Abstract

Rationale:

Atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) remains a difficult diagnosis despite advances in imaging technologies. This is a case study of the diagnostic and treatment course for a patient with AKC.

Patient concerns:

A 15-year-old male complained of progressively increasing pain, redness, watering and blurred vision in the right eye. The medical history showed that the patient suffered from itching on the hands, knees, neck and the eye skin one year before the onset of initial symptoms in the affected eye.

Diagnoses:

A final diagnosis of stage III AKC with atopic dermatitis (AD) was reached.

Interventions:

The patient was used 0.1% tacrolimus eye drops and 0.3% gatifloxacin eye gel after antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed. In the presence of AD, 0.1% mometasone furoate cream and 0.03% tacrolimus ointment were applied twice daily.

Outcomes:

One month after starting treatment, the conjunctivitis and corneal ulcer rapidly improved along with reduced lid papillae. Macular grade corneal opacity was noticed with minimal thinning. The AD also rapidly improved. At the end of two months patient was asymptomatic with a significant improvement in his quality of life.

Lessons:

Proper diagnosis of AKC especially when associated with dermatological signs along with management of AD in conjunction with dermatologist is necessary to prevent corneal involvement which can cause permanent visual disability is of utmost importance. We also noticed that topical tacrolimus is a good option for the treatment of severe AKC with AD along with systemic immunosupressants.

Keywords: atopic dermatitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis, tacrolimus

1. Introduction

In 1953, Hogan described a chronic allergic eye disease—atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC)—which although rare can have serious consequences.[1] AKC has been described as a noninfectious chronic inflammatory ocular-surface condition associated with other atopic conditions. AKC can present along with the onset or course of associated atopy, although the severities of both conditions may differ along with the involvement of the cornea.[2] Corneal involvement can progress to frank epithelial erosion, ulceration, formation of mucous plaques, and epithelial filaments.[3] Moreover, corneal scarring and neovascularization from persistent inflammation can occur, possibly leading to vision loss. Therefore, prompt and effective treatment is required.

We herein report a case of AKC (first misdiagnosed as viral stromal keratitis) in a 15-year-old male. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee at the Beijing Tongren Hospital (Beijing, China). Written informed consent for publishing the clinical details and images was obtained from the patient.

2. Case history

A 15-year-old male presented to our hospital complained of progressively increasing pain, redness, and watering (epiphora) in the right eye beginning 15 days previously. As he developed blurred vision in the same eye during the last 5 days, he underwent an ocular examination elsewhere where he was diagnosed with viral stromal keratitis and prescribed topical antivirals (ganciclovir eye drops 3 times a day in the right eye). However, the patient's symptoms did not resolve, instead they worsened. He was then referred to our hospital for further management.

The medical history showed that the patient suffered from itching on the hands, knees, neck, and the eye skin 1 year before the onset of initial symptoms in the affected eye. The itchiness was almost gone after 3 months of herbals treatment. One month before the onset, he presented with skin itching again, and the symptoms did not response when treated with the same herbs.

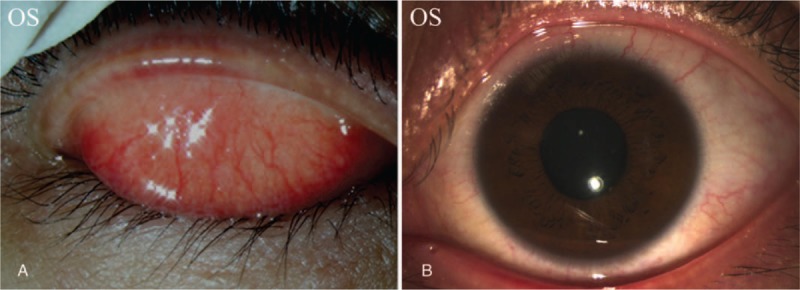

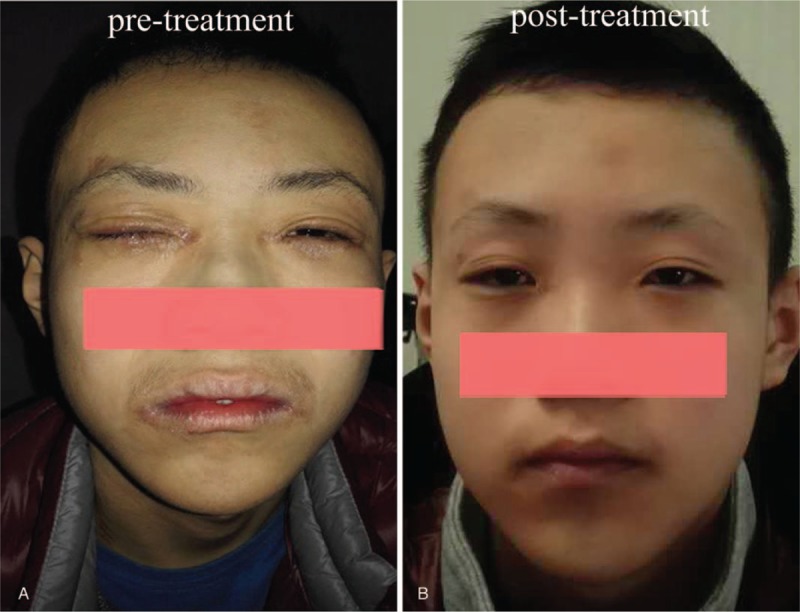

Slit lamp examination of the right eye showed a thickened and inflamed eyelid margin with fissuring and hyperpigmentation, conjunctival giant papillary hypertrophy, obscured palpebral conjunctival vessels, and mucoid discharge (Fig. 1A). We also observed diffuse superficial conjunctival congestion, gelatinous hyperplasia at the superior limbus (Fig. 2A, red arrow), and a shield ulcer in the inferior cornea measuring approximately 6 mm × 3 mm (Fig. 2A, black arrow). The superior of the shield ulcer showed dense multifocal anterior stromal infiltrate accompanied with necrotic tissue (Fig. 2A, yellow arrow). No anterior chamber reaction was noticed. A fundus examination was deferred due to photophobia. No obvious abnormality was found in the left eye (Fig. 3), except the eyelid. Focal areas of dermatitis were found in the right periorbital area, lips, and neck. Dermatitis on the left lower eyelid was also found (Fig. 4A). The patient was referred to a dermatologist who diagnosed atopic dermatitis (AD).

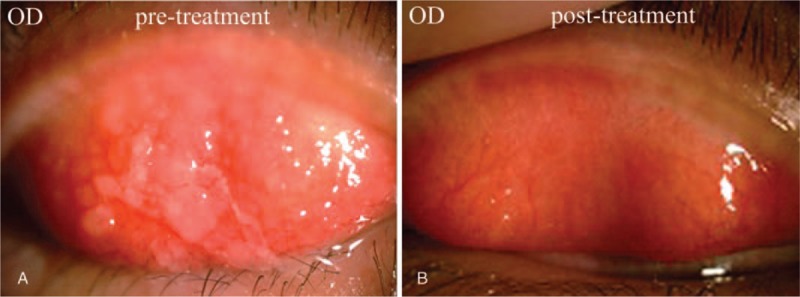

Figure 1.

(A) Conjunctival giant papillary hypertrophy, thickening, palpebral conjunctival vessels obscured and mucoid/ropy discharge. (B) Resolution of conjunctival giant papillae following treatment.

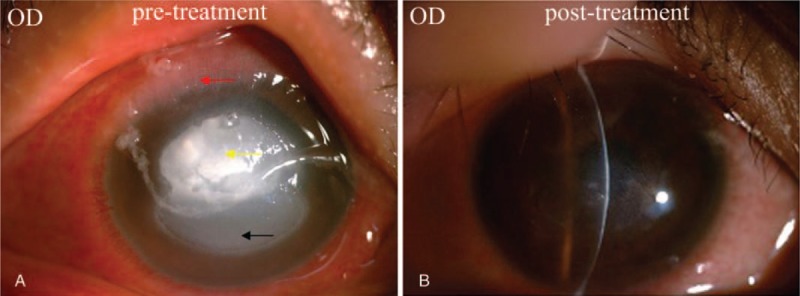

Figure 2.

(A) Diffuse superficial conjunctival congestion, gelatinous hyperplasia at the superior limbus (red arrow), shield ulcer in the inferior cornea (black arrow). The superior of the shield ulcer showed dense multifocal anterior stromal infiltrate accompanied with necrotic tissue (yellow arrow). (B) Nebulomacular corneal scar postresolution.

Figure 3.

(A) Palpebral conjunctiva. (B) Bulbar conjunctiva and cornea.

Figure 4.

(A) Atopic dermatitis at the periorbital, around the lips and neck. (B) Resolution of atopic dermatitis following treatment.

Corneal scrapping was done and Grams stain showed a large number of cocci, occasional epithelial cells, and a few inflammatory cells. Staphylococcus aureus was identified through bacterial culture, and drug sensitivity tests determined that gatifloxacin was more effective than other antibiotics. Further corneal scraping for fungal culture was negative. A final diagnosis of stage III AKC with AD was reached.

The patient was started on 0.1% tacrolimus eye drops. Initially, 0.5% levofloxacin eye drops was applied to the patient for 7 days (3 times/day) and then changed to 0.3% gatifloxacin eye gel after antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed. In the presence of AD, 0.1% mometasone furoate cream and 0.03% tacrolimus ointment were applied twice daily. Systemic treatment (fexofenadine hydrochloride tablet twice a day and cetirizine hydrochloride tablet once at night) was prescribed as per the dermatologist's instruction.

One month after starting treatment, the conjunctivitis and corneal ulcer rapidly improved along with reduced lid papillae, as determined by slit-lamp examination. Macular grade corneal opacity was noticed with minimal thinning (Figs. 1B and 2B). The AD also rapidly improved (Fig. 4B). Treatment was gradually tapered over a period of 2 months after which time the patient was asymptomatic with a significant improvement in his quality of life. No adverse effects of treatment were noticed throughout his health care at our hospital.

3. Discussion

Both AD and AKC are manifestations of atopy. AKC is associated with AD in 95% of cases.[4] Conversely, only 20% to 43% of patients with AD have ocular involvement.[2] Patients with AD (similar to those with AKC due to their reduced innate immunity) are more susceptible to infections. Several reports of staphylococcal and herpes simplex infections of the skin and eyes have been published.[5] Similarly, we noticed that our patient developed a secondary staphylococcal bacterial corneal ulcer following development of a shield ulcer, which resolved with use of topical antibiotics.

AKC is a complex chronic inflammatory disease of the ocular surface. Both conjunctival epithelial cells and inflammatory cells infiltrating conjunctival tissues (eosinophils, T lymphocytes, mast cells, and basophils) are responsible for the secretion of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines that induce progressive remodeling of the conjunctival connective tissue—leading to mucus metaplasia, conjunctival thickening, neovascularization, and scarring. These physiological mechanisms are responsible for the pathogenesis of corneal complications seen in vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC).[6]

AKC typically presents in the second or third decade and may continue up to the fifth decade of life, although in rare cases may present in childhood or in the adults in their late 50s.[3] Clinical expression of AKC involves conjunctiva, eyelids, and cornea, with a wide spectrum of symptoms such as intense itching, epiphora, redness, and loss of vision.[7] Different from the infectious eye diseases which can affect only 1 eye, AKC is caused by “atopy,” a genetic condition, it is generally reported by bilateral symptoms. However, we noticed only unilateral involvement in our patient, which may have led to the misdiagnosis. This patient was initially misdiagnosed as viral stromal keratitis due to the deceptive symptoms, including the unilateral onset, corneal ulcer with infiltration into corneal storm as well as the secondary bacterial infection. However, this patient did not respond to antiviral therapy. Also, giant papillary conjunctivitis, gelatinous limbal hyperplasia, shield ulcer, especially the atopic dermatitis occurred in this patient, which were the typically indicators for the differential diagnosis. Generally, the differential diagnosis for AKC also includes: VKC, which has similar symptoms with AKC and often occurs in patients less than 20 years of age, but the patient developed in winter and was associated with atopic dermatitis; and seasonal allergic conjunctivitis, which was seasonal (caused by allergens like pollen) or perennial (caused by allergens like dust mites or animal hair) ocular allergy, but does not affect the cornea.

Topical antihistamines combined with mast cell stabilizers are the cornerstone of ocular allergy treatment, but more aggressive treatments such as administrations with topical or systemic immunosuppressive drugs (steroids, tacrolimus, and cyclosporin A) may be required in the most severe forms of disease.[8]

Tacrolimus, a competitive calcineurin inhibitor and macrolide antibiotic isolated from the soil fungus species Streptomyces tsukubaensis, is commonly used in the management of ocular allergy. Tacrolimus primarily acts by downregulating the activity of T cells and hence reduces inflammation. It also acts as competitive antagonist by binding to steroid receptors on the cell surface, inhibiting the release of mediators from mast cells, regulating the number of interleukin 8 receptors, and decreasing the intracellular adhesion and the expression of E-selectin in blood vessels. All of these actions result in reduced recognition of antigens and in regulation of the inflammatory cascade.[9] In this sense, tacrolimus is 10 to 100 times more potent than cyclosporine. One of the common side effects with topical tacrolimus ointment is a stinging sensation on application, however this is known to reduce or subside after 2 to 4 weeks of continued use. Various reports on the successful use of tacrolimus for ocular and cutaneous conditions have been published.[10] We also noticed that our patient responded well to topical tacrolimus ointment.

In summary, a correct diagnosis of AKC is important (especially when it is associated with dermatological signs) to prevent corneal involvement which can lead to permanent visual disability in the absence of suitable treatment. It is also necessary to consult with a dermatologist during management of AD. We noticed that topical tacrolimus plus systemic immunosupressants is a good option for the treatment of severe AKC with AD.

Author contributions

Funding acquisition: ying jie.

Supervision: ying jie.

Data curation: Ai peng Li, Shang Li.

Writing – original draft: Ai peng Li.

Project administration: Shang Li.

Resources: Fang Ruan.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AD = atopic dermatitis, AKC = atopic keratoconjunctivitis, VKC = vernal keratoconjunctivitis.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Rachdan D, Anijeet DR, Shah S. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis: present day diagnosis. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:1361–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Guglielmetti S, Dart JK, Calder V. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;10:478–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chen JJ, Applebaum DS, Sun GS, et al. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:569–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bielory B, Bielory L. Atopic dermatitis and keratoconjunctivitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2010;30:323–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Baker BS. The role of microorganisms in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Immunol 2006;144:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Offiah I, Calder VL. Immune mechanisms in allergic eye diseases: what is new? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;9:477–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Leonard JN, Dart JK. Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. Wiley-Blackwell, 8th ednOxford:2010. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brémond-Gignac D, Nischal KK, Mortemousque B, et al. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis in children: clinical features and diagnosis. Ophthalmology 2016;123:435–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].García DP, Alperte JI, Cristóbal JA, et al. Topical tacrolimus ointment for treatment of intractable atopic keratoconjunctivitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cornea 2011;30:462–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Westland T, de Bruin-Weller MS, Van der Lelij A. Treatment of atopic keratoconjunctivitis in patients with atopic dermatitis: is ocular application of tacrolimus an option? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:1187–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]