Abstract

Multiple regulatory mechanisms control osteoblast differentiation and function to ensure unperturbed skeletal formation and remodeling. In this study we identify histone lysine-specific demethylase 1(LSD1/KDM1A) as a key epigenetic regulator of osteoblast differentiation. Knockdown of LSD1 promoted osteoblast differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) in vitro and mice lacking LSD1 in mesenchymal cells displayed increased bone mass secondary to accelerated osteoblast differentiation. Mechanistic in vitro studies revealed that LSD1 epigenetically regulates the expression of WNT7B and BMP2. LSD1 deficiency resulted in increased BMP2 and WNT7B expression in osteoblasts and enhanced bone formation, while downregulation of WNT7B- and BMP2-related signaling using genetic mouse model or small-molecule inhibitors attenuated bone phenotype in vivo. Furthermore, the LSD1 inhibitor tranylcypromine (TCP) could increase bone mass in mice. These data identify LSD1 as a novel regulator of osteoblast activity and suggest LSD1 inhibition as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of osteoporosis.

Epigenetics: Taking the brakes off bone formation

A molecular brake controlling the differentiation of bone-forming osteoblasts has been identified, which could provide a new therapeutic target for osteoporosis. LSD1 regulates the expression of various genes by interfering with the ability of the cellular machinery to bind to DNA and transcribe it. A previous study had suggested that inhibiting LSD1 in stem cells from human fat promoted the formation of new osteoblasts. To further investigate its role in bone development, Weiguo Zou at the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology and colleagues engineered mice which lacked LSD1 in their mesenchymal cells–precursors of bone, muscle and fat cells—the animals had increased numbers of osteoblasts and greater bone mass. Further experiments revealed that blocking LSD1 resulted in increased expression of two osteoblast-stimulating factors, although it may also influence bone resorbing osteoclasts.

Introduction

Bone is a dynamic organ that supports locomotive activity, maintains blood calcium levels, serves as a reservoir for hematopoietic stem cells, and houses the brain and spinal cord. The maintenance of bone is accomplished by continuous remodeling throughout life via the balanced activity of mesenchymally derived osteoblasts and hematopoietically derived osteoclasts.1 Osteoblasts are the bone-forming cells, which synthesize collagens and proteins such as osteocalcin and osteopontin to form bone matrix while osteoclasts resorb bone in response to microfractures. The differentiation of osteoblasts from mesenchymal progenitors is regulated by multiple developmental signals, transcription factors (such as Runx2 and Osterix) and cytokines.2

LSD1 is a flavin-containing amino oxidase that specifically catalyzes the demethylation of monomethylated and dimethylated histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) residues and generally functions as a transcriptional repressor.3 LSD1 has also been shown to promote nuclear hormone receptor induced transcription via H3K9me1/me2 demethylation.4,5 Germline deletion of Lsd1 in mice results in embryonic lethality and embryonic stem cells lacking LSD1 show impaired differentiation potential indicating an important role for LSD1 during embryogenesis.6,7 LSD1 also orchestrates the emergence and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells, 8–10 regulates fat metabolism and modulates p53 signaling pathway.11,12 In addition, LSD1 has been associated with multiple human malignancies including prostate cancer, bladder cancer, leukemia, and others.13,14 Because of the important role of LSD1 in these diseases, pharmacological LSD1 inhibitors have been developed.15–17 A recent study showed that inhibition of LSD1 in human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs) using LSD1 inhibitors enhanced osteoblastogenesis,18 but the precise in vivo role of LSD1 in bone development and remodeling remains to be determined.

Here we explored the function of LSD1 in osteoblasts using a genetic mouse model and mechanistic in vitro studies. Mice with conditional deletion of Lsd1 in mesenchymal cells exhibited an enhanced bone mass phenotype with increased osteoblast numbers. LSD1 negatively regulated the expression of BMP2 and WNT7B via demethylation resulting in increased BMP2-induced BMP signaling and WNT7B induced mTOR signaling in LSD1-deficient osteoblasts. Moreover, inhibition of LSD1 using the small inhibitor tranylcypromine (TCP) increased bone mass in mice. Together, these findings provide strong in vivo evidence for the role of LSD1 as a repressor of osteoblastogenesis through repressing BMP2 and WNT7B expression and reveal it as a potential therapeutic target for osteoporosis.

Results

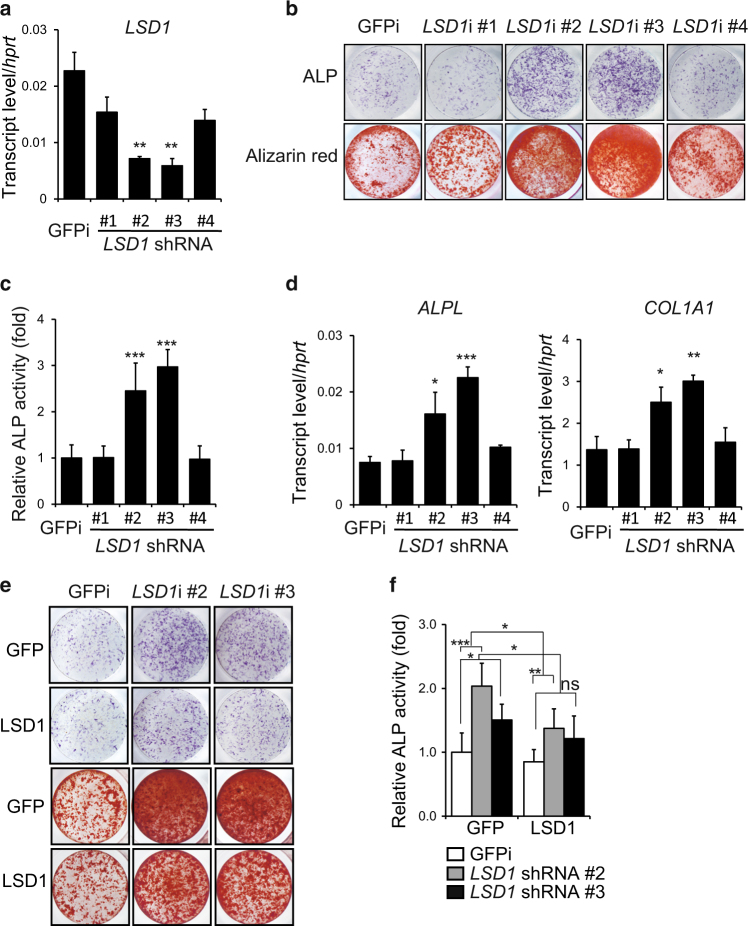

LSD1 inhibits osteoblast differentiation of hMSCs in vitro

We previously performed an RNAi-based loss-of-function screen in bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) to identify novel regulators of osteoblast differentiation19 and found that knockdown of LSD1 enhanced osteoblast differentiation. To verify this result, hMSCs transduced with four different shRNA lentivirus constructs targeting human LSD1 were cultured in osteoblast differentiation media. Knockdown of LSD1 enhanced osteoblast differentiation, as demonstrated by increased induction of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, an early marker of osteogenesis (Fig. 1a–c). Consistent with enhanced osteoblast differentiation, the expression of characteristic osteogenic marker genes including ALP and collagen1 alpha 1 (COL1A1) was increased in LSD1 knockdown cells (Fig. 1d). Alizarin red staining confirmed increased mineralization in LSD1 knockdown cultures at a later time point (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, overexpression of mouse Lsd1, which is not targeted by the human LSD1-specific shRNAs, abrogated the effects of LSD1 knockdown on ALP activity and mineralization capacity (Fig. 1e, f), thereby proving the specificity of the knockdown results and confirming that knockdown of LSD1 promotes osteoblast differentiation of hMSCs in vitro. Taken together, these data suggest that LSD1 plays a negative role in osteoblast differentiation.

Fig. 1.

LSD1 inhibits osteoblastogenesis of hMSCs in vitro. a RT-PCR analysis of the knockdown efficiency of LSD1 at day7 during hMSCs differentiation, n = 3, unpaired t-test, **P < 0.01. b, c ALP staining (b, upper panel), alizarin red staining (b, lower panel), and ALP quantification (c) of hMSCs infected with GFP- or LSD1-specific shRNA lentivirus at day7 or day14. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6), unpaired t-test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. d RT-PCR analysis of ALPL and COLLA1 expression at day7 during hMSCs differentiation. n = 3, unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. e, f Osteoblast differentiation was analyzed by ALP staining (e, upper panel), alizarin red staining (e, lower panel), and ALP quantification (f) after infection of hMSCs with indicated shRNA and LSD1 expression lentiviruses and subsequent culture for 7 days or 14 days. Data in f are presented as mean ± s.d (n = 6). ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns not significant.

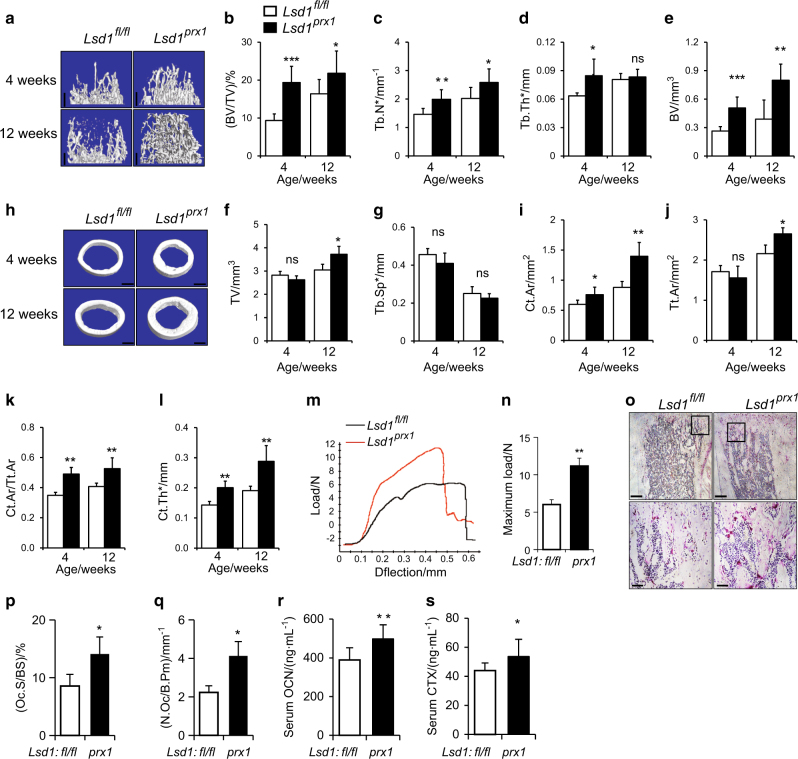

Deletion of Lsd1 in mesenchymal progenitor cells leads to increased bone mass in mice

To investigate the role of LSD1 in skeletal remodeling in vivo, we crossed mice with a floxed Lsd1 gene (hereafter called Lsd1fl/fl mice) with Prx1-cre mice that shows no basal phenotype20 to specifically delete the Lsd1 gene in mesenchymal progenitors (Prx1-Cre, Lsd1fl/fl;, hereafter Lsd1prx1). LSD1 protein was largely abrogated in long bone tissue of Lsd1prx1 mice (Figure S1 A). Lsd1prx1 mice displayed approximately 20% shorter stature and 30% lower body weight compared with Lsd1fl/fl littermate controls at 4 weeks of age, both genders showed the same phenotype (Figure S1 B-D). The fat store showed no significant difference between Lsd1prx1 mice and control mice (Figure S1 E-G). Lsd1prx1 mice also exhibited delayed chondrocyte/cartilage development and endochondral bone formation (Figure S1 H), indicating that LSD1 may play important roles in chondrocyte/cartilage development. We then used Microcomputed tomography (microCT) analysis to examine the bone development. Lsd1prx1 mice exhibited increased trabecular bone volume at 4 and 12 weeks of age (Fig. 2a–g). The trabecular number and trabecular thickness were increased in Lsd1prx1 mice (Fig. 2c, d). In addition to the trabecular phenotype, Lsd1prx1 mice also displayed increased cortical bone thickness (Fig. 2h–l). In contrast, Prx1-cre, Lsd1fl/+ mice did not show obvious bone phenotype (Figure S2 A-L). The parental bone of Lsd1prx1 mice also showed increased BV/TV and BMD, indicating that the intramembranous bone formation was also enhanced in Lsd1prx1 mice (Figure S2 M-O). We next analyzed the structural integrity of femurs from 4-week-old Lsd1prx1 and control mice by three-point bending tests. Consistent with the increase in bone mass, Lsd1prx1 femurs showed increased bone stiffness compared with Lsd1fl/fl littermate controls (Fig. 2m, n). H&E staining of sections from the proximal tibias from 4-week-old mice and histomorphometry analysis confirmed increased bone mass in Lsd1prx1 mice (Figure S2 P-T). In addition, we observed higher osteoclast activity in Lsd1prx1 mice by TRAP staining of sections from the tibia (Fig. 2o–q). The serum bone turnover markers, CTX and Osteocalcin, were also increased in Lsd1prx1 mice (Fig. 2r, s). Taken together, these data suggest that deletion of Lsd1 in mesenchymal cells increases bone turnover.

Fig. 2.

Deletion of Lsd1 in osteoblast progenitor cells leads to increased bone mass. a–l Lsd1prx1 mice exhibited increased bone volume. Femurs from 4 weeks and 12 weeks female Lsd1prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl mice were analyzed by μCT. 3D reconstructions of the trabecular bone (a) and midshaft cortical bone (h), quantitative parameters of trabecular bone (b–g) and cortical bone (i–l) were analyzed, bone volume (BV), total volume (TV), trabecular number per cubic millimeter (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), cortical thickness (C.Th), Tt.Ar (total cross-sectional area), and Ct.Ar (cortical bone area), n = 6, unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. m, n Three-point bend test was performed on femurs of 4-week-old Lsd1prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl littermates. Representative image of load-deflection diagram demonstrating the differences in the mechanical properties of bone from control and Lsd1prx1 mice (m) and the biomechanical properties maximum load was measured during the test (n), n = 5, unpaired t-test, **P < 0.01. o Histological analysis of TRAP-positive osteoclast populations in the tibia of 4-week-old Lsd1prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl mice. Data are representative of three independent experiments. p, q Histomorphometric analysis of bone resorption, osteoclast surface (Oc.S/BS), and osteoclast number (N.Oc/B.Pm) was shown. Statistical analysis, unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05. r, s The serum bone turnover marker CTX (bone resorption) and Osteocalcin (bone formation) were measured in 5-week-old Lsd1prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl mice. n = 10, unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Scale bar in a, h, o (upper panel): 0.5 mm, o (lower panel): 0.1 mm.

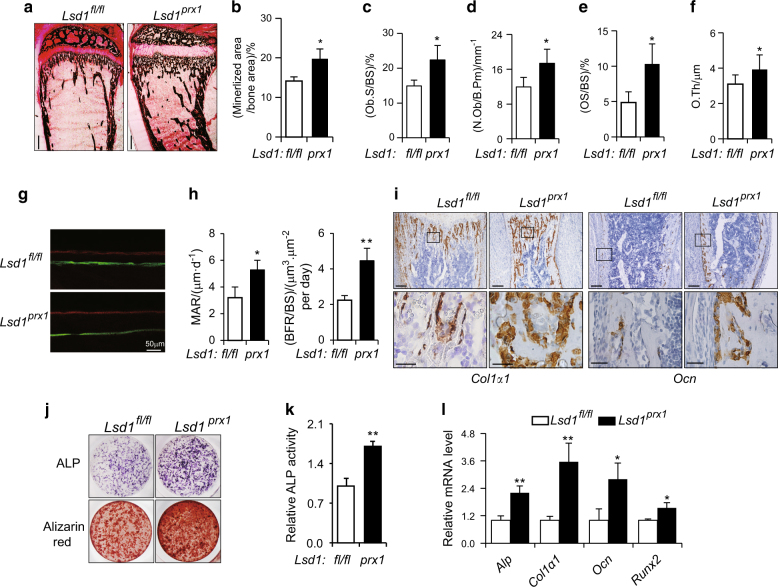

Increased osteoblast activity in Lsd1prx1 mice

To formally assess the bone mass phenotype in Lsd1prx1 mice, Von Kossa staining and histomorphometry were performed. Consistent with micro CT data, increased mineralized bone was observed in 4-week-old Lsd1 prx1 mice tibias (Fig. 3a, b). The bone formation parameters, including OS/BS, N.Ob/B.Pm, Ob.S/BS, and O.Th were increased in Lsd1 prx1 mice tibias (Fig. 3c–f). To gain further insight into whether the increased bone mass in Lsd1prx1 mice was due to increased bone formation, dynamic histomorphometry of tibias from 4-week-old Lsd1prx1 and control mice was performed. Fluorescent double labeling of the mineralizing front with calcein and alizarin red S showed an increase in mineral apposition rate (MAR) and bone formation rate (BFR) of Lsd1prx1 mice compared with control mice (Fig. 3g, h). Consistent with enhanced osteoblast activity, expression of the characteristic osteoblast genes osteocalcin (Ocn) and collagen I alpha 1 (Col1a1) was upregulated in the tibias of Lsd1prx1 mice compared with Lsd1fl/fl littermate controls (Fig. 3i). To explore whether knockout of Lsd1 promotes murine osteoblast differentiation, we performed ex vivo cultures of primary bone marrow stroma cells from Lsd1fl/fl and Lsd1prx1 mice. Osteoblast differentiation was enhanced in Lsd1 knockout cells as demonstrated by increased ALP activity and bone matrix formation (Fig. 3j, k), as well as upregulated expression of osteogenesis marker genes (Fig. 3l). These results indicate that the increased osteoblast differentiation and activity is responsible for the enhanced bone mass in Lsd1prx1 mice.

Fig. 3.

Increased osteoblast activity in Lsd1prx1 mice. a Von Kossa staining of proximal tibia from 4-week-old Lsd1prx1 and control mice, bar: 0.5 mm, n = 3. b Quantification of Von Kossa staining was represented as percentage of mineralized bone area determined by Image J program. c–f Bone histomorphometric analysis of proximal tibia from 4-week-old mice. The osteoid surface (OS/BS), osteoblast number (N.Ob/B.Pm), osteoblast surface (Ob./BS), and osteoid thickness (O.Th) are shown. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four mice, *P < 0.05. g Double labeling of mineralizing front with calcein and alizarin red S of tibia bone from Lsd1fl/fl and Lsd1prx1 mice was visualized by fluorescent microscopy, n = 3. h Analysis of mineral apposition rate (MAR) and bone formation rate (BFR) in Lsd1fl/fl and Lsd1prx1 mice. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3), Statistical analysis, unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. i In situ hybridization for collagen I (Col I) and osteocalcin(Ocn) in the tibia of 1-week-old Lsd1 prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl mice. Results are representative of two independent experiments. Scale bar, upper panel: 200 μm, lower panel: 50 μm. j ALP and alizarin red staining in osteogenic cultures of BMSCs. For ALP staining, cells were cultured for 7 days. For alizarin red staining, cells were cultured for 14 days. k Quantification of ALP activity, n = 5, unpaired t-test, **P < 0.01. l RT-PCR analysis of osteogenesis gene expression in Lsd1 prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl BMSC at cell culture day 7. Data are presented as mean ± s.d (n = 3), Statistical analysis, unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Wnt7b and Bmp2 expression is increased in Lsd1 deleted cells

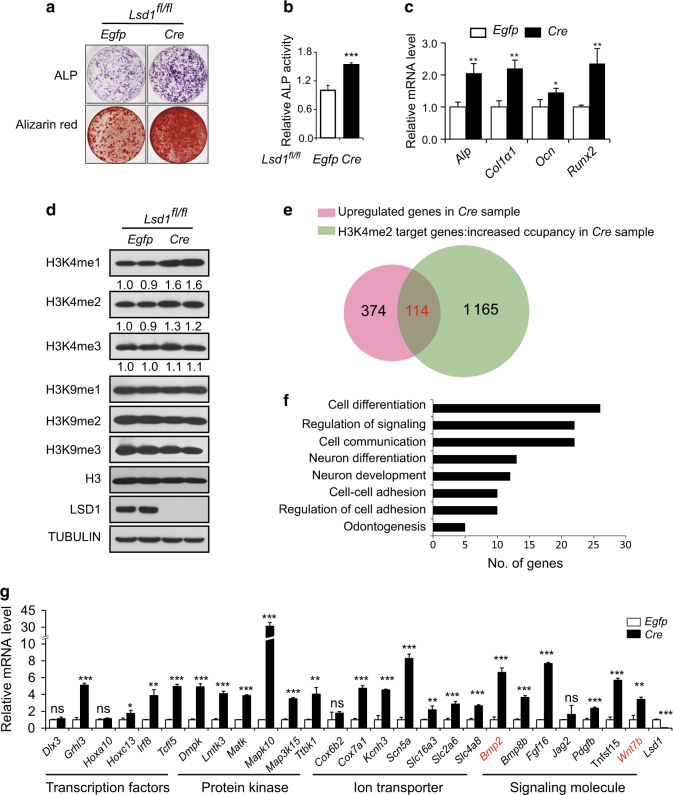

To identify genes regulated by LSD1 in osteoblasts, we infected calvarial osteoblast precursors from newborn Lsd1fl/fl mice with Cre-virus or control Egfp-virus followed by culture in osteoblast differentiation medium. As expected, ALP staining on day7 and alizarin red staining on day14 were increased in Cre-virus infected Lsd1fl/fl cells compared with Egfp-virus infected cells, consistent with enhanced osteoblast differentiation (Fig. 4a, b). The expression of osteoblast marker genes was also upregulated upon Lsd1 deletion (Fig. 4c). LSD1 protein was completely deleted in Cre-virus infected osteoblasts and total H3K4me1/2 levels were increased compared with Egfp-virus transduced cells while total H3K9me1/2 levels which are also targeted by LSD1 were unchanged (Fig. 4d). Next, we performed ChIP-seq using an antibody specific for H3K4me2 as well as RNA-seq on Lsd1fl/fl calvarial cells infected with Cre or Egfp virus. We found 1 165 genes with upregulated expression and 374 genes with increased enrichment of H3K4me2 marks in promoter regions in Lsd1 deleted samples compared with controls (Fig. 4e). As LSD1 is an H3K4me1/2 demethylase that generally acts as a transcriptional repressor, we focused on a smaller subset of 114 genes which showed both increased mRNA expression and increased enrichment of H3K4me2 marks (Fig. 4e and table S1). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis using the database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery (DAVID) bioinformatics tools revealed that many of these genes are involved in cell differentiation processes (Fig. 4f). Functionally, this group includes transcription factors, protein kinases, ion transporters, and signaling molecules (Fig. 4g). Differential expression of most of these genes was validated by RT-PCR (Fig. 4g). Among these genes, two secreted proteins, WNT7B and BMP2, have strong ability to induce osteoblast differentiation21,22 and knockdown of Lsd1 in embryonic stem cells has been shown to upregulate Bmp2.23

Fig. 4.

Wnt7b and Bmp2 expression is increased in Lsd1 deleted osteoblasts. a–c Lsd1fl/fl calvarial cells derived from P3 mice were infected with Cre-lentivirus or Egfp-lentivirus followed by culturing in osteoblast differentiation media for 14 days. ALP staining (day 7), alizarin red staining (day 14) (a) and quantification of ALP activity (b) of calvarial cells in osteogenic cultures. Data in b are the mean ± SD (n = 6), ***P < 0.001. Unpaired t-test was performed. c mRNA expression of osteoblast marker genes at day7 was analyzed by RT-PCR, n = 3, unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. d Histone H3 lysine4, lysine9 methylation, and LSD1 levels were measured by western blot. e Venn diagram shows the overlap of genes of increased expression level and increased H3K4me2 occupancy at the TSS region in LSD1 mutant osteoblasts. f Gene Ontology (GO) analysis within the 114 genes using the database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery (DAVID) bioinformatics tools. The enriched GO biological processes were identified and listed. The enrichment P-value is <0.01. g RT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of candidate genes in RNA-seq samples. Data in g represent the mean ± SD (n = 3) Unpaired t-test was performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Another Bmp gene, Bmp8b, is also upregulated in Lsd1 knockout osteoblast. To investigate whether Bmp8b can also stimulate osteoblastogenesis, we overexpressed Bmp8b in wild-type osteoblasts followed by culture under osteogenic conditions. The differentiation determined by ALP staining (day7) and alizarin red staining (day14) showed that overexpression of BMP8B, in contrast with BMP2, had no evident effects on osteoblastogenesis. (Figure S3 A&B). Overall, these data suggest that the increased expression of Wnt7b and Bmp2 may contribute to the enhanced osteoblast activity in Lsd1prx1 mice.

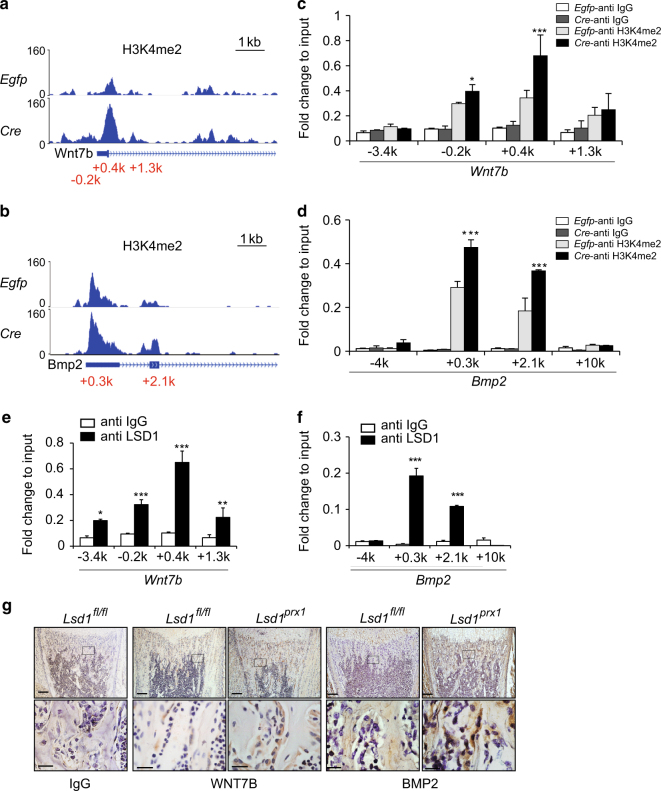

Wnt7b and Bmp2 are directly regulated by LSD1 in osteoblasts

Our ChIP-seq data indicated that H3K4me2 marks are specifically enriched in the promoter region of the Wnt7b and Bmp2 genes (Fig. 5a, b). ChIP-qPCR analysis confirmed H3K4me2 enrichment at the Wnt7b and Bmp2 promoters in Lsd1-deficient cells (Fig. 5c, d). To examine whether LSD1 could directly influence H3K4me2 levels at the Wnt7b and Bmp2 promoters, we performed ChIP-qPCR analysis using an LSD1-specific antibody and found that LSD1 directly bound to these regions (Fig. 5e, f). To investigate whether WNT7B and BMP2 protein levels were increased in vivo, we examined their expression in tibia bone which turned out that both proteins were upregulated in bone area of Lsd1prx1 mice compared with Lsd1fl/fl littermate controls (Fig. 5g). Additional evidence for a functional role of BMP2 downstream of Lsd1 deficiency stems from the forepaw phenotype of Lsd1Prx1 mice. The duplication of a regulatory element that leads to high expression level of BMP2 in the developing limb has been demonstrated to cause brachydactyly type A2 (BDA2), a malformation characterized by hypoplastic middle phalanges of the second and fifth fingers.24 Interestingly, we observed the same phenotype of hypoplastic middle phalanges of the second and fifth fingers in Lsd1prx1 mice, consistent with upregulated BMP2 expression in Lsd1-deficient mice (Figure S4 A&B). These data support the conclusion that LSD1 directly binds to the Wnt7b and Bmp2 promoters and regulates their expression.

Fig. 5.

Wnt7b and Bmp2 are directly regulated by LSD1 in osteoblasts. a, b Genomic tracks display ChIP-seq data using H3K4me2 across the promoter region of Wnt7b (a) and Bmp2 (b). c, d ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K4me2 enrichment in the Wnt7b (c) and Bmp2 (d) promoter regions in calvarial cells. n = 3 for each group, all data represent means ± SD ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. e, f ChIP-qPCR analysis of LSD1 enrichment in the Wnt7b (e) and Bmp2 (f) promoter regions in calvarial cells. n = 3 for each group, all data represent means ± SD Unpaired t-test was performed, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. g Immunohistochemistry for WNT7B and BMP2 showing increased expression in a coronal section of the proximal tibias of 1-week-old Lsd1 prx1 mice compared to littermate controls. The images are representative of three mice per group. Scale bar, upper panel: 200 μm, lower panel: 40 μm.

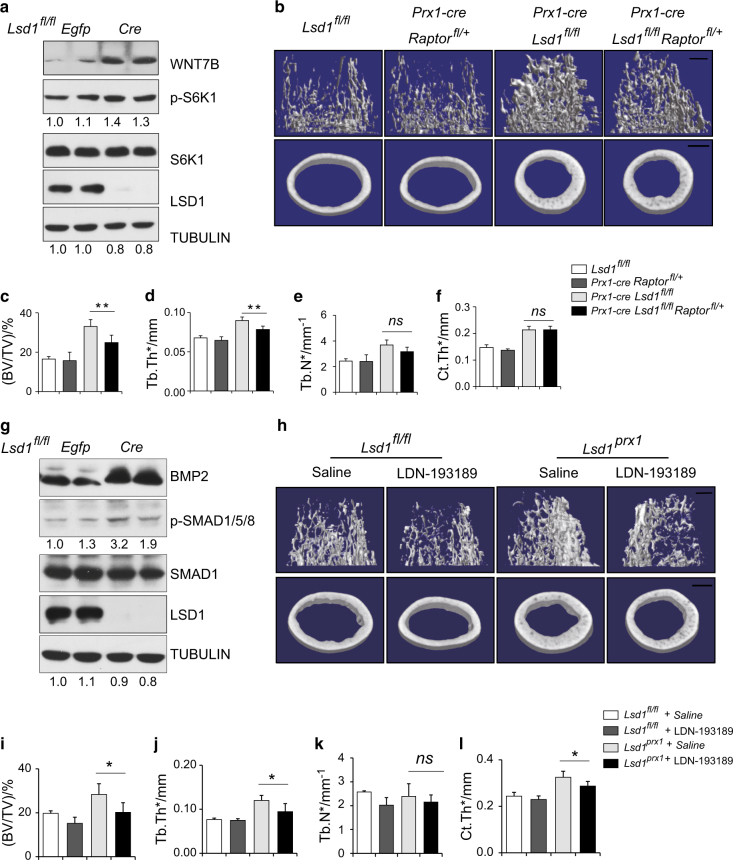

WNT7B-related mTOR signaling and BMP2-related BMP signaling contribute to the increased bone mass in in Lsd1prx1 mice

WNT7B has been reported to promote osteoblast differentiation in part through mTORC1 signaling rather than the canonical WNT signaling pathway21 and the mTOR inhibitor Rapamycin can inhibit osteoblast proliferation and differentiation.25 In agreement with this, we found WNT7B expression was increased in Lsd1-deficient osteoblasts along with increased phosphorylation of S6K1 protein (Fig. 6a) and treatment with Rapamycin for 14 days attenuated the enhanced osteoblast differentiation of Lsd1-deficient cultures, although not completely reversed (Figure S5 A&B). To investigate whether increased WNT7b-mTORC1 signaling in osteoblasts is responsible for the mice phenotype in vivo, we crossed the Raptorfl/fl mice with Prx1-cre, Lsd1fl/fl mice to block mTORC1 signaling in osteoblasts. Since Prx1-cre Raptorfl/fl mice exhibits neonatal death,26 we collected 6-week-old Prx1-cre, Raptorfl/+ Lsd1fl/fl and control mice for bone phenotype analysis. The Raptor mRNA level was decreased about 30% in long bone of Prx1-cre Raptorfl/+ mice (Figure S5 E). Prx1-cre, Raptorfl/+ trabecular bone mass are comparable to Lsd1 fl/fl mice, while Prx1-cre, Raptorfl/+ Lsd1fl/fl mice partially rescued the increased trabecular bone mass of Prx1-cre, Lsd1fl/fl mice although the cortical bone phenotype were not recued (Fig. 6b–f). These data suggested that Wnt7b-mTORC1 signaling partially contributed to the increased bone mass of Prx1-cre Lsd1fl/fl mice.

Fig. 6.

WNT7B related mTOR signaling and BMP2 related BMP signaling contribute to the increased bone mass in Lsd1prx1 mice. a Lsd1 fl/fl calvarial cells derived from P3 mice were infected with Egfp or Cre virus followed by culture in osteoblast differentiation medium for 7 days. WNT7B and pS6K1 levels were measured by western blot. Results are representative of two independent experiments. b–f Femurs from 6 weeks female mice (n = 4–6) were analyzed by μCT. b 3D reconstructions of the trabecular bone and midshaft cortical bone. Quantitative parameters of trabecular bone (c–e) and cortical bone (f) were analyzed. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed. **P < 0.01. Scale bar, 0.5 mm. g Lsd1 fl/fl calvarial cells derived from P3 mice were infected with Egfp or Cre virus followed by culture in osteoblast differentiation medium for 7 days. LSD1, p-SMAD1/5/8, and BMP2 levels were measured by western blot. Results are representative of two independent experiments. h–l Femurs from 9 weeks Lsd1prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl male mice (n = 4–6) after BMP inhibitor LDN-193185 injection for 4 weeks were analyzed by μCT. h 3D reconstructions of the trabecular bone and midshaft cortical bone. Quantitative parameters of trabecular bone (I–k) and cortical bone (l) were analyzed. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed. *P < 0.05. Scale bar in h: 0.5 mm.

Likewise, Lsd1 deletion in differentiating osteoblasts in vitro resulted in BMP2 upregulation (Fig. 6g). BMP2 promotes osteoblast differentiation through the canonical SMAD signaling pathway.27 Consistently, we observed increased phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8 protein in Lsd1 knockout osteoblasts (Fig. 6g). Next, we investigated whether inhibition of canonical SMAD signaling could reverse the enhanced osteoblast differentiation. Lsd1 deficient and control calvarial osteoblast cultures were treated with LDN-193189, a BMP receptor kinase inhibitor, for 14 days. The enhanced differentiation observed in Lsd1-deficient osteoblasts was significantly attenuated upon LDN-193189 treatment (Figure S5 C&D). To examine the in vivo effect of LDN-193189, Lsd1prx1 mice and littermate controls were treated with LDN-193189 for 4 weeks and femur bone mass were measured by micro CT. Both trabecular and cortical bone phenotype of Lsd1Prx1 mice were attenuated after LDN-193189 treatment (Fig. 6h–l). These data suggest that elevated BMP2 levels activating the canonical SMAD signaling pathway is involved in high bone mass formation of Lsd1Prx1 mice.

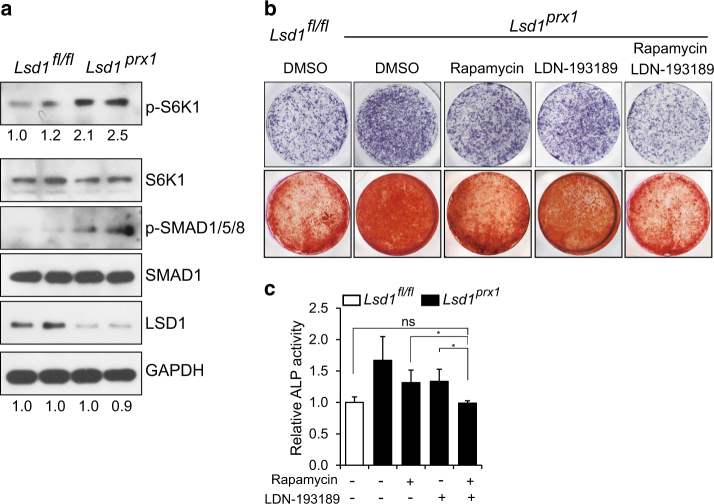

WNT7B and BMP2 promote osteoblast differentiation additively in Lsd1 deficient osteoblasts

We next examined whether there was evidence of increased WNT7B and BMP2 downstream signaling in primary Lsd1-deficient mice. As shown in Fig. 7a, both p-S6K1 and p-SMAD1/5/8 levels were increased in calvarial bone samples from 4-week-old Lsd1prx1 mice compared with Lsd1fl/fl littermate controls, consistent with increased WNT7B and BMP2 signaling activity. We then asked whether WNT7B and BMP2 act additively downstream of LSD1 deficiency to promote osteoblast differentiation. We generated lentiviral constructs to overexpress Wnt7b or/and Bmp2 in wild-type osteoblasts followed by culture under osteogenic conditions and analyzed cell differentiation state using ALP staining at day7 and alizarin red staining at day14. As expected, both Wnt7b and Bmp2 overexpression alone promoted osteoblast differentiation, which was further enhanced by co-expression of Wnt7b and Bmp2 (Figure S6 A&B). Next, we investigated whether blocking BMP2 and WNT7B signaling together abrogated the enhanced differentiation in Lsd1 null cells, the combination of Rapamycin and LDN-193289 but not the individual inhibitors completely reversed the enhanced differentiation of Lsd1prx1 osteoblasts back to wild-type levels (Fig. 7b, c). Taken together, our results indicate that LSD1 deficiency results in elevated WNT7B and BMP2 expression, which additively promote osteoblast differentiation and increased bone mass observed in Lsd1prx1 mice.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of BMP and mTOR signaling reverses enhanced osteoblast differentiation in Lsd1 deleted osteoblasts. a BMP and mTOR signaling protein levels were analyzed by western blot using primary calvarial bone samples from 4-week-old Lsd1prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl mice. Results are representative of two independent experiments. b, c ALP staining (day7) and alizarin red staining (day 14) (b) and ALP quantification (c) of osteoblast precursors from Lsd1fl/fl and Lsd1 prx1 mice treated with Rapamycin and LDN-193189 in osteogenic cultures for 14 days. Data in c are presented as mean ± s.d (n = 6). ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

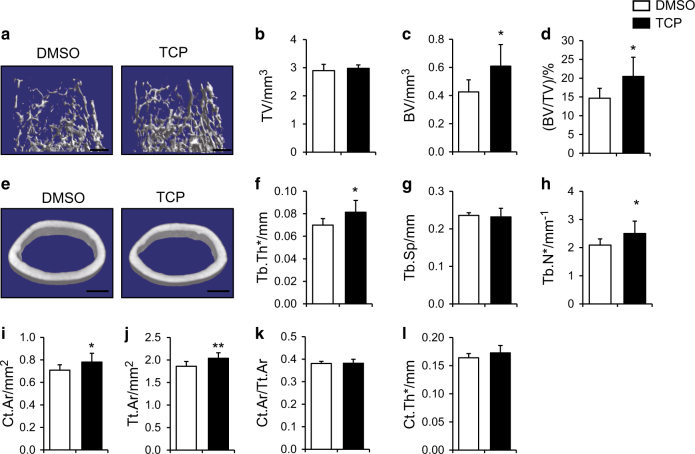

LSD1 inhibitor TCP increased mice bone mass

Tranylcypromine (TCP) is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor that has been widely used to inhibit the activity of LSD1 protein. To test whether TCP could upregulate Bmp2 and Wnt7b expression level, we treated calvairal osteoblast with 50 μM TCP for 48 h, the transcription level was measured by RT-PCR and we found that both Bmp2 and Wnt7b mRNA level was increased upon TCP treatment (Figure S7 A). We next sought to identify whether TCP increase mice bone mass in vivo, we injected 5-week-old wild-type mice with 3 mg·kg-1 TCP or DMSO subcutaneous every other day for 1 month. The trabecular bone volume and trabecular bone thickness as well as trabecular number were increased after TCP treatment (Fig. 8a–l). These data suggested that TCP had anabolic effects on bone formation and highlighted the potential clinical value for osteoporosis treatment of LSD1 inhibitors.

Fig. 8.

LSD1 inhibitor TCP increased mice bone mass. a–l Femurs from TCP-treated or DMSO-treated male mice were analyzed by μCT. 3D reconstructions of the trabecular bone (a) and midshaft cortical bone (e). Quantitative parameters of trabecular bone (b–h) and cortical bone (i–l) were analyzed, n = 7, statistical analysis, unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.05. Scale bar in a, e: 0.5 mm.

Discussion

Here we demonstrate that the histone H3K4 demethylase LSD1 has an important function in skeletal development in vivo to repress osteoblast activity and bone formation. We observed increased bone mass in mice lacking Lsd1 selectively in mesenchymal progenitor cells and showed that this was due to enhanced osteoblastogenesis. These results are consistent with a previous in vitro study, which demonstrated increased osteogenesis of human adipose-derived stem cells by LSD1 inhibition.18 Genome-wide expression analysis revealed markedly increased expression of osteoblast-stimulating factors Wnt7b and Bmp2 in LSD1 mutant osteoblasts and demonstrated that both of these factors stimulated osteoblastogenesis acting additively.

WNT ligands play a central role in bone development and homeostasis through β-catenin-dependent and -independent signaling pathways.28–30 In the β-catenin-dependent canonical WNT pathway, WNT binds to Frizzled receptors and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 or 6 (LRP5/6) that stabilizes cytosolic β-catenin and thereby stimulates transcription of downstream target genes. Wnt-β-catenin signaling is critical for osteoblast lineage commitment and promotes osteoblast precursor proliferation and differentiation.31–34 In the noncanonical WNT signaling pathway, WNT promotes bone formation through G-protein-linked PKCδ activation,30 and WNT7B activates mTORC1 to increase osteoblast differentiation.21 Targeted induction of Wnt7b in the osteoblast lineage resulted in profound bone mass accrual.21 Our study found that LSD1 acted as an upstream factor regulating Wnt7b expression in osteoblasts. Since WNT7B can induce other signaling pathways like mTORC2 and PKCδ,21,30 it is possible that these pathways may also be involved in the augmented osteoblast activity in Lsd1prx1 mice, a possibility which needs further investigation.

BMPs are a large family of morphogens, some of which, including BMP2, promote bone formation and increase osteoblastogenesis in vitro.35 Aberrant BMP signaling has been identified in several human skeletal diseases, for instance, mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1b (BMPR1B) or its ligand growth and differentiation factor 5 (GDF5) lead to autosomal-dominant brachydactyly type A2 (BDA2),36 and duplication of a regulatory enhancer that increases the expression of Bmp2 in the developing limb also causes BDA2.24 Our finding that mice lacking Lsd1 in limbs have a brachydactyly phenotype resembling BDA2 (Figure S4 A&B) thus provides supportive evidence that Lsd1 deficiency results in increased Bmp2 expression in vivo.

In this study, we found inhibition of LSD1 could regulate WNT7B and BMP2 to promote osteoblast differentiation. However, many other genes were also upregulated upon LSD1 deletion in osteoblast progenitors. Some of them are also associated with osteoblast differentiation, such as Pdgfb and Hoxa10,37,38 while most of them have unknown function in osteoblast. Further investigation about the functions of other LSD1-regulated genes will be needed to reveal the complex role of LSD1 in skeletal development.

The higher bone mass and greater bone strength in Lsd1prx1 mice was due to increased bone formation, as bone resorption in Lsd1prx1 mice is increased rather than impaired. This enhanced osteoclast activity may result from attempted coordination of osteoblast and osteoclast function in vivo to achieve balanced bone remodeling. Several LSD1 inhibitors such as GSK2879552, GSK-LSD1, TCP, Pargyline and some tranylcypromine analogs14–17,39 have been identified and used to effectively inhibit LSD1 activity. In line with our results that LSD1 conditional knockout mice displayed increased bone mass, recently, Lv et al. found that LSD1 inhibitor Pargyline can improve osteoblast differentiation and partially rescue the osteoporotic conditions in aged or ovariectomized mouse models.40 Consistent with this, we found that TCP can also increase mice bone mass. The effects of TCP are even stronger than Pargyline as TCP can improve the bone mass of young mice while Pargyline has little effects.40 Considering the wide range of LSD1 functions in many systems and cells, direct osteoblast-specific delivery system for LSD1 inhibitors is needed to ensure the safety and efficacy when it is used for the treatment of bone-related diseases. Currently, several osteoblast targeting delivery systems have been developed for drug delivery, such as aptamer-functionalized lipid nanoparticles and SDSSD-modified polyurethane nanomicelles.41,42 These may pave the way for LSD1 inhibitors to specifically target osteoblasts.

Overall, our study illustrates an unexpected function for the epigenetic regulator LSD1 in osteoblast differentiation, providing a potentially attractive targeted therapy for diseases of low bone mass.

Methods

Mice

Lsd1fl/fl mice43 bearing loxP sites flanking exons 6 of the Lsd1 gene were kindly provided by Dr. Michael Rosenfeld. Prx-1-Cre mice44 and Raptorfl/fl mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Lsd1fl/fl mice were cross-bred with Prx1-Cre mice to specifically delete Lsd1 expression in mesenchymal cells. All mice were bred and maintained under Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) conditions in the institutional animal facility of the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Age- and sex-matched littermates were used as control mice.

Cell culture

hMSCs were purchased from Cyagen. Primary cultures of murine osteoblasts were isolated from calvariae of 4- to 6-day-old Lsd1prx1 mice and Lsd1fl/fl littermates. Primary BMSCs were isolated from the long bone of mice, bone marrow was flushed with PBS and then pelleted at 1 200 r·min-1 for 4 min, the pellet was suspended in α-MEM with 10% FBS and cultured. Osteoblast differentiation was induced by culture in osteogenic media containing 50 μg·mL-1 ascorbic acid (Sigma, A5960) and 5 mmol·L-1 β-glycerophosphate (Sigma, G9422). For alizarin red staining, cells were fixed at day 14 of culture with 10% neutral formalin buffer and stained with alizarin red staining buffer (Cyagen) for 15 min, the mineralized area was determined using Image J program. For ALP assay, cells were fixed on day 7 with 10% neutral buffered formalin and subjected to ALP staining. For quantification of ALP activity, osteoblasts were incubated with Alamar Blue (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 h. After cellularity was measured at 580 nm, supernatants were removed and cells incubated with 6.5 mmol·L-1 Na2CO3, 18.5 mmol·L-1 NaHCO3, 2 mmol·L-1 MgCl2, and phosphatase substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min, ALP activity was then read with a luminometer at 405 nm. Rapamycin (Sigma) was used at a concentration of 10 nmol·L-1. LDN-193189 (Selleck) was used at a concentration of 10 nmol·L-1. Tranylcypromine hydrochloride (TCP) [TOCRIS (3852)] was used at a concentration of 50 μmol·L-1 in in vitro cell culture.

ChIP assays

Primary calvarial cells isolated from Lsd1fl/fl mice were infected with Egfp- or Cre-expressing lentivirus.45 Cells (1 × 106) were used for each immunoprecipitation as described previously.23 Briefly, cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. Glycine with a final of 125 mmol·L-1 was added to quench the crosslinking. Cells were scraped, washed by PBS three times and lysed with SDS buffer (1%SDS, 10 nmol·L-1 EDTA, 50 mmol·L-1 Tris). Samples were then sonicated to produce 0.2–0.7 kb DNA fragments. Eight micrograms indicated antibody were used for immunoprecipitation overnight at 4 °C. Protein G beads were then added and incubated for 2 h to isolate antibody-bound chromatin. The ChIP DNA was purified with PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and quantified by real-time PCR.

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-BMP2 antibody (ab14923), anti-LSD1 (ab17721), and anti-WNT7B (ab94915) were obtained from Abcam. Anti-Histone H3 (A2348), anti-H3K4me1 (A2355), anti-H3K4me2 (A2356), and anti-H3K4me3 (A2357) were purchased from ABclonal Technology. Anti-TUBULIN antibody (SC-23948) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-SMAD1 (6944), anti-phospho-SMAD1/5/9 (13820), anti-H3K9me1(14186), anti-H3K9me2(4658), anti-H3K9me3(14186), and anti-pS6K1(9234) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Vector construction

All shRNAs were cloned into pLKO.1 vector, the shRNA target sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S3.

Extracting bone protein

Four-week-old Lsd1prx1 mice and Lsd1fl/fl littermate controls were sacrificed, skin and muscle were removed and parietal bones or long bones (tibias and femurs) were harvested. Bones were placed in 2 mL cryovial and submerged in liquid nitrogen to freeze. Bones were then removed from cryovial, wrapped in aluminum foil, and pulverized with hammer. Bone fragments were transferred into cell lysis buffer and homogenized by homogenizer. Mixtures were centrifuged at 15 000 r·min-1 for 20 min at 4 °C, and supernatant was collected.

Histology and immunostaining

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h and incubated in 15% DEPC-EDTA (pH 7.8) for decalcification. Then specimens were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm. Immunohistochemistry was performed using TSA-biotin amplification system (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using antibody against BMP2 or WNT7B. The proportion of positive cells in each field was determined using Image J program. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes were generated according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, DIG-labeled antisense probes were generated to detect Col1a1, Ocn mRNA expression. Probes were then hybridized with paraffin sections and visualized using an anti-DIG HRP conjugate system.

MicroCT analysis

The mouse hindlimbs and skulls were skinned and fixed in 70% ethanol. Femurs were scanned using a Skyscan 1176 scanner (Bruker, Kartuizersweg, Belgium) with a spatial resolution of 8.96 μm. The X-ray energy is 70 kVp and 305 μA.

To analyze trabecular bone, a region of 2.0 mm of the distal metaphysis starting 0.7 mm from the proximal end of the distal femoral growth plate and a threshold of 75–255 permille were used. To analyze cortical bone, a region of 0.5 mm of the femoral cortical bone starting 3.7 mm from the proximal end of the distal femoral growth plate and a threshold of 125–255 permille were used. A Gaussian noise filter optimized for murine bone was applied to reduce noise in the thresholded 2D image. Three-dimensional reconstructions were created by stacking the two-dimensional images from the contoured regions. Indices of trabecular and cortical bone were shown according to the guidelines.46 Skulls were scanned using a Skyscan 1172 scanner (Bruker, Kartuizersweg, Belgium) with a spatial resolution of 9 μm. The X-ray energy is 49 kVp and 200 μA. Cylindrical regions of interest (ROIs) with a diameter of 3.5 mm in parietal bone and a threshold of 80–255 permille were used. A Gaussian noise filteroptimized for murine bone was applied to reduce noise in the thresholded 2D image.

Quantum GX microCT analysis

To analyze the fat store of Lsd1prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl mice, 4-week-old female mice were anesthetized and scanned by Quantum GX microCT (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) with a spatial resolution of 72 μm, view-imaging at 36 × 36 mm. The X-ray energy is 70 kVp and 114 μA. Subcutaneous and visceral fat volumes were analyzed.

RNA-seq

Total RNA was isolated using TRIZol (Sigma) from the egfp or cre virus-infected Lsd1fl/fl calvarial cells. cDNA library preparation and sequencing was performed according to the Illumina’s standard protocol.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was prepared using TRIzol (Sigma) and was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (TakaRa). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed with the BioRad CFX96 system. The sequences of oligonucleotides used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Three-point bending test

Four-week-old male mice femurs were collected and stored in 70% ethanol. Strength tests were performed with Instron 3345 at the right femur midshaft with a displacement rate of 0.03 mm·s-1 until the bone fractured; span length was 6 mm. Maximum load (a measurement of the maximum force that the bone withstood before fracture) was determined using load-deflection diagrams.

In vivo bone formation rate measurement

Four-week-old animals were injected intraperitoneally with calcein (20 mg·kg-1 body weight) and alizarin red S (50 mg·kg-1 body weight) on days −13 and −3 prior to tissue collection. Tibias were fixed in 70% (vol/vol) ethanol overnight, embedded in methyl methacrylate, and sectioned at 10 μm. Images were obtained using a fluorescence confocal microscope. Mineral apposition rate (MAR) in μm·d-1 and bone formation rate (BFR) were calculated from fluorochrome double labels at periosteal and endocortical surfaces.

Serum measurements

Blood samples were collected from 5-week-old Lsd1prx1 and control mice. Serum OTEOCALIN and CTX-1 were measured by using commercially available ELISA kits (Shanghai Suer Biological technology) according to the instructions of manufacturer.

In vivo TCP treatment

Five-week-old male C57BL6 mice were randomly divided into two groups. We injected these mice with either 3 mg·kg-1 TCP or DMSO subcutaneous every other day. One month after injection, we analyzed the bone mass of femurs of these mice with microCT.

In vivo LDN-193185 treatment

Five-week-old Lsd1prx1 mice and Lsd1fl/fl littermate controls were randomly divided into two groups separately. We injected these mice with either 3 mg·kg-1 LDN-193185 or saline i.p. every other day. Four weeks after injection, we analyzed the bone mass of femurs of these mice with microCT.

Statistics

All results are presented as the mean ± SD Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used when the data involve multiple group comparisons.

Study approval

All experiments were performed according to the protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, SIBS, CAS.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Michael Rosenfeld (University of California San Diego) for providing Lsd1fl/fl mice line and Minghan Tong (Chinese Academy of Sciences) for providing Ratorfl/fl mice line. We thank Dr. Laurie H. Glimcher, Dr. Marc Wein (Harvard Medical School), and Dr. Matthew Greenblatt (Weill Cornell Medical Center) for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank members of the Zou and Glimcher labs for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by grants from 973 Program from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) [2014CB964704, 2015CB964503] and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [31371463]. W.Z. is a scholar of the “1000 Young Talents Program of China” and “the National Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars” (NSFC) [81322027].

Author contributions

W.Z. designed the research; J.S., J.E., N.N., Y.Y., and G.Y. performed the research; Y.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.S., J.E., and W.Z. analyzed the data; and J.S. and W.Z. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41413-018-0015-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Zaidi M. Skeletal remodeling in health and disease. Nat. Med. 2007;13:791–801. doi: 10.1038/nm1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long F. Building strong bones: molecular regulation of the osteoblast lineage. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:27–38. doi: 10.1038/nrm3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Y, et al. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wissmann M, et al. Cooperative demethylation by JMJD2C and LSD1 promotes androgen receptor-dependent gene expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:347–353. doi: 10.1038/ncb1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perillo B, et al. DNA oxidation as triggered by H3K9me2 demethylation drives estrogen-induced gene expression. Science. 2008;319:202–206. doi: 10.1126/science.1147674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, et al. The lysine demethylase LSD1 (KDM1) is required for maintenance of global DNA methylation. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:125–129. doi: 10.1038/ng.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster CT, et al. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 regulates the embryonic transcriptome and CoREST stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30:4851–4863. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00521-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thambyrajah R, et al. GFI1 proteins orchestrate the emergence of haematopoietic stem cells through recruitment of LSD1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:21–32. doi: 10.1038/ncb3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi M, et al. LSD1/KDM1A promotes hematopoietic commitment of hemangioblasts through downregulation of Etv2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:13922–13927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517326112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saleque S, Kim J, Rooke HM, Orkin SH. Epigenetic regulation of hematopoietic differentiation by Gfi-1 and Gfi-1b is mediated by the cofactors CoREST and LSD1. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:562–572. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng X, et al. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 promotes brown adipose tissue thermogenesis via repressing glucocorticoid activation. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1822–1836. doi: 10.1101/gad.285312.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Periz G, et al. Regulation of protein quality control by UBE4B and LSD1 through p53-mediated transcription. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kauffman EC, et al. Role of androgen receptor and associated lysine-demethylase coregulators, LSD1 and JMJD2A, in localized and advanced human bladder cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2011;50:931–944. doi: 10.1002/mc.20758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris WJ, et al. The histone demethylase KDM1A sustains the oncogenic potential of MLL-AF9 leukemia stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:473–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohammad HP, et al. A DNA hypomethylation signature predicts antitumor activity of LSD1 inhibitors in SCLC. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schenk T, et al. Inhibition of the LSD1 (KDM1A) demethylase reactivates the all-trans-retinoic acid differentiation pathway in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Med. 2012;18:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nm.2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi L, Cui S, Engel JD, Tanabe O. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 is a therapeutic target for fetal hemoglobin induction. Nat. Med. 2013;19:291–294. doi: 10.1038/nm.3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge W, et al. The epigenetic promotion of osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells by the genetic and chemical blockade of histone demethylase LSD1. Biomaterials. 2014;35:6015–6025. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou W, et al. The microtubule-associated protein DCAMKL1 regulates osteoblast function via repression of Runx2. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:1793–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong J, et al. Matrix-embedded cells control osteoclast formation. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1235–1241. doi: 10.1038/nm.2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J, et al. WNT7B promotes bone formation in part through mTORC1. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noel D, et al. Short-term BMP-2 expression is sufficient for in vivo osteochondral differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22:74–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-1-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamo A, et al. LSD1 regulates the balance between self-renewal and differentiation in human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:652–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dathe K, et al. Duplications involving a conserved regulatory element downstream of BMP2 are associated with brachydactyly type A2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:483–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singha UK, et al. Rapamycin inhibits osteoblast proliferation and differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells and primary mouse bone marrow stromal cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008;103:434–446. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JQ, Long FX. mTORC1 signaling controls mammalian skeletal growth through stimulation of protein synthesis. Development. 2014;141:2848–2854. doi: 10.1242/dev.108811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshida Y, et al. Negative regulation of BMP/Smad signaling by Tob in osteoblasts. Cell. 2000;103:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med. 2013;19:179–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu X, et al. Osteocytes mediate the anabolic actions of canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in bone. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E478–E486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409857112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu X, et al. Noncanonical Wnt signaling through G protein-linked PKCdelta activation promotes bone formation. Dev. Cell. 2007;12:113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill TP, Spater D, Taketo MM, Birchmeier W, Hartmann C. Canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett CN, et al. Wnt10b increases postnatal bone formation by enhancing osteoblast differentiation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007;22:1924–1932. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miclea RL, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli-mediated control of beta-catenin is essential for both chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation of skeletal precursors. BMC Dev. Biol. 2009;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Z, Ren PG, Ma T, Smith RL, Goodman SB. Modulating osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells by modifying growth factor availability. Cytokine. 2010;51:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seemann P, et al. Activating and deactivating mutations in the receptor interaction site of GDF5 cause symphalangism or brachydactyly type A2. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2373–2381. doi: 10.1172/JCI25118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassan MQ, et al. HOXA10 controls osteoblastogenesis by directly activating bone regulatory and phenotypic genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:3337–3352. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01544-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen W, et al. PDGFB-based stem cell gene therapy increases bone strength in the mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E3893–E3900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501759112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hojfeldt JW, Agger K, Helin K. Histone lysine demethylases as targets for anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013;12:917–930. doi: 10.1038/nrd4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lv L, et al. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 inhibitor rescues the osteogenic ability of mesenchymal stem cells under osteoporotic conditions by modulating H3K4 methylation. Bone Res. 2016;4:16037. doi: 10.1038/boneres.2016.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang C, et al. Aptamer-functionalized lipid nanoparticles targeting osteoblasts as a novel RNA interference-based bone anabolic strategy. Nat. Med. 2015;21:288–294. doi: 10.1038/nm.3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, et al. Osteoblast-targeting-peptide modified nanoparticle for siRNA/microRNA delivery. ACS Nano. 2016;10:5759–5768. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, et al. Opposing LSD1 complexes function in developmental gene activation and repression programmes. Nature. 2007;446:882–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Logan M, et al. Expression of Cre recombinase in the developing mouse limb bud driven by a Prxl enhancer. Genesis. 2002;33:77–80. doi: 10.1002/gene.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang L, Jin Q, Lee JE, Su IH, Ge K. Histone H3K27 methyltransferase Ezh2 represses Wnt genes to facilitate adipogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7317–7322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000031107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bouxsein ML, et al. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010;25:1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.