Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Bone marrow suppression is a common adverse effect of the immunosuppressive drug azathioprine. Polymorphisms in the gene encoding thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) can alter the metabolism of azathioprine, resulting in marrow toxicity and life-threatening infection. In a multicenter cohort of pediatric heart transplant (HT) recipients, we determined the frequency of TPMT genetic variation and assessed whether azathioprine-treated recipients with TPMT variants were at increased risk of infection.

METHODS

We genotyped TPMT in 264 pediatric HT recipients for the presence of the TPMT*2, TPMT*3A, and TPMT*3C variant alleles. Data on infection episodes and azathioprine use were collected as part of each patient's participation in the Pediatric Heart Transplant Study. We performed unadjusted Kaplan-Meier analyses comparing infection outcomes between groups.

RESULTS

TPMT variants were identified in 26 pediatric HT recipients (10%): *3A (n = 17), *3C (n = 8), and *2 (n = 1). Among those with a variant allele, *3C was most prevalent in black patients (4 of 5) and *3A most prevalent among white and Hispanic patients (16 of 20). Among 175 recipients (66%) who received azathioprine as part of the initial immunosuppressive regimen, we found no difference in the number of infections at 1 year after HT (0.7 ± 1.3; range, 0–6 versus 0.5 ± 0.9; range, 0–3; p = 0.60) or in freedom from infection and bacterial infection between non-variant and variant carriers. There was 1 infection-related death in each group.

CONCLUSIONS

In this multicenter cohort of pediatric HT recipients, the prevalence of TPMT variants was similar across racial/ethnic groups to what has been previously reported in non-pediatric HT populations. We found no association between variant alleles and infection in the first year after HT. Because clinically detected cytopenia could have prompted dose adjustment or cessation, we recommend future studies assess the relationship of genotype to leukopenia/neutropenia in the pediatric transplantation population.

Keywords: azathioprine, genetic variation, heart transplantation, infection, pediatrics

Introduction

Successful heart transplantation requires the use of immunosuppressive regimens effective at preventing acute allograft rejection. However, adverse effects associated with immunosuppressive agents, such as bone marrow suppression and increased rates of malignancy and infection, continue to be significant causes of posttransplantation morbidity and mortality.1 For pediatric heart transplant (HT) recipients, infection is an important cause of rehospitalization and is among the leading causes of death in the first year after HT.2

Azathioprine, an immunosuppressive agent commonly used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, inflammatory conditions, and after solid-organ transplantation, can cause myelosuppression that may lead to life-threatening infections.3,4 The risk for azathioprine-induced myelosuppression is particularly high in patients with reduced activity of thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT), an enzyme involved in the metabolism of azathioprine.5 Polymorphisms in TPMT result in variation in enzymatic activity, thiopurine drug effect, and toxicity.6 Individuals with the homozygous wild-type TPMT genotype (*1) have normal enzymatic activity, whereas those with a variant allele (heterozygous) have deficient enzymatic activity.5 Three variant alleles are responsible for 80% to 95% of intermediate and low TPMT enzyme activity: TPMT*2 (G238C; Ala80→Pro), TPMT*3A (G460A and A719G; Ala154→Thr and Tyr240→Cys), and TPMT*3C (A719G; Tyr240→Cys).7,8

In this analysis we sought to investigate the frequency of TPMT genetic variation in a large, multicenter cohort of pediatric HT recipients and to assess whether azathioprine-treated recipients with TPMT variants were at increased risk of infection. We hypothesized that recipients with TPMT variants who are treated with azathioprine are at increased risk of infection.

Materials and Methods

Study Population. The study cohort comprised pediatric HT recipients who underwent transplantation between January 1993 and December 2008 at 1 of 6 centers (University of Pittsburgh, Stanford University, Loma Linda University, Washington University, Columbia University, and University of Alabama at Birmingham). All centers were participants in the Specialized Centers for Clinically Oriented Research (SCCOR) program “Optimizing Outcomes after Pediatric Heart Transplantation,” sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Each pediatric HT recipient was also enrolled in the Pediatric Heart Transplantation Study (PHTS), an international, prospective, event-driven data collection on risk factors and outcomes following listing for transplantation.9 Approval for participant enrollment was obtained from each center's Institutional Review Board, and informed consent (with assent from participants ages 7–17 years, depending on local Institutional Review Board determinations) was obtained before SCCOR study participation. All recipients were maintained on immunosuppressive regimens as per individual institutional protocols.

Data Collection and Clinical Outcomes. Demographic characteristics, clinical outcomes, and infection data for each pediatric HT recipient were extracted from the PHTS database. Methods of data collection, verification, and entry for the PHTS have been described previously.9 Although the PHTS database allows for the collection of data on immunosuppressant use annually after HT, the timing of medication initiations and discontinuations, as well as dosage and frequency, is not captured, limiting inferences that can be drawn from medication follow-up data. However, use of initial immunosuppression (until 30 days after HT) is routinely collected. Thus, we used azathioprine use at 30 days to define individuals at potential risk for TPMT variant–associated infection and limited analysis of infection events to within 1 year of HT. With regard to infections, individual centers collect data when there is clinical “evidence of an infectious process,” including site(s) of infection and organism(s) and/or types of organism(s) (e.g., bacteria, virus, fungus, protozoa) causing infection that require intravenous antimicrobial therapy. Also, centers collect data on “life threatening infection(s) requiring oral therapy.”10,11 Sequelae of infection (i.e., resolution/death) are also recorded.

Detection of Genetic Polymorphisms. Peripheral venous blood (3–6 mL) was obtained from each participant during routine venipuncture. Anticoagulated whole blood was shipped at room temperature to the core laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh within 24 hours, where it was aliquoted and frozen at −80°C until it was batch processed for DNA extraction and amplification using a QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit and a REPLI-g Mini/Midi Kit (Qiagen Inc, Germantown, MD), respectively. Primer pairs were designed on the basis of the gene sequence available at GenBank (NG_012137). Single polymerase chain reaction (PCR; F1/R1) and nested (F1/R1 and F2/R2) primer pairs were: TPMT*2: F1 5′-TCAATCACGAGGAACCAATGTG-3′, R1 5′-ATCTCTTCAATGTCTCAGGCAG-3′, F2 5′-TGGACAGCGACAGATATAGAC-3′, R2 5′-GGTATCCTCATAATACTCACAC-3; TPMT*3A: F1 5′-TGGTTAGCTCCCAAACTATGG-3′, R1 5′-AAGCACATACCACCACGGTCG-3′, F2 5′-TCAAGTAGCCAAGGGAGATAAG-3′, R2 5′-AGTGACCAGTAAGTATTACCTG-3′; and TPMT*3C: F1 5′-AGAATCCCTGATGTCATTCTTC-3′, R1 5′-ACAGGTAACACATGCTGATTGG-3′. Initial PCR reactions were carried out in a 20-mcL reaction mixture containing 5 mcL of patient DNA (~5 ng/mcL), 1× PCR buffer (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 1 mM each primer (i.e., F1 and R1 for TPMT*2 and TPMT*3A), and 1.25 units of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) using a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) as a thermocycler with the following thermal profile (primary PCR): 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 62°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds. TPCR reactions were then carried out in a 50-mcL reaction mixture containing 5 mcL of the initial PCR product (TPMT*2 and TPMT*3A) or patient DNA (TPMT*3C), 1× PCR buffer (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 800 μM each primer (i.e., F2 and R2 for TPMT*2 and TPMT*3A; F1 and R1 for TPMT*3C), and 1.25 units of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) using a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) as a thermocycler with the following thermal profile (primary PCR): 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 62°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds. After amplification, the quality of amplified PCR products was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. A total of 15 mcL of the above product was placed in 5 mcL of the following mixture: 1 unit of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (1 mcL), 3 units of exonuclease 1 (0.35 mcL), 1× dilution buffer for shrimp alkaline phosphatase (0.5 mcL), and 3.15 μL of water (USB, Cleveland, OH). For UGT1A1*60, sequencing PCR was performed with Big Dye (v3.1, Applied Biosystems) using the following PCR primers: TPMT*2: F3 5′-TCCTGCATGTTCTTTGAAACCC-3′, R3 5′-TGGTTCCAGGAATTTCGGTG-3′; TPMT*3A: F3 5′-TGACGATTGTTGAAGTACCAGC-3′, R3 5′-TGAAAGTGATTGAGCCACAAGC-3′; and TPMT*3C: F2 5′-TCCCTGATGTCATTCTTCATAG-3′, R2 5′-GCAATCTGCAAGACACATAGG-3′. The PCR products were then sequenced on an ABI Prism 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) per the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analyses. Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between non-variant and variant carrier groups using the χ2 or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate. We analyzed TPMT allelic frequencies within the entire cohort of HT recipients who underwent TPMT genetic assessment. Infections were assessed among those on azathioprine at 30 days after transplantation. Comparison of infection events at 1 year after transplantation was conducted only among those with at least 1 year of follow-up and was compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Freedom from infection was assessed between non-variant and variant carriers by the Kaplan-Meier technique and log-rank test with censoring at 1 year after transplantation or at time of death or loss to follow-up prior to 1 year after transplantation. As a secondary outcome, freedom from isolated bacterial infection was also analyzed similarly with the rationale that death from neutropenic sepsis while on azathioprine has been reported after HT.4

RESULTS

TPMT Gene Variation. A total of 264 HT recipients (54% male) underwent genetic analysis and had complete data for the TPMT*2, TPMT*3A, and TPMT*3C loci. The cohort was 54% white, 24% Hispanic, and 14% black. TPMT variants were identified in 26 pediatric HT recipients (10%): *3A (n = 17), *3C (n = 8), and *2 (n = 1). We found no significant difference in prevalence of variant alleles by race/ethnicity: white (10%), black (14%), Hispanic (9%), and other (5%); p = 0.83. Among those with a variant allele, *3C was most prevalent in black patients (4 of 5) and *3A most prevalent among white and Hispanic patients (16 of 20). Mean age at HT was similar between the non-variant and variant carriers (5.6 ± 6.0 versus 5.8 ± 5.4 years; p = 0.75).

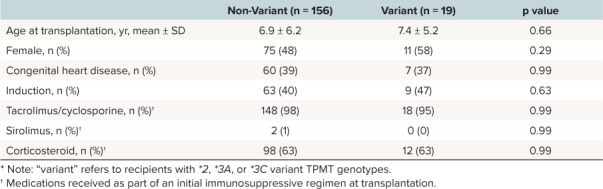

Azathioprine was used as part of the initial immunosuppression regimen in 175 recipients (66%). Mean posttransplantation follow-up was 3.9 ± 2.5 years, with 85% having at least 1 year of follow-up. We found no significant differences in age at HT, sex, underlying cardiac etiology, use of induction therapy, and use of tacrolimus or cyclosporine, sirolimus, or prednisone/prednisolone as part of the initial immunosuppression regimen (Table).

Table 1.

Table.Baseline Characteristics of Recipients Treated With Azathioprine, Stratified by Thiopurine S-Methyltransferase (TPMT) Variant Carrier Status *

Genetic Polymorphisms and Infection. Overall, 90 recipients (51%) treated with azathioprine experienced at least 1 infection in the first year after transplantation, including 53% (82 of 156) of non-variant carriers and 42% (8 of 19) of variant carriers (p = 0.47). We observed no significant difference in the number of infections (0.8 ± 1.4; range, 0–7 versus 0.6 ± 1.0; range, 0–3; p = 0.93) and bacterial infections (0.4 ± 0.9; range, 0–5 versus 0.3 ± 0.6; range, 0–2; p = 0.93) between non-variant and variant carriers in the first year after HT.

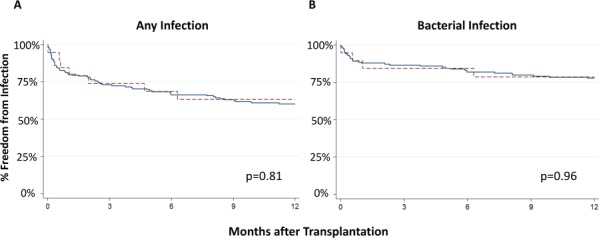

Freedom from any infection and bacterial infection are shown in the Figure. We found no significant differences in these outcomes. We also examined outcomes of recipients with variants associated with the lowest enzymatic activity (TPMT*2 and TPMT*3A) and found no differences relative to non-variant carriers (log rank p > 0.68 for both).

Figure.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing freedom from a) any infection and b) bacterial infection for non-variant versus thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) variant carriers in the first year after pediatric heart transplantation. The solid line indicates non-variant carriers.

Infection-related mortality was reported in 2 recipients: 1 TPMT*3A variant carrier who received HT at age 16 years and died of infection with Epstein-Barr virus at 72 days after HT, and 1 non-carrier who received HT at age 15 days and died of infection from vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus species at 258 days after HT.

Discussion

In this multicenter study of pediatric HT recipients, we found that TPMT variant alleles were present in expected proportions according to race/ethnicity. We also found no association between the outcomes of infection, bacterial infection, and infection-related mortality with the presence of TPMT*2, TPMT*3A, and TPMT*3C variant alleles. To our knowledge, this is the only study examining TPMT allelic frequency and association of TPMT genotype with infection in pediatric HT recipients. In previous studies among adults with inflammatory bowel disease or solid-organ transplantation, an increased risk of azathioprine-related toxicity in the form of leukopenia or broader myelosuppression was observed among heterozygotes with TPMT*2, TPMT*3A, or TPMT*3C variant alleles.12–15 This includes a study of adult HT recipients receiving azathioprine in which neutrophil and leukocyte counts were lower among patients who carried either *3A or *3C variants.15 However, this study followed patients only up to the first month after HT and did not evaluate the impact of TPMT variant alleles on infection.

Although leukopenia predisposes individuals with neutrophil counts lower than 500 cells per mm3 to serious bacterial infection, it is possible that infection is not an immediate enough outcome to assess TPMT variant status. Children after HT, particularly soon after HT, undergo frequent laboratory assessment. Thus, it is possible that we did not observe an association between infection and TPMT variant status because azathioprine-related toxicity among TPMT variant carriers was recognized and ameliorated prior to the development of infection. Unfortunately, we were not able to analyze white blood cell or neutrophil counts in the study population, because neither is collected in the PHTS data set. Although we analyzed infection-related mortality, there were only 2 such reported deaths observed in our cohort, limiting the utility of this outcome.

It is also possible that we lacked sufficient power to observe a difference in outcomes. Post hoc power analyses show that with a 2-sided a of 0.05, we had 80% power to detect a 64% difference in infection between the groups. Further exploratory analysis showed that assuming the same prevalence of TPMT variants that we observed, we would have needed 295 genotyped recipients, including 32 withTPMT variants, to provide 80% power to detect a 50% difference in infection among the groups. Furthermore, it would have required 1965 recipients, including 211 with TPMT variants, to detect a 20% difference in infection between the groups. These analyses suggest that although our multicenter cohort is the largest pediatric HT cohort to undergo genetic testing in this fashion, we would require at least twice as many patients to be able to observe a 50% difference in infection.

Other important limitations of our analysis include the lack of precise data on azathioprine dosages and duration of use, and lack of plasma azathioprine concentration data. Also, although we did assess recipients with TPMT variants associated with the lowest activity levels (*2 and *3A), our study population was not large enough to identify and define infection risk for the very rare recipient with homozygous variant state. The era in which some of the earliest patients in our cohort received HT (early to mid 1990s) may limit generalizability to the care of patients in the current era. Also, aside from the fact that there was no difference in age of the groups at HT, we could not account for any possible differences in potential infectious exposures in the groups, such as seasonality and siblings.

In summary, we found TPMT allelic variants predisposing individuals to bone marrow toxicity are present in 10% of pediatric HT recipients from a large, multicenter cohort. TPMT*3C was most common in black recipients, whereas TPMT*3A was most common in white and Hispanic recipients. Infection in the first year after HT was similar between recipients with and without a TPMT variant, with no difference in infection-related mortality between the groups. Because clinically detected cytopenia could have prompted dose adjustment or cessation, we recommend future studies also look at the relationship of genotype to leukopenia/neutropenia in pediatric solid-organ transplant populations.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (5P50 HL07432-05). The laboratory work was funded by the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the US Food and Drug Administration.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HT

heart transplant

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PHTS

Pediatric Heart Transplantation Study

- SCCOR

Specialized Centers for Clinically Oriented Research

- TPMT

thiopurine S-methyltransferase

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Copyright Published by the Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group. All rights reserved. For permissions, email: matthew.helms@ppag.org

REFERENCES

- 1. Schonder KS, Mazariegos GV, Weber RJ.. Adverse effects of immunosuppression in pediatric solid organ transplantation. Paediatr Drugs. 2010; 12 1: 35– 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dipchand AI, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, . et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: seventeenth official pediatric heart transplantation report--2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014; 33 10: 985– 995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Connell WR, Kamm MA, Ritchie JK, . et al. Bone marrow toxicity caused by azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: 27 years of experience. Gut. 1993; 34 8: 1081– 1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schütz E, Gummert J, Mohr F, . et al. Azathioprine-induced myelosuppression in thiopurine methyltransferase deficient heart transplant recipient. Lancet. 1993; 341 8842: 436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nguyen CM, Mendes MA, Ma JD.. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) genotyping to predict myelosuppression risk. PLoS Curr. 2011; 3: RRN1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McLeod HL, Siva C.. The thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene locus--implications for clinical pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics. 2002; 3 1: 89– 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tai HL, Krynetski EY, Yates CR, . et al. Thiopurine S-methyltransferase deficiency: two nucleotide transitions define the most prevalent mutant allele associated with loss of catalytic activity in Caucasians. Am J Hum Genet. 1996; 58 4: 694– 702. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yates CR, Krynetski EY, Loennechen T, . et al. Molecular diagnosis of thiopurine S-methyltransferase deficiency: genetic basis for azathioprine and mercaptopurine intolerance. Ann Intern Med. 1997; 126 8: 608– 614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hsu DT, Naftel DC, Webber SA, . et al. Lessons learned from the pediatric heart transplant study. Congenit Heart Dis. 2006; 1 3: 54– 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pediatric Heart Transplant Study: forms and manuals. February 12, 2017. https://www.uab.edu/medicine/phts/forms-and-manuals. Accessed February 19, 2018.

- 11. Schowengerdt KO, Naftel DC, Seib PM, . et al. Infection after pediatric heart transplantation: results of a multi-institutional study: he Pediatric Heart Transplant Study Group. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1997; 16 12: 1207– 1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kurzawski M, Dziewanowski K, Lener A, . et al. TPMT but not ITPA gene polymorphism influences the risk of azathioprine intolerance in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009; 65 5: 533– 540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fabre MA, Jones DC, Bunce M, . et al. The impact of thiopurine S-methyltransferase polymorphisms on azathioprine dose 1 year after renal transplantation. Transpl Int. 2004; 17 9: 531– 539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zelinkova Z, Derijks LJ, Stokkers PC, . et al. Inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase and thiopurine s-methyltransferase genotypes relationship to azathioprine-induced myelosuppression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 4 1: 44– 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sebbag L, Boucher P, Davelu P, . et al. Thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene polymorphism is predictive of azathioprine-induced myelosuppression in heart transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000; 69 7: 1524– 1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]