were blocked with 2% skim milk in TBST (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.5) before incubation with serial dilutions of plasma from immunized or naïve lamprey. VLRB antibodies were detected using anti-VLRB mouse mAb (4C4)1, followed by alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG polyclonal Ab (Southern Biotech). Wells were washed 3x with TBST after each staining step. Sample wells were incubated with AP substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min, after which the reaction was stopped by adding 3 M NaOH. Absorbance at 405nm was measured using a plate reader (Molecular Devices) and graphed using GraphPad PRISM software.

VLRB cDNA Library Cloning

RNA from total leukocytes was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and oligo-dT priming. VLRB transcripts were amplified from cDNA by nested PCR using KOD hot-start DNA polymerase (EMD-Millipore). For the first round of PCR, primers corresponding to conserved VLRB 5’-and 3’-untranslated regions (CTCCGCTACTCGGCCTGCA and CCGCCATCCCCGACCTTTG, respectively) were used. For the second round of PCR, the VLRB antigen-binding domain, without the signal peptide and stalk region, was amplified using primers for LRRNT (GCATGTCCCTCGCAGTG) and LRRCT (CGTGGTCGTAGCAACGTAG) plus an additional 50 base pairs corresponding to the YSD vector, pCT-ESO-BDNF. The pCT-ESO-BDNF plasmid was a gift from Dr. Eric Shusta at the University of Wisconsin-Madison47. The YSD plasmid contains the Aga2p yeast surface protein under the control of a galactose-inducible promoter. Brain-derived neurotropic factor is fused to the C-terminus of Aga2p by a glycine linker sequence and a Myc-epitope tag is encoded at the C-terminus of the vector. The vector was digested with NheI, NcoI and BamHI (New England Biolabs) to linearize the plasmid and remove the BDNF insert. VLRB PCR products were gel purified from 1% agarose in preparation for cloning by in vivo homologous recombination in yeast.

For VLRB library transformation, yeast cells were grown to log-phase in YPD media at 30 °C (~1 OD600). Yeast cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1,000xg, washed in Milli-Q water, resuspended in 10 mM Tris, 10 mM DTT, 100 mM Lithium Acetate, pH 7.6, and incubated for 20 min at 225 rpm and 30 °C. After incubation, cells were washed in Milli-Q water and resuspended in 1 M sorbitol at 1×109 cells/ml. 200 µl of yeast cells were mixed with 1 µg of digested vector and 2 µg of purified VLRB PCR product and added to a 0.2 cm electroporation cuvette on ice. The yeast cells were electroporated at 2.5 kV (12.5 kV/cm) using a Bio-Rad Micropulser. After electroporation, the yeast cells were incubated in a 1:1 mixture of 1 M sorbitol and YPD media for 1 hr at 30 °C, then transferred to SD-CAA media. A small aliquot of the electroporated yeast cells was serially diluted and plated on SD-CAA agar plates to calculate the total number of transformants (1.1 × 106 VLRB clones). Aliquots of the yeast library were stored at −80 °C in 15% glycerol.

Yeast Surface Display and VLRB Identification

drTLR5N14 was biotinylated with EZ-link NHS-LC-LC-biotin (ThermoFisher) at a 5:1 biotin to protein molar ratio for 20 min at room temperature. Unreacted NHS-LC-LC-biotin was removed using a Zeba desalting spin column (ThermoFisher) pre-equilibrated with PBS. Biotinylated drTLR5N14 was used to enrich for binders from the VLRB yeast display library by MACS and FACS. An overnight yeast culture was diluted into fresh SD-CAA and grown for 3 hours at 30 °C. Cells were harvested, resuspended in SG-CAA media to induce VLRB expression, and subsequently grown for 48 hours at 20 °C. The induced VLRB YSD library was washed in staining buffer (PBS pH 7.4, 1% BSA), incubated with 100 nM biotinylated drTLR5N14 for 30 minutes at room temperature, and then washed with ice-cold staining buffer three times. Streptavidin-conjugated magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech) were added to the washed yeast cells in 1 ml of staining buffer and incubated at 4 °C on a rotating mixer for 30 min. After incubation, the yeast cells were added to an LS column on a MidiMACS magnet (Miltenyi Biotech) for enrichment by positive selection. After washing, the antigen-captured yeast cells were eluted from the LS column in SD-CAA media and cultured at 30°C. The MACS-sorted library was then subsequently enriched by FACS. Yeast cells were labeled with 100 nM drTLR5, then incubated with 5 µg/mL mouse anti-Myc-epitope-tag-Alexa Flour 488 (clone 4A6; EMD Millipore) and 2.7 µg/mL streptavidin R-phycoerythrin conjugate (Invitrogen) in staining buffer for 30 min at 4 °C. drTLR5N14 binders were isolated using a BD FACS Aria II sorter by gating on yeast cells double positive for drTLR5N14 and VLRB. The FACS-sorted yeast cells were plated on SD-CAA agar plates and individual colonies were picked and analyzed for TLR5 binding using a BD Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer and the FACS staining protocol described above. VLRB genes encoding for drTLR5N14 binders were PCR amplified from individual colonies after treatment with Zymolase (Zymogen) to digest the cell wall. The PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR clean up kit (Qiagen) and sequenced with pCT-ESO forward and reverse primers (ACGACGTTCCAGACTACG and TACAGTGGGAACAAAGTCG, respectively).

Recombinant protein expression and purification

VLR purification

Monomeric VLR expression constructs comprised of an N-terminal gp67 signal sequence, His6-tag and TEV cleavage site followed by VLR (VLR-1,-2,-9 constructs contained residues 21–188, 21–213, 21–182, respectively) were synthesized (Invitrogen) and cloned into pFastBac using SpeI/HindIII restriction sites. Plasmids were transformed into DH10Bac cells, bacmids were purified using PureLink kit (Invitrogen) and transfected into Sf9 cells using FuGene. Virus was amplified twice and used to infect Hi5 cells at a density of 1×106 cells/mL. Cultures were harvested after 3 days of shaking at 28 °C. Supernatant was concentrated and buffer exchanged into 25 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole and purified by His-tag affinity purification using NiNTA resin followed by gel filtration using a Superdex-75 column (GE LifeSciences). The VLRs eluted as monomers and were concentrated to 2.5 – 10.5 mg/mL for further use.

drTLR5N14 purification

A designed drTLR5N14 construct, containing zebrafish TLR5 LRRs 1 to 14 fused to a VLR-LLRCT34, was cloned into a modified pFastBac vector containing an N-terminal gp67 signal peptide, a C-terminal thrombin cleavage site, strepII-tag, and His6-tag. drTLR5N14 protein was expressed in Hi5 insect cells for three days at 28 °C. The supernatant was harvested and purified through a His-tag affinity purification step following by gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex-200 column (GE LifeSciences) and then cleaved overnight by thrombin to remove the His6StrepII tags. Cleaved drTLR5N14 was further purified by another His-tag affinity purification step followed by gel filtration chromatography using 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 buffer to remove the thrombin and uncleaved protein. The drTLR5N14 protein eluted as a monomer, was concentrated to 2.5 mg/ml and stored at −80 °C. The drTLR5-His6StrepII tagged protein used in pull-down assays was expressed and purified similarly, but without thrombin cleavage.

Flagellin purification

Flagellin from Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhimurium (amino acid residues 1–495) was cloned into pET-49b with an N-terminal His6-tag and thrombin cleavage site. Flagellin was expressed in T7 Express E. coli cells (New England Biolabs) for 2 hours at 37 °C from LB cultures grown to O.D. 0.4–06 and induced with 0.4 mM IPTG. Cells were lysed by performing three passages through an EmulsiFlix-C3 cell disrupter (Avestin). Lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 30000g for 30 min. Flagellin was purified from the clarified lysate using NiNTA resin and then the His6-tag was cleaved overnight by thrombin. Cleaved flagellin was further purified by an NiNTA flow through step, followed by a HiTrap Benzamadine FF column (GE LifeSciences) to remove thrombin, and gel filtration on Superdex-200 (GE LifeSciences). Endotoxin-free flagellin was prepared using Pierce high-capacity endotoxin removal spin columns. Endotoxin-free flagellin was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Kinetic measurements of TLR5/VLR binding

Binding affinities for VLRs to drTLR5N14 were quantitated using biolayer interferometry on an OctetRED instrument (ForteBio). Proteins were diluted in kinetics buffer (1% BSA, 0.2% Tween20, PBS). For each VLR, NiNTA sensors were loaded with His6-VLR (25 ng/µL) and then incubated with dilution series of drTLR5N14 (association phase, TLR5 concentration range 3 – 200 nM), and then buffer (dissociation phase). Curve fitting was done using OctetRED analysis software.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Binding experiments were performed by isothermal titration calorimetry using an Auto-ITC instrument (GE Healthcare). Before conducting the titrations VLR and TLR5 were extensively dialyzed overnight against 25 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl buffer. Concentrations were determined by measuring A280 and calculated extinction coefficients48. TLR5 was in the cell at 7–20 µM, VLR was in the syringe at 70–200 µM. The experiments consisted of 16 injections of 2.5 µL each, with injection duration of 5 s, injection interval of 180 s and reference power of 5 µcal. Origin 7.0 software was used to derive binding affinity constant (Kd), molar enthalpy (ΔH) and stoichiometry (N) using a single-site binding model.

Crystallization, structure determination and refinement

Apo-VLR2

VLR2 was crystallized in sitting drops containing 100 nL of protein (5.3 mg/mL) and 100 nL of reservoir (0.2 M (NH4)2SO4, 30% PEG 8K) at 20 °C. VLR2 crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen with 10% ethylene glycol as a cryo-protectant. Diffraction data for VLR2 were collected on SSRL beamline 12-2 and processed using HKL2000. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using Phaser49 and N-terminal and C-terminal regions of apo-VLR9 as search models.

Apo-VLR9

VLR9 was crystallized in sitting drops containing 100 nL of protein (10.5 mg/mL) and 100 nL of reservoir (2.0 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M citrate pH 5.5) at 20 °C. VLR9 crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen with 15% ethylene glycol as cryo-protectant. Diffraction data for VLR9 were collected on SSRL beamline 9-2 and processed using HKL2000. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using Phaser49 and VLR from the VLR/BclA co-crystal structure (PDB code 3TWI13, 84% sequence identity with VLR9).

VLR2/drTLR5

Purified VLR2 and TLR5 were mixed in equimolar amounts and co-concentrated to 16 mg/mL in 25 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl. The VLR2-TLR5 complex was crystallized in sitting drops containing 150 nL of protein and 150 nL of reservoir (16% PEG 8K, 180 mM ammonium citrate, 90 mM MES pH 6.0, 10 mM urea) at 20 °C. Crystals were harvested, cryoprotected with 15% ethylene glycol, and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at APS beamline 23ID-D and processed using HKL2000 in P21212 space group. Molecular replacement using Phaser in Phenix49 with search models for TLR5 monomer (PDB code 3V4732) and the apo-VLR2 structure identified two copies of a TLR5-VLR complex in the asymmetric unit.

VLR9/drTLR5

Purified VLR9 and TLR5 were mixed in equimolar amounts and co-concentrated to 12 mg/mL in 25 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl. The VLR9-TLR5 complex was crystallized in sitting drops containing 150 nL of protein and 150 nL of reservoir (15% PEG3350, 170 mM MgNO3, 80 mM MES pH 6.0, 15% ethylene glycol) at 20 °C. Crystals were harvested and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at APS beamline 23ID-D. Data were indexed and processed using HKL2000 in P21212 space group. Molecular replacement using Phaser49 with search models for TLR5 monomer (PDB code 3V4732) and the apo-VLR9 structure identified two copies of a TLR5-VLR9 complex in the asymmetric unit.

Structure refinement and analysis

Molecular replacement solutions were refined using rigid body and iterative cycles of restrained refinement in Phenix Refine49, 50 and manual fitting in Coot51. Data collection and refinement statistics for all three structures are shown in Table 2. Binding surface area calculations were performed using MS52. Graphics were prepared in PyMOL53.

Cell-based assays

HEK-hTLR5 reporter cell assays

Endotoxin-free recombinant protein combinations (flagellin, drTLR5, VLR) or PBS (negative control) in a total volume of 20 µL were aliquoted into a 96-well assay plate. HEK-Blue-hTLR5 cells (InvivoGen, CA) diluted in HEK-Blue detection media were added at a density of 25,000 cells per well (180 µL per well). Assay plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 12 – 16 hours prior to SEAP quantitation. SEAP was quantitated using a microplate reader to measure absorbance at 620 nm. Absorbance data were corrected by subtracting background (A620nm(sample) - A620nm[HEKhTLR5 + PBS]) and then normalized by dividing by the corrected absorbance of HEK-hTLR5 stimulated with 2 ng total flagellin (100% activity). Stimulation of HEK-hTLR5 cells by 2 ng flagellin was effectively inhibited by the inclusion of exogenous drTLR5N14 (200 ng). All assays were performed in triplicate with low passage cells (< 20 passages). For general maintenance, HEK-hTLR5 cells were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 in complete growth media containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and antibiotics (50 U/mL penicillin, 50 µg/mL streptomycin, 100 µg/mL Normocin, 10 µg/mL Blasticidin, 100 µg/mL Zeocin).

Immunoprecipitation assay

VLR (His6-tag) and drTLR5N14 (His6StrepII-tag) were incubated with HEK-hTLR5 cells as described for SEAP signal assays. Supernatants were collected by centrifugation and applied to strep-tactin coated magnetic beads (IBA life sciences, Germany). Samples were incubated on ice for 1 hour to allow drTLR5N14-His6StrepII to bind the beads. Beads were washed three times (100 mM Tris pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) to remove any unbound protein. Protein was eluted from beads by boiling in SDS page reducing sample buffer. Western blot analysis was performed using 1:5000 dilution of Anti-HIS-HRP conjugated antibody (Qiagen) to detect His6 tags on VLR and drTLR5. Negative controls without drTLR5N14 were performed in parallel to confirm that VLR did not directly bind to the magnetic beads.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

VLR antibodies in jawless fish use an LRR framework for antigen recognition

Three VLRs with high affinity for TLR5 were identified from immunized lamprey

VLRs block TLR5 binding to flagellin in cell-based assays

Crystal structures revealed two different epitopes on TLR5

Molecular recognition of protein antigens by non-Ig antibodies

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Henry Tien for automated crystal screening, Steffen Bernard for critical reading of the manuscript, Xiaoping Dai for data processing support, and Thomas Hrabe for ConSole analysis. This work is supported by NIH grants R01 AI042266 (I.A.W.) and R01 AI072435 (M.D.C.). X-ray data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) beamline 23-ID and Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL). Use of the APS was supported by the DOE, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the SSRL, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract no. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the NIH, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393 and P41GM103694) and the National Cancer Institute (U01CA199882). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH. This is publication number 29632 from The Scripps Research Institute.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- VLR

Variable lymphocyte receptor

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- LRR

leucine-rich repeat

- LRRNT

N-terminal LRR cap

- LRRV

variable LRR

- LRRVe

LRRV-end

- CP

connecting peptide

- LRRCT

C-terminal LRR cap

- CT-loop

variable insert

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- BclA

Bacillus collagen-like protein of anthracis spores

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- ECD

extracellular domain

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- YSD

yeast surface display

- dr

Danio rerio

- MACS

magnetic-activated cell sorting

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- EDC/NHS

(1-ethyl-3-(–3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride / N-hydroxysuccinimide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession numbers

Crystal structures reported here have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) under PDB ID codes 6BXD (VLR2), 6BXE (VLR9), 6BXA (drTLR5N14/VLR2) and 6BXC (drTLR5N14/VLR9).

References

- 1.Alder MN, Rogozin IB, Iyer LM, Glazko GV, Cooper MD, Pancer Z. Diversity and function of adaptive immune receptors in a jawless vertebrate. Science. 2005;310:1970–1973. doi: 10.1126/science.1119420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pancer Z, Amemiya CT, Ehrhardt GR, Ceitlin J, Gartland GL, Cooper MD. Somatic diversification of variable lymphocyte receptors in the agnathan sea lamprey. Nature. 2004;430:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature02740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrin BR, Alder MN, Roux KH, Sina C, Ehrhardt GR, Boydston JA, Turnbough CL, Jr, Cooper MD. Structure and specificity of lamprey monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2040–2045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711619105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrin BR, Cooper MD. Alternative adaptive immunity in jawless vertebrates. J. Immunol. 2010;185:1367–1374. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pancer Z, Saha NR, Kasamatsu J, Suzuki T, Amemiya CT, Kasahara M, Cooper MD. Variable lymphocyte receptors in hagfish. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9224–9229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503792102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo P, Hirano M, Herrin BR, Li J, Yu C, Sadlonova A, Cooper MD. Dual nature of the adaptive immune system in lampreys. Nature. 2009;459:796–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirano M, Guo P, McCurley N, Schorpp M, Das S, Boehm T, Cooper MD. Evolutionary implications of a third lymphocyte lineage in lampreys. Nature. 2013;501:435–438. doi: 10.1038/nature12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasamatsu J, Sutoh Y, Fugo K, Otsuka N, Iwabuchi K, Kasahara M. Identification of a third variable lymphocyte receptor in the lamprey. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14304–14308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001910107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das S, Li J, Hirano M, Sutoh Y, Herrin BR, Cooper MD. Evolution of two prototypic T cell lineages. Cell. Immunol. 2015;296:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alder MN, Herrin BR, Sadlonova A, Stockard CR, Grizzle WE, Gartland LA, Gartland GL, Boydston JA, Turnbough CL, Jr, Cooper MD. Antibody responses of variable lymphocyte receptors in the lamprey. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:319–327. doi: 10.1038/ni1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins BC, Gunn RJ, McKitrick TR, Cummings RD, Cooper MD, Herrin BR, Wilson IA. Structural insights into VLR fine specificity for blood group carbohydrates. Structure. 2017;25:1667–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han BW, Herrin BR, Cooper MD, Wilson IA. Antigen recognition by variable lymphocyte receptors. Science. 2008;321:1834–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.1162484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirchdoerfer RN, Herrin BR, Han BW, Turnbough CL, Jr, Cooper MD, Wilson IA. Variable lymphocyte receptor recognition of the immunodominant glycoprotein of Bacillus anthracis spores. Structure. 2012;20:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velikovsky CA, Deng L, Tasumi S, Iyer LM, Kerzic MC, Aravind L, Pancer Z, Mariuzza RA. Structure of a lamprey variable lymphocyte receptor in complex with a protein antigen. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:725–730. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogozin IB, Iyer LM, Liang L, Glazko GV, Liston VG, Pavlov YI, Aravind L, Pancer Z. Evolution and diversification of lamprey antigen receptors: evidence for involvement of an AID-APOBEC family cytosine deaminase. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:647–656. doi: 10.1038/ni1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo M, Velikovsky CA, Yang X, Siddiqui MA, Hong X, Barchi JJ, Jr, Gildersleeve JC, Pancer Z, Mariuzza RA. Recognition of the Thomsen-Friedenreich pancarcinoma carbohydrate antigen by a lamprey variable lymphocyte receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:23597–23606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.480467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boehm T, McCurley N, Sutoh Y, Schorpp M, Kasahara M, Cooper MD. VLR-based adaptive immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:203–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng L, Velikovsky CA, Xu G, Iyer LM, Tasumi S, Kerzic MC, Flajnik MF, Aravind L, Pancer Z, Mariuzza RA. A structural basis for antigen recognition by the T cell-like lymphocytes of sea lamprey. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:13408–13413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005475107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tasumi S, Velikovsky CA, Xu G, Gai SA, Wittrup KD, Flajnik MF, Mariuzza RA, Pancer Z. High-affinity lamprey VLRA and VLRB monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12891–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904443106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binz HK, Pluckthun A. Engineered proteins as specific binding reagents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005;16:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moot R, Raikar SS, Fleischer L, Querrey M, Tylawsky DE, Nakahara H, Doering CB, Spencer HT. Genetic engineering of chimeric antigen receptors using lamprey derived variable lymphocyte receptors. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2016;3:16026. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janeway CA, Jr, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik MJ. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5. New York: Garland Science; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamers-Casterman C, Atarhouch T, Muyldermans S, Robinson G, Hamers C, Songa EB, Bendahman N, Hamers R. Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature. 1993;363:446–448. doi: 10.1038/363446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenberg AS, Avila D, Hughes M, Hughes A, McKinney EC, Flajnik MF. A new antigen receptor gene family that undergoes rearrangement and extensive somatic diversification in sharks. Nature. 1995;374:168–173. doi: 10.1038/374168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huston JS, Mudgett-Hunter M, Tai MS, McCartney J, Warren F, Haber E, Oppermann H. Protein engineering of single-chain Fv analogs and fusion proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1991;203:46–88. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)03005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binz HK, Amstutz P, Kohl A, Stumpp MT, Briand C, Forrer P, Grutter MG, Pluckthun A. High-affinity binders selected from designed ankyrin repeat protein libraries. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:575–582. doi: 10.1038/nbt962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Binz HK, Amstutz P, Pluckthun A. Engineering novel binding proteins from nonimmunoglobulin domains. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1257–1268. doi: 10.1038/nbt1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SC, Park K, Han J, Lee JJ, Kim HJ, Hong S, Heu W, Kim YJ, Ha JS, Lee SG, Cheong HK, Jeon YH, Kim D, Kim HS. Design of a binding scaffold based on variable lymphocyte receptors of jawless vertebrates by module engineering. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:3299–3304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113193109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velàsquez AC, Nomura K, Cooper MD, Herrin BR, He SY. Leucine-rich-repeat-containing variable lymphocyte receptors as modules to target plant-expressed proteins. Plant Methods. 2017;13:29. doi: 10.1186/s13007-017-0180-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int. Immunol. 2005;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, Hawn TR, Yi EC, Goodlett DR, Eng JK, Akira S, Underhill DM, Aderem A. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon SI, Kurnasov O, Natarajan V, Hong M, Gudkov AV, Osterman AL, Wilson IA. Structural basis of TLR5-flagellin recognition and signaling. Science. 2012;335:859–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1215584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song WS, Jeon YJ, Namgung B, Hong M, Yoon SI. A conserved TLR5 binding and activation hot spot on flagellin. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40878. doi: 10.1038/srep40878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong M, Yoon SI, Wilson IA. Recombinant expression of TLR5 proteins by ligand supplementation and a leucine-rich repeat hybrid technique. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;427:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SJ, Chen Z, Chamberlain ND, Essani AB, Volin MV, Amin MA, Volkov S, Gravallese EM, Arami S, Swedler W, Lane NE, Mehta A, Sweiss N, Shahrara S. Ligation of TLR5 promotes myeloid cell infiltration and differentiation into mature osteoclasts in rheumatoid arthritis and experimental arthritis. J. Immunol. 2014;193:3902–3913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chamberlain ND, Vila OM, Volin MV, Volkov S, Pope RM, Swedler W, Mandelin AM, 2nd, Shahrara S. TLR5, a novel and unidentified inflammatory mediator in rheumatoid arthritis that correlates with disease activity score and joint TNF-alpha levels. J. Immunol. 2012;189:475–483. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das N, Dewan V, Grace PM, Gunn RJ, Tamura R, Tzarum N, Watkins LR, Wilson IA, Yin H. HMGB1 activates proinflammatory signaling via TLR5 leading to allodynia. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1128–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kassem A, Henning P, Kindlund B, Lindholm C, Lerner UH. TLR5, a novel mediator of innate immunity-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone loss. FASEB J. 2015;29:4449–4460. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-272559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan L, Liang J, Yao C, Wu P, Zeng X, Cheng K, Yin H. Pyrimidine triazole thioether derivatives as toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5)/flagellin complex inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:822–826. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201500471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim SJ, Chen Z, Chamberlain ND, Volin MV, Swedler W, Volkov S, Sweiss N, Shahrara S. Angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis is fostered directly by toll-like receptor 5 ligation and indirectly through interleukin-17 induction. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2024–2036. doi: 10.1002/art.37992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashemi H, Hasanzadeh M, Amanlou M. Fragment pharmacophore-based screening: an efficient approach for discovery of new inhibitors of Toll-Like Receptor 5. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2016;19:834–840. doi: 10.2174/1386207319666160907103507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hrabe T, Godzik A. ConSole: using modularity of contact maps to locate solenoid domains in protein structures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong X, Ma MZ, Gildersleeve JC, Chowdhury S, Barchi JJ, Jr, Mariuzza RA, Murphy MB, Mao L, Pancer Z. Sugar-binding proteins from fish: selection of high affinity “lambodies” that recognize biomedically relevant glycans. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:152–160. doi: 10.1021/cb300399s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salazar Gonzalez RM, Shehata H, O’Connell MJ, Yang Y, Moreno-Fernandez ME, Chougnet CA, Aliberti J. Toxoplasma gondii- derived profilin triggers human toll-like receptor 5-dependent cytokine production. J. Innate Immun. 2014;6:685–694. doi: 10.1159/000362367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burdelya LG, Krivokrysenko VI, Tallant TC, Strom E, Gleiberman AS, Gupta D, Kurnasov OV, Fort FL, Osterman AL, Didonato JA, Feinstein E, Gudkov AV. An agonist of toll-like receptor 5 has radioprotective activity in mouse and primate models. Science. 2008;320:226–230. doi: 10.1126/science.1154986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi T, Li L, Zhou G, Wang C, Chen X, Zhang R, Xu J, Lu X, Jiang H, Chen J. Tolllike receptor 5 agonist CBLB502 induces radioprotective effects in vitro. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2017;49:487–495. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmx034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burns ML, Malott TM, Metcalf KJ, Hackel BJ, Chan JR, Shusta EV. Directed evolution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor for improved folding and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:5732–5742. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01466-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In: Walker JM, editor. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, Adams PD. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Connolly ML. The molecular surface package. J. Mol. Graph. 1993;11:139–141. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(93)87010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schrodinger LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 2015 Version 1.8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.