Abstract

Stimulation of neuronal cells generally resorts to electric signals. Recent advances in laser-based stimulation methods could present an alternative with superior spatiotemporal resolution. The avoidance of electronic crosstalk makes these methods attractive for in vivo therapeutic application. In particular, nano-mediators, such as gold nanoparticles, can be used to transfer the energy from a laser pulse to the cell membrane and subsequently activate excitable cells. Although the underlying mechanisms of neuronal activation have been widely unraveled, the overall effect on the targeted cell is not understood. Little is known about the physiological and pathophysiological impact of a laser pulse targeted onto nanoabsorbers on the cell membrane. Here, we analyzed the reaction of the neuronal murine cell line Neuro-2A and murine primary cortical neurons to gold nanoparticle mediated laser stimulation. Our study reveals a severe, complex and cell-type independent stress response after laser irradiation, emphasizing the need for a thorough assessment of this approach’s efficacy and safety.

Introduction

Laser-based neuronal stimulation has opened up a new and promising field of research. Using a laser pulse instead of an electrical signal, the stimulus can be placed with unprecedented spatial resolution since electronic crosstalk is avoided. The light pulse can be converted to an adequate stimulus for a neuron by introducing light-sensing ion channels (optogenetics)1, photocleavable chemical compounds2,3 or by using exo- or endogenous photoabsorbers. In the case of photoabsorbers, it has been shown that the resulting rapid temperature transient increases the cell’s membrane capacitance, generating depolarizing currents that may trigger action potentials in nerve cells4,5. Water in and around the cell is the main absorber for direct infrared stimulation. However, bulk-heating of the irradiated area comprises the precision and selectivity of the stimulus. Nanoabsorbers like gold nanoparticles present a more specific alternative: When irradiated at their plasmon resonance, gold nanoparticles heat up rapidly and confer this heat to the plasma membrane5. The particles’ resonance frequency can be tuned by varying their geometrical characteristics, such as aspect ratio, or the shell-core composition. Spherical gold nanoparticles have an absorption maximum of approx. 530 nm, increasing with diameter6. Activation of neuronal cells has been demonstrated with both spherical5,7 and cylindrical8 gold nanostructures. Translating this stimulation mechanism to neural implants such as deep brain stimulators or cochlear implants could potentially reduce adverse effects that arise from imprecise electrical stimuli without the need for genetic modification, which is required in optogenetics. However, it is still widely unknown to what extent gold nanoparticle mediated laser stimulation interferes with the cellular metabolism and physiology. Depending on the parameters used for irradiation, rapid and substantial heating of gold nanoparticles may also cause protein denaturation, shockwaves and evaporation9. Next to reliable cell activation, biological safety is crucial for a neural implant. Therefore, a fundamental assessment of the method’s biological impact is essential before laser-based neurostimulation can be safely transferred to use in animal or human trials.

In order to investigate the impact of gold nanoparticle-meditated laser stimulation, we focused on calcium as a general marker of cellular stress signaling. Calcium is a universal messenger that is involved in numerous signaling pathways10,11. It plays a particularly important role in mediating stress responses and inducing apoptosis12–14. Tracking the calcium flux within a stimulated cell can provide information on various aspects of its reactions and health. The use of fluorescent calcium sensors allows monitoring of events like action potentials or stress responses in parallel to laser stimulation7,15,16. To gain information about the source of calcium flow, different possible pathways can be blocked one by one with specific inhibitors. In this study, we used fluorescent dyes to monitor intracellular calcium flux, lipid peroxidation events and membrane perforation in response to gold nanoparticle-mediated laser stimulation of the murine Neuro-2A (N2A) cell line and primary mouse cortical neurons. Various inhibitors were used to investigate the involvement of specific pathways. We integrated the information from different endpoints of a large data set to reconstruct the events immediately following a laser stimulus. Our results reveal an unspecific stress response that can be potentiated by calcium influx through membrane pores and intracellular feedback loops. Lipid peroxides and reactive oxygen species (ROS) might play a role as chemical mediators to forward the signal from the membrane into the cell, triggering a global and potentially lethal stress response.

Methods

Cell culture

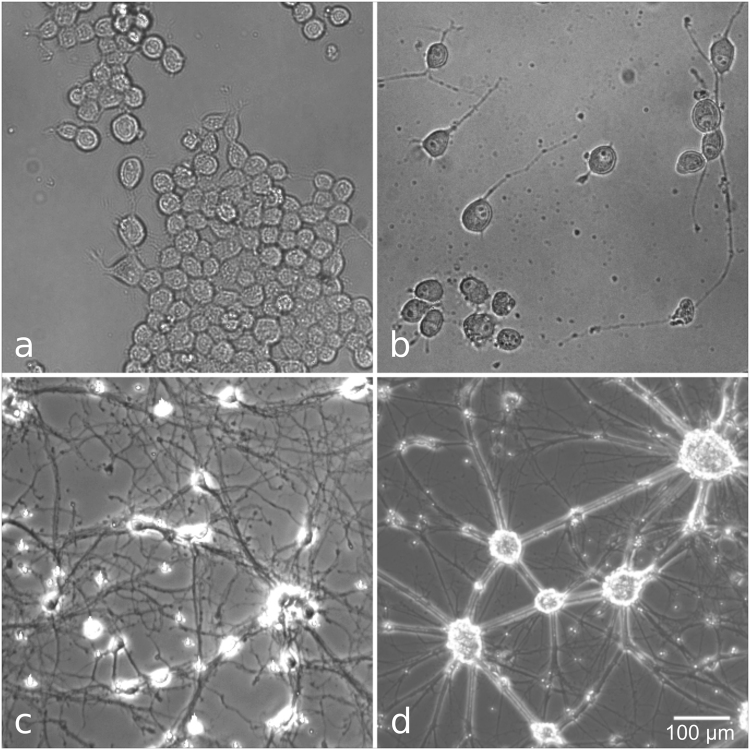

N2A cells were cultured in MEM Eagle with EBSS, supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin and 1% non-essential amino acids (all Pan Biotech, Germany), and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Prior to the experiments, 70,000 cells were seeded in a glass bottom dish (diameter 35 mm, ibidi, Germany). Cells were allowed to attach to the dish and subsequently cultured in serum-free medium for two to three days to promote neurite outgrowth and neuronal differentiation17 (Fig. 1a,b).

Figure 1.

Cell types used in this study. a, b: N2A cells before (a) and three days after serum deprivation (b). (c,d) Primary mouse cortical neurons, 7 (c) and 14 (d) days after start of culture. Mature cells formed dense clusters that did not allow for single cell stimulation. Therefore, neurons were used at the earlier time point. Scale bar corresponds to all panels.

Mouse cortical neurons (MCN) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA) and cultured according to the supplier’s protocol in 35 mm glass bottom dishes. Neurobasal® Medium supplemented with 0.5 mM GlutamaxTM-I and 2% B-27® was used as culture medium and refreshed every third day. After one week in culture, the neurons had developed multiple long neurites. Experiments were performed after 7–10 days in culture (Fig. 1c,d).

Laser manipulation setup

The setup used for single cell manipulation experiments has been described before15. A weakly focused pulsed Nd:YAG laser beam (λ = 532 nm, pulse width = 850 ps, repetition rate = 20.25 kHz; Horus, France) was guided onto the sample from above. The spot diameter was approx. 60 µm. An inverse epifluorescence microscope (Axio Observer, HBO 50 fluorescence excitation lamp, HAL100 brightfield lamp) was used to monitor fluorescence signals and obtain bright field images. Images were acquired with a cooled CCD-camera (ProgRes MF cool, Jenoptik, Germany). An OD6 notch filter (NF533-17, Thorlabs) protected the camera from laser irradiation. We used a 480 nm ± 15 nm bandpass filter for Fluo 4 excitation; emission was evaluated with a 520 nm longpass filter.

Laser stimulation and calcium response

On the day of experiment, cells were incubated for three hours with 200 nm gold nanoparticles (AuNP, Kisker Biotech) at a concentration of 0.5 µg/cm2. The same particles have been used before for laser transfection18,19, perforation studies and assessment of cellular stress15,20. Previous work has shown that after three hours of incubation time, particles have sedimented and are homogeneously distributed across the surface, where they attach to the cells’ membrane. The concentration used here results in 5–7 particles per cell18. Cellular uptake plays a negligible role for the size of particles and the time scale used in this study21. The medium was then replaced with serum free culture medium containing 1:1 Fluo 4-AM and Pluronic-F127 (5 or 1 µM for N2A cells and MCN, respectively; Sigma-Aldrich, USA). N2A cells and MCN were incubated with the dye for 60 or 30 minutes, respectively. The culture medium was then replaced with the respective experimental medium (either normal culture medium, a buffer, or medium containing an inhibitor; see below) containing propidium iodide (PI, 2 µg/mL, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The dish was placed in the manipulation setup and a 40 ms laser pulse was applied to the targeted cell. Only cells that were not part of a dense cluster (i.e. individual cells) were selected at random for stimulation. Additional cells located in the periphery of a laser spot were not evaluated. Radiant exposures varied from 17 to 51 mJ/cm2. Control experiments were conducted for each radiant exposure without the use of AuNP. The evoked calcium response was visualized via Fluo 4 imaging and recorded at five fps with an exposure time of 200 ms at linear gain settings. The sample size per dish was n ≈ 10 cells, and unless noted otherwise, three dishes were tested for each condition (four dishes for N2A cells in culture medium at 25 mJ/cm2). Observation time was 30 or 90 s in total, depending on the experimental condition.

Inhibitors

Stimulation experiments with N2A cells were carried out under the following conditions: culture medium only, phosphate buffered saline (PBS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+, PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ (PBSC; all PAN-Biotech) or the inhibitors 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), CGP37157 (CGP), lidocaine (lid), ruthenium red (RR; all Cayman Chemical Company, USA), Cyclosporine A (CspA) or ryanodine (Ry; both Enzo Lifesciences, USA) in culture medium. Ryanodine and 2-APB were also used in combination. All inhibitors were stored in a stock solution in DMSO at −20 °C, except for RR, which was prepared in culture medium on the day of experiment.

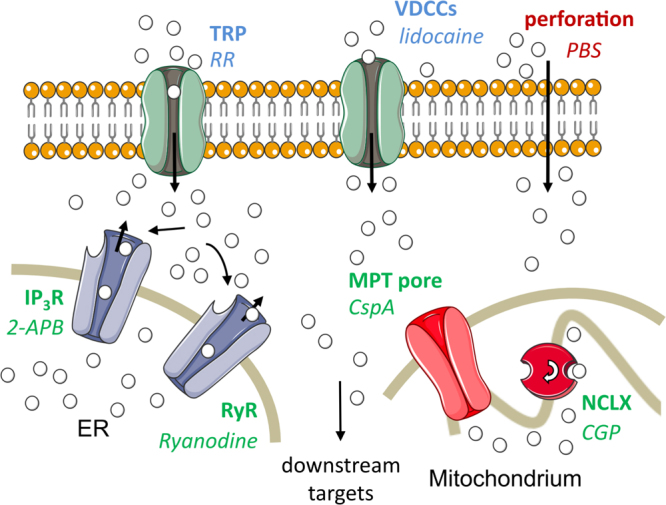

All experiments including inhibitors were conducted at a radiant exposure of 25 mJ/cm2. Table 1 gives an overview of the compounds, their final concentration and mode of action. Figure 2 gives a summary of the calcium pathways and the interfering substances.

Table 1.

Summary of experimental conditions, compound concentrations and cellular targets.

| Compound | Abbr. | Conc. | Cellular target | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| culture medium | medium | — | — | Physiological condition |

| PBS w/o Ca2+, Mg2+ | PBS | — | — | Absence of extracellular Ca2+ |

| PBS w/ Ca2+, Mg2+ | PBSC | — | — | Control for PBS |

| 2-Aminoethoxy-diphenyl borate | 2-APB | 75 µM | IP3-receptors in the ER membrane43 | Also interferes with some TRP channels44 |

| Ryanodine | Ry | 50 µM | Ryanodine receptors in the ER membrane45 | Also used in combination with 2-APB (50 µM Ry + 100 µM 2-APB) |

| CGP37157 | CGP | 20 µM | Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+-exchanger46 | |

| Ruthenium Red | RR | 100 µM | Heat-activated TRP channels47 | Also blocks intracellular channels, but does not cross the cell membrane48 |

| Lidocaine | Lid | 100 µM | Voltage-dependent sodium channels49 | Sodium currents during an action potential would activate voltage-dependent calcium channels50 |

| Cyclosporine A | CspA | 5 µM | mitochondrial membrane permeability transition pore35,36 |

Experiments were designed to inhibit specific pathways of cellular calcium signaling as well as study the overall impact of extracellular calcium.

Figure 2.

Overview of calcium pathways assessed in this study. Mechanisms of Ca2+ transport are given in bold, the respective interfering substance in italics. Intracellular pathways are denoted in green, transport across the cell membrane in blue and non-physiological mechanisms (i.e. cell perforation) in red. In the case of lidocaine, the substance does not interfere directly with the VDCCs but with voltage-dependent sodium channels, which would in turn activate the VDCCs. Calcium ions (white spheres) can be transported to the cytoplasm from the outside medium or intracellular sources, using both physiological and pathophysiological pathways. The MPT pore is closed under physiological conditions. Membrane channels of the ER can be triggered via a positive feedback loop which induces calcium-induced calcium release. TRP, transient receptor potential channels; VDCCs, voltage dependent calcium channels; IP3R, inositol trisphosphate receptors; RyR, ryanodine receptors; NCLX, mitochondrial sodium calcium exchanger; ER, endoplasmic reticulum. Figure elements from Servier Medical Art (http://smart.servier.com).

MCN were tested in medium, PBS (one experiment each at 25 mJ/cm2) and PBSC (three experiments at 25 mJ/cm2, one experiment at 17, 34, 42, and 51 mJ/cm2, respectively).

Lipid peroxidation

The lipid peroxidation sensor BODIPY 581/591 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to visualize lipid peroxidation in the cell membrane caused by laser stimulation. The compound was stored at −20 °C at a concentration of 5 mM in DMSO. Cells were prepared for laser stimulation as described above, and incubated with 10 µM BODIPY 581/591 instead of Fluo 4-AM for 30 minutes at 37 °C. The dishes were then rinsed three times with PBS and the respective test medium was added. Experiments were conducted with N2A cells in culture medium (25 and 51 mJ/cm2), PBS and PBSC (51 mJ/cm2), and MCN in PBSC (51 mJ/cm2), both with and without AuNP. Maximum radiant exposure was chosen to ensure a visible reaction. In its non-oxidized form, BODIPY 581/591 emits red light at 590 nm. Upon oxidation, the emission peak shifts to 520 nm22. Due to strong photobleaching by the laser, lipid peroxidation could not be visualized by tracking the fluorescence decrease of the red emitting form. Instead, the fluorescence increase of the green emitting form was used to assess oxidation events using the same setup as described above.

Data analysis

Images were analyzed with Fiji (ImageJ v.2.3523,24). For each cell, the mean gray value was calculated at each time point. Signals recorded after laser stimulation were normalized to baseline fluorescence values. Peak change in fluorescence (max ∆F/F0) and the time from laser pulse to peak fluorescence (time to peak) were recorded for each cell. Outliers in each experiment were detected using the interquartile range method. Values that were not included in the interval

| 1 |

were excluded from analysis unless noted otherwise. Presence or absence of PI-influx was determined by before/after imaging. Proportions that are given without a margin of error were calculated from the pooled data set.

Data analysis and visualization was performed with R (v.3.3.225).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

General calcium response

The general signature of the calcium response was quantified to assess the overall response of the cells under physiological conditions in vitro. The magnitude of the response and its time course give a first indication of the underlying mechanism.

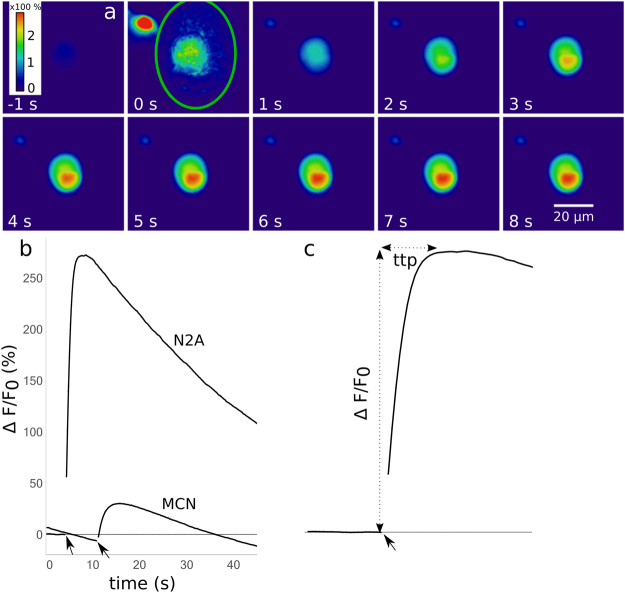

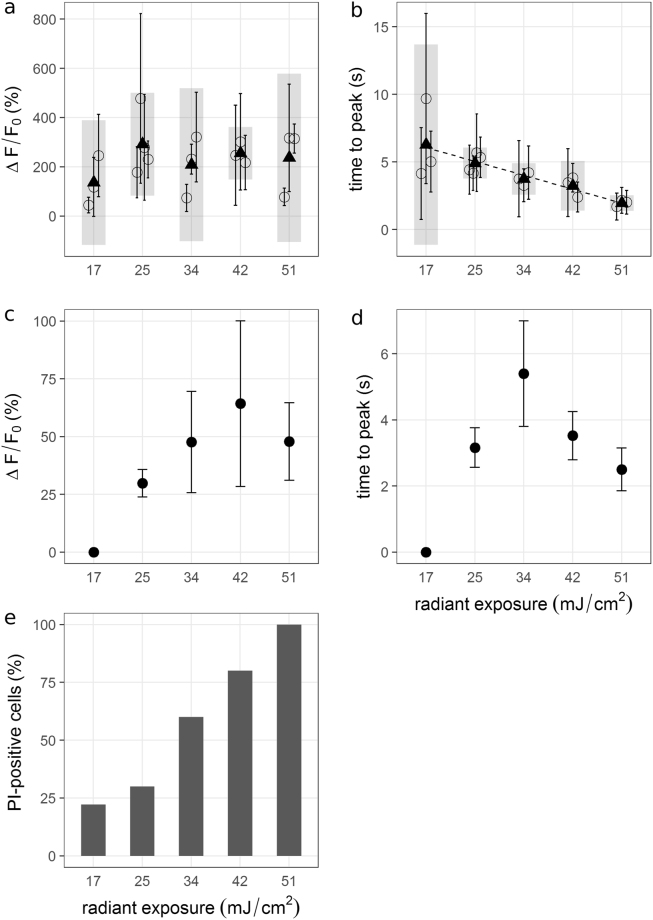

Cells that were not pre-treated with AuNP never showed an increase in Fluo 4 fluorescence in response to the laser stimulus. In the presence of AuNP, N2A cells in culture medium (without inhibitors) displayed a fluorescence increase by 100–400% within five to ten seconds, with an average increase of 200%. MCN showed no calcium response in culture medium, but a fluorescence increase by 20–60% (avg. 44%) in PBSC on the same timescale. Qualitatively, the calcium trace was highly reproducible in both cell types. Representative calcium responses are depicted in Fig. 3. The most frequently observed signature (Fig. 3b), which was recorded from 84% of stimulated N2A cells (outliers included), consisted of an immediate rise to a peak value, followed by a slower decay. To assess the impact of photobleaching, images were taken intermittently once every 60 s over 5 minutes. This mode of imaging avoided constant illumination of the fluorescent dye. The fluorescence signal remained stable, suggesting that the decay as depicted in Fig. 3b occurred mainly due to photobleaching. Occasionally (<4% of cells), the laser pulse did not evoke a fast response, but a slower rise that did not peak within observation time (30–90 s). Figure 4 shows the extent of the calcium response and its timescale depending on radiant exposure for N2A cells (a, b) and MCN (c, d). For values >17 mJ/cm2, the strength of the calcium response did not depend on the radiant exposure. The proportion of activated cells was consistently high for those values (80–100%). For N2A cells, there was a negative correlation between radiant exposure and time to peak (p < 0.001). Cells from the same experiment were pooled to account for variation between dishes. The respective mean values were averaged for each radiant exposure to estimate the overall mean (see Fig. 4b). The resulting regression line is given by

where He is the radiant exposure. Radiant exposure accounted for 57.4% of variability in mean time to peak values (R2 = 0.5738). Perforation of the cell membrane during stimulation was assessed by PI-influx. The proportion of PI-positive cells increased with radiant exposure (Fig. 4e). No distinction could be made between PI-positive and negative cells concerning the features of the calcium response, i.e. its shape and values for magnitude of peak and time to peak, except for a larger variation of ∆F/F0 of PI-positive cells (see Fig. 5d). The following experiments that included an inhibitor were conducted at 25 mJ/cm2. At this value, a high probability of activation was observed together with a relatively low probability of perforation.

Figure 3.

(a) Image series of a cell undergoing laser stimulation. The stimulus was placed at 0 s, and images were recorded at 5 fps. The green line at 0 s outlines the laser spot. A second cell (red spot at 0 s) was located in the vicinity of the spot, but not evaluated. The sequence shows the Fluo 4 intensity 1 s before the stimulus and up to 8 s afterwards. Fluorescence increase (%) is color coded. Maximum fluorescence was reached after approx. 6 s. (b) Representative depictions of the most frequently observed calcium signatures in N2A cells and MCN, respectively. Arrows indicate where the laser stimulus was placed. The respective frame was excluded from quantification, resulting in a gap in the graphs. (c) Illustration of the measurements taken for quantitative evaluation. Maximum increase in fluorescence (ΔF/F0) was measured relative to the fluorescence values before laser stimulation. Time to peak (ttp) was defined as the time in s from the laser pulse to the peak value.

Figure 4.

∆F/F0 and ttp values from N2A (a,b) and MCN (c,d) versus radiant exposure. (a,b) Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for each experiment with n = 10 cells (circles + error bars). Black triangles are averages of the respective means per radiant exposure and grey bars are the associated 95%-confidence intervals. While there is no visible trend in ∆F/F0 values, time to peak decreased with increasing radiant exposure. (c,d) Mean values and standard deviations were calculated from one experiment with n = 10 cells. Larger values for radiant exposure tended to yield larger peak fluorescence values, but also resulted in larger variation. Time to peak values do not show a clear trend. MCN were not activated at 17 mJ/cm². (e) The proportion of PI-positive N2A cells (pooled) increased with radiant exposure.

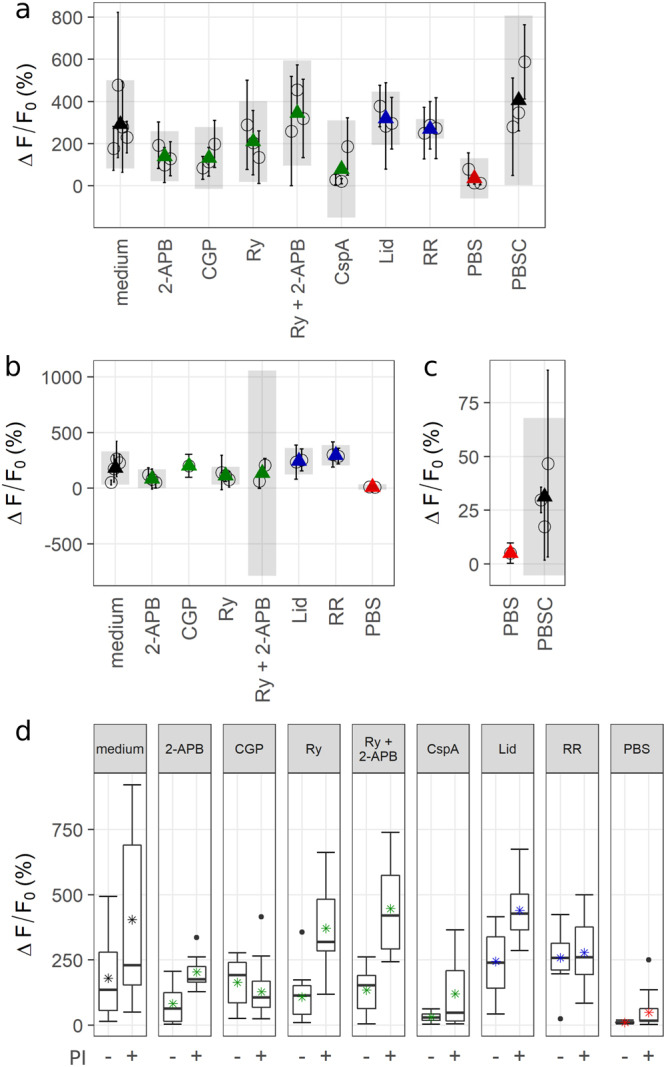

Figure 5.

(a) Maximum ∆F/F0 values of N2A cells plotted by condition. Mean values (circles) and standard deviations were calculated per experiment and averaged for each condition (triangles). Colors refer to the targeted mechanism of calcium transport (see Fig. 2). Grey bars are 95%-confidence intervals of averaged means. Cells in the absence of Ca2+ or treated with 2-APB, CGP or CspA exhibited a decreased fluorescence maximum. (b) Maximum ∆F/F0 values of PI-negative cells. Only experiments with n ≥ 3 responding PI-negative cells were considered. Occurrence of PI-influx gives implications about membrane perforation. A decrease of fluorescence values by CGP is no longer observable. (c) Peak fluorescence values of MCN plotted by condition. Absence of extracellular Ca2+ markedly decreased the calcium transients. (d) PI-negative (−) and positive (+) N2A cells pooled by condition. Some inhibitors caused a distinct determination between PI-positive and negative cells.

Inhibitor studies

Stimulation experiments were repeated with cells under different conditions. Inhibitors were employed to interfere with cellular calcium pathways (see methods section). All results presented in this section were obtained at a radiant exposure of 25 mJ/cm2.

Absence of extracellular calcium (Ca2+-free PBS) had the largest impact on ∆F/F0. Figure 5 (a,c) shows the average change in fluorescence for each experiment divided by experimental condition. When PBS was used instead of culture medium, N2A cells displayed a markedly reduced calcium signal. The same was observed for MCN in PBS compared to PBSC. The inhibitors CGP, ryanodine and especially CspA appeared to decrease the overall calcium response in N2A cells. PI influx was evaluated to assess membrane damage, as membrane perforation constitutes a way for Ca2+ to enter the cell independently of its inherent pathways. When only PI-negative cells are considered, cells treated with 2-APB or ryanodine displayed a weaker calcium response than cells that were treated only with culture medium (Fig. 5b). In CspA, the number of responding PI-negative cells per experiment was too low (<3) to calculate an average value for ∆F/F0. A comparison of peak fluorescence values of all PI-positive and negative cells is depicted in Fig. 5d. In the presence of 2-APB, ryanodine or both, cells exhibited a markedly stronger response if PI-influx occurred as well. Without inhibitors, PI-positive cells exhibit a larger variation, but the overall increase of peak fluorescence values is less pronounced. Time to peak does not show considerable variation (data not shown).Apart from the quantitative measurements, the different experimental conditions had an impact on the shape of the calcium signature in N2A cells, implying different mechanisms, kinetics, or both. Representative depictions of the different shapes and a summary of their occurrence by condition are given in Fig. 6. At a radiant exposure of 25 mJ/cm2, 61% of N2A cells in culture medium displayed a normal calcium response as shown in Fig. 3a, while 15% were not activated by the laser stimulus. Overall, cells in PBS deviated the most from the normal calcium signature, which was observed in only 10% of targeted cells. 35.5% experienced a second increase after a first peak, and 42% showed a merge. The remaining 9.5% represent outliers in time to peak. The highest proportion of non-responding cells is found among those treated with CspA (46%). Averaged across the whole data set, N2A cells showing a normal calcium response experienced a mean fluorescence increase of ∆F/F0 = 301 ± 187%. If the first peak was followed by a second rise, the mean peak value was 23 ± 25.5%. Where the immediate rise directly merged into a slower increase, the estimated average peak value was 58 ± 66.3%. PI-positive and negative cells appeared to be distributed evenly across the different types of calcium traces.

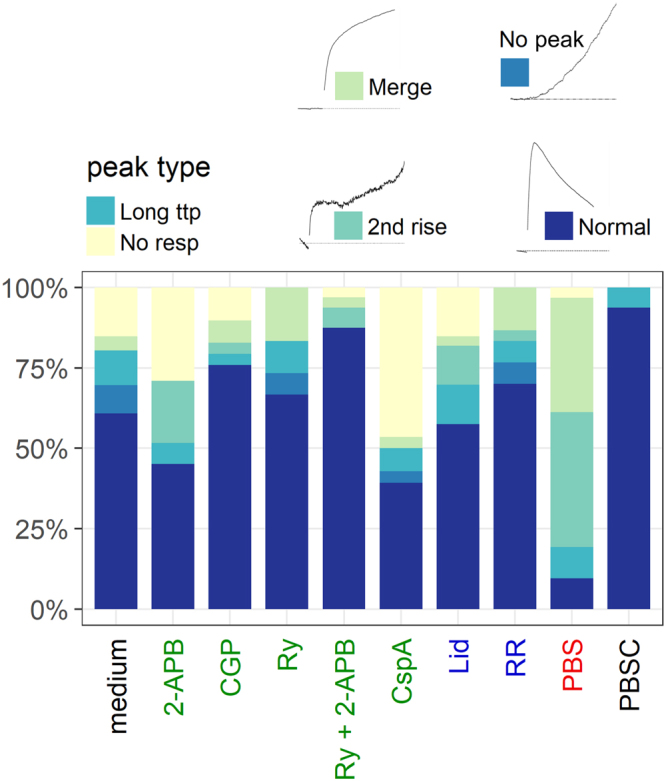

Figure 6.

Summary of different calcium signatures in N2A cells by condition. Label colors refer to the targeted mechanism of calcium transport (see Fig. 2). Representative depictions of the different calcium signatures are shown for reference. Long ttp describes cells for which the time to peak did not fall in the respective experiment’s interquartile range and that were therefore categorized as outliers. Under certain conditions, the normal calcium signature was observed less frequently. In PBS, 77.5% of cells showed either a merge or a second rise. 46% of cells in CspA exhibited no response.

Notably, MCN only showed a second fluorescence increase when kept in PBS (33.3%). All other cells displayed a normal calcium trace. A slow onset followed by a linear rise (no peak) was never observed.

Lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation in the cell membrane was investigated with a fluorescent lipid peroxidation sensor (BODIPY). Oxidation events in the membrane constitute stress signals for the cell and are often a result of excessive ROS production in the cell26.

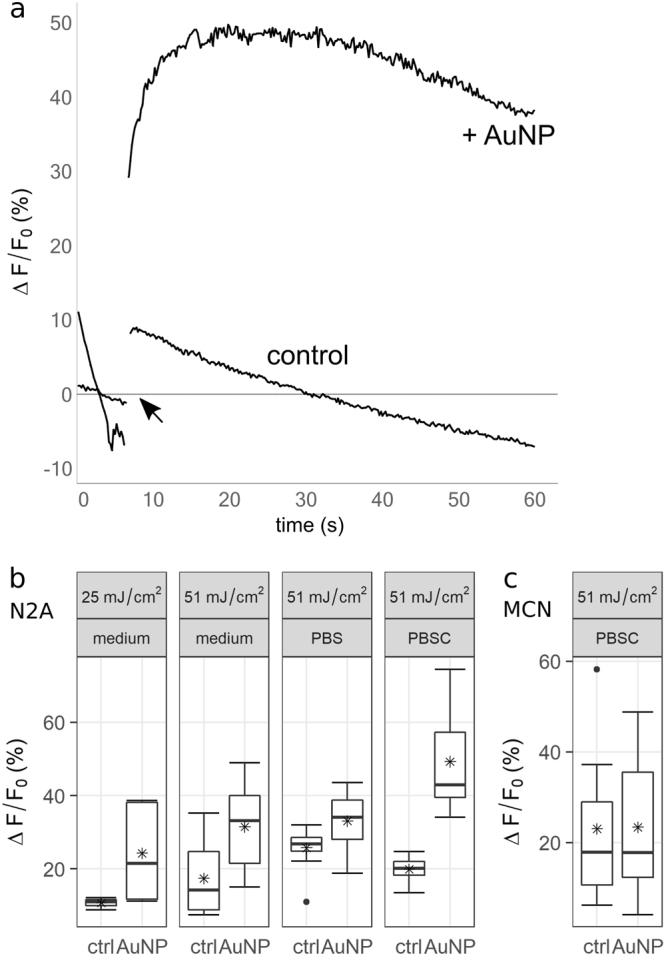

In the absence of AuNP, the laser stimulus alone evoked a fast increase of BODIPY fluorescence at 520 nm in the majority of cells (96.4%). However, cells that were pre-treated with AuNP showed a markedly stronger and slower increase under all experimental conditions (culture medium, PBS, PBSC), indicating a stronger oxidation process. Figure 7 illustrates the obtained fluorescence signals and the resulting ∆F/F0 values of the green emitting form of BODIPY 581/591. The decrease in fluorescence is likely to be the result of photobleaching. No differences became apparent that could be attributed to the different media or the radiant exposure. Notably, the effect was considerably smaller in MCN. Moreover, fluorescence spontaneously increased in eight N2A cells in PBS, i.e. the onset of the increase was not immediately connected to the laser pulse. These spontaneous events occurred both in the presence and absence of AuNP, after a laser-induced fluorescence increase.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence signals and peak fluorescence values for the green-emitting (oxidized) form of BODIPY 581/591 after laser stimulation. Control experiments were performed without gold nanoparticles. (a) Representative traces of fluorescence increase over time in N2A cells after laser stimulation with and without AuNP. In the presence of nanoparticles, the dye’s fluorescence increase was both faster and more pronounced. (b,c) In N2A cells, ∆F/F0 values increased in the presence of AuNP. No distinction can be made by power. PBSC might however strengthen the oxidizing effect. Lipidperoxidation in MCN was only assessed at 51 mJ/cm². In these cells, the oxidation by the laser alone appears to be of a similar magnitude as in the presence of AuNP.

Discussion

Our study shows that a short laser pulse in the presence of gold nanoparticles evokes a substantial calcium response in a neuronal cell line as well as in primary cortical neurons. These cellular reactions have the following key characteristics: 1) Their calcium signature is highly reproducible; 2) peak cytosolic calcium concentrations are reached within five to ten seconds; 3) radiant exposure above a certain threshold does not influence peak values, but is negatively correlated with time to peak; 4) in the absence of extracellular calcium, the calcium response has a lower amplitude and is often followed by a secondary increase of cytosolic calcium.

Ca2+ is an important messenger in the cellular stress response and can be both a consequence and a source of cell stress13,27. The immediate reaction and the magnitude of the cells’ response to a laser stimulus clearly indicate that laser treatment inflicts considerable stress upon the cells. Since the reaction was absent in AuNP-free control cells, the effect can be attributed to the interactions between the excited nanoparticles and the cell membrane. As a consequence of these interactions, membrane perforation can occur depending on radiant exposure, as was demonstrated by influx of PI or other small molecules in this and previous studies18–20 (Fig. 4e). The strength of the stressor, i.e. the increase in radiant exposure, was reflected in the decreasing time to peak.

The overall time course of the calcium signal and the lack of an effect of the inhibitor lidocaine exclude action potentials as the main underlying cause. The calcium trace expected from electrophysiological activity reaches its maximum considerably faster, on a millisecond timescale28. The smooth and reproducible rise of cytosolic calcium contradicts the expectations from a burst of action potentials, were fast calcium transients add up to a rather irregular pattern29.

It has been shown before that upon membrane perforation, a volume exchange between a cell and the surrounding medium takes place15,30. This exchange was described to be initially fast and to slow down with time. It has therefore been hypothesized that calcium flux through transient membrane pores might be a main source of strong calcium responses like those observed in the present study15,30. Cells in calcium-free PBS still showed calcium signals in response to laser stimulation, proving the involvement of at least one intracellular source. Those signals were however noticeably weaker and often altered in shape in comparison to cells in culture medium (Figs 5, 6). To assess the role of calcium influx following membrane perforation, a thorough analysis of the whole data set (738 N2A cells, 169 MCN) was performed.

In PI-negative cells, the inhibitors 2-APB and ryanodine, both of which target calcium channels in the ER-membrane, appeared to decrease the amplitude of the calcium response (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, both inhibitors caused a clear distinction between peak calcium values of PI-positive and negative cells (Fig. 5d). The propidium ion that is responsible for the nucleotide staining of perforated cells is considerably larger than the hydrated Ca2+ ion (1.5 nm31 compared to approx. 412 pm32). Therefore, Ca2+ might enter the cell through membrane pores even if no PI signal is detectable. It has been argued however, that small membrane pores constitute a large energy barrier for positively charged ions which would hinder rapid flux through such defects33. Since the immediate calcium response saturated within a few seconds and the calcium responses of PI-positive and negative N2A cells generally exhibited the same features, it seems unlikely that the immediate calcium response is caused primarily by Ca2+ influx through membrane defects.

It has been demonstrated before that plasmon excitation of gold nanoparticles in contact with a cellular membrane causes perforation18–20. The resulting holes are large enough for small molecules like proteins, RNA or dyes to enter, as is the case in the present study. The respective cells showed good viability in the previous studies, where illumination time was shorter. The overall stable phenotype for minutes after laser stimulation of cells in the present study suggests that even after a 40 ms laser pulse, membrane perforation is only transient. A collapse of stimulated cells was not observed.

The decrease of peak values by the inhibitors of intracellular Ca2+ pathways, CspA, 2-APB and ryanodine, support the hypothesis that intracellular calcium release is the key initial response. During a typical calcium response (Fig. 3a), fluorescence increased by about 250% more, on average, than in cases where the initial rise was followed by a second increase. The latter case was particularly often observed in PBS (Fig. 6). This two-component calcium response can therefore be considered inherent to the cell: An acute stress signal, represented by laser stimulation of the gold nanoparticles in contact with the cell membrane, evokes Ca2+ outflow from the ER. This outflow is initially fast, and might transition to a slower, more sustained Ca2+ release. In some cases, the fast phase was omitted and the stimulus evoked only a slow, linear calcium outflow. Such slow kinetics of Ca2+ release from the ER have been described before as a response to oxidative stress34. If the initial response is strong enough however, the slow phase is no longer observed – possibly because it is overshadowed by the strong calcium signal. The large increase in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is likely to stem from various sources. Of the tested inhibitors, only CspA strongly decreases the calcium signal. Together with the aforementioned lack of variability of calcium signatures in culture medium, this leads us to hypothesize the involvement of the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition pore (mMPTP), which is blocked by CspA35,36. This megachannel spans both mitochondrial membranes and opens in response to high levels of mitochondrial stress, caused, amongst other stressors, by calcium overload. When the initial rise of cytosolic calcium is strong enough, large amounts of calcium are sequestered by the mitochondria, which in turn undergo membrane permeability transition. This is reflected by the observations that 2-APB and ryanodine can decrease the calcium signal when no substantial influx from the surrounding medium occurs, i.e. in PI-negative cells (Fig. 5b). Only CspA consistently decreases the signal almost to levels of cells in Ca2+-free PBS (Fig. 5a). Influx from the extracellular space might still take place, but calcium flow through the mMPTP is hindered. Next to the opening of the megachannel, mitochondrial calcium overload leads to a disruption of the membrane potential and subsequent ATP consumption14, ROS production37 and mitochondrial swelling and possibly ruptures37,38.

Integrating all information gained from our observations (magnitude, time course, shape and responsiveness to modulators of the calcium response) and extensive comparisons with the available literature allow us to present conclusive evidence that gold nanoparticle mediated laser stimulation of a neuronal cell line constitutes a potent stressor for a cell, inducing Ca2+ release from the ER, opening of the mMPTP and thereby a sustained increase of cytosolic calcium concentrations. Extracellular calcium entering through membrane defects plays a role in potentiating the initial stress signal and calcium overload of the mitochondria, but is not the primary source of rising cytosolic calcium.

Notably, MCN never experience an increase of intracellular calcium at a comparable extent as N2A cells. While various factors complicate a direct comparison, it is possible that different cell types possess different levels of susceptibility to the stressor that is the laser stimulus. While the mechanisms underlying the hypothesized stress response are universal, the extent of their activation might vary across cell types and their environments. This is also reflected by the lack of MCN activation in their culture medium.

Stimulating cells stained with BODIPY 581/591 showed that in the presence of AuNP, the laser stimulus caused membrane lipids to oxidize (Fig. 7). The process of oxidation usually includes formation of lipid radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS)39,40. These reactive molecules are known to damage numerous cellular macromolecules if present at high levels. They constitute an unspecific stress signal and might represent a way for the cell to sense lipid oxidation or molecule breakdown occurring in the vicinity of irradiated AuNP. Dejeans et al.34 demonstrated that oxidative stress causes a slow, sustained calcium release from the ER, agreeing with the continually increasing Ca2+ levels sometimes observed after an initial fast response or instead of a fast response (see Fig. 6, “2nd rise” and “No peak”). This further reinforces our hypothesis: if the initial fast response is not present or is particularly weak, mitochondrial Ca2+ levels don’t rise high enough to cause opening of the mMPTP and subsequent high cytosolic calcium levels. Instead, a milder form of ER stress emerges, as is triggered by oxidative stress34. This is consistent with the observation that in MCN, a weaker calcium response occurs in combination with a less pronounced lipid peroxidation process. Whether or not a cell experiences the profound and potentially fatal calcium stress response as described above might therefore depend on the membrane’s susceptibility for lipid damage caused by the external stimulus. This susceptibility is likely to be altered by the cell’s immediate environment – i.e. adjacent cells, tissue biology or medium composition.

Conclusion

In this study, we highlighted for the first time the consequences that gold nanoparticle mediated laser stimulation can have for neuronal cells. The lack of studies concerned with the metabolic impact of laser stimulation made it necessary for us to first collect a large amount of unbiased data reflecting (patho-) physiological processes triggered by the stimulus. Visualizing calcium flux and lipid peroxidation in a large number of cells allowed us to formulate a coherent hypothesis: Irradiation of AuNP at their plasmon resonance frequency triggers calcium release from the ER, often accompanied and potentiated by calcium inflow through a perforated membrane. The excess calcium is sequestered by the mitochondria, and in response to calcium overload, permeability transition sets in. Subsequent studies will be necessary to specifically determine the involvement of the mMPTP. Regardless of the source however, calcium overload of a cell generally has adverse effects, especially if repeated stimulation leads to chronic cell stress. Extensive impacts on cell physiology and metabolism are the consequences, linked for example to different neurodegenerative diseases41,42. In in vivo applications, a healthy biological interface is crucial for functionality of a neuroimplant. Our results highlight the problematic nature of a safe translation of this application into living organisms, although the specific cell response might vary in complex tissues. Since the general approach allows for cell stimulation with high spatiotemporal precision it could prove to be a valuable tool in cell biology, enabling for example the study of long-term effects of stressors affecting only single cells in a network, cellular priming by triggering a calcium signal, or the complex interplay of physiological and pathophysiological pathways.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the DFG Cluster of Excellence EXC 1077/1 “Hearing4all” and supported by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) project-ID 57245147 sponsored by funds of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). S. Kalies and A. Heisterkamp received funding from the German Research Foundation through the Cluster of Excellence REBIRTH (DFG EXC62/3).

Author Contributions

S.J. and D.H. designed the study; S.J. conducted the experiments with technical assistance from S.K.; S.J. analysed the data and wrote the paper; P.H., M.T., A.H. and T.R. provided general assistance. All authors have read and approved the final submission.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Davidson TJ, Mogri M, Deisseroth K. Optogenetics in Neural Systems. Neuron. 2011;71:9–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fino E, et al. RuBi-Glutamate: Two-photon and visible-light photoactivation of neurons and dendritic spines. Front. Neural Circuits. 2009;3:2. doi: 10.3389/neuro.04.002.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warther D, et al. Two-photon uncaging: New prospects in neuroscience and cellular biology. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2010;18:7753–7758. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro MG, Homma K, Villarreal S, Richter C-P, Bezanilla F. Infrared light excites cells by changing their electrical capacitance. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:736. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho-de-Souza JL, et al. Photosensitivity of neurons enabled by cell-targeted gold nanoparticles. Neuron. 2015;86:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly LK, Coronado E, Zhao LL, Schatz GC. The Optical Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size, Shape, and Dielectric Environment. J Phys Chem. 2003;107:668–677. doi: 10.1021/jp026731y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavoie-Cardinal F, Salesse C, Bergeron É, Meunier M, De Koninck P. Gold nanoparticle-assisted all optical localized stimulation and monitoring of Ca2+ signaling in neurons. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:20619. doi: 10.1038/srep20619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paviolo C, Haycock JW, Cadusch PJ, Mcarthur SL, Stoddart PR. Laser exposure of gold nanorods can induce intracellular calcium transients. J. Biophotonics. 2014;7:761–765. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201300043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pustovalov VK, Smetannikov AS, Zharov VP. Photothermal and accompanied phenomena of selective nanophotothermolysis with gold nanoparticles and laser pulses. Laser Phys. Lett. 2008;5:775–792. doi: 10.1002/lapl.200810072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kültz D. Molecular and Evolutionary Basis of the Cellular Stress Response. Dx.Doi.Org.Proxy.Library.Vanderbilt.Edu. 2004;67:225–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.103635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clapham DE. Calcium Signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ermak G, Davies KJ. Calcium and oxidative stress: from cell signaling to cell death. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:713–721. doi: 10.1016/S0161-5890(01)00108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulda, S., Gorman, A. M., Hori, O. & Samali, A. Cellular stress responses: Cell survival and cell death. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2010 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Duchen MR. Contributions of mitochondria to animal physiology: from homeostatic sensor to calcium signalling and cell death. J. Physiol. 1999;516(Pt 1):1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.001aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalies S, et al. Investigation of biophysical mechanisms in gold nanoparticle mediated laser manipulation of cells using a multimodal holographic and fluorescence imaging setup. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farah N, et al. Holographically patterned activation using photo-absorber induced neural-thermal stimulation. J. Neural Eng. 2013;10:56004. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/5/056004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evangelopoulos ME, Weis J, Krüttgen A. Signalling pathways leading to neuroblastoma differentiation after serum withdrawal: HDL blocks neuroblastoma differentiation by inhibition of EGFR. Oncogene. 2005;24:3309–3318. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinemann D, et al. Gold Nanoparticle Mediated Laser Transfection for Efficient siRNA Mediated Gene Knock Down. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinemann D, et al. Delivery of proteins to mammalian cells via gold nanoparticle mediated laser transfection. Nanotechnology. 2014;25:245101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/25/24/245101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalies S, et al. Characterization of the cellular response triggered by gold nanoparticle–mediated laser manipulation. J. Biomed. Opt. 2015;20:115005. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.20.11.115005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schomaker M, et al. Characterization of nanoparticle mediated laser transfection by femtosecond laser pulses for applications in molecular medicine. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2015;13:10. doi: 10.1186/s12951-014-0057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drummen GPC, Van Liebergen LCM, Op den Kamp JAF, Post JA. C11-BODIPY581/591, an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent lipid peroxidation probe: (Micro)spectroscopic characterization and validation of methodology. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;33:473–490. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00848-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schindelin J, Rueden CT, Hiner MC, Eliceiri KW. The ImageJ ecosystem: An open platform for biomedical image analysis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2015;82:518–529. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–82. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2017).

- 26.Ayala, A., Muñoz, M. F. & Argüelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: Production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Kass GEN, Orrenius S. Calcium signaling and cytotoxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999;107:25–35. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smetters D, Majewska A, Yuste R. Detecting Action Potentials in Neuronal Populations with Calcium Imaging. Methods. 1999;18:215–221. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaksi E, Friedrich RW. Reconstruction of firing rate changes across neuronal populations by temporally deconvolved Ca2+ imaging. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:377–383. doi: 10.1038/nmeth874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumgart J, et al. Quantified femtosecond laser based opto-perforation of living GFSHR-17 and MTH53 a cells. Opt. Express. 2008;16:3021–31. doi: 10.1364/OE.16.003021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowman AM, Nesin OM, Pakhomova ON, Pakhomov AG. Analysis of plasma membrane integrity by fluorescent detection of Tl + uptake. J. Membr. Biol. 2010;236:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9269-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell, A. K. Intracellular Calcium. (John Wiley & Sons, 2014). 10.1002/9781118675410.

- 33.Leontiadou H, Mark AE, Marrink S-J. Ion transport across transmembrane pores. Biophys. J. 2007;92:4209–4215. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dejeans N, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium release potentiates the ER stress and cell death caused by an oxidative stress in MCF-7 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;79:1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Broekemeier KM, Dempsey ME, Pfeiffer DR. Cyclosporin A is a potent inhibitor of the inner membrane permeability transition in liver mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:7826–7830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S. Role of the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition in cell death. Apoptosis. 2007;12:835–840. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng T-I, Jou M-J. Oxidative stress caused by mitochondrial calcium overload. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1201:183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deniaud a, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces calcium-dependent permeability transition, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:285–299. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buege JA, Aust SD. Microsomal Lipid Peroxidation. Methods Enzym. 1978;52:302–310. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(78)52032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finkel T, Holbrook N. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szydlowska K, Tymianski M. Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwak S, Weiss JH. Calcium-permeable AMPA channels in neurodegenerative disease and ischemia. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2006;16:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diver JM, Sage SO, Rosado JA. The inositol trisphosphate receptor antagonist 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate (2-APB) blocks Ca2 + entry channels in human platelets: cautions for its use in studying Ca2+ influx. Cell Calcium. 2001;30:323–329. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bootman MD, et al. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) is a reliable blocker of store-operated Ca2+ entry but an inconsistent inhibitor of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release. FASEB J. 2002;16:1145–1150. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0037rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, Hamilton SL. Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:1–21. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dittami GM, Rajguru SM, Lasher RA, Hitchcock RW, Rabbitt RD. Intracellular calcium transients evoked by pulsed infrared radiation in neonatal cardiomyocytes. J. Physiol. 2011;589:1295–1306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.198804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clapham DE, Runnels LW, Strübing C. The TRP ion channel family. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:387–396. doi: 10.1038/35077544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feldmeyer D, Melzer W, Pohl B, Zöllner P. A possible role of sarcoplasmic Ca2+ release in modulating the slow Ca2+ current of skeletal muscle. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1993;425:54–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00374503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leung YM, Wu BT, Chen YC, Hung CH, Chen YW. Diphenidol inhibited sodium currents and produced spinal anesthesia. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:1147–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Catterall WA. Voltage-Gated CalciumChannels. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:1–24. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.