Abstract

Background

Although dialysis may not provide a large survival benefit for older patients with kidney failure, few are informed about conservative management (CM). Barriers and facilitators to discussions about CM as well as nephrologists’ decisions to present the option of CM may vary within the nephrology provider community.

Study Design

Interview study of nephrologists

Setting & Participants

National sample of US nephrologists sampled based on gender, years in practice, practice type, and region.

Methodology

Qualitative semi-structured interviews continued until thematic saturation.

Analytical Approach

Thematic and narrative analysis of recorded and transcribed interviews.

Results

Among 35 semi-structured interviews with nephrologists from 18 practices, 37% described routinely discussing CM (“early adopters”). Five themes and related subthemes reflected issues that influence nephrologists’ decisions to discuss CM and their approaches to these discussions: struggling to define nephrologists’ roles (determining treatment, instilling hope, improving patient symptoms), circumventing end-of-life conversations (contending with prognostic uncertainty, fearing emotional backlash, jeopardizing relationships, tailoring information), confronting institutional barriers (time constraints, care coordination, incentives for dialysis, discomfort with varied CM approaches), CM as “no care”, and moral distress. Nephrologists’ approaches to CM discussions were shaped by perceptions of their roles and by a common view of CM as “no care”. Their willingness to pursue CM was influenced by provider-level and institutional-level barriers and experiences with older patients who regretted or had been harmed by dialysis (moral distress). Early adopters routinely discussed CM as a way of relieving moral distress, whereas others who were more selective in discussing CM experienced greater distress.

Limitations

Participants’ views are likely most transferable to large academic medical centers, due to oversampling of academic clinicians.

Conclusions

Our findings clarify how moral distress serves as a catalyst for CM discussion and highlight points of intervention and mechanisms potentially underlying low CM use in the United States.

Keywords: geriatric nephrology, dialysis, conservative management, patient-centered outcomes, qualitative methods, shared decision-making, end-of-life planning, qualitatitive study, semi-structured interviews, palliative care, elderly, quality of life, chronic kidney disease (CKD), advanced CKD

For many older adults (defined here as older than 75 years) with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD), dialysis may not confer significant survival benefit over conservative management (CM).1–3 Yet over the past 20 years, dialysis incidence and prevalence in this population has increased more than in any other age group. Independence, symptom burden, and utilization of intensive end-of-life care often differ significantly between patients electing dialysis and those electing CM,4 indicating that choice should be individualized and based on patient preferences.5–8 However, many older CKD patients remain unaware of CM, do not perceive dialysis initiation as a choice, and experience regret associated with dialysis.9–11 Despite growing recognition of CM within the nephrology community, the extent to which nephrologists discuss CM as part of routine care for older adults with CKD, the content and uniformity of care discussions, and barriers to CM discussions remain unclear.12,13 Aligning treatment with patient goals remains an unmet need among many older adults with advanced CKD.9,14–18

Although clinical guidelines support shared decision-making, it remains underutilized in treatment of older CKD patients.9,19 Factors contributing to differences in nephrologists’ decisions to discuss CM remain incompletely understood.20–24 Better understanding these factors may inform strategies to improve patient-centered care. In this qualitative study, we examine how nephrologists decide whether to discuss CM with older patients, and identify triggers for CM discussion and the barriers and facilitators to discussion. We also explore nephrologists’ beliefs, experiences, and challenges in engaging older patients in discussions about CM.

Methods

Participant Selection

A literature review identified factors associated with conversations about CM or advance care planning, from which the team selected purposive sampling criteria using a deliberative process. Criteria included: gender, years in practice, practice type, and region. Three nephrologists (D.E.W., K.B.M., and R.D.P.) then compiled a list of diverse nephrology practices based on the sampling criteria from selected states representing regional and demographic diversity. The qualitative team purposively sampled from the list to capture a range of perspectives. Sampling continued until thematic saturation and sufficient variation in sampling strata were achieved and confirmed through deliberation for each strata.26 To assess the potential impact of center-based culture, at 50% of sites we used snowball sampling,26 allowing participants to recommend other nephrologists from their center.

Data Collection

A social scientist with expertise in qualitative methods and kidney disease (K.L.) and a nephrologist (D.E.W.) used literature and clinical experiences to develop the semi-structured interview guide. 9,15 Open-ended questions explored factors influencing nephrologists’ beliefs and practices regarding CM, characterizing their approach to conversations with older patients with CKD, tailoring of conversations to specific populations, and shared decision-making (Item S1). Nephrologists were asked to reflect on salient clinical examples.

The Tufts University Institutional Review Board approved this study. Authors K.L. and R.P. conducted interviews from July 2016 to May 2017 in person or by phone, as the participant preferred, following oral informed consent. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Researchers (K.L., R.P., A.K., T.O., R.L.; hereafter referred to as the “qualitative team”) trained in qualitative interviewing, transcription, coding, and theme development met weekly to review interviews.

Analysis

Authors K.L. and R.P. used thematic and narrative analytic approaches. Using deductive coding following a topic guide, they created a preliminary codebook.26,27 They independently coded the first three transcripts line-by-line, allowing new codes to emerge inductively.28 The qualitative team revised the codebook, independently recoded the initial three transcripts and an additional randomly selected four transcripts illustrating a range of regions and years in practice. Iterative deliberation yielded team consensus about coding discrepancies, emergent codes, and amended coding descriptions. The qualitative team applied the final codebook to the remaining transcripts. In a second stage, using NVivo (version 11, QSR International), codes were organized into themes through a consensus process using pattern and focused coding to capture the range and variability of subthemes and to characterize both confirmatory and contradictory narratives.26,28 Study reporting reflects Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (COREQ) 25.

Results

Interview Participants

We completed 35 semi-structured interviews with nephrologists at 18 centers. Approximately 20% of these nephrologists were women, 66% had 10 or more years of nephrology experience, and 80% were from academic medical centers. Mean interview time was 36.3 ± 10.9 (standard deviation) minutes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristic | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 28 (80) |

| Female | 7 (20) |

| Time since completed nephrology training | |

| 0–5 y | 7 (20) |

| 6–10 y | 5 (14) |

| >10 y | 23 (66) |

| STATE | |

| ARIZONA | 2 (6) |

| CALIFORNIA | 2 (6) |

| FLORIDA | 2 (6) |

| MAINE | 3 (9) |

| MARYLAND | 5 (14) |

| MASSACHUSETTS | 13 (37) |

| NEW JERSEY | 2 (6) |

| NEW MEXICO | 4 (11) |

| PENNSYLVANIA | 2 (6) |

| DIALYSIS FACILITY MEDICAL DIRECTOR | 18 (51) |

| Practice type | |

| Large Academic | 24 (69) |

| Small Academic | 4 (11) |

| Community | 7 (20) |

Note: N=35.

Box 1 shows differences in factors influencing whether and how nephrologists integrate CM into care conversations between nephrologists who routinely discuss CM and those who do not. Only one-third of participants (hereafter “early adopters”) routinely discussed CM. Most nephrologists opted not to present CM neutrally as a legitimate alternative to dialysis. Participants noted that awareness of CM has increased but discussion remained infrequent.

Box 1. Factors associated with nephrologists’ decisions to discuss conservative management.

| CM Discussions Routinely Included in Care Conversations | |

|

|

| “Every patient (I think is …required by regulation), is informed that they have four choices: hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, transplantation, and conservative management.” (Participant ID 59, female, >10 years in practice) “Our practice is a little unusual in that we have a CKD care manager here who is full time in the practice and that person helps us with discussing treatment options with the patients. I’ve always been very …proactive about conservative management, so talking to patients who might not want dialysis or might not be good candidates for dialysis.” (Participant ID 63, male, >10 years in practice) | |

| CM Discussions Included ONLY When Triggered | |

|

|

| “Some patients who are very debilitated, I am more aggressive at talking to them about palliative care. They’re learning what they expect from dialysis. I start the decision by saying, ‘Want to do dialysis? What do you expect to get out of it?’ Especially in someone who’s having other health problems cause majority of times dialysis does not improve their health.” (Participant ID 86, male, >10 years in practice) “Everyone comes into this from a different background and some of the elderly people who have a lot of comorbid conditions, I would tell them there’s an option to even not do dialysis if they’re very frail and coming from a nursing home or something like that. That’s something that I want to discuss with them and their families and get their opinion on that.” (Participant ID 21, male, >10 years in practice) | |

| CM Discussions Not Integrated in Usual Care | |

|

|

| “Rarely would we say that we don’t think [dialysis is] possible.” (Participant ID 7, male, >10 years in practice ) “I won’t really offer it [CM], but the way I’ll bring it up, I’ll say, ‘You know at some point where we’re heading your kidney function will go down to basically zero and that point in order to keep you alive we have to replace the kidney function. So we have the option of always sort of not doing that, but these are the options we have for replacing your kidney function.’ I’m not putting conservative therapy up at the forefront when I’m offering these treatments. I guess after offering them these different options that we have for treatment, if they then sort of don’t want any of them and want conservative management then I would sort of go down that route and discuss with them what that means, that decision to make sure that they understand.” (Participant ID 19, male, 0–5 years in practice) | |

Note: This box clarifies barriers and facilitators common among nephrologists who approach engaging with CM conversations similarly (routinely discuss CM, disscuss CM when triggered, seldom discuss CM). These factors, which follow from the thematic analysis, were prominent in nephrologists’ propensity to discuss CM as well as their approach to CM conversations. The table includes illustrative quotations to demonstrate how these factors were discussed in interviews.

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; CM, conservative management; ID, study identification number.

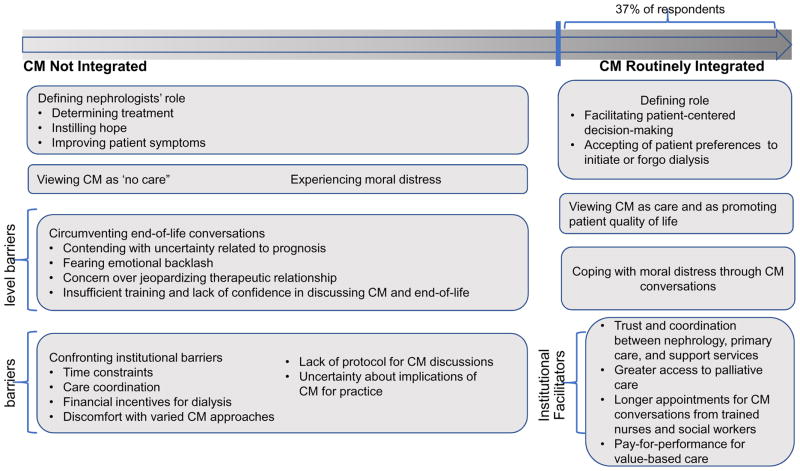

We found limited evidence of center-level effects leading nephrologists at the same institution to discuss CM similarly. Of 9 centers with multiple participants, 4 sites displayed a clustering of nephrologists who always discussed CM; at other centers, CM approaches diverged, with at least one “early adopter” at half the centers. Figure 1 displays the five themes and respective subthemes reflecting barriers and facilitators to discussions about CM, and also factors affecting the nature of these discussions when they occur.

Figure 1. Factors influencing nephrologists’ decisions to discuss conservative management (CM).

This figure presents the spectrum of integration of CM into care discussions, spanning from no integration of CM to routine integration of CM. The boxes in the figure are derived from the thematic analysis, and convey barriers and facilitators affecting nephrologists’ decision to present CM, and factors affecting how they approach care discussions.

Themes and Subthemes

Struggling to Define Nephrologists’ Role

Emergent subthemes clarified how differing role perceptions dissuaded some from presenting CM fully and led many to “shield” patients from prognosis.

Determining Treatment: Nephrologist Role vs Patient Autonomy

Many nephrologists derived confidence from longstanding relationships with patients and perceived treatment selection as their primary role. Some were dismissive of patient preferences, viewing patients as uninformed about the realities of dialysis or as simply not wanting to try. One said, “You just develop a rapport and you just know … to the point where I was like, ‘No, this is bad. You’re going [to dialysis] now, no ifs ands or buts, done.’” Another noted, “I wouldn’t say that I present [options] neutrally for them to make a decision … because my own bias is that the [patients] that I’m presenting [dialysis] to are generally the ones that I think it would be beneficial.” Others struggled and tried to honor patient preferences only after their preference (usually hemodialysis) was declined. Conversely, for some the approach was driven primarily by patient preferences: “There are times the patients are not willing to make a decision and, as a patient, they have a right … because that’s their life and if they do not want to decide what they want to do with ESRD is imminent, they can do that.”

Instilling Hope

Nephrologists viewed preserving hope as a central role and as justification to omit CM as an option. Nephrologists’ hopefulness and optimism abounded, with many stating that their patients “did better than average on dialysis”. Participants focused on salient cases where patients felt better after dialysis. One remarked, “I view myself as someone who tries to provide a ray of hope for people who are sick… I’ve seen enough people who feel so much better [after dialysis]”. Fearful that presenting CM may discourage patients from trying dialysis, many acted to preserve hope and chose not to convey all options.

Improving Patient Symptoms

Typical conversations focused on the benefits of dialysis for symptom management and potential longevity, generally omitting CM as an alternative. These factors and a duty to initiate dialysis guided many nephrologists, even those initially inclined towards CM. “I let her go six months because she didn’t really exhibit symptoms; she’s like ‘I feel fine’. Then one day she walked in and I said, ‘That’s enough. I’ve given you your time and I think now we have to get you in [to dialysis].’” Many nephrologists considered CM as an option, even if they decided ultimately not to present this option to patients.

Circumventing End-of-Life Conversations

Most nephrologists focused on active treatments, obscuring the terminal nature of CKD. Significant physician-level barriers to discussing CM included fear of withholding beneficial treatment, prognostic uncertainty, and reluctance to upset patients. Trepidation about patients’ emotional responses impeded discussions of goals of care and quality of life.

Contending With Uncertain Prognosis

Uncertainty led many to avoid communicating prognosis. “I would argue that most physicians don’t …go over this with the patient.” Another said, “I don’t know the answer to prognosis questions. I actually don’t address prognosis.” The difficulty of “not knowing how long [patients will] live on dialysis” led many to avoid discussing CM. “We are really, as a profession… so terrible at prognosis… To some extent it’s false optimism and realistic optimism and unwillingness to face death … also the realization that we’re just so terrible at predicting the future.”

Fearing Emotional Backlash

Nephrologists expressed reluctance to upset patients, feeling unprepared and concerned over “patients shutting down”. “I feel that it’s a failure when people just respond to me with anxiety… or anger and I’m not able to help them deal with that … and I’m just throwing up my hands and saying: this is just going to happen, they’re going to come into the emergency room in crisis and we’ll deal with it then.”

Jeopardizing Longstanding Relationships

Nephrologists were keen to preserve and protect relationships with patients, having cultivated trust over time. Many described a sense of failure when patients did not pursue dialysis. Some avoided discussing CM fearing that this would raise suspicions or result in patients “shopping around”: “I think that patients are always sort of suspicious [of] physicians. I think that patients want to get as much as they can out of their medical care, and when a physician says dialysis may not be right for you, they don’t believe that.”

Tailoring Information to Specific Populations

Participants tailored information about CM, citing distrust, language, or family barriers as challenges for some populations. Although sensitive to varying cultural preferences, nephrologists were often shaped by personal experience rather than expressed patient preferences. One said, “There are cultural prohibitions against discussing certain things.” When probed about their beliefs, some noted that more evidence is needed and better decisional support.

Confronting Institutional Barriers

Institutional barriers reinforced physician-level barriers, dissuading many from even describing CM.

Coping With Time Constraints

Brief clinic visits constrained nephrologists’ ability to engage patients. “We … talk about quality of life to the patients, we try to gauge what is important for them, but I do believe we do a poor job because of the limits of time….” Participants focused on “active next steps”, including referrals to vascular surgery, nursing, or dialysis classes and describing dialysis modalities but not comparing dialysis to CM.

Attempting Care Coordination

Lack of care coordination hindered attempts at conservative management. Many described a need for palliative care consults and physician extenders (e.g. social workers) and viewed a “team approach” as critical: “[CM] does take some collaboration between us and primary doctors and other supports…We as a nephrology division can’t do [CM] on our own …without any of those additional services to help out.”

Established relationships with other services, trust, communication, and shared documentation in integrated health systems were key to successful CM. Many nephrologists felt alone when patients opted for CM, unsupported by their practice or healthcare system, unsure how to proceed, and concerned about the logistical feasibility of implementing CM.

Incentivizing Dialysis

Some acknowledged the financial incentives for dialysis and were concerned with the economic viability of CM. “The economic side is always important, as a practitioner, so obviously the division [is] sustain[ed] on the revenue generated… from the dialysis unit.” Many thought financial incentives affected their colleagues’ behavior, but were less certain about implications for their own process.

Discomfort With Varied Conservative Management Approaches

Lack of systematic training was seen as a key reason for variation in attitudes and approaches to CM, even within a practice. “I think there are … a lot of differences among doctors even in our practice …there’s still that kind of range of comfort levels.” Some felt their colleagues’ discomfort discussing CM deprived some patients of this option: “We do discuss non-dialytic approaches to CKD 5; however I think that there’s huge variability in who really lays that out for them. [Some] don’t seem to either believe in it, or they don’t feel comfortable in approaching that topic and opening up that level of discussion, which is again, you know just a lack of uniformity in the way we approach some … patients.”

Even among nephrologists championing CM, lack of a supportive culture and uniformity in CM approaches led to hesitation. When seeing patients in the hospital, few knew whether patients were informed about CM and were hesitant to disclose new options.

Conservative Management as “No Care”

Many perceived CM as not providing care: “The thought that conservative care is no treatment is a (stopping) point for conservative care. It sort of feels like… feels like giving up.” Having “nothing to offer” conflicted with nephrologists’ perceptions of their role, and also posed a challenge to presenting CM fairly. Most wanted to offer patients an active option, viewing this as more palatable to patients. They equated active therapy with hope, and passive therapy (CM) with failure or “giving up”. Although many knew that CM and dialysis can offer similar survival for elderly patients, nephrologists equated CM with a certain death: “[We are] comfortable ourselves with the fact that we’re in the business of combatting death. But we need to become [better] with the business of accepting death, that we have limits… Clearly oncologists do this better than nephrologists, and ultimately palliative care consultants do this best.”

Experiencing Moral Distress as Catalyst for Conservative Management

Moral distress occurs when clinicians are aware of a moral problem and perceive a responsibility to act, yet because of institutional constraints, cannot act in a way consistent with their moral judgments. Response to moral distress distinguished “early adopters” from others. It catalyzed them and increased their vigilance in discussing CM routinely, even when facing more challenging patients. Early adopters noted that universally offering CM relieved moral distress, whereas nephrologists who only sometimes offered CM continued to experience significant distress (Box 1).

The futility of dialysis for older, sicker patients troubled many interviewed nephrologists; they described distress watching patients die in pain, hospitalized, and dialyzed against their wishes. One early adopter said, “I’ve noticed with several of my older colleagues that we have far less trouble in saying, ‘This is enough…there’s no quality of life here, there’s no chance of any meaningful recovery, why are we flogging this poor person?’ Whereas my younger colleagues are fighting to the bitter end.” Differences of opinion often divided colleagues, and participants were distressed by this too. Early adopters focused on reducing suffering near death, preserving patient dignity, and recognizing medical futility. Early adopters found solace in conversations about CM, even if patients ultimately chose dialysis: “I have become more respectful of the notion that a few more days or a few more months might be meaningful to people. So it hasn’t made me more eager to do intrusive and painful things to frail old people, but it’s made me feel less guilty and less passionate and less angry when they demand it.”

Many also described frustration when family members overturn patient preferences for CM, and felt unable to resolve these conflicts. One recalled, “That’s happened a number of times… the patient may decide on their own that they don’t want dialysis at all and then … the family [will] ultimately be the ones that will push the patient to a sort of more aggressive approach than what was originally proposed.”

Discussion

We found that care discussions with older patients with CKD do not routinely include the topic of CM. Discussion ranged from presenting CM as a comparable alternative to dialysis to omitting it entirely. Nephrologists’ approach to discussions about CM was largely shaped by perceptions of their role and by a common view of CM as “no care”; their willingness to pursue CM is influenced by provider-level and institutional-level barriers and personal experience with moral distress. Expanding on prior quantitative findings, we clarify how moral distress serves as a catalyst for discussion of CM and highlight points of intervention and mechanisms potentially underlying low CM use in the United States.7,12,29

Over the past decade, clinical guidelines and studies about CM have increased.4,7,9,12,29–33 For example, the Renal Physicians Association published evidence-based guidelines describing best practices related to forgoing and withdrawing from dialysis.34 These practices include shared decision-making, fully informing patients about all treatment options, providing patients with realistic prognosis estimates, facilitating advanced directives, forgoing dialysis when appropriate, and providing effective palliative care. Efforts to achieve consensus among nephrologists about their role in discussing end-of-life and CM are crucial to improve widespread adoption of CM.

Perceptions of CM as “no care”, concern about upsetting patients, and lack of institutional support for CM deter many nephrologists from presenting CM as an option. Patients and physicians alike commonly prefer treatments framed as active rather than passive. 35,36 Oncologists have effectively rebranded clinical approaches to mitigate this bias, e.g., performing “active surveillance” rather than “watchful waiting” of diagnosed but untreated prostate cancer. In the CKD context, rebranding CM as “active medical management” or “comprehensive supportive care” may help reframe this discussion, allowing nephrologists and patients to feel more comfortable choosing CM. Standardizing the timing of follow-up visits and formalizing services available to patients (e.g. nutrition, palliative care, psychology, social work) may further support nephrologists in presenting and providing CM. Clarifying the population of patients in need of discussions about CM and fully incorporating CM into the “options” or educational classes could also help implement CM. Additionally, sometimes patients opting for active surveillance may experience greater uncertainty and anxiety, and nephrologists should be prepared to revisit the decision periodically and engage psychosocial experts when needed.37,38

It is equally important to ensure that documented preferences for CM are clear and accessible to providers across care settings. Ensuring documentation in electronic medical records and completing forms such as the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) are needed first steps. Furthermore, nephrologists expressed concern that families, often adult children, override patients’ choice of CM. Identifying a medical proxy and including the proxy in early conversations could help ensure that patient wishes are respected.19 Nephrologists should also be aware of the high prevalence of limited health literacy among patients with CKD and account for this when discussing CM and end-of-life care.18

The aging of the population with advanced CKD in the United States increasingly requires nephrologists to participate in end-of-life care decisions for older adults. However, we found nephrologists still to feel unprepared and to want more training in shared decision-making, specifically around end-of-life decisions.39,40 Most nephrologists also avoided discussing prognosis, despite studies finding that patients desire prognostic information, however dire their circumstance.9 Future studies should also focus on developing and testing culturally sensitive materials tailored to meet the needs and preferences of underserved populations who may approach end-of-life care differently. Decision aids may also facilitate shared decision-making and CM discussions.33

We found that “early adopters” of CM engaged in more patient-centered discussions, articulating the benefits and drawbacks of dialysis and CM, allowing for patient engagement. This approach was bolstered by a nuanced perception of the nephrologists’ role as facilitating decision-making and managing patient symptoms in a way that aligned with their patient’s lifestyle goals. Early adopters attributed their resiliency to moral distress to their patient-centered approach and routine discussions of CM, which mostly alleviated their concerns over futile care. Nephrologists who only sometimes discussed CM were more sensitive to moral distress, voicing concern over identifying appropriate patients for discussions of CM. Routinely discussing CM with patients older than 75 years may alleviate this distress, unify the approach among providers, and strengthen support among colleagues with common challenges.

Half of the sites had “early adopters”. Given the recent increased attention to CM, these ‘early adopters’ may serve a crucial role as physician champions of CM and be a resource to their colleagues. Considerable evidence underscores the importance of physician champions for adoption of clinical innovations, including in advance care planning.41,42 Our findings suggest that the common experience of moral distress may serve to catalyze “early adopters” to discuss CM, and establish shared experiences and illustrate its value to nephrologists hesitant to change their practice. Greater institutional acceptance of and support for CM would also help to normalize it, allowing for nephrologists to more candidly and openly discuss CM as part of care plans and address barriers. Lastly, financial support for these provider and infrastructure efforts would reduce another barrier.

The strengths of our study include purposively sampling across multiple states, including a diverse sample (years of practice, sex, practice setting), and examining incenter and between-center variation. Limitations include over-sampling of academic medical centers. Our findings are transferable to a broad population of older patients in the United States faced with choosing between CM and dialysis, many of whom do not perceive a choice because they are uninformed about CM.9 Our study provides a framework for understanding how nephrologists approach discussions about CM, including how perceptions of patients (emotions, preferences, health literacy, etc.) and institutional factors may influence nephrologists’ decisions to discuss CM. Future research should examine the prevalence of CM practices and discussions, including implications for workflow, involvement of other specialties (e.g. palliative care), and patient satisfaction. Use of decision aids to empower patients and improve shared decision-making related to CM and dialysis initiation should also be evaluated.

Barriers to discussions of CM, including perceptions that patients will lose hope if told their prognosis and that CM equates to ‘no care’, should be addressed to increase nephrologists’ engagement in discussions of CM. Improved access to CM may require greater uniformity and empowering “early adopters”.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support: Dr Ladin gratefully acknowledges financial support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (award number KL2TR001063). Drs Weiner and Meyer receive indirect salary support paid through Tufts Medical Center from Dialysis Clinic Inc (DCI) and are DCI medical directors. None of the funders have had any role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Brianna Xavier for her assistance with transcribing interviews and with data management. We are extremely grateful for the generous contributions of the clinicians in participating in the study. We are also grateful to Ebony Boulware, MD, and to members of the Health Research Seminar at Tufts University for insightful comments.

Footnotes

Item S1: Interview guide.

Supplementary Material Descriptive Text for Online Delivery

Supplementary Item S1 (PDF). Interview guide.

Authors’ Contributions: Research idea and study design: KL; data acquisition: DEW, RDP, KBM, RP, AK, RL, TO; data analysis/interpretation: KL, RP, AK, RL, TO; supervision or mentorship: KL, DEW, JBW. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moist L, Port F, Orzol S, et al. Predictors of Loss of Residual Renal Function among New Dialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:556–564. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V113556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ. Comparative Survival among Older Adults with Advanced Kidney Disease Managed Conservatively Versus with Dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(4):633–640. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07510715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tam-Tham H, Thomas CM. Does the Evidence Support Conservative Management as an Alternative to Dialysis for Older Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(4):552–554. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01910216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonkin-Crine S, Okamoto I, Leydon GM, et al. Understanding by older patients of dialysis and conservative management for chronic kidney failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(3):443–450. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song MK. Quality of Life of Patients with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease Receiving Conservative Care without Dialysis. Semin Dialysis. 2016;29(2):165–169. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pacilio M, Minutolo R, Garofalo C, Liberti ME, Conte G, De Nicola L. Stage 5-CKD under nephrology care: to dialyze or not to dialyze, that is the question. J Nephrol. 2016;29(2):153–161. doi: 10.1007/s40620-015-0243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morton RL, Snelling P, Webster AC, et al. Factors influencing patient choice of dialysis versus conservative care to treat end-stage kidney disease. Can Med Assoc J. 2012;184(5):E277–283. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chanouzas D, Ng KP, Fallouh B, Baharani J. What influences patient choice of treatment modality at the pre-dialysis stage? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(4):1542–1547. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladin K, Lin N, Hahn E, Zhang G, Koch-Weser S, Weiner DE. Engagement in decision-making and patient satisfaction: a qualitative study of older patients’ perceptions of dialysis initiation and modality decisions. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(8):1394–1401. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA. Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(4):495–503. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195–204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parvez S, Abdel-Kader K, Pankratz VS, Song MK, Unruh M. Provider Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Surrounding Conservative Management for Patients with Advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):812–820. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07180715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA. System-Level Barriers and Facilitators for Foregoing or Withdrawing Dialysis: A Qualitative Study of Nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.015. S0272-6386(17)30116-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison SN, Torgunrud C. The creation of an advance care planning process for patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49(1):27–36. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luckett T, Sellars M, Tieman J, et al. Advance care planning for adults with CKD: a systematic integrative review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):761–770. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray MA, Brunier G, Chung JO, et al. A systematic review of factors influencing decision-making in adults living with chronic kidney disease. Patient Educ Counsel. 2009;76(2):149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine. DYING IN AMERICA: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladin K, Buttafarro K, Hahn E, Koch-Weser S, Weiner DE. “End-of-Life Care? I’m not Going to Worry About That Yet.” Health Literacy Gaps and End-of-Life Planning Among Elderly Dialysis Patients. Gerontologist. 2017 Mar 10; doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw267. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renal Physicians Association. Shared Decision Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis. 2. Rockville, MD: Renal Physicians Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A, Cheung KL, Nair SS, Kurella Tamura M, Craig JC, Winkelmayer WC. Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies on patient and caregiver perspectives on end-of-life care in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(6):913–927. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurella Tamura M, Goldstein M, Perez-Stable E. Preferences for dialysis withdrawal and engagement in advance care planning within a diverse sample of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(1):237–242. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Da Silva-Gane M, Farrington K. Supportive care in advanced kidney disease: patient attitudes and expectations. Ren Care. 2014;40(Suppl 1):30–35. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1206–1214. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Holley JL, Moss AH. Nephrologists’ reported preparedness for end-of-life decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1256–1262. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02040606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chase S. Narrative Inquiry: Multiple lenses, approaches and voices. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saldaña J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Vol. 14. SAGE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morton RL, Turner RM, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC. Patients who plan for conservative care rather than dialysis: a national observational study in Australia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(3):419–427. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemmelgarn BR, Pannu N, Ahmed SB, et al. Determining the research priorities for patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;2(5):47–854. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thamer M, Kaufman JS, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Cotter DJ, Bang H. Predicting Early Death Among Elderly Dialysis Patients: Development and Validation of a Risk Score to Assist Shared Decision Making for Dialysis Initiation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(6):1024–1032. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, et al. Advance Care Planning and End-of-Life Decision Making in Dialysis: A Randomized Controlled Trial Targeting Patients and Their Surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):813–22. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladin K, Weiner DE. Better informing older patients with kidney failure in an era of patient-centered care. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(3):372–374. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renal Physicians Association. Shared Decision Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, 2nd Edition. Rockville, MD: Renal Physcians Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croskerry P. Achieving Quality in Clinical Decision Making: Cognitive Strategies and Detection of Bias. Acad Emer Med. 2002;9(11):1184–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugarman D. Active versus passive euthanasia: an attributional analysis. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1986;16(1):60–76. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davison BJ, Breckon E. Factors influencing treatment decision making and information preferences of prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(3):369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor KL, Hoffman RM, Davis KM, et al. Treatment Preferences for Active Surveillance versus Active Treatment among Men with Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(8):1240–1250. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holley JL, Carmody SS, Moss AH, et al. The need for end-of-life care training in nephrology: national survey results of nephrology fellows. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(4):813–820. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Combs SA, Culp S, Matlock DD, Kutner JS, Holley JL, Moss AH. Update on end-of-life care training during nephrology fellowship: a cross-sectional national survey of fellows. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(2):233–239. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaw EK, Howard J, West DR, et al. The role of the champion in primary care change efforts: from the State Networks of Colorado Ambulatory Practices and Partners (SNOCAP) J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):676–685. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.110281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, O’Leary JR. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1547–1555. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.