Abstract

Objective

To evaluate a multilevel cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention program for rural women.

Methods

This six-month community-based randomized trial enrolled 194 sedentary rural women aged 40 or older, with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. Intervention participants attended six months of twice-weekly exercise, nutrition, and heart health classes (48 total) that included individual-, social-, and environment-level components. An education-only control program included didactic healthy lifestyle classes once a month (6 total). The primary outcome measures were change in BMI and weight.

Results

Within group and between group multivariate analyses revealed that only intervention participants decreased BMI (−0.85 units; 95% CI 1.32, −0.39; p=0.001) and weight (−2.24 kg; −3.49, −0.99; p=0.002); compared to controls, intervention participants decreased BMI and weight (difference: −0.71 units; −1.35, −0.08; p=0.03 and 1.85 kg; −3.55, −0.16; p=0.03, respectively) and improved C-reactive protein (difference: −1.15; −2.16, −0.15; p=0.03) and Simple 7, a composite CVD risk score (difference=0.67; 0.14, 1.21; p=0.01). Cholesterol decreased in controls but increased among intervention (−7.85 versus 3.92; difference=11.77; 0.57, 22.96; p=0.04).

Conclusions

The multilevel intervention demonstrated modest but superior and meaningful improvements in BMI and other CVD risk factors compared to the control program.

Keywords: Cardiovascular, rural, women, heart health, physical activity

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality in the United States, accounting for approximately one-quarter of all deaths (1). People living in rural areas are more likely to be diagnosed with CVD and exhibit more CVD risk factors than those in urban areas including smoking, having type 2 diabetes, having a BMI in the overweight or obese categories, and having a sedentary lifestyle (2, 3). Rural women are also more likely to be uninsured, older, lower income, less educated, and have higher rates of chronic health conditions – due, in part, to limited access to physical activity opportunities, healthy foods, and healthcare resources (4–7). Thus, women living in rural, medically underserved areas are a critical target population for CVD prevention efforts.

Didactic education-only, individual-level approaches are common among weight management and healthy lifestyle programs, despite the fact that experiential, hands-on learning techniques tend to result in superior outcomes (8). While the socioecological model is often referenced in the context of health behavior change interventions and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics notes “interventions incorporating more than one level of the socioecological model and addressing several key factors in each level may be more successful than interventions targeting any one level and factor alone,” (9) few programs have actively engaged the individual, social, and environmental spheres of influence to help support behavior change. In addition, a recent review found that evidence-based interventions promoting physical activity and healthy eating for adults are limited by lack of high-quality, multilevel intervention studies (10). This is likely due to lack of clear, specific strategies for linking multiple socioecological levels (11).

The objective of Strong Hearts, Healthy Communities (SHHC) was to address these gaps by: 1) developing an innovative intervention informed by the socioecological framework to target key behaviors related to CVD prevention and overweight/obesity, bolstering social and environmental support through civic engagement, 2) integrating an experiential learning approach including core concepts of experience; observation and reflection; analysis and generalizations; and application to future situations, 3) conducting a pragmatic comparative effectiveness trial evaluating SHHC compared to an education-only, minimal intervention control program, Strong Hearts, Healthy Women (CON) on anthropometric and physiologic outcomes. We hypothesized that there would be superior improvement in the full intervention program, resulting in significant and clinically meaningful improvements in CVD risk factors.

METHODS

Design

This community randomized intervention trial occurred during 2015–2016 in 16 towns in Montana and New York. All towns were rural (based on Rural Urban Commuting Area designations) (12) and were designated as medically underserved areas or populations (13). Population per town ranged from 470 to 5,900, with an average of 2,200 residents. Randomization occurred at the town level, with half randomized to deliver the SHHC intervention program and half to deliver the CON program. The study protocol has been previously published (14). The study was approved by the Cornell University and Bassett Healthcare Institutional Review Boards.

Participants

Participants were recruited by local health educators through word of mouth, community advertising (e.g., posters/flyers at senior centers), recruitment events (e.g., tables at grocery stores), newspaper ads and articles, radio ads, Facebook, website posts, and targeted direct mailing. Eligible participants were female, 40 years or older, with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, sedentary (not meeting the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans or having an estimated total energy expenditure below 34 kcal/kg per day, per the 7-day Physical Activity Recall), English-speaking, and had their physician’s approval to participate. Participants with blood pressure >100 (diastolic) or >160 (systolic), heart rates of <60 or >100, or cognitive impairments were excluded. All participants provided written informed consent.

Program Educators

The fourteen program educators who delivered the program were members of each local community, affiliated with cooperative Extension offices or a local rural healthcare system, and had experience delivering health education programs to adults. They also had CPR certification, training in human subjects’ ethics, and extensive training in research methods related to the study and the curriculum to be delivered; trainings were conducted through in-person workshops, webinars, and weekly phone calls. Full details are described in the protocol manuscript (14).

The Multilevel Intervention Program and Minimal Intervention Control Program

The multilevel SHHC intervention program integrated three evidence-based community programs—two targeting the individual and a third targeting positive change in social and built environments (15–17). SHHC focused on behavior change through experiential learning in the following areas: dietary improvement, physical activity and fitness, weight loss, and other relevant CVD-related prevention skills and strategies such as stress management. Grocery store audits and community food and physical activity environment assessments (e.g., local walking tour to identify barriers and facilitators to active living and healthy eating) included friends and family members, as part of the social environment and HEART Club civic engagement component. SHHC participants met twice weekly for 24 weeks (48 one-hour classes).

The diet component aimed to change dietary patterns through classroom skill-building activities (e.g., measuring true portion sizes, label reading) and field-based learning (e.g., grocery store audits, home food environment awareness activities); it was informed by DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet principles (18), the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (19), and the Mediterranean dietary pattern (20). Nutrition behavioral aims included increasing fruits and vegetables, replacing refined grains with whole grains, and decreasing calories, desserts, processed foods, saturated and trans fats, sodium, and sugar-sweetened beverages.

SHHC physical activities included aerobic exercise (e.g., indoor and outdoor walking; aerobic dance)—starting low to moderate with a transition to moderate to vigorous intensity; progressive strength training exercises for upper and lower body and core; and field-based learning with reflections (e.g., community walking tour). Goal setting, behavioral feedback and tracking, and motivational interviewing techniques were used. Progressive, moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (typically 20–30 minutes), such as walking DVDs and aerobic dance, was included in nearly all classes. Progressive strength training (typically 10–20 minutes; two sets of ten repetitions) of major muscle groups, such as squats, lunges, bicep curls, and chest press, was included in about two-thirds of classes. Participants were encouraged to increase the intensity of both exercise components throughout the program.

Curriculum content addressed the social environment’s influence on heart-healthy behavior related to diet and exercise; social support for heart-healthy behaviors; heart-healthy eating plans for friends and family; social influences on sugar-sweetened beverage consumption; and what to do when loved ones are unsupportive. Engagement and reinforcement of these concepts occurred within HEART Club activities, which also formalized knowledge/awareness of built environment change opportunities to support healthy lifestyles in rural towns, a novel feature of the intervention program. The HEART Club used a formal, step-wise process with groups identifying a food or physical activity environment issue they believed important and feasible to address in their community to support healthier lifestyles, followed by a system to articulate and evaluate action steps by the group (15). To facilitate HEART Club efforts and raise general awareness of local resources for healthy eating and active living, there were HEART Club community activities, designed by participants, based upon the issue and action steps identified, with the goal of participants acting as positive change agents for their families, friends, and communities (21). As an additional component to support the multilevel approach of the intervention, Community Guides were developed for each SHHC community with lists of and basic information about local resources for healthy eating, physical activity, healthcare and wellness, and community change.

The Strong Hearts, Healthy Women control (CON) classes served as the reduced-dose, education-only minimal intervention control program. The CON classes met for a one-hour class once per month over 24 weeks (six classes total). Classes provided evidence-based healthy lifestyle information (e.g., current dietary and physical activity guidelines), presented didactically. Participants did not engage in physical activity, skill-building, or other active learning elements (e.g., reflection, monitoring) or civic engagement during the class sessions.

Outcome Assessments

Analysis for the current study includes baseline data and post-intervention (outcome) data, collected immediately following the six-month intervention. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire at baseline only, unless they indicated a change (e.g., marital status). Demographic questions were derived from national surveys (e.g., U.S. Census). Participants also completed behavioral and health-related questionnaires at baseline and post-intervention, including data on relevant diagnoses and medications (e.g. hyperlipidemia; statin use). Qualtrics was used for questionnaire-based data collection.

Anthropometric measures included height, weight, body mass index (BMI: weight [kg]/height [m2]), body composition, and hip and waist circumference; all measured in duplicate (only in triplicate if needed per study protocol). Freestanding Seca model 213 stadiometers were used for height measurements; Omron HBF-510W scales were used for weight and body composition measures. A retractable Gulick tape measure was used for hip and waist circumferences. Physiologic measures included blood pressure, resting heart rate, and fasting (overnight, ≥ 12 hours) blood draws to assess glucose, hemoglobin A1c, c-reactive protein (CRP), and lipid panel with total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. Anthropometric and physiologic measures were completed by independent, trained staff from Western Health Screening in Montana and Bassett Healthcare Network in New York.

Simple 7 is a cardiovascular health metric comprised of four health behaviors (smoking, body mass index, physical activity, healthy diet) and three health factors (total cholesterol, blood pressure, fasting glucose) (22). The classification scores determined by the American Heart Association (AHA) are poor, intermediate, or ideal, which are correlated with prevalence of CVD events (23). The Simple 7 components for this study were derived from a combination of self-reported (smoking, physical activity by IPAQ (24), healthy diet (25)) and measured (BMI, total cholesterol, blood pressure, fasting serum glucose) data. To calculate the Simple 7 score, the number of ideal/intermediate/poor Simple 7 components for each participant was counted. Ideal cardiovascular health is defined as having all seven cardiovascular health metrics in the ideal range. Intermediate cardiovascular health is defined as having at least one intermediate metric and no poor metrics. Poor cardiovascular health is defined as having at least one poor health metric. Further details are provided in Table S1 that describe each characterization for the poor, intermediate, and ideal score, as well as the data source for each measure included in the analysis for this study. In addition, ten-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) was calculated using the Pooled Cohort Equations (26).

Statistical Analysis

Sample size and randomization

Our sample size estimates were based upon the StrongWomen—Healthy Hearts study (16) in which intervention participants lost an average of 2.1 kilograms (SD=2.6) compared to controls. It was determined that a sample size of 34 people per group would allow us to detect an effect size of 0.690 from a 2-sided independent means test with 80% power and Type 1 error of 5%. Given the data were clustered within towns, we assumed intra-class correlation of 0.025 (with clusters of 12 people) and 10% initial attrition, resulting in a design effect of 1.275, yielding a sample size requirement of 48 people per group (96 total). To ensure adequate power, taking into consideration the potential for additional attrition and possible subgroup analyses based upon baseline characteristics, additional participants were recruited. For randomization, towns were paired based upon closest match to rural (RUCA 2.0) designation and population size (27). Following completion of participants’ baseline assessments, the statistician randomly assigned one town from each pair to receive the intervention (SHHC) or control (CON) program.

Univariate descriptive statistics for the entire sample and by treatment group were compiled and tabulated. Comparison between baseline characteristics was completed using chi-square test (binary and categorical variables) and t-test (continuous variables). Since observations were clustered within towns, multilevel linear regression models were used (Model 1), where site was treated as a random effect to examine adjusted effects of the intervention on the primary outcomes (change in BMI and body weight) and key secondary outcomes [physiologic (e.g. blood pressure, lipids, CRP, hemoglobin A1c), anthropometric (e.g. waist circumference) and aggregate (e.g. Simple 7, ASCVD risk)] following a modified intent to-treat analysis (28) where all participants who completed data collection were analyzed according to their randomized treatment assignment, regardless of their level of intervention adherence (complete case analysis). The a priori multivariate participant model (Model 2) controlled for baseline values of the outcome (29), age, marital status, and education, as fixed effects in addition to the treatment variable. Table 2 displays Model 1 and Model 2 as within group pre- to post-intervention change values and significance of those changes within each treatment group (SHHC and CON). Table 3 displays Model 1 and Model 2 as the between group comparison of the pre- to post-intervention change values and significance of those change differences between the two treatment groups. Multilevel ordinal logistic regression models were used to assess the effect of the intervention on Simple 7. All tests were 2-sided, and p≤0.05 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance. In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses in which missing data were imputed and the last observation was carried forward (LOCF), which are included in the supplemental tables (Tables S2 and S3). Sample sizes for the complete case analysis and LOCF are noted in Figure 1 and in each of the tables. Analyses were conducted using the PROC MIXED command for multilevel analysis in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC),.

Table 2.

Within Group Changes in BMI, Weight, and CVD Risk Factors

| Unadjusted Model 1b N range = 129–151 |

Multivariate Model 2c N range = 127–145 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within Group Change (SHHC Intervention) | Within Group Change (CON) | Within Group Change (SHHC Intervention) | Within Group Change (CON) | |||||

| Mean Change Baseline to Outcome (95% CI) | p- value | Mean Change Baseline to Outcome (95% CI) | p- value | Mean Change Baseline to Outcome (95% CI) | p-value | Mean Change Baseline to Outcome (95% CI) | p- value | |

| BMIa | −0.80 (−1.18, − 0.43) | <0.001 | −0.10 (−0.49, 0.29) | 0.60 | −0.85 (−1.32, − 0.39) | 0.001 | −0.14 (−0.62, 0.33) | 0.53 |

| Weight, kg | −2.09 (−3.10, −1.08) | <0.001 | −0.23 (−1.28, 0.83) | 0.65 | −2.24 (−3.49, − 0.99) | 0.002 | −0.38 (−1.65, 0.88) | 0.53 |

| CRP | −1.31 (−2.06, − 0.55) | <0.001 | −0.02 (−0.84, 0.80) | 0.96 | −1.13 (−1.89, − 0.37) | 0.004 | 0.03 (−0.75, 0.80) | 0.95 |

| Simple 7 | 0.93 (0.53, 1.33) | <0.001 | 0.32 (−0.11, 0.76) | 0.14 | 0.88 (0.48, 1.28) | <.0.001 | 0.21 (0.21, 0.63) | 0.32 |

| ASCVD Risk | −0.86 (−1.43, − 0.29) | 0.004 | −0.32 (−0.94, 0.29) | 0.30 | −0.96 (−1.49, − 0.43) | <0.001 | −0.47 (−1.01, 0.065) | 0.09 |

| Waist to hip ratio | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.36 | −0.003 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.64 | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.24 | −0.002 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.80 |

| Body fat, % | −1.56 (−2.01, − 1.10) | <0.001 | −1.71 (−2.21, − 1.20) | <0.001 | −1.65 (−2.20, − 1.11) | <0.001 | −1.87 (−2.44, − 1.30) | <0.001 |

| Resting heart rate | −2.76 (−4.60, − 0.92) | 0.004 | −1.17 (−3.18, 0.83) | 0.25 | −1.88 (−3.85, 0.08) | 0.06 | −1.15 (−3.16, 0.86) | 0.26 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | −6.46 (−9.60, − 3.32) | <0.001 | −4.53 (−7.73, − 1.32) | 0.009 | −6.45 (−9.63, − 3.28) | <0.001 | −3.89 (−7.09, − 0.68) | 0.02 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | −6.57 (−10.51, − 2.64) | 0.003 | −4.14 (−8.21, − 0.07) | 0.05 | −5.91 (−10.35, − 1.46) | 0.01 | −3.85 (−8.32, 0.63) | 0.09 |

| Waist circumference, cm | −3.39 (−6.10, − 0.68) | 0.02 | −2.10 (−4.84, 0.64) | 0.12 | −3.23 (−5.78, − 0.68) | 0.02 | −1.83 (−4.41, 0.75) | 0.15 |

| Cholesterol (total), mg/dL | 2.68 (−5.43, 10.79) | 0.49 | −9.41 (−17.72, − 1.10) | 0.03 | 3.92 (−4.22, 12.06) | 0.32 | −7.85 (−16.05, 0.35) | 0.06 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.93 (−1.75, 3.61) | 0.47 | 0.55 (−2.21, 3.32) | 0.68 | 1.81 (−0.88, 4.50) | 0.17 | 0.54 (−2.18, 3.26) | 0.68 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.08 (−5.47, 5.63) | 0.98 | −8.08 (−13.83, − 2.32) | 0.009 | 0.99 (−5.02, 7.01) | 0.73 | −6.55 (−12.60, − 0.51) | 0.04 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | −5.28 (−20.49, 9.94) | 0.46 | −9.45 (−25.14, 6.24) | 0.22 | −3.39 (−16.97, 10.18) | 0.60 | −6.79 (−20.46, 6.89) | 0.31 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 2.66 (−1.57, 6.89) | 0.22 | 5.61 (1.00, 10.22) | 0.02 | 3.42 (−1.08, 7.92) | 0.14 | 5.06 (0.46, 9.67) | 0.03 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | −0.28 (−0.40, − 0.16) | <0.001 | −0.28 (−0.41, − 0.16) | <0.001 | −0.26 (−0.38, − 0.14) | <0.001 | −0.28 (−0.40, − 0.16) | <0.001 |

Boldface indicates statistical significance (p≤0.05)

Abbreviations: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CON, Strong Hearts, Healthy Women-Control; CRP, c-reactive protein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; SHHC, Strong Hearts, Healthy Communities.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Adjusted for Site

Adjusted for Site, Education, Age, Marital Status, and Baseline Value of the Outcome

Table 3.

Between Group Differences for Changes in BMI, Weight, and CVD Risk Factors

| Unadjusted Model 1b N range = 129–151 |

Multivariate Model 2c N range = 127–145 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in Change between SHHC and CON | Difference in Change between SHHC and CON | |||

| Mean Change Baseline to Outcome (95% CI) | p- value | Mean Change Baseline to Outcome (95% CI) | p- value | |

| BMIa | −0.71 (−1.25, −0.17) | 0.01 | −0.71 (−1.35, −0.08) | 0.03 |

| Weight, kg | −1.86 (−3.32, −0.41) | 0.02 | −1.85 (−3.55, −0.16) | 0.03 |

| CRP | −1.29 (−2.40, −0.17) | 0.02 | −1.15 (−2.16, −0.15) | 0.03 |

| Simple 7 | 0.61 (0.02, 1.20) | 0.04 | 0.67 (0.14, 1.21) | 0.01 |

| ASCVD Risk | −0.54 (−1.38, 0.30) | 0.21 | −0.48 (−1.19, 0.22) | 0.18 |

| Waist to hip ratio | −0.003 (−0.02, 0.02) | 0.76 | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.49 |

| Body fat, % | 0.15 (−0.53, 0.83) | 0.67 | 0.22 (−0.50, 0.94) | 0.54 |

| Resting heart rate | −1.58 (−4.30, 1.13) | 0.25 | −0.73 (−3.33, 1.87) | 0.58 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | −1.94 (−6.43, 2.56) | 0.37 | −2.57 (−6.95, 1.82) | 0.23 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | −2.44 (−8.10, 3.23) | 0.37 | −2.06 (−8.14, 4.03) | 0.48 |

| Waist circumference, cm | −1.29 (−5.15, 2.57) | 0.49 | −1.40 (−4.96, 2.16) | 0.41 |

| Cholesterol (total), mg/dL | 12.09 (0.49, 23.70) | 0.04 | 11.77 (0.57, 22.96) | 0.04 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.37 (−3.48, 4.22) | 0.84 | 1.27 (−2.39, 4.94) | 0.47 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 8.16 (0.17, 16.15) | 0.05 | 7.55 (−0.62, 15.71) | 0.07 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 4.18 (−17.66, 26.01) | 0.69 | 3.39 (−15.03, 21.82) | 0.69 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | −2.95 (−9.21, 3.30) | 0.35 | −1.65 (−7.60, 4.31) | 0.59 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 0.001 (−0.17, 0.17) | 0.99 | 0.02 (−0.14, 0.19) | 0.78 |

Boldface indicates statistical significance (p≤0.05)

Abbreviations: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CON, Strong Hearts, Healthy Women-Control; CRP, c-reactive protein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; SHHC, Strong Hearts, Healthy Communities.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Adjusted for Site

Adjusted for Site, Education, Age, Marital Status, and Baseline Value of the Outcome

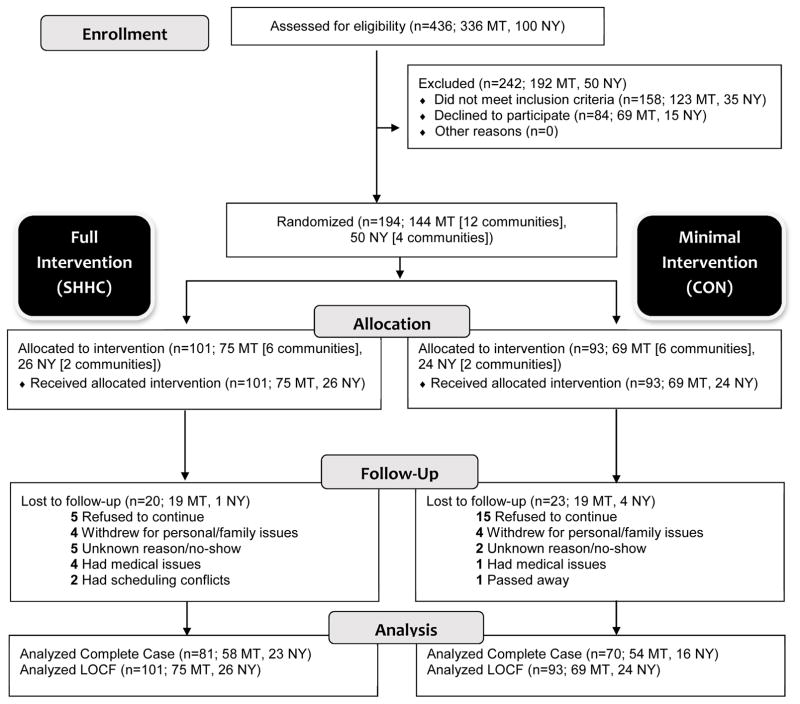

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart describing progress of participants through the study

Footnote: Abbreviations: CON, Strong Hearts, Healthy Women-Control; LOCF, Last Observation Carried Forward; MT, Montana; NY, New York; SHHC, Strong Hearts, Healthy Communities.

RESULTS

A total of 194 participants consented and were randomized; 151 (78%) completed both baseline and outcome assessments (Figure 1). There was a difference in two demographic characteristics between the intervention and control groups; intervention participants had a larger household size (mean [SD] household size 2.5 [1.4] people versus 2.1 [0.9] people) and greater number of children in the household (mean [SD] 1.4 [0.8] children versus 1.1 [0.5] children). There were no differences in baseline health measures between the intervention and control group participants (p≥0.05) (Table 1). Analysis revealed no differences in baseline characteristics among those for whom outcome data was or was not available, with the exception of an age interaction with Simple 7: the average age with a Simple 7 score was 59.8 years, while those for whom Simple 7 score was not available due to loss to follow-up or missing data, was 56.9 years, (p=0.04).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Intervention Condition

| Characteristic | Total (N range = 174–194) | SHHC (N range = 88–101) | CON (N range = 86–93) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58.9 (9.5) | 59.0 (9.4) | 58.7 (9.7) | |

| Income, No. (%) | ||||

| <$25,000 | 37 (21) | 24 (27) | 13 (15) | |

| $25,000–$50,000 | 53 (31) | 23 (26) | 30 (35) | |

| >$50,000 | 84 (48) | 41 (47) | 43 (50) | |

| Marital status, No. (%) | ||||

| In a relationship | Married | 130 (70) | 68 (72) | 62 (69) |

| Member of an unmarried couple | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Not in a relationship | Divorced | 20 (11) | 9 (9) | 11 (12) |

| Widowed | 22 (12) | 14 (15) | 8 (9) | |

| Separated | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| Never been married | 8 (4) | 1 (1) | 7 (8) | |

| Educational level, No. (%) | ||||

| High school or less | 42 (23) | 22 (23) | 20 (22) | |

| Technical or vocational school/some college | 55 (30) | 30 (32) | 25 (28) | |

| College graduate | 58 (32) | 28 (30) | 30 (33) | |

| Postgrad/professional | 29 (16) | 14 (15) | 15 (17) | |

| Household size (total), mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.1 (0.9) | |

| Number of adults in the household, mean (SD) | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.7) | |

| Number of children in the household, mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.5) | |

| Racial/ethnic minority, No. (%) | 10 (5) | 5 (5) | 5 (6) | |

| Employment status, No. (%) | ||||

| Employed for wages | 110 (59) | 50 (52) | 60 (67) | |

| Self-employed | 20 (11) | 11 (11) | 9 (10) | |

| Out of work for more than one year | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Out of work for less than one year | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| A homemaker | 9 (5) | 6 (6) | 3 (3) | |

| A student | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Retired | 41 (22) | 24 (25) | 17 (19) | |

| Unable to work | 5 (3) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| Smoking | 9 (5) | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | |

| BMI, mean (SD)a | 35.2 (6.5) | 34.9 (6.1) | 35.5 (6.8) | |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 93.8 (18.1) | 92.2 (16.8) | 95.5 (19.5) | |

| CRP, mean (SD) | 4.9 (4.3) | 4.8 (4.6) | 5.0 (3.9) | |

| Simple 7, mean (SD) | 7.3 (1.9) | 7.3 (1.9) | 7.2 (1.9) | |

| ASCVD Risk, mean (SD) | 7.2 (9.3) | 8.0 (10.7) | 6.3 (7.3) | |

| Waist to hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | |

| Body fat, mean (SD), % | 48.4 (5.0) | 48.2 (5.2) | 48.7 (4.9) | |

| Resting heart rate, mean (SD) | 73.1 (9.2) | 72.9 (8.8) | 73.3 (9.7) | |

| Diastolic blood pressure-Automated, mean (SD), mmHg | 87.5 (20.4) | 87.9 (27.1) | 87.1 (8.3) | |

| Systolic blood pressure-Automated, mean (SD), mmHg | 134.4 (17.1) | 134.7 (19.0) | 134.0 (14.9) | |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD), cm | 105.8 (12.7) | 104.9 (13.3) | 106.7 (12.0) | |

| Cholesterol (total), mean (SD), mg/dL | 203.7 (41.3) | 202.0 (44.2) | 205.5 (38.0) | |

| HDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 56.5 (14.5) | 57.6 (15.3) | 55.3 (13.5) | |

| LDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 124.8 (35.5) | 122.2 (37.4) | 127.7 (33.3) | |

| Triglycerides, mean (SD), mg/dL | 144.2 (72.7) | 145.9 (78.1) | 142.3 (66.7) | |

| Fasting glucose, mean (SD), mg/dL | 98.7 (22.0) | 98.4 (19.7) | 99.0 (24.3) | |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean (SD) | 6.1 (0.8) | 6.1 (0.8) | 6.1 (0.9) | |

Boldface indicates statistical significance (p≤0.05)

Abbreviations: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index; CON, Strong Hearts, Healthy Women-Control; CRP, c-reactive protein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; SHHC, Strong Hearts, Healthy Communities-Intervention.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Primary Outcomes (Body Weight and BMI)

In the pre-post within group multivariate analysis, only intervention participants significantly decreased BMI (−0.85 units, 95% CI −1.32 to −0.39; p=0.001) and weight (−2.24 kg, 95% CI −3.49 to −0.99; p=0.002); there were no improvements among controls (Table 2, Model 2). In the between group multivariate analysis, the intervention group lost significantly more weight (difference: −1.85 kg, 95% CI −3.55 to −0.16; p=0.03) compared to the control group (Table 3, Model 2). This equated to a significant BMI decrease among intervention participants, compared to controls (−0.71 units, 95% CI −1.35 to −0.08; p=0.03).

Secondary Outcomes

In the pre-post within group multivariate analysis, only intervention participants significantly decreased CRP (−1.13, 95% CI −1.89 to −0.37; p=0.004), Simple 7 (0.88, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.28; p<0.001), ASCVD risk (−0.96, 95% CI −1.49 to −0.43, p<0.001), systolic blood pressure (−5.91, 95% CI −10.35 to −1.46; p=0.01), and waist circumference (−3.23 cm, 95% CI −5.78 to −0.68; p=0.02); only the control group decreased LDL cholesterol (−6.55, 95% CI −12.60 to −0.51; p=0.04) and increased fasting glucose (5.06, 95% CI 0.46 to 9.67; p=0.03) (Table 2, Model 2). Both groups decreased body fat (intervention: −1.65, 95% CI −2.20 to −1.11; p<0.001; control: −1.87, 95% CI −2.44 to −1.30; p<0.001); diastolic blood pressure (intervention: −6.45, 95% CI −9.63 to −3.28; p<0.001; control: −3.89, 95% CI −7.09 to −0.68; p=0.02); and hemoglobin A1c (intervention: −0.26, 95% CI −0.38 to −0.14; p<0.001 control: −0.28, 95% CI −0.40 to −0.16; p<0.001) (Table 2, Model 2).

In the between group multivariate analysis, intervention participants significantly improved CRP and Simple 7 compared to controls (difference: −1.15, 95% CI −2.16 to −0.15; p=0.03 and 0.67, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.21; p=0.01, respectively) (Table 3, Model 2). In addition, the odds of an improvement in Simple 7 were more than twice as likely in the intervention group compared to the control group (odds ratio 2.45, p=0.004) (not shown in table). Total cholesterol levels improved among controls compared to intervention (difference: 11.77, 95% CI 0.57 to 22.96; p=0.04) (Table 3, Model 2). Primary and secondary outcome results were similar between the site-only adjusted (Model 1) and multivariate models (Model 2) as well as the last observation carried forward models (Tables S2 and S3).

Class Sessions and Civic Engagement

The average class size was 12 participants. Median class attendance was 77% in the intervention group and 83% in the control group; mean attendance was 74% and 68%, respectively. Analyses showed that among participants who attended at least 75% of their classes, intervention participants lost 1.01 more BMI units than controls (95% CI −1.83 to −0.194; p=0.04). Among participants attending less than 75% of classes, there was no difference in BMI change by group. For the HEART club civic engagement, groups engaged in community change projects and activities that included creating and/or improving walking trails and park areas; organizing and implementing countywide health fairs; and helping local restaurants identify healthy food choices on their menus for customers.

DISCUSSION

Rural women who participated in the multilevel, experiential, socioecological SHHC curriculum achieved greater weight loss and enhanced improvements in CVD risk factors, compared to the control program. The control group also benefitted in several parameters, although to a lesser degree; compared to intervention, they improved in terms of total cholesterol, but these changes lack explanation based upon the data collected, such as changes in medication use.

Our findings are similar to other community-based lifestyle interventions targeting CVD risk reduction among underserved (e.g., rural, low-income) populations (30–33). For example, Devine and colleagues, using an experiential education approach aimed at fruit and vegetable intake in low-income women, found significant increases in intake in intervention versus control group participants (32). The South Asian Heart Lifestyle Intervention also used both community-engaged and experiential learning approaches; intervention participants had significant weight loss and improved hemoglobin A1c levels compared to controls at six months (33).

In the current study, the odds of improvement in Simple 7 were more than twice as likely in the intervention group compared to the control group. In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, with a mean follow-up of nearly 19 years, participants with an ideal Simple 7 score had no CVD events, while CVD incidence was 7.5 per 1,000 person-years for those with intermediate Simple 7 scores and 14.6 for those with a poor Simple 7 score (23).

Compared to other interventions of a similar length, weight loss was modest. However, the goal of SHHC was step-wise, progressive (e.g., increased duration and intensity of aerobic exercise) lifestyle improvements to improve body weight and other CVD risk factors. Results of the SHHC study were similar to comparable healthy lifestyle interventions. For example, at the midpoint of Arredondo and colleagues’ two-year physical activity intervention, the intervention group decreased their BMI significantly more than the comparison group (−0.43 units, p=0.04), which is similar to our six-month study (−0.71 units, p=0.03) (34). Furthermore, the focus on social and built environment knowledge and activities, such as the HEART Club, do direct time away from individually-focused in-class activities such as exercise. Revisions are being made to the intervention curriculum to supplement the program’s classes with additional out-of-class support materials, tools, and “assignments” to keep individual-level progress on track.

Relevant to this study are minimal versus enhanced intervention studies and pragmatic comparative effectiveness studies. Some report no difference in BMI, blood pressure, or cholesterol between minimal interventions and enhanced interventions (35–37). However, similar to our findings, minimal interventions themselves may be robust enough to create change; other six-month behavior change interventions observed decreased weight and blood pressure with monthly classes (38, 39). Monthly contacts following a six-month intervention can yield superior weight maintenance compared to those not receiving contact (self-directed) (40). Additionally, a recent systematic review of multicomponent behavioral weight management programs suggested researchers assume minimal intervention control participants will lose up to a kilogram by the end of the first year follow-up (41).

Beyond the HEART Club civic engagement, additional activities were directed at the social and built environment of participants. For example, the walking tour allowed participants to document environmental opportunities and barriers to healthy eating and physical activity in their community. Although independent effects of civic engagement and the social and built environment components cannot be independently assessed with this design, they likely contributed additional benefits. For example, civic engagement can increase social, physical, and cognitive activity among older adults (42). Volunteering has been linked to lower hypertension risk and a higher probability of achieving physical activity recommendations in older adults (42).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognizes the impacts of built and social environments and recommends changing them to promote healthier living (43). Particularly important is the built environment, including food stores, sidewalks, streets, parks, and bike lanes. Growing evidence links built environment features to obesity and related health behaviors, including physical activity and eating patterns (44). Changes in the built environment have shown potential in improving obesity risk factors (45). It would be best to evaluate the effects of built environment change on community members, beyond the participants and their friends and family members—through community audits and sampling, particularly over the long-term (e.g., 5 to 10 years).

Strengths and Limitations

Evaluation of SHHC, with its hands-on, experiential learning focus combined with the social, built environment, and civic engagement components, make a novel contribution to the field. Strengths also include integration of three evidence-based programs, randomization of participants after recruitment and baseline measurements, and the inclusion of 16 rural, medically underserved communities with hard-to-reach populations. Use of existing infrastructure of cooperative Extension and rural healthcare systems is another notable strength of this study, as these partnerships hold potential for national dissemination.

Given the focus on medically underserved rural populations, it is possible our findings would not generalize to urban populations, although certainly aspects of limited healthcare access have universal implications and thus this program may indeed be appropriate and should be further evaluated in new settings. Another possible limitation is that the women in this study were more highly educated (48% with college education), compared to the average female residents in these rural towns (approximately 20%). Thus, the study population was not reflective of the overall town population in terms of education. However, 52% of the study population was of lower educational attainment, and sensitivity analyses found no differential intervention effects by education, which provides some assurance of the program’s relevance to the general population. Although the SHHC intervention group addressed aspects of their social and community environment, and HEART Clubs implemented changes through civic engagement initiatives, it was not the objective of this study to evaluate major built environment or policy changes. However, an important contribution to the field would be future studies specifically designed to evaluate civic engagement’s independent and additive effects.

CONCLUSIONS

Rural woman face unique challenges to living healthy lifestyles and are at greater risk for obesity CVD than other populations. Designing and evaluating effective programs that incorporate community-informed civic engagement initiatives holds important potential for health promotion for the participants and the broader community, as participants potentially act as powerful role models and agents of change for their families, friends, and communities (21). The SHHC curriculum was designed to meet this need, informed by extensive, multilevel formative data and implemented in partnership with local health educators in consideration of future dissemination feasibility. These findings demonstrate a clear potential for a multilevel approach with an experiential learning foundation. Future studies should include rigorous dissemination evaluation in a range of settings and populations. Additionally, longer-term follow-up post-intervention studies are needed to understand the durability of benefits observed.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this subject?

Rural women are at higher risk for cardiovascular disease and obesity than urban women.

Very few programs have actively engaged the individual, social, and environmental spheres of influence as a strategy to support behavior change.

What does this study add?

A twice-weekly program including individual, social, and environmental spheres of influence to help support improvements among cardiovascular disease factors, particularly body weight, demonstrated superior results to a once-monthly control program.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: This study was supported by grant R01 HL120702 from the National Institutes of Health and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The funders/sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We are grateful for the contribution of the health educators in Montana and New York, Jan Feist and Judy Ward for their programmatic support, and our National Advisory Board members for their contributions to this study.

Footnotes

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION: www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT02499731

DISCLOSURE: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: Dr. Seguin had access to the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Seguin, Folta, Nelson, Paul. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Seguin, Graham, Nelson, Folta, Diffenderfer, Eldridge, Strogatz. Drafting of the manuscript: Seguin, Graham, Eldridge. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Graham, Eldridge, Paul, Folta, Nelson, Diffenderfer, Strogatz, Parry. Statistical analysis: Graham, Parry. Obtained funding: Seguin, Folta, Nelson, Paul. Administrative, technical, or material support: Seguin, Graham, Nelson, Folta, Diffenderfer, Eldridge. Study supervision: Seguin, Paul, Graham, Diffenderfer, Strogatz.

Contributor Information

Rebecca A. Seguin, Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Lynn Paul, College of Education, Health and Human Development, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, USA.

Sara C. Folta, Friedman School of Nutrition, Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA

Miriam E. Nelson, Sustainability Institute, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA

David Strogatz, Center for Rural Community Health, Bassett Research Institute, Cooperstown, NY, USA.

Meredith Graham, Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Anna Diffenderfer, Montana Dietetic Internship, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, USA.

Galen Eldridge, Montana State University Extension, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, USA.

Stephen A. Parry, Cornell Statistical Consulting Unit, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

References

- 1.Heron M. National vital statistics reports. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. Deaths: Leading causes for 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cossman JS, James WL, Cosby AG, Cossman RE. Underlying causes of the emerging nonmetropolitan mortality penalty. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1417. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Connor A, Wellenius G. Rural-urban disparities in the prevalence of diabetes and coronary heart disease. Public Health. 2012;126:813–20. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett KJ, Olatosi B, Probst JC. Health disparities: a rural-urban chartbook. South Carolina Rural Health Research Center; 220 Stoneridge Dr., Ste 204, Columbia, SC 29210, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thornton L, Crawford D, Cleland V, Timperio A, Abbott G, Ball K. Do food and physical activity environments vary between disadvantaged urban and rural areas? Findings from the READI Study. Health Promot J Austr. 2012;23:153–6. doi: 10.1071/he12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michimi A, Wimberly MC. Natural environments, obesity, and physical activity in nonmetropolitan areas of the United States. J Rural Health. 2012;28:398–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen J. An integrative review of literature on the determinants of physical activity among rural women. Public Health Nurs. 2013;30:288–311. doi: 10.1111/phn.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren K, Mitten D, Loeffler T. Theory & Practice of Experiential Learning. Association for Experiential Education; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raynor HA, Champagne CM. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: interventions for the treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:129–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brand T, Pischke CR, Steenbock B, et al. What works in community-based interventions promoting physical activity and healthy eating? A review of reviews. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:5866–88. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110605866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sautkina E, Goodwin D, Jones A, et al. Lost in translation? Theory, policy and practice in systems-based environmental approaches to obesity prevention in the Healthy Towns programme in England. Health Place. 2014;29:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes.

- 13.Health Resources & Services Administration. [accessed Dec 30 2016];2016 Oct; Internet: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/shortage-designation/types.

- 14.Seguin RA, Eldridge G, Graham ML, Folta SC, Nelson ME, Strogatz D. Strong Hearts, healthy communities: a rural community-based cardiovascular disease prevention program. BMC Public Health. 2016:16. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2751-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seguin R, Heidkamp-Young E, Juno B, et al. Community-based participatory research pilot initiative to catalyze positive change in local food and physical activity environments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Annual Meeting Oral Presentation. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folta SC, Lichtenstein AH, Seguin RA, Goldberg JP, Kuder JF, Nelson ME. The StrongWomen-Healthy Hearts Program: reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors in rural sedentary, overweight, and obese midlife and older women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1271–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2008.145581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seguin R, Heidkamp-Young E, Kuder J, Nelson M. Improved physical fitness among older female participants in a nationally disseminated, community-based exercise program. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:183–90. doi: 10.1177/1090198111426768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siervo M, Lara J, Chowdhury S, Ashor A, Oggioni C, Mathers JC. Effects of the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:1–15. doi: 10.1017/s0007114514003341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture. Internet: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

- 20.Rees K, Hartley L, Flowers N, et al. ‘Mediterranean’ dietary pattern for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009825.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell K, Wilcox J, Clonan A, et al. The role of social networks in the development of overweight and obesity among adults: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2015:15. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomaselli GF, Harty M-B, Horton K, Schoeberl M. The American Heart Association and the Million Hearts Initiative: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;124:1795–9. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182327084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folsom AR, Yatsuya H, Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Cushman M, Rosamond WD. Community prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health, by the American Heart Association definition, and relationship with cardiovascular disease incidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1690–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s Strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2013:01. cir. 0000437741.48606. 98. [Google Scholar]

- 27.United States Department of Agriculture. Rural Classifications. http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications.aspx.

- 28.Chakraborty H, Gu H. RTI Press publication No MR-0009-0903. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2009. A mixed model approach for intent-to-treat analysis in longitudinal clinical trials with missing values. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu GHF, Lu KF, Mogg R, Mallick M, Mehrotra DV. Should baseline be a covariate or dependent variable in analyses of change from baseline in clinical trials? Stat Med. 2009;28:2509–30. doi: 10.1002/sim.3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khare MM, Koch A, Zimmermann K, Moehring PA, Geller SE. Heart Smart for Women: a community-based lifestyle change intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk in rural women. J Rural Health. 2014;30:359–68. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilstrap LG, Malhotra R, Peltier-Saxe D, et al. Community-based primary prevention programs decrease the rate of metabolic syndrome among socioeconomically disadvantaged women. J Womens Health. 2013;22:322–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devine CM, Farrell TJ, Hartman R. Sisters in health: experiential program emphasizing social interaction increases fruit and vegetable intake among low-income adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2005;37:265–70. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kandula NR, Dave S, De Chavez PJ, et al. Translating a heart disease lifestyle intervention into the community: the South Asian Heart Lifestyle Intervention (SAHELI) study; a randomized control trial. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2401-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arredondo EM, Haughton J, Ayala GX, et al. Fe en Accion/Faith in Action: Design and implementation of a church-based randomized trial to promote physical activity and cancer screening among churchgoing Latinas. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt B):404–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosamond WD, Ammerman AS, Holliday JL, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factor intervention in low-income women: the North Carolina WISEWOMAN project. Prev Med. 2000;31:370–9. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perry CK, Rosenfeld AG, Bennett JA, Potempa K. Heart-to-Heart: promoting walking in rural women through motivational interviewing and group support. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22:304–12. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000278953.67630.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Will JC, Massoudi B, Mokdad A, et al. Reducing risk for cardiovascular disease in uninsured women: combined results from two WISEWOMAN projects. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972) 2000;56:161–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin PD, Rhode PC, Dutton GR, Redmann SM, Ryan DH, Brantley PJ. A primary care weight management intervention for low-income African-American women. Obesity. 2006;14:1412–20. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duff EMW, Simpson SH, Whittle S, Bailey EY, Lopez SA, Wilks R. Impact on blood pressure control of a six-month intervention project. West Indian Med J. 2000;49:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss - the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johns DJ, Hartmann-Boyce J, Jebb SA, Aveyard P Behav Weight Management Review G. Weight change among people randomized to minimal intervention control groups in weight loss trials. Obesity. 2016;24:772–80. doi: 10.1002/oby.21255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson ND, Damianakis T, Kroeger E, et al. The benefits associated with volunteering among seniors: a critical review and recommendations for future research. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:1505–33. doi: 10.1037/a0037610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan LK, Sobush K, Keener D, et al. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(RR7):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renalds A, Smith TH, Hale PJ. A systematic review of built environment and health. Fam Community Health. 2010;33:68–78. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181c4e2e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matson-Koffman DM, Brownstein JN, Neiner JA, Greaney ML. A site-specific literature review of policy and environmental interventions that promote physical activity and nutrition for cardiovascular health: what works? Am J Health Promot. 2005;19:167–93. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.