Abstract

This research tested a model that integrates risk factors among non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and eating disorder (ED) behaviors with the aim of elucidating possible shared and unique mechanisms underlying both behaviors. Emotional distress, limited access to emotion regulation (ER) strategies, experiential avoidance, and NSSI/ED frequency were examined in a sample of 230 female undergraduates. Structural equation modeling indicated that limited access to ER strategies and avoidance mediated relationship between emotional distress and avoidance, which in turn was associated with NSSI and ED behaviors. Results suggest NSSI and ED behaviors may serve similar emotion regulation functions, and specifically highlight the role of experiential avoidance in these behaviors.

Keywords: eating disorders, emotion regulation, experiential avoidance, non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and disordered eating are two maladaptive behaviors that are especially common among young adults. NSSI refers to deliberate, socially unaccepted behaviors that result in tissue damage without a conscious intent to cause death (e.g., cutting, carving, burning; Claes & Vandereycken, 2007). Although the prevalence of NSSI among adult nonclinical populations has been estimated to be 4% (Briere & Gil, 1998; Klonsky, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2003), NSSI appears to be more prevalent among college populations, with rates ranging from 7% to 38% (Gollust, Eisenberg, & Golberstein, 2008; Gratz, Conrad, & Roemer, 2002; Whitlock et al., 2011). Similarly, eating disorder (ED) behaviors are common among college students (e.g., Eisenberg, Nicklett, Roeder, & Kirz, 2011; Reinking & Alexander, 2005). For example, among 6,844 female undergraduates surveyed across a 15-year period from 1990 to 2004, the point prevalence of binge eating, vomiting, laxative use, diuretic use, fasting, and excessive exercise was 7.9%, 1.8%, 1.1%, 1.6%, and 7.7%, respectively (Crowther, Armey, Luce, Dalton, & Leahey, 2008).

Evidence suggests NSSI and ED behaviors are highly comorbid and may indicate that these behaviors have similar underlying psychological processes. Among those with EDs, a previous meta-analysis found that 32.7% of those with bulimia nervosa (BN) and 27.3% of those with anorexia nervosa (AN) reported a lifetime history of NSSI (Cucchi et al., 2016), and another review found that 25.4% to 55.2% of ED patients report at least one type of NSSI; specifically, the reported occurrence of NSSI ranged from 13.6% to 42.1% among restricting-type AN samples; 27.8% to 68.1% among binge-purge AN samples; and 26.0% to 55.2% among BN samples (Svirko & Hawton, 2007). While limited data exist regarding NSSI in binge eating disorder (BED), one study found the prevalence of lifetime NSSI in BED was 19.8%, which was somewhat lower than the prevalence in BN (27.8%) and higher than the prevalence in AN (17.9%) (Claes et al., 2013). Taken together, existing studies suggest that NSSI appears to be more prevalent among EDs characterized by bulimic (i.e., binge and/or purge) behaviors (Kostro, Lerman, & Attia, 2014). Additional evidence from non-clinical samples indicates co-occurrence of disordered eating and NSSI may be especially high among college students. In an examination of NSSI behaviors among 2,843 college students, Gollust et al. (2008) found that of the female participants who reported any self-injury, the concurrent rate of probable EDs was 25.9%.

Research indicates that the co-occurrence of NSSI and ED behaviors is associated with more severe overall psychopathology, and thus may be indicative of a poor prognosis for individuals who engage in both behaviors (Claes et al., 2013; Claes, Vandereycken, & Vertommen, 2003; Muehlenkamp, Peat, Claes, & Smits, 2012). For example, NSSI/ED co-occurrence is associated with a history of trauma and abuse, depression, impulsivity, obsessive-compulsiveness, and suicidal behavior (Kostro et al., 2014). Furthermore, individuals with EDs who engage in NSSI have a greater severity of ED symptoms (Fujimori et al., 2011) and show less improvement in ED behaviors over time (Peterson & Fischer, 2012). Given the clinical implications of the comorbidity between NSSI and ED behaviors, it is important to identify emotion regulation factors that are both associated with and which may distinguish between each of these behaviors. Two models—the affect regulation model and the experiential avoidance model—are applicable to NSSI and ED psychopathology, and may serve to elucidate similar processes that drive both of these behaviors.

AFFECT REGULATION MODEL

Consistent with the affect regulation model, individuals report engaging in NSSI1 for emotional relief, distraction, escape, self-punishment, interpersonal influence, and to enhance or generate feelings or to express or release anger (Briere & Gil, 1998; Brown, Comtois, & Linehan, 2002). That is, deliberate self-harm (DSH) serves to “express, concretize, and/or control overwhelming emotions” (Chapman, Gratz, & Brown, 2006, p. 374). In support of the affect regulation function of NSSI, a review of 18 studies of NSSI behavior (Klonsky, 2007) demonstrated that negative affect precedes NSSI, NSSI is associated with intentions to alleviate negative affect, and decreased negative affect and feelings of relief tend to follow NSSI. In a later study, Klonsky (2009) found that self-injury was associated with improvements in affective valence (i.e., decreased negative affect and increased positive affect) and decreases in affective arousal among 39 individuals who reported NSSI behaviors. Specifically, these individuals reported feeling overwhelmed, sad, and frustrated prior to engaging in NSSI, and feeling relieved and calm after NSSI occurred.

The affect regulation model also has been the focus of a substantial body of research investigating the antecedents and consequences of binge eating (e.g., Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2011;). This model is based on two central tenets: first, negative affect triggers binge eating episodes, and second, binge eating functions to reduce this negative affect. Thus, via the process of negative reinforcement, binge eating becomes a habitual, learned response to the experience of negative emotions, which serves to maintain this behavior. Overall, empirical studies have yielded strong support for the affect regulation model, in that negative affect is a proximal antecedent of binge eating (Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2011), after which negative affect is reduced (e.g., Berg et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007). In addition to binge eating, evidence suggests that restriction (Haynos & Fruzzetti, 2011; Haynos et al., 2016) and purging (Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2015) serve to regulate affect, which together suggests there is broad support for affect regulation functions of a range of ED behaviors.

EXPERIENTIAL AVOIDANCE MODEL

According to the Experiential Avoidance Model (EAM), NSSI is an avoidance behavior that enables individuals to avoid unwanted emotions, thoughts, memories, and/or somatic sensations and to narrow their attention to immediate sensations (Chapman et al., 2006; Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991). Thus, through negative reinforcement, NSSI becomes an automatic escape response. In support of this theory, research has demonstrated associations between avoidance behaviors and NSSI. For instance, Gratz and Roemer (2004) found that higher levels of emotional non-acceptance were associated with self-harm behavior among male undergraduates. Similarly, thought suppression was found to be positively associated with the frequency of NSSI among a sample of 105 female inmates (Chapman, Specht, & Cellucci, 2005).

The EAM posits additional factors that contribute to experiential avoidance and NSSI, including emotional intensity, distress intolerance, and deficits in emotion regulation skills (Chapman et al., 2006). Individuals who experience greater levels of emotional intensity are more likely to avoid emotions (Lynch, Robins, Morse, & MorKrause, 2001) and engage in experiential avoidance (Sloan, 2004). Moreover, according to Chapman et al. (2006), physiological evidence (Herpertz, Kunert, Schwenger, & Sass, 1999; Herpertz et al., 2000) suggests that a low tolerance for distress, rather than objective emotional arousal, may contribute to experiential avoidance and NSSI. Perhaps most importantly, limited access to skillful emotion regulation strategies appears to be play an important role in NSSI (e.g., Gratz, 2007). Taken together, it appears that individuals who lack the ability to effectively cope with negative emotions tend to engage in experiential avoidance and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, including NSSI.

Given the substantial comorbidity between NSSI and ED behavior, it has been suggested that similar escape motivations may drive both behaviors (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991). Escape theory suggests that, like NSSI, binge eating results from cognitive narrowing (i.e., concrete, rigid thinking and a focus on immediate, proximal goals), which also functions as an escape from aversive self-awareness and negative affect (Baumeister, 1990; Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991). Research supports relationships among distress tolerance, avoidance, and ED psychopathology. For example, individuals with EDs report greater mood intolerance (Allen, McLean, & Byrne, 2012) and higher levels of avoidance of affect and more difficulties accepting and managing emotions than controls (Corstorphine, Mountford, Tomlinson, Waller, & Meyer, 2007).

CO-OCCURRING ED AND NSSI

In sum, it appears that the aforementioned models of NSSI and ED behaviors highlight the role of similar emotion regulation deficits (e.g., Chapman et al., 2006; Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2011; Klonsky, 2009; Nock & Prinstein, 2004, 2005). Furthermore, a growing body of literature examining co-occurring NSSI and ED behaviors suggests similar mechanisms may maintain these behaviors. For instance, Claes, Klonsky, Muehlenkamp, Kuppens, and Vandereycken (2010) found that the avoidance or suppression of negative feelings was the most common reason patients with EDs reported engaging in many types of NSSI. In addition, before to after NSSI behavior, positive-low-arousal (e.g., relief) affect increased, whereas negative-high-arousal (e.g., anger, anxiety) affect decreased Claes et al. (2010). In a study of NSSI among 376 female ED inpatients, 69.2% of those who reported ever having engaged in NSSI behavior reported feeling better immediately after engaging in NSSI behaviors (Paul, Schroeter, Dahme, & Nutzinger, 2002). Similarly, Muehlenkamp et al. (2009) used ecological momentary assessment to assess affective change in a subset of individuals with BN who also reported NSSI behaviors. Results indicated negative affect increased and positive affect decreased prior to NSSI behavior, and positive affect increased after NSSI. Taken together, these patterns of affective changes are similar to the affective antecedents and consequences of binge episodes (Berg et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007), which suggests that both binge eating and NSSI behaviors serve similar emotion regulation functions.

Despite the aforementioned findings regarding the similarity in the psychological mechanisms underlying NSSI and EDs, to date, only one study has tested a conceptual model that may account for the comorbidity between these behaviors. Using a sample of 422 adult females at an inpatient ED unit, Muehlenkamp, Claes, Smits, Peat, and Vandereycken (2011) evaluated a model that posited NSSI results from childhood traumatic experiences, low self-esteem, psychopathology, dissociation, and body dissatisfaction. This model accounted for 15% of the variance in NSSI, which was predicted by two indirect paths. The first path led from childhood abuse and low self-esteem to psychopathology, which then led to dissociation, and finally, to NSSI; the second path led from childhood abuse to low self-esteem, which then led to body dissatisfaction, and, finally, to NSSI. Notably, dissociation and body dissatisfaction were the most proximal predictors of NSSI, suggesting these factors are particularly influential in NSSI.

Based on the existing literature, Claes and Muehlenkamp (2014) developed a conceptual model that describes distal (i.e., temperament, personality, family environment, traumatic experiences, cultural pressures) and proximal (i.e., emotion regulation, cognitive distortions, low body regard, dissociation, peer influence, psychiatric comorbidity) risk factors, which Claes and Muehlenkamp (2014) argue interact with stressful life events to increase an individual’s vulnerability to developing NSSI, ED psychopathology, and/or both behaviors. Such risk factors have shown similar associations with ED psychopathology and NSSI and may be particularly influential in the co-occurrence of these behaviors (Claes & Muehlenkamp, 2014). For instance, in regards to distal temperamental risk factors, both NSSI and ED psychopathology are related to sensitivity to negative emotions, difficulties tolerating negative emotions, and increased efforts to control negative emotions (Chapman et al., 2006; Ghaderi & Berit, 2000; Najmi, Wegner, & Nock, 2007; Nock & Mendes, 2008), which is consistent with the EAM of NSSI and ED psychopathology (Corstorphine et al., 2007; Kingston, Clark, & Remington, 2010).

This model also identifies emotion regulation, specifically distress intolerance, as a proximal risk factor that appears to play an important role in the development and/or maintenance of these behaviors, as they serve to modulate the intensity of negative emotions (Claes & Muehlenkamp, 2014). Furthermore, engaging in experiential avoidance may depend on both the degree of an individuals’ distress intolerance and the absence of emotion regulation skills for decreasing distress (McHugh, Reynolds, Leyro, & Otto, 2013). McHugh et al. (2013) examined the relative contributions of distress intolerance and emotion regulation skill repertoire to experiential avoidance in clinical (i.e., outpatients with anxiety and/or mood disorders) and non-clinical samples. In both samples, distress intolerance and limited access to emotion regulation strategies were associated with higher levels of experiential avoidance, and this effect was additive rather than interactive. Such findings suggest that distress intolerance and access to emotion regulation strategies are distinct constructs that may contribute to avoidance and maladaptive behaviors (i.e., ED psychopathology and NSSI), which is consistent with the model proposed by Claes and Muehlenkamp (2014).

While the findings of the previous model evaluated by Muehlenkamp et al. (2011) are informative, this study examined factors associated with NSSI in a sample of individuals previously diagnosed with EDs, and it is important to elucidate factors associated with these behaviors within a nonclinical sample, especially among young adult populations who are at particularly high risk for these maladaptive behaviors (Gollust et al., 2008). The results of such an investigation will have significant implications for intervention and prevention. Identifying such processes would be informative to the development of intervention and prevention efforts that target these processes. To this end, it would be desirable to draw upon existing theoretical frameworks that have explicated underlying processes of these behaviors (i.e., affect regulation and experiential avoidance models).

THE PRESENT STUDY

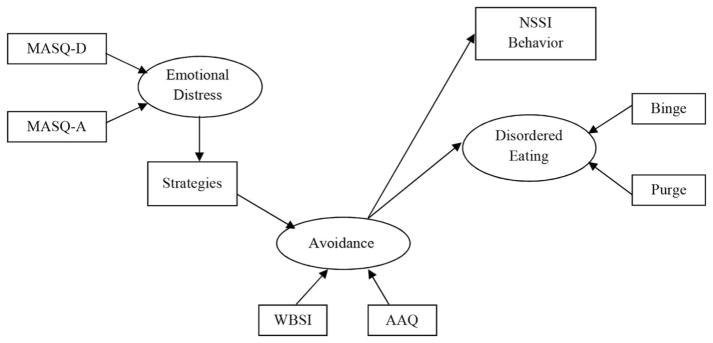

Consistent with the conceptual model proposed by Claes and Muehlenkamp (2014), the present study sought to empirically assess a model that integrates possible shared risk factors and unique mechanisms of influence. Drawing from the affect regulation and experiential avoidance models, we attempted to elucidate the association between emotional distress, emotion regulation, avoidance, NSSI, and ED psychopathology. While these variables have been broadly implicated in both NSSI and EDs, it is also possible that the specific paths of influence between these risk factors and ED and NSSI behaviors may differ. Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized model. ED behaviors were operationalized as the frequency of binge eating episodes and compensatory behaviors (i.e., self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse, fasting, and excessive exercise), which is also consistent with literature suggesting that NSSI is most relevant to binge and purge behaviors (Kostro et al., 2014). NSSI was operationalized as the deliberate, direct destruction or alteration of body tissue without conscious suicidal intent (Favazza, 1998; Pattison & Kahan, 1983).

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized relationships between emotional distress, avoidance, Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI), and disordered eating. MASQQ-D=Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire-Short Form (MASQ) General Distress Depressive Symptoms subscale; MASQ-A = MASQ General Distress Anxious Symptoms subscale; Strategies = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies subscale; WBSI = White Bear Suppression Inventory; AAQ = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; NSSI Behavior = NSSI as measured by the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; Binge = Frequency of binge episodes as measured by the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale; Purge = Frequency of purging episodes as measured by the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale.

We hypothesized positive relationships between emotional distress and limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, between limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies and cognitive and affective avoidance of aversive emotional experiences, and between cognitive and affective avoidance and maladaptive behaviors, manifested in the form of NSSI and/or ED behaviors (i.e., binge eating and compensatory behaviors). Previous literature (i.e., Schramm, Venta, & Sharp, 2013) found that experiential avoidance partially mediated the relationship between emotion regulation and other forms of psychopathology (i.e., borderline personality features). Given these findings, it was hypothesized that the relationship between distress and avoidance would be explained (i.e., mediated) by a lack of effective emotion regulation strategies, and the relationship between limited access to emotion regulation strategies and ED behaviors and NSSI would be explained by avoidance of aversive emotion.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 230 female undergraduates (Age: M = 18.76 years, SD = 2.99) who volunteered to participate in a larger study on student thoughts and behaviors. Participants were predominantly Caucasian (n = 194, 84.3%), with smaller percentages of individuals identifying as African American (n = 19, 8.3%), multiethnic (n = 6, 2.6%), Latino American (n = 3, 1.3%), Asian American (n = 2, 0.9%), and other ethnicities (n = 6, 2.6%).

Measures

The Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire-Short Form (MASQ-SF; Watson & Clark, 1991) is a 62-item self-report questionnaire that assesses depressive and anxious symptomatology. Respondents indicate how often they have experienced each symptom on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely). The MASQ-SF contains four subscales: an 11-item General Distress Anxious Symptoms subscale (MASQ-A), measuring anxious mood; a 12-item General Distress Depressive Symptoms subscale (MASQ-D), measuring depressed mood; a 17-item Anxious Arousal subscale, measuring hyper-arousal and bodily tension; and a 22-item Anhedonic Depression subscale, measuring loss of pleasure, disinterest, and low energy. Higher scores suggest greater levels of symptoms. The MASQ has demonstrated good internal consistency as well as good convergent and discriminant validity (Watson et al., 1995). For this study, the two general distress scales were used as proxies for participant emotional distress. For this sample, the MASQ-D and MASQ-A had excellent internal consistency (MASQ-D: α = .94; MASQ-A: α = .90).

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item self-report questionnaire that measures emotion regulation in respondents. The DERS has six subscales: Nonacceptance of emotional responses, Difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, Impulse control difficulties, Lack of emotional awareness, Limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and Lack of emotional clarity. Participants are asked to indicate how often each item occurs along a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = almost never (0–10%); 5 = almost always (91–100%)). The DERS subscales have shown good internal consistency (all α ‘s > .80) and adequate test-retest reliability (p’s ranging from .57 to .80), and the DERS has good convergent and discriminant validity in college students (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). In the present study, the Limited access to emotion regulation strategies subscale was used, as this subscale has demonstrated associations with both NSSI (Perez, Venta, Garnaat, & Sharp, 2012) and ED psychopathology (Whiteside, Chen, Neighbors, Hunter, Lo, & Larimer, 2007). For this sample, this subscale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .91).

The White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI; Wegner & Zanakos, 1994) is a 15-item self-report measure that is used to evaluate the tendency to suppress unwanted or negative thoughts. Participants respond to each item using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree; 5 = Strongly agree). Higher scores on the WBSI suggest a stronger likelihood that the respondent attempts to suppress or avoid their unwanted thoughts. The WBSI has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .89) and test-retest reliability over a 12-week period (r = .80) (Muris, Merckelbach, & Horselenberg, 1996). In the present study, the WBSI was conceptualized as a measure of cognitive avoidance. For this sample, the WBSI had excellent internal consistency (α = .92).

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ; Hayes et al., 2004) is a 16-item self-report questionnaire that assesses a respondent’s level of experiential avoidance. Participants respond to items using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Never true; 7 = Always true). Higher scores on this measure indicate higher levels of experiential avoidance, and possible scores range from 9 to 112. The AAQ has adequate internal consistency (α = .70) and test-retest reliability (r = .64 for the 16-item version of the AAQ). In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .65. An internal consistency of this magnitude is not that uncommon for the AAQ. Since the inception of this measure, previous studies have found alpha levels in this range (c.f., Bond et al., 2011). Others have suggested that this low internal consistency is normative, as it indicates that experiential avoidance is “not seen as representing a stable, internally consistent underlying trait” (Boelen & Reijntjes, 2008, p. 249).

The Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz, 2001) is a 17-item self-report measure that evaluates the age of onset, frequency, severity, duration, and type of self-harm in the absence of suicidal intent. For the first 16 classified NSSI behaviors, respondents indicate whether they have “ever intentionally (i.e., on purpose)” engaged in a particular NSSI behavior. The final item is open-ended and queries if the individual has engaged in any other NSSI behavior that was not included on the questionnaire. In the present study, NSSI frequency was used as the outcome. Gratz (2001) suggested that the DSHI has good internal consistency (α = .82) and test-retest reliability over a 2–4 week period (r = .68). The DSHI also tends to correlate more highly with conceptually similar measures (e.g., other measures of NSSI and borderline personality disorder) than those that are less conceptually relevant (suicide attempts, age, history of therapy) to NSSI. In the present study, the internal consistency of the DSHI was excellent (α = .92).

The Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS; Stice, Telch, & Rizvi, 2000) is a 22-item self-report inventory that assesses DSM-IV criteria for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Further, items on the EDDS can be summed to create a symptom composite score. Previous research has indicated that the overall symptom composite had good internal consistency (α = .89) and test re-test reliability (r = .87). For the current study, only items related to binging and purging were used as measures of ED behavior. Specifically, EDDS items 15, 16, 17, and 18 were summed to create a compensatory strategies subscale that assesses the frequency of compensatory behavior (i.e., self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse, fasting, and excessive exercise) over the last 3 months, while EDDS item 8 was used to assess the frequency of binge episodes. The internal consistency of the Purge subscale was .72.

Procedure

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Kent State University. Participants volunteered to participate in a larger study of repetitive thoughts and behaviors through an online software system. Following informed consent, participants met in small groups of up to 10 individuals to complete a packet of self-report questionnaires that took approximately 45 minutes to 1 hour to complete. All volunteers received credit toward the research requirement in their psychology course for participating in this study.

RESULTS

Preliminary Screening

Examination of the dataset revealed that 0.16% of all data were missing. Missing data were handled through full information maximum likelihood estimation (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Because this was a college sample, NSSI, binge eating, and purging were not normally distributed. Square-root transformations were applied to these behavioral variables, which resulted in variables that were sufficiently normally distributed. All remaining variables met criteria for univariate normality (Curran, West, & Finch, 1996). There was no indication the data did not meet the assumption of multivariate normality. Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations between all measures.

TABLE 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations Between Measured Variables (N=230)

| Variables | M | SD | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MASQ-D | 25.73 | 9.79 | .71** | .65** | .51** | .50** | .27** | .25** | .24** |

| 2. MASQ-A | 21.52 | 6.75 | — | .54** | .46** | .42** | .23** | .25** | .22** |

| 3. Strategies | 16.05 | 7.18 | — | .53** | .61** | .28** | .23** | .39** | |

| 4. WBSI | 45.99 | 13.21 | — | .42** | .24** | .23** | .25** | ||

| 5. AAQ | 55.39 | 10.54 | — | .24** | .17** | .18** | |||

| 6. Binge | 1.24 | 2.13 | — | .38** | .10 | ||||

| 7. Purge | 3.52 | 6.36 | — | .12 | |||||

| 8. DSHI | 0.55 | 1.29 | — |

Note. MASQ-D: Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire-Short Form-General Distress Depressive Symptoms; MASQ-A: Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire-Short Form-General Distress Anxious Symptoms; Strategies: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Limited access to emotion regulation strategies; WBSI: White Bear Suppression Inventory; AAQ: Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; Binge: sum of Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale items 7 and 8; Purge: sum of Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale 15–18; DSHI: Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory.

p<.05;

p<.01.

Structural Equation Modeling

Figure 1 displays the hypothesized model. In order to test the proposed model, structural equation modeling was conducted using Mplus 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). First, the measurement model was evaluated, followed by the evaluation of the structural model. Parameters were estimated using Maximum Likelihood methods. Following the recommendations of Hsu and Bentler (1999), several fit indices were used to evaluate model fit, including the Chi-Square statistic, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square for comparing nested models. Good model fit is indicated by a non-significant Chi-Square value, values greater than .95 for the CFI, values less than .05 for the RMSEA, and values less than .06 for SRMR (Hsu & Bentler, 1999).

Model Estimation

The initial measurement model was a good fit with the observed data, χ2(12) = 5.97, p = .92, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, SRMR = .01. In evaluating the model depicted in Figure 1, results suggested that the hypothesized model could be improved, χ2(17) = 33.97, p = .000, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .05. Model respecification indices suggested the addition of another path from emotional distress to avoidance (M.I. = 20.27), which was theoretically consistent with our hypotheses (e.g., Claes & Muehlenkamp, 2014; McHugh et al. 2013).

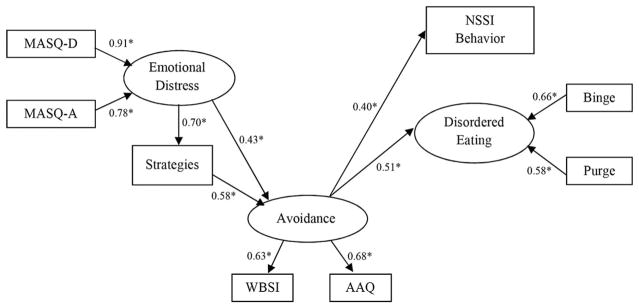

Following this modification, the fit indices of the revised model evidenced improvement: χ2(16) = 12.03, p = .74, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA =.00 (CI90% = .00–.05), SRMR =.02. Furthermore, a Chi-square difference test confirmed that the revised model was a significant improvement in model fit, as evidenced by a significant Chi-square difference value: , p < .001. Figure 2 displays the standardized parameter estimates and significance levels of pathways in the revised model. This model accounted for 16% of the variance in NSSI and 26% of the variance in ED behavior. Emotional distress had direct and positive associations with limited access to emotion regulation strategies and avoidance. That is, higher levels of emotional distress were related to more limited access to emotion regulation strategies and greater cognitive and affective avoidance. Additionally, avoidance had direct and positive associations with NSSI and ED behaviors, suggesting that greater cognitive and affective avoidance was related to more frequent NSSI and ED behaviors.

FIGURE 2.

Revised model with standardized parameter estimates and significance levels (*p<.05).

Tests of indirect effects revealed two indirect pathways from emotional distress to disordered eating and two indirect pathways from emotional distress to NSSI. Emotional distress was associated with disordered eating sequentially via limited access to emotion regulation strategies and avoidance (standardized estimate = .21, p < .001) and via avoidance only (standardized estimate = .22, p < .001). Emotional distress was associated with NSSI sequentially via limited access to emotion regulation strategies and avoidance (standardized estimate = .16, p < .001) and via avoidance only (standardized estimate = .17, p < .001).

DISCUSSION

Informed by the distal and proximal risk factors in the model proposed by Claes and Muehlenkamp (2014), this research examined an integrated model of the associations among emotional distress, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, avoidance, and two behavioral outcomes: NSSI and ED behaviors (specifically binge eating and compensatory behaviors). A revised model, which added a pathway between emotional distress and avoidance, provided an excellent fit to the data. In support of our hypotheses, we found that the relationship between emotional distress and avoidance was mediated by limited access to emotion regulation strategies. Thus, these data suggest that distressed individuals who draw from a limited range of effective emotion regulation strategies report greater cognitive and emotional avoidance, which is consistent with previous findings that individuals who have fewer emotion regulation strategies to draw from are also more likely to engage in avoidance (e.g., Boulanger, Hayes, & Pistorello, 2010; McHugh et al., 2013). Furthermore, our findings are generally consistent with literature that suggests thought suppression may partially mediate the relationship between negative affect and ED symptoms (e.g., Lavender, Anderson, & Gratz, 2012; Soetens, Braet, & Moens, 2008).

Consistent with the Experiential Avoidance Model, our results indicated a significant but moderate association between avoidance and NSSI, suggesting that the desire to escape from unwanted thoughts and emotions may drive NSSI. Avoidance also was strongly and significantly associated with disordered eating, thus highlighting the potential role of avoidance in disordered eating behaviors. Additionally, emotional distress was indirectly associated with ED behaviors and NSSI. Thus, consistent with the affect regulation and experiential avoidance models, it may be that avoidance is one mechanism by which the relationship between negative emotions and these maladaptive behaviors is maintained.

Limitations

We note that the use of a female undergraduate sample may limit the generalizability of our results. However, since female college students fall within the critical age range during which both of these behaviors occur, the findings remain important to understanding NSSI and ED psychopathology. Additionally, the specific use of college students limits our understanding to only understanding these processes to non-clinical samples. These findings also are limited by their cross-sectional nature. Whereas it is important to understand potential mechanisms in the study of NSSI and ED psychopathology, the findings of the current study are tentative until prospective research is conducted. We also emphasize that the use of self-report also limits our results, as there is bias that comes with this type of reporting that is reduced with other types of reporting (e.g., interviews, independent raters). A final limitation of this study is the limited number of affect regulation variables. It is important to understand that there may be other emotion regulation/regulation variables that are associated with NSSI and disordered eating but were not measured in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite such limitations, the present results are consistent with previous research findings that these two behaviors are functionally related based on their relationship to emotion regulation difficulties (e.g., Muehlenkamp et al., 2012; Safer, Lively, Telch, & Agras, 2009; Solano, Fernández-Aranda, Aitken, López, & Vallejo, 2005). However, there may be other intervening variables worthy of investigation in future research. For instance, individual differences in impulsivity may be an important construct to assess in future studies, as evidence suggests that impulsivity is strongly associated with both ED and NSSI behaviors (e.g., Claes et al., 2013; Fawcett, 2001; Peterson & Fischer, 2012; Skegg, 2005). Furthermore, individuals who engage in both disordered eating and NSSI are significantly more impulsive than those who only engage in disordered eating (Claes et al., 2013). Thus, it may be that due to this impulsivity, individuals who engage in NSSI do not attempt to engage in any emotion regulation strategy (other than avoidance) prior to engaging in NSSI. Additionally, future studies may investigate other emotion regulation variables related to NSSI, such as distress tolerance. That is, the degree to which distressed individuals can tolerate highly affect-laden emotions and regulate their impulses is likely to help explain why some individuals engage in one of these outcome variables over the other (Nock & Mendes, 2008; Raykos, Byrne, & Watson, 2009).

Furthermore, future prospective studies should explore the differential relationships between body image concerns and depression among individuals engaging in disordered eating and/or NSSI. Recent evidence has suggested that individuals who engage in disordered eating behavior (as opposed to both disordered eating and NSSI) report higher levels of investment in the body and greater body dissatisfaction compared to those who only engage in NSSI, and this dissimilarity reliably differentiates these two groups (Muehlenkamp et al., 2012). The same study also found that higher levels of depression differentiated between individuals who engage in NSSI from those who engage in disordered eating. Taken together, it will be necessary for future longitudinal studies of EDs and NSSI to simultaneously examine trait impulsivity, multiple facets of emotion regulation (e.g., distress tolerance), body image concerns, and depression in order to fully elucidate etiological mechanisms and the risk for comorbidity between these behaviors.

The results of the present study suggest that avoidance plays a critical role in NSSI and disordered eating. Thus, in line with the model of Claes and Muehlenkamp (2014), it appears that there are shared factors associated with disordered eating and NSSI behaviors. Our findings suggest that treatments focused on decreasing emotion regulation and/or avoidance are likely to result in reduction of disordered eating and NSSI behaviors. Third-wave treatments such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Rowland, 2012; Sandoz, Wilson, & DuFrene, 2011), Dialectical Behavior Therapy, and Mindfulness-based approaches (Safer, Telch, & Chen, 2009; Stanley, Brodsky, Nelson, & Dulit, 2007), which target avoidance and emotion regulation, may be particularly effective in treatment of NSSI and EDs. This is supported by two recent small-scale therapy studies aimed at reducing both types of behaviors (Federici & Wisniewski, 2013; Fischer & Peterson, 2015). That is, for individuals with co-occurring NSSI and ED, it appears that a more focused emphasis on acceptance and emotion regulation skills could maximize therapeutic gains by targeting the shared mechanisms indicated in the present study. However, further research is necessary to assess efficacy of these treatments for co-occurring NSSI and EDs. And although the initial results of these small trials are promising, they underscore the need for continued efforts to understand and address the shared and unique factors associated with NSSI and EDs. Nevertheless, the present study builds upon and integrates existing theoretical conceptualizations of common mechanisms underlying NSSI and EDs.

Footnotes

In this introduction, NSSI will be used synonymously with Deliberate Self-Harm (DSH).

References

- Allen KL, McLean NJ, Byrne SM. Evaluation of a new measure of mood intolerance, the Tolerance of Mood States scale (TOMS): Psychometric properties and associations with eating disorder symptoms. Eating Behaviors. 2012;13(4):326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF. Suicide as escape from self. Psychological Review. 1990;97(1):90–113. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.97.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Crosby RD, Cao L, Peterson CB, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Wonderlich SA. Facets of negative affect prior to and following binge-only, purge-only, and binge/purge events in women with bulimia nervosa. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(1):111. doi: 10.1037/a0029703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, Reijntjes A. Measuring experiential avoidance: Reliability and validity of the Dutch 9-item acceptance and action questionnaire (AAQ) Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2008;30(4):241–251. doi: 10.1007/s10862-008-9082-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, … Zettle RD. Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42(4):676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger JL, Hayes SC, Pistorello J. Experiential avoidance as a functional contextual concept. In: Kring AM, Sloan DM, editors. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: Prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(4):609–620. doi: 10.1037/h0080369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MZ, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(1):198–202. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(3):371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Specht MW, Cellucci T. Borderline personality disorder and deliberate self-harm: Does experiential avoidance play a role? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35(4):388–399. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.4.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes L, Fernandez-Aranda F, Jimenez-Murcia S, Botella C, Casanueva FF, de la Torre R, … Menchón JM. Co-occurrence of non-suicidal self-injury and impulsivity in extreme weight conditions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;54:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claes L, Klonsky ED, Muehlenkamp J, Kuppens P, Vandereycken W. The affect-regulation function of nonsuicidal self-injury in eating-disordered patients: Which affect states are regulated? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes L, Muehlenkamp JL, editors. Non-suicidal self-injury in eating disorders. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Claes L, Vandereycken W. Self-injurious behavior: Differential diagnosis and functional differentiation. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes L, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H. Eating-disordered patients with and without self-injurious behaviours: A comparison of psychopathological features. European Eating Disorders Review. 2003;11(5):379–396. doi: 10.1002/erv.510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corstorphine E, Mountford V, Tomlinson S, Waller G, Meyer C. Distress tolerance in the eating disorders. Eating Behaviors. 2007;8(1):91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther JH, Armey M, Luce KH, Dalton GR, Leahey T. The point prevalence of bulimic disorders from 1990 to 2004. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(6):491–497. doi: 10.1002/eat.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucchi A, Ryan D, Konstantakopoulos G, Stroumpa S, Kaçar AŞ, Renshaw S, … Kravariti E. Lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46(7):1345–1358. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1996;1(1):16. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Nicklett EJ, Roeder K, Kirz NE. Eating disorder symptoms among college students: Prevalence, persistence, correlates, and treatment-seeking. Journal of American College Health. 2011;59(8):700–707. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.546461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem0803_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favazza AR. The coming of age of self-mutilation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186(5):259–268. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199805000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J. Treating impulsivity and anxiety in the suicidal patient. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;932:94–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federici A, Wisniewski L. An intensive DBT program for patients with multidiagnostic eating disorder presentations: A case series analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;46(4):322–331. doi: 10.1002/eat.22112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Peterson C. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescent binge eating, purging, suicidal behavior, and non-suicidal self-injury: A pilot study. Psychotherapy. 2015;52(1):78. doi: 10.1037/a0036065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori A, Wada Y, Yamashita T, Choi H, Nishizawa S, Yamamoto H, Fukui K. Parental bonding in patients with eating disorders and selfYinjurious behavior. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2011;65(3):272–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi A, Berit S. Coping in dieting and eating disorders: A population-based study. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2000;188:273–279. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust S, Eisenberg D, Golberstein E. Prevalence and correlates of self-injury among university students. Journal of American College Health. 2008;56:491–498. doi: 10.3200/jach.56.5.491-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL. Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23(4):253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL. Targeting emotion dysregulation in the treatment of selfYinjury. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63(11):1091–1103. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Conrad SD, Roemer L. Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72(1):128–140. doi: 10.1037//0002-9432.72.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and regulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26(1):41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Haedt-Matt A, Keel PK. Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(4):660–681. doi: 10.1037/a0023660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK. Affect regulation and purging: An ecological momentary assessment study in purging disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;124(2):399. doi: 10.1037/a0038815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynos AF, Fruzzetti AE. Anorexia nervosa as a disorder of emotion dysregulation: Evidence and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18(3):183–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01250.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG, Bissett RT, Pistorello J, Toarmino D, … McCurry SM. Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record. 2004;54(4):553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Haynos AF, Berg KC, Cao L, Crosby RD, Lavender JM, Utzinger LM, … Peterson CB. Trajectories of higher-and lower-order dimensions of negative and positive affect relative to restrictive eating in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1037/abn0000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(1):86–108. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpertz SC, Kunert HJ, Schwenger UB, Sass H. Affective responsiveness in borderline personality disorder: A psychophysiological approach. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1550–1556. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpertz SC, Schwenger UB, Kunert HJ, Lukas G, Gretzer U, Nutzmann J, … Sass H. Emotional responses in patients with borderline as compared with avoidant personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14(4):339–351. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L, Bentler M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston J, Clark S, Remington B. Experiential avoidance and problem behavior: A mediational analysis. Behavior Modification. 2010;34:145–163. doi: 10.1177/0145445510362575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27(2):226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of self-injury in young adults who cut themselves: Clarifying the evidence for affect-regulation. Psychiatry Research. 2009;166(2–3):260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1501–1508. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostro K, Lerman JB, Attia E. The current status of suicide and self-injury in eating disorders: a narrative review. Journal of Eating Disorders. 2014;2(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40337-014-0019-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, Anderson DA, Gratz KL. Examining the association between thought suppression and eating disorder symptoms in men. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36(6):788–795. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9403-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TR, Robins CJ, Morse JQ, MorKrause ED. A mediational model relating affect intensity, emotion inhibition, and psychological distress. Behavior Therapy. 2001;32(3):519–536. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(01)80034-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Reynolds EK, Leyro TM, Otto MW. An examination of the association of distress intolerance and emotion regulation with avoidance. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2013;37(2):363–367. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9463-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Smits D, Peat CM, Vandereycken W. Non-suicidal self-injury in eating disordered patients: A test of a conceptual model. Psychiatry Research. 2011;188(1):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Engel SG, Wadeson A, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Simonich H, Mitchell JE. Emotional states preceding and following acts of non-suicidal self-injury in bulimia nervosa patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(1):83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Peat C, Claes L, Smits D. Self-injury and disordered eating: Expressing emotion regulation through the body. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2012;42:416–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.2012.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Horselenberg R. Individual differences in thought suppression. The White Bear Suppression inventory: Factor structure, reliability, validity and correlates. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34(5–6):501–513. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Najmi S, Wegner DM, Nock MK. Thought suppression and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2007;45:1957–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Mendes WB. Physiological arousal, distress tolerance, and social problem solving deficits among adolescent self-injurers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:28–38. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.76.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(1):140–146. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.114.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattison EM, Kahan J. The deliberate self-harm syndrome. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140(7):867–872. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.7.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul T, Schroeter K, Dahme B, Nutzinger DO. Self-injurious behavior in women with eating disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):408–411. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez J, Venta A, Garnaat S, Sharp C. The difficulties in emotion regulation scale: Factor structure and association with nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent inpatients. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2012;34(3):393–404. doi: 10.1007/s10862-012-9292-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CM, Fischer S. A prospective study of the influence of the UPPS model of impulsivity on the co-occurrence of bulimic symptoms and non-suicidal self-injury. Eating Behaviors. 2012;13(4):335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raykos BC, Byrne SM, Watson H. Confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis of the distress tolerance scale (DTS) in a clinical sample of eating disorder patients. Eating Behaviors. 2009;10(4):215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinking MF, Alexander LE. Prevalence of disordered-eating behaviors in undergraduate female collegiate athletes and nonathletes. Journal of Athletic Training. 2005;40(1):47–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland M. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. 2012. Acceptance and commitment therapy for non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Safer DL, Lively TJ, Telch CF, Agras WS. Predictors of relapse following successful dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;32(2):155–163. doi: 10.1002/eat.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safer DL, Telch CF, Chen EY. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoz EK, Wilson KG, DuFrene T. Acceptance and commitment therapy for eating disorders: A process-focused guide to treating anorexia and bulimia. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm AT, Venta A, Sharp C. The role of experiential avoidance in the association between borderline features and emotion regulation in adolescents. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2013;4(2):138–144. doi: 10.1037/a0031389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skegg K. Self-harm. The Lancet. 2005;366(9495):1471–1483. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67600-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM. Emotion regulation in action: Emotional reactivity in experiential avoidance. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42(11):1257–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(4):629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soetens B, Braet C, Moens E. Thought suppression in obese and non-obese restrained eaters: Piece of cake or forbidden fruit? European Eating Disorders Review. 2008;16(1):67–76. doi: 10.1002/erv.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R, Fernández-Aranda F, Aitken A, López C, Vallejo J. Self-injurious behaviour in people with eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review. 2005;13(1):3–10. doi: 10.1002/erv.618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Brodsky B, Nelson JD, Dulit R. Brief dialectical behavior therapy (DBT-B) for suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self injury. Archives of Suicide Research. 2007;11(4):337–341. doi: 10.1080/13811110701542069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Telch CF, Rizvi SL. Development and validation of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: A brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12(2):123–131. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svirko E, Hawton K. Self-injurious behavior and eating disorders: The extent and nature of the association. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007;37(4):409–421. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. Unpublished manuscript. Iowa City: University of Iowa, Department of Psychology; 1991. The mood and anxiety symptom questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: II. Exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104(1):15–25. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.104.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner DM, Zanakos S. Chronic thought suppression. Journal of Personality. 1994;62(4):615–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside U, Chen E, Neighbors C, Hunter D, Lo T, Larimer M. Difficulties regulating emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect? Eating Behaviors. 2007;8(2):162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Purington A, Eckenrode J, Barreira P, Baral Abrams G, … Knox K. Nonsuicidal self-injury in a college population: General trends and sex differences. Journal of American College Health. 2011;59(8):691–698. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.529626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]