Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Optimization of vancomycin dosing is difficult in children, given rapid drug clearance and patient heterogeneity. We sought to evaluate the impact of dosing using individual pharmacokinetic parameters on time to goal trough concentration in pediatric oncology patients.

METHODS

A retrospective review was conducted to assess vancomycin dosing in the pediatric oncology unit at Loma Linda University Children's Hospital between January 2013 and August 2013 (standard dosing group [SDG]). These patients were compared to those in a prospective arm that used pharmacokinetic dosing (pharmacokinetic dosing group [PKG]) between March 2014 and May 2015. Outcomes included percent of patients reaching a target trough by the specified time points, number of dose adjustments, number of serum concentrations drawn, and number of patients with supratherapeutic troughs.

RESULTS

Of 35 patients meeting inclusion criteria for the SDG, 2 (5.7%) reached goal trough concentration by 48 hours, compared with 14 of 16 patients (87%) in the PKG (p = 0.0001). Significantly more patients reached their goal trough at each time point in the PKG. There was no difference in number of dose adjustments, but significantly more concentrations were drawn on average in the PKG (mean, 4.6 versus 3.1, p = 0.02). In the SDG and PKG, respectively, 1 patient and 3 patients had supratherapeutic trough concentrations (p = 0.09).

CONCLUSIONS

Dosing using individual pharmacokinetic parameters led to a significant reduction in time to attain the desired vancomycin trough concentration in our pediatric oncology patients. Given the wide variation in dose requirements in this and other studies, application of patient-specific pharmacokinetics is essential to optimize vancomycin dosing in pediatric patients.

Keywords: oncology, pediatrics, pharmacokinetics, Sawchuk-Zaske, therapeutic drug monitoring, vancomycin

Introduction

Optimization of vancomycin dosing in pediatrics is difficult given the rapid drug elimination and large doses often required to achieve adequate serum concentrations. Differences in patient age, weight, comorbidities, renal function, and volume of distribution can complicate dosing such that one standard weight-adjusted dose and frequency has a small probability of attaining goal concentrations for all patients within a demographic. Recent studies have suggested that vancomycin dosages from 60 to 85 mg/kg/day may be needed to achieve trough concentrations between 10 and 20 mg/L in pediatric patients.1–3 However, a wide range of dose requirements was seen in these studies, with a number of patients still above and below the goal range. Data from special pediatric populations, including critically ill, obese, burn, and oncology patients, suggest even more variability in vancomycin dose requirements.4–7

Clearly, individualization of vancomycin dosing is needed in pediatric patients. Dosing strategies such as Bayesian modeling have previously been suggested to optimize vancomycin concentrations in children.7–10 However, models constructed in these studies often rely on simulation and population pharmacokinetics, which may be limited in their ability to predict dosing for individual patients. In 1976, Sawchuk and Zaske11 described a method to optimize gentamicin dosing using individual patient pharmacokinetic parameters, which has since been applied to vancomycin. The Sawchuk-Zaske method performs similarly to Bayesian modeling for aminoglycoside dosing,12,13 but data comparing these methods for vancomycin dosing are limited, especially in pediatrics. One study in adults suggested that Bayesian modeling was less biased than the Sawchuk-Zaske method in predicting vancomycin peak and trough concentrations.14 However, the Sawchuk-Zaske method has the advantage of calculations that can easily be performed, which may be more practical in institutions without access to a Bayesian modeling program.

As part of a recent quality and safety initiative at Loma Linda University Children's Hospital, it was decided to pilot vancomycin dosing using individual pharmacokinetic parameters and the Sawchuk-Zaske method in the pediatric oncology unit. The unit was selected because these patients are often at risk for Gram-positive infections for which the rapid attainment of adequate vancomycin concentrations is desirable.15–18 The objective of this study was to investigate the impact of dosing using individual pharmacokinetic parameters compared with standard dosing on time to achieve desired vancomycin trough concentrations in pediatric oncology patients.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the Loma Linda University Children's Hospital Institutional Review Board prior to study commencement.

Patient Selection. Patients were compared in 2 distinct time periods—both before and after implementation of pharmacokinetic dosing in the pediatric oncology unit at our institution. Patients were included in a retrospective chart review for the standard dosing group (SDG) if they were admitted to the unit between January and August 2013, were from ages 2 to younger than 13 years, had a creatinine clearance of ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 upon vancomycin initiation as determined by the Schwartz equation,19 received ≥5 days of vancomycin, and had at least 1 trough concentration drawn. Patients were included in the prospective pharmacokinetic dosing group (PKG) if they were admitted to the unit from March 2014 to May 2015, were between ages 2 and younger than 13 years, had a creatinine clearance of ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 upon vancomycin initiation, received ≥5 days of vancomycin, began a vancomycin regimen based on individual pharmacokinetic parameters starting ≤48 hours from the first dose, and were not at the physician-specified goal trough at the time of pharmacy consultation.

Vancomycin Dosing and Monitoring. All vancomycin doses in both groups were infused at a rate of 10 mg/kg/hr. Blood samples for determination of vancomycin serum trough concentrations were collected within 30 minutes prior to the next dose. Concentrations were determined from serum using standard laboratory procedures throughout the study period with a commercially available assay. During the SDG time period, starting vancomycin dosages in the oncology unit were typically around 40 mg/kg/day, given as 10 mg/kg every 6 hours. Because of internal data and published studies1–3 suggesting that this regimen often resulted in subtherapeutic concentrations, starting dosages were typically higher in the PKG—often 60 mg/kg/day, given as 15 mg/kg every 6 hours.

In the SDG, vancomycin troughs were obtained and dose adjustments were made by the prescribing physician. Goal trough ranges for the SDG (specified by the physician as either 10–15 mg/L or 15–20 mg/L) were determined from progress notes via retrospective chart review. In the PKG, the prescribing physician specified the goal trough range (10–15 mg/L or 15–20 mg/L) at the time pharmacy was consulted for dosing. From that point on, vancomycin doses, frequencies, and concentrations were ordered by a pharmacist with infectious diseases training or by a pharmacy resident with infectious diseases pharmacist oversight. Vancomycin could be discontinued at the discretion of the prescribing physician.

In the PKG, if pharmacy was consulted at the time of vancomycin initiation, 2 consecutive serum concentrations were obtained after the first dose. If pharmacy was consulted after multiple doses had been administered, 3 concentrations were obtained surrounding the next scheduled dose (a trough before and 2 consecutive concentrations after the dose). The Sawchuk-Zaske method11 was used to manually calculate the patient's vancomycin elimination rate constant, half-life, and volume of distribution. Sawchuk and Zaske describe the pharmacokinetic equations and calculations in a step-by-step process in their paper.11 Dose adjustments were then made at the discretion of the pharmacist using these patient-specific pharmacokinetic values. If the pharmacokinetic-calculated dose was unreasonably high, lower doses could be selected. Subsequent trough concentrations drawn after at least 4 half-lives on the same dosing regimen were assumed to represent steady-state and were used to determine attainment of the goal trough concentration. If the steady-state trough concentration was not within the physician-specified goal range, the vancomycin dose was adjusted proportionally to the desired change in trough.

The primary outcome of the study was to compare the percent of patients who reached goal trough concentrations by 48 hours in the SDG and the PKG. Secondary outcomes included: percent of patients who reached goal trough concentrations in 24 hours, 5 days, and 7 days; average trough concentration achieved at each of these time points; number of dose adjustments needed to reach goal; total number of trough concentrations drawn; number of patients with trough concentrations exceeding the goal range; and number of patients with troughs >20 mg/L at any time.

Statistical Analysis. Because of the small sample size, categorical data were analyzed using Fisher's exact test. Continuous data were analyzed using a 2-sided unpaired t-test. All calculations were performed using GraphPad Software accessible at http://www.graphpad.com. A p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients. Of 75 patients screened retrospectively, 35 met inclusion criteria for the SDG, and 16 of 17 patients who received pharmacokinetic dosing were included in the prospective PKG. Most patients excluded from the SDG were excluded because of a vancomycin treatment course <5 days. One patient was excluded from the PKG because the pharmacy consult occurred more than 48 hours after vancomycin initiation. Baseline characteristics, shown in Table 1, suggested no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups. There was higher baseline creatinine clearance and more males versus females in the SDG than in the PKG, but these differences were not significant (p = 0.12 and 0.13, respectively). Both groups had a larger proportion of patients with goal vancomycin trough concentrations of 10 to 15 mg/L versus 15 to 20 mg/L. The most common indication for vancomycin was neutropenic fever (53% of all patients), followed by cellulitis (10%), line infection (8%), and pneumonia (8%).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Demographics

Vancomycin Dosing and Monitoring. Vancomycin dosing and monitoring in both groups is shown in Table 2. Of note, there was a significant difference in mean starting dosage between groups—approximately 45 mg/kg/day in the SDG versus 60 mg/kg/day in the PKG for both goal trough ranges (p < 0.01 for goal trough range 10–15 mg/L and p = 0.03 for 15–20 mg/L). Despite this discrepancy, patients in both groups who met the goal trough concentration still required considerable dose increases: on average, an additional 28 mg/kg/day to achieve 10 to 15 mg/L and an additional 50 to 60 mg/kg/day to achieve 15 to 20 mg/L. A wide range of dosage requirements was observed to achieve a trough concentration of 10 to 15 mg/L—52 to 205 mg/kg/day. There were 6 patients who required 60 mg/kg/day or less to reach 10 to 15 mg/L, whereas 4 patients required 100 mg/kg/day or more.

Table 2.

Vancomycin Dosing and Monitoring

There was no difference in the average number of dose adjustments between groups, but significantly more concentrations were drawn on average in the PKG during the first 7 days of therapy (4.6 versus 3.1 concentrations per patient, p = 0.02). Interestingly, although the PKG starting dose was significantly larger, the mean percent dose change with each adjustment was also significantly higher than in the SDG (38.8% ± 25.4% versus 25.2% ± 20.5%, respectively; p = 0.05), suggesting that dosing in the PKG was more aggressive.

Primary Outcome. As seen in Figure 1, there were 2 of 35 patients (5.7%) in the SDG who reached their stated trough goal by 48 hours compared with 14 of 16 patients (87%) in the PKG (p = 0.0001). For most PKG patients, pharmacokinetic calculations were made based on concentrations obtained in the first 24 hours. The average time from vancomycin initiation to administration of a pharmacist-recommended dose based on these calculations was 28 hours. Following the dose adjustment, troughs were rarely obtained more frequently than every 24 hours; therefore, the impact of recommendations based on individual pharmacokinetics was best represented by the 48-hour time point forward. The 48-hour time point was judged to represent steady-state conditions of the pharmacist-recommended dose in most patients based on the short half-lives observed. Means ± SDs for vancomycin half-life and volume of distribution in the PKG were 1.7 ± 0.13 hours (range, 1.5–1.9 hours), and 9.2 ± 2.0 L (range, 5.7–12 L), respectively.

Figure 1.

Percent of patients at specified goal vancomycin trough concentration at various time points.

Secondary Outcomes. At each of the measured time points (24 hours, 5 days, and 7 days) a higher percentage of patients in the PKG achieved goal trough concentrations. All of these differences were found to be statistically significant (Figure 1). In the SDG, 15 of 35 patients (43%) never reached the goal trough concentration during the first 7 days of therapy, whereas all 16 patients in the PKG achieved the goal trough by 7 days.

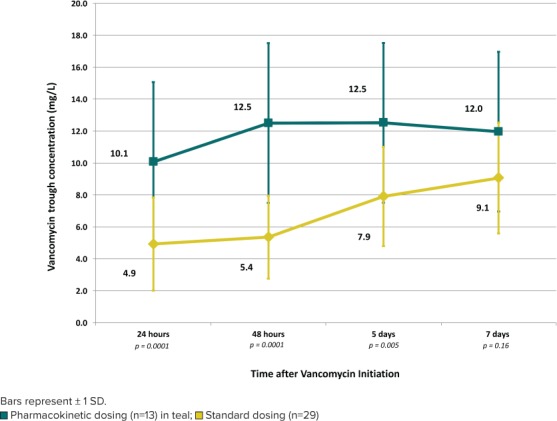

Figure 2 depicts patients with a goal trough concentration of 10 to 15 mg/L. The average vancomycin trough in the SDG was below the goal range throughout the first 7 days of therapy. In the PKG, the average trough concentration achieved by 24 hours was 10.1 mg/L, and it remained within the 10 to 15 mg/L range during the first 7 days of therapy. Statistically significant differences were seen between the groups at each of the evaluated time points, except for day 7, by which time the average trough in the SDG had increased to 9.1 mg/L.

Figure 2.

Average vancomycin trough concentration by time for patients with a goal of 10 to 15 mg/L.

Similarly, for patients with a trough goal of 15 to 20 mg/L, the average vancomycin trough in the SDG (n = 6 patients) was still subtherapeutic by Day 7, whereas the average trough was within the goal range by 48 hours in the PKG (n = 3 patients). Significant differences were seen between the SDG and PKG at 24 hours (4.8 versus 9.0 mg/L, p = 0.04, respectively) and 48 hours (4.7 versus 18.0 mg/L, p = 0.001, respectively). Average troughs in the SDG were 7.2 and 9.4 mg/L at days 5 and 7 compared with 16.9 and 16.6 mg/L, respectively, in the PKG, but statistics were unable to be calculated at these time points because of the small sample size (only 1 patient with goal range 15–20 mg/L in the PKG had concentrations for evaluation at days 5 and 7).

Results for the remaining secondary end points are described in Table 2. There were more patients with trough concentrations above the physician-specified goal range in the PKG; however, this did not meet statistical significance (p = 0.09). Only 1 patient in the PKG had a trough concentration greater than 20 mg/L, compared with no patients in the SDG. For additional safety monitoring, serum creatinine (SCr) trends in both groups were reviewed. In the SDG, 11 patients had an increase in SCr while on vancomycin, but 10 of these instances involved a small increase from 0.2 to 0.3 mg/dL. Only 1 patient had a significant increase from 0.4 to 1.0 mg/dL. In the PKG, 3 patients had an increase in SCr; one from 0.2 to 0.5 mg/dL, another from <0.2 to 0.3 mg/dL, and the third from <0.2 to 0.2 mg/dL. The first patient required a decrease in vancomycin dose to keep the trough concentration within the desired target range. All other patients either had no change or a slight decrease in SCr during the study period.

Discussion

Previous studies suggest that delays in initiation of effective antibiotics can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.20,21 However, even when vancomycin is initiated in a timely manner for severe Gram-positive infections, delays in achieving an adequate trough concentration can lead to inferior clinical outcomes.17,18 This is particularly concerning in pediatric patients, considering their tendency to have low concentrations due to a short vancomycin half-life. In our study, large increases in dose were needed to achieve goal concentrations, even when patients were started at a dosage of 60 mg/kg/day. It was particularly striking that 43% of patients in the SDG had not yet reached the stated goal trough range by day 7 of vancomycin therapy.

To avoid such a prolonged period of potentially subtherapeutic concentrations, it is tempting to recommend higher empiric dosing for this patient population. However, this would not have been appropriate for some patients in our study because 6 patients required 60 mg/kg/day or less to reach a trough concentration between 10 and 15 mg/L. Overall, dosages required to achieve trough concentrations between 10 and 15 mg/L ranged from 52 to 205 mg/kg/day. Wide variation in vancomycin dose requirements is consistent with previous studies in pediatric patients.1–7 We believe this highlights the importance of dosing individualization to avoid toxicity from high concentrations and any potential delay in efficacy or development of resistance from low concentrations.22,23

Our data suggest that dosing using individual pharmacokinetic parameters allowed for rapid attainment of goal troughs in the PKG, whereas significant delays were seen in the SDG. Regarding the pharmacokinetic calculations, it is important to note that the Sawchuk-Zaske method relies on 2 consecutive postdistributional concentrations to calculate pharmacokinetic parameters based on a 1-compartment model.11 Many of the first concentrations in the PKG were drawn around 3 hours after infusion; therefore, elimination half-lives could have been overestimated due to the possibility of vancomycin still being in its distribution phase.8 Lower doses than those calculated were occasionally used for this reason, yet the pharmacokinetic calculations provided confidence in more aggressive dosing and led to achievement of desired troughs significantly faster than in the SDG. Although this dosing strategy came at the cost of additional concentrations being drawn and a small number of patients above goal trough range, it provided the greater benefit of adequate dosing in the first 48 hours for most PKG patients.

Current guidelines for vancomycin dosing in adults recommend trough concentration goals between 10 and 15 mg/L or 15 and 20 mg/L, depending on the indication, to achieve an area under the curve–minimum inhibitory concentration ratio of ≥400:1,24 although the studies supporting these recommendations have significant limitations. Recent pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies in pediatric patients suggest that this 400:1 ratio may be achieved with lower troughs (i.e., between 7 and 10 mg/L),25,26 but the average troughs achieved by 48 hours in the SDG were subtherapeutic even for these lower goals.

Clinical outcomes of the patients were not assessed in this study because the primary focus was on dosing optimization and the overall sample size was small. For the safety evaluation, increases in SCr were seen in 11 patients in the SDG versus 3 patients in the PKG. Many patients had an increase of only 0.1 mg/dL, and the test for SCr in our laboratory is linear down to 0.2 mg/dL with a coefficient of variation of 1% to 2.5%. The small increase in SCr may or may not be meaningful, and the small number of patients in each group precluded meaningful statistical comparison. Despite this, we believe the significant decrease in time to goal trough concentrations in the PKG with few high concentrations represents a potential improvement in patient care in our pediatric oncology unit without compromising safety. Future studies are needed to validate that our pharmacokinetics-based approach and shorter time to goal vancomycin trough concentrations lead to improved outcomes in this patient population.

Our study did have a number of limitations that may have biased the results. The most notable of these was that the SDG was started on a significantly lower dose than the PKG (approximately 45 mg/kg/day versus 60 mg/kg/day, respectively). This reflected an evidence-based change in vancomycin dosing in our oncology unit between the 2 studied time periods, and we considered it unethical to start the PKG patients on lower dosing for the sake of equal comparison. The SDG likely had lower concentrations in the first 24 to 48 hours due to the lower starting dose. However, it is important to consider that this difference between groups persisted for up to 7 days after vancomycin initiation, and that nearly 43% of patients never reached their goal trough by 7 days in the SDG. These differences led us to 2 conclusions: (1) 45 mg/kg/day was too low for empiric dosing in these patients, and (2) that appropriate dose adjustments were not being made based on the vancomycin concentrations in the SDG. Table 2 shows that although the SDG was started on significantly lower doses, the average dose change with each adjustment was still significantly smaller than in the PKG. Discussion with providers on the unit suggested there was a certain degree of discomfort in making aggressive dose changes based on the trough concentration alone, but that calculation of a patient's dose requirements from his or her half-life and volume of distribution provided more confidence in large dose increases.

Another important limitation was the small sample size overall and the retrospective review of vancomycin dosing in the SDG. It is possible that the dosing seen in the 35 included patients is not representative of the whole population in the pediatric oncology unit. Also, if additional patients had been enrolled in the prospective PKG, a significant difference may have been found in the number of patients with supratherapeutic trough concentrations. There were notably more patients in the retrospective SDG than in the prospective PKG. Enrollment was limited by the small number of provider requests for consultation and by the pharmacist's ability to identify patients for consultation in a timely manner. To address this issue, we attempted an additional enrollment period from March through May 2015, during which only 2 additional patients were enrolled. The statistical results were not significantly impacted by the inclusion or exclusion of these patients. Despite the smaller sample size of the PKG overall, significant differences in our primary and secondary end points were still found when compared with the SDG.

Lastly, data from this study are not sufficient to show superiority of using individual pharmacokinetic parameters over other dosing methods. An important limitation to note is that the prospective PKG was dosed specifically with the goal of rapid target achievement, which introduced an inherent bias to the study design. However, considering the variability in vancomycin dose requirements in this and other pediatric studies, we still advocate using patient-specific pharmacokinetics rather than population averages or nomograms to optimize vancomycin dosing in our pediatric patients.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, dosing using patient-specific pharmacokinetic parameters significantly improved time to goal vancomycin troughs in our pediatric oncology patients. The variability in vancomycin dose requirements in this and other studies highlights the importance of individualized dosing in pediatric patients. As such, we believe that calculation of individual pharmacokinetic parameters is essential to optimize vancomycin dosing in such a heterogeneous population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the nurse practitioners, nursing staff, pharmacists, physicians, and administrators of Loma Linda University Children's Hospital for their help and support in this study. Some of these data have been presented in Abstract and PowerPoint format at the Western States Pharmacy Residency Conference; San Diego, California; 2014.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PKG

pharmacokinetic dosing group

- SCr

serum creatinine

- SDG

standard dosing group

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Copyright Published by the Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group. All rights reserved. For permissions, email: matthew.helms@ppag.org

REFERENCES

- 1. Broome L, So TY.. An evaluation of initial vancomycin dosing in infants, children, and adolescents. Int J Pediatr. 2011; 2011: 470364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eiland LS, English TM, Eiland EH III. . Assessment of vancomycin dosing and subsequent serum concentrations in pediatric patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2011; 45 5: 582– 589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Madigan T, Sieve RM, Graner KK, . et al. The effect of age and weight on vancomycin serum trough concentrations in pediatric patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2013; 33 12: 1264– 1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glover ML, Cole E, Wolfsdorf J.. Vancomycin dosage requirements among pediatric intensive care unit patients with normal renal function. J Crit Care. 2000; 15 1: 1– 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heble DE Jr, McPherson C, Nelson MP, . et al. Vancomycin trough concentrations in overweight or obese pediatric patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2013; 33 12: 1273– 1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gomez DS, Campos EV, de Azevedo RP, . et al. Individualised vancomycin doses for paediatric burn patients to achieve PK/PD targets. Burns. 2013. May; 39 3: 445– 450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao W, Zhang D, Fakhoury M, . et al. Population pharmacokinetics and dosing optimization of vancomycin in children with malignant hematological disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014; 58 6: 3191– 3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wrishko RE, Levine M, Khoo D, . et al. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics and Bayesian estimation in pediatric patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2000; 22 5: 522– 531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Le J, Ngu B, Bradley JS, . et al. Vancomycin monitoring in children using bayesian estimation. Ther Drug Monit. 2014; 36 4: 510– 518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hahn A, Frenck RW Jr, Zou Y, . et al. Validation of a pediatric population pharmacokinetic model for vancomycin. Ther Drug Monit. 2015; 37 3: 413– 416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sawchuk RJ, Zaske DE.. Pharmacokinetics of dosing regimens which use multiple intravenous infusions: gentamicin in burn patients. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1976; 4 2: 183– 195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodvold KA, Blum RA.. Predictive performance of Sawchuk-Zaske and Bayesian dosing methods for tobramycin. J Clin Pharmacol. 1987; 27 5: 419– 424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burton ME, Chow MS, Platt DR, . et al. Accuracy of Bayesian and Sawchuk-Zaske dosing methods for gentamicin. Clin Pharm. 1986; 5 2: 143– 149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garrelts JC, Godley PJ, Horton MW, Karboski JA.. Accuracy of Bayesian, Sawchuk-Zaske, and nomogram dosing methods for vancomycin. Clin Pharm. 1987; 6 10: 795– 799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miedema KG, Winter RH, Ammann RA, . et al. Bacteria causing bacteremia in pediatric cancer patients presenting with febrile neutropenia--species distribution and susceptibility patterns. Support Care Cancer. 2013; 21 9: 2417– 2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, . et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 52 4: 427– 431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zimmermann AE, Katona BG, Plaisance KI.. Association of vancomycin serum concentrations with outcomes in patients with gram-positive bacteremia. Pharmacotherapy. 1995; 15 1: 85– 91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kullar R, Davis SL, Levine DP, . et al. Impact of vancomycin exposure on outcomes in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: support for consensus guidelines suggested targets. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 52 8: 975– 981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM Jr, . et al. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics. 1976; 58 2: 259– 263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, . et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34 6: 1589– 1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA, . et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 2010; 38 4: 1045– 1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sakoulas G, Eliopoulos GM, Moellering RC Jr, . et al. Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator (agr) group II: is there a relationship to the development of intermediate-level glycopeptide resistance? J Infect Dis. 2003; 187 6: 929– 938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sakoulas G, Gold HS, Cohen RA, . et al. Effects of prolonged vancomycin administration on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a patient with recurrent bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006; 57 4: 699– 704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer JC, . et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009; 66 1: 82– 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frymoyer A, Guglielmo BJ, Hersh AL.. Desired vancomycin trough serum concentration for treating invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcal infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013; 32 10: 1077– 1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Le J, Bradley JS, Murray W, . et al. Improved vancomycin dosing in children using area under the curve exposure. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013; 32 4: e155– e163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]