Abstract

Infantile fibrosarcoma usually presents as a rapidly growing mass on the extremities or trunk. We describe spontaneous regression in a 5 month old female infant with biopsy proven, molecularly confirmed, right leg infantile fibrosarcoma currently at 26 months of age with no signs of local recurrence. Previously reported cases of spontaneous regression are reviewed, suggesting a benign clinical course in some cases. Although evidence for spontaneous regression is anecdotal in this rare tumor type, physicians should weigh the risks and benefits of surgery and chemotherapy against watchful waiting.

Keywords: spontaneous regression, infantile fibrosarcoma, surgery

INTRODUCTION

Infantile fibrosarcoma (IFS) is a rare type of non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma that affects children primarily before the age of 2; 60% of the cases are diagnosed before the age of 3 months; 30–50% are present already at birth and some cases are diagnosed in utero.(1) The estimated incidence is five new cases per million infants. (1) In contrast to fibrosarcoma in adults, IFS is a low-grade tumor and displays a benign clinical behavior. The natural history is usually that of a rapidly growing mass in the deep soft tissues of the extremities or trunk, while distant metastases and lymph node involvement are rare. (2–4) Histopathologically, the tumor is characterized by densely cellular spindle cells with a high proliferative rate and areas of necrosis arranged in intersecting bundles with a herringbone pattern, but some tumors may have a hemangiopericytoma-like pattern of growth. Tumor cells have a fibroblastic and myofibroblastic ultrastructure and a non-specific immunophenotype with variable positivity for desmin and actin. IFS is characterized by the recurrent translocation t(12;15)(p13;q25) with the transcript ETV6-NTRK3(5, 6) and significant receptor tyrosine kinase activation (PI3-Akt, MAPK and SRC activation) has been reported. (7)

Current management of IFS has evolved to include initial biopsy and chemotherapy (8), with delayed conservative resection planned after tumor shrinkage. Occasionally, patients with unresectable tumors may undergo spontaneous regression with chemotherapy alone, sparing patients from surgery. The need for adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection is less clear, even when the tumor is incompletely resected: the European soft tissue sarcoma group guidelines recommend only close surveillance for initially resected patients (9). Given the young age of these patients, radiotherapy is of limited value as bone growth in limbs would be severely compromised. ETV6-NTRK3 transcript may represent a potential therapeutic target, but; is not totally specific to IFS and has been identified in other tumors including mammillary carcinoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia and high grade gliomas (10) Herein, we describe a 5-month-old infant with biopsy proven, molecularly confirmed, right leg IFS which underwent gradual spontaneous regression; she is thriving and well at 26 months of age. A review of IFS relevant literature is provided.

CASE REPORT

A 5-month-old previously healthy infant presented with a lump on the right ankle, which was progressively increasing in size for 1 month but was not painful. Physical exam demonstrated a firm non-tender mass in the anterolateral aspect of the right ankle, extending from the right lateral ankle to mid upper third of the leg, 4 × 4 cm in size. She subsequently underwent an MRI of the right ankle, which demonstrated the presence of a well-circumscribed intramuscular mass with well-defined peripheral margins measuring 2.3 cm × 1.9 cm × 5.6 cm in the transverse, antero-posterior, and craniocaudad dimensions respectively. The mass involved the extensor digitorum longus and external hallucis longus muscles (anterior compartment of the leg) and was causing posterior bowing of the interosseus membrane and scalloping of fibula. The mass appeared isointense on T1 imaging, hyperintense on T2 imaging and was noted to be heterogeneously enhancing with restricted diffusion (figure 1). The differential diagnosis included IFS, rhabdomyosarcoma and hemangioma. A core needle biopsy of the mass was performed. Pathology showed a spindle cell neoplasm with slightly irregular ovoid to epithelioid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, frequent intranuclear vacuoles, and rare nucleoli with mild cellular pleomorphism (figure 2). These cells were present in a variably fibrous stroma, arranged in fascicles and focally showed a hemangiopericytoma-like growth pattern with irregular, ectatic blood vessels. Immunohistochemical studies for SMA, desmin, myogenin, ALK, EMA, and S-100 were negative; and the Ki-67 proliferation index was greater than 70%. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) studies showed rearrangement of the ETV6 gene. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of IFS. Surgical resection was rejected because it would result in severe loss of function of the leg and an initial decision was made to carefully monitor the patient with physical exam and MRI without any intervention. Four months following diagnosis, repeat MRI showed that the tumor had increased in size to 3.1 × 2.8 × 8.2 cm with associated fibular bowing and sclerotic changes noted in both the tibia and fibula. We recommended initiation of systemic chemotherapy followed by resection. However, upon closer review of history obtained from the parents, it was deemed that the enlargement of the mass took place between the baseline MRI and the biopsy and the mass appeared to be decreasing in size following the biopsy. Parents were reassured because the patient was cruising, had good mobility and was bearing weight on the right foot without apparent pain. Ultimately, it was decided to repeat MRI 6 weeks later, which showed that the tumor was stable in size and now appeared more cystic and necrotic. The tumor started to shrink thereafter and by the age of 24 months, was impalpable, though the right leg remained mildly hypertrophied compared with the left. At the age of 2 years, the child is well with no signs of disease and normal function in the affected limb (figure 1).

Figure 1.

MRI scans at presentation (A) axial T1 image which demonstrates a well-circumscribed, heterogeneously enhancing, intramuscular mass with distinct peripheral margins measuring 3.1 cm × 2.8 cm × 8.2 cm in the transverse, antero-posterior, and craniocaudad dimensions respectively. The mass involves the extensor digitorum longus and external hallucis longus muscles (anterior compartment of the leg) and is causing posterior bowing of the interosseus membrane and scalloping of the fibula. (B) Sagittal T1 image demonstrates that the tumor extends inferiorly to the level of the anterior ankle joint without definite intra articular extension. MRI scans18 months post initial presentation; (C) Axial T1 and (D) sagittal T2 images demonstrate interval decrease in size of fibrosarcoma within the anterior compartment of the distal leg measuring 1.5 × 1.2 × 6.8 cm. All images are fat suppressed post gadolinium contrast.

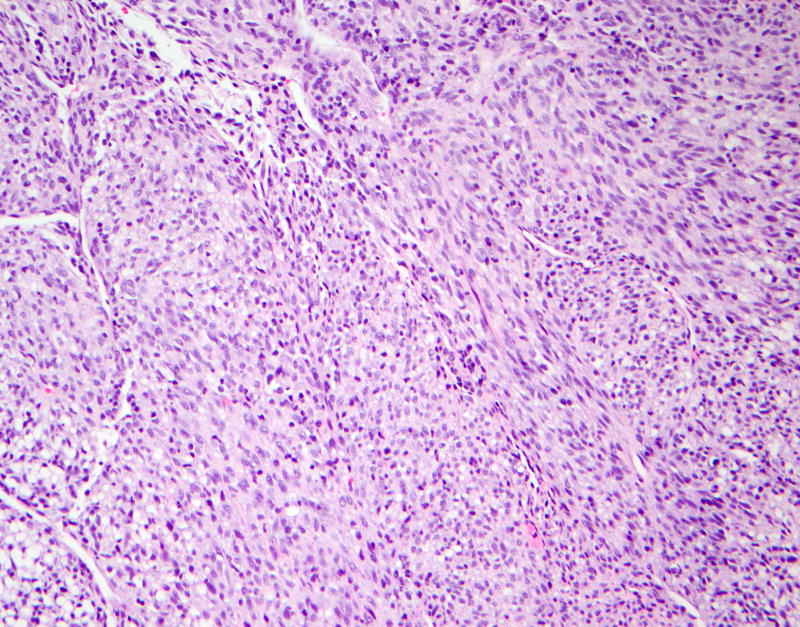

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin (20× magnification) The lesion consists of spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with focal irregular hemangiopericytoma-like vasculature.

DISCUSSION

Our case report confirms and expands on the currently available literature on spontaneous regression of IFS. The current patient is only the fourth case reported. The clinical characteristics of the three previously reported cases are summarized and compared to our patient in table 1. (11–13) The pathological definition of IFS remains debatable, and diagnosis should not be based solely on either the patient’s age or the tumor’s clinical presentation and histological features, but on its molecular characteristics. In fact, our patient represents only the second such reported case, wherein, a molecularly confirmed IFS was noted to regress spontaneously.

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical characteristics and outcomes for patients with spontaneous regression of infantile fibrosarcoma.

| Patient number 1 (current case) |

Patient number 2 |

Patient number 3 |

Patient number 4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis/sex | 5 months/F | 5 months/F | Neonate/M | 6 weeks/M |

| ETV6-NTRK3 transcript | Yes | Not tested | Not tested | Yes |

| Site of primary tumor | Right ankle | Left thigh | Left elbow | Shoulder |

| Status | Alive with tumor 80% decreased from diagnosis | Alive, Complete regression | Alive, complete regression | Alive with tumor decreased from diagnosis |

| Time from diagnosis to last follow up | 21 months | 18 months | 4 years | 3 years |

| Reference | current case | 12 | 13 | 14 |

Regression of IFS following partial resection was previously reported in a series of 5 patients, wherein complete regression was maintained at a median of 6 years.. Histopathological analysis revealed a significantly lower proliferative index (MIB-1 staining) coupled with enhanced apoptosis in all pediatric cases compared to adult fibrosarcoma, which may account for the benign clinical behavior of IFS.(14) More recently, an additional case in which regression followed partial tumor resection was reported. With reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis, ETV6-NTRK3 fusion transcripts were detected in the tumor sample at initial diagnosis (3 months of age), but not from the remnant tumor at 4 years of age. These genetic and histological changes suggest that the IFS either completely disappeared by apoptosis or showed mature transformation to hemangiomatous tissue over time.(15)

Common factors in these cases are difficult to ascertain given the limited number. The spontaneous regression (noting that there is still some residual change and we have not re-biopsied) observed in our patient, coupled with these previously reported patients suggests that, at least in some cases (i.e. patients <6 months with a nonresectable primary in a non-threatening situation), a more benign clinical course is possible. Anecdotal case reports do not invalidate the current treatment strategy, but treatment of patients with IFS should weigh the risks of therapy against the risks of watchful waiting, since spontaneous regression of the tumor is possible, particularly in patients diagnosed with IFS during the first 6 months of life. Given the rarity of these tumors, multi-institutional and international collaborations are required to further define the natural history of IFS and optimize multimodal therapy approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Joe Olechnowicz for editorial assistance.

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Abbreviations

- IFS

Infantile Fibrosarcoma

- FISH

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MIB-1

Monoclonal antibody to determine proliferation index of tumors

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription Polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ries L, Smith M, Gurney J, et al. Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents : United States SEER program 1975–1995. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. NIH Pub. No. 99-4649; Bethesda, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari A, Orbach D, Sultan I, et al. Neonatal soft tissue sarcomas. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17:231–8. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brisse HJ, Orbach D, Klijanienko J. Soft tissue tumours: imaging strategy. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1019–28. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1592-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan AC, Chamlin SL, Liang MG, et al. Congenital infantile fibrosarcoma: a masquerader of ulcerated hemangioma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:330–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knezevich SR, Garnett MJ, Pysher TJ, et al. ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusions and trisomy 11 establish a histogenetic link between mesoblastic nephroma and congenital fibrosarcoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5046–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourgeois JM, Knezevich SR, Mathers JA, et al. Molecular detection of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion differentiates congenital fibrosarcoma from other childhood spindle cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:937–46. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadd S, Beezhold P, Jennings L, et al. Mediators of receptor tyrosine kinase activation in infantile fibrosarcoma: a Children's Oncology Group study. J Pathol. 2012;228:119–30. doi: 10.1002/path.4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orbach D, Rey A, Cecchetto G, et al. Infantile fibrosarcoma: management based on the European experience. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:318–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari A, Casanova M. New concepts for the treatment of pediatric nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5:307–18. doi: 10.1586/14737140.5.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagasubramanian R, Wei J, Gordon P, et al. Infantile Fibrosarcoma With NTRK3-ETV6 Fusion Successfully Treated With the Tropomyosin-Related Kinase Inhibitor LOXO-101. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1468–70. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobson L, Dickey LB. Spontaneous regression of malignant tumors; report of a twelve-year spontaneous complete regression of an extensive fibrosarcoma, with speculations about regression and dormancy. Am J Surg. 1956;92:162–73. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(56)80056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madden NP, Spicer RD, Allibone EB, et al. Spontaneous regression of neonatal fibrosarcoma. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1992;18:S72–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orbach D, Brennan B, De Paoli A, et al. Conservative strategy in infantile fibrosarcoma is possible: The European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group experience. Eur J Cancer. 2016;57:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kihara S, Nehlsen-Cannarella N, Kirsch WM, et al. A comparative study of apoptosis and cell proliferation in infantile and adult fibrosarcomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106:493–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/106.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miura K, Han G, Sano M, et al. Regression of congenital fibrosarcoma to hemangiomatous remnant with histological and genetic findings. Pathol Int. 2002;52:612–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2002.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]