Abstract

BACKGROUND

Maternal birth trauma to the pelvic floor muscles is thought to be consequent to mechanical demands placed on these muscles during fetal delivery that exceed muscle physiological limits. The above is consistent with studies of striated limb muscles that identify hyperelongation of sarcomeres, the functional muscle units, as the primary cause of mechanical muscle injury and resultant muscle dysfunction. However, pelvic floor muscles’ mechanical response to strains have not been examined at a tissue level. Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated that during pregnancy, rat pelvic floor muscles acquire structural and functional adaptations in preparation for delivery, which likely protect against mechanical muscle injury by attenuating the strain effect.

OBJECTIVES

1. To determine the mechanical impact of parturition-related strains on pelvic floor muscles’ microstructure. 2. To test the hypothesis that pregnancy-induced adaptations modulate muscle response to strains associated with vaginal delivery.

STUDY DESIGN

3-month-old Sprague-Dawley late-pregnant (N=20) and non-pregnant (N=22) rats underwent vaginal distention, replicating fetal crowning, with variable distention volumes. Age-matched uninjured pregnant and non-pregnant rats served as respective controls. After sacrifice, pelvic floor muscles, which include coccygeus, iliocaudalis, and pubocaudalis, were fixed in situ and harvested for fiber and sarcomere length measurements. To ascertain the extent of physiological strains during spontaneous vaginal delivery, analogous measurements were obtained in the intrapartum rats (N=4), sacrificed during fetal delivery. Data were compared with repeated measures and two-way analysis of variance, followed by pairwise comparisons, with significance set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Gross anatomic changes were observed in the pelvic floor muscles following vaginal distention, particularly in the entheseal region of pubocaudalis, which appeared translucent. The above appearance resulted from dramatic stretch of the myofibers, as indicated by significantly longer fiber length compared to controls. Stretch ratios, calculated as fiber length after vaginal distention divided by baseline fiber length, increased gradually with increasing distention volume. Paralleling these macroscopic changes, vaginal distention resulted in acute and progressive increase in sarcomere length with rising distention volume. The magnitude of strain effect varied by muscle, with the greatest sarcomere elongation observed in coccygeus, followed by pubocaudalis, and a smaller increase in iliocaudalis, observed only at higher distention volumes.

The average fetal rat volume approximated 3 mL. Pelvic floor muscle sarcomere lengths in pregnant animals undergoing vaginal distention with 3 mL were similar to the intrapartum sarcomere lengths in all muscles (P>0.4), supporting the validity of our experimental approach. Vaginal distention resulted in dramatically longer sarcomere lengths in non-pregnant compared to pregnant animals, especially in coccygeus and pubocaudalis (P<0.0001), indicating significant attenuation of sarcomere elongation in the presence of pregnancy-induced adaptations in pelvic floor muscles.

CONCLUSIONS

Delivery-related strains lead to acute sarcomere elongation, a well-established cause of mechanical injury in skeletal muscles. Sarcomere hyperelongation resultant from mechanical strains is attenuated by pregnancy-induced adaptations acquired by the pelvic floor muscles prior to parturition.

Keywords: pelvic floor muscles, birth injury, pregnancy adaptations, rat

INTRODUCTION

The pathways by which vaginal delivery leads to pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) are believed to be multifactorial, involving damage to nerves,1–3 connective tissue,4–7 and pelvic smooth and striated muscles.8–10 Clinical studies suggest that maternal trauma to the pelvic floor muscles (PFMs) results from mechanical demands imposed on these muscles during parturition that exceed skeletal muscle physiological limits.9 Hyperelongation of sarcomeres, muscle functional units, has been shown to be a primary cause of mechanical muscle injury and resultant muscle dysfunction in the other striated muscles.11–16 Prior studies have shown that significant limb muscle injury reliably occurs when muscle stretch exceeds 60% of resting muscle length.17 Such strains result in supraphysiologic sarcomere lengths at which actin and myosin filaments no longer overlap, in turn leading to myofibrillar disruption acutely and muscle dysfunction in the long-term.18,19

Computational models of human parturition demonstrate that PFMs’ elongation up to 300% of resting muscle length is necessary to achieve fetal delivery.20,21 Thus, muscle injury would be expected to occur in most, if not all, vaginal deliveries; however, the majority of women do not exhibit radiologically-detected PFM avulsion injuries after vaginal childbirth.22 Furthermore, despite a strong association between PFDs and postpartum PFM avulsions observed on imaging, a large subset of women with pelvic floor dysfunction exhibit decreased PFM strength but do not demonstrate this type of defect.8,22–26 These findings suggest that muscle injury other than avulsion tears may contribute to postpartum PFM dysfunction.

Our group previously identified a constellation of changes in rat PFMs during pregnancy, including fiber elongation via serial addition of sarcomeres, or sarcomerogenesis, and increase in intramuscular extracellular matrix collagen content and muscle stiffness.27,28 We hypothesized that these antepartum alterations enable PFMs to withstand deformations during parturition without excessive sarcomere hyperelongation, in turn, decreasing PFMs’ susceptibility to mechanical birth injury. Taken together, the above suggests that structural and functional adaptations, acquired by the PFMs during pregnancy, may account for the ability of these muscles to withstand “supraphysiologic” strains during parturition without injury. Thus, the objectives of the current study were twofold: 1) to determine the mechanical impact of delivery-related strains on PFM microstructure and 2) to test the hypothesis that pregnancy-induced adaptations of the PFMs modulate muscle response to strains associated with parturition by attenuating sarcomere elongation, the primary cause of mechanical injury in skeletal muscles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Given technical and ethical constraints associated with directly probing PFMs in living women, animal models are essential to study the mechanisms of PFMs’ birth injury at the tissue level. We chose to utilize the rat model for the following three reasons: 1) rat PFMs’ anatomy and architecture, the strongest predictor of in vivo active muscle function, are similar to those of humans;29,30 2) rat has proven to be a reliable exemplar to study tissue changes due to pregnancy;31–33 3) pregnancy induces unique adaptations in the intrinsic structural components of rat PFMs.27,28 The University of California San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all study procedures. Three-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats were utilized to determine the mechanical impact of delivery-related strains on the PFMs’ microstructure and to assess the effect of pregnancy-induced adaptations, acquired by the PFMs antepartum, on muscle response to mechanical strains. Primigravid gestational day 20–21 late-pregnant (P) (N=20) and nulligravid non-pregnant (NP) (N=22) animals underwent vaginal distention (VD), replicating fetal crowning, with balloon volumes ranging from 1–5 milliliters (mL).

To ascertain physiological strain during vaginal delivery, neonatal rat (N=13) bi-parietal and abdominal diameters were measured and spherical volumes were calculated using V = (4/3)*πr3 equation, with π = 3.14, r – radius, V – volume. To determine the impact of the strain imposed on the PFMs during spontaneous parturition and to confirm validity of our experimental approach, intrapartum rats (N=4) were sacrificed during vaginal delivery and the outcomes of interest were compared to pregnant animals undergoing vaginal distention with the 3 mL balloon volume, analogous to that of a neonatal rat. Age-matched P and NP rats (N=10/group) that did not undergo vaginal distention served as respective controls. NP animals were in similar parts of estrous cycle, as determined by vaginal smears.

Vaginal distention procedure

Animals were weighed and anesthetized using isoflurane gas mixed with oxygen delivered via nose cone for the duration of the procedure. Genital hiatus (GH; base of the external urethral meatus to posterior fourchette), total vaginal length (TVL), and perineal body (PB; posterior fourchette to mid-anus) were measured using digital calipers. Vaginal distention was performed utilizing 12 French transurethral balloon catheters (Bard Medical, Covington, GA) with 130 gram weight attached to the end of the catheter to simulate circumferential and downward distention. The catheter was placed intravaginally, inflated to varying volumes, and left in place for 1–2 hours, as previously described.34

Fiber length and sarcomere length measurements

Pregnant (P), non-pregnant (NP), and intrapartum rats were sacrificed and PFMs, including coccygeus (C), and pubocaudalis (PCa) and iliocaudalis (ICa), which comprise the levator ani muscle in rats,35 were fixed in situ to preserve in vivo architecture, harvested, and divided into three regions. Small fiber bundles, consisting of either 10–20 or 3–5 fibers, were microdissected from each region for fiber length (Lf) and sarcomere length (Ls) measurements, respectively, using previously described methods.27,36 Muscle stretch ratios were calculated by dividing fiber length after vaginal distention at each distention volume by the fiber length in the control groups.

Assesssment of muscle ultrastructure

In addition to the assessment of gross anatomy and sarcomere length measurements, PFMs’ ultrastructure was examined with transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Muscle specimens were prepared for TEM using a standard protocol that combines chemical fixation with embedding in Durcupan. Briefly, PFMs, harvested from perfusion-fixed animals, were immersed in modified Karnovsky’s fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.15 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4) for at least 4 hours, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.15 M cacodylate buffer for 1 hour and stained en bloc in 2% uranyl acetate for 1 hour. Samples were dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in Durcupan epoxy resin (Sigma-Aldrich), sectioned at 60 nm on a Leica UCT ultramicrotome, and picked up on Formvar and carbon-coated copper grids. Sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 5 minutes and Sato’s lead stain for 1 minute. Grids were viewed using a JEOL 1200EX II (JEOL, Peabody, MA) transmission electron microscope and photographed using a Gatan digital camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA).

Statistical considerations

Baseline characteristics were compared between P and NP animals using independent Student t-test. Comparisons between muscles and conditions were performed by repeated measures and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by pairwise comparisons with Šidák or Dunnett’s tests, as appropriate. Significance level (α) was set to 5%. To obtain 80% power (1-β) to detect a 15% difference, the sample size of 4/group/distention volume was calculated utilizing the equation: n=16*((CV)2/(ln(1-δ))2 using experimental variability in the control groups, with variables n=sample size; δ=difference desired (15%); CV=coefficient of variation (8%). Results are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM), except where noted. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.00, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA.

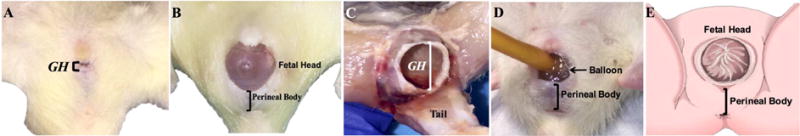

RESULTS

As expected, the baseline characteristics differed between the groups. Specifically, body weight of non-pregnant rats (209.3 ± 2.3 g) was lower than that of pregnant animals (284.9 ± 4.7 g), P<0.0001. Genital hiatus (NP: 3.9 ± 0.1 mm vs. P: 4.3 ± 0.1 mm, P=0.01); perineal body (NP: 7.6 ± 0.2 mm vs. P: 8.8 ± 0.3 mm, P=0.002); and total vaginal length (NP: 20.4 ± 0.3 mm vs. P: 24.4 ± 0.5 mm, P<0.0001) were also smaller in non-pregnant, compared to pregnant animals. GH increased dramatically during vaginal distention in both, NP (from 7.8 ± 0.3 mm at 1 mL to 16.3 ± 0.6 mm at 5 mL) and P (from 6.6 ± 0.4 mm at 1 mL to 14.4 ± 1.5 mm at 5 mL), groups. Interestingly, GH was substantially increased during spontaneous vaginal delivery, ranging from 10.7 to 13.6 mm in the intrapartum rats (median 13.1; mean 12.6 ± 0.7, P<0.0001 relative to the antepartum values (Figure 1)).

Figure 1.

Rat genital hiatus (GH) before delivery (A) is markedly increased during fetal delivery (B, C) and vaginal distention procedure (D), demonstrating similarity to the human parturition (E).

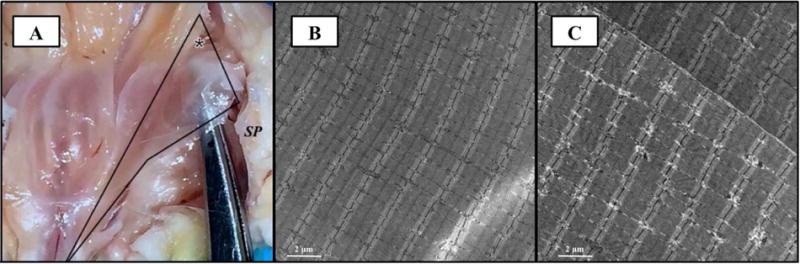

Departure from normal muscle structural organization in response to vaginal distention was evident from the dramatic changes in the PFMs’ gross appearance, as well as the distortion of Z-lines and misalignment of adjacent sarcomeres, visualized by TEM (Figure 2). These changes were mainly observed in the PCa and C, but were much less pronounced in ICa. PCa was noted to be extremely attenuated, with an almost translucent appearance of its entheseal region at distention volumes > 2 mL (Figure 2A). Similar distortion was noted in C, while alterations in ICa appearance were less prominent, indicating variability in the magnitude of strain impact across the individual components of the PFM complex. These gross changes corresponded to a dramatic stretch of the myofibers, as evident by significant increase in PFM fiber length with VD compared to controls (Table 1). As expected, PFM stretch ratios increased progressively with the increase in strain. The largest stretch ratios across distention volumes were observed in C, which has the shortest resting fiber length fibers relative to the other PFMs (1.4–1.8 in NP and 1.2–1.7 in P). Analogous to the pubococcygeus component of the levator ani complex that is predicted to experience the highest strains during human vaginal delivery,20 PCa stretch ratios (1.2–1.7 in NP and 1.1–1.5 in P) exceeded those in ICa (1.2–1.4 in NP and 1.1–1.3 in P), Table 1.

Figure 2.

(A) Photograph of left pubocaudalis fixed in situ during vaginal distention procedure. The instrument is visible through the translucent entheseal region (asterisk). Analogous appearance of pubocaudalis was noted during spontaneous fetal delivery. SP: symphysis pubis has been disarticulated to aid with visualization of the pelvic floor muscles. Transmission electron microscopy images of pubocaudalis muscles, procured from control (B) and vaginal distention with 5 mL volume (C) groups. Significant departure from normal muscle microstructure, specifically distortion and smearing of Z-lines and misalignment of adjacent sarcomeres, is observed in response to parturition-related strains (C).

Table 1.

Changes in pelvic floor muscles’ fiber length (Lf) in response to vaginal distention (VD) in non-pregnant (NP) and pregnant (P) groups. Stretch ratios are calculated as fiber length after vaginal distention divided by fiber length in respective controls (0 mL). Measurements in millimeters (mm) are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

| Distention volume (mL) | Non-pregnant (Lf, mm) | N | Stretch Ratio | P-valuea NP+VD vs NP control | Pregnant (Lf, mm) | N | Stretch Ratio | P-valuea P+VD vs P control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Coccygeus | ||||||||

| 0 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 10 | – | – | 10.5 ± 0.3 | 10 | – | – |

| 1 | 10.8 ± 0.2 | 4 | 1.4 | 0.01 | 12.9 ± 0.8 | 4 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 11.9 ± 1.2 | 4 | 1.5 | 0.0005 | 13.2 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.3 | 0.02 |

| 3 | 13.1 ± 1.2 | 5 | 1.7 | <0.0001 | 13.4 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.3 | 0.0006 |

| 4 | 13.5 ± 1.1 | 4 | 1.7 | <0.0001 | 14.6 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | 14.1 ± 0.8 | 5 | 1.8 | <0.0001 | 17.3 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.7 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Pubocaudalis | ||||||||

| 0 | 16.2 ± 0.4 | 10 | – | – | 19.6 ± 0.4 | 10 | – | – |

| 1 | 19.4 ± 0.9 | 4 | 1.2 | 0.01 | 21.3 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 22.0 ± 0.1 | 4 | 1.4 | <0.0001 | 23.2 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.2 | 0.001 |

| 3 | 24.6 ± 1.1 | 5 | 1.5 | <0.0001 | 25.4 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.3 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | 26.5 ± 1.6 | 4 | 1.6 | <0.0001 | 26.3 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.3 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | 27.9 ± 0.7 | 5 | 1.7 | <0.0001 | 28.7 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.5 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Iliocaudalis | ||||||||

| 0 | 14.8 ± 0.2 | 10 | – | – | 18.0 ± 0.5 | 10 | – | – |

| 1 | 17.2 ± 0.9 | 4 | 1.2 | 0.08 | 20.3 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.1 | 0.07 |

| 2 | 18.0 ± 0.7 | 4 | 1.2 | 0.01 | 20.2 ± 0.7 | 4 | 1.1 | 0.08 |

| 3 | 20.6 ± 0.8 | 5 | 1.4 | <0.0001 | 21.9 ± 0.7 | 4 | 1.2 | 0.0005 |

| 4 | 20.8 ± 0.9 | 4 | 1.4 | <0.0001 | 23.2 ± 0.3 | 4 | 1.3 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | 21.2 ± 0.9 | 5 | 1.4 | <0.0001 | 23.9 ± 0.4 | 4 | 1.3 | <0.0001 |

P-values derived from repeated measures 2-way analysis of variance, followed by pairwise comparisons with respective controls using Dunnett’s test.

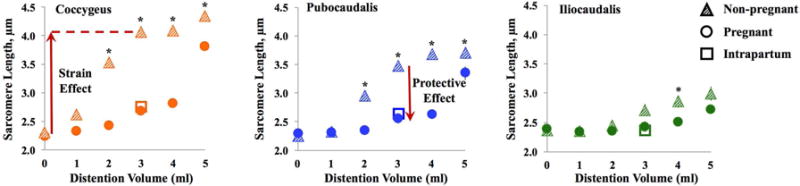

Paralleling gross anatomic and macroscopic findings, VD resulted in acute and progressive increase in Ls with rising distention volume. The magnitude of strain effect on Ls also varied by muscle, with the greatest change observed in C, followed by PCa, and a smaller increase in ICa, observed only at higher distention volumes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Within-group comparisons of the pelvic floor muscles’ sarcomere length (Ls) in response to mechanical strains induced by vaginal distention with varying volumes (1–5mL) in non-pregnant and pregnant animals, relative to respective controls. Measurements in micrometers (μm) are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

| Distention volume (mL) | Non-pregnant (Ls, μm) | N | aP-value | Pregnant (Ls, μm) | N | aP-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Coccygeus | ||||||

| Control | 2.3 ± 0.06 | 10 | – | 2.25 ± 0.06 | 10 | – |

| 1 | 2.61 ± 0.07 | 4 | 0.04 | 2.4 ± 0.03 | 4 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 3.53 ± 0.03 | 4 | < 0.0001 | 2.57 ± 0.09 | 4 | 0.001 |

| 3 | 3.95 ± 0.11 | 5 | < 0.0001 | 2.68 ± 0.07 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

| 4 | 4.07 ± 0.11 | 4 | < 0.0001 | 2.8 ± 0.08 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

| 5 | 4.49 ± 0.19 | 5 | < 0.0001 | 3.65 ± 0.08 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

|

Pubocaudalis | ||||||

| Control | 2.25 ± 0.04 | 10 | – | 2.3 ± 0.04 | 10 | – |

| 1 | 2.42 ± 0.07 | 4 | 0.45 | 2.31 ± 0.01 | 4 | 0.99 |

| 2 | 2.92 ± 0.07 | 4 | < 0.0001 | 2.47 ± 0.08 | 4 | 0.17 |

| 3 | 3.5 ± 0.05 | 5 | < 0.0001 | 2.6 ± 0.03 | 4 | 0.003 |

| 4 | 3.69 ± 0.01 | 4 | < 0.0001 | 2.72 ± 0.08 | 4 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | 3.84 ± 0.13 | 5 | < 0.0001 | 3.32 ± 0.12 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

|

Iliocaudalis | ||||||

| Control | 2.36 ± 0.04 | 10 | – | 2.39 ± 0.04 | 10 | – |

| 1 | 2.37 ± 0.08 | 4 | 0.99 | 2.36 ± 0.02 | 4 | 0.99 |

| 2 | 2.53 ± 0.07 | 4 | 0.45 | 2.37 ± 0.04 | 4 | 0.99 |

| 3 | 2.64 ± 0.09 | 5 | 0.046 | 2.46 ± 0.05 | 4 | 0.87 |

| 4 | 2.86 ± 0.12 | 4 | 0.0002 | 2.49 ± 0.02 | 4 | 0.64 |

| 5 | 3.02 ± 0.11 | 5 | < 0.0001 | 2.79 ± 0.1 | 4 | <0.0001 |

P-values derived from repeated measures 2-way (muscle × distention volume) analysis of variance, followed by pairwise comparisons with the respective controls using Dunnett’s test.

To confirm that Ls increase in response to strains induced by VD is representative of the mechanical impact of physiological strains placed on the PFMs during spontaneous vaginal delivery, we compared PFM Ls during fetal delivery to antepartum Ls values in the respective muscles of P animals. Analogous to our findings in P rats undergoing VD, Ls increased in all PFMs during vaginal delivery compared to antepartum values. Moreover, the extent of intrapartum Ls elongation exhibited similar variation across the individual PFMs. The largest Ls increase (24.4%) occurred in C: 2.25 ± 0.06 μm antepartum vs. 2.8 ± 0.04 μm intrapartum, P<0.0001. In PCa, Ls increased by 15.2%, from 2.3 ± 0.04 μm antepartum to 2.65 ± 0.04 μm intrapartum, P=0.0001. In contrast, the 5% increase in ICa Ls was not significantly different from the antepartum length of 2.39 ± 0.04 μm, compared to 2.51 ±0.04 μm intrapartum, P=0.3.

Using the equations outlined above, we calculated fetal rat volume, which approximated 3 mL (2.93 ± 0.1 mL). Importantly, Ls resultant from PFM strains induced by VD with 3 mL balloon volume did not differ from the intrapartum values in any of the muscles (P>0.4), Figure 3. The above findings support the validity of our experimental approach in replicating physiologic PFM strain during vaginal delivery.

Figure 3.

Vaginal distention (VD) with 1–5 mL volumes resulted in progressive sarcomere elongation (strain effect). Increase in sarcomere length was attenuated in pregnant, compared to non-pregnant rats (protective effect due to pregnancy-induced adaptations), especially in coccygeus and pubocaudalis. Distention with 3 mL in pregnant rats resulted in sarcomere length analogous to the intrapartum values.

To determine if structural and functional alterations acquired by the PFMs during pregnancy27,28 modulate PFM response to strain, we compared PFM Ls of NP and P rats at each distention volume between 1–5 mL (Figure 3). VD with 3 mL volume, analogous to physiologic intrapartum strain, resulted in dramatically longer C and PCa Ls in NP compared to P animals, P<0.0001 (Table 3). In contrast, the difference in ICa Ls between NP and P rats was not significant (P=0.07). When evaluating the pattern of sarcomere lengthening across strain levels, C and PCa Ls were significantly longer in NP compared to P animals at all volumes above 1 mL. In contrast, there was no significance difference in in ICa Ls between NP and P rats with smaller strains. However, VD with volumes > 3 mL, which approximates average fetal rat volume, resulted in significantly increased Ls in NP compared to P animals (P<0.01) in all muscles.

Table 3.

Comparisons between non-pregnant and pregnant groups, demonstrating a differential response of the pelvic floor muscles’ sarcomere lengths (Ls) to vaginal distention with varying volumes. Distention volume of 0 milliliters (mL) corresponds to control animals. Measurements in micrometers (μm) are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

| Distention volume (mL) | Non-pregnant (Ls, μm) | N | Pregnant (Ls, μm) | N | aP-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Coccygeus | |||||

| 0 | 2.3 ± 0.06 | 10 | 2.25 ± 0.06 | 10 | 0.99 |

| 1 | 2.61 ± 0.07 | 4 | 2.4 ± 0.03 | 4 | 0.64 |

| 2 | 3.53 ± 0.03 | 4 | 2.57 ± 0.09 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

| 3 | 3.95 ± 0.11 | 5 | 2.68 ± 0.07 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

| 4 | 4.07 ± 0.11 | 4 | 2.8 ± 0.08 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

| 5 | 4.49 ± 0.19 | 5 | 3.65 ± 0.08 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

|

Pubocaudalis | |||||

| 0 | 2.25 ± 0.04 | 10 | 2.3 ± 0.04 | 10 | 0.99 |

| 1 | 2.42 ± 0.07 | 4 | 2.31 ± 0.01 | 4 | 0.9 |

| 2 | 2.92 ± 0.07 | 4 | 2.47 ± 0.08 | 4 | 0.0006 |

| 3 | 3.5 ± 0.05 | 5 | 2.6 ± 0.03 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

| 4 | 3.69 ± 0.01 | 4 | 2.72 ± 0.08 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

| 5 | 3.84 ± 0.13 | 5 | 3.32 ± 0.12 | 4 | < 0.0001 |

|

Iliocaudalis | |||||

| 0 | 2.36 ± 0.04 | 10 | 2.39 ± 0.04 | 10 | 0.99 |

| 1 | 2.37 ± 0.08 | 4 | 2.36 ± 0.02 | 4 | 0.99 |

| 2 | 2.53 ± 0.07 | 4 | 2.37 ± 0.04 | 4 | 0.61 |

| 3 | 2.64 ± 0.09 | 5 | 2.46 ± 0.05 | 4 | 0.42 |

| 4 | 2.86 ± 0.12 | 4 | 2.49 ± 0.02 | 4 | 0.008 |

| 5 | 3.02 ± 0.11 | 5 | 2.79 ± 0.1 | 4 | 0.17 |

P-values derived from two-way (group × distention volume) analysis of variance, followed by pairwise comparisons using Šidák correction.

COMMENT

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine PFMs’ response to strains associated with parturition on a microscopic level. The main findings of the current study demonstrate that delivery-related strains result in acute sarcomere elongation, a well-established cause of mechanical injury in other skeletal muscles.11–16 Although directly probing PFMs is not possible in pregnant women, published studies utilizing computational modeling provide invaluable data on differential strains placed on the individual components of the human levator ani complex during vaginal delivery, with the largest stretch ratios occurring in the entheseal region of the pubococcygeus, at its origin on the inner surface of the pubic ramus.20 This entheseal region has also been identified in imaging studies as a characteristic “injury zone” for avulsion-type injuries of the levator ani at childbirth.37,38 This region corresponds to the exact location at which the greatest degree of macroscopic and microstructural damage among the muscles comprising rat levator ani (PCa and ICa) was noted in our study. Furthermore, prior studies demonstrate a direct relationship between infant head size and degree of muscle stretch,20 concordant with our findings of increased sarcomere elongation with higher distention volumes.

Importantly, the current experimental results support our hypothesis that pregnancy-induced adaptations of the PFMs modulate muscle response to strains associated with parturition by attenuating sarcomere hyperelongation and, thus, appear to be protective. Interestingly, the differential extent of sarcomere lengthening in response to strain between pregnant and non-pregnant animals was most profound at the distention volume corresponding to the physiological strains placed on the PFMs during vaginal delivery (3 mL, analogous to average pup size). This may represent the “tipping point” beyond which the adaptations acquired by the PFMs during pregnancy are insufficient to protect these muscles against the mechanical impact of strain, as evident from smaller differences in sarcomere length between P and NP groups at higher distention volumes. Based on these findings, we propose that mechanical strains that exceed pregnancy-induced adaptations cause pathologic sarcomere lengthening, thus contributing to PFM injury and postpartum muscle dysfunction.

We have previously shown that structural and functional alterations acquired by different PFMs during pregnancy are not uniform; namely, C undergoes the greatest degree of fiber length elongation (via addition of sarcomeres in series), while PCa has the largest increase in stiffness, which is unaltered in ICa.27,28 Another interesting finding of the current investigation is that each individual PFM – C, PCa, and ICa – is exposed to a different degree of mechanical strain during both spontaneous vaginal delivery and the experimental vaginal distention procedure, with C and PCa subjected to larger strains compared to ICa.

The limitations of our study are inherent to the use of animal models to represent human conditions. As such, it remains unknown whether mechanical PFM injury due to excessive sarcomere hyperelongation is one of the PFM birth injury mechanisms in women. However, given the obvious ethical constraints associated with directly probing PFMs in pregnant women, animal models are essential to expand our understanding of the impact of pregnancy and vaginal delivery on the PFMs’ structural components.

In the current study, vaginal distention in the rat model did not lead to PFM avulsions. However, our findings of near-translucent appearance of certain parts of the PFMs – particularly the PCa entheseal region – support the notion that variable phenotypes of maternal PFM trauma likely exist.8,39 It is conceivable that if analogous PFM myofiber stretch occurs during vaginal delivery in some women, the resultant “see-through” appearance would likely be indistinguishable from muscle avulsion injuries on imaging. The above may explain the recently published findings that a large proportion of levator ani avulsions observed shortly after childbirth were no longer evident at 1 year postpartum.40 It appears that variable phenotypes of the PFMs’ birth injury possibly exist. For instance, in some cases, irreversible damage to the myofibers may occur due to myofibrillar disruption associated with sarcomere hyperelongation, while in other cases, the regions of the pelvic floor muscles most affected by strains could avulse. The rat has proven to be a useful model for studies of pregnancy and delivery-induced changes in the pelvic floor.28,32–34 Furthermore, the architectural design of rat PFMs closely approximates human PFM architecture.29,30 Importantly, the rat PFMs acquire structural and functional adaptations during pregnancy.27,28 The plasticity of rat PFMs allows the investigations of the protective effects of pregnancy-induced muscle adaptations.

The current experimental approach necessitates euthanasia of each animal at the time of vaginal distention. Thus, we were not able to follow the same animal longitudinally. Instead, we had to rely on cross-sectional examination of animals from each group and assumed homogeneity among individual animals. Although this was a necessary constraint of our study design, Sprague-Dawley rats are widely used in many domains of biomedical research in general and, specifically, in studies of simulated birth injury.41–43 Furthermore, the rats utilized in this study were obtained from a single vendor, were age-matched, and in many cases were from the same litter. In addition, the animals were housed together (5/cage) to minimize potential impact of environmental variables and to assure concordant estrous cycle stage in non-pregnant animals. Finally, our study was adequately powered to detect a 15% difference in Ls, which was achieved in the C and PCa muscles. However, substantially smaller Ls changes occurred in the ICa. Our post-hoc analysis of power to detect difference in ICa Ls between the groups is as follows: 62% at 2 mL (effect size 6.8%); 76% at 3mL (effect size 7.5%); 96% at 4mL (effect size 15%), and 44% at 5 mL (effect size of 8%). Thus, it is possible that the difference in ICa Ls with 2, 3 and 5 mL distention volumes between the groups may have become significant with larger sample size.

In conclusion, excessive mechanical strain during parturition results in sarcomere hyperelongation, a well-established cause of mechanical skeletal muscle injury. The findings of the current study support our hypothesis that adaptations acquired by rat PFMs during pregnancy modulate muscle response to strains by attenuating the extent of sarcomere elongation. Our future studies will focus on confirming that acute sarcomere hyperelongation at larger strains leads to pathological alterations of the pelvic floor muscles long-term.

Condensation.

Rat pelvic floor muscles’ mechanical response to parturition-related strains, resultant in sarcomere hyperelongation, is modulated by pregnancy-induced adaptations, acquired by these muscles prior to delivery.

Implications and Contributions.

We demonstrated that mechanical strains related to parturition result in acute sarcomere hyperelongation of rat pelvic floor muscles. This well-established cause of mechanical injury in the limb muscles, represents a novel mechanism of birth trauma to the pelvic floor muscles, complementing previously studied avulsion-type injuries.

Pregnancy-induced adaptations in the contractile and extracellular matrix pelvic floor muscle components, previously identified by our group, appear to prepare these muscles to withstand “supraphysiological” strains during delivery by attenuating sarcomere hyperelongation and protecting against mechanical muscle injury.

The protective effect of pregnancy is greatest at the distention volume corresponding to average fetal size. At higher volumes, this protective effect is diminished, potentially indicating a “tipping point” beyond which pregnancy-induced adaptations are no longer sufficient to protect against maternal pelvic floor muscle injury.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The authors gratefully acknowledge funding by NIH/NICHD R01 HD092515 for the conduct of this research.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PFDs

pelvic floor disorders

- PFMs

pelvic floor muscles

- P

pregnant

- NP

non-pregnant

- VD

vaginal distention

- GH

genital hiatus

- TVL

total vaginal length

- PB

perineal body

- C

coccygeus

- ICa

iliocaudalis

- PCa

pubocaudalis

- Lf

muscle fiber length

- Ls

sarcomere length

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Portions of this work have been presented and awarded the Best Resident/Fellow Paper and Best in Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Basic Science Category Awards at the 2016 American Urogynecologic Society’s and 2017 International Continence Society’s annual meetings, respectively.

Contributor Information

Tatiana CATANZARITE, San Diego, California. Department of Reproductive Medicine, Division of Urogynecology and Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery, University of California, San Diego.

Mrs. Shannon BREMNER, San Diego, California. Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of California, San Diego.

Ms. Caitlin L. BARLOW, San Diego, California. Department of Reproductive Medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Ms. Laura BOU-MALHAM, San Diego, California. Department of Reproductive Medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Shawn O’CONNOR, San Diego, California. School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego State University.

Marianna ALPERIN, San Diego, California. Department of Reproductive Medicine, Division of Urogynecology and Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery, University of California, San Diego.

References

- 1.Snooks SJ, Swash M, Mathers SE, Henry MM. Effect of vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor: a 5-year follow-up. Br J Surg. 1990;77(12):1358–60. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snooks SJ, Swash M, Henry MM, Setchell M. Risk factors in childbirth causing damage to the pelvic floor innervation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1986;1(1):20–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01648831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen RE, Hosker GL, Smith AR, Warrell DW. Pelvic floor damage and childbirth: a neurophysiological study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97(9):770–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb02570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zong W, Jallah ZC, Stein SE, Abramowitch SD, Moalli PA. Repetitive mechanical stretch increases extracellular collagenase activity in vaginal fibroblasts. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2010;16(5):257–62. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3181ed30d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahn DD, Ruff MD, Brown SA, Tibbals HF, Word RA. Biomechanical properties of the vaginal wall: effect of pregnancy, elastic fiber deficiency, and pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(5):590.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budatha M, Silva S, Montoya TI, et al. Dysregulation of protease and protease inhibitors in a mouse model of human pelvic organ prolapse. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Memon HU, Handa VL. Vaginal childbirth and pelvic floor disorders. Womens Health. 2013;9(3):265–77. doi: 10.2217/whe.13.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietz HP, Wilson PD. Childbirth and pelvic floor trauma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19(6):913–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bortolini MA, Drutz HP, Lovatsis D, Alarab M. Vaginal delivery and pelvic floor dysfunction: current evidence and implications for future research. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(8):1025–30. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parente MP, Jorge RM, Mascarenhas T, Fernandes AA, Martins JA. Deformation of the pelvic floor muscles during a vaginal delivery. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19(1):65–71. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macpherson PCD, Dennis RG, Faulkner JA. Sarcomere dynamics and contraction-induced injury to maximally activated single muscle fibres from soleus muscles of rats. J Physiol. 1997;500(2):523–33. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macpherson PC, Schork MA, Faulkner JA. Contraction-induced injury to single fiber segments from fast and slow muscles of rats by single stretches. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(5 Pt 1):C1438–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon AM, Huxley AF, Julian FJ. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1966;184(1):170–92. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Telley IA, Denoth J. Sarcomere dynamics during muscular contraction and their implications to muscle function. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2007;28(1):89–104. doi: 10.1007/s10974-007-9107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren GL, Hayes DA, Lowe DA, Armtrong RB. Mechanical factors in the initiation of eccentric contraction-induced injury in rat soleus muscle. J Physiol. 1993;464:457–75. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieber RL, Fridén J. Mechanisms of muscle injury gleaned from animal models. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(11 Suppl):S70–9. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200211001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks SV, Zerba E, Faulkner JA. Injury to muscle fibres after single stretches of passive and maximally stimulated muscles in mice. J Physiol. 1995;488(Pt 2):459–69. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan DL. New insights into the behavior of muscle during active lengthening. Biophys J. 1990;57(2):209–21. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82524-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan DL, Proske U. Sarcomere popping requires stretch over a range where total tension decreases with length. J Physiol. 2006;574(Pt 2):627–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.574201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lien KC, Mooney B, DeLancey JO, Ashton-Miller JA. Levator ani muscle stretch induced by simulated vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(1):31–40. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000109207.22354.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoyte L, Damaser MS, Warfield SK, et al. Quantity and distribution of levator ani stretch during simulated vaginal childbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(2):198.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeLancey JO, Kearney R, Chou Q, Speights S, Binno S. The appearance of levator ani muscle abnormalities in magnetic resonance images after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02465-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dietz HP, Simpson JM. Levator trauma is associated with pelvic organ prolapse. BJOG. 2008;115(8):979–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeLancey JO, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, et al. Comparison of levator ani muscle defects and function in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):295–302. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250901.57095.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S, Wong V, Moore KH. Why are some women with pelvic floor dysfunction unable to contract their pelvic floor muscles? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53(6):574–9. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steensma AB, Konstantinovic ML, Burger CW, De Ridder D, Timmerman D, Deprest J. Prevalence of major levator abnormalities in symptomatic patients with an underactive pelvic floor contraction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(7):861–867. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1111-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alperin M, Lawley DM, Esparza MC, Lieber RL. Pregnancy-induced adaptations in the intrinsic structure of rat pelvic floor muscles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):191.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alperin M, Kaddis T, Pichika R, Esparza MC, Lieber RL. Pregnancy-induced adaptations in intramuscular extracellular matrix of rat pelvic floor muscles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(2):210.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alperin M, Tuttle LJ, Conner BR, et al. Comparison of pelvic muscle architecture between humans and commonly used laboratory species. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(11):1507–15. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2423-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart AM, Cook MS, Esparza MC, Slayden OD, Alperin M. Architectural assessment of rhesus macaque pelvic floor muscles: comparison for use as a human model. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(10):1527–35. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3303-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alperin M, Feola A, Duerr R, Moalli P, Abramowitch S. Pregnancy and delivery-induced biomechanical changes in rat vagina persist postpartum. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(9):1169–74. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1149-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowder JL, Debes KM, Moon DK, Howden N, Abramowitch SD, Moalli PA. Biomechanical adaptations of the rat vagina and supportive tissues in pregnancy to accommodate delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(1):136–43. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250472.96672.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daucher JA, Clark KA, Stolz DB, Meyn LA, Moalli PA. Adaptations of the rat vagina in pregnancy to accommodate delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(1):128–35. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000246798.78839.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alperin M, Feola A, Meyn L, Duerr R, Abramowitch S, Moalli P. Collagen scaffold: a treatment for simulated maternal birth injury in the rat model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(6):589.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bremer RE, Barber MD, Coates KW, Dolber PC, Thor KB. Innervation of the levator ani and coccygeus muscles of the female rat. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;275(1):1031–41. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lieber RL, Yeh Y, Baskin RJ. Sarcomere length determination using laser diffraction. Effect of beam and fiber diameter. Biophys J. 1984;45(5):1007–16. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84246-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J, Betschart C, Ramanah R, Asthon-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Anatomy of the Pubovisceral Muscle Origin: Macroscopic and Microscopic Findings within the Injury Zone. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(8):1–14. doi: 10.1002/nau.22649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Margulies RU, Huebner M, DeLancey JO. Origin and insertion points involved levator ani muscle defects. Am J Obs Gynecol. 2007;196(3):251.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.10.894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller JM, Low LK, Zielinski R, Smith AR, Delancey JO, Brandon C. Evaluating maternal recovery from labor and delivery: bone and levator ani injuries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):188.e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Delft KW, Thakar R, Sultan AH, IntHout J, Kluivers KB. The natural history of levator avulsion one year following childbirth: a prospective study. BJOG. 2015;122(9):1266–73. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan HQ, Kerns JM, Lin DL, Liu S, Esparza N, Damaser MS. Increased duration of simulated childbirth injuries results in increased time to recovery. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292(4):R1738–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00784.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Damaser MS, Broxton-King C, Ferguson C, Kim FJ, Kerns JM. Functional and neuroanatomical effects of vaginal distention and pudendal nerve crush in the female rat. J Urol. 2003;170(3):1027–31. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000079492.09716.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin AS, Carrier S, Morgan DM, Lue TF. Effect of simulated birth trauma on the urinary continence mechanism in the rat. Urology. 1998;52(1):143–51. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]