Abstract

Background

Improvements in executive functioning (EF) may lead to improved quality of life and lessened functional impairment for children with mood disorders. The aim was to assess the impact of omega-3 supplementation (Ω3) and psychoeducational psychotherapy (PEP), each alone and in combination, on EF in youth with mood disorders. We completed secondary analyses of two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of Ω3 and PEP for children with depression and bipolar disorder.

Methods

Ninety-five youth with depression or bipolar disorder-not otherwise specified/cyclothymic disorder were randomized in 12-week RCTs. Two capsules (Ω3 or placebo) were given twice daily (1.87g Ω3 total daily, mostly eicosapentaenoic acid). Families randomized to PEP participated in twice-weekly 50-minute sessions. Analyses assess impact of interventions on the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning (BRIEF) parent-report Global Executive Composite (GEC) and two subscales, Behavior Regulation (BRI) and Metacognition (MI) Indices. Intent-to-treat repeated measures ANOVAs, using multiple imputation for missing data, included all 95 randomized participants. Trials were registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01341925 & NCT01507753.

Results

Participants receiving Ω3 (aggregating combined and monotherapy) improved significantly more than aggregated placebo on GEC (p=0.001, d=0.70), BRI (p=0.004, d=0.49), and MI (p=0.04, d=0.41). Ω3 alone (d=0.49) and combined with PEP (d=0.67) each surpassed placebo on GEC. Moderation by ADHD comorbidity was non-significant although those with ADHD showed nominally greater gains. PEP monotherapy had negligible effect.

Conclusions

Decreased impairment in EF was associated with Ω3 supplementation in youth with mood disorders. Research examining causal associations of Ω3, EF, and mood symptoms is warranted.

Keywords: school children, depression, bipolar disorder, psychotherapy, nutrition

Introduction

Executive function (EF) refers to regulation and modification of cognitive subprocesses (Miyake et al., 2000). EF and intellectual ability, while related, are independent constructs; EF impairments can occur without gross intellectual impairment. EF includes attention, shifting between mental sets or tasks, updating and monitoring working memory, planning, inhibiting distractions and interfering impulses, and verbal fluency (Pennington, Bennetto, McAleer, & Roberts, 1996; Welsh, Pennington, & Groisser, 1991).

EF impairments are transdiagnostic. They have been documented in mood disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), psychosis, and some anxiety disorders. In fact, many executive functions are research-domain criteria (RDoC) variables (NIMH-defined functions/pathologies that cut across diagnoses (Insel et al., 2010)). Children with major depressive disorder (MDD) demonstrate EF impairments related to academic performance, low self-esteem, and psychosocial failure (Brooks, Iverson, Sherman, & Roberge, 2010; Favre et al., 2009). EF impairments may contribute to early-onset bipolar disorders, conferring increased risk of suicide and substance abuse (Birmaher, 2007). Meta-analysis of EF in youth MDD indicated impaired inhibitory capacity (d=0.77), phonemic verbal fluency (d=0.76), working memory (d=0.49), planning (d=0.51), and cognitive-shifting ability (d=0.44) relative to healthy controls (Wagner, Muller, Helmreich, Huss, & Tadic, 2015). Meta-analysis of youth bipolar disorder revealed significant impairment relative to healthy controls on planning, organization, response inhibition, and set-shifting (d=0.55), working memory (d=0.60), and verbal fluency (d=0.45) (Joseph, Frazier, Youngstrom, & Soares, 2008). Inhibitory control, verbal fluency, and cognitive-set shifting are especially impaired in youth with MDD (Han et al., 2015; Kyte, Goodyer, & Sahakian, 2005).

Controversy exists regarding whether EF impairments are cause or effect of mood symptoms (Castaneda, Tuulio-Henriksson, Marttunen, Suvisaari, & Lonnqvist, 2008). A review depressed youths’ EF (Vilgis, Silk, & Vance, 2015) suggested EF impairments were more likely a by-product of other symptoms rather than correlates of depression development. Adult studies show increased EF impairment with greater frequency of depressive episodes, age, and melancholic symptoms (Vilgis et al., 2015; Wagner, Doering, Helmreich, Lieb, & Tadic, 2012). EF at age three years mediated the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms and children’s externalizing symptoms at age six (Roman, Ensor, & Hughes, 2016). Early exposure to maternal depression may lead to EF impairments associated with externalizing behaviors. In this case, EF impairments predate non-mood psychopathology. Although it is unclear how EF and primary depressive symptoms evolve, amelioration of one may be associated with amelioration of the other.

Ω3 supplementation trials have suggested benefit for childhood MDD and bipolar disorders (Clayton et al., 2009; Fristad et al., 2016; Fristad et al., 2015; Nemets, Nemets, Apter, Bracha, & Belmaker, 2006), working-memory improvement in young adults (Narendran, Frankle, Mason, Muldoon, & Moghaddam, 2012), and modest but significant improvement of ADHD symptoms (Chang, Su, Mondelli, & Pariante, 2017). The primary trials from which the current analyses stem demonstrated significant improvement in bipolar depression with Ω3 supplementation and small-moderate improvement in unipolar depression; there was no treatment impact on mania (Fristad et al., 2016; Fristad et al., 2015). We are unaware of studies examining impact of Ω3 supplementation on EF impairments in youth with mood disorders; there is need for such investigation.

The current analyses examined the impact of Ω3 supplementation on EF in children with mood disorders in a secondary analysis of data pooled from two identical-design randomized controlled trials (RCTs). (Primary outcomes published elsewhere reported on Ω3 supplementation and Individual Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy [PEP], alone and in combination, for treating youth mood symptoms (Fristad et al., 2016; Fristad et al., 2015).) Given the scant existing literature, this is an exploratory investigation.

Methods

Participants & Ethical Considerations

Participants were recruited primarily from community advertisements and clinician referrals within a large Midwestern city from July 2011 – May 2014. Parents provided informed consent and youth provided informed assent using procedures approved by The Ohio State University Biomedical Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were: age 7–14 years; diagnosis of DSM-IV-TR depressive disorder, cyclothymic disorder, or bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (NOS); and a caregiver willing/able to participate. Operationalization of bipolar disorder NOS was consistent with that of prior studies, Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (Birmaher et al., 2006) and the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (Findling et al., 2010): elated mood plus ≥2/irritable mood plus ≥3 associated DSM manic symptoms, clear change in functioning with impairment, duration of ≥4 hours within a 24 hour period and totaling ≥4 cumulative lifetime days, not meeting criteria for bipolar I/II disorder.

Exclusion criteria were: inability to swallow study capsules; bipolar I/II disorder (due to heightened severity of symptoms and likely need for intervention beyond scope of study); chronic medical disorder; autism; psychosis; suicidal plans or recent attempt (passive suicidal ideation without plans/intent was permitted); ≥3 “marked” or “severe” mood symptoms on the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS); pharmacotherapy (other than stable ADHD medication or sleep aid), psychotherapy, or Ω3 supplementation in the month preceding randomization; enrollment in grade ≥9; or intellectual disability.

Procedures

Screening assessment included semi-structured diagnostic interviews, administration of measures, and physical examination (see Measures). Eligible youth were randomized in a 2X2 design into one of four 12-week treatment arms: Ω3 monotherapy: n=23; PEP monotherapy (with pill placebo [PBO]): n=26; Combined intervention: n=22; or PBO (no study intervention): n=24. EF was assessed at screening and again after 12 weeks of study intervention. Trial protocols were registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01341925 and NCT01507753).

Treatments

Ω3 supplements and placebo were provided by OmegaBrite (www.omegabrite.com; Las Vegas, NV). Ω3 capsules contained 500mg (350mg EPA: 50mg DHA; 67mg other Ω3), with two capsules taken twice daily. PBO was matched with Ω3 for odor and appearance. All participants received a daily multivitamin/mineral tablet to standardize micronutrition across conditions. Adherence was monitored by pill counts from returned pill minders at each study assessment.

Participating families were encouraged to remain on stable doses of existing ADHD medications. They were not randomized if they were currently adjusting medications. Throughout the study, two children (one in PEP monotherapy; one in Ω3 monotherapy) began stimulant medication and one (assigned to combined intervention) had an upward adjustment of medication.

PEP included weekly parent and youth sessions, each lasting 45–50 minutes. Ph.D.-level therapists conducted sessions in accord with the PEP therapy manual (Fristad, Goldberg-Arnold, & Leffler, 2011). The goal of PEP is to couple psychoeducation about mood disorders and treatment with empirically supported CBT skills for mood symptoms (e.g., behavioral activation/scheduling, problem-solving, changing negative coercive family cycles via improved communication).

Randomization and Study Masking

Block randomization was not contingent on demographic variables. Separate randomization sequences were used for children with bipolar disorder versus depression. Lab personnel not directly involved in the study generated the sequences, assigned participants a number linked with a treatment condition, provided PBO/Ω3, and notified families if they were to participate in PEP.

Families, interviewers, therapists, and other study staff who had contact with families were masked regarding Ω3/PBO randomization. Families were informed whether the youth had received Ω3/PBO by sealed letter following their final assessment. Interviewers completing study assessments were masked to PEP involvement.

Measures

Demographics Form

Parents reported youths’ sex, race, ethnicity, age, family structure, and caregivers’ history of depression, ages and relationship to the youth.

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning (BRIEF) (Gioia, Isquith, Guy, & Kenworthy, 2000)

The BRIEF is a 138-item parent-report of the child’s ability to complete tasks requiring EF skills. The Global Executive Composite (GEC) is comprised of two broad subscales: Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI) and Metacognition Index (MI). BRI includes Inhibition, Shift, and Emotional Control scales. MI includes Initiation, Working Memory, Planning, Organization of Materials, and Monitoring scales. Age- and sex-normed t-scores, based on a standardization sample (N=1419) of youth, were used; higher t-scores indicate greater impairment. Test-retest reliability is excellent (GEC, 0.86; BRI, 0.84; MI, 0.88). Internal consistency was high in this sample: Cronbach’s α for GEC, 0.96; BRI, 0.90; MI, 0.95. The BRIEF was completed at screening (prior to any study intervention) and post-intervention.

Youth Diagnoses

Semi-structured interviews used to diagnose mood disorders and assess mood symptom severity included K-SADS Depression (KDRS) and Mania Rating Scales (KMRS) (Geller et al., 2001), the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R), and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS). Interviewers assessed youth separate from their parents. KDRS and KMRS allow assessment of symptoms occurring currently (last 2 weeks) in the context of a mood episode as well as worst past symptoms. CDRS-R and YMRS assess symptoms over the past 2 weeks. All interviewers were trained using both video cases and a live “expert” interviewer. Interviewer inter-rater reliability (IRR) was excellent (ICC for KDRS, 0.89; KMRS, 0.82; CDRS-R, 0.87, YMRS, 0.87).

At screening, comorbid psychiatric disorders were assessed using the Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes Child and Parent Versions (ChIPS/P-ChIPS) (Weller, Weller, Rooney, & Fristad, 1999a, 1999b), structured interviews designed to assess DSM-IV-TR disorders (e.g., anxiety, ADHD, disruptive behavior disorder, and posttraumatic stress) in youth aged 6–18 years. The evaluator considers all available interview data to assign psychiatric diagnoses. ChIPS/P-ChIPS have high test-retest reliability and moderate-high correlations with diagnoses. Training IRR for diagnoses from ChIPS/P-ChIPS was excellent (κ=0.86). All diagnoses were finalized during a consensus conference with a licensed clinician. Ongoing assessment of depression using the KDRS and CDRS-R was completed at each of the seven study assessments of the RCTs (2 assessments prior to randomization, 4 occurring during the course of treatment, and 1 occurring at the end of treatment).

Side-Effects Review

Parents rated potential side-effects (constipation, diarrhea, stomachache, increased/decreased appetite, burping, fishy breath, and nausea) from 0 (absent) to 6 (severe) at each assessment.

Statistical Analyses

Missing data were estimated using multiple imputation procedures within SPSS 22. Five datasets were created using sequential regression imputation with child age, sex, and randomization group as predictors; results of pooled analyses are reported. Independent, repeated measures analyses of variance (R-ANOVAs) estimated effects of timepoint, randomization group, and their interaction to determine differential impact of study treatments on BRIEF GEC, BRI, and MI subscales. Three groupings were analyzed comparatively: 1) each of the three active interventions vs. placebo alone; 2) Ω3 (Combined and Ω3 monotherapy) vs. PBO (PEP monotherapy and PBO); 3) PEP (Combined and PEP monotherapy) vs. no PEP (Ω3 monotherapy and PBO). Cohen’s d values with Hedges’ correction were calculated for each analysis (Lakens, 2013).

Post-hoc regression analyses examined moderating effects of ADHD comorbidity and changes in depressive symptoms and predictive effects of study sample (bipolar vs. depressive), Ω3 adherence, therapy attendance, and caregiver depression history on BRIEF scores, while adjusting for treatment. The Bonferroni-Sidak correction was applied to control for type 1 error; thus, α=0.002 was used for these analyses.

Results

Participant Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

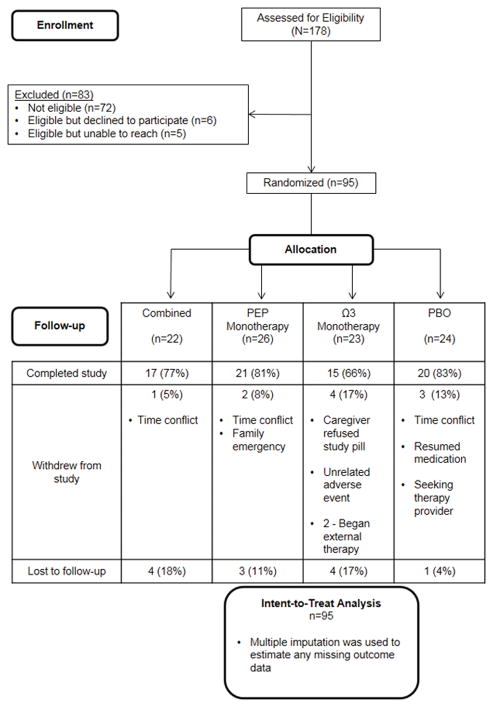

Figure 1 displays participant flow. Attrition did not differ significantly between treatment groups. Analyses using imputed data did not differ substantively from those using the original dataset with missing data (23%) with respect to parameter estimates or hypothesis tests.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram illustrating participant recruitment, randomization allocation, and completion/attrition. BRIEF was collected at screening (pre-intervention) and after 12 weeks of intervention.

Participants were approximately 11 years old on average, predominantly White, and male; one-third were enrolled in Medicaid (see Table 1). Participating parents were primarily middle-aged mothers. Common comorbid conditions were anxiety (n=73), ADHD (n=58), and disruptive behavior disorders (n=37). There were significantly more boys in the PBO-alone condition than in PEP monotherapy; no other demographic or clinical group differences were significant.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics and Clinical Characteristics. Different letter subscripts signify statistically differences between groups.

| Total (N = 95) | Combined (n = 22) | PEP (n = 26) | Ω3 (n = 23) | PBO (n = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| M ± SD or n (%) | |||||

| Age | 11.2 ± 2.2 | 11.0 ± 2.1 | 11.2 ± 2.3 | 11.7 ± 2.0 | 11.0 ± 2.5 |

| Sex: Male | 54 (56.8) | 14 (63.6)ab | 10 (38.5)b | 11 (47.8)ab | 19 (79.2)a |

| Race | |||||

| White | 58 (61.1) | 14 (63.6) | 18 (69.2) | 9 (39.1) | 17 (70.8) |

| Black/African-American | 25 (26.3) | 6 (27.3) | 5 (19.2) | 9 (39.1) | 5 (20.8) |

| Asian | 1 (1.1) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Biracial/Multiracial | 11 (11.6) | 1 (4.5) | 3 (11.5) | 5 (21.7) | 2 (8.3) |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 7 (7.4) | 4 (18.2) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.2) |

| IQ | 103 ± 16 | 105 ± 15 | 106 ± 16 | 98 ± 15 | 104 ± 15 |

| Diagnoses | |||||

| Depressive Disorder* | 72 (75.8) | 17 (77.3) | 19 (73.1) | 18 (78.3) | 18 (75.0) |

| Bipolar Disorder NOS/Cyclothymic Disorder | 23 (24.2) | 5 (22.7) | 7 (26.9) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (25.0) |

| Comorbid Anxiety | 73 (76.8) | 17 (77.3) | 21 (80.8) | 16 (69.6) | 19 (79.2) |

| Comorbid ADHD | 58 (61.1) | 12 (54.5) | 17 (65.4) | 11 (47.8) | 18 (75.0) |

| Comorbid DBD | 37 (38.9) | 9 (40.9) | 10 (38.5) | 8 (34.8) | 10 (41.7) |

| Medicaid Status | 32 (33.7) | 3 (13.6) | 8 (30.8) | 11 (47.8) | 10 (41.7) |

|

| |||||

| Parent Relationship | |||||

| Mother | 86 (90.5) | 21 (95.5) | 25 (96.2) | 20 (87.0) | 20 (83.3) |

| Father | 5 (5.3) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (4.2) |

| Grandmother | 4 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| Parent Age | 41.2 ± 8.0 | 43.0 ± 8.4 | 40.8 ± 6.7 | 39.7 ± 6.7 | 41.4 ± 9.8 |

| Parent Race | |||||

| White | 62 (65.3) | 16 (72.7) | 19 (73.1) | 9 (39.2) | 18 (75.0) |

| Black/African American | 27 (28.3) | 6 (27.3) | 4 (15.4) | 11 (47.8) | 6 (25.0) |

| Asian | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Biracial/Multiracial | 4 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Parent Ethnicity: Hispanic | 4 (4.2) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.2) |

| Not reported | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) |

PEP = Psychoeducational Psychotherapy + placebo; Ω3 = Omega-3 Monotherapy; PBO = Placebo alone; ADHD = Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; DBD = Disruptive Behavior Disorder.

Depressive disorder included major depression, dysthymia, or depressive disorder not otherwise specified as diagnosed at screening assessment.

Intervention Fidelity, Adherence, and Side Effects

Mean Ω3/PBO capsule adherence was 88.0±13.2%. Neither adherence to Ω3 nor reported side-effects significantly differed between Ω3 and PBO. On average, PEP families attended 14±6 sessions of a possible 24.

Intervention Effects on BRIEF Scores

R-ANOVA of GEC on the four randomized conditions demonstrated significant effects of timepoint [F(1,91)=13.41, p<0.001], treatment condition [F(3,91)=4.73, p=0.004], and their interaction [F(3,91)=4.83, p=0.004]. Ω3 alone and combined intervention were superior to PBO alone. Similar significant main and interactive effects (p-values<0.020) were found comparing the two Ω3 conditions versus the two PBO conditions but not when comparing the two PEP conditions to the two not receiving PEP (Table 2).. Pre-study GEC in PBO differed from both combined [t(42)=2.63, p=0.012] and PEP [t(46)=2.91, p=0.006] groups. Both combined and Ω3 monotherapy demonstrated significant improvements over time on GEC relative to placebo, with moderate effect sizes.

Table 2.

Pre- and Post-Intervention Means of BRIEF Composite and Subscale T-scores, Effect Sizes. d is Cohen’s effect size for independent samples with Hedges’ correction.

| BRIEF Scale | Intervention Group | Pre T-scores | Post T-scores | d (Placebo-controlled) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| M (SD) | |||||

| GEC | Combined | 67.60 (8.84) | 60.35 (11.81) | −0.67 | −1.26, −0.08 |

| PEP | 67.16 (10.55) | 68.04 (11.88) | 0.28 | −0.28, 0.83 | |

| Ω3 | 69.88 (8.91) | 64.86 (11.83) | −0.49 | −1.07, 0.09 | |

| PBO | 74.75 (8.15) | 73.55 (9.36) | --- | --- | |

| Received Ω3 (Combined & Ω3) | 68.77 (8.85) | 62.66 (11.93) | −0.70 | −1.12, −0.29 | |

| Received PBO (PEP & PBO) | 70.81 (10.13) | 70.68 (11.01) | --- | --- | |

| Received PEP (Combined & PEP) | 67.36 (9.71) | 64.51 (12.35) | 0.02 | −0.38, 0.43 | |

| No PEP (Ω3/PBO) | 72.37 (8.79) | 69.30 (11.42) | --- | --- | |

|

| |||||

| BRI | Combined | 67.93 (11.01) | 59.60 (14.88) | −0.70 | −1.30, −0.11 |

| PEP | 68.48 (10.81) | 67.09 (13.94) | 0.04 | −0.51, 0.60 | |

| Ω3 | 70.89 (11.19) | 65.50 (13.06) | −0.45 | −1.03, 0.13 | |

| PBO | 74.37 (9.70) | 72.62 (10.03) | --- | --- | |

| Received Ω3 (Combined & Ω3) | 69.44 (11.08) | 66.24 (8.43) | −0.59 | −1.00, −0.18 | |

| Received PBO (PEP & PBO) | 71.31 (10.62) | 69.75 (12.43) | --- | --- | |

| Received PEP (Combined & PEP) | 68.22 (10.79) | 63.66 (14.72) | −0.11 | −0.51, 0.29 | |

| No PEP (Ω3/PBO) | 72.67 (10.49) | 69.13 (12.06) | --- | --- | |

|

| |||||

| MI | Combined | 65.21 (9.26) | 61.50 (9.83) | −0.35 | −0.93, 0.24 |

| PEP | 64.79 (10.15) | 66.36 (10.98) | 0.41 | −0.15, 0.97 | |

| Ω3 | 67.23 (7.62) | 64.54 (12.87) | −0.17 | −0.74, 0.40 | |

| PBO | 72.26 (7.90) | 71.12 (9.17) | --- | --- | |

| Received Ω3 (Combined & Ω3) | 66.24 (8.43) | 63.05 (11.51) | −0.41 | −0.81, 0.00 | |

| Received PBO (PEP & PBO) | 68.38 (9.80) | 68.65 (10.34) | --- | --- | |

| Received PEP (Combined & PEP) | 64.98 (9.65) | 64.13 (10.67) | 0.12 | −0.28, 0.52 | |

| No PEP (Ω3/PBO) | 69.80 (8.09) | 67.90 (11.52) | --- | --- | |

--- indicates the reference group for the effect sizes of the preceding groups. d is calculated from the difference in mean change score of treatment from that of reference divided by pooled SD of the change scores. Negative d-value can be interpreted as treatment group outperforming reference. GEC = Global Executive Composite; BRI = Behavior Regulation Index; MI = Metacognition Index; PEP = Psychoeducational Psychotherapy Monotherapy; Ω3 = Omega-3 Monotherapy; PBO = Placebo. T-scores between 65 – 69 indicate borderline clinical elevation. T-scores ≥ 70 indicate significant clinical elevation.

BRI analyses demonstrated significant effects of timepoint [F(1,91)=21.62, p<0.001], treatment condition [F(3,91)=3.05, p=0.033], and their interaction [F(3,91)=3.40, p=0.042]. Similar to GEC analysis, pre-study differences existed between combined and PBO [t(42)=2.04, p=0.047] and PEP and PBO [t(46)=2.51, p=0.016]. Effects were significant for time (p<0.001) and time-by-treatment interaction (p=0.004) for aggregated Ω3 conditions vs. aggregated placebo. Aggregating PEP conditions yielded only a significant time effect (p<0.001). Both Ω3 conditions demonstrated significant improvements in BRI with moderate effect sizes (Table 2).

MI analyses demonstrated significant effect of treatment condition [F(3,91)=3.81, p=0.013] with non-significant effects of time [F(3,91)=3.10, p=0.082] and time-by-treatment interaction [F(3,91)=3.10, p=0.093]. Overall differences existed for combined versus PBO [t(42)=3.16, p=0.003] and PEP versus PBO [t(46)=2.42, p=0.020]. Notably, combining both Ω3 conditions versus both PBO conditions yielded significant treatment (p=0.04) and treatment-by-time interaction (p=0.04), but not so for aggregating PEP conditions. Both Ω3 conditions demonstrated moderate pre-post effect sizes on MI (Table 2).

Post-hoc Analyses

Examination of combined therapy advantage over Ω3 monotherapy demonstrated small, non-significant effects on GEC (d=−0.23), BRI (d=−0.32), and MI (d=−0.10).

ADHD comorbidity was non-significantly associated with treatment effect. ADHD comorbidity was associated with higher EF impairment on each outcome (i.e., significant main effects) but did not contribute to change in BRIEF scores or significantly moderate the effect of Ω3 on change in GEC, BRI, or MI whether comparing all four randomization groups or pooled Ω3 versus pooled placebo.

CDRS-R and KDRS scores were entered as dependent variables into respective mixed effects linear models with time as a predictor. Slopes were extracted for each participant to yield indicators of depressive symptom change. In independent regressions, these slopes were modelled as predictors of endpoint BRIEF subscale scores while controlling for treatment and pre-intervention subscale score. Overall, CDRS-R and KDRS changes were not significantly associated with change in GEC, BRI, or MI scores. Change in depressive symptoms did not significantly mediate treatment effects whether comparing all four randomization groups or pooled Ω3 versus placebo groups.

Presence of ADHD diagnosis and CDRS-R and KDRS slopes were also entered simultaneously into models predicting endpoint GEC, BRI, and MI while controlling for baseline scores of each measure and covarying with treatment condition. There were no meaningful changes in significance from the analyses without these covariates.

Study sample (bipolar versus depressive), Ω3 adherence, number of therapy sessions attended, and caregiver depression history were not significantly associated with endpoint GEC, BRI, or MI while controlling for treatment and pre-intervention subscale score.

Discussion

EF impairments are present in many disorders, including mood disorders. In this study, all treatment conditions, compared to placebo, were associated with clinically elevated pre-intervention EF impairment. Groups receiving Ω3 supplementation were associated with significant improvement in EF over time. Both groups receiving Ω3 demonstrated medium or better placebo-controlled effect sizes. EF related to inhibition control, adaptability to emotions, and cognitive flexibility (i.e., BRI) was more robustly associated with intervention than EF related to task initiation, planning, and organization (i.e., MI). Interestingly, EF improvement was independent of changes in depressive severity or having ADHD.

These findings have implications beyond mood disorders and are compatible with the RDoC emphasis advocated by NIMH. EF impairment is a prominent characteristic of ADHD, and ADHD symptoms have been responsive to omega-3 supplementation with small effect (Bloch & Qawasmi, 2011; Chang et al., 2017). Most study participants had comorbid ADHD; however, ADHD comorbidity did not significantly influence treatment outcome despite conferring nominally greater benefit. The absence of significant moderation could be a function of sample size, but youth without ADHD also showed moderate benefit. Remarkably, effects for EF are considerably larger than those reported for ADHD symptoms. Possible explanations for greater effect (relative to most ADHD studies using Ω3) could be larger dosage used, higher EPA:DHA ratio, diagnostic difference, or that crosscutting EF impairment responds more to Ω3 than diagnostic symptoms of any one disorder (Bloch & Qawasmi, 2011).

Both EF impairments and mood symptoms may be related to immunological responses. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are associated with stress, both acute and chronic (Bierhaus et al., 2003; Wolf, Rohleder, Bierhaus, Nawroth, & Kirschbaum, 2009), and correlate positively with depressive severity. Pathways from cytokine-induced inflammation to depressive symptoms have been extensively investigated (Dantzer, O’Connor, Lawson, & Kelley, 2011). One proposed mechanism links cytokines to activation of an enzyme that degrades tryptophan, an amino acid. The degradation of tryptophan within microglial cells of the central nervous system produce kynurenine, which is further degraded into neurotoxic metabolites (Myint & Kim, 2003). These metabolites may increase risk for depression and associated EF impairment by decreasing prefrontal cortex (PFC) activity and by dampening functional connectivity between the PFC and emotion-associated brain regions. PFC hypometabolism has been measured in patients administered interferon-alpha, a cytokine used in treatment of hepatitis C and associated with increased depressive severity (Juengling et al., 2000). Although most work was conducted with adults, one study noted that melancholic features of adolescent depression were associated with elevated kynurenine levels and low tryptophan (Gabbay et al., 2010). Cytokine-induced depressive symptoms and EF impairments may be key intervention targets for youth mood disorder. Ω3 inhibits cytokine production and has anti-inflammatory properties (Babcock, Helton, & Espat, 2000) that may partially reverse inflammation-induced mood and EF impairment.

Study limitations should be noted. First, the BRIEF, possibly reflecting parental bias, may differ from observation and performance-based tests. It is a measure of observable behavior reflective of EF skills. However, the BRIEF has been cited as being a broader measure of global EF, being less sensitive to children’s language and other fundamental systems subserving higher cognition, and (by measuring EF in everyday function) having greater ecological validity than clinic-based assessments (Vriezen & Pigott, 2002). If parental bias were influencing the ratings, we would expect more effect from the parent-unmasked PEP than from the fully-masked Ω3. Second, results may not generalize to an EPA:DHA ratio other than the 7:1 used in this study. The optimal EPA:DHA ratio for mood disorders or EF deficits is unknown. Future studies should compare different ratios. Third, previous trials of psychosocial interventions for mood disorders in youth have demonstrated decreased symptom severity at longer-term follow-up (Fristad, Verducci, Walters, & Young, 2009). Such follow-up would yield information on lasting effects of Ω3 and could demonstrate a delayed benefit from PEP. Fourth, it is unclear whether Ω3-related EF improvement might generalize to youth without mood disorders. Fifth, the placebo had statistically higher pre-study EF impairments. This failure of randomization may have inflated or deflated treatment effects; however, PEP monotherapy showed a similar trend to placebo without such a pre-study difference, giving credibility to Ω3 contributing to the effect. Sixth, children with marked-severe mood symptoms or bipolar I/II disorder were excluded, limiting generalizability of results. Seventh, data are not available on the adequacy of participant masking (i.e., their ability to guess whether they were on Ω3 or placebo). A separate analysis of these trials showed that Ω3 supplementation was guessed correctly no greater than chance (50% of the time) by study assessors, indicating study staff were adequately masked (Jones, Black, Arnold, & Fristad, 2017). As this study reflects secondary analyses, replication in studies designed to examine Ω3 effects on EF is needed.

Conclusions

This analysis is the first to examine associations of Ω3 and family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy with EF impairments among youth with mood disorders. Previous research has demonstrated EF impairment to be independent of mood severity, indicating that EF is a separate dimension of mood dysregulation that is likely impacted by mood but not driven by it (Shear, DelBello, Lee Rosenberg, & Strakowski, 2002). In the current sample, parents of children receiving Ω3 frequently commented that their children showed improvement in distractibility and ability to plan for and problem-solve stressful situations. Many also demonstrated concurrent improvement in dysphoric mood, irritability, and self-esteem. Future work should aim to optimize Ω3 ratios contributing to improved EF, understand the moderating effect of EF on treatment for mood symptoms, further examine associations of EF and mood severity, and include temporal associations of EF and mood symptoms and their response to interventions.

Supplementary Material

CONSORT checklist.

Key Points.

Omega-3 supplementation may improve executive functioning in mood-disordered youth with or without ADHD. Meta-analyses show improvement in inattention/hyperactivity symptoms, which are related to executive functioning, in youth with ADHD without mood disorder.

Omega-3 has a lower rate of side effects than prescription medicines used to treat attention and mood disorders.

Participants receiving omega-3 compared to those on placebo showed improvement in executive functioning after a 12-week trial (medium-high, placebo-controlled effect size, d=0.70).

Participants receiving omega-3 in conjunction with psychoeducational psychotherapy did the best in this 12-week trial.

Omega-3 supplementation should be considered clinically as an adjunct treatment in youth with mood disorders, particularly those showing heightened problems with executive functioning.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIMH (R34MH090148 and R34MH085875) and Award Number UL1RR025755 from the National Center for Research Resources. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of NIMH. The authors would like to thank the staff who collected data and provided therapy, the families who participated, and OmegaBrite, who provided study capsules. The following disclosures apply: MF receives royalties from American Psychiatric Press, Child & Family Psychological Services and Guilford Press, honoraria from Physicians Post-Graduate Press and research funding from Janssen. L.EA has received research funding from Curemark, Forest, Lilly, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Shire, Supernus, and YoungLiving (as well as NIH and Autism Speaks) and has consulted with or been on advisory boards for Gowlings, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Seaside Therapeutics, Sigma Tau, Shire, and Tris Pharma and received travel support from Noven. AY has received research funding from Psychnostics, LLC. The remaining author has reported no conflicting or potential conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: See Acknowledgements for disclosures.

References

- Babcock T, Helton WS, Espat NJ. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA): an antiinflammatory omega-3 fat with potential clinical applications. Nutrition. 2000;16(11–12):1116–1118. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierhaus A, Wolf J, Andrassy M, Rohleder N, Humpert PM, Petrov D, et al. A mechanism converting psychosocial stress into mononuclear cell activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(4):1920–1925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438019100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B. Longitudinal course of pediatric bipolar disorder. The American journal of psychiatry. 2007;164(4):537–539. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, et al. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):175–183. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch MH, Qawasmi A. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptomatology: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(10):991–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BL, Iverson GL, Sherman EM, Roberge MC. Identifying cognitive problems in children and adolescents with depression using computerized neuropsychological testing. Appl Neuropsychol. 2010;17(1):37–43. doi: 10.1080/09084280903526083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda AE, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Marttunen M, Suvisaari J, Lonnqvist J. A review on cognitive impairments in depressive and anxiety disorders with a focus on young adults. J Affect Disord. 2008;106(1–2):1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JC, Su KP, Mondelli V, Pariante CM. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Youths with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials and Biological Studies. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017 doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EH, Hanstock TL, Hirneth SJ, Kable CJ, Garg ML, Hazell PL. Reduced mania and depression in juvenile bipolar disorder associated with long-chain [omega]-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;63(8):1037–1040. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2008.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Lawson MA, Kelley KW. Inflammation-associated depression: from serotonin to kynurenine. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(3):426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre T, Hughes C, Emslie G, Stavinoha P, Kennard B, Carmody T. Executive functioning in childfren and adolescents with Major Depressive Disorder. Child Neuropsychology. 2009;15(1):85–98. doi: 10.1080/09297040802577311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, Fristad MA, Birmaher B, Kowatch RA, Arnold LE, et al. Characteristics of children with elevated symptoms of mania: the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1664–1672. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05859yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Goldberg-Arnold JS, Leffler JM. Psychotherapy for children with bipolar and depressive disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Verducci JS, Walters K, Young ME. Impact of multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy in treating children aged 8 to 12 years with mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(9):1013–1021. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Vesco AT, Young AS, Healy KZ, Nader ES, Gardner W, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of omega-3 and Individual-Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy for children and adolescents with depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1233500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Young AS, Vesco AT, Nader ES, Healy KZ, Gardner W, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Individual Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy & omega-3 fatty acids in youth with subsyndromal bipolar disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2015;25(10):764–774. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay V, Klein RG, Katz Y, Mendoza S, Guttman LE, Alonso CM, et al. The possible role of the kynurenine pathway in adolescent depression with melancholic features. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(8):935–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, et al. Reliability of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):450–455. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Child Neuropsychology. 2000;6(3):235–238. doi: 10.1076/chin.6.3.235.3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Helm J, Iucha C, Zahn-Waxler C, Hastings PD, Klimes-Dougan B. Are Executive Functioning Deficits Concurrently and Predictively Associated With Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015:1–15. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1041592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Black SR, Arnold LE, Fristad MA. Not all masks are created equal: Masking success in clinical trials of children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1342547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph MF, Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, Soares JC. A quantitative and qualitative review of neurocognitive performance in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008;18(6):595–605. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengling FD, Ebert D, Gut O, Engelbrecht MA, Rasenack J, Nitzsche EU, et al. Prefrontal cortical hypometabolism during low-dose interferon alpha treatment. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;152(4):383–389. doi: 10.1007/s002130000549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte ZA, Goodyer IM, Sahakian BJ. Selected executive skills in adolescents with recent first episode major depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(9):995–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol. 2000;41(1):49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint AM, Kim YK. Cytokine-serotonin interaction through IDO: a neurodegeneration hypothesis of depression. Medical Hypotheses. 2003;61(5–6):519–525. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(03)00207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Frankle WG, Mason NS, Muldoon MF, Moghaddam B. Improved working memory but no effect on striatal vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 after omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemets H, Nemets B, Apter A, Bracha Z, Belmaker RH. Omega-3 treatment of childhood depression: A controlled, double-blind pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1098–1100. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington B, Bennetto L, McAleer O, Roberts R. Executive functions and working memory: Theoretical and measurement issues. In: Lyon G, Krasnegor N, editors. Attention, memory, and executive function. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company; 1996. pp. 327–348. [Google Scholar]

- Roman GD, Ensor R, Hughes C. Does executive function mediate the path from mothers’ depressive symptoms to young children’s problem behaviors? J Exp Child Psychol. 2016;142:158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear PK, DelBello MP, Lee Rosenberg H, Strakowski SM. Parental reports of executive dysfunction in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Child Neuropsychol. 2002;8(4):285–295. doi: 10.1076/chin.8.4.285.13511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgis V, Silk TJ, Vance A. Executive function and attention in children and adolescents with depressive disorders: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(4):365–384. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0675-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriezen ER, Pigott SE. The relationship between parental report on the BRIEF and performance-based measures of executive function in children with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Child Neuropsychology. 2002;8(4):296–303. doi: 10.1076/chin.8.4.296.13505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Doering B, Helmreich I, Lieb K, Tadic A. A meta-analysis of executive dysfunctions in unipolar major depressive disorder without psychotic symptoms and their changes during antidepressant treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(4):281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Muller C, Helmreich I, Huss M, Tadic A. A meta-analysis of cognitive functions in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(1):5–19. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller EB, Weller RA, Rooney MT, Fristad MA. Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes- Parent Version (P-ChIPS) Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1999a. [Google Scholar]

- Weller EB, Weller RA, Rooney MT, Fristad MA. Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes (ChIPS) Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1999b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh MC, Pennington BF, Groisser DB. A normative-developmental study of executive function: A window on prefrontal function in children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 1991;7(2):131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf JM, Rohleder N, Bierhaus A, Nawroth PP, Kirschbaum C. Determinants of the NF-kappaB response to acute psychosocial stress in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(6):742–749. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

CONSORT checklist.