Abstract

Background:

Antiasthmatic medications such as β2 agonists and corticosteroids have shown potential side effects such as increased caries risk and oral candidiasis. Studies evaluating microbial changes in adult asthmatics are very scanty in the literature. The present study aimed to evaluate the effects of asthma and its medication on cariogenic bacteria and Candida albicans in adult asthmatics.

Aim and Objectives:

Our aim was to evaluate and compare counts of Streptococcus mutans (SM) and lactobacilli in plaque and C. albicans in saliva samples of adult asthmatics with controls and during the course of medication longitudinally.

Methodology:

Samples were collected from twenty recently diagnosed asthmatic adults and twenty controls for estimation of microbial counts at baseline and at 3rd and 6th month after initiation of medication among cases.

Results:

Asthmatics at baseline had higher microbial counts than controls, but the difference was not statistically significant. Comparison between asthmatics at baseline and 3rd month after initiation of medication showed an increase in counts of SM, lactobacilli and decreased C. albicans counts though the difference was not significant. Comparison between asthmatics at baseline and 6th month and also between 3rd and 6th month showed significantly increased counts of SM. Although there was an increase in counts of lactobacilli and decreased C. albicans counts, significant results were not noted. Asthmatics showed increased microbial counts than controls overall.

Conclusion:

Asthmatics were found to have higher microbial counts than controls at baseline. Increase in SM and lactobacilli counts in asthmatics after medication emphasizes the need to monitor these patients regularly.

Keywords: Asthma, Candida albicans, colony forming units, corticosteroids, lactobacilli, microbial counts, plaque, saliva, Streptococcus mutans, β2 agonists

INTRODUCTION

Bronchial asthma is a chronic airway disorder. Very few studies evaluating the microbial changes in the oral cavity of asthmatic subjects have been reported.[1,2] β2 agonists have shown potential side effects such as hyposalivation and altered salivary composition, leading to increased caries risk.[3] Use of corticosteroids increases the risk of oral candidiasis.[4] Drug treatment in asthmatics has a stronger effect on oral health than the disease per se.[5] Evaluating microbial changes in response to disease and its treatment is necessary to emphasize oral hygiene.

The present study aimed at evaluating the effects of asthma and its medication on cariogenic bacteria and Candida albicans. Our aim was to estimate and compare counts of Streptococcus mutans (SM), lactobacilli in plaque and C. albicans in saliva samples of healthy controls and asthmatic adults before and after initiation of standard prescribed medication.

METHODOLOGY

A total number of forty subjects with twenty each in case and control groups were included in the study. Recently diagnosed twenty cases of asthmatic adults confirmed by a pulmonologist in the age range of 20–45 years, reporting to Department of Pulmonary Medicine, J.J.M. Medical College, were included in the study. An equal number of age- and sex-matched healthy volunteers were included as controls. Informed patient consent was obtained from every subject for inclusion in the study and for performing tests. A detailed case history was recorded for the cases. Institutional ethical clearance was also obtained. Individuals on long-term antibiotic therapy or any medication that would alter the oral microbial environment, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, malnourishment, obesity, denture wearers, smokers, alcoholics and individuals having decayed missing filled teeth >15 were excluded from the study.[6]

Baseline plaque and saliva samples were collected from asthmatics before the onset of standard prescribed medication. This was followed by professional oral prophylaxis and demonstration of the Bass method of brushing technique and advice on oral hygiene methods. Asthmatic patients were also advised about the appropriate use of inhalers. Asthmatic subjects were advised antiasthma medications such as beta-agonists such as formoterol (6 mcg) and corticosteroids such as budesonide (100 mcg) and methyl prednisolone (40–80 mg).

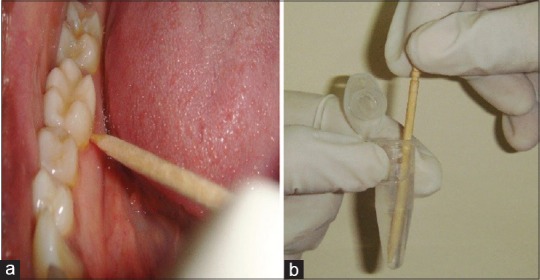

Supragingival plaque samples were collected using a sterile toothpick from cervical third of lingual surface of mandibular first or second molar of either side, and toothpick was immediately immersed in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline and carried in a vaccine carrier with ice pack to the laboratory [Figure 1a and b].

Figure 1.

Collection of plaque from the patient using wooden toothpick (a) and toothpick dipped in the phosphate buffer saline (b)

For a collection of saliva samples, subjects were advised not to eat 1 h before saliva sample collection. Subjects were asked to rinse the mouth and sit upright and to swallow existing saliva. After a minimum of 5-min rest, unstimulated whole saliva was collected by asking the subjects to spit the whole saliva into a sterile container for 5–10 min [Figure 2], and samples were then carried immediately in a vaccine carrier with ice pack to the laboratory for further processing. As far as possible sample was immediately inoculated. Subsequently, samples were collected in asthmatics at an interval of 3 months, and 6 months after, initiation of medication and microbial counts were assessed for SM, lactobacilli and C. albicans. Baseline samples of plaque and saliva were collected from age- and sex-matched controls for microbial counts. All samples were collected at 1–2 pm before lunch.

Figure 2.

Collection of saliva from the patient

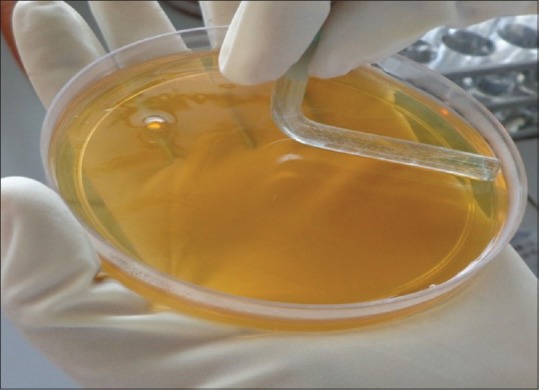

After serial dilution, a dilution of 10-1 was selected for inoculation. Fifty microliters of diluted sample was inoculated using sterile L-shaped glass rods by spread method for lawn culture [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Sample inoculation on culture plate by spread method

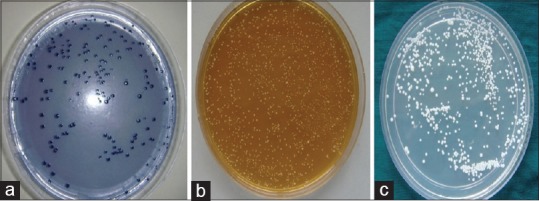

Samples were inoculated on different media as follows: samples were inoculated on mitis salivarius bacitracin agar medium (MSB) for SM [Figure 4a] and in Rogosa selective lactobacilli agar (RSL) media for lactobacilli [Figure 4b]. The MSB agar plates and RSL plates were incubated in candle jars at 37°C for 2 days anaerobically. Similarly, 50 μl of diluted sample was inoculated on Sabouraud's Dextrose Agar for C. albicans and were incubated at 37°C for 3–5 days aerobically [Figure 4c].

Figure 4.

Colonies of Streptococcus mutans on Mitis salivarius-bacitracin agar (a), lactobacilli on Rogosa selective lactobacilli agar (b) and Candida albicans on Sabouraud's Dextrose agar (c)

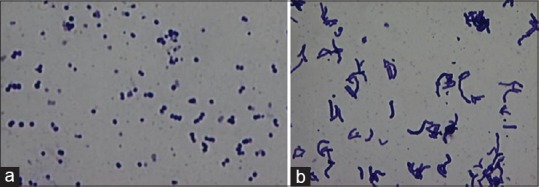

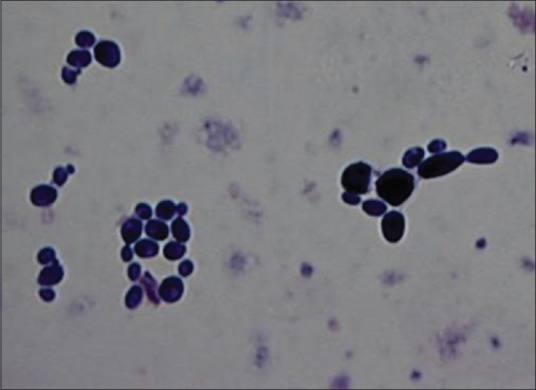

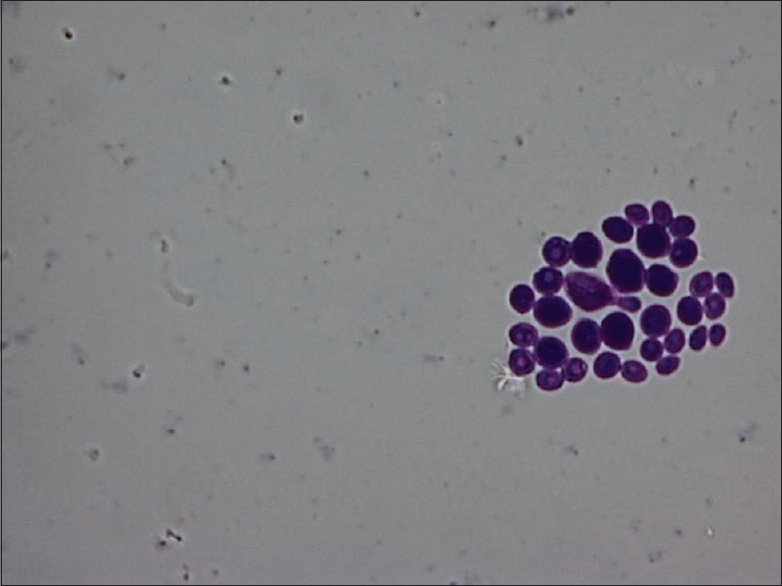

For SM, confirmation was done by characteristic colony morphology, catalase test and mannitol fermentation test. All colonies on RSL medium were considered to be lactobacilli [Figure 4b], and colony morphology was also studied. Gram's staining was done for both SM [Figure 5a] and lactobacilli [Figure 5b]. For confirmation of C. albicans, Gram's staining [Figure 6], Periodic acid–Schiff stain [Figure 7] and germ tube test were done.

Figure 5.

Gram-positive Streptococcus mutans seen in pairs and chains (Gram's stain, ×100) (a) Gram-positive lactobacilli seen in groups (Gram's stain, ×100) (b)

Figure 6.

Gram-positive Candida albicans seen in groups as yeast forms showing budding (Gram's stain, ×100)

Figure 7.

Periodic acid–Schiff-positive Candida albicans seen as yeast forms (Periodic acid–Schiff stain, ×100)

All colonies formed were counted using digital colony counter. The counts were tabulated as colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/ml). Microbial quantification was performed using the following formula:

![]()

Where X = Quantification of microbes in CFU

Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for intragroup comparison within asthmatics and Mann–Whitney test was used for intergroup comparison between asthmatics and controls.

RESULTS

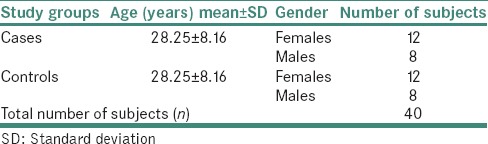

A total number of forty subjects comprising twenty asthmatics and an equal number of age- and sex-matched healthy controls with the age range of 20–45 years were included in the study. Cases were followed longitudinally for a period of 6 months [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sample distribution in the study population

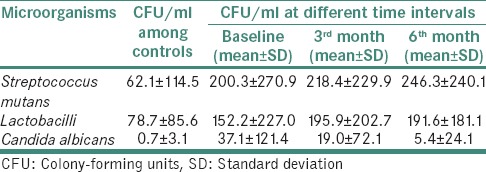

The mean CFU/ml counts of SM, lactobacilli and C. albicans among controls and asthmatics at different time intervals were as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Microbial counts in mean colony-forming units/ml among controls and asthmatics at different time intervals

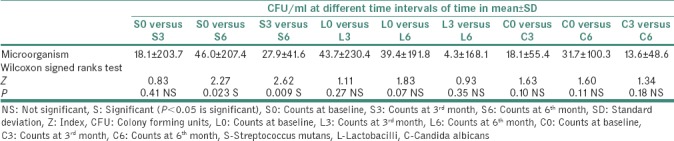

Comparison of asthmatics without medication (at baseline) and at 3rd month after initiation of medication revealed the mean difference of SM, lactobacilli and C. albicans counts as 18.1 ± 203.7, 43.7 ± 230.4 and 18.1 ± 55.4, respectively. The difference for SM (P = 0.41), lactobacilli (P = 0.27) and C. albicans (P = 0.10) counts in CFU/ml was not statistically significant [Table 3].

Table 3.

Intragroup comparison of Streptococcus mutans, Lactobacilli counts and Candida albicans counts in mean colony-forming units/ml at different time intervals among asthmatics

Comparison of asthmatics without medication (at baseline) and at 6th month after initiation of medication showed the mean difference for SM, lactobacilli and C. albicans counts to be 46.0 ± 207.4, 39.4 ± 191.8 and 31.7 ± 100.3, respectively. The mean difference of counts for SM was statistically significant (P = 0.023), whereas the difference for lactobacilli (P = 0.07) and C. albicans (P = 0.11) counts was not significant [Table 3].

Comparison of asthmatics at 3rd month after initiation of medication and asthmatics at 6th month showed the mean difference for SM, lactobacilli and C. albicans counts to be 27.9 ± 41.6, 4.3 ± 168.1 and 13.6 ± 48.6, respectively. The mean difference for SM was statistically significant (P = 0.009), whereas difference was not significant for lactobacilli (P = 0.35) and C. albicans (P = 0.18) [Table 3].

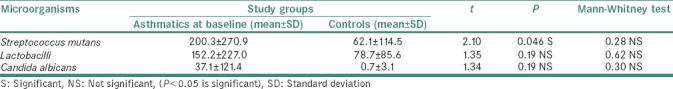

Comparison of mean microbial counts between asthmatics and controls revealed statistically insignificant result. However, SM, lactobacilli and C. albicans counts were found to be higher in asthmatics when compared to controls overall [Table 4].

Table 4.

Intergroup comparison of microbial counts in mean colony-forming units/ml between asthmatics without medication (at baseline) and controls

DISCUSSION

The present study was conducted to evaluate microbial counts in adult asthmatics when compared to healthy controls and also during the course of medication among cases. The prevalence of SM, lactobacilli (L) and C. albicans (C) in controls was 50%, 80% and 5% respectively in this study. Hirasawa and Takada[7] and Wu et al.[8] detected SM in 58.3% and 75.45% in caries-free children and adults, respectively. Sigurjóns et al. found SM in 96.7% and lactobacilli in 62% of the subjects in their study.[9] Samaranayake found the oral carriage of C. albicans in about 3%–48% of healthy adults.[10]

The prevalence of SM, lactobacilli and C. albicans was 55%, 55% and 10%, respectively, in asthmatics in the present study. Dubus et al. found 10% prevalence of C. albicans in asthmatics.[11]

When microbial counts were compared between asthmatics at baseline (without medication) and controls, though the counts were higher in cases than controls, the difference was not statistically significant. Our result could not be compared with any other published data as we could not find any other data pertaining to asthmatics before medication. It remains uncertain whether higher counts in asthmatics are due to disease per se or any other unknown factors.

Comparison of SM counts in asthmatics at baseline and 3rd month showed no difference. This could be attributed to the oral prophylaxis performed just before initiation of medication and time taken by microbes to recolonize themselves. However, comparison of SM counts at 3rd month and 6th month and also between baseline and 6th month showed statistically significant results (P = 0.009 and P = 0.023, respectively). This could be due to an increase in microbes after recolonization or in response to medication use.

Use of medications such as β2 agonists has shown to cause a reduction in salivary flow rate, altered salivary composition, reduced pH, reduced buffering capacity and increase in cariogenic bacteria which may be due to the medications containing fermentable carbohydrates and sugar.[2,4]

The decreased salivary flow and altered salivary composition may be due to other reasons other than β2 agonist use. In a study, subjects were mainly treated with inhaled corticosteroids and showed reduced salivary flow rates.[12]

In the present study, lactobacilli counts did not show a statistical difference between cases and controls though counts were higher in asthmatics. Comparison of lactobacilli counts among asthmatics at different intervals also showed no statistical difference. However, counts were increased at 3rd month and 6th month after initiation of medication compared to baseline. Possible reasons for this increase would be the use of medications containing lactose or fermentable carbohydrates and sugar causing acidic pH environment[13,14,15] and onset of root caries and deep dentinal caries which favor colonization of lactobacilli.[16,17]

Brigic et al. observed no significant difference in concentration of SM between asthmatic children (7–14 years with 2-year medication) and controls. They concluded that antiasthma drugs do not cause hyposalivation and thus do not favor increased concentration of SM.[18] On the contrary, Venkatesh observed SM to be higher in asthmatic children (5–12 years), whereas lactobacillus was similar in both the study groups[19] which is in accordance with the present study. However, our study subjects were adults.

Increased dental biofilm and salivary SM levels and no difference in lactobacilli levels were also noticed by Botelho et al. in asthmatic children (3–15 years). They observed a correlation between SM levels and treatment duration. Authors concluded that asthma should be considered as risk factor caries experience, especially in older children (11–15 years) since it increases levels of SM.[20] Children using medications three times a day and in combination with corticosteroids had increased levels of SM and lactobacilli compared to other asthmatics.[21]

A negative correlation between duration of medication and a positive correlation between duration of disease and salivary SM levels was noted in young asthmatics (6–19 years). Authors concluded that asthma through its disease status and its medication carries some risk factors for caries development in these patients.[22]

Effects of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting sympathicomimetics on dental health in adult asthmatics (20–55 years) were studied by Karova and Christoff, and they observed a significantly higher decayed, missing and filled teeth index among asthmatics compared to the controls.[23]

Stensson et al. in their study in asthmatics (18–24 years) on long duration of medication (13.5 years) concluded that initial caries was more common in asthmatics compared to the controls.[1]

Candidal counts did not show significant difference among cases and controls at baseline in the present study. Among three cases positive for candida, one presented with angular cheilitis, suggesting the presence of candidiasis in this patient. Intragroup comparison among asthmatics at different time intervals also showed no statistical difference in candidal counts. Our results were in accordance with Lenander-Lumikari et al. and Komiyama et al.[24,25] “Candidal pathogenicity depends on their ability to adhere to mucosa, to form pseudohyphae and to secrete histolytic enzymes. Furthermore, host factors such as mucosal integrity, leukocytes, macrophages, salivary components such as lactoferrin, lysosome and specific immune mechanisms both humoral and cell mediated.”[26] It also depends on spacer used, inhalation technique and oral rinse after every use of medication.[10,26] Contrary to this finding, Shaw and Edmund showed significantly increased the incidence of Candida in asthmatics treated with inhaled corticosteroids compared to controls.[27]

Our data were limited to microbial quantification as a possible indication for higher caries risk. However, analysis of salivary flow rate, composition, buffering capacity and pH should also be considered in future studies. Multifactorial etiology of dental caries is a well-established fact. Just the mere increase in microbial counts does not necessarily put asthmatics at increased caries risk. Nevertheless, the oral physiological changes and changing oral environment may also result in fluctuation of bacterial counts making it difficult to study the effects of drugs and the disease itself.[13,28]

Our study has shown that definite microbial changes do occur in asthmatics which further get modified by antiasthma medications, thus emphasizing the need for patient education on proper oral health care, technique of drug use, noncariogenic dietary regimen, fluoride supplementation and regular checkups. This would reduce oral health problems in asthmatics, thereby improving the quality of life.

CONCLUSION

Based on the present study, it can be concluded that subjects with asthma have slightly higher microbial counts than controls at baseline. Whether this points to a tendency of the disease to modify or increase the bacterial counts or is a chance occurrence needs to be studied in a larger population study. A significant increase in microbial counts of cariogenic bacteria, especially SM was found in asthma patients after initiation of medication. Although lactobacilli counts were higher after initiation of medication, results were not significant. Simultaneously, no significant change was found in the number of opportunistic candidal counts. Whether a direct cause to effect relation exists with the medication itself causing an increased bacterial count or an indirect effect of the medications on salivary function could not be ascertained in this study.

Asthmatic patients commonly face oral problems due to lack of awareness regarding oral hygiene measures. Special preventive and educational measures will be required to prevent dental caries and other oral diseases in asthmatic patients.

Limitations and future scope

Longitudinal studies at further time intervals are needed. Determining the microbial counts among controls in a corresponding time pattern as the case group could also be considered to take into account the possible physiological variations. Conducting the study with larger sample size in future can examine the effect of the disease itself rather than the treatment.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by College of Dental Sciences, Davangere.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Vishwanth G, Professor and Head, Department of General Microbiology, J.J.M. Medical College, Davangere, Karnataka, for his assistance in carrying out the study. We thank Mr. Sangam. D. K. for statistical analysis, and Mr. Mallikarjun, Mr. Manjunath and Mr. Kumar, laboratory technicians, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, Karnataka, for their technical help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stensson M, Wendt LK, Koch G, Oldaeus G, Ramberg P, Birkhed D, et al. Oral health in young adults with long-term, controlled asthma. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69:158–64. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.547516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryberg M, Möller C, Ericson T. Saliva composition and caries development in asthmatic patients treated with beta 2-adrenoceptor agonists: A 4-year follow-up study. Scand J Dent Res. 1991;99:212–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1991.tb01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellepola AN, Samaranayake LP. Inhalational and topical steroids, and oral candidosis: A mini review. Oral Dis. 2001;7:211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryberg M, Möller C, Ericson T. Effect of beta 2-adrenoceptor agonists on saliva proteins and dental caries in asthmatic children. J Dent Res. 1987;66:1404–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660082401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godara N, Godara R, Khullar M. Impact of inhalation therapy on oral health. Lung India. 2011;28:272–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.85689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hugoson A, Koch G, Slotte C, Bergendal T, Thorstensson B, Thorstensson H, et al. Caries prevalence and distribution in 20-80-year-olds in Jönköping, Sweden, in 1973, 1983, and 1993. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:90–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028002090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirasawa M, Takada K. A new selective medium for Streptococcus mutans and the distribution of S. mutans and S. sobrinus and their serotypes in dental plaque. Caries Res. 2003;37:212–7. doi: 10.1159/000070447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu H, Fan M, Zhou X, Mo A, Bian Z, Zhang Q, et al. Detection of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus on the permanent first molars of the mosque people in China. Caries Res. 2003;37:374–80. doi: 10.1159/000072171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigurjóns H, Magnúsdóttir MO, Holbrook WP. Cariogenic bacteria in a longitudinal study of approximal caries. Caries Res. 1995;29:42–5. doi: 10.1159/000262038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samaranayake LP, MacFarlane TW. Hypothesis: On the role of dietary carbohydrates in the pathogenesis of oral candidosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;27:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubus JC, Marguet C, Deschildre A, Mely L, Le Roux P, Brouard J, et al. Local side-effects of inhaled corticosteroids in asthmatic children: Influence of drug, dose, age, and device. Allergy. 2001;56:944–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjerkeborn K, Dahllöf G, Hedlin G, Lindell M, Modéer T. Effect of disease severity and pharmacotherapy of asthma on oral health in asthmatic children. Scand J Dent Res. 1987;95:159–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1987.tb01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnrup K, Lundin SA, Dahllöf G. Analysis of paediatric dental services provided at a regional hospital in Sweden. Dental treatment need in medically compromised children referred for dental consultation. Swed Dent J. 1993;17:255–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzoleni S, Stellini E, Cavaleri E, Angelova Volponi A, Ferro R, Fochesato Colombani S, et al. Dental caries in children with asthma undergoing treatment with short-acting beta2-agonists. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2008;9:132–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta A, Sequeira PS, Sahoo RC. Bronchial asthma and dental caries risk: Results from a case control study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2009;10:59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Houte J, Gibbons RJ, Pulkkinen AJ. Ecology of human oral lactobacilli. Infect Immun. 1972;6:723–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.5.723-729.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda T, Sandham HJ, Bradley EL., Jr Changes in Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli in plaque in relation to the initiation of dental caries in Negro children. Arch Oral Biol. 1973;18:555–66. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(73)90076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brigic A, Kobaslija S, Zukanovic A. Anti-asthmatic inhaled medications as favouring factors for increased concentration of Streptococcus mutans. Mater Sociomed. 2015;27:237–40. doi: 10.5455/msm.2015.27.237-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkatesh U. Allied health-3009. Comparative assessment of dental caries experience, oral health status, gingival health status, salivary Streptococcus mutans count and Lactobacillus count between asthmatics and non-asthmatic children aged between 5-12 years in Davangere city, Karnataka, India. World Allergy Organ J. 2013;6(Suppl 1):185. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Botelho MP, Maciel SM, Cerci Neto A, Dezan CC, Fernandes KB, de Andrade FB, et al. Cariogenic microorganisms and oral conditions in asthmatic children. Caries Res. 2011;45:386–92. doi: 10.1159/000330233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alaki SM, Ashiry EA, Bakry NS, Baghlaf KK, Bagher SM. The effects of asthma and asthma medication on dental caries and salivary characteristics in children. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2013;11:113–20. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a29366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ersin NK, Gülen F, Eronat N, Cogulu D, Demir E, Tanaç R, et al. Oral and dental manifestations of young asthmatics related to medication, severity and duration of condition. Pediatr Int. 2006;48:549–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2006.02281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karova E, Christoff G. Dental health in asthmatics treated with inhaled corticosteroids and long acting sympathicomimetics. J IMAB Ann Proc Sci Papers. 2012;18:211–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenander-Lumikari M, Laurikainen K, Kuusisto P, Vilja P. Stimulated salivary flow rate and composition in asthmatic and non-asthmatic adults. Arch Oral Biol. 1998;43:151–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(97)00110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komiyama EY, Ribeiro PM, Junqueira JC, Koga-Ito CY, Jorge AO. Prevalence of yeasts in the oral cavity of children treated with inhaled corticosteroids. Braz Oral Res. 2004;18:197–201. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242004000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samaranayake LP. Host factors and oral candidosis. In: Samaranayake LP, MacFarlane TW, editors. Oral Candidosis. UK: Butterworth and Company Ltd; 1990. pp. 66–103. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw NJ, Edmunds AT. Inhaled beclomethasone and oral candidiasis. Arch Dis Child. 1986;61:788–90. doi: 10.1136/adc.61.8.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kargul B, Tanboga I, Ergeneli S, Karakoc F, Dagli E. Inhaler medicament effects on saliva and plaque pH in asthmatic children. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1998;22:137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]