Abstract

Objective

In different-sex couples, individual and partner stress can both have a negative impact on relationship functioning (actor and partner effects). Gay and bisexual men experience unique stress (sexual minority stress), but few studies have examined the effects of this stress on relationship functioning among young male couples. The current study examined: (1) actor and partner effects of general and minority stress (internalized stigma, microaggressions, victimization, and outness) on relationship functioning (relationship quality and negative relationship interactions); (2) interactions between individual and partner stress as predictors of relationship functioning; and (3) dyadic coping and relationship length as moderators of actor and partner effects.

Method

Actor-partner interdependence models were tested using data from 153 young male couples.

Results

There was strong support for actor effects. Higher general stress and internalized stigma were associated with lower relationship quality, but only for those in longer relationships. Additionally, higher general stress, internalized stigma, and microaggressions, and lower outness, were associated with more negative relationship interactions. There was limited support for partner effects. Having a partner with higher internalized stigma was associated with more negative relationship interactions, but none of the other partner effects were significant. There was no support for individual and partner stress interacting to predict relationship functioning or for dyadic coping as a stress buffer.

Conclusions

Findings highlight the influence of one’s own experiences of general and minority stress on relationship functioning, but raise questions about how partner stress influences relationship functioning among young male couples.

Keywords: same-sex couples, relationships, gay/bisexual, dyadic, minority stress

Research on different-sex couples has demonstrated that individual and partner experiences of stress can both have a negative impact on relationship functioning (Bodenmann, 2005; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009; Story & Bradbury, 2004). Sexual minorities experience unique stress related to their sexual orientation and relationships (Meyer, 2003), but there has been limited attention to stress and relationship functioning among same-sex couples, especially during adolescence and early adulthood when relationship experiences can have enduring effects into later adulthood (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009). Therefore, it remains unclear if individual and partner experiences of general and minority stress have a negative impact on same-sex relationship functioning during these periods. Disentangling the effects of individual and partner experiences of stress on relationship functioning among young same-sex couples can inform interventions to improve individual and relationship functioning throughout development.

Several relationship theories propose that stress experienced by either partner in a couple can have a negative impact on relationship functioning (Randall & Bodenmann, 2009; Story & Bradbury, 2004). In addition to one’s own experience of stress contributing to negative relationship outcomes (e.g., dissatisfaction; Bodenmann & Cina, 2006), partner experiences of stress can also affect one’s own experience in a relationship (referred to as dyadic stress; Bodenmann, 2005; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009; Story & Bradbury, 2004). Minor stressors (e.g., work demands) appear to have more of an influence on relationship functioning than major stressors (e.g., unemployment, severe illness; Bodenmann, 1995; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009), and it has been suggested that this is because minor stressors are more likely to contribute to relationship-compromising behaviors (e.g., ineffective communication, less time spent with one’s partner), whereas major stressors are more likely to bring couples together (Bodenmann, Ledermann, & Bradbury, 2007; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009).

Minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) describes the unique stressors that sexual minorities experience, including external stressors (e.g., discrimination, victimization) and internal stressors (e.g., internalized negative attitudes toward sexual minorities, expectations of rejection, sexual orientation concealment). In addition to explicit discrimination, sexual minorities can also experience microaggressions, or subtle behaviors that communicate negative attitudes toward marginalized groups (Nadal, Rivera, & Corpus, 2010). Consistent with minority stress theory, research has demonstrated the negative mental health consequences of discrimination and victimization (e.g., Bostwick, Boyd, Hughes, West, & McCabe, 2014), microaggressions (e.g., Swann, Minshew, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2016), internalized stigma (e.g., Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010), expectations of rejection (e.g., Feinstein, Goldfried, & Davila, 2012), and sexual orientation concealment (e.g., Meidlinger & Hope, 2014).

Initially, minority stress theory was proposed to explain mental health problems among sexual minorities (Meyer, 2003), but it has since been extended to describe the ways in which minority stress could impact relationship functioning and well-being among same-sex couples (LeBlanc, Frost, & Wight, 2015). First, one partner’s experience of minority stress could have a negative effect on the other partner’s experience in the relationship. For example, if one partner experiences frequent microaggressions, then it could lead to conflict in the relationship and the other partner could feel less satisfied. Given that minor stressors have more of an influence on relationship functioning than major stressors (Bodenmann, 1995; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009), minority stressors that are experienced in more subtle, everyday ways (e.g., encountering microaggressions, dealing with internalized stigma, deciding whether or not to conceal one’s sexual orientation) may have more of an influence on same-sex relationship functioning than more overt minority stressors (e.g., victimization). Additionally, both partners’ experiences of minority stress could interact to impact relationship functioning. For example, if both partners experience frequent microaggressions (referred to as stress concordance), then the negative impact of each individual’s stress could be exacerbated by their partner’s stress. Alternatively, if only one partner experiences frequent microaggressions (referred to as stress discordance), then this discrepancy could lead to conflict and reduced satisfaction. A meta-analysis found that sexual minority stress was associated with lower relationship well-being (Cao et al., 2017), but most of the studies focused on individuals, highlighting the need for research on couples.

Of note, a few studies have examined the associations between stress and relationship functioning among same-sex couples. For example, Mohr and Fassinger (2006) found that one’s own internalized stigma and stigma sensitivity were associated with lower relationship quality, and partner reports of stigma sensitivity were also associated with lower relationship quality (but only for male couples). Similarly, Otis, Rostosky, Riggle, and Hamrin (2006) found that one’s own general stress and internalized stigma were associated with lower relationship quality, and partner reports of internalized stigma were also associated with lower relationship quality. Additionally, although Jordan and Deluty (2000) found that discrepancies between partners in sexual orientation disclosure were associated with lower satisfaction among female couples, Mohr and Fassinger (2006) did not find support for discrepancies in individual and partner experiences (e.g., internalized stigma, stigma sensitivity) predicting relationship quality.

These studies provide support for partner-level influences of stress on same-sex relationship functioning, but important questions remain. First, these studies were conducted over a decade ago and there have been dramatic increases in support for same-sex relationships (Pew Research Center, 2017). It is important to examine whether minority stress continues to influence same-sex relationship functioning in the current sociocultural climate. Second, on average, participants in these studies were in their mid- to late-30s and had been in relationships for 5–7 years. It remains unclear if findings generalize to younger same-sex couples who have been together for less time. Given that relationship experiences during adolescence and early adulthood can have enduring effects into later adulthood (Collins et al., 2009), it is important to examine the impact of minority stress on relationship functioning among young same-sex couples. Third, these studies focused on a subset of minority stressors and a single aspect of relationship functioning. A more thorough examination is warranted to understand how different types of minority stress influence different aspects of relationship functioning.

Finally, there has been limited attention to individual differences in the associations between stress and relationship functioning among same-sex couples (i.e., moderators). Several theories propose that coping resources can reduce the negative impact of stress on relationship functioning (Karney & Neff, 2013; LeBlanc et al., 2015). The strategies that individuals use to help their partners cope with stress and those that couples use to cope with stress together (collectively referred to as dyadic coping) are particularly important to relationship functioning (Bodenmann, 2005; Falconier, Jackson, Hilpert, & Bodenmann, 2015). Dyadic coping is a stronger predictor of relationship satisfaction than individual coping (Papp & Witt, 2010) and it can reduce the negative impact of stress on relationship functioning (Breitenstein, Milek, Nussbeck, Davila, & Bodenmann, 2017; Falconier, Nussbeck, & Bodenmann, 2013). However, few studies have examined dyadic coping among sexual minorities. In exceptions, better dyadic coping was associated with more satisfaction and less conflict for both lesbian and heterosexual women in relationships (Meuwly, Feinstein, Davila, Garcia Nunez, & Bodenmann, 2013) and it reduced the association between minority stress and anxiety among female couples (Randall, Totenhagen, Walsh, Adams, & Tao, 2017). In sum, dyadic coping has the potential to buffer the negative effects of stress on relationship functioning, but it remains unclear if this extends to minority stress among young male couples.

The literature on relationship functioning also suggests that the negative impact of stress could depend on the length of the relationship. For example, the vulnerability-stress-adaptation model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995) proposes that stress can lead to relationship-compromising behaviors (e.g., negative interactions, reduced support), and the accumulation of these experiences over time can have a negative impact on relationship quality. Therefore, stress may have a more negative impact on relationship functioning for individuals in longer relationships because of the accumulation of stress and negative experiences over time. Alternatively, there is evidence that individuals in longer relationships are more resilient to the negative impact of stress on relationship functioning (Fraley & Shaver, 1998; Howe, Levy, & Caplan, 2004). Of note, a meta-analysis found that relationship length did not moderate the average association between sexual minority stress and relationship well-being (Cao et al., 2017). However, most of the studies focused on individuals rather than couples and relationship length was not tested as a moderator of the associations between specific types of minority stress and aspects of relationship functioning. Therefore, additional research is needed to understand the influence of relationship length on the association between stress and same-sex relationship functioning.

To address the gaps in previous research, the current study examined the associations between individual and partner experiences of stress and relationship functioning among young male same-sex couples. As part of a larger study, participants reported on general and minority stress (internalized stigma, microaggressions, victimization, and outness) and relationship functioning (satisfaction, trust, commitment, conflict, and negative communication behavior). First, we examined the actor and partner effects of stress on relationship functioning. We hypothesized that there would be significant actor and partner effects for general and minority stress. Next, we examined the interactions between individual and partner experiences of stress as predictors of relationship functioning. Given competing theoretical possibilities, we did not make a priori hypotheses about these analyses. Finally, we examined individual (i.e., actor) perceptions of dyadic coping and relationship length as moderators of the actor and partner effects. We hypothesized that stress would have a more negative impact on relationship functioning for individuals who reported lower dyadic coping, but we did not make a priori hypotheses about relationship length because of competing theoretical possibilities.

Method

Participants and Procedures

We used data from an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of multilevel influences on HIV and substance use among young MSM (current total N = 1,042). Young MSM were recruited from three previous cohorts to achieve a multiple cohort, accelerated longitudinal design (Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 1996). Cohort members were required to meet the following criteria: 16–29 years old, assigned male at birth, English-speaking, and identified as gay/bisexual or had sex with a man in the past year. We expanded the cohort by allowing members to recruit their serious partners at each visit. Partners who met the above criteria were eligible for enrollment. In contrast, partners who were assigned female at birth or older than 29 were eligible for a one-time visit. Cohort members could also refer three peers who were required to meet the same criteria.

Although our data came from a larger longitudinal study, the current analyses were cross-sectional; we used data from each couple’s first visit. Given that cohort members recruited their partners, there was a period of time in between partners’ assessments for most couples. The median length of time in between partners’ assessments was one week; 73% of partners were assessed within two weeks. A small subset (8%) had more than one month in between their assessments, of whom three couples had more than two months (62–98 days). We conducted sensitivity analyses to ensure that our results were not affected by the different amounts of time in between partners’ assessments. The sample started with 202 dyads, but 49 dyads were excluded because: partners came from a three-person relationship (n = 3 dyads); one partner was present in two different dyads at two different visits (i.e., they entered a new relationship), in which case we only included data from their first dyad (n = 20 dyads); one partner was a cisgender woman (n = 13 dyads); and partners did not agree that their relationship was serious (n = 13 dyads). Therefore, the analytic sample included 153 dyads (n = 306 individuals).

Participants in the analytic sample ranged from 16 to 54 years old (M = 23.06, SD = 4.75). The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was 35.0% Black/African American, 29.1% White, 28.1% Hispanic/Latino, and 7.8% other. Additionally, most participants identified as gay (78.1%), followed by bisexual (15.0%), and other (6.9%). In regard to education, 12.1% had not completed high school, 72.5% completed high school, 12.4% completed college, and 2.9% completed graduate school. Based on HIV testing at the couple’s first study visit, most participants were HIV-negative (79.7%), while 20.3% were HIV-positive. Relationship length ranged from less than one month to 7.58 years (M = 1.30 years, SD = 1.47 years) and 29.1% of participants reported that they lived with their partner. Most couples were concordant HIV-negative (71.2%), while 11.8% were concordant HIV-positive and 17.02% were discordant.

Data collection began in February 2015 and these analyses used data through September 2017. Participants completed a psychosocial survey, a network interview, and biomedical specimen collection. Most measures were administered to the full sample, but some were not administered at a specific visit or added after data collection had begun. Participants were compensated $50 per visit. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographics

Participants reported their age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, living situation, and relationship length. There was a strong correlation between partners’ reports of relationship length (r = .70, p < .001), so we used their mean for analyses. The means were highly correlated with individual reports (r = .92, p < .001).

General stress

Participants completed the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (Roberti, Harrington, & Storch, 2006), which asked, “In the past month, how often have you…?” Example items included: “Felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life” and “Felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them.” Items were rated on a 5-point scale (0 = never, 4 = very often), four items were reverse-scored, and responses were summed. Scores could range from 0 to 40 (α = .78) and no data were missing.

Victimization

Participants were asked, “In the past six months, how many times [item] because you are or were thought to be gay, bisexual, or transgender?” Items included: (1) have you been threatened with physical violence; (2) have you had an object thrown at you; (3) have you been punched, kicked, or beaten; (4) have you been threatened with a knife, gun, or another weapon; (5) has someone chased or followed you; and (6) has your property been damaged. Items were rated on a 4-point scale (0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = twice, 3 = three times or more). Responses were averaged, scores could range from 0 to 3 (α = .86), and no data were missing.

Microaggressions

Participants completed the six-item “anti-gay attitudes and expressions” subscale of the Sexual Orientation Microaggression Inventory (Swann et al., 2016). They were asked, “In the past 6 months, how often have you had the following experiences?” Example items include: “You heard someone say ‘that’s so gay’ in a negative way” and “Someone expressed a stereotype (e.g., “gay men are so good at fashion”).” Items were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a few times, 3 = about every month, 4 = about every week, 5 = about every day) and averaged. Scores could range from 1 to 5 (α = .86). No data were missing.

Internalized stigma

Participants completed a measure adapted from the Homosexual Attitudes Inventory (Nungesser, 1983) and the Internalized Homosexual Stigma Scale (Ramirez-Valles, Kuhns, Campbell, & Diaz, 2010). Puckett et al. (2017) identified three factors (desire to be heterosexual, fear of coming out, and fear of stereotypical perception). As recommended, we used the 8-item “desire to be heterosexual” subscale. Participants were asked how much they agreed with statements (e.g., “Sometimes I wish I were not gay”). Items were rated on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) and averaged. Scores could range from 1 to 4 (α = .89). This was administered to 280 participants (91.5%), because it was not administered at every visit. One participant was missing data.

Outness

Participants were asked, “How out are you to people around you?” (0 = not out to anyone, 1 = only out to a few select people, 2 = out to most people, 3 = out to everyone). This was administered to 280 participants (91.5%), because it was not administered at every visit. One participant was missing data.

Satisfaction, trust, and commitment

Participants were asked: (1) “How satisfied are you with your current relationship?” (2) “How much do you trust your partner?” and (3) “How committed are you to your relationship?” (Hendrick, 1988). Items were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much) and four participants were missing data for all three variables.

Conflict

Participants completed the 2-item conflict subscale of the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Busby, Christensen, Crane, & Larson, 1995): (1) “How often do you and your partner fight?” and (2) “How often do you and your partner get on each other’s nerves?” Items were rated on a 6-point scale (0 = never, 5 = all of the time). Responses were summed and scores could range from 0 to 10 (α = .76). This was administered to 159 participants (52.0%), because it was added after data collection had begun. No data were missing.

Negative communication behavior

Participants completed the 8-item negative communication subscale of the Communication Skills Test (Buzzella, Whitton, & Tompson, 2012b; Jenkins & Saiz, 1995; Whitton et al., 2007), which presented statements about communication with one’s partner. Example items include: “My partner insulted me” and “When my partner said something hurtful to me, I threw something negative right back.” Items were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = never happened, 7 = happened most of the time) and averaged. Scores could range from 1 to 7 (α = .88). This was administered to a 172 participants (56.2%), because it was added after data collection had begun. No data were missing.

Dyadic coping

Participants completed the 5-item common dyadic coping subscale of the Dyadic Coping Inventory (Bodenmann, 2008), which presented statements about what they do with their partner when they are both feeling stress (e.g., “We try to cope with the problem together and search for solutions” and “We help one another to put the problem in perspective and see it in a new light”). Items were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = very rarely, 5 = very often) and averaged. Scores could range from 1–5 (α = .87). This was administered to 159 participants (52.0%), because it was added after data collection had begun. No data were missing.

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 7 using robust maximum likelihood. Multilevel modeling was used to account for the non-independence of dyadic data. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML). FIML uses all available data, produces more accurate parameter estimates than listwise/pairwise deletion and mean substitution, and yields relatively unbiased parameters with moderate amounts of missing data (Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Schlomer, Bauman, & Card, 2010). For most models, the analytic sample ranged from 140–153 dyads (depending on how much missing data there were on the predictors). However, it ranged from 66–79 dyads for models that included dyadic coping

First, we examined the latent structure of relationship functioning using multilevel confirmatory factor analysis. Model fit was evaluated using the chi-squared goodness of fit test, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). A non-significant chi-squared test, CFI and TLI ≥ .95, and RMSEA < .06 indicate good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We identified two latent variables (described below): relationship quality (indicated by satisfaction, trust, and commitment) and negative relationship interactions (indicated by conflict and negative communication behavior).

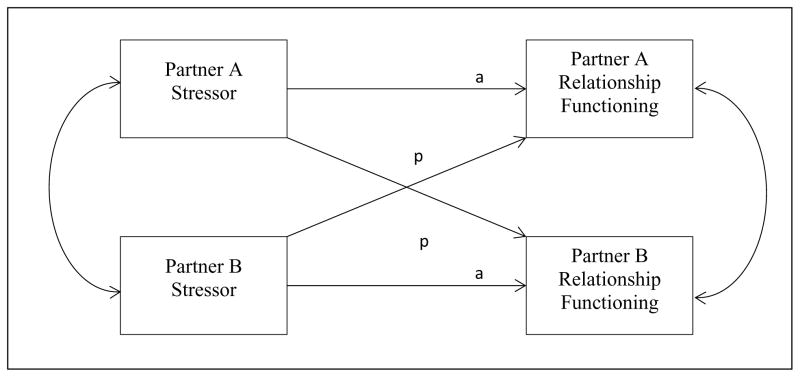

Second, we used multilevel structural equation modeling to estimate five Actor-Partner Interdependence Models—one for each stressor (see Figure 1; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006; Mustanski, Starks, & Newcomb, 2014). Separate models were tested for each stressor, but both latent variables for relationship functioning were included in each model. Dyad members were treated as indistinguishable. Therefore, a single actor effect (i.e., the actor’s outcome regressed on the actor’s predictor) and a single partner effect (i.e., the actor’s outcome regressed on the partner’s predictor) were estimated for each predictor/outcome pair. All models controlled for relationship length at the couple-level and all predictors were grand-mean centered.

Figure 1.

Actor-Partner Interdependence Model depicting the associations between stressors and relationship functioning; “a” represents actor effects; “p” represents partner effects; single-headed arrows represent predictive paths; double-headed arrows represent correlations.

Third, we tested three sets of interaction effects models: (1) interactions between individual and partner stress; (2) actor dyadic coping as a moderator of actor and partner effects; and (3) relationship length as a moderator of actor and partner effects. Each set of interaction effects models included five models (one for each stressor). Each model in the first set included one interaction (actor stress by partner stress), whereas each model in the second and third sets included two interactions (actor stress by moderator and partner stress by moderator). Both of the latent variables for relationship functioning were included in each model and relationship length was controlled for at the couple-level. We used the methods outlined in Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006) to decompose significant interactions (i.e., we examined the relevant effects at one standard deviation above and below the mean of the moderator).

In total, we tested 20 models (5 for main effects, 5 for actor by partner interactions, 5 for dyadic coping as a moderator, and 5 for relationship length as a moderator). To reduce the risk of Type I error, we used the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). This procedure uses the false discovery rate (i.e., the percentage of significant results that are likely to be Type I errors if no correction is made) and the total number of significance tests conducted to adjust the p-value for each significance test and to reduce the likelihood of Type I errors. Finally, we conducted three sets of sensitivity analyses to determine whether results were affected by: (1) couples with a transgender partner (n = 15); (2) couples with a partner over age 29 (n = 19); and (3) couples with more than two weeks between partners’ assessments (n = 41).

Results

Means, standard deviations, individual-level bivariate correlations, and intraclass correlations are presented in Table 1. Couple-level bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2. On average, participants reported low to moderate levels of stress and high levels of outness. Additionally, participants reported high levels of satisfaction, trust, commitment, and dyadic coping, and moderate levels of conflict and negative communication behavior. There were small to medium positive correlations among most of the stress variables. However, higher outness was associated with lower internalized stigma, but outness was not associated with the other stress variables. There were medium-to-large correlations among the relationship functioning variables in the expected directions. Longer relationship length was associated with less satisfaction, trust, and commitment, and more conflict and negative communication behavior.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, intraclass correlations, and individual-level bivariate correlations.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stressors | |||||||||||

| 1. General stress | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Internalized stigma | .21** | - | |||||||||

| 3. Microaggressions | .19* | .12* | - | ||||||||

| 4. Victimization | .10* | .12* | .32** | - | |||||||

| 5. Outness | −.07 | −.39** | −.10 | −.03 | - | ||||||

| Relationship functioning | |||||||||||

| 6. Satisfaction | −.35** | −.31** | −.12* | −.10 | .13* | - | |||||

| 7. Trust | −.23** | −.25** | −.12* | −.04 | .05 | .54** | - | ||||

| 8. Commitment | −.21** | −.12** | −.05 | −.13* | .01 | .57** | .34** | - | |||

| 9. Conflict | .19* | .20** | .08 | .06 | −.25** | −.46** | −.41** | −.40** | - | ||

| 10. Negative communication | .32** | .26** | .19* | .11 | −.25** | −.56** | −.52** | −.39** | .55** | - | |

| 11. Dyadic coping | −.15* | −.18* | −.01 | −.08 | .17* | .52** | .37** | .31** | −.33** | −.46** | - |

|

| |||||||||||

| Mean | 16.9 | 1.65 | 2.33 | .83 | 2.43 | 4.31 | 4.22 | 4.51 | 3.82 | 2.91 | 3.96 |

| Standard Deviation | 6.25 | .64 | .82 | 1.45 | .75 | .90 | .99 | .89 | 2.37 | 1.15 | .93 |

| Range | 0–40 | 1–4 | 1–5 | 0–3 | 0–3 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 0–10 | 1–7 | 1–5 |

| ICC | .13 | .28 | .10 | .32 | .17 | .30 | .15 | .20 | .46 | .42 | .21 |

Notes. ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient;

p < .05;

p < .01.

Table 2.

Couple-level bivariate correlations.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship functioning | ||||||

| 1. Satisfaction | - | .62** | .75** | −.33** | −.45** | −.38** |

| 2. Trust | - | .55** | −.37** | −.52** | −.90** | |

| 3. Commitment | - | .15* | −.12* | −.40** | ||

| 4. Conflict | - | .93** | .34* | |||

| 5. Negative communication | - | .51** | ||||

| 6. Length | - | |||||

Note. Couple-level bivariate correlations are only presented for variables examined at the couple-level in the APIMs. As individual-level predictors and moderators are not included at the couple level in APIMs (e.g., Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006), couple-level correlations are not presented for these variables.

p < .05;

p < .01

Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis

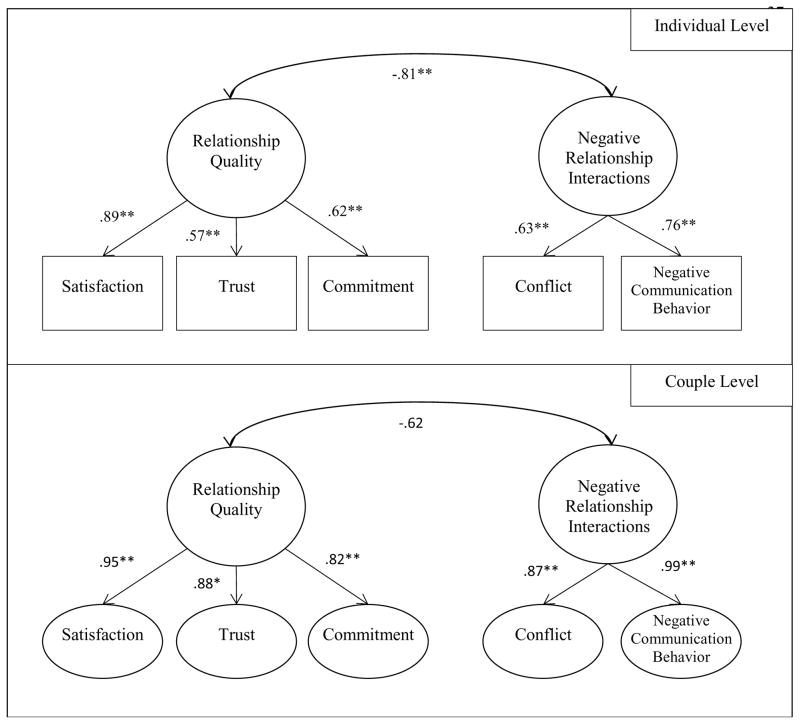

Relationship functioning was modeled as two correlated latent variables: relationship quality (indicated by satisfaction, trust, and commitment) and negative relationship interactions (indicated by conflict and negative communication behavior). The model fit the data well (χ2[8] = 15.28, p = .054, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .98, TLI = .95; see Figure 2). At the individual-level, standardized factor loadings ranged from .57 to .89. Individuals who reported higher satisfaction reported higher trust and commitment (relative to the couple’s average levels), and individuals who reported higher conflict reported higher negative communication behavior (relative to the couple’s average levels). At the couple-level, standardized factor loadings ranged from .82 to .99. Couples with higher average satisfaction had higher average trust and commitment, and couples with higher average conflict had higher average negative communication behavior. There was a negative correlation between relationship quality and negative relationship interactions at the individual-level (r = −.81, p < .001). There was also a negative correlation at the couple-level, but it was not significant (r = −.62, p = .22).

Figure 2.

Measurement model for relationship functioning. Standardized factor loadings are presented.

* p < .05; **p < .01

Main Actor and Partner Effects

Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented in Table 3. The actor effects of general stress and internalized stigma on relationship quality were significant. Participants who reported higher general stress and internalized stigma had lower relationship quality. Additionally, the actor effects of general stress, internalized stigma, microaggressions, and outness on negative relationship interactions were significant. Participants who reported higher general stress, internalized stigma, and microaggressions, and lower outness, had more negative relationship interactions. None of the other actor effects were significant. The partner effect of internalized stigma on negative relationship interactions was significant. Having a partner who reported higher internalized stigma was associated with more negative relationship interactions. None of the other partner effects were significant.

Table 3.

Actor and partner effects of stress on relationship functioning.

| Predictor | Actor Effect | Partner Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | |

| Relationship Quality | ||||

| General stress | −.04 (.01) | < .001 | −.002 (.01) | .89 |

| Internalized stigma | −.34 (.11) | .01 | −.11 (.13) | .45 |

| Microaggressions | −.11 (.06) | .20 | .01 (.06) | .89 |

| Victimization | −.07 (.05) | .21 | .05 (.03) | .89 |

| Outness | .11 (.07) | .21 | .12 (.07) | .45 |

| Negative relationship interactions | ||||

| General stress | .08 (.02) | < .001 | .02 (.02) | .69 |

| Internalized stigma | .53 (.22) | .04 | .65 (.21) | .03 |

| Microaggressions | .65 (.21) | .01 | .35 (.25) | .60 |

| Victimization | .15 (.12) | .37 | .06 (.11) | .60 |

| Outness | −.66 (.21) | .01 | −.40 (.24) | .60 |

Notes. Values are unstandardized regression coefficients, p values have been corrected using Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Bold values indicate significant effects at p < .05.

Interaction Effects

None of the interactions between individual and partner stress were significant (results not presented). Similarly, dyadic coping did not moderate any actor or partner effects (results not presented). However, at the individual-level, there were significant main effects of dyadic coping on relationship quality (b = .56, SE = .07, z = 7.64, p < .001) and negative relationship interactions (b = −.53, SE = .09, z = −6.06, p = .001). Participants who reported higher dyadic coping had higher relationship quality and less negative relationship interactions. At the couple-level, there were significant main effects of relationship length on relationship quality (b = −1.04, SE = .26, z = −4.02, p < .001) and negative relationship interactions (b = .57, SE = .18, z = 3.19, p = .001). Couples in longer relationships had lower relationship quality and more negative relationship interactions. Relationship length moderated the actor effect of general stress on relationship quality (b = −.01, SE = .005, p = .007) and the actor effect of internalized stigma on relationship quality (b = −.22, SE = .06, p = .004). Participants who reported higher general stress had lower relationship quality in longer relationships (b = −.11, SE = .02, z = −4.89, p < .001), but not in shorter relationships (b = .02, SE = .02, z = −.93, p = .35). Similarly, participants who reported higher internalized stigma had lower relationship quality in longer relationships (b = −1.44, SE = .30, z = −4.82, p < .001), but not in shorter relationships (b = .59, SE = .31, z = 1.90, p = .06). Relationship length did not moderate any other effects (results not presented).

Sensitivity Analyses

The pattern of results remained the same excluding couples with a transgender partner, couples with a partner over age 29, and couples with more than two weeks in between partners’ assessments (i.e., all of the significant effects remained significant).

Discussion

Despite substantial evidence that sexual minorities experience unique stress related to their sexual orientation (Meyer, 2003), there has been very limited attention to minority stress among same-sex couples. To address this, we examined the associations between individual and partner experiences of general and minority stress and relationship functioning among young male couples. We also tested whether individual and partner experiences of stress interacted to predict relationship functioning, and dyadic coping and relationship length as moderators of the actor and partner effects. Overall, we found strong support for the actor effects of general and minority stress on relationship functioning, especially negative relationship interactions. In contrast, we found limited support for partner effects, no support for interactions between individual and partner experiences of stress, and no support for dyadic coping as a stress buffer.

In regard to actor effects, higher general stress and internalized stigma were associated with lower relationship quality, but only for those in longer relationships. Additionally, higher general stress and internalized stigma, more frequent microaggressions, and less openness about one’s sexual orientation were associated with more negative relationship interactions regardless of relationship length. These findings are consistent with evidence that general stress and internalized stigma have a negative impact on same-sex relationship functioning (e.g., Mohr & Fassinger, 2006; Otis et al., 2006). Despite increases in support for same-sex relationships (Pew Research Center, 2017), minority stress continues to have a negative impact on relationship functioning among young male couples. All of the stressors except for victimization were associated with negative relationship interactions. Previous research has demonstrated that minor stressors have more of an influence on relationship functioning than major stressors, which may be due to major stressors being more likely to bring couples together (Bodenmann et al., 2007; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009; Story & Bradbury, 2004). It is possible that victimization is experienced as more of a major stressor than general stress and other types of minority stress, but this remains an empirical question.

Our findings raise questions about the extent to which different types of stress influence different aspects of relationship functioning over the course of relationships. Specifically, our findings suggest that some minority stressors (e.g., microaggressions, outness) may have more of an influence on negative relationship interactions than relationship quality. Given that various factors influence relationship quality (Finkel, Simpson, & Eastwick, 2017), positive aspects of relationships (e.g., intimacy, passion) may offset the negative impact of some stressors on the quality of one’s relationship, even if they contribute to conflict. However, our findings also suggest that general stress and internalized stigma still contribute to lower relationship quality for those in longer relationships. These findings are consistent with the vulnerability-stress-adaptation model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995), which proposes that the accumulation of stress and negative relationship experiences over time can lead to reduced relationship quality. Further, the nature of relationships changes across development (e.g., from adolescence to adulthood) and the duration of a given relationship. Romantic partners assume a more central role and relationships become more interdependent over time (Lantagne & Furman, 2017). Therefore, internalized stigma may present greater challenges at later stages of relationships because of an increased emphasis on integrating one’s partner into other aspects of one’s life.

Of note, our findings do not address the mechanisms underlying the associations between stress and relationship functioning. In the broader relationship literature, two primary mechanisms have been proposed. First, stress can reduce the amount of time spent on relationship maintenance (Karney & Neff, 2013). Stress outside of one’s relationship requires time to address and spending time dealing with stress can reduce the amount of time partners spend on activities that nourish their relationship (e.g., physical intimacy; Karney & Neff, 2013). Second, stress can impair self-regulation processes. Ego depletion theories (Baumeister, 2002) propose that self-control is a limited resource that can be depleted through use. As such, stress can deplete cognitive and emotional resources, leading to less effective behavior within one’s relationship. Minority stress may also influence relationship functioning through additional mechanisms. Internalized stigma is associated with fear of intimacy (Szymanski & Hilton, 2013) and less effort to maintain one’s relationship in the face of conflict (Gaines et al., 2005), both of which could account for the association between internalized stigma and relationship functioning. It will be important for future research to examine the mechanisms underlying these associations, including whether they differ for general versus minority stress.

We found very limited support for partner effects of stress on relationship functioning. Having a partner who reported higher internalized stigma was associated with more negative relationship interactions, but none of the other partner effects were significant. There are a number of possible explanations for this finding that merit examination in future research. A partner who has internalized negative attitudes toward sexual minorities could be perceived by their partner as being ashamed of their same-sex relationship and this could lead to conflict. It is also possible that partner internalized stigma could impede relationship-promoting behaviors (e.g., expressions of intimacy), leading to conflict. Again, these remain empirical questions. Although we found a significant partner effect of internalized stigma on negative relationship interactions, this did not extend to relationship quality. This is in contrast to two previous studies, both of which found that partner internalized stigma was associated with lower relationship quality (Mohr & Fassinger, 2006; Otis et al., 2006). On average, our participants were younger and in relationships for less time than their participants. It is possible that partner internalized stigma does not have an impact on the overall quality of one’s relationship at this age.

The fact that none of the other partner effects were significant is inconsistent with research on different-sex couples (e.g., Bodenmann, 2005; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009; Story & Bradbury, 2004), but most studies focused on cohabitating and/or married adult couples. In a recent study, individual and partner experiences of stress outside the relationship were associated with more stress within the relationship and lower relationship quality for adult couples, but not adolescent couples (ages 16–22; Breitenstein et al., 2017). Given that the adolescent couples were not cohabitating, the authors suggested that they may have been better able to protect their relationships from daily hassles and to focus on positive aspects of their relationships. Developmental theories emphasize the self-focused nature of adolescents (Laursen & Jensen Campbell, 1999) and emerging adults (Arnett, 2007). As individuals mature and relationships become more interdependent, individuals shift toward emphasizing mutual rather than personal gains (Laursen & Jensen Campbell, 1999). In fact, one’s partner may not become an attachment figure or a recipient of caregiving until a relatively long relationship develops in late adolescence or early adulthood (Furman & Wehner, 1997). Therefore, partner stress may have more of an influence on relationship functioning at later stages of development. Given that most of our participants were 16–29 years old, we may have found limited support for partner effects because of their developmental stage.

Additionally, we did not find support for individual and partner experiences of stress interacting to predict relationship functioning. This is consistent with Mohr and Fassinger (2006), but Jordan and Deluty (2000) found that discrepancies in sexual orientation disclosure were associated with less satisfaction among female couples. Of note, most of our participants were out to most or all people in their lives, and it is possible that discrepancies in outness between partners were not associated with relationship functioning for this reason. It will be important to continue to examine this in samples that include more participants who are less open about their sexual orientation. Further, it is possible that the age of our participants contributed to our lack of support for individual and partner experiences interacting to predict relationship functioning. Again, individual and partner experiences of stress may have more of an influence on one another at later stages of development as individuals becomes more focused on mutual benefits in relationships.

Finally, despite evidence that dyadic coping can reduce the negative impact of stress on relationship functioning among different-sex couples (Breitenstein et al., 2017; Falconier et al., 2013), we did not find support for dyadic coping as a stress buffer. Dyadic coping can refer to the strategies that individuals use to help their partners cope with stress or to the strategies that couples use to cope with stress together (the latter of which are referred to as common dyadic coping; Bodenmann, 2005; Falconier et al., 2015). In contrast to Breitenstein et al. (2017), we focused on common dyadic coping and assessed it as a trait rather than a response to a specific stressor. It is possible that our participants did not share their experiences of stress with each other (precluding the use of common dyadic coping) or that they did not use common dyadic coping strategies in response to the specific stressors. Although Falconier et al. (2013) also focused on common dyadic coping, they found that it buffered the effects of female partners’ stress, but not male partners’ stress, which they attributed to gender differences in interpersonal orientation and coping. Regardless, we found that higher dyadic coping was associated with higher relationship quality and less negative relationship interactions, suggesting that it has an influence on same-sex relationship functioning even if it does not function as a stress buffer.

Clinical Implications

These findings have important implications for interventions with young male couples. Relationship education programs, which promote healthy relationships by teaching effective communication and conflict resolution skills, have been shown to improve relationship outcomes among different-sex couples (Hawkins, Blanchard, Baldwin, & Fawcett, 2008). In recent years, relationship education programs have been adapted for same-sex couples and similar positive effects have been demonstrated (Buzzella, Whitton, & Tompson, 2012a; Whitton, Weitbrecht, Kuryluk, & Hutsell, 2016). Relationship education has also been combined with HIV prevention to address the unique relationship and sexual health concerns facing young male same-sex couples (Newcomb et al., 2017). In addition to teaching effective communication and conflict resolution skills, these adapted programs address the unique stressors that same-sex couples experience as well as individual and dyadic strategies for coping with these stressors. The current findings support the need for relationship education programs for young male same-sex couples in order to address the influences of general and minority stress on relationship functioning.

Our findings suggest that individual stress has more of an influence on relationship functioning than partner stress among young male couples. As such, young male couples may benefit from learning individual coping skills to limit the extent to which their own stress impacts their relationships (e.g., not relying exclusively on one’s partner for support). Given that dyadic coping was associated with better relationship functioning, they may also benefit from learning skills to support their partner through stress (e.g., active and empathic listening) and to join together to respond to mutual stressors. Further, given that partners become more interdependent over time, education focused on dyadic coping skills may prevent the onset of future negative relationship outcomes. The fact that dyadic coping did not buffer the negative effects of stress suggests that young male couples may need guidance on which specific coping skills are likely to be most effective in different situations. For example, problem-solving may not be effective for situations in which a stressor is unlikely to change (e.g., if family members disapprove of same-sex relationships). Finally, for members of young male couples whose partners have internalized negative beliefs about sexual minorities, it may be important to increase awareness of the ways in which partner internalized stigma influences conflict and negative communication behavior as well as to learn skills to cope with this situation (e.g., problem-solving, acceptance). In sum, clinicians are encouraged to assess each partner’s levels of stress and to consider the extent to which both might be contributing to relationship problems.

Limitations

Findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, several measures were not administered to the full sample and we may have been underpowered to detect significant effects, especially for dyadic coping. Second, several constructs were assessed with single-item measures. Our use of latent variables reduced measurement error for relationship functioning, but we also used a single-item measure for outness. However, previous studies have used single-item measures of outness (e.g., Pachankis, Cochran, & Mays, 2015) and research has demonstrated strong correlations between single- and multiple-item measures of outness (Meidlinger & Hope, 2014). Third, scholars have argued that research on microaggressions is underdeveloped and lacks sufficient conceptual and methodological rigor (Lilienfeld, 2017). These concerns highlight the need for research focused on defining and measuring microaggressions. Fourth, our analyses were cross-sectional and it will be important for longitudinal research to examine bidirectional associations. Fifth, our data do not address the mechanisms underlying the associations between stress and relationship functioning. It will be important for future research to examine whether the mechanisms are the same for general versus minority stress, and whether the associations differ based on other characteristics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, cohabitation). Finally, our measures were self-report and research using diverse methods (e.g., observational measures of relationship functioning) has the potential to improve our understanding of same-sex relationship functioning.

Limitations aside, our findings suggest that individual experiences of general and minority stress continue to have a negative influence on same-sex relationship functioning even in the current sociocultural context. Although we found limited support for partner effects, partner internalized stigma was associated with negative relationship interactions. This was one of the first studies to examine actor and partner effects of minority stress on relationship functioning among young male couples and it was the first study to our knowledge to examine dyadic coping and relationship length as moderators. Additional research is needed to replicate findings and to examine the mechanisms through which individual and partner experiences of stress influence same-sex relationship functioning. In sum, our findings highlight the importance of considering general and minority stress in the context of same-sex relationships and point to directions for future research to improve our understanding of dyadic minority stress processes.

Public Health Significance Statements.

This study demonstrates that individual experiences of general and minority stress have a negative influence on relationship functioning among young male same-sex couples, especially for longer relationships.

This study found limited support for partner stress having an influence on relationship functioning with the exception that having a partner with higher internalized stigma was associated with more negative relationship interactions.

These findings support the need for interventions to address the negative impacts of general and minority stress on relationship functioning among young male same-sex couples.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (U01DA036939; PI: Mustanski). Brian A. Feinstein’s time was also supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (F32DA042708). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

References

- Baumeister RF. Ego depletion and self-control failure: An energy model of the self’s executive function. Self and Identity. 2002;1:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. A systemic-transactional view of stress and coping in couples. Swiss Journal of Psychology. 1995;54:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington, DC: APA; 2005. pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. Dyadic Coping Inventory. Manual. Bern, Switzerland: Huber; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Cina A. Stress and coping among stable-satisfied, stable-distressed, and separated/divorced Swiss couples: A 5-year prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage. 2006;44:71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Ledermann T, Bradbury TN. Stress, sex, and satisfaction in marriage. Personal Relationships. 2007;14:407–425. [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, West BT, McCabe SE. Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:35–45. doi: 10.1037/h0098851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitenstein CJ, Milek A, Nussbeck FW, Davila J, Bodenmann G. Stress, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction in late adolescent couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0265407517698049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busby DM, Christensen C, Crane DR, Larson JH. A revision of The Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: Construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1995;21:289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzella BA, Whitton SW, Tompson MC. The initial evaluation of a relationship education program for male same-sex couples. Couple and Family Psychology. 2012a;14:306–322. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzella BA, Whitton SW, Tompson MC. A preliminary evaluation of a relationship education program for male same-sex couples. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012b;1:306–322. [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Zhou N, Fine M, Liang Y, Li J, Mills-Koonce WR. Sexual minority stress and same-sex relationship well-being: A meta-analysis of research prior to the U.S. nationwide legalization of same-sex marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2017;17:1258–1277. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh GS, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Hops H. Analysis of longitudinal data within accelerated longitudinal designs. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconier MK, Jackson JB, Hilpert P, Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;42:28–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconier MK, Nussbeck F, Bodenmann G. Immigration stres and relationship satisfaction in Latino couples: The role of dyadic coping. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2013;32:813–843. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Goldfried MR, Davila J. The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:917–927. doi: 10.1037/a0029425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, Simpson JA, Eastwick PW. The Psychology of Close Relationships: Fourteen Core Principles. Annual Review of Psychology. 2017;68:383–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Airport separations: A naturalistic study of adult attachment dynamics in separating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1198–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Wehner EA. Adolescent romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1997;78:21–36. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219977804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines SO, Henderson MC, Kim M, Gilstrap S, Yi J, Rusbult CE, Hardin DP, Gaertner L. Cultural value orientations, internalized homophobia, and accommodation in romantic relationships. Journal of Homosexuality. 2005;50:97–117. doi: 10.1300/J082v50n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AJ, Blanchard VL, Baldwin SA, Fawcett EB. Does marriage and relationship education work? A meta-analytic study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:723–734. doi: 10.1037/a0012584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS. A Generic Measure of Relationship Satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Howe GW, Levy ML, Caplan RD. Job loss and depressive symptoms in couples: common stressors, stress transmission, or relationship disruption? Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:639–650. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins N, Saiz CC. The Communication Skills Test. University of Denver; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KM, Deluty RH. Social support, coming out, and relationship satisfaction in lesbian couples. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2000;4:145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Neff LA. Couples and stress: How demands outside a relationship affect intimacy within the relationship. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships. Oxford: Oxford University; 2013. pp. 664–684. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lantagne A, Furman W. Romantic relationship development: The interplay between age and relationship length. Developmental Psychology. 2017;53:1738–1749. doi: 10.1037/dev0000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Jensen-Campbell LA. The nature and functions of social exchange in adolescent romantic relationships. In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. New York: Cambridge University; 1999. pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc AJ, Frost DM, Wight RG. Minority stress and stress proliferation among same-sex and other marginalized couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015;77:40–59. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. Microaggressions. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2017;12:138–169. doi: 10.1177/1745691616659391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meidlinger PC, Hope DA. Differentiating disclosure and concealment in measurement of outness for sexual minorities: The Nebraska Outness Scale. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1:489–497. [Google Scholar]

- Meuwly N, Feinstein BA, Davila J, Garcia Nunez D, Bodenmann D. Relationship quality among Swiss women in opposite-sex versus same-sex romantic relationships. Journal of Swiss Psychology. 2013;72:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, Fassinger RE. Sexual orientation identity and romantic relationship quality in same-sex couples. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:1085–1099. doi: 10.1177/0146167206288281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Starks T, Newcomb ME. Methods for the design and analysis of relationship and partner effects on sexual health. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43:21–33. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0215-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Rivera DP, Corpus MJH. Sexual orientation and transgender microagressions: Implications for mental health and counseling. In: Sue DW, editor. Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact. Hoboken: Wiley; 2010. pp. 217–240. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Macapagal KR, Feinstein BA, Bettin E, Swann G, Whitton SW. Integrating HIV prevention and relationship education for young same-sex male couples: A pilot trial of the 2GETHER intervention. AIDS & Behavior. 2017;21:2464–2478. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1674-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nungesser LG. Homosexual acts, actors, and identities. New York: Praeger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Otis MD, Rostosky SS, Riggle EDB, Hamrin R. Stress and relationship quality in same-sex couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2006;23:81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Cochran SD, Mays VM. The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83:890–901. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp LM, Witt NL. Romantic partners’ individual coping strategies and dyadic coping: Implications for relationship functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:551–559. doi: 10.1037/a0020836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Changing attitudes on gay marriage. 2017 Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/changing-attitudes-on-gay-marriage/

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Swann G, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and perceived stigma: A validation study of stigma measures in a sample of young MSM. Sexuality Research & Social Policy. 2017;14:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s13178-016-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J, Kuhns LM, Campbell RT, Diaz RM. Social integration and health: community involvement, stigmatized identities, and sexual risk in Latino sexual minorities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:30–47. doi: 10.1177/0022146509361176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall AK, Bodenmann G. The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall AK, Totenhagen CJ, Walsh KJ, Adams C, Tao C. Coping with workplace minority stress: Associations between dyadic coping and anxiety among women in same-sex relationships. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2017;21:70–87. doi: 10.1080/10894160.2016.1142353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberti JW, Harrington LN, Storch EA. Further psychometric support for the 10 item version of the Perceived Stress Scale. Journal of College Counseling. 2006;9:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Bauman S, Card NA. Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0018082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story LB, Bradbury TN. Understanding marriage and stress: essential questions and challenges. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;23:1139–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann G, Minshew R, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Validation of the Sexual Orientation Microagression Inventory in a diverse sample of LGBT youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2016;45:1289–1298. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0718-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Hilton AN. Fear of intimacy as a mediator of the internalized heterosexism-relationship quality link among men in same-sex relationships. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2013;35:760–772. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Olmos-Gallo PA, Stanley SM, Prado LM, Kline GH, St Peters M, Markman HJ. Depressive symptoms in early marriage: predictions from relationship confidence and negative marital interaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:297–306. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Weitbrecht EM, Kuryluk AD, Hutsell DW. A Randomized Waitlist-Controlled Trial of Culturally Sensitive Relationship Education for Male Same-Sex Couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2016;30:763–768. doi: 10.1037/fam0000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]