Abstract

Background

Life partnerships other than marriage are rarely studied in childhood cancer survivors (CCS). We aimed (1) to describe life partnership and marriage in CCS and compare them to life partnerships in siblings and the general population; and (2) to identify socio-demographic and cancer-related factors associated with life partnership and marriage.

Methods

As part of the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (SCCSS), a questionnaire was sent to all CCS (aged 20–40 years) registered in the Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry (SCCR), aged <16 years at diagnosis, who had survived ≥5 years. The proportion with life partner or married was compared between CSS and siblings and participants in the Swiss Health Survey (SHS). Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with life partnership or marriage.

Results

We included 1,096 CCS of the SCCSS, 500 siblings and 5,593 participants of the SHS. Fewer CCS (47%) than siblings (61%, P < 0.001) had life partners, and fewer CCS were married (16%) than among the SHS population (26%, P > 0.001). Older (OR = 1.14, P < 0.001) and female CCS (OR = 1.85, <0.001) were more likely to have life partners. CCS who had undergone radiotherapy, bone marrow transplants (global PTreatment = 0.018) or who had a CNS diagnosis (global PDiagnosis < 0.001) were less likely to have life partners.

Conclusion

CCS are less likely to have life partners than their peers. Most CCS with a life partner were not married. Future research should focus on the effect of these disparities on the quality of life of CCS.

Keywords: childhood cancer survivors, cohort study, life partnership, marriage, questionnaire survey, siblings

Introduction

Childhood cancer may affect a person’s ability to find a life partner. Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are less likely to be married than their peers [1–8]. CCS who had radiation therapy [1,2,5,6,9], and those who survived tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) are at high risk for remaining single [1,10–12].

Most studies that investigated life partnership in CCS limited their definition to marriage [4–7,9], but cohabitation and other partnership arrangements are increasingly common in Switzerland, and age of marriage is trending upward. In Switzerland, the proportion of those who marry at <30 years has decreased from 71% in men and 82% in women in 1970, to 28% in men and 43% in women in 2008 [13]. More and more couples live together without marrying (4% in 1980, 11% in 2000) [14].

Studies rarely investigate both married and unmarried life partnerships in CCS, and their results have been inconsistent. These earlier studies either do not reflect current demographic trends [10,12], were conducted in cultures very different from Swiss culture (Japan) [15], were hospital-based [16], lacked comparison groups [3] or used proxy measures like household composition to assess unmarried life partnerships [17].

Using the population-based Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (SCCSS), our goal was to describe the current state of life partnerships and marriage in CCS in Switzerland. All forms of life partnership were included, regardless of marital status or sexual orientation. We aimed to (1) describe the age- and gender-stratified proportion of CCS who live in a life partnership or are married, compared to siblings and the general population; and (2) to identify socio-demographic and cancer-related factors associated with life partnership and marriage. Multivariable logistic regressions were used to identify socio-demographic and cancer-related factors associated with life partnership and marriage.

Materials and Methods

The Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (SCCSS)

The SCCSS is a population-based long-term follow-up study of all patients registered in the Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry (SCCR), diagnosed 1976–2005, aged <16 years, who survived >5 years [18]. The SCCR includes all children and adolescents in Switzerland diagnosed with leukemia, lymphoma, CNS tumors, malignant solid tumors or Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) before age 21 years [19]. In 2007–2010 addresses of eligible CCS were traced and an extensive questionnaire was sent [18]. Non-responders received another questionnaire and were then contacted by phone. The questionnaires were similar to those used in US and UK childhood cancer survivor studies [20,21]. Additionally questions on health behaviors and socio-demographic measures from the Swiss Health Survey (SHS) 2007 [22] and the Swiss Census 2000 [23] were added. Ethics approval was granted through the general cancer registry of the SCCR (The Swiss Federal Commission of Experts for Professional Secrecy in Medical Research) and a non-obstat statement from the ethics committee of the canton of Bern was obtained.

Comparison Groups

The results from CCS were compared to two different groups: siblings of CCS and a random sample of the general population (SHS).

Siblings

In the questionnaire, CCS were asked to list their siblings. In 2010–2011 CCS were asked for consent to contact their siblings and to provide us with their address. Siblings received the same questionnaire as CCS, without questions related to cancer history. Siblings who did not respond received a second copy of the questionnaire after 4–6 weeks, but were not contacted by phone.

The Swiss Health Survey

The SHS is a telephone survey of a representative sample of the Swiss resident population, conducted at 5-year intervals. It asks questions in a computer-assisted phone interview about health and related subjects (details are described elsewhere) [24]. Households are randomly selected from each canton, and one person is randomly selected in each household. There were 18,760 interviewed persons in the sample (response rate 66%) [22]. For this study all respondents to the 2007 SHS study, aged 20–40 years were included.

Outcome Measures: Life Partnership and Marriage

Life partnership

CCS and siblings were asked in the questionnaire if they were then living with a life partner or were married. Participants who answered “yes” were classed as having a life partnership (life-partnered). For the SHS population, information on life partnership was not available.

Marriage

Civil status was assessed using the following categories: “single”, “married”, “widowed”, and “divorced” in CCS and siblings, and “single”, “married”, “widowed”, “divorced”, “separated”, “civil union”, “dissolved civil union”, and “other” in the SHS population. Participants who answered with “married” or “civil union” were coded as being married.

Explanatory Variables: Socio-Demographic and Clinical Data

We chose explanatory variables that predated life partnership or marriage. The following socio-demographic variables were assessed for CCS, siblings, and the SHS population: age at survey; gender; migration background; language region of Switzerland (German, French, or Italian); and education. A participant had a migration background if he or she fulfilled one of the following criteria: not born in Switzerland; no Swiss citizenship at birth; at least one parent with no Swiss citizenship. Education was divided into two categories: low educational level included compulsory schooling only (≤9 years) and vocational training; high educational level included higher vocational training, college or university degree.

For CCS, cancer-related variables were extracted from the SCCR. This included diagnostic group [25], treatment modalities (chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy, bone marrow transplantation), age at diagnosis and relapse status.

Statistical Analysis

Standardization of comparison groups

Our analysis included all CCS, their siblings and the SHS aged 20–40 years at time of survey. The sibling and SHS population had higher percentage of women and older persons than did the CCS population. Migrants, French- and Italian-speaking persons were more frequent in the SHS population and less frequent in the sibling population than they were in the CCS group (Supplemental Table I). To standardize the sibling and SHS population for these different distributions, weights for both populations were computed. CCS were combined with siblings in one data set, and CCS with the SHS population in another. Multivariable logistic regression was used on the two combined datasets, were being a control was the outcome. Thus appropriate weights were computed and assured that the weighted marginal distribution of age, gender, language region, and migration background was identical in CCS and the control population. CCS weight was set to one. These weights were applied in all analyses resulting in a standardized sibling and SHS population.

Analysis

First frequencies between CCS and the two comparison groups were compared using chi-squared test. Gender and age stratified relative risks (RR) were calculated for being in a life partnership or married and compared CCS to each of the other groups. Likelihood ratio tests were used to determine the interaction between gender and study group and between age and study group. Then explanatory variables were fitted in uni- and multivariable regressions to determine associations with life partnership and marriage. Global P-values were calculated with Wald tests and used likelihood ratio tests to determine interaction. P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed with Stata, version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

We contacted 1,561 CCS and 845 siblings. Of those, 1,187 CCS (76%) and 500 siblings (59%) returned our questionnaire. In the CCS group, 91 participants returned an abridged version of the questionnaire that did not include questions on life partnership and marriage; they could not be included in this study. The SHS population provided data of 5,593 participants who were eligible for our study.

Among CCS, non-participants were more likely than participants to be male (P < 0.001), to live in a French or Italian speaking region (P = 0.014), to have been diagnosed with lymphoma, CNS tumor, soft tissue sarcoma, germ cell tumor, LCH or other malignant tumor (global P = 0.003), and were less likely to have had chemotherapy (P < 0.001; Supplemental Table II).

The mean age of participating CCS was 26.6 years (SD = 5.3); 53% were males, 27% had migration background, and 76% were from a German-speaking region of Switzerland (Table I). The population of siblings and participants from SHS were standardized for these four socio-demographic measures. Siblings reported higher educational level and the SHS lower educational level than the CSS group. Leukemia (37%) was the most common cancer among CCS, followed by lymphoma (20%) and CNS tumors (12%); 12% had had a relapse. As treatment 85% had received chemotherapy, 67% surgery, 40% radiotherapy, and 4% bone marrow transplantation. Mean age at diagnosis was 7.8 years (SD = 4.8).

Table I. Characteristics of CCS, their Siblings, and the Population-Based SHS.

| CCS (N = 1,096) |

Siblingsa (N = 500) |

SHSa (N = 5,593) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%b) | n (%b) | P-valuec | n (%b) | P-valued | |

| Socio-demographic conditions | |||||

| Age at study | |||||

| 20–<25 years | 454 (41) | 196 (39) | 2,348 (42) | ||

| 25–<30 years | 325 (30) | 156 (31) | 1,638 (29) | ||

| 30–<35 years | 201 (18) | 95 (19) | 1,022 (18) | ||

| 35–40 years | 116 (11) | 53 (11) | n.a.a | 585 (10) | n.a.a |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 578 (53) | 261 (52) | 3,015 (54) | ||

| Female | 515 (47) | 239 (48) | n.a.a | 2,578 (46) | n.a.a |

| Migration backgrounde | |||||

| Yes | 296 (27) | 124 (25) | n.a.a | 1,491 (27) | n.a.a |

| Language region | |||||

| German | 830 (76) | 384 (77) | 4,239 (76) | ||

| French | 229 (21) | 98 (20) | 1,129 (20) | ||

| Italian | 37 (3) | 18 (4) | n.a.a | 225 (4) | n.a.a |

| Educational levelf | |||||

| Low | 605 (56) | 186 (39) | 3,698 (71) | ||

| High | 466 (44) | 289 (61) | <0.001 | 1,504 (29) | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Having a life partner | |||||

| No | 572 (53) | 196 (39) | |||

| Yes | 510 (47) | 302 (61) | <0.001 | n.a.g | n.a.g |

| Civil status | |||||

| Single | 893 (83) | 389 (78) | 4,013 (72) | ||

| Married | 170 (16) | 100 (20) | 1,440 (26) | ||

| Divorced | 18 (2) | 7 (1) | 130 (2) | ||

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.112 | 7 (<1) | <0.001 |

| Cancer-related conditions | |||||

| Diagnosis (ICCC-3) | |||||

| Leukemia | 400 (37) | n.a.i | n.a.i | ||

| Lymphoma | 218 (20) | ||||

| CNS | 129 (12) | ||||

| Neuroblastoma | 42 (4) | ||||

| Retinoblastoma | 23 (2) | ||||

| Renal tumor | 63 (6) | ||||

| Hepatic tumor | 7 (1) | ||||

| Bone tumor | 61 (6) | ||||

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 60 (6) | ||||

| Germ cell tumor | 31 (3) | ||||

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | 44 (4) | ||||

| Other tumorsh | 18 (2) | ||||

| Treatmentsj | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 931 (85) | n.a.i | n.a.i | ||

| Surgery | 736 (67) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | 433 (40) | ||||

| Bone marrow transplantation | 43 (4) | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | |||||

| 0–5 years | 423 (39) | n.a.i | n.a.i | ||

| >5–10 years | 279 (25) | ||||

| >10–16 years | 394 (36) | ||||

| Relapse | |||||

| No | 955 (87) | ||||

| Yes | 141 (13) | n.a.i | n.a.i | ||

CNS, central nervous system; ICCC-3, International Classification of Childhood Cancer—Third Edition [25]; n, number; n.a., not applicable/not available. Percentages are based upon available data for each variable.

Standardized on age, gender, migration background, and language region according to the CCS population;

Column percentages are given;

P-value calculated from chi-square statistics comparing CCS to siblings;

P-value calculated from chi-square statistics comparing CCS to SHS;

Migration background was defined if a participant fulfilled one of the following criteria: not born in Switzerland, no Swiss citizenship from birth on, at least one parent with no Swiss citizenship;

Low educational level includes compulsory training and vocational training. High educational level includes upper secondary and university education;

Information on life partner was not available for SHS;

Other malignant epithelial neoplasms, malignant melanomas, and other or unspecified malignant neoplasms;

Information on former cancer disease is not applicable for siblings and SHS;

Each participant could have had more than one treatment.

Life Partnership and Marriage

Among CSS, 47% (510/1,082) were life-partnered, compared to 61% (302/498) of siblings (P < 0.001; Table I). Similarly, a smaller percentage of CSS were married (16%, 170/1,081) than among siblings (20%, 100/496) and the general population (26%, 1,440/5,590). These differences remained after adjusting for socio-demographic factors. CCS were less likely to be life-partnered than their siblings (OR = 0.58, P < 0.001) and less likely to be married (compared to siblings: OR = 0.73, P = 0.066; compared to the SHS population: OR = 0.50, P < 0.001; Table III).

Table III. Socio-Demographic Predictors of Life Partnership/Marriage in CCS and Comparison Groups in Logistic Multivariable Models.

| Life partnership | CCS |

Siblingsc |

SHSc |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95%-CI | P-valueb | ORa | 95%-CI | P-valueb | ORa | 95%-CI | P-valueb | |

| Aged | 1.14 | 1.11–1.17 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.12–1.24 | <0.001 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | n.a. | ||||||

| Female | 1.85 | 1.40–2.38 | <0.001 | 2.22 | 1.39–3.53 | 0.001 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Migration backgroundee | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | n.a. | ||||||

| Yes | 1.03 | 0.76–1.38 | 0.912 | 0.49 | 0.27–0.88 | 0.017 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Language | |||||||||

| German | 1.00 | 1.00 | n.a. | ||||||

| French or Italian | 0.42 | 0.31–0.58 | <0.001 | 0.74 | 0.40–1.35 | 0.328 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Educational level | |||||||||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | n.a. | ||||||

| High | 1.27 | 0.98–1.66 | 0.073 | 0.80 | 0.50–1.28 | 0.348 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Model including: | CCS and siblingsf | CCS and SHSf | |||||||

| Study group | |||||||||

| Comparison group | 1.00 | n.a. | |||||||

| CCS | 0.58 | 0.45–0.75 | <0.001 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |||

| Marriage | |||||||||

| Aged | 1.31 | 1.25–1.36 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 1.30–1.47 | <0.001 | 1.25 | 1.23–1.27 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Female | 1.41 | 0.96–2.08 | 0.081 | 2.39 | 1.32–4.32 | 0.004 | 1.74 | 1.48–2.04 | <0.001 |

| Migration backgrounde | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.25 | 0.82–1.91 | 0.303 | 0.94 | 0.46–1.94 | 0.875 | 1.96 | 1.64–2.33 | <0.001 |

| Language | |||||||||

| German | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| French or Italian | 1.20 | 0.77–1.87 | 0.414 | 0.91 | 0.43–1.91 | 0.801 | 1.36 | 1.15–1.59 | <0.001 |

| Educational level | |||||||||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| High | 0.92 | 0.63–1.36 | 0.685 | 0.87 | 0.48–1.56 | 0.642 | 0.69 | 0.58–0.83 | <0.001 |

| Model including: | CCS and siblingsf | CCS and SHSf | |||||||

| Study group | |||||||||

| Comparison group | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| CCS | 0.73 | 0.52–1.02 | 0.066 | 0.50 | 0.41–0.61 | <0.001 | |||

Odds ratio (OR) for marriage and life partnership;

Global P-value calculated withWald test;

Standardized on age, gender, migration background, and language region according to the CCS population;

Continuously measured in years;

Migration background was defined if a participant fulfilled one of the following criteria: not born in Switzerland, no Swiss citizenship from birth on, at least one parent with no Swiss citizenship;

Logistic multivariable model including CCS and respective comparison group, controlled for socio-demographic factors (age, gender, migration background, language region, educational level).

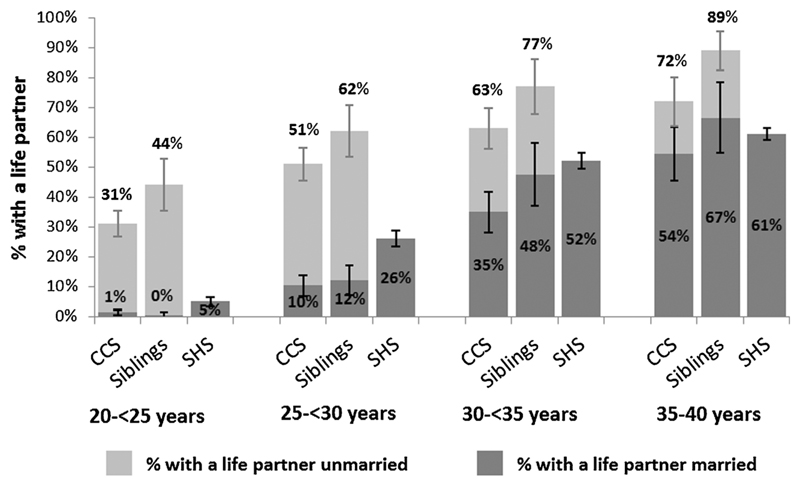

Age adjusted analysis

CCS, siblings, and participants of the SHS were more likely to be life-partnered or married as they aged (Fig. 1). As age increased, the proportion of married CCS increased more than the proportion of married SHS participants, and became comparable in the oldest age group: RR35-<40years = 0.89 (P = 0.175; Table II). When CCS were compared to siblings, the same trend in life partnership or marriage was not evident.

Fig. 1.

Proportions with a life partner in CCS and comparison groups stratified by age with 95% confidence intervals. The numbers on top of the bars represent the total proportion with a life partner (married and unmarried). Sibling and SHS population are standardized on age, gender, migration background, and language region according to the CCS population. Data for being unmarried with a life partner were not available for the SHS population.

Table II. Life Partnership/Marriage in CCS and Comparison Groups Stratified by Age and Gender.

| Life partnership CCS compared to siblingsa |

Marriage CCS compared to siblingsa |

Marriage CCS compared to SHSa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRb | 95% CI | P-valuec | RRb | 95% CI | P-valuec | RRb | 95% CI | P-valuec | |

| Overall | 0.78 | 0.70–0.86 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.63–0.98 | 0.031 | 0.61 | 0.53–0.71 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||||||||

| 20–<25 years | 0.71 | 0.56–0.90 | 0.005 | 2.78 | 0.33–23.14 | 0.334 | 0.26 | 0.11–0.61 | 0.002 |

| 25–<30 years | 0.82 | 0.69-0.98 | 0.029 | 0.85 | 0.51–1.43 | 0.545 | 0.39 | 0.28–0.55 | <0.001 |

| 30–<35 years | 0.82 | 0.70–0.97 | 0.018 | 0.74 | 0.55–0.99 | 0.040 | 0.67 | 0.55–0.82 | <0.001 |

| 35–<40 years | 0.71 | 0.63–0.80 | <0.001 | 0.82 | 0.64–1.05 | 0.110 | 0.89 | 0.75–1.05 | 0.175 |

| Test for interaction | |||||||||

| Age x CCS | 0.904d | 0.676d | <0.001d | ||||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Males | 0.78 | 0.66–0.93 | 0.005 | 0.98 | 0.69–1.41 | 0.921 | 0.75 | 0.61–0.92 | 0.005 |

| Females | 0.77 | 0.68–0.88 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.48–0.85 | 0.002 | 0.50 | 0.41–0.62 | <0.001 |

| Test for interaction | |||||||||

| Gender x CCS | 0.864d | 0.169d | 0.390d | ||||||

Standardized on age, gender, migration background, and language region according to the CCS population;

Risk ratios (RR) for marriage and life partnership comparing CCS to the respective comparison group;

P-value calculated from chi-square statistics comparing CCS and siblings; CCS and SHS, respectively;

P-value calculated from likelihood ratio test.

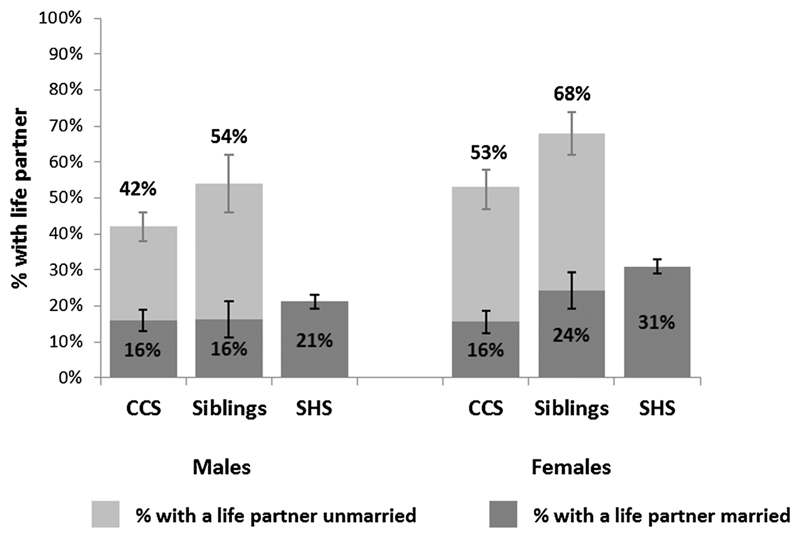

Gender adjusted analysis

Within the CCS group, more women were life-partnered (53%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 48–59%) than men (42%, CI: 38–46%). The proportion of married men and women was the same for CCS (Fig. 2). Female CCS were less likely to be life-partnered or married than their counterparts in the comparison groups. Male CCS were less likely to be life-partnered than siblings, and less likely to be married than the SHS participants. However male CCS and male siblings married in similar proportions (RRmale = 0.98, P = 0.921; Table II).

Fig. 2.

Proportions with a life partner in CCS and comparison groups stratified by gender with 95% confidence intervals. The numbers on top of the bars represent the total proportion with a life partner (married and unmarried). Sibling and SHS population are standardized on age, gender, migration background, and language region according to the CCS population. Data for being unmarried with a life partner were not available for the SHS population.

Predictors for Life Partnership and Marriage

In univariable models the association between socio-demographic and cancer-related variables was tested and the outcomes of life partnership and marriage were used for CCS, siblings, and the SHS sample (Supplemental Table III). All socio-demographic variables were significant for at least one of the three groups in one of the two outcomes, except educational level, which was unevenly distributed among the three groups. We thus decided to take all socio-demographic factors into the multivariable model. In CCS, all cancer-related variables were significant for at least one of the two outcomes. Relapse was not significantly associated, but was taken into the final model so that results would be comparable to other studies.

Socio-demographic predictors

All socio-demographic factors were tested in three multivariable models. Both CCS and siblings with a life partner tended to be older and female, but CCS were more likely to live in the German-speaking region of Switzerland and siblings were less likely to have migration background (Table III). Married CCS and siblings were older than unmarried CCS and siblings. Female siblings were more likely to be married than male siblings. The married SHS population tended to be older, female, have a migration background, live in the French- or Italian-speaking region of Switzerland and have low educational level.

Cancer-related predictors

In the multivariable model cancer-related predictors were tested in the CCS population, while controlling for socio-demographic factors (Table IV). Having a life partner was associated with treatment (global P = 0.018) and cancer diagnosis (global P < 0.001). CCS who had undergone radiotherapy (OR = 0.76) or bone marrow transplantation (OR = 0.79) were less likely to be life-partnered. Compared to CCS of leukemia, those CCS with CNS tumor (OR = 0.23) were less likely to be life-partnered. CCS of retinoblastoma, germ cell tumors, neuroblastoma, and LCH showed a similar tendency. Age at diagnosis and relapse were not significantly associated with life partnership. Cancer-related factors were not associated significantly with marriage. CCS of CNS tumors tended to be less likely to be married (OR = 0.43, global P = 0.601) compared to CCS with other diagnoses.

Table IV. Cancer-Related Predictors of Life Partnership/Marriage in CCS in Two Logistic Multivariable Models.

| Life partnershipa |

Marriagea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORb | 95% CI | P-valuec | ORb | 95% CI | P-valuec | |

| Diagnosis (ICCC-3) | ||||||

| Leukemia | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Lymphoma | 0.94 | 0.64–1.40 | 1.04 | 0.59–1.81 | ||

| CNS | 0.23 | 0.12–0.41 | 0.43 | 0.18–1.08 | ||

| Neuroblastoma | 0.64 | 0.30–1.33 | 1.13 | 0.34–3.75 | ||

| Retinoblastoma | 0.52 | 0.19–1.43 | 0.56 | 0.07–4.52 | ||

| Renal tumor | 1.29 | 0.71–2.33 | 0.86 | 0.31–2.34 | ||

| Hepatic tumor | 0.96 | 0.16–5.59 | 1.41 | 0.13–15.27 | ||

| Bone tumor | 1.25 | 0.68–2.31 | 2.01 | 0.85–4.71 | ||

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 1.49 | 0.79–2.78 | 0.97 | 0.41–2.30 | ||

| Germ cell tumor | 0.56 | 0.24–1.29 | 0.78 | 0.23–2.62 | ||

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | 0.84 | 0.41–1.74 | <0.001 | 1.31 | 0.46–3.67 | 0.601 |

| Treatmentd | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Radiotherapy | 0.76 | 0.55–1.05 | 0.86 | 0.54–1.36 | ||

| Surgery | 1.90 | 1.03–3.49 | 1.19 | 0.45–3.13 | ||

| Bone marrow transplantation | 0.79 | 0.38–1.64 | 0.018 | 0.38 | 0.09–1.53 | 0.501 |

| Age at diagnosis (in years) | ||||||

| 0–5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| >5–10 | 1.08 | 0.75–1.55 | 1.06 | 0.62–1.82 | ||

| >10–16 | 1.12 | 0.78–1.62 | 0.826 | 1.03 | 0.60–1.77 | 0.979 |

| Relapse | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 0.83 | 0.54–1.27 | 0.387 | 0.52 | 0.26–1.04 | 0.064 |

CNS, central nervous system; ICCC-3, International Classification of Childhood Cancer—Third Edition [25].

Standardized on age, gender, migration, language region, and educational level;

Odds ratio (OR) for marriage and life partnership;

Global P-value calculated with Wald test;

Chemotherapy may include surgery; radiotherapy: may include surgery and/or chemotherapy; bone marrow transplantation: may include surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy.

Discussion

Most CCS with a partner were not married: 47% of CCS were life-partnered, but only 16% were married. Fewer CCS had life partners than did siblings. The proportion of married CSS was lower than in the general population. Cancer-related factors were associated with life partnership but not significantly with marriage.

Comparison with Other Studies and Interpretation of Results

We found no other study that directly compared married and unmarried life partnership between CCS, siblings, and the general population. Our results and those of earlier studies indicate that the proportion of the CSS and comparison group members who are life-partnered or married varies substantially across different countries. In our study 47% of CCS are life-partnered, in contrast to 61% of siblings (RR = 0.78). This resembles results from Denmark (CCS: 47%, controls: 60%), were household composition was used as a proxy for life partnership [17]. But a hospital-based study in the Netherlands found only 19% of male and 37% of female CCS to be life-partnered, in contrast to 46% in the male and 61% in the female comparison group [16]. In our study 16% of CCS were married, in contrast to 20% of siblings (RR = 0.78) and 26% of the general population (RR = 0.61). These results are, again, comparable to those of the study in Denmark (CCS: 19%, controls: 25%) [17]. The proportion of married CSS in the United States was much higher: 43% of CCS were married. Compared to the age- and gender-adjusted general US population only CCS of hematologic malignancies treated with radiation were significantly less likely to be married (CCS: 44%, general population: 52%) [9]. Cultural differences between countries may explain some of the differences in proportions married or life-partnered among CCS and comparison groups.

Socio-demographic factors affected proportions of life partnership and marriage. The proportion of married CCS increased with age, and reached a number that did not differ statistically from the SHS sample in those aged ≥35 years. CCS did not differ significantly from siblings regarding marriage but siblings were more often life-partnered. Like others, we found that male CCS were less likely to be life-partnered than female CSS [16]. Unlike other reports, we did not find male CCS less likely to be married than female CCS [1,2].

In CSS, those living in the French or Italian region of Switzerland were less likely to be life-partnered, but not less likely to be married. We do not know the effect of regional differences on the likelihood that CCS will marry of find a life partner. No other studies were found that analyze the association between country regions and life partnership in CCS.

Highly educated SHS participants were less likely to marry than their less educated peers. In CCS and siblings the trend was similar. In the United Kingdom, Frobisher et al. [1] also found similar results. Because it takes longer to complete higher degrees, people who spend more years in school or training may marry and found families late. A study from the SCCSS suggests that CCS might also take longer to reach their final educational achievement than the general population [26], and this might encourage CSS to delay marriage.

Cancer-related predictors in CCS were associated with life partnership but not significantly with marriage. Other studies showed that for CCS of CNS tumors the risk of being unmarried [1–3] or without a life partner [16,17] was higher compared to CCS with other diagnosis. We confirmed this for the outcome of life partnership. Others have noted that radiotherapy is a risk factor for marriage in the United Kingdom and the United States [1,2]. We found the same association for the outcome of life partnership. Additionally those treated with bone marrow transplants were less likely to have a life partner than those who received other treatments. In their study, Felder-Puig et al. [27] found strong unfulfilled needs for a love life in 26 CCS who were treated with bone marrow transplants. Treatment with bone marrow transplant could be included as a factor in research on life partnership in CCS. Relapse and young age at diagnosis are risk factors for marriage and life partnership in the literature [2,16]. We did not find an association with age at diagnosis or relapse and life partnership or marriage, only a weak tendency into the same direction.

Limitations and Strengths

Compared to other childhood cancer cohorts [20,28], the SCCSS has a relatively small sample size [18]. This creates the risk that significance of results will be underestimated. Siblings responded at a lower rate than CCS, so the sample might not accurate represent the whole sibling population. Data on life partnership were only available for CCS and siblings so the difference in life partnership could not be measured between CCS and the general population (SHS). Finally, it remains unknown how the duration, quality and number of life partnerships in CSS compares to siblings or the general population.

Selection bias plays a minor role because of the high response of the population-based sample of Swiss CCS (76%). Because the original data of two comparison groups were used, we captured a broad snapshot of life partnership and marriage in CCS, their siblings and the general population. Weighting siblings and SHS participants maximized comparability to the CCS cohort. We also went beyond surveying marriage proportions, and determined the proportion of CSS with life partners. This improved our ability to draw sound conclusions about life partnerships regardless of sexual orientation in a young cohort in which most participants were still unmarried.

Conclusion

Our results suggest some directions for future research. We suggest that bone marrow transplantation could be included as a factor in future research on life partnership in CCS. Marriage turned out to be no valid proxy for life partnership in Switzerland, and we suspect this is true in other countries as well. Our expanded definition of life partnership can be adopted for future studies, to capture the broadest possible picture of CSS partnerships. We also encourage longitudinal studies that track the changing status of CSS relationships, and allow for more complex analysis of the relationship between life partnership and quality of life.

We have reported that CCS are less likely to be married than the general population, and discovered they are also less likely to be in life partnerships than their siblings. How these disparities affect CSS’ quality of life has yet to be determined.

Supplementary Material

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all CCS and their siblings for participating in our survey, and the Swiss Federal Statistical Office for providing data for the Swiss Health Survey 2007. We thank the study team of the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (Erika Brantschen Berclaz, Micòl Gianinazzi, Julia Koch, Fabienne Liechti), the data managers of the Swiss Paediatric Oncology Group (Claudia Anderegg, Nadine Beusch, Rosa-Emma Garcia, Franziska Hochreutener, Friedgard Julmy, Nadine Lanz, Heike Markiewicz, Genevieve Perrenoud, Annette Reinberger, Renate Siegenthaler, Verena Stahel, and Eva Maria Tinner), and the team of the Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry (Vera Mitter, Elisabeth Kiraly, Marlen Spring, Christina Krenger, Priska Wölfli). We also thank Ben Spycher for his statistical advice and Kali Tal for her editorial assistance. This study was financially supported by Cancer League Aargau (www.krebsliga-aargau.ch), Bernese Cancer League (www.bernischekrebsliga.ch), and Cancer League Zurich (www.krebsligazh.ch), the Swiss Cancer League (KLS-02783-02-2011), Swiss Bridge and Stiftung zur Krebsbekämpfung. GM and SE were funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (GM: Ambizione Fellowship grant PZ00P3_121682/1 and PZ00P3-141722, SE: MD-PhD grant 323630-133897; www.snf.ch) and Cancer Research Switzerland (SE: MD-PhD grant 02606-06-2010; www.krebsforschung.ch). The work of the Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry is supported by the Swiss Paediatric Oncology Group, Kinderkrebshilfe Schweiz, Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen und -direktoren and Stiftung für krebskranke Kinder Regio Basiliensis.

Grant sponsor: Swiss Cancer League; Grant number: KLS-02783-02-2011; Grant sponsor: Swiss National Science Foundation; Grant numbers: PZ00P3_121682/1; PZ00P3-141722; 323630-133897; Grant sponsor: Cancer Research Switzerland; Grant number: 02606-06-2010; Grant sponsors: Cancer League Aargau, Bernese Cancer League, Cancer League Zurich, Swiss Paediatric Oncology Group, Kinderkrebshilfe Schweiz, Swiss Bridge, Stiftung zur Krebsbekämpfung, Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen und -direktoren, and Stiftung für krebskranke Kinder Regio Basiliensis

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Nothing to declare.

References

- 1.Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, et al. Long-term population-based marriage rates among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Britain. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:846–855. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janson C, Leisenring W, Cox C, et al. Predictors of marriage and divorce in adult survivors of childhood cancers: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2626–2635. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pivetta E, Maule MM, Pisani P, et al. Marriage and parenthood among childhood cancer survivors: A report from the Italian AIEOP Off-Therapy Registry. Haematologica. 2011;96:744–751. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.036129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurney JG, Krull KR, Kadan-Lottick N, et al. Social outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2390–2395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Long-term outcomes among adult survivors of childhood central nervous system malignancies in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:946–958. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mody R, Li S, Dover DC, et al. Twenty-five-year follow-up among survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Blood. 2008;111:5515–5523. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagarajan R, Neglia JP, Clohisy DR, et al. Education, employment, insurance, and marital status among 694 survivors of pediatric lower extremity bone tumors: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer. 2003;97:2554–2564. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laverdière C, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Long-term outcomes in survivors of neuroblastoma: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1131–1140. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crom DB, Lensing SY, Rai SN, et al. Marriage, employment, and health insurance in adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:237–245. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rauck AM, Green DM, Yasui Y, et al. Marriage in the survivors of childhood cancer: A preliminary description from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:60–63. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199907)33:1<60::aid-mpo11>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langeveld NE, Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, et al. Quality of life in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:579–600. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrne J, Fears TR, Steinhorn SC, et al. Marriage and divorce after childhood and adolescent cancer. JAMA. 1989;262:2693–2699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bundesamt für Statistik. Demografisches Porträt der Schweiz. Neuchâtel: Bundesamt für Statistik; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundesamt für Statistik. Panorama - Bevölkerung. Neuchâtel: Bundesamt für Statistik; 2013. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida Y, Honda M, Kamibeppu K, et al. Social outcomes and quality of life of childhood cancer survivors in Japan: A cross-sectional study on marriage, education, employment and health-related QOL (SF-36) Int J Hematol. 2011;93:633–644. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0843-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langeveld NE, Ubbink MC, Last BF, et al. Educational achievement, employment and living situation in long-term young adult survivors of childhood cancer in the Netherlands. Psychooncology. 2003;12:213–225. doi: 10.1002/pon.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch SV, Kejs AM, Engholm G, et al. Marriage and divorce among childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:500–505. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31822820a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuehni CE, Rueegg CS, Michel G, et al. Cohort profile: The Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1553–1564. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michel G, von der Weid NX, Zwahlen M, et al. The Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry: Rationale, organisation and results for the years 2001–2005. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:502–509. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkins MM, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, et al. The British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: Objectives, methods, population structure, response rates and initial descriptive information. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1018–1025. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A National Cancer Institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2308–2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liebherr R, Marquis J, Storni M, et al. Gesundheit und Gesundheitsverhalten in der Schweiz 2007 - Schweizerische Gesundheitsbefragung. Neuchâtel: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Germann U. Eidgenössische Volkszählung 2000 - Abschlussbericht zur Volkszählung 2000. Neuchâtel: Bundesamt für Statistik; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bundesamt für Statistik. Die Schweizerische Gesundheitsbefragung 2007 in Kürze-Konzept, Methode, Durchführung. Neuchâtel: Bundesamt für Statistik; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Lacour B, et al. International Classification of Childhood Cancer, third edition. Cancer. 2005;103:1457–1467. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuehni CE, Strippoli MP, Rueegg CS, et al. Educational achievement in Swiss childhood cancer survivors compared with the general population. Cancer. 2012;118:1439–1449. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felder-Puig R, Peters C, Matthes-Martin S, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of pediatric patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:75–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:229–239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.