Abstract

Objectives

Elevated Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor auto-antibodies (GM-CSF Ab) are associated with increased intestinal permeability and stricturing behavior in Crohn’s Disease (CD). We tested for familial association of serum GM-CSF Ab level in CD and Ulcerative Colitis (UC) families.

Methods

Serum GM-CSF Ab concentration was determined in 230 pediatric CD probands and 404 of their unaffected parents and siblings, and 45 UC probands and 71 of their unaffected parents and siblings. A linear mixed effects model was used to test for familial association. The Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to determine the degree of association of the serum GM-CSF Ab level within families in comparison to the degree of association among families.

Results

The median (IQR) serum GM-CSF Ab concentration was higher in CD probands than in UC probands (1.5(0.5,5.4) mcg/mL versus 0.7(0.3,1.6) mcg/mL, p=0.0002). The frequency of elevated serum GM-CSF Ab concentration ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL was increased in unaffected siblings of CD probands with elevated GM-CSF Ab, compared to unaffected siblings of CD probands without elevated GM-CSF Ab (33% versus 13%, respectively, p=0.04). A similar result was observed within UC families. In families of CD patients, the mean (95th CI) ICC was equal to 0.153 (0.036,0.275), p=0.001, while in families of UC patients, the mean (95th CI) ICC was equal to 0.27(0.24,0.31), p=0.047.

Conclusions

These data confirmed familial association of serum GM-CSF Ab levels. This could be accounted for by either genetic or environmental factors shared within the family.

Keywords: Crohn’s Disease, heritability, serology, Ulcerative Colitis

Introduction

The Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD) are thought to be caused by multifactorial interactions between genetic,microbial, and environmental factors. Neutralizing Granulocyte Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor autoantibodies (GM-CSF Ab) reduce neutrophil antimicrobial function and cause progressive lung injury in Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis1. In Crohn’s Disease (CD), we have reported that elevated GM-CSF Ab are associated with increased intestinal permeability, stricturing ileal disease, and higher rates of surgery2,3. Moreover, GM-CSF Ab increase prior to increases in inflammatory biomarkers including CRP or fecal calprotectin and flares of active disease4. This suggests an environmental effect upon GM-CSF Ab levels. However, it is not known whether the GM-CSF Ab level is a familial trait or acquired immune parameter without association with genetic variation or shared environmental factors.

Antibodies directed against Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ASCA), Escherichia coli (anti-OmpC), and flagellin (anti-CBir1) are serologic markers associated with different phenotypes of IBD. Both the number of positive immune responses to these microbial antigens and magnitude of titer elevation are associated with complicated CD. Similar to high GM-CSF Ab levels, high ASCA titers are associated with early onset, stricturing and penetrating disease, need for small bowel surgery, and risk for early surgery in CD5,6.

Despite significant advances in our understanding of the genetic architecture of IBD risk over the past decade, the link between genetic variation and specific clinically important endophenotypes is poorly understood. An exception to this are several studies which have reported genetic variants associated with antimicrobial serologies in CD7–15. Increased expression of pANCA has been demonstrated in unaffected relatives of UC patients, and familial expression of ASCA and OmpC has been demonstrated in families of patients with CD12,13. These studies were conducted in families of predominantly adult patients. It is likely that many genetic loci which influence IBD risk and/or behavior function as quantitative trait loci, to regulate gene expression, or other quantitative traits16,17. This may include genetic regulation of serum cytokine Ab levels as a quantitative immune trait. We therefore tested for the strength of association for serum GM-CSF Ab level within CD and UC families. We aimed to determine whether serum GM-CSF Ab level is a familial trait in families of pediatric CD and UC patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Ethical Considerations

Patients diagnosed with CD or UC between 5 and 18 years of age and their first degree relatives (parents and siblings) were recruited at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and Emory University. Eight of the CD probands and 2 of the UC probands had a relative with IBD who was included in the study. As the numbers are small, we did not treat diseased siblings differently in the analysis. The first degree relatives were otherwise healthy without chronic illnesses. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and Emory University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants 18 years of age and older at the time of recruitment and from one of their parents for all participants under 18 years of age. Assent was also obtained from study subjects age 11 and older. Serum aliquots were obtained from probands and first degree relatives.

Serum GM-CSF Ab, IgG, and CRP ELISAs

Serum GM-CSF Ab levels were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously reported. The precision of the GM-CSF Ab assay ranges from 1.9% to 3.4% over the range of serum GM-CSF Ab detected18. The lower limit of quantification of the assay is 0.001 mcg/mL 18. Assay specificity was confirmed by showing that no signal was detected in IgG-depleted serum, or IgG-depleted serum containing each IgG immunoglobulin subclass 18. Total serum IgG was measured by ELISA in duplicate utilizing reagents from Sigma including: goat anti-Human IgG coating antibody - Sigma I2136; human IgG standard - Sigma I2511, and biotinylated goat anti-human IgG - Sigma B114018. Serum CRP was measured by ELISA in duplicate as per the manufacturer’s protocol (R&D Systems CRP Quantikine ELISA Kit, sensitivity 0.022 ng/mL, intra-assay precision 3.8%–8.3%, inter-assay precision 6%–7%).

Analysis of Familial Aggregation

Summary statistics for serum GM-CSF Ab levels included median(IQR) and frequency of values ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL in parents, probands, and siblings. Differences between groups were tested using the Mann-Whitney test, the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, or the χ2 test, as indicated in the Figure or Table legends. Results with p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Since continuous data analysis for familial association assumes normality of the data, base 10 log transformation was performed on the serum GM-CSF Ab levels so that the data would approximate the normal distribution. We analyzed the GMCSF Ab data on the log base 10 scale (or log based 10 transformed data) using a linear mixed effects model to test for familial association. Due to the log transformation, the estimated means, once converted back to the original scale, correspond to medians. The Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) is defined as the proportion of variance explained by familial resemblance with the total variance given by the sum of variance among families (σ2B) and within families (σ2W): t* = σ2B/(σ2B + σ2W).

An ICC for serum GM-CSF Ab levels was used to determine the degree of familial association of GM-CSF Ab levels within each group with the ICC indicating the percent of variation in GM-CSF Ab level accounted for by factors shared within families such as genetics and environment13. It was calculated both for families of pediatric CD patients and for families of pediatric UC patients. A likelihood ratio test was then used to test the statistical significance of the familial association of GM-CSF Ab levels for the ICC for both groups.

Results

Study Population

A total of 275 affected probands participated; 230 of the probands had CD and 45 had UC. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the probands are summarized in Table 119. The number of relatives tested ranged from 1–5 for CD probands, and from 1–4 for UC probands, with 1 or 2 relatives included for 83% of the CD probands and 89% of the UC probands.

Table 1.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Probands

| CD n=230 |

UC n=45 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Male | 143(62) | 22(49) |

| Age at Diagnosis | ||

| 0-<10y (A1a) | 55(24) | 13(28) |

| 10-<17y (A1b) | 138(60) | 28(63) |

| 17-40y (A2) | 37(16) | 4(9) |

| Race | ||

| African American | 51(22) | 8(18) |

| Asian | 2(1) | 1(3) |

| Caucasian | 177(77) | 36(79) |

Ages are shown as per the Paris Classification system of A1a, A1b, and A2. Data are shown as n(percentage)

Variation in Serum GM-CSF Ab Concentration and Clinical Phenotype

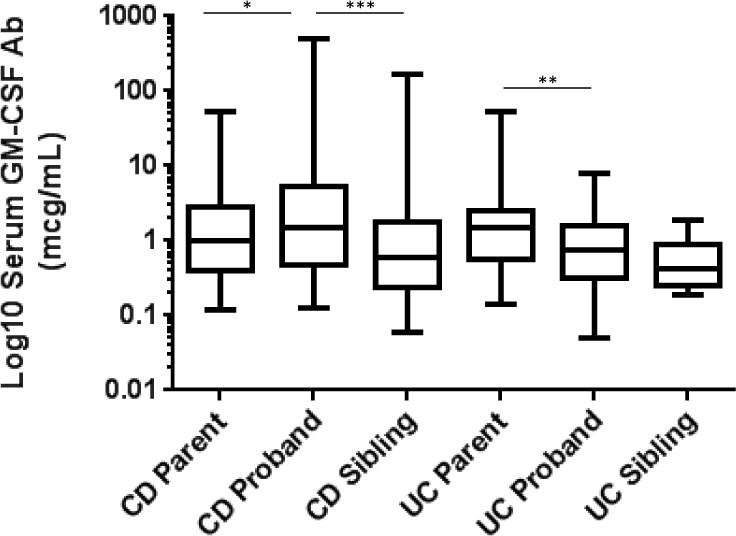

The median(IQR) serum GM-CSF Ab concentration was lower in UC probands (0.7(0.3,1.6) mcg/mL) than in CD probands (1.5(0.5,5.4) mcg/mL, Figure 1, p=0.0002 by Mann-Whitney test). Within CD families, the median(IQR) serum GM-CSF Ab concentration increased from 0.6(0.2,1.7) mcg/mL in unaffected siblings to 1(0.4,2.9) mcg/mL in unaffected parents, and 1.5(0.5,5.4) mcg/mL in CD probands (p<0.0001 by Kruskal-Wallis test). By comparison, within UC families, the median(IQR) serum GM-CSF Ab concentration did not differ between unaffected siblings (0.4(0.2,0.9) mcg/mL) and UC probands 0.7(0.3,1.6) mcg/mL, and for both was lower than in unaffected parents (1.5(0.6,2.5) mcg/mL, p=0.0022 by Kruskal-Wallis test). Amongst the CD probands, three had a mother with CD with GM-CSF Ab concentrations of 1.7, 2.1, and 26.1 mcg/mL, respectively, two had a father with UC with GM-CSF Ab concentrations of 0.98 and 2.1 mcg/mL, respectively, and three had a sibling with CD with GM-CSF Ab concentrations of 2.3, 13.2, and 49.4 mcg/mL, respectively. Amongst the UC probands, one had a mother with UC with a GM-CSF Ab concentration of 7.9 mcg/mL, and one had a father and a sibling with UC with GM-CSF Ab concentrations of 1.99 and 0.45 mcg/mL, respectively. Data regarding total serum IgG and CRP was obtained for the families enrolled at the Cincinnati site. Consistent with our prior reports, serum GM-CSF Ab concentration for the CD probands was not associated with either total serum IgG (Suppl. Fig. 1A) or CRP (Suppl. Fig 2A). While serum GM-CSF Ab concentration for the UC probands was associated with total serum IgG (r=0.62, p=0.01, Suppl. Fig. 1B), it was not associated with CRP (Suppl. Fig. 2B). Amongst the first degree relatives, serum GM-CSF Ab concentration exhibited a modest association with both total serum IgG (r=0.21, p=0.005, Suppl. Fig. 1C) and CRP (r=0.16,p=0.03, Suppl. Fig. 2C).

Figure 1. Serum GM-CSF Ab Levels in IBD Probands and Family Members.

The serum GM-CSF Ab concentration was measured by ELISA and is shown as the median (IQR) for the log10 transformed values for CD or UC parents, probands, and unaffected siblings. Differences within the CD or UC family groups were tested using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

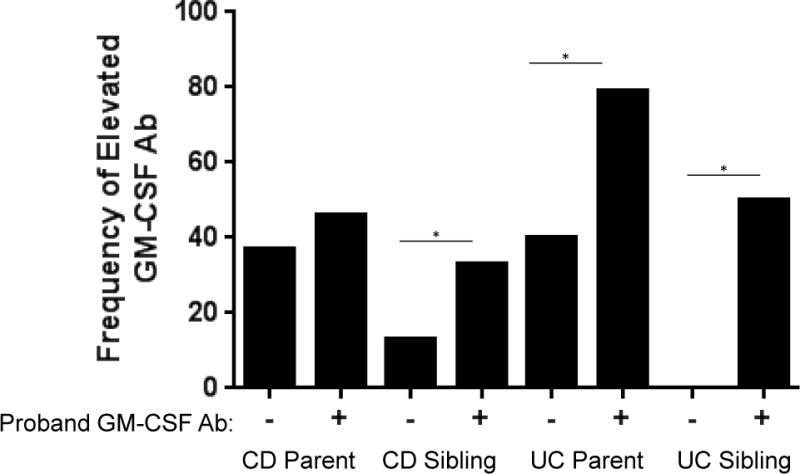

Figure 2. Frequency of Elevated GM-CSF Ab Within CD or UC Families.

The serum GM-CSF Ab concentration was measured by ELISA, with an elevated value defined as ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL. The percentage of CD or UC parents or unaffected siblings with elevated GM-CSF Ab is shown stratified by the status of the CD or UC proband. Proband GM-CSF Ab - indicates a serum value < 1.6 mcg/mL; proband GM-CSF Ab + indicates a serum value ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL. Differences between groups were tested by χ2 test. *p<0.05

The serum GM-CSF Ab concentration was ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL in 49% of the CD probands, and 24% of the UC probands. Data regarding disease location and behavior was available for the families enrolled at the Cincinnati site. As shown in Suppl. Table 1, CD probands with elevated GM-CSF Ab were less likely to exhibit inflammatory disease behavior (52% vs. 77%, p=0.006), and more likely to exhibit stricturing disease behavior (18% vs. 5%, p=0.04) than CD probands without elevated GM-CSF Ab. While the number of UC probands was too few to draw firm conclusions, there was a trend towards a higher frequency of pan-colitis (100% vs. 79%) in those with elevated GM-CSF Ab. Prior studies have demonstrated a higher frequency of elevated antimicrobial serologies within unaffected first degree relatives of CD probands with elevated antimicrobial serologies 12,13. We therefore next asked whether family members of CD or UC probands with serum GM-CSF Ab concentration ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL would be more likely to also have a serum GM-CSF Ab concentration ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL. Within CD families, the frequency of serum GM-CSF Ab concentration ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL did not differ between parents who did or did not have a child affected by CD with elevated GM-CSF Ab (46% versus 37%, respectively, Figure 2). However, the frequency of serum GM-CSF Ab concentration ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL was increased in unaffected siblings of CD probands with elevated GM-CSF Ab, compared to unaffected siblings of CD probands without elevated GM-CSF Ab (33% versus 13%, respectively, p=0.04 by χ2 test).

Within UC families, the frequency of serum GM-CSF Ab concentration ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL was increased in parents who had a child affected by UC with elevated GM-CSF Ab, compared to parents who had a child affected by UC without elevated GM-CSF Ab (79% versus 40%, respectively, p=0.01 by χ2 test). Similarly, the frequency of serum GM-CSF Ab concentration ≥ 1.6 mcg/mL was increased in unaffected siblings of UC probands with elevated GM-CSF Ab, compared to unaffected siblings of UC probands without elevated GM-CSF Ab (50% versus 0%, respectively, p=0.02 by χ2 test). Collectively, these data demonstrated that unaffected siblings of IBD probands with elevated GM-CSF Ab were more likely to also exhibit an elevated serum GM-CSF Ab concentration.

Familial association of serum GM-CSF autoantibody level within CD families

We then tested for evidence for familial association of the serum GM-CSF Ab as a continuous variable. We analyzed the GM-CSF Ab data on the log base 10 scale (or log based 10 transformed data) using a linear mixed effects model to test for familial association within families with a CD proband. We used the likelihood ratio test to test for the significance of familial association, for the 230 CD families with 634 GM-CSF Ab observations. As shown in Table 2, the log-likelihood ratio test rejected the null hypothesis of no familial association (p=0.001) in CD proband cases. For the significant familial association in the CD proband case, we obtained 95% CIs for the within family correlation: we successively used the likelihood ratio for a range of non-zero correlation values and found the lower and the upper limit of each parameter value at which the likelihood ratio test does not reject any more (p-value starts to be non-significant, i.e. p>0.05). In families of CD patients, the mean (95th CI) intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was equal to 0.153 (0.036,0.275). These results indicated that 15% of variation in the serum GM-CSF Ab level on the log base 10 scale was accounted for by factors shared within the family.

Table 2.

Model for Familial Association of Serum GM-CSF Ab Level

| Model Fit Comparison Against No Familial Association Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No familial association | Familial association among all family members | ||

| −2 log likelihood (p-value) | Intra-class correlation (ICC) coefficient (95% CI) | ||

| CD (n=230 families with 634 observations) | 1251.3 | 1237.6 (p=0.001) |

0.153 (0.036, 0.275) |

| UC (n=45 families with 116 observations) | 160.5 | 154.4 (p=0.047) |

0.270 (0.239, 0.308) |

Familial association of serum GM-CSF autoantibody level within UC families

We then performed the same analysis for the smaller number of UC families. We used the likelihood ratio test to test for the significance of familial association within 45 UC families with 116 serum GM-CSF Ab observations. As shown in Table 2, the log-likelihood ratio test rejected the null hypothesis of no familial association (p=0.047) in UC proband cases. In families of UC patients, the mean (95th CI) intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was equal to 0.27(0.24,0.31), indicating that 27% of variation in the GM-CSF Ab level was accounted for by factors shared within the family.

Familial association of serum GM-CSF autoantibody level after adjusting for total serum IgG

Finally, we used regression to adjust for the association between serum GM-CSF Ab and total serum IgG in the subset of 109 families where both values were measured. Residuals from the regression analysis correspond to the serum GM-CSF Ab level adjusted for the total IgG level. The residuals were used as the response instead and we repeated the linear mixed effects model analysis and associated likelihood ratio test for the significance of familial association. As shown in Supplemental Table 2, this analysis confirmed familial association of serum GM-CSF Ab level within both CD and UC families after adjusting for total serum IgG.

Discussion

Endogenous cytokine auto-antibodies (Ab) regulate disease activity in several infectious and auto-immune diseases 20–25. Whether variable responses to cytokine administration (GM-CSF, IL-10) or blockade (IL-17A, IFNγ, TNFα) in IBD clinical trials has been due in part to endogenous cytokine Ab is not known26–32. We discovered that a sub-set of CD patients exhibit high titers of Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) Ab3. Increased titers of GM-CSF Ab are associated with reduced GM-CSF signaling and phagocyte antimicrobial function, increased intestinal permeability, and an expansion of CCR9+ effector T cells in the affected ileum2,3,32,33. Our initial and replication studies in more than 1000 adult and pediatric CD patients have shown that elevated GM-CSF Ab are associated with higher rates of stricturing behavior and surgery3,34.

However, whether variation in serum GM-CSF Ab within CD and UC patients is due to genetic and/or environmental factors shared within families was not known. In the current study, we have for the first time defined a significant familial association for serum GM-CSF Ab levels. From 15% (CD) to 27% (UC) of the variation in the serum GM-CSF Ab level was accounted for factors shared within the families. This is comparable to the association of serum ASCA previously reported within affected CD families 9,13.

Most cytokine Ab are high affinity IgG Ab, suggesting involvement of plasma cells differentiated from cytokine-reactive B-cells in the setting of a dysregulation in T-cell tolerance1,20–25, 35, 36. Chronic cytokine stimulation may then trigger Ab production. A recent detailed analysis of epitope usage by GM-CSF Ab purified from PAP patients demonstrated that the target antigen is in fact GM-CSF, and not a molecular mimic35,36. While a genetic basis for variation in serum GM-CSF Ab has not been identified, Ab targeting type I IFN, and the Th17 cytokines IL-17A and IL-22, develop in the setting of loss-of-function mutations in the AIRE gene in APECED patients22. Current evidence supports a mechanism by which cytokine Ab production triggered by acquired factors such as antigen exposure and viral infection is strongly enhanced by impaired clonal deletion of self-reactive T cells under the AIRE gene abnormality in patients with APECED22.

It is likely that many genetic loci which influence IBD risk and/or behavior function as quantitative trait loci16,17. This may include genetic regulation of serum cytokine Ab levels. This is supported by our observation regarding an increased frequency of elevated GM-CSF Ab in parents of UC probands with elevated GM-CSF Ab, as well as unaffected siblings of CD or UC probands with elevated GM-CSF Ab. We observed a modest association between serum GM-CSF Ab concentration and both serum CRP and total IgG in first degree relatives of the IBD probands. It will be of interest in future studies to determine whether unaffected parents or siblings with elevated GM-CSF Ab exhibit increased intestinal permeability, and are more likely to later develop CD or UC. If so, cytokine Abs may provide unique insight into processes related to disease development.

Our study included a large number of CD families including mothers, fathers, and unaffected siblings, and serum GM-CSF Ab observations determined at two sites. However, limitations of our study included the relatively small number of UC families, the lack of complete information regarding disease location and behavior, and the lack of information about disease activity at the time of serum collection. In our prior reports of GM-CSF Ab in IBD, we have found that the serum concentration increases with increasing age-of-onset, small bowel location, and during active disease3,34,35. We have not identified an association with gender or duration of disease. Because of the retrospective nature of our study, we were not able to account for disease activity at the time of serum GM-CSF Ab measurement in our analysis. A future prospective study will need to be conducted to confirm the current results, which will account for disease activity, and include a larger number of UC families. Moreover, it is likely that genetic variants may regulate cytokine Ab levels, and thereby disease behavior and treatment responses, without affecting risk for the development of IBD itself. Our future studies will therefore also seek to discover and validate novel genetic loci associated with GM-CSF Ab levels in both adult and pediatric IBD patients and healthy controls, guided by the degree of family association defined in the current report.

Supplementary Material

What is Known/What is New.

What is Known

Elevated Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor auto-antibodies (GM-CSF Ab) are associated with increased intestinal permeability and stricturing behavior in Crohn’s Disease (CD).

Antibodies directed against Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ASCA), Escherichia coli (anti-OmpC), Pseudomonas fluorescens (anti-I2), and flagellin (anti-CBir1), representing responses to enteric microbiota, are serologic markers associated with different phenotypes of IBD.

These antimicrobial serologies demonstrate familial association in Crohns’s Disease.

What is New

The frequency of elevated serum GM-CSF Ab concentration was increased in unaffected siblings of both CD and UC probands with elevated GM-CSF Ab.

Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis confirmed familial association of the serum GM-CSF Ab level.

This familial association could be accounted for by either genetic or environmental factors shared within the family.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIDDK via R01DK078683 (LAD), R01DK098231 (LAD & SK), and T32 DK007727 (SSW and AT). We thank the study staff at Emory University for subject enrollment and clinical data collection, and the patients and their families for their participation.

Source of Funding. Dr. Denson has received research support from Janssen to study GM-CSF Ab. This work was supported by NIH/NIDDK via R01DK078683 (LAD), R01DK098231 (LAD & SK), and T32 DK007727 (SSW and AT).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Author Contributions

Sandra S. Wright, MD: study design, data acquisition, drafting of the work, and final approval.

Anna Trauernicht, MD: study design, data acquisition, revising of the work, and final approval.

Erin Bonkowski, BA: data acquisition, revising of the work, and final approval.

Courtney A. McCall, BS: data acquisition, revising of the work, and final approval.

Elizabeth A. Maier, BS: data acquisition, revising of the work, and final approval.

Ramona Bezold, BSN: data acquisition, revising of the work, and final approval.

Kathleen Lake, MSW: data acquisition, revising of the work, and final approval.

Claudia Chalk, BS: data acquisition, revising of the work, and final approval.

Bruce C. Trapnell, MD: study design, data interpretation, revising of the work, and final approval.

Mi-Ok Kim, PhD: study design, data analysis & interpretation, revising of the work, and final approval.

Subra Kugathasan, MD: study design, data interpretation, revising of the work, and final approval.

Lee A. Denson, MD: study design, data interpretation, revising of the work, and final approval.

References

- 1.Uchida K, et al. GM-CSF Autoantibodies and Neutrophil Dysfunction in Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:567–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nylund CM, et al. Granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies and increased intestinal permeability in Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 May;52(5):542–8. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181fe2d93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han X, Uchida K, Jurickova I, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies in murine ileitis and progressive ileal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1261–71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.046. e1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabritz J, Bonkowski E, Chalk C, et al. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor auto-antibodies and disease relapse in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1901–10. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubinsky MC, Taylor K, Targan SR, Rotter JI. Immunogenetic phenotypes in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Jun 21;12(23):3645–50. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i23.3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnott ID, et al. Sero-reactivity to microbial components in Crohn’s disease is associated with disease severity and progression, but not NOD2/CARD15 genotype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Dec;99(12):2376–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro-Santos P, Mozo L, Gutierrez C, et al. TNFalpha genotype influences development of IgA-ASCA antibodies in Crohn's disease patients with CARD15 wild type. Clin Immunol. 2006;121:305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro-Santos P, Suarez A, Mozo L, et al. Association of IL-10 and TNFalpha genotypes with ANCA appearance in ulcerative colitis. Clin Immunol. 2007;122:108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devlin SM, Yang H, Ippoliti A, et al. NOD2 variants and antibody response to microbial antigens in Crohn's disease patients and their unaffected relatives. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:576–86. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markowitz J, Kugathasan S, Dubinsky M, et al. Age of diagnosis influences serologic responses in children with Crohn's disease: a possible clue to etiology? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:714–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGovern DP, Taylor KD, Landers C, et al. MAGI2 genetic variation and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:75–83. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mei L, Targan SR, Landers CJ, et al. Familial expression of anti-Escherichia coli outer membrane porin C in relatives of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1078–85. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton CL, Yang H, Li Z, et al. Familial expression of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies in affected and unaffected relatives of patients with Crohn's disease. Gut. 2000;46:58–63. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takedatsu H, Taylor KD, Mei L, et al. Linkage of Crohn's disease-related serological phenotypes: NFKB1 haplotypes are associated with anti-CBir1 and ASCA, and show reduced NF-kappaB activation. Gut. 2009;58:60–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.156422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu JE, De Ravin SS, Uzel G, et al. High levels of Crohn's disease-associated anti-microbial antibodies are present and independent of colitis in chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Immunol. 2011;138:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregersen PK, Diamond B, Plenge RM. GWAS implicates a role for quantitative immune traits and threshold effects in risk for human autoimmune disorders. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:538–43. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–24. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uchida K, Nakata K, Suzuki T, et al. Granulocyte/macrophage-colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies and myeloid cell immune functions in healthy subjects. Blood. 2009;113:2547–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-155689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine A, et al. Pediatric Modification of the Montreal Classification for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Paris Classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Jun;17(6):1314–21. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, et al. Adult-onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:725–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burbelo PD, Browne SK, Sampaio EP, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies are associated with opportunistic infection in patients with thymic neoplasia. Blood. 2010;116:4848–58. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karner J, Meager A, Laan M, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies suggest pathogenetic links with autoimmune regulator deficiency in humans and mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;171:263–72. doi: 10.1111/cei.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Svenson M, Hansen MB, Ross C, et al. Antibody to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is a dominant anti-cytokine activity in human IgG preparations. Blood. 1998;91:2054–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe M, Uchida K, Nakagaki K, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies are ubiquitous in healthy individuals. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2017–21. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe M, Uchida K, Nakagaki K, et al. High avidity cytokine autoantibodies in health and disease: pathogenesis and mechanisms. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebert EC, Das KM, Mehta V, et al. Non-response to infliximab may be due to innate neutralizing anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha antibodies. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;154:325–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03773.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitzky S, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn's disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2012;61:1693–700. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korzenik JR, Dieckgraefe BK, Valentine JF, et al. Sargramostim for active Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2193–201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reinisch W, de Villiers W, Bene L, et al. Fontolizumab in moderate to severe Crohn's disease: a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:233–42. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schreiber S, Fedorak RN, Nielsen OH, et al. Safety and efficacy of recombinant human interleukin 10 in chronic active Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s Disease IL-10 Cooperative Study Group. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1461–72. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jurickova I, Collins MH, Chalk C, et al. Paediatric Crohn disease patients with stricturing behaviour exhibit ileal granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) autoantibody production and reduced neutrophil bacterial killing and GM-CSF bioactivity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;172:455–65. doi: 10.1111/cei.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samson CM, Jurickova I, Molden E, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor blockade promotes ccr9(+) lymphocyte expansion in Nod2 deficient mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2443–55. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gathungu G, Kim MO, Ferguson JP, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies: a marker of aggressive Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1671–80. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281f506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Thomson CA, Allan LL, et al. Characterization of pathogenic human monoclonal autoantibodies against GM-CSF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7832–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216011110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blech M, Seeliger D, Kistler B, et al. Molecular structure of human GM-CSF in complex with a disease-associated anti-human GM-CSF autoantibody and its potential biological implications. Biochem J. 2012;447:205–15. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.