Abstract

Objectives

Biofilms may contribute to refractory chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), as they lead to antibiotic resistance and failure of effective clinical treatment. L-methionine is an amino acid with reported biofilm inhibiting properties. Ivacaftor is a CFTR potentiator with mild antimicrobial activity via inhibition of bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. The objective of this study is to evaluate whether co-treatment with ivacaftor and L-methionine can reduce the formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms.

Methods

P. aeruginosa (PAO-1 strain) biofilms were studied in the presence of L-methionine and/or ivacaftor. For static biofilm assays, PAO-1 was cultured in a 48-well plate for 72 hours with stepwise combinations of these agents. Relative biofilm inhibitions were measured according to optical density of crystal violet stain at 590 nm. Live/dead assays (BacTiter-Glo™ assay, Promega) were imaged with laser scanning confocal microscopy. An agar diffusion test was used to confirm antibacterial effects of the drugs.

Results

L- methionine (0.5 μM) significantly reduced PAO1 biofilm mass (32.4 ± 18.0 %, n=4, p<0.001) compared to controls. Low doses of ivacaftor alone (4, 8, 12 μg/ml) had no effect on biofilm formation. When combined with ivacaftor (4 μg/ml), synergistic anti-biofilm effect was noticed at 0.05 μM and 0.5 μM of L-methionine (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.0415) compared to corresponding concentrations of L-methionine alone.

Conclusion

Ivacaftor enhanced the anti-biofilm activity of L-methionine against the PAO-1 strain of P. aeruginosa. Further studies evaluating the efficacy of ivacaftor/L-methionine combinations for P. aeruginosa sinusitis are planned.

Keywords: Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, L-methionine, Ivacaftor, Biofilm, Chronic Rhinosinusitis, Sinusitis, CFTR, Cystic Fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a chronic airway disease defined as persistent inflammation and infection of the nasal and sinus mucosa.1 Mounting evidence suggests that biofilms may contribute to the pathophysiology of recalcitrant CRS.2-5 Bacterial biofilm-positive CRS patients exhibit worse sinus symptoms and require multiple courses of antibiotic treatment.4 In particular, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus biofilms are known to confer poor clinical improvement following surgical intervention.2 Biofilms create an inhospitable environment for antibiotic potency by downregulating the metabolic activity of “core” bacteria and creating a milieu conducive for antibiotic resistance.6 Bacteria residing in biofilms are difficult to eradicate with antibiotics at standard doses, even when topical irrigation is considered. A rabbit model with P. aeruginosa sinusitis required tobramycin at approximately 400x the mean inhibitory concentration to eradicate the infection.7 Such high doses can be ineffective in the long-term due to the heightened risk of the emergence of new antibiotic resistant strains as well as the risk of systemic side effects.

To treat bacterial biofilms without using such intense drug therapies, alternative approaches with unconventional agents that disrupt or inhibit biofilms have garnered significant attention.8,9 Amino acids, such as D-amino acids and L-tryptophan are commonly secreted by biofilms during later stages of development and have been amongst several agents recently studied for their potential anti-biofilm activity.10-13 D-amino acids are effective at disassembling existing biofilms, whereas L- tryptophan inhibits the formation of biofilms. L-methionine was recently shown to inhibit the formation of P. aeruginosa biofilms at low concentrations (0.5 μM) by increasing DNase activity and degrading extracellular DNA, which is required for biofilm formation. In addition, ivacaftor, a cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) potentiator that enhances Cl− secretion in airway epithelia14-18, was recently identified to have potentially beneficial off-target effects as a weak inhibitor of bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV.19,20 Alternative antibacterial agents against P. aeruginosa may provide a viable treatment option without risks of antibacterial resistance or antibiotic-related complications. The objective of the current study is to evaluate whether ivacaftor enhances the anti-biofilm activity of L-methionine against P. aeruginosa.

METHODS

Drugs

L-methionine (98+%, Acros Organics, Belgium, NJ) was added to Luria-Bertani (LB)-Miller broth (Fisher Scientific, Bridgewater, NJ) and immediately diluted to desired concentrations. Ivacaftor (VX-770; Selleckchem, Houston, TX) was dissolved in DMSO to create a stock solution (10 mg/ml).

Preparation of PAO-1 wild type P. aeruginosa Biofilm

P. aeruginosa (PAO-1 strain) was expanded from glycerol frozen stock by inoculating 50 ml of LB broth followed by growth overnight at 37°C on a shaker at 200 rpm. Cultures were streaked on LB agar plates according to the quadrant method and grown in a static incubator at 37°C overnight at least twice to confirm conformity of cultures. From the plate, an isolated colony was grown in 10 ml of LB-Miller broth at 37°C on a shaker at 200 rpm overnight. Cultures were diluted with fresh LB-Miller broth to an inoculation concentration of 1×104. Biofilm experiments were performed in a 48-well plate where 800 μl total LB-Miller broth containing different concentrations of L-methionine and ivacaftor were incubated at 30 °C for 72 hours. To evaluate impact on pre-existing biofilm mass, drugs were administered to the 48-well plate after 72 hours of bacterial incubation. Adequate biofilm growth for the positive control well was defined as a mean optical density (OD) 600 difference (OD600 at 6 h minus OD600 at 0 h) higher than 0.05.21

Crystal violet (CV) staining of biofilms

Crystal violet staining was used to quantify PAO-1 biofilms.22 Briefly, after the incubation period, the media in each well was gently aspirated with a pipette and then rinsed in DI water 3 times to remove excess liquid and bacterial debris. After letting plates air dry, 900 μL of 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet diluted in DI water was added to the wells for 20 minutes at room temperature. The crystal violet was then aspirated by pipette and washed again three times in DI water to remove excess stain. Stain was dissolved using 900 μL of 30% acetic acid and the absorbance read at 590 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy HK, BIO-TEK Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Agar Diffusion Test

PAO-1 cultures were grown overnight to a concentration of 2 × 106. 100 μL of the culture was spread onto 100 mm petri dishes (Fisher Scientific, no. FB0875712) using 30 mm cell spreaders (Fisher Scientific, no. 08-100-10) on Mueller-Hinton agar (BD chemical, ref: 225250). Blank diffusion disks (ThermoFisher, ref: R55054) were soaked in pure LB broth, or LB broth with the desired drug concentrations of L-methionine and ivacaftor for 15 min before being transferred onto the agar with forceps. Plates were incubated at 30 °C overnight and measured the next day.

Bacterial Biofilm Viability

At the desired concentrations of L-methionine and ivacaftor, PAO-1 was cultured for 24 hours on 14mm glass coverslips within a 35mm dish (MatTek, Ashland, MA). PAO-1 biofilms were stained with SYTO9 and propidium iodide (PI) staining (BacLight™ Live/Dead Bacterial Viability Kit; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The viability was measured with confocal laser scanning microscopy (A1R, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and image analyses were performed with ImageJ national institute of health (NIH) image processing software.23 The quantitative structural parameters of the biofilms such as volume and thickness, were extracted from confocal stack images and analyzed. The average z-stacks of 1 μm were acquired from each biofilm horizontal plane with a maximum of five stacks at different fields of view. The quantification of biomass, representing overall volume of cells in the biofilm was carried out using free bioImage_L (www.bioimagel.com. Malmö, Sweden).24

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed at least 4 independent times. Normalized values for relative biofilm quantification were expressed as ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses were conducted with an included statistical tool of GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (La Jolla, Ca). For evaluating the combined effects of L-methionine and ivacaftor, a one-way ANOVA was performed with a post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test with significance set at p < 0.05. For comparing the effects between different L-methionine concentrations, a two-way ANOVA was performed with a Tukey’s multiple comparison test with significance set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Anti-biofilm activity of L-methionine and ivacaftor against PAO-1 biofilms

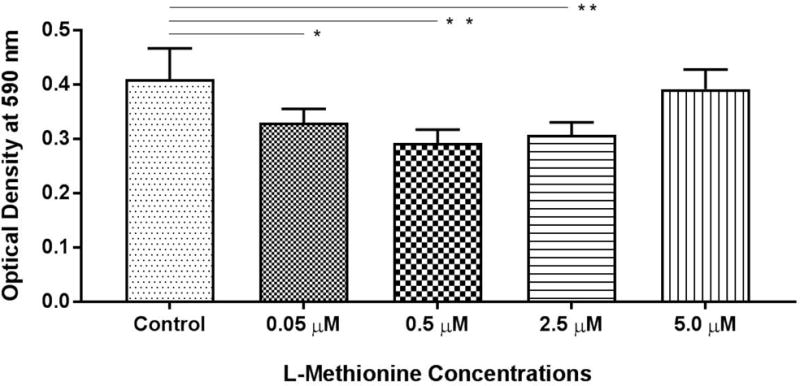

To determine the anti-biofilm activity of L-methionine against PAO-1 biofilms, escalating concentrations of 0.05, 0.5, 2.5, and 5 μM of L-methionine were used (Figure 1). Compared to control, statistically significant anti-biofilm activity was noted at concentrations of 0.05, 0.5 and 2.5 μM of L-methionine (p = 0.036, 0.003, 0.009, respectively). The highest dose-specific inhibition of biofilm growth was observed with 0.5 μM L-methionine (OD590 0.29 ± 0.03), significantly lower than controls (OD590 0.41 ± 0.06) (p = 0.003) (Figure 1), which was consistent with previous studies.13 Anti-biofilm activity diminished as the concentration of L-methionine increased from 2.5 μM (OD590 0.307 ± 0.023, p=0.009) to 5 μM (OD590 0.39 ± 0.033, p = 0.9).

Figure 1. Effect of L-methionine on PAO1 Biofilm formation.

Dose-dependent inhibition of PAO-1 biofilm growth was observed at 0.05, 0.5, and 2.5 μM L-methionine, with the largest difference occurring at 0.5 μM.

* represents statistical significance of p<0.05. ** represents statistical significance of p<0.01 when compared to the control condition. Analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA tests with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. All conditions consisted of at least 4 experiments.

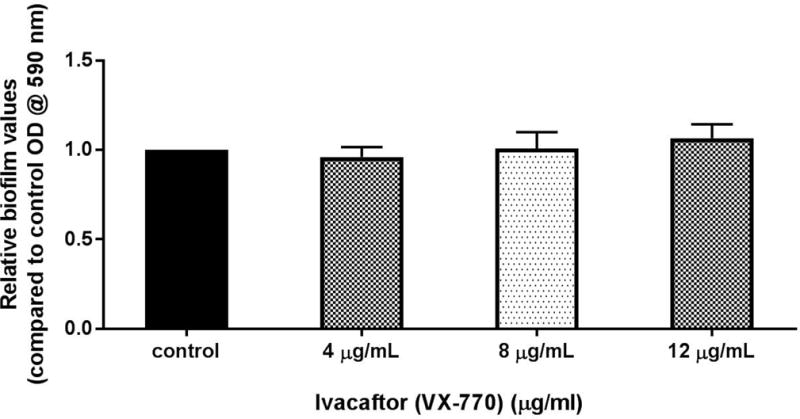

Anti-biofilm activity of ivacaftor was evaluated with escalating concentrations 4, 8, and 12 μg/ml. These doses were selected based on our previous experiments (unpublished) to avoid dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)’s antibacterial effect. DMSO vehicle controls reduced PAO-1 concentrations with escalating doses above 16 μg/ml. As expected, there was no dose-dependent inhibition of biofilm mass at the 3 selected concentrations of ivacaftor in the current study (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of ivacaftor on PAO-1 biofilm formation.

There was no observable effect on biofilm biomass with any ivacaftor concentration tested.

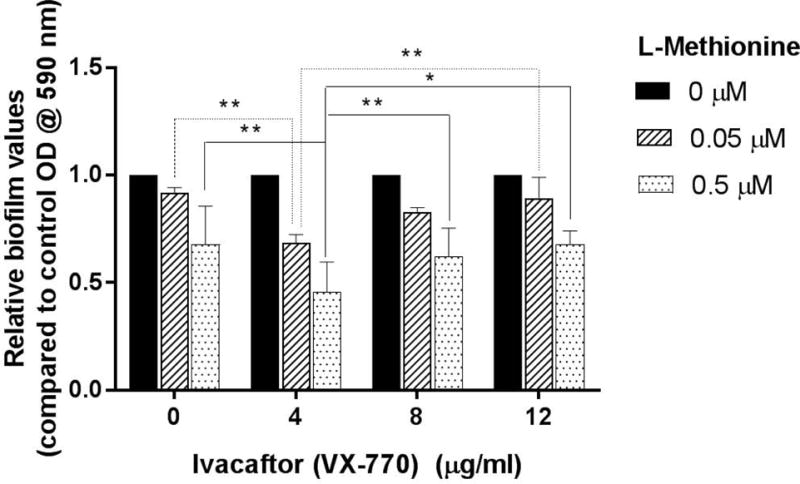

Synergistic effect on PAO-1 biofilm formation by L-methionine and ivacaftor

PAO-1 biofilms were grown in the presence of the 2 chosen L-methionine concentrations (0.05 μM, 0.5 μM) combined with the concentrations of ivacaftor used in the previous experiments (Figure 3). L-methionine at 0.05 μM showed significant reduction in biofilm mass when combined with ivacaftor at all concentrations vs. L-methionine alone. Interestingly, the greatest decrease was observed with the lowest ivacaftor concentration [4 μg/ml ivacaftor = 31.5 ± 3.8 % reduction (n = 4, p < 0.001), 8 μg/ml ivacaftor = 17.2 ± 2.2 % reduction (n = 4, p < 0.001), 12 μg/ml ivacaftor = 10.7 ± 9.7 % reduction (n = 4, p < 0.05)].

Figure 3. Enhanced anti-biofilm formation activity of L-methionine against P. aeruginosa PAO-1 with ivacaftor.

L-methionine anti-biofilm activity was detected at all concentrations ivacaftor.

* represents a statistical significance of p<0.05. ** represents a statistical significance of p<0.01. Significance was measured using a two-way ANOVA test with a Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons test. All conditions consisted of at least 4 experiments.

When combining ivacaftor with 0.5 μM L-methionine, a similar pattern was observed. All concentrations of ivacaftor significantly inhibited relative biofilm biomass with the lowest concentration providing the greatest decline [4 μg/ml ivacaftor = 54.5 ± 14.1 % reduction (n=4, p<0.001), 8 μg/mL ivacaftor = 37.9 ± 13.2 % reduction (n=4, p<0.001), 12 μg/ml ivacaftor = 32.3 ± 6.3 % reduction (n=4, p<0.001)]. Synergistic anti-biofilm effect of L-methionine and ivacaftor was noticed at 0.05 μM and 0.5 μM of L-methionine with 4 μg/ml of ivacaftor (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.0415).

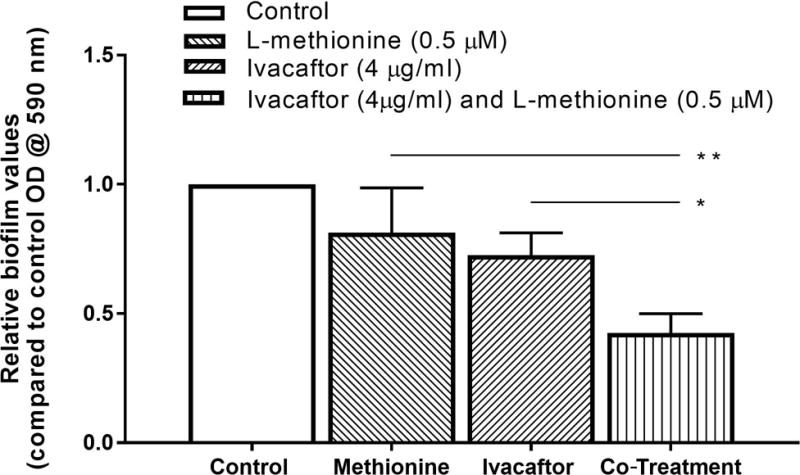

Eradication of PAO-1 biofilm by L-methionine and ivacaftor

The capability of 0.5 μM of L-methionine plus 4 μg/ml of ivacaftor to eradicate pre-existing PAO-1 biofilms was evaluated. Drugs were administered 72 hours after PAO-1 incubation. Combining L-methionine with ivacaftor significantly decreased biofilm mass (co-treatment (0.5 μM of L-methionine + 4 μg/ml ivacaftor) = 57.5 ± 0.07 % eradication (n = 6), p = 0.043) compared to either agent alone (0.5 μM of L-methionine = 18.7% ± 0.17 % eradication, 4 μg/ml ivacaftor = 27.4% ± 0.09 % eradication) (Figure 4). There was no statistically significant difference in eradication of biofilm mass by single agent compared to control (p > 0.05).

Figure 4. Enhanced anti-biofilm eradication activity of L-methionine against P. aeruginosa PAO-1 with ivacaftor.

* represents a statistical significance of p<0.05. ** represents a statistical significance of p<0.01. Significance was measured using one-way ANOVA test with a Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons test. All conditions consisted of at least 4 experiments.

Agar Diffusion Tests

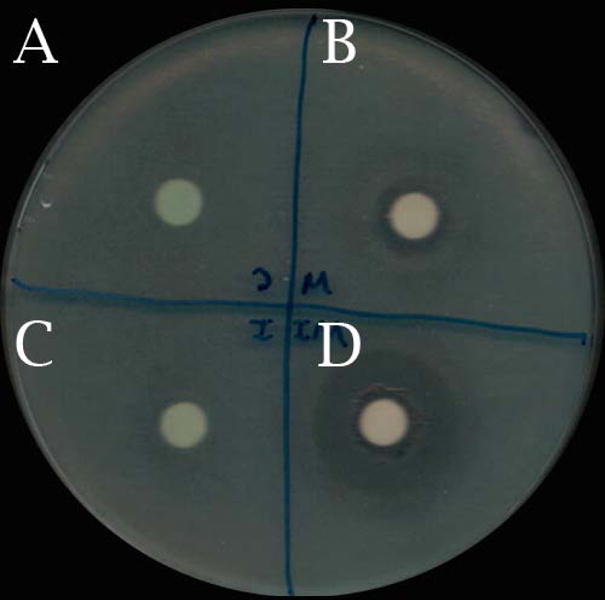

To evaluate the synergy of L-methionine and ivacaftor against planktonic growth of PAO-1, blank diffusion disks were impregnated with pure LB broth, 0.5 μM L-methionine, 4 μM ivacaftor, or ivacaftor (4 μg/mL) + L-methionine (0.5 μM). Disks (n = 4, per condition) were inserted onto evenly streaked plates of MH agar and incubated for 24 hours. The radii of the clear zones around the disks were measured with ImageJ (Figure 5). An increase in the susceptibility of PAO-1 was observed from single to combined drug concentrations (clear zone radius (cm), control = 0 ± 0.00, ivacaftor = 0.28 ± 0.16, L-methionine = 0.59 ± 0.12, L-methionine + ivacaftor = 0.92 ± 0.05, p < 0.05). The mean radius of the clear zone of ciprofloxacin (2μg) was 1.16 +/− 0.01 cm and there was no statistical difference between ciprofloxacin and L-methionine + ivacaftor.

Figure 5. Representative image of agar susceptibility test for 18 hours.

A: Control

B: L-methionine 0.5 μM

C: Ivacaftor 4 μg/mL

D: L-methionine 0.5 μM and ivacaftor 4 μg/mL

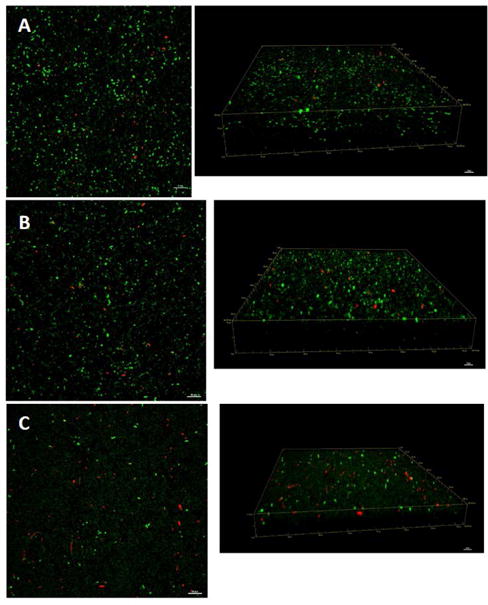

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

Total biofilm area and bacterial viability were calculated in the presence of L-methionine (0.5 μM) or L-methionine with ivacaftor (4 μg/mL) for 3 days under static biofilm conditions (Figure 6). Image analysis using bioImage_L revealed the biofilm area was significantly smaller with L-methionine (3.3 ± 0.45%) compared to controls (19.1 ± 0.85%, p < 0.001), but adding ivacaftor reduced the biofilm area to 1.2 ± 0.19%. This was significantly reduced compared to L-methionine alone (n = 12 each, p < 0.001). When we calculated the thickness of the biomass, there were significant differences among groups (controls = 21.6 ± 1.3 μm: L-methionine = 11.1 ± 0.6 μm: L-methionine + ivacaftor = 6.8 ± 1.4 μm, p < 0.0001).

Figure 6. Representative confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO-1 biofilms with 3D structures by CLSM z-stacks.

A: Control

B: L-methionine 0.5 μM

C: L-methionine 0.5 μM plus ivacaftor 4 μg/ml

Green - live cells, Red - dead cells. Scale bars indicate 20 μM.

DISCUSSION

Bacteria adhered to a surface form the complicated structural architecture of a biofilm, endowing resistance against antibacterial therapy. Bacterial biofilms are a conducive environment where bacterial cells can perceive antibiotics, communicate with each other, and change gene and metabolic activity to create less susceptibility to antibiotics.25,26 Biofilms are linked to the onset of recalcitrant CRS, and have substantial impact to the clinical course of the disease due to induction of strong antibiotic resistance.27-29 New medical therapies directed towards biofilm formation are clearly required to treat recalcitrant CRS infections. In the current study, a synergistic effect against anti-biofilm formation was noted with low concentrations of L-methionine (0.5 μM) and ivacaftor (4 μg/ml) without the addition of traditional antibiotics. A strategy using topical delivery of L-methionine and ivacaftor to the sinuses as therapy for recalcitrant biofilm-forming P. aeruginosa infections would help avoid expansion and promotion of resistant strains of bacteria and assist with clearance of biofilm forming niduses that inevitably result in acute exacerbations.6

L-methionine is an amino acid not directly associated with antibacterial therapy, but was recently shown to inhibit and disassemble Pseudomonas biofilms at low concentrations (0.5 μM). The mechanism is thought to be related to induction of bacterial DNase expression which then degrades extracellular DNA within the biofilm.13 However, the mechanism behind DNase induction is not fully understood. Since L-methionine is an amino acid and can be utilized by bacteria as a nutrient source, higher concentrations may not provide the specific cue to induce DNase. At significantly low concentrations, bacteria may not be capable of detecting L-methionine as a signal for the cue.13 The biofilm inhibitory effect observed at lower concentrations of L-methionine may also be linked to quorum sensing – a mechanism highly sensitive to signaling molecules.13,30 Notably, DNase treatments have been exploited to improve infections in the lower and upper airways of cystic fibrosis patients. The mucolytic, dornase alfa, once daily (2.5 mg) administered intranasally was found to be improve sinusitis symptoms in cystic fibrosis patient in several clinical trials.15,31-36

Ivacaftor enhances Cl− secretion in airway epithelia, including the sinonasal mucosa through CFTR ion channels.14-17 Past studies have reported off target anti-bacterial effects of ivacaftor as having an MIC against P. aeruginosa above 32 μg/ml.19 Indeed, the lower concentrations (4, 8 and 12 μg/ml) used in the present study did not have an effect on biofilm formation unless combined with L-methionine indicating a synergistic effect. A low concentration of ivacaftor (e.g. 4 μg/ml) significantly enhanced the activity of L-methionine at 0.5 μM, suggesting that this drug combination holds promise as a treatment for P. aeruginosa biofilm formation associated with CRS.

While the reasons for this phenomenon are currently unknown, biofilm disassembly by L-methionine through DNase induction could provide access to resident bacteria for the antimicrobial effects of ivacaftor. Previous studies indicate that the outer membrane of P. aeruginosa limits the diffusion of hydrophobic substances, including antibiotics.19 Therefore, we hypothesized that the outer membrane of P. aeruginosa might serve as a barrier for ivacaftor penetration, which may require dissolution by L-methionine (DNase) first. To test this hypothesis, L-methionine (0.5 μM) was administered, followed by L-methionine 48 hours later. However, we did not observe a dose-dependent reduction in biomass with ivacaftor at 0.5 μM L-methionine (Supplement Figure 1). The highest inhibition was still observed at the lower dose of ivacaftor (4 and 8 μg/ml). Although the MIC of ivacaftor has been reported above 32 μg/ml,19 we were unable to dissolve ivacaftor into regular LB broth without the addition of higher concentrations of DMSO, which would affect the behavior of the PAO1 strain. It is important to note that the agar diffusion test clearly shows that both L-methionine and ivacaftor have activity against planktonic PAO1 bacteria indicating other undescribed mechanisms may be involved.

Methionine is an indispensable amino acid and must be supplied from the diet. Long term human studies did not demonstrate serious toxicity, except at very high levels of intake.37 Despite the function of methionine as a precursor of homocysteine, and the role of homocysteine in vascular damage and cardiovascular disease, there is no evidence that dietary intake of methionine within reasonable limits will cause cardiovascular damage. A single dose of 100 mg/kg body weight has been shown to be safe, but this is about 7 times the daily requirement for sulfur amino acids. In infants, methionine intakes of 2–5 times normal resulted in impaired growth and extremely high plasma methionine levels, but no adverse long-term consequences were observed.37,38

There are several limitations to this study. P. aeruginosa is known for its intrinsic resistance to a variety of antimicrobial agents and toxic compounds, but only the PAO1 strain was tested.39 In addition, DNase activity was not measured in the supernatants of the cell cultures, which may have provided clues to the underlying pathophysiology at each setting. Finally, these in vitro experiments only demonstrated the inhibitory effect of biofilm formation rather than disruption of previously existing biofilms. Further studies are planned to 1) test activity against multi-drug resistant strains of P. aeruginosa from human isolates, 2) evaluate the underlying mechanism of action, including generation of DNase, 3) administer to a co-cultured model of PAO1 on nasal epithelial cell culture,29 and 4) validate the efficacy of L-methionine/ivacaftor topical therapy in a rabbit model of P. aeruginosa sinusitis.

CONCLUSION

Ivacaftor enhanced L-methionine’s anti-biofilm activity against the PAO-1 strain of P. aeruginosa. This combination therapy represents an exciting treatment strategy for recalcitrant biofilm-associated sinus infections. Translations of these findings to preclinical and clinical trials are planned.

Supplementary Material

L-methionine was given first then followed by ivacaftor in 48 hours. The highest anti-biofilm activity was detected at the lower concentrations of ivacaftor (4 and 8 μg/ml). NS: no statistical significance. * represents a statistical significance of p<0.05. ** represents a statistical significance of p<0.01. Significance was measured using one-way ANOVA test. All conditions consisted of at least 4 experiments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1 R01 HL133006-02) and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (5P30DK072482-04, CF Research Center Pilot Award) to B.A.W. and John W. Kirklin Research and Education Foundation Fellowship Award, UAB Faculty Development Research Award, American Rhinologic Society New Investigator Award, and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Research Development Pilot grant (ROWE15R0) to D.Y.C,.

Do-Yeon Cho, MD receives research grant support from Bionorica Inc.

Bradford A. Woodworth, M.D. is a consultant for Olympus and Cook Medical. He also receives grant support from Cook Medical and Bionorica Inc.

Footnotes

Manuscript will be presented at the American Rhinologic Society Meetings, Chicago, IL, Sep 9th, 2017.

References

- 1.Orlandi RR, Kingdom TT, Hwang PH, et al. International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6(Suppl 1):S22–209. doi: 10.1002/alr.21695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendouah Z, Barbeau J, Hamad WA, Desrosiers M. Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is associated with an unfavorable evolution after surgery for chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendouah Z, Barbeau J, Hamad WA, Desrosiers M. Use of an in vitro assay for determination of biofilm-forming capacity of bacteria in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:434–438. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2006.20.2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Psaltis AJ, Weitzel EK, Ha KR, Wormald PJ. The effect of bacterial biofilms on post-sinus surgical outcomes. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:1–6. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Psaltis AJ, Wormald PJ, Ha KR, Tan LW. Reduced levels of lactoferrin in biofilm-associated chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:895–901. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31816381d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy JL, Borish L. Chronic rhinosinusitis and antibiotics: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27:467–472. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu AG, Antunes MB, Palmer JN, Cohen NA. Evaluation of the in vivo efficacy of topical tobramycin against Pseudomonas sinonasal biofilms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:1130–1134. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saginur R, Stdenis M, Ferris W, et al. Multiple combination bactericidal testing of staphylococcal biofilms from implant-associated infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:55–61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.55-61.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slinger R, Chan F, Ferris W, et al. Multiple combination antibiotic susceptibility testing of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae biofilms. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;56:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolodkin-Gal I, Romero D, Cao S, Clardy J, Kolter R, Losick R. D-amino acids trigger biofilm disassembly. Science. 2010;328:627–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1188628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandenburg KS, Rodriguez KJ, McAnulty JF, et al. Tryptophan inhibits biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1921–1925. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00007-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gnanadhas DP, Elango M, Janardhanraj S, et al. Successful treatment of biofilm infections using shock waves combined with antibiotic therapy. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17440. doi: 10.1038/srep17440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gnanadhas DP, Elango M, Datey A, Chakravortty D. Chronic lung infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm is cured by L-Methionine in combination with antibiotic therapy. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16043. doi: 10.1038/srep16043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaaban MR, Kejner A, Rowe SM, Woodworth BA. Cystic fibrosis chronic rhinosinusitis: a comprehensive review. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2013;27:387–395. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Illing EA, Woodworth BA. Management of the upper airway in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20:623–631. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowe SM, Liu B, Hill A, et al. Optimizing nasal potential difference analysis for CFTR modulator development: assessment of ivacaftor in CF subjects with the G551D-CFTR mutation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang S, Blount AC, McNicholas CM, et al. Resveratrol enhances airway surface liquid depth in sinonasal epithelium by increasing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator open probability. PloS one. 2013;8:e81589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conger BT, Zhang S, Skinner D, et al. Comparison of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and ciliary beat frequency activation by the CFTR Modulators Genistein, VRT-532, and UCCF-152 in primary sinonasal epithelial cultures. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:822–827. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reznikov LR, Abou Alaiwa MH, Dohrn CL, et al. Antibacterial properties of the CFTR potentiator ivacaftor. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13:515–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider EK, Azad MA, Han ML, et al. An “Unlikely” Pair: The Antimicrobial Synergy of Polymyxin B in Combination with the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Drugs KALYDECO and ORKAMBI. ACS Infect Dis. 2016;2:478–488. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moskowitz SM, Foster JM, Emerson J, Burns JL. Clinically feasible biofilm susceptibility assay for isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1915–1922. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.1915-1922.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merritt JH, Kadouri DE, O’Toole GA. Growing and analyzing static biofilms. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b01s00. Chapter 1:Unit 1B 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins TJ. ImageJ for microscopy. Biotechniques. 2007;43:25–30. doi: 10.2144/000112517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chavez de Paz LE. Image analysis software based on color segmentation for characterization of viability and physiological activity of biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1734–1739. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02000-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh R, Ray P, Das A, Sharma M. Penetration of antibiotics through Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1955–1958. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Molin S, Ciofu O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2010;35:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perloff JR, Palmer JN. Evidence of bacterial biofilms on frontal recess stents in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18:377–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramakrishnan Y, Shields RC, Elbadawey MR, Wilson JA. Biofilms in chronic rhinosinusitis: what is new and where next? J Laryngol Otol. 2015;129:744–751. doi: 10.1017/S0022215115001620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodworth BA, Tamashiro E, Bhargave G, Cohen NA, Palmer JN. An in vitro model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on viable airway epithelial cell monolayers. American journal of rhinology. 2008;22:235–238. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alhede M, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Alhede M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: mechanisms of immune evasion. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2014;86:1–40. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800262-9.00001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cimmino M, Nardone M, Cavaliere M, et al. Dornase alfa as postoperative therapy in cystic fibrosis sinonasal disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:1097–1101. doi: 10.1001/archotol.131.12.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tetz GV, Artemenko NK, Tetz VV. Effect of DNase and antibiotics on biofilm characteristics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1204–1209. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00471-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virgin FW, Rowe SM, Wade MB, et al. Extensive surgical and comprehensive postoperative medical management for cystic fibrosis chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:70–75. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho DY, Skinner D, Zhang S, et al. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activation by the solvent ethanol: implications for topical drug delivery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:178–184. doi: 10.1002/alr.21638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho DY, Woodworth BA. Acquired Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Deficiency. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;79:78–85. doi: 10.1159/000445134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mainz JG, Schien C, Schiller I, et al. Sinonasal inhalation of dornase alfa administered by vibrating aerosol to cystic fibrosis patients: a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over trial. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garlick PJ. Toxicity of methionine in humans. J Nutr. 2006;136:1722S–1725S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1722S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harvey Mudd S, Braverman N, Pomper M. Infantile hypermethioninemia and hyperhomocysteinemia due to high methionine intake: a diagnostic trap. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;79:6–16. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(03)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolter DJ, Black JA, Lister PD, Hanson ND. Multiple genotypic changes in hypersusceptible strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients do not always correlate with the phenotype. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:294–300. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

L-methionine was given first then followed by ivacaftor in 48 hours. The highest anti-biofilm activity was detected at the lower concentrations of ivacaftor (4 and 8 μg/ml). NS: no statistical significance. * represents a statistical significance of p<0.05. ** represents a statistical significance of p<0.01. Significance was measured using one-way ANOVA test. All conditions consisted of at least 4 experiments.