Abstract

Background:

A traumatic ulcer caused by diabetes mellitus (DM) is a lesion caused by an increase in advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs), which takes a long time to heal. AGEs cause angiogenesis, vasculogenesis and a decrease in leukocytes. Fibroblast proliferation and the number of glycosaminoglycans decline, thereby inhibiting the formation of granulation tissue, collagen deposition and platelet derivatives growth factor. The application of topical propolis extract gel to ulcers has an anti-inflammatory function, triggers angiogenesis and accelerates wound healing.

Aims:

This study sought to establish whether the topical application of propolis extract gel can increase the expression of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and fibroblasts in the healing process of traumatic ulceration in diabetic Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus).

Methods:

This was a genuinely experimental research design featuring posttest-only control groups. The simple random sampling technique involved 24 male DM Wistar rats with traumatic ulcers on the labial mucosa of the lower lip. The samples were divided into two groups: a control group whose members were administered hydroxypropyl methylcellulose gel 5% and a treatment group to which propolis extract gel was applied. The expression of FGF-2 and fibroblasts was observed on days 3, 5, 7 and 9 by means of histology and immunohistochemistry (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) with Ab-Mo FGF-2.

Results:

The topical application of propolis extract gel increased the expression of FGF-2 and fibroblasts in the treatment group on days 5 and 7. There was a correlation between the increased expression of FGF-2 and the number of fibroblasts (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

The topical application of propolis extract gel increases the expression of FGF-2 and fibroblasts within the traumatic ulcer healing process in diabetic R. norvegicus.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, fibroblast, healing process, fibroblast growth factor-2 expression, traumatic ulcer

INTRODUCTION

Wound healing in diabetes mellitus (DM) is delayed because of the interference to cell function, chronic inflammation and cytokines and growth factors (GFs). DM leads to both microvascular and macrovascular disorders that cause decreased vascularization culminating in tissue hypoxia and damage. This occurs as a result of the accumulation of advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs), which cause angiogenesis, vasculogenesis and a decrease in leukocytes. Fibroblast proliferation and a decrease in glycosaminoglycans inhibit the formation of granulation tissue, collagen deposition and platelet derivatives growth factor (PDGF) within the synthesis process of fibroblasts and collagen formation.[1,2,3] Chronic ulcers result in tissue hypoxia which delays the healing process and may cause pain when eating, swallowing and talking.[4,5]

Nowadays, many people are interested in herbal and natural therapies because of their minimal side effects or adverse impacts. Popular herbal drugs include propolis or bees wax. Propolis is a substance produced by bees and collected from the young shoots, leaves or sap of trees which is then mixed with the insects’ saliva and used to sterilize their nests. Crude propolis contains 50% resin (consisting of phenols and phenolic acid or polyphenols), 30% wax, 10% essential oils, 5% pollen and 5% various other organic compounds. Most polyphenols are flavonoids, phenolic acids and ester, phenol aldehydes, ketone and other elements.[6,7,8]

Propolis extract can be safely consumed on a daily basis as proven by toxicity tests. Such previous tests on BHK-21 fibroblast cells using Apis mellifera propolis extract confirmed that propolis is not toxic at concentrations below 3 mg/ml.[9] Moreover, a cytotoxic test of 1% propolis extract and 0.2% chlorhexidine in mouthwash revealed no toxic substances in human gingival fibroblasts.[10] Propolis with flavonoid has the effect of increasing vascularization and protection of the vascular endothelium. The results of previous clinical and experimental studies of flavonoids confirmed that they may improve vascularization and decrease instances of edema.[11] Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) in flavonoids as an antioxidant inhibits excessive oxidative reactions resulting from the inflammatory and metabolic processes following cell injury. As an anti-inflammatory, CAPE can inhibit lipoxygenase (LOX) and cyclooxygenase (COX), which are involved in metabolic pathways, as well as the release of inflammatory cytokines and increase anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-4.[12] The antioxidant effect is capable of regulating the activity of nuclear factor-κB (NF-kB) which plays a role as a regulating gene that encodes cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-1, molecular adhesin, chemokines, in addition to enzymes such as COX-2, inducible nitric oxide syntase and fibroblast growth factor (FGF).[13,14,15]

The FGF family contributes to the regulation of virtually all aspects of development and organogenesis and, following birth, to tissue maintenance, as well as particular aspects of organism physiology. FGF demonstrates the intrinsic activity of tyrosine kinases such as the proliferation and differentiation of fibroblasts. FGF is a multipotential glycoprotein that promotes the development of various cells such as dermal fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells and melanocytes. FGF plays a role in the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) for revascularization, wound healing and hematopoiesis.[1,15,16] The acceleration of wound healing was observed in the expression of FGF-2, the number of fibroblasts and capillaries. The expression of FGF-2 is a marker formation of fibroblasts.[15,16] FGF-2 as mitogenic effects are mediated through mitogenactivated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK/ERK) and phosphoinositide-3 kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) signaling pathways.[17]

Previous laboratory study was undertaken to establish the effect of topical application of propolis extract gel on diabetic mice through the expression of transformation growth factor-β (TGF-β) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9).[1] This study aimed to identify the effect of topical application of propolis extract gel that can increase the expression of FGF-2 and the number of fibroblasts in the traumatic ulceration healing process in diabetic Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study received approval and an ethical clearance letter relating to animal subjects from the Ethics Research Committee, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Universitas Airlangga Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia (T024/HRECC.FODM/II/2017). This study represented a true experimental research posttest-only control group design. The sampling technique consisted of simple random sampling involving 24 male DM Wistar rats. 50 mg/kg of streptozotocin (Sigma Aldrich®, Germany) was administered intraperitoneally and injected into Wistar rats within an animal model study of DM. Diagnosis of DM was confirmed when random blood glucose levels ≥200 mg/dl or fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dl in mice on the 3rd day after the administration of streptozotocin.

Ulcers formed 24 h after a burnisher was heated for 60 s and subsequently gently applied to the lower lip labial mucosa of the rats for a duration of 1 s. The samples were divided into two groups: a control group treated with 5% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) gel and treatment groups to which propolis extract gel was applied. For this study, a propolis extract (Lawang, East Java, Indonesia) of 1.56% concentration and cultured within a nutrient media was used.

The measured variables in this research were those of FGF and fibroblast. The expression of FGF-2 and the number of fibroblasts was observed on days 3, 5, 7 and 9. Furthermore, the mice were sacrificed and their lower lip labial mucosa tissue was taken to produce the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal preparation with hematoxilin and eosin (HE) staining (Leica Biosystems®, Singapore). Fibroblasts stained with HE appear red purple at ×400 with 10 visual fields examined by two experts. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using monoclonal antibodies (anti FGF-2 ab8880, Abcam) in an antigen reaction (FGF-2) and reacted with diaminobenzidine substrate (Sigma Aldrich®, Germany). Fibroblasts cells expressing FGF-2 appear brown at ×1000. Data were analyzed by means of ANOVA and Pearson's correlation tests. Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 17.0 software for windows 8.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

RESULTS

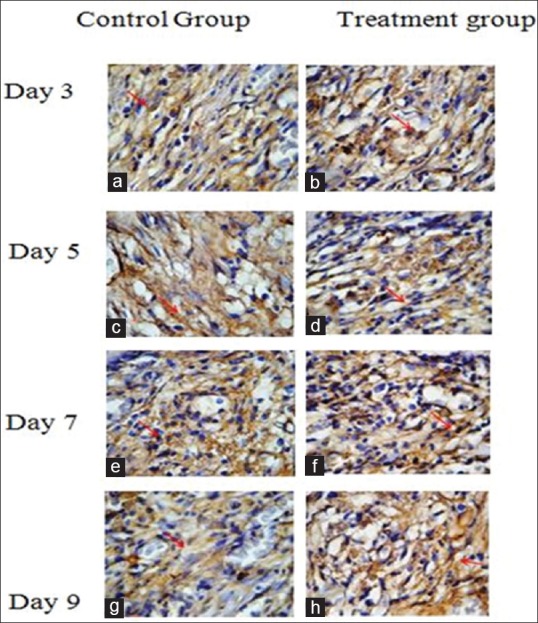

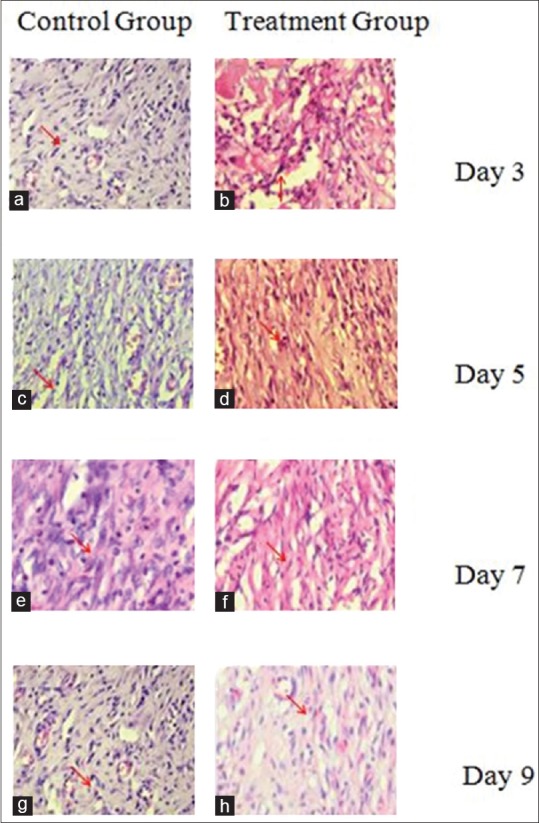

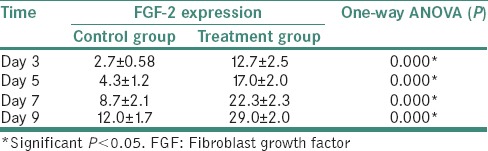

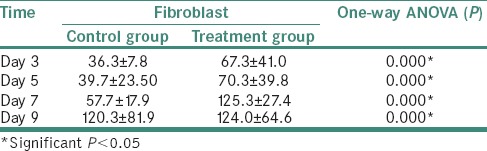

The expression of FGF-2 in the treatment group with topical application of propolis extract gel showed greater improvement than the control group [Figure 1]. The number of fibroblasts in that group increased more than that in the control group [Figure 2]. The mean result of FGF-2 expression and the number of FGF-fibroblasts with topical application of propolis extract gel and 5% HPMC are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining shows fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) expression L (×1000). A positive reaction produced a brown color in the cytoplasm due to antigen (FGF-2) with monoclonal antibodies (anti FGF-2). (a) Figure 1 also shows the expression of FGF-2 in a fibroblast control group on day 3; (b) expression of FGF-2 in the fibroblasts treatment groups on day 3; (c) expression of FGF-2 on a fibroblast control group on day 5; (d) The expression of FGF-2 in the fibroblasts treatment groups on day 5; (e) expression of FGF-2 on a fibroblast cell control group at day 7; (f) FGF-2 expression in fibroblast cell treatment groups on day 7; (g) FGF-2 expression in fibroblast cell control group on day 9; (h) expression of FGF-2 in the fibroblasts treatment groups on day 9

Figure 2.

The microscopic results of hematoxylin and eosin staining (×400) show fibroblasts which are large cells, flat, oval nuclei with smooth nuclear membranes and purplish red branches. The slides show: (a) the control group on day 3; (b).the treatment groups treated with propolis extract on day 3; (c) the control group on day 5; (d) the treatment group treated with propolis extract on day 5; (e) the control group on day 7; (f) the treatment group treated with propolis extract on day 7; (g) the control group on day 9; (h) the treatment group treated with extract of propolis on day 9

Table 1.

Mean, standard deviation and one-way ANOVA test result fibroblast growth factor-2 expression between the control and treatment groups

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation and one-way ANOVA test result fibroblast between the control and treatment groups on days 3, 5, 7 and 9

The ANOVA test results obtained indicated a significant difference (P < 0.05) in the expression of FGF-2 of each group [Table 1]. Based on the mean results, there were significantly different numbers of fibroblasts in each group (P < 0.05) [Table 2]. Pearson's test results indicated a significantly different expression of FGF-2 and the number of fibroblasts (P = 0.004 and P < 0.05, respectively). There was a positive correlation between the increased expression of FGF-2 and the number of fibroblasts.

DISCUSSION

The traumatic ulcer-healing process under normal conditions takes place approximately 24–48 h after injury. The inflammatory phase is characterized by leukocytes (polymorphonuclear [PMN]). Two days after injury, mature monocytes in connective tissue turn into macrophages and tend to increase until day 3. GFs such as TGF-β, PDGF and FGF play a role in the migration and proliferation of cells, in addition to the formation of granulated tissue. FGF plays a role in angiogenesis, pro-inflammatory cytokines and anti-inflammatory processes on days 3 and 4. The proliferation of fibroblasts occurs on the 3rd day, reach a peak on days 7–14.[1,7,14]

The FGF singling pathway is elucidated by MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt, which are known to mediate the mitogenic action of FGF. The bFGF and PDGF significantly induce both MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways in both adult and fetal fibroblasts and are attenuated by each specific receptor blocker. In addition, MEK and PI3K inhibitors intensify both cell proliferation and the percentage S-phase in both adult and fetal fibroblasts. This explains the fact that FGF is one of the most remarkable factors underlying in-cell proliferation which is directly mediated via MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways.[17]

The treatment group experiencing topical application of propolis extract gel presented a more rapid healing process than the control group. In the treatment group, ulcers began to heal with slight erythema on day 5. On day 7, white mucosal with erythema was observed and on day 9 what appeared to be normal mucosa was present. The role of flavonoids and CAPE in propolis is that of anti-inflammatory antioxidants that can enhance the proliferation of fibroblasts, re-epithelialization and accelerate the healing process.[18]

The control group on days 3 and 5 presented a yellowish ulcer, while on day 7, it appeared to have begun to shrink with the presence of necrotic tissue. On day 9, the ulcer showed evidence of healing due to the scar tissue observable. This condition indicates that DM disrupts the healing process in ulcers due to microangiopathy which causes tissue hypoxia. The inflammatory mediators (pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokine and AGEs) increase, as does the apoptosis of fibroblast and collagen formation. In addition, leukocytes, angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, proliferation and the migration of fibroblasts decreased.[13,15,16] The control groups indicated that the healing process was delayed and scar tissue formed.

The flavonoids in propolis extract can stimulate macrophages and PMN. Macrophages play a role in wound healing by releasing GFs, while also triggering angiogenesis and fibrogenesis. One type of GF is FGFs which interact with the receptors FGFR-2 on the fibroblasts’ surfaces causing dimerization and autoforilation on specific tyrosine which increases the expression of FGF-2.[19] CAPE in propolis acts as an anti-inflammatory analgesic, while also inducing macrophages. CAPE enhancing GFs inhibits MMP-9, decreases collagen degradation and increases extracellular matrix remodeling. Topical application of propolis extract can reduce inflammation due to the CAPE mechanism which inhibits NF-kB and arachidonic acid cascade.[20,21]

Propolis extracts contain bioactive material dominated by CAPE in flavonoids which are anti-inflammatory. CAPE plays a role as an anti-inflammatory that inhibits phospholipase in the arachidonic acid cascade. Therefore, it does not release prostaglandins and leukotrienes. COX is inhibited by flavonoids that suppress the stimulation and synthesis of prostaglandins and thromboxane. Flavonoids inhibit the accumulation of mast cells, whereas the main LOX is inhibited by propolis components such as quercetin which suppress the stimulation of leukotrienes and lipoxin. CAPE is lipophilic and can easily infiltrate the cell, thereby inhibiting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α) and simultaneously increasing anti-inflammatory cytokine (TGF-β, IL-10 and IL-4) and promoting fibroblast proliferation.[21,22,23]

Topical application of propolis extract gel can accelerate the wound-healing process in diabetic ulcers with direct signaling inducing FGF-2 that can enhance the proliferation of fibroblasts and accelerate the healing of ulcers.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all staff in the Department of Oral Medicine, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hozzein WN, Badr G, Al Ghamdi AA, Sayed A, Al-Waili NS, Garraud O, et al. Topical application of propolis enhances cutaneous wound healing by promoting TGF-beta/Smad-mediated collagen production in a streptozotocin-induced type I diabetic mouse model. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:940–54. doi: 10.1159/000430221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobmann R, Schultz G, Lehnert H. Proteases and the diabetic foot syndrome: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:461–71. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larjava H. Oral Wound Healing; Cell Biology and Clinical Management. West Sussex, UK: Willey Blackwell; 2012. pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Gazaerly H, Elbardisey DM, Eltokhy HM, Teaama D. Effect of transforming growth factor beta 1 on wound healing in induced diabetic rats. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2013;7:160–72. doi: 10.12816/0006040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delavarian Z, Pakfetrat A, Nazari F, Tonkaboni A, Shakeri M. Effectiveness of bee propolis on recurrent aphthous stomatitis: A randomized clinical trial. AENSI Res J Fisheries Hydrobiol. 2015;10:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dziedzic A, Kubina R, Wojtyczka RD, Kabała-Dzik A, Tanasiewicz M, Morawiec T, et al. The antibacterial effect of ethanol extract of polish propolis on mutans streptococci and lactobacilli isolated from saliva. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:681891. doi: 10.1155/2013/681891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasan AE. Healthy and Beautiful with Propolis. 7th ed. Bogor: PT Penerbit ITB Press; 2010. pp. 10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos VR. Propolis: Alternative Medicine for the Treatment of Oral Microbial Diseases. In Tech. 2010:133–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Susilo B, Mertaniasih NM, Koendhori EB, Agil M. Chemistry composition and Malang East java's propolis antimicrobial activity. J Penelit Med Eksakta. 2010;8:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yustina L. Surabaya: Tesis FKG Unair; 2013. Cytotoxicity Test of Propolis Apis mellifera L Extract on Fibroblast Cell BHK-21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozan F, Sümer Z, Polat ZA, Er K, Ozan U, Deger O, et al. Effect of mouthrinse containing propolis on oral microorganisms and human gingival fibroblasts. Eur J Dent. 2007;1:195–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarto M, Saragih H. Propolis Toxicity Test in Male Mouse (Mus Musculus L) Balb-C. Yogyakarta: Fakultas Biologi Universitas Gajah Mada; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waldner NM, Vanni R, Belibasakis GN, Thurnheer T, Attin T, Schmidlin PR. The in vitro antimicrobial efficacy of propolis against four oral pathogens: A review. Dent J. 2014;2:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araujo MA, Liberio S, Guerra R, Ribeiro MN, Nascimento FR. Mechanisms of action underlying the anti-inflamatory and immunomodulatory effects of propolis: A brief review. BJP. 2012;22:208–19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabir A. Flavonoid propolis Trigona sp antibacterial activity toward Streptococcus mutans (in vitro). Bagian Konservasi Gigi Fakultas Kedokteran Gigi Universitas Hasanudin. Surabaya Dent J. 2005;38:135–41. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akita S, Akino K, Hirano A. Basic fibroblast growth factor in scarless wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2013;2:44–9. doi: 10.1089/wound.2011.0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ornitz DM, Itoh N. The fibroblast growth factor signaling pathway. WIREs Dev Biol. 2015;4:215–23. doi: 10.1002/wdev.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmely F. Formulation of propolis gel extract from Trigona itama (Cockrell) Bee nest and its antibacterial activity towards Staphylococcus epidermidis. Prosiding Seminar Nasional dan Workshop “Perkembangan Terkini Sains Farmasi dan Klinik IV”; 2014:88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Günay A, Arpaǧ OF, Atilgan S, Yaman F, Atalay Y, Acikan I, et al. Effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on palatal mucosal defects and tooth extraction sockets. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2069–74. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S67623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miranda R. Propolis: A review of its anti-inflamatory and healing action. J Venomous Anim Toxins. 2007;13:697. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakajima Y, Tsuruma K, Shimazawa M, Mishima S, Hara H. Comparison of bee products based on assays of antioxidant capacities. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–29. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao J, Liu YC, Shi YH, Xie YQ, Cui HP, Li Y, et al. Role of rat autologous skin fibroblasts and mechanism underlying the repair of depressed scars. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:945–50. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]