Abstract

BACKGROUND

Addressing record high rates of Chlamydia trachomatis (Ct) incidence in the United States (U.S.) requires the utilization of effective strategies, such as expedited partner therapy (EPT), to reduce reinfection and further transmission. EPT, which can be given as a prescription or medication, is a strategy to treat the sexual partners of index patients diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection (STI) without prior medical evaluation of the partners.

OBJECTIVE

There are multiple steps in the prescription-EPT cascade and we sought to identify pharmacy-level barriers to implementing prescription-EPT for Ct treatment.

STUDY DESIGN

We used spatial analysis and ArcGIS, a geographic information system, to map and assess geospatial access to pharmacies within Baltimore, Maryland neighborhoods with the highest rates of Ct (1180.25-4255.31 per 100,000 persons). EPT knowledge and practices were collected via a telephone survey of pharmacists employed at retail pharmacies located in these same neighborhoods. Cost of antibiotic medication in U.S. Dollars (USD) was collected.

RESULTS

Census tracts with the highest Ct incidence rates had lower median pharmacy density than other census tracts (26.9 per 100,000 v. 31.4 per 100,000, P<.001). We identified 25 pharmacy deserts. Areas defined as pharmacy deserts had larger proportions of Black and Hispanic or Latino populations compared to non-Hispanic whites (93.1% v. 6.3%, P<.001) and trended toward higher median Ct incidence rates (1170.0 per 100,000 v. 1094.5 per 100,000, P=.110) than non-pharmacy desert areas. Of the 52 pharmacies identified, 96% (50/52) responded to our survey. Less than a fifth of pharmacists (18%, 9/50) were aware of EPT for Ct. Most pharmacists (59%, 27/46) confirmed they would fill an EPT prescription. The cost of a single dose of azithromycin (1 gram) ranged from 5-39.99 USD (median, 30 USD).

CONCLUSION

Limited geographic access to pharmacies, lack of pharmacist awareness of EPT, and wide variation in EPT medication cost are potential barriers to implementing prescription-EPT. Although most Baltimore pharmacists were unaware of EPT, they were generally receptive to learning about and filling EPT prescriptions. This finding suggests the need for wide dissemination of educational material targeted to pharmacists. In areas with limited geographic access to pharmacies, EPT strategies that do not depend on partners physically accessing a pharmacy merit consideration.

Keywords: Expedited partner therapy, EPT, STI, STD, Baltimore, pharmacy access, pharmacy desert, Chlamydia, partner therapy, sexually transmitted infection, sexually transmitted disease

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydia trachomatis (Ct) is the most common notifiable sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States (U.S.) with over 1.5 million new Ct infections reported annually. The rate has increased every year since 2013, and the most recently reported rate of 497.3 cases per 100,000 persons is the highest ever reported to the CDC in U.S. history.1 Untreated Ct infection can increase a woman’s risk of acquiring HIV and can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which is a major cause of infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain.2,3 Furthermore, the odds of PID are 4 to 6-fold higher after two (odds ratio [OR] 4.0, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.6-9.9) and three or more (OR 6.4, 95% CI 2.2-18.4) Ct infections compared to the initial infection; and the odds of ectopic pregnancy are 2 to 4-fold higher after two (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.3 – 3.4) and three or more (OR 4.5, 95% CI 1.8-5.3) Ct infections.4 Although re-infection can be prevented by prompt treatment of both patients and their partners, twenty percent of treated female patients are re-infected with Ct within a year after treatment.5 Despite the record rates of Ct incidence in the U.S. and significant reproductive morbidity, state and local funding for STI prevention has dropped, leading to clinic closures, fewer services, and less access to care.1

Addressing rising Ct incidence rates in an environment of fewer public health resources requires a multi-pronged approach, including more effective treatment strategies like expedited partner therapy (EPT). EPT is a treatment option that allows health care providers to treat the sexual partners of index patients diagnosed with an STI without medically evaluating the partners. It has been shown to decrease Ct re-infection among index patients and increase treatment of sex partners.6 Additionally, randomized control trials have reported that EPT reduces Ct re-infection more than unassisted patient referrals.7,8

EPT can be given as medication or in the form of a physical prescription.9 Although more common, prescription-EPT involves numerous steps to treat the sexual partner. A continuum of seven steps for complete implementation of prescription-EPT has been proposed by Schillinger et al. which includes: 1) index patient treated by EPT-utilizing provider; 2) index patient offered prescription-EPT by provider; 3) index patient accepts prescription-EPT; 4) index patient gives the physical prescription-EPT to sexual partner(s); 5) sexual partner(s) receives and fills the prescription at a pharmacy; 6) sexual partner(s) pays for the medication; and 7) sexual partner(s) ingests the medication.10 The provider does not establish a relationship with the partner. This prescription-EPT continuum highlights the pivotal role of pharmacies and pharmacists in successful EPT utilization. Physical access to pharmacies is necessary. In addition, many states that have legalized EPT do not require the provider to write the partner’s name on the prescription and instead accept “EPT” on the prescription.11 Thus, pharmacists must be knowledgeable about EPT. However, there is a paucity of literature on pharmacy-level barriers to EPT. The purpose of this study was to identify barriers along the prescription-EPT continuum. Specifically, our primary objective was to determine if there was a relationship between pharmacy access and Ct incidence. Secondary objectives included use of geographic information systems (GIS) to organize, visualize, and analyze geographic pharmacy data, and an assessment of pharmacists’ knowledge and practices of filling EPT prescriptions for Ct infections. We hypothesized that low pharmacy access and lack of awareness of EPT among pharmacists are barriers to effective implementation of prescription-EPT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

GIS Mapping and Spatial Analyses

Lists of licensed retail pharmacies were obtained from Evergreen Health’s Maryland Pharmacy Directory and the Maryland State Board of Pharmacy.12,13 Pharmacy access was measured two ways – pharmacy density and pharmacy desert.

First, pharmacy density was assessed both qualitatively and quantitatively. We used ArcGIS 10.4.1, a geographic information system, to map the distribution of Baltimore, Maryland pharmacies located within the highest Ct incidence areas (1180.25-4255.31 per 100,000 persons), which were up to 9-fold higher than the national average (497.3 per 100,000).14,15 We assigned latitude and longitude coordinates to pharmacy addresses using the ArcGIS Online Geocoding Service. We created a heat map of Baltimore pharmacies using kernel density estimation to qualitatively compare pharmacy density. Then, we calculated the number of pharmacies per 100,000 persons in each zip code area to quantitatively compare pharmacy density.

Second, we identified pharmacy deserts. We calculated the percentage of each census tract that was within walking distance (within .5 miles) to a pharmacy using tabulate intersection in ArcGIS. We followed the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Access Research Atlas definition of a pharmacy desert based on the following three conditions: 1) 33% or more of a census tract was not within walking distance to a pharmacy; 2) had low vehicle access, which was defined as more than 100 households without a vehicle; and 3) was considered low income, which was defined as a median income less than 80% of Baltimore’s median income or if more than 20% of households had an income under the Federal Poverty Level.16 All 200 Baltimore City census tracts, not just areas with high Ct incidence, were included in the spatial analysis. Census tract demographic and economic data from the 2011-2015 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau were used.17

Telephone interviews

EPT became legally permissible on June 1, 2015 for Ct infection in Maryland, and regulations addressing the implementation of EPT for healthcare providers were adopted on March 28, 2016.18-19 We conducted a telephone interview of retail pharmacies located within Baltimore zip codes with the highest Ct incidence from March through June 2017. Some zip code areas extended past the geographic boundary of the city, and pharmacies located within these areas were retained.

The telephone interview questions were based on surveys in the literature regarding prescription sales practices in retail pharmacies.20 The interviews were designed to be answered by any pharmacist, but we requested to speak to the supervising pharmacist. We attempted to contact pharmacies up to three times. The study was deemed exempt by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine institutional review board.

Data analysis

The highest quartile of Ct incidence (1180.25-4255.31 per 100,000 persons) was used as the cut-off to create a high Ct incidence variable, which was applied to each census tract. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to assess the relationship between pharmacy density and Ct incidence, and to determine if there were differences in demographics between pharmacy deserts and non-pharmacy deserts. Logistic regression was used to describe the relationship between minority populations (i.e. non-Hispanic black and Hispanic or Latino), and pharmacy desert. We divided census tracts into three groups: 1) tracts that were mostly (more than 2/3) comprised of minorities; 2) tracts that had similar populations (between 1/3 and 2/3) of non-Hispanic whites and minorities; and 3) tracts that were mostly non-Hispanic white (less than 1/3 minorities). Results were reported as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

We assessed whether income was associated with pharmacy access using both measures of access – density and desert. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Wilcoxon rank sum were used to determine if there was an association between median income and pharmacy density and pharmacy desert (without income criterion), respectively.

Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to measure association between medication cost and census tract characteristic (absolute Ct incidence rate, income, and pharmacy density).

We calculated response frequencies for all survey questions to determine the statistical distribution of pharmacist responses. Pearson chi-square or Fisher exact tests were conducted to examine differences in EPT awareness by pharmacy characteristics. Statistical significance was determined a priori at two-sided P<.05. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (version 9.4).

RESULTS

Pharmacy access

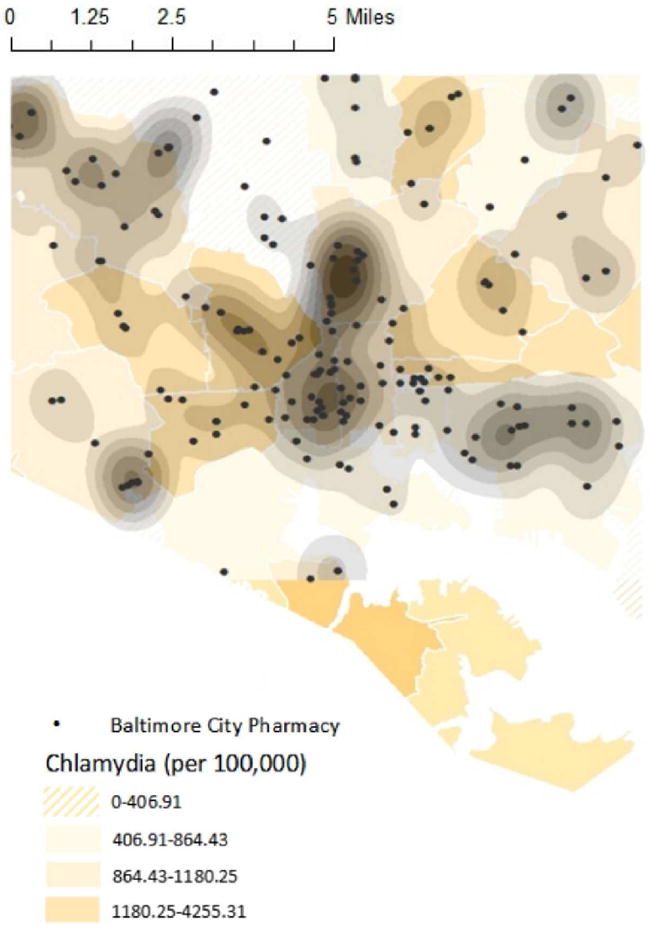

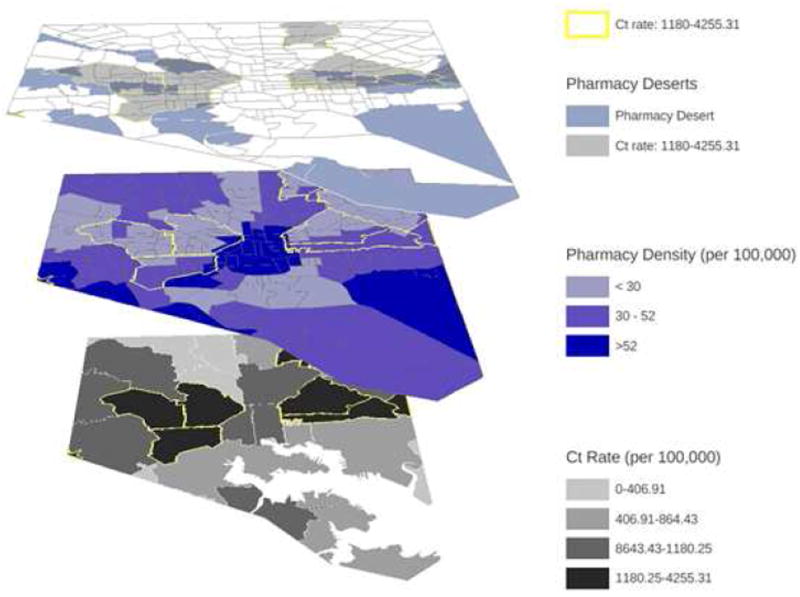

High Ct incidence census tracts had a lower median pharmacy density than other census tracts (26.9 per 100,000 v. 31.4 per 100,000, P<.001), which is demonstrated in the heat map (Figure 1). These high Ct incidence tracts were mostly inhabited by minorities compared to non-Hispanic whites (93.7% v. 6.3%, P<.001). Around a third of Baltimore (33.9%) was not within walking distance to a pharmacy, and 12.5% of census tracts (25/200) were considered pharmacy deserts (Figure 2). These pharmacy deserts had a larger percentage of minorities compared to non-Hispanic whites (93.1% v. 6.9%, P=.021). The median Ct incidence rate for pharmacy deserts trended higher compared to non-pharmacy deserts (1170.0 per 100,000 v. 1094.5 per 100,000, P=.110) but was not statistically significant. Census tracts that were mostly comprised of minorities had a 2-fold higher odds of being a pharmacy desert (OR 2.2, 95% CI:.61-7.87) compared to census tracts that were mostly non-Hispanic white. Census tracts that had similar proportions of minorities and non-Hispanic whites had a 60% higher odds of being a pharmacy desert (OR 1.6, 95% CI:.33-7.60) compared to census tracts that were mostly non-Hispanic whites.

Figure 1. Kernel Density of Pharmacies in Baltimore City.

Geospatial access to pharmacies depicted by kernel density of pharmacies in Baltimore City

Figure 2. Pharmacy Access in Baltimore City.

Geospatial access to pharmacies depicted by top graph: pharmacy deserts with areas with the highest Ct incidence rate denoted, middle graph: pharmacy density per 100,000, and bottom graph: Ct rate per zip code. Some areas in the bottom graphic look different from other graphics as the zip code shapefiles did not include the body of water like census tract shapefiles.

Median income was similar between census tracts with low pharmacy access defined either using density (rs= .007, P=.925) or desert ([without income criterion], 38,445 U.S. Dollars [USD] v. 38,864 USD, P=.651).

Telephone survey

Five pharmacies from the 57 pharmacies identified in zip code areas with high Ct incidence were excluded from the telephone interview because they were no longer in business or located within an institution not open to the public such as a nursing facility. A total of 52 pharmacies were contacted, and 96% (50/52) responded to our survey. The survey lasted a median of 7 minutes (range: 3-25 minutes).

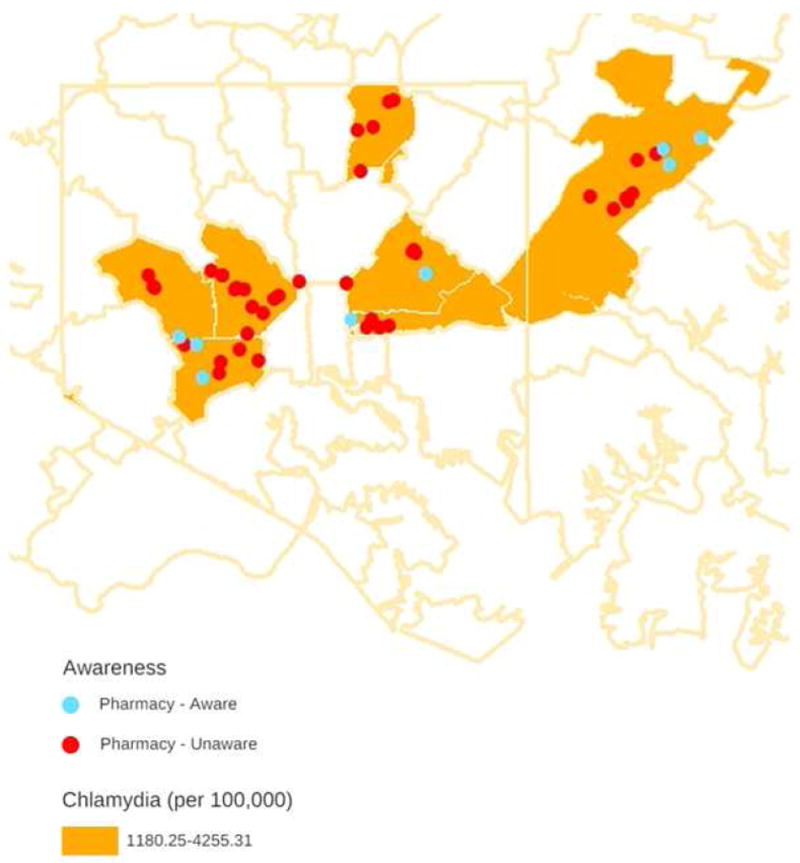

Most pharmacists (70%, 35/50) were supervisors practicing in chain pharmacies (52%, 26/50). Chain pharmacies were defined as pharmacies located in corporate drug stores, grocery stores, medical clinics, and other institutions. Less than a fifth of pharmacists (18%, 9/50, Figure 3) were aware of EPT as a treatment option, and 12% (6/50) knew EPT was legal in Maryland. Only three (6%, 3/50) pharmacists reported having received an EPT prescription at their current pharmacy, and they had received only one. The majority of pharmacists (84.1%, 37/44) reported that the age of the partner (e.g. 14 years) would not affect their decision to fill an EPT prescription and most (74.5%, 35/47) did not require identification to fill the prescription. The median cost of a single dose of azithromycin (one gram) for partners paying without insurance was 30 USD (range 5-39.99 USD). There was no association between cost of azithromycin and Ct incidence rate (rs=.122, P=.600), median income (rs=.143, P=.537), or pharmacy density (rs=.150, P=.517). Over 58% (27/46) of pharmacists confirmed they would fill an EPT prescription, and an additional 17.4% (8/46) said they would as long as it was permitted by their manager. Most pharmacists (81.6%, 40/49) were interested in receiving additional educational information, and 72.7% (32/44) of them agreed to share the material with their staff. There was no significant difference in EPT knowledge between pharmacists practicing in chain pharmacies and pharmacists practicing in independent pharmacies (23.1% v. 12.5%, P=.467). Independent pharmacies were more likely to report that they required identification to fill a prescription than chain pharmacies (33.8% v. 4.17%, P=.005). There was no significant difference in the knowledge of EPT between supervising pharmacists and non-supervising pharmacists (14.3% v. 26.7%, P=.432).

Figure 3. Distribution of Baltimore Pharmacies in High Chlamydia Incidence Areas.

Geospatial distribution of Baltimore pharmacies in high Ct incidence areas (1180.25-4255.31) listed by the Maryland State Board of Pharmacy depicting pharmacist awareness of EPT

COMMENT

Our analysis identifies geographic pharmacy access, EPT awareness, and cost as potential barriers in the prescription-EPT continuum. Limited geographic access to pharmacies may prevent effective utilization of EPT. Areas in Baltimore with the highest Ct incidence rates have the potential to benefit the most from EPT, which helps decrease re-infection and further transmission. However, these areas have significantly lower pharmacy density, leading to possible difficulties in accessing medication or filling EPT prescriptions for those most in need of treatment. The heat map depicts a hot spot of pharmacies concentrated in the center of Baltimore, which is an area that does not have the highest Ct rates. Notably, the areas with the highest rates of Ct infection surround the periphery of the hot spot and they have a much lower pharmacy density. Fewer pharmacies may translate to fewer pharmacists willing to fill the prescription or fewer options for affordable medication.

Patients living in pharmacy deserts may experience greater difficulty in accessing treatment. We expected areas defined as pharmacy deserts to have higher Ct rates, as persons living in that area may find it difficult to access prompt treatment and avoid infecting new partners. The association between pharmacy deserts and high Ct incidence rate only trended towards significance. We also found that pharmacy deserts were associated with increased Black and Hispanic or Latino populations, but was not associated with income. Additionally, the larger the minority population in a census tract, the more likely the census tract was a pharmacy desert. This conclusion is consistent with Qato et al, which found that pharmacy deserts are more prevalent in predominantly minority neighborhoods.21 This association is concerning because Black and Hispanic or Latino populations are disproportionately affected by Ct, which is the most common notifiable STI targeted by EPT.22 Inadequate pharmacy access may impede treatment of infections, potentially maintaining high STI prevalence and increasing the likelihood of further transmission in these communities.

Lack of pharmacist awareness may also pose a barrier to implementation of EPT. Passage of legislation is only the first step in using EPT for STI reduction,23 as clinicians and pharmacists must then implement EPT. Less than a fifth of pharmacists in Baltimore were aware of EPT as a treatment option for sexual partners and only 12% knew EPT was legal in Maryland. This finding is consistent with those of Reid et al. who also found low levels of knowledge and familiarity with EPT law and infrequent receipt of EPT prescriptions among NYC pharmacists two years after regulations were adopted. Maryland’s recent adoption in 2015 may be one of the contributing factors to the lack of knowledge among pharmacists regarding EPT, and time alone might increase awareness. Despite their low level of awareness of EPT, most pharmacists were interested in learning more about EPT, willing to share information about EPT with other pharmacists, and confirmed that they would fill an EPT prescription. This illustrates the importance of disseminating educational material related to EPT. While uncommon, some pharmacists reported identification card and age requirements for partners trying to fill a prescription. While identification card and age requirements may align with a pharmacy’s policy for other medications such as opioid analgesics, there are no requirements under Maryland law for prescription-EPT, emphasizing the need for pharmacist-specific educational materials to dispel misconceptions.24

Cost can also deter partners without insurance or not willing to use their insurance from accessing EPT. In 2016, 6.0% of Maryland’s population was without insurance, and 28.1 million people or 8.8% of the population nationally were without health insurance.25,26 The proportion of uninsured minority populations in Maryland was even higher at 23.6%, which is an important finding given the higher STI burden in minority populations. In addition, partners may not use their health insurance to pay for STI treatment for confidentiality reasons.27 We found a wide range in cost for one dose of azithromycin (5-39.99 USD). With a relatively high median cost of 30 USD, azithromycin may be unaffordable as five out of the seven zip code areas with high Ct incidence rates are low income neighborhoods. Uninsured partners that attempt to fill an EPT prescription in a higher charging pharmacy might decide against paying for and receiving the treatment. Without the option of other nearby pharmacies, a partner may decide to forgo the treatment altogether.

Our study has inherent limitations that should be considered. Self-reported data from the supervising pharmacist or pharmacist on shift may be affected by recall bias and may differ from the experiences of other pharmacists at that location. These findings may not be generalizable in pharmacies outside of a high STI burden area. Medication costs are for sexual partners without insurance or those who choose not to use their insurance, as we could not account for the cost of medication co-pays, since differing insurance plans may have different co-pays. Ct incidence rate in Baltimore was only available for each zip code area, so zip code data was matched with corresponding census tract. This assignment of census tract to zip code area followed geographic relationships outlined by the U.S. Census Bureau.28 We similarly reassigned data for pharmacy density per zip code area to the corresponding census tract. Census tracts covered too little area to obtain meaningful data related to pharmacy density. We consider our finding a possible underestimate because the census tract shapefiles include bodies of water. Areas that included waterways but were also considered pharmacy deserts had lower Ct rates and could have under-estimated the association between pharmacy deserts and Ct rate.

The current study has clinical implications with respect to identifying barriers in large urban areas similar to Baltimore that need to be addressed in order for EPT to prevent reproductive morbidity. Our findings suggest the need for wide dissemination of educational material targeted to pharmacists. Variance in cost of EPT medication for uninsured patients highlights a potential need for cross collaboration between institutions, health insurance companies, and the health department to help reduce the cost of EPT. In areas with limited geographic access to pharmacies, programs that do not depend on partners physically accessing a pharmacy merit consideration like medication-EPT that includes clinic dispensing or mail delivery of antibiotics should be explored. In addition, as pharmacists report receiving few EPT prescriptions, unfamiliarity with EPT may extend to clinicians who could prescribe EPT. Additional educational materials for those clinicians may also improve the utilization of EPT.

CONCLUSION

Limited geographic access to pharmacies, lack of pharmacist awareness of EPT, and wide variation of cost of EPT medication are barriers to prescription-EPT. Lack of awareness can be addressed by additional training for pharmacists, who generally are willing to accept EPT prescriptions after receiving information. Areas with more complicated barriers to surmount, such as low access to pharmacies and few options for affordable medication, warrant consideration of approaches that do not depend on existing pharmacy infrastructure, such as medication-EPT that includes clinic dispensing or mail delivery.

Summary.

A study of pharmacies in Baltimore, Maryland found barriers to prescription-EPT, including limited geographic access to pharmacies, pharmacist unawareness, and high medication cost.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Baltimore City Department of Health for providing data on Ct incidence rates and pharmacists who reserved time to participate in our telephone interview.

Research Support: None

Footnotes

Paper presentation: Presented at the 2017 IDSOG Annual Meeting, Park City, Utah

Disclaimers: None

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance Report. [September 27, 2017];2016 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats165/default.htm.

- 2.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75(1):3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2016 National Profile - Chlamydia. [September 27, 2017]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats165/chlamydia.htm.

- 4.Hillis SD, Owens LM, Marchbanks PA, Amsterdam LE, Mac Kenzie WR. Recurrent chlamydial infections increase the risks of hospitalization for ectopic pregnancy and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(1):103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)80020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;26(8):478–489. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a2a933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kissinger P, Hogben M. Expedited partner treatment for sexually transmitted infections: an update. Current infectious disease reports. 2011;13(2):188–195. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schillinger JA, Kissinger P, Calvet H, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment with azithromycin to prevent repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women: a randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(1):49–56. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiely F, Hayes K, Thomas KK, et al. Expedited partner therapy: a robust intervention. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(10):602–607. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e1a296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliver A, Rogers M, Schillinger JA. The impact of prescriptions on sex partner treatment using expedited partner therapy for Chlamydia trachomatis infection, New York City, 2014–2015. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(11):673–678. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schillinger JA, Gorwitz R, Rietmeijer C, et al. The expedited partner therapy continuum: a conceptual framework to guide programmatic efforts to increase partner treatment. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(2S):S63–S75. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and prevention. Legal Status of Expedited Partner Therapy. [December 05, 2017]; Available from https://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/default.htm.

- 12.EvergreenHealth. Maryland 2015 Pharmacy Directory [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maryland Board of Pharmacy. [May 15, 2017]; Available from: https://health.maryland.gov/pharmacy.

- 14.Baltimore City Health Department (Maryland Department of Health website) [June 9,2017]; Available from https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/OIDPCS/CSTIP/Pages/STI-Data-Statistics.aspx.

- 15.Baltimore City Health Department. Baltimore City 2015 Map of Chlamydia Rates by Zip Code. Available from http://health.baltimorecity.gov/hivstd-data-resources.

- 16. [June 10, 2017];Food Access Research Atlas (United States Department of Agriculture website) Available from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/documentation/

- 17.Census Bureau. [June 10, 2017];2011–2015 ACS 5-year summary file. Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/

- 18. [June 10, 2017];Maryland Code: Health-General § 18–214.1. Available from: https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/OIDPCS/CSTIP/

- 19.Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. [June 10, 2017];Expedited Partner Therapy Regulations. Available from https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/OIDPCS/CSTIP/

- 20.Stopka TJ, Donahue A, Hutcheson M, Green TC. Nonprescription naloxone and syringe sales in the midst of opioid overdose and hepatitis C virus epidemics: Massachusetts, 2015. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57(2S):S34. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qato DM, Daviglus ML, Wilder J, Lee T, Qato D, Lambert B. ‘Pharmacy deserts’ are prevalent in Chicago’s predominantly minority communities, raising medication access concerns. Health Affairs. 2014;33(11):1958–1965. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [July 10, 2017];STDs in Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/minorities.htm.

- 23.Mmeje O, Wallet S, Kolenic G, Bell J. Impact of expedited partner therapy (EPT) implementation on chlamydia incidence in the USA. Sex Transm Infect. 2017 May 17; doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052887. epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drug Enforcement Administration. Valid Prescription Requirements. US Department of Justice; [August 1, 2017]. Available from: https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/manuals/pharm2/pharm_content.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department of Legislative Services. [December 15, 2017];Assessing the Impact of Healthcare Reform in Maryland. Available from http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/Pubs/LegisLegal/2017-Impact-Health-Care-Reform.pdf.

- 26.U.S. Census Bureau. [December 15, 2017];Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2016. Available from https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/demo/p60-260.html.

- 27.Centers for Disease Control. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Guidelines – Special Populations. [December 15, 2017]; Available from https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/specialpops.htm.

- 28.Census Bureau. Relationship Files. [June 17, 2017]; Available from https://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/data/relationship.html.