Abstract

Background

Accurate estimates of the burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are needed to establish the magnitude of this global threat in terms of both health and cost, and to paramaterise cost-effectiveness evaluations of interventions aiming to tackle the problem. This review aimed to establish the alternative methodologies used in estimating AMR burden in order to appraise the current evidence base.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, EconLit, PubMed and grey literature were searched. English language studies evaluating the impact of AMR (from any microbe) on patient, payer/provider and economic burden published between January 2013 and December 2015 were included. Independent screening of title/abstracts followed by full texts was performed using pre-specified criteria. A study quality score (from zero to one) was derived using Newcastle-Ottawa and Philips checklists. Extracted study data were used to compare study method and resulting burden estimate, according to perspective. Monetary costs were converted into 2013 USD.

Results

Out of 5187 unique retrievals, 214 studies were included. One hundred eighty-seven studies estimated patient health, 75 studies estimated payer/provider and 11 studies estimated economic burden. 64% of included studies were single centre. The majority of studies estimating patient or provider/payer burden used regression techniques. 48% of studies estimating mortality burden found a significant impact from resistance, excess healthcare system costs ranged from non-significance to $1 billion per year, whilst economic burden ranged from $21,832 per case to over $3 trillion in GDP loss. Median quality scores (interquartile range) for patient, payer/provider and economic burden studies were 0.67 (0.56-0.67), 0.56 (0.46-0.67) and 0.53 (0.44-0.60) respectively.

Conclusions

This study highlights what methodological assumptions and biases can occur dependent on chosen outcome and perspective. Currently, there is considerable variability in burden estimates, which can lead in-turn to inaccurate intervention evaluations and poor policy/investment decisions. Future research should utilise the recommendations presented in this review.

Trial registration

This systematic review is registered with PROSPERO (PROSPERO CRD42016037510).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13756-018-0336-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Antibiotic resistance, Burden, Cost

Background

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a cause for global concern due to the current and potential impact on global population health, costs to healthcare systems and Gross Domestic Product (GDP), mainly through reduced treatment options [1]. Recent reports suggest that absolute numbers of infections due to resistant microbes are increasing globally [2–4]. Estimates of the potential economic burden of AMR from recent reports, such as ‘The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance’ [1], are being utilised by policy makers to push AMR up the political agenda [5]. However, more precise estimates of AMR burden are needed to inform policy through health economic models evaluating interventions attempting to prevent, treat or stop the spread of resistant infections [6, 7].

In order to establish burden, the perspective being taken should be defined. The patient perspective refers to associated mortality and morbidity (including clinical outcomes), while the payer perspective can include attributable costs to the payers of healthcare including insurers or national payers [6]. The provider perspective estimates the burden to certain providers of healthcare, such as hospitals and primary care practices [6]. In cases where there is national/governmental provision and payment of healthcare services, the provider and payer perspectives may align to be the same, such as in the case of the National Health Service and the Department of Health in England [6]. The economic (or societal) perspective generally includes the potential impact on the labour force through lost productivity [8, 9], but can also include the burden on carers and patient out-of-pocket expenses [10, 11]. AMR may also create burden through secondary effects, referred to in this review as secondary burden. Secondary patient burden, and onward effects to healthcare system or society, occurs when procedures that utilise antimicrobials to reduce the risk of post-intervention adverse events (such as surgical procedures utilising prophylactic antibiotics) are performed less frequently due to AMR increasing the risk of adverse events [12].

The different perspectives of burden produce varying outcome measures. For example, from a patient perspective an excess mortality figure may be determined [13], whilst looking from a payer or provider perspective could produce an excess cost of hospital treatment in monetary terms [14], and economic burden could refer to excess GDP losses for a country [15]. Obtaining estimates for these different outcomes, may require different methodologies, ranging from case-control studies with regression analyses to complex mathematical and economic models [16, 17].

Past descriptive review articles have discussed the methods of estimating the burden of AMR [9, 18, 19]. However, since an update in 2012 of a previous systematic review [8, 20], there has been no formal systematic assessment of the methods used in AMR burden estimation, or the variation in resulting outcomes. The 2012 update concluded economic evidence was lacking, and that over the 21 studies included there were large variations in the estimates of AMR burden [8]. However, there been no formal quality assessment of recent AMR burden evidence across the stated perspectives, which is needed when discussing study methodology and its limitations. Given the growing media coverage of and policy interest in AMR over recent years [21, 22], there has been a corresponding marked increase in the published evidence on AMR impact. As such, this review aimed to capture and assess this recent portion of the literature, by reviewing the evidence published since the review in 2012 by Smith and Coast [8]. This review aimed to capture both the burden in the sense of the incremental impact of resistance (in addition to infection) and the burden of resistant infections among all of the population. Therefore this systematic review aimed to address the following research questions in regards to the human population, with no limitation on microbe of interest; (i) what perspectives and resulting methodologies have been used to estimate AMR burden in the recent published literature? (ii) Do AMR burden estimates differ by perspective and methodology? (iii) What is the quality of this recent evidence on the burden of AMR?

Methods

This Systematic review is in line with PRISMA guidance, is registered with PROSPERO (registration number PROSPERO CRD42016037510) and has a previously published protocol [23–25].

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

Studies which aimed to quantify the burden of AMR (in humans) published since the Smith and Coast review in 2012 [8] were of interest, and as such, the search was limited from January 2013 – December 2015. Ovid ‘Medline & EMBASE’, Scopus and EconLit were searched utilising a search string, which employed combinations of the following terms; excess, associated, attributable, burden, morbidity, mortality, cost, economic, clinical, global, impact, outcome, burden, antibiotic, antimicrobial, multi-drug, microbial-drug, resistan*, gram-positive, gram-negative, susceptib*,nonsusceptib*, enterococc*, Escherichia, streptococc*, staphylococc*, klebsiealla, pseudomonas, neisseria, chlamydia, clostridi*, mycobacteri*. In deviation to the published protocol [25], an additional search of PubMed was conducted for literature published within the stated time period, whereby titles were searched using the following string; “(((((mortality[Title]) OR cost[Title]) OR length of stay[Title]) OR productivity[Title]) AND resistant[Title]) AND infection*[Title]” [26]. The following websites were also searched for grey literature: Public Health England, Public Health Wales, Health Protection Scotland, NHS Health Scotland, Department of Health (UK), Health Protection Agency, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organisation, European Commission for Public Health, Review on Antimicrobial Resistance.

The modified PICO inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 1) were utilised to screen title/abstracts and subsequently full-texts [27].

Table 1.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria Applied [25]

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Humans | Animals only |

| All ages | Plants only | |

| All sexes | ||

| Infection with antimicrobial resistant organism (or similar such as Extended Spectrum Beta-lactamase producing organisms). This includes future predictions of related infected populations, such as in the case of a “post-antibiotic” era | ||

| Outcomes | Associated health burden, including mortality and morbidity | Health-Related Quality of Life only |

| Associated healthcare cost burden, including resource use and opportunity cost | Molecular biology only | |

| Economic burden, including loss of productivity | Epidemiology only | |

| Burden from not being able to use antibiotics in ways previously or currently used in healthcare, including reduced surgery or chemotherapy | Outcomes associated with the evaluation of an intervention only | |

| Study design | Case–control studies | Editorials |

| Cohort studies | Letters | |

| Cross–sectional studies | Case series reports | |

| Longitudinal studies | Conference reports | |

| Randomised controlled trials | Evaluations of interventions | |

| Modelling studies | Reviews | |

| Economic Evaluations |

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted from each study into a Data Extraction Table using Microsoft Excel. The following variables were collected as part of this process; study identifier, perspective, infection of interest (exposure, non-exposure, case and control definitions), outcome, country setting, study population, study design, data setting, epidemiological scope, method, sample size, (resistance-related) result, stated limitations and quality (risk of bias).

To establish what perspectives and resulting methodologies have been used in establishing AMR burden, study perspectives were grouped into either patient, healthcare system (representing payer and/or provider perspectives) or economic/societal burden. Studies estimating the secondary effects of AMR can do so by estimating the potential impact on health (such as excess deaths), healthcare system or economic burden (excess cost), so could be marked under each of these perspectives. Study methodologies were grouped into the following categories; regression analysis (parametric regression models), survival analysis (this included semi-parametric Cox proportional hazard models and non-parametric time to event analysis), matching, multistate models (including decision trees), economic models (including total factor or computable general equilibrium models), stepwise calculations (for example synthesising evidence from the literature and applying simple calculations to arrive at an estimate), significance tests and other (if none of the former categories applied).

The outcome of particular interest for patient burden was mortality, using odds ratio (OR) and hazard ratio (HR) measures. In this review, length of stay (LoS), alongside monetary cost, was recorded as a healthcare system burden outcome, as it has been shown that for healthcare associated infections LoS is a major contributing factor to hospital costs [28]. For economic burden, monetary cost was considered the main outcome of interest, however reporting of productivity, GDP and other such economic measures were also recorded. Impact significance was defined by p values (less than 0.05) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), where appropriate.

Risk of bias within individual studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scales for cohort and case-control studies [29]. For this review a case-control study was defined when outcomes of interest (such death) were used to select the case and control groups, whereas cohort studies selected cases based on exposure to resistance [30]. The Newcastle-Ottawa checklists include four domains of quality and eight possible stars [29]. The Philips checklist was used for modelling studies, which includes three domains of quality and 57 possible stars [31]. A quality score was derived as the proportion of applicable checklist stars achieved (zero and one representing no checklist items achieved and all checklist items achieved respectively), please see Additional file 1: Tables S1, S2 and S3 for the full checklists utilised.

Risk of bias across the evidence was presented using the median and interquartile ranges of the quality score by perspective. This was a deviation in methodology from the published protocol, which proposed evaluating sign and significance of results [25], and was chosen as any other summary figures would be flawed due to the high heterogeneity in infection of interest and outcome [32].

Data analysis

Due to study heterogeneity no meta-analyses were performed. Monetary costs found were converted into 2013 United States dollars (USD) by inflating the cost to 2013 original-currency estimates using annual inflation rates [33, 34], then converting this into USD utilising 2013 average exchange rates [35].

Descriptive statistics (such as proportions of papers and average quality scores), tables and graphs to collate and present ORs, HRs, LoS and monetary cost were executed in Microsoft Excel and R version 3.3.2 using packages ‘plyr’, ‘metafor’ and ‘ggplot2’ [36–38].

Results

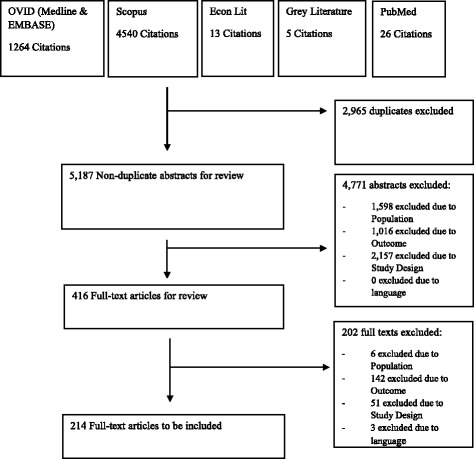

A total of 5187 unique titles and abstracts were retrieved over the specified search period. Applying the selection process resulted in a total of 214 studies being included in the final review (Fig. 1). One hundred eighty-seven studies included a patient burden measure, 75 a healthcare system burden measure, and only 11 studies included an economic burden measure (Table 2). The most individually studied genus was Staphylococcus (23%, 50/214), followed by Klebsiella (9%, 19/214) and Acinetobacter (8%, 18/214) respectively. The countries which individually produced the highest number of studies were the USA (19%, 40/214), followed by South Korea (7%, 15/214) and Spain (6%, 13/214). 64% of studies (138/214) used data from just one centre. The majority of studies (89%, 190/214) did not specify the epidemiological scope in estimating AMR burden, for example by stating whether relevant included infections were due to endemic- or outbreak-related microbes. See Additional file 1: Table S4 for individual study details.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Diagram of Article Retrieval & Inclusion

Table 2.

Perspectives & Methods used to Estimate the Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance

| Patient % (n = 187) | Healthcare System % (n = 75) | Economic % (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Analysis | 44.9% | 34.7% | 9.1% |

| Survival Analysis | 20.9% | 9.3% | 0.0% |

| Matching | 4.8% | 10.7% | 9.1% |

| Multistate model | 2.1% | 6.7% | 27.3% |

| Economic Model | 0.0% | 0.0% | 18.2% |

| Significance Tests | 26.2% | 32.0% | 0.0% |

| Stepwise calculation | 1.1% | 6.7% | 27.3% |

| Qualitative | 0.0% | 0.0% | 9.1% |

Note that some studies included more than one burden perspective per study (for example a study reporting impact on mortality and costs would appear in multiple perspective categories)

Estimating the patient burden of AMR

For estimating the patient burden of AMR, regression analyses and significance tests were the most utilised methods (Table 2). 95% (177/187) of studies estimating patient burden calculated mortality burden, with the remaining 5% (10/187) focusing on morbidity burden. Of those estimating a mortality burden, 48% (85/177) of studies found that AMR had a significant impact on mortality. Studies which aimed to estimate the impact of resistance on morbidity mainly focused on clinical outcomes such as clinical failure, time to stability, recurring infections or development of secondary infections [39–47].

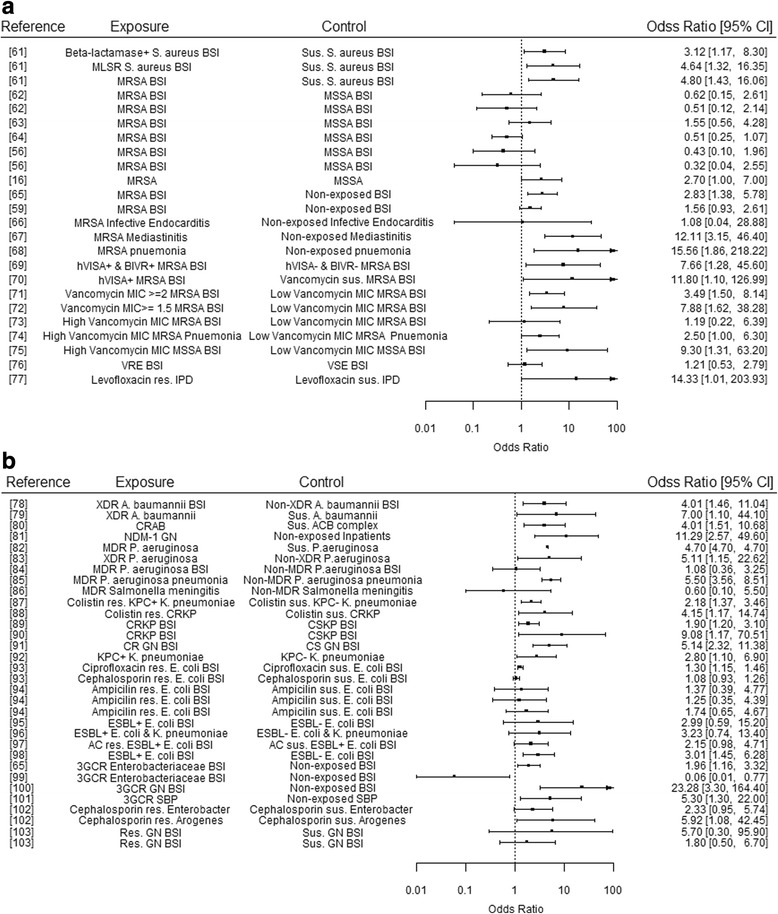

The majority of studies that utilised standard regression techniques to estimate ORs of a mortality event found resistance to be associated with higher mortality (Fig. 2a and Fig. 2b). Focusing on those which directly compared resistant and susceptible infections explicitly, 50% (7/14) and 47% (9/19) of the studies for Gram-positive and Gram-negative exposures, respectively, had 95% confidence intervals which crossed this OR = 1 threshold. This suggests non-statistical significance of such results. Across Gram-positive and Gram-negative infections, this occurred in 4/15 studies investigating resistant cases against “non-exposed” controls and in 2/8 studies investigating the burden of additional resistance mechanisms on already resistant infections (for example the impact of vancomycin resistance on Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) patients).

Fig. 2.

Odds ratios of Mortality Outcomes for Resistant Infections. Results presented are from studies utilising regression techniques, where 1.0 represents the point at which exposure does not affect the odds of the outcome occurring. The box point represents the reported OR value, with horizontal lines representing the reported 95% Confidence Interval. Results have not been adjusted or adapted to represent sample size, and are presented grouped by genera. a Gram-positive Bacteria. b Gram-negative Bacteria. [16, 56, 59, 61–103]

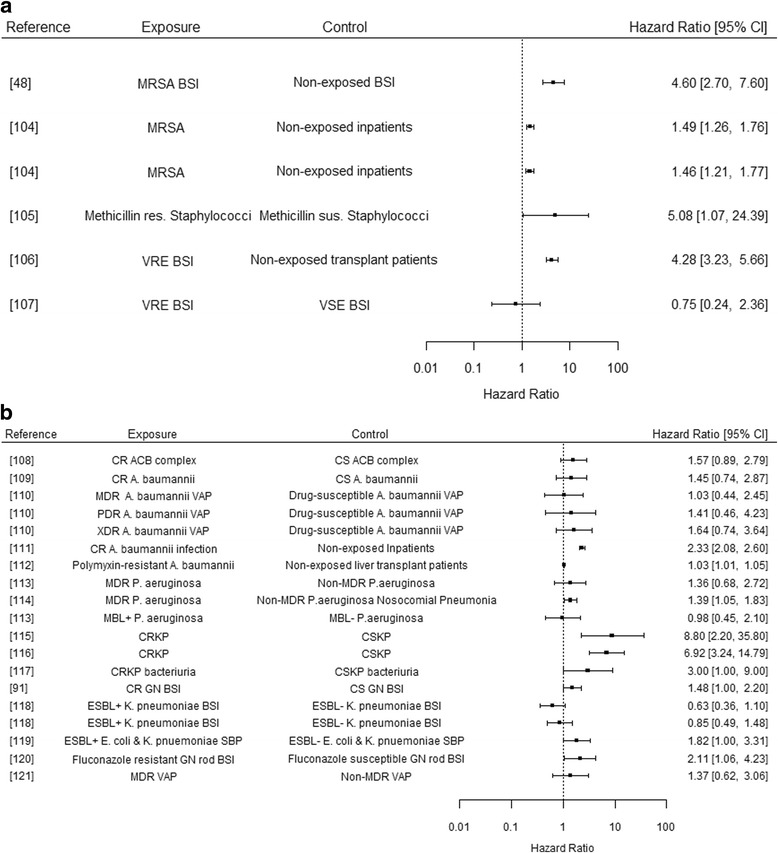

Comparing Figs. 2 and 3 would suggest there is no clear consensus from either method (parametric regression or Cox proportional hazards regression) as to whether there is a significant impact of bacterial resistance mechanisms on mortality outcomes, though it should be noted that different measures of mortality have been used across these studies (see Additional file 1: Table S4). 32% (8/25) of these studies estimating mortality-related hazard ratios, did so in relation to in-hospital mortality. Such analysis may not accurately estimate the impact of exposure (versus non-exposure) on outcome, due to the failure of the non-informative censoring assumption, as the cause of being discharged may be related to the likelihood of experiencing death. As the infection type, resistance type and outcomes are different across the aforementioned studies a rigorous comparison cannot be made.

Fig. 3.

Hazard Ratios of Mortality Outcomes for Resistant Infections. Results presented are from studies utilising Cox proportional hazards regression techniques, where 1.0 represents the point at which exposure and control experience the same event rate at any point in time. The box point represents the reported HR value, with horizontal lines representing the reported 95% Confidence Interval. Results have not been adjusted or adapted to represent sample size, and are presented grouped by genera. a Gram-positive Bacteria. b Gram-negative Bacteria. [48, 91, 104–121]

Only one study estimated the potential patient burden of AMR via secondary effects (secondary patient burden), by evaluating the impact on mortality (excess deaths) of reduced prophylactic antibiotic efficacy in the United States [12]. Utilising an evidence synthesis and stepwise calculation approach, this study estimated that a 30% reduction in the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis for certain surgical and chemotherapeutic procedures would result in 6300 infection-related deaths annually [12].

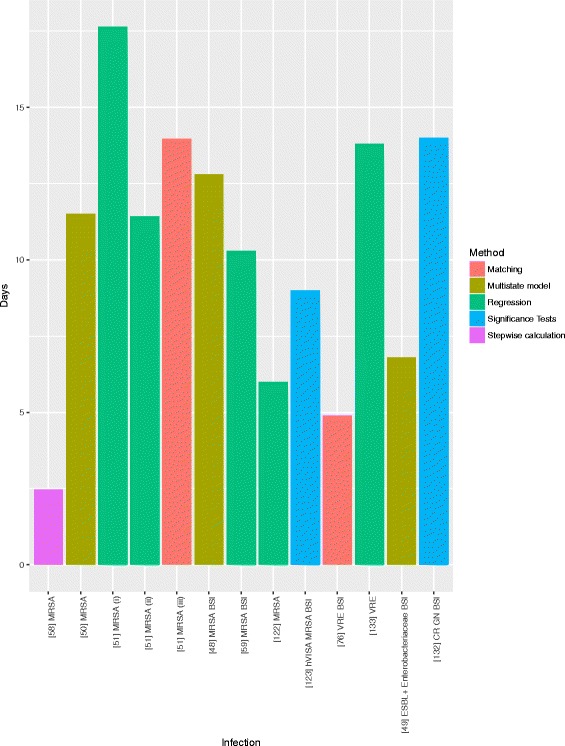

Estimating the healthcare system burden of AMR

For estimating the healthcare system burden (which incorporates the payer and provider perspectives) of AMR, regression analyses and significance tests were the most utilised methods. Seventy-five studies estimated healthcare system burden, 64 of these estimated LoS burden due to AMR and 31 estimated monetary cost (with some studies estimating both). The majority of studies evaluating LoS (69%, 44/64) found that resistance had a statistically significant impact, however 39% (17/44) of these utilised significance testing against descriptive statistics (such as median length of stay). Thirteen studies estimated excess LoS due to resistant infections (Fig. 4), with 3 studies using a multistate modelling methodology to estimate LoS. Multistate models attempt to adjust for time dependency bias [48–50], however this bias has also been adjusted for in other ways, such as shifting forward the index date from the date of hospital admission to the first day of the second calendar month of the patient’s stay [51]. The majority of excess LoS estimates were for Gram-positive bacteria, with only two estimates for a Gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 4). Excess LoS was estimated at 12.8 days for MRSA bloodstream infections [95% CI 6.2 - 26.1 days] [48] in Australia, 11.5 [95% CI: 7.9-15] days for MRSA in Switzerland [49] and 11.43 [95% CI; 10.44 – 12.43] days for MRSA in American Veterans, utilising time dependency adjusted methods described above [50]. These are similar to those computed by regression but much higher than that estimated by stepwise calculations (Fig. 4), though all are from different populations.

Fig. 4.

Estimates of Excess Length of Stay of Hospital/ICU Stay Caused by Antimicrobial Resistance. (i) - (iii) denote different methods used in a single study [48–51, 58, 59, 76, 122, 123, 132 ,133]

A variety of methods have been used to calculate healthcare system monetary costs, with no clear majority of one method seen (Table 3). After conversion to 2013 USD for comparing excess/attributable costs, for Extended-Spectrum beta-Lactamase (ESBL) in bloodstream infections, a matching study found no significant impact on healthcare system costs [52], whilst a multistate model found an associated $10,154 loss per case [49]. For MRSA estimates ranged from non-significance [53] to $28,553 per case [51] (across different populations for different infections, Table 3).

Table 3.

Excess Healthcare system Cost Estimates of Antimicrobial Resistance

| Study | Exposure Group | Control Group | Country | Method | Excess Cost Estimate (2013 USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost per case | |||||

| [109] | CRAB in Columbia | Carbapenem susceptible A. baumannii | Columbia | Regression | 4,583a |

| [124] | ESBL+ E. coli & Klebsiella species UTI | ESBL- E. coli & Klebsiella species UTI | USA | Significance Tests | 3,237a |

| [125] | ESBL+ E.coli BSI | ESBL- E.coli BSI | Germany | Matching | -2081 |

| [49] | ESBL+ Enterobacteriaceae BSI | ESBL- Enterobacteriaceae BSI | Switzerland | Multistate model | 10,154 |

| [45] | ESBL+ UTI | ESBL- UTI | Spain | Matching & Regression | 3146† |

| [126] | ESBL+ and/or beta-lactamases resistant UTI | Susceptible UTI | Turkey | Significance Tests | 90a |

| [126] | Ciprofloxacin resistant UTI | Ciprofloxacin susceptible UTI | Turkey | Significance Tests | 114a |

| [127] | MDR A. baumannii BSI | Susceptible A. baumannii BSI | Turkey | Significance Tests | 15,365 |

| [58] | MRSA | Non-exposure inpatients | Germany | Stepwise Calculations | 11,878 |

| [53] | MRSA breast abscess | MSSA breast abscess | USA | Matching | 515 |

| [128] | MRSA BSI | Non-exposure BSI | South Korea | Stepwise Calculations | 5216 |

| [129] | MRSA BSI (survivors) | Non-nosocomial-infected patients | South Korea | Matching | 11,627 |

| [129] | MRSA BSI (non-survivors) | Non-nosocomial-infected patients | South Korea | Matching | 15,254 |

| [51] | MRSA infections | Non-exposure inpatients | USA | Matching | 28,553a |

| [130] | MRSA colonisation & infection | Non-exposure inpatients | USA | Matching | 12,167a |

| [131] | Resistant BSI | Susceptible BSI | India | Significance Tests | 912a |

| [132] | Carbapenem-resistant device associated healthcare acquired infections ICU patients | Non-“device associated healthcare acquired infections” ICU patients | Greece | Significance Tests | 3,884a |

| [133] | VRE colonisation & infections | Non-exposure inpatients | Canada | Matching & Regression | 18,631a |

| [76] | VRE BSI | VSE BSI | Australia | Matching & Regression | 30,093a |

| [134] | VRE BSI in allo-HSCT recipients | Non-exposure in allo-HSCT recipients | USA | Significance Tests | 6104 |

| [135] | MDR TB | Non-MDR TB | Germany | Stepwise Calculations | 86,321 |

| [136] | MDR TB | Non-MDR TB | South Africa | Stepwise Calculations | 6728 |

| [137] | MDR TB | Non-MDR TB | Latvia | Regression | 33291a |

| [138] | XDR and pre-XDR TB | Rifampicin-mono-resistant or MDR TB | South Africa | Stepwise Calculations | 15,567 |

| [136] | XDR TB | Non-“XDR or MDR” TB | South Africa | Stepwise Calculations | 26,989 |

| [139] | VRE BSI in leukaemia patients | Non-exposure leukaemia patients | USA | Matching | 88150a |

| Per-patient per-day | |||||

| [50] | MRSA in Switzerland | Non-exposure inpatients | Switzerland | Multistate model | 867 |

| [140] | Resistant Gram-negative Bacilli infection | Susceptible Gram-negative Bacilli infection | Singapore | Matching | 812 |

| Annual cost per stated country or stated region | |||||

| [57] | MRSA | No-MRSA | USA | Multistate model | 1,382,733,079 |

| [141] | Resistant Streptococcus pneumonia | Susceptible Streptococcus pneumonia | USA | Multistate model | 91,773,500 |

| [142] | Artemisinin resistant malaria | No-“Artemisinin resistant malaria” | High endemicity region | Multistate model | 32,000,000 |

aStatistically significant where p-value is less than 0.05

Estimating the economic burden of AMR

From the economic perspective stepwise calculations, multistate modelling and economic models were commonly used (Table 2). Only a small number of studies were found in this perspective category, with 11 studies assessing the burden to the economy resulting from AMR. Eight of these reported an estimate for the monetary impact of resistance (Table 4). In addition, two studies found investigated the potential psycho-social impact of having multi-drug resistant Tuberculosis, concluding that many patients in the qualitative study felt that multi-drug resistant Tuberculosis increased stigma and social isolation [54], and increased the odds of incurring catastrophic costs (in which [OR = 1.61 (95% CI = 0.98–2.64), p < 0.06]) [43]. A report from ‘The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance’ did mention the secondary effects of AMR from the economic perspective, however did not attempt to quantify an exact figure for this, instead stating that some proportion of the 120 trillion USD gained from caesareans, joint operations, chemotherapy and organ transplants could be lost [1].

Table 4.

Excess Economic Burden Estimates of Antimicrobial Resistance

| Study | Exposure Group | Control Group | Country | Method | Excess Cost Estimate (2013 USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost per case | |||||

| [135] | MDR TB | Susceptible TB | Germany | Stepwise Calculation | 110,063 |

| [135] | XDR TB | Susceptible TB | Germany | Stepwise Calculation | 145,679 |

| [143] | MDR TB | Susceptible TB | Europe | Stepwise Calculation | 62,931 |

| [143]) | XDR TB | Susceptible TB | Europe | Stepwise Calculation | 215,038 |

| [56] | MRSA BSI | Non-nosocomial-infected patients | South Korea | Matching | 21,832 |

| Annual cost per stated country or stated region | |||||

| [141] | Resistant Streptococcus pneumonia | Susceptible Streptococcus pneumonia | USA | Multistate model | 236,495,000 |

| [57] | MRSA | No MRSA | USA | Multistate model | 7,848,223,600 |

| [142] | Artemisinin resistant malaria | No resistance | High endemicity regions | Decision Tree | 385,000,000 |

| Global economic cost | |||||

| [15] | Resistance globally (doubling of current infection rates and 100% resistance) | Lower rates of resistance (a 40% resistance increase from current rates) | Global | Total Factor Productivity model | 14,228,000,000 less GDP produced in 2050 compared to 2050 in a scenario with lower resistance |

| [55] | Resistance globally (100% resistance rate) | No resistance | Global | Computable General Equilibrium model | 3,158,862,360 less GDP produced in 2050 compared to 2050 with no resistance |

The only studies explicitly estimating the economic burden of AMR to include Gram-negative infections were those commissioned by ‘The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance’ (in which Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pnuemoniae were two out of six studied microbes) [1, 15, 55]. These modelling studies, which utilised economic modelling techniques, provided the largest estimates of cost (though of six resistant microbes), estimating over $14 billion to over $3 trillion (2013 USD) in loss to global GDP by 2050 [15, 55]. Whilst the studies which utilised multistate modelling techniques (including decision tree analysis) or stepwise calculations, estimated national costs for a specific resistance type to range from over $20,000 per MRSA bloodstream infection case to over $7 billion per year attributable to community acquired MRSA in the United States (Table 4) [56, 57].

Quality of included studies

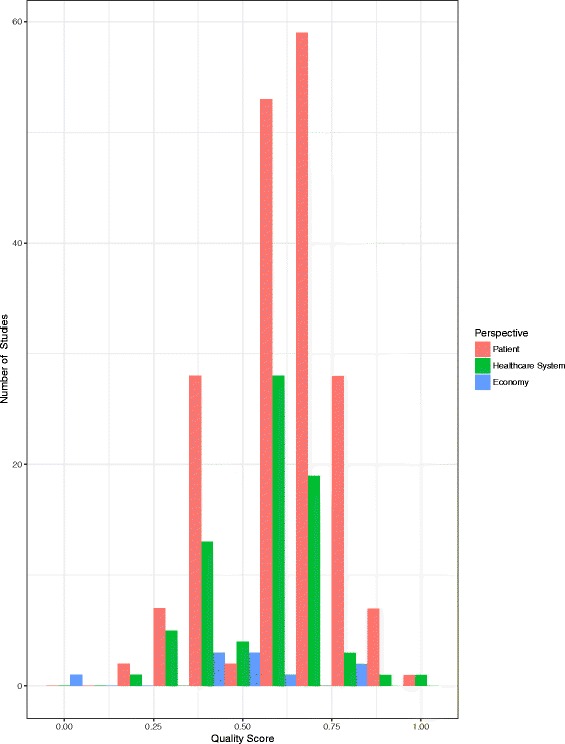

For the outcomes and exposures tested relevant to this review, 199 studies were considered cohort, 1 case-control and 13 modelling studies, whereby the stated quality checklists were then applied. One additional study was a survey-based qualitative study and was not quality assessed [54]. Median quality scores (with interquartile range (IQR)) for health, healthcare system and economic burden studies were 0.67 (0.56-0.67), 0.56 (0.46-0.67) and 0.53 (0.44-0.60) respectively. Within all perspectives, quality rarely exceeded 0.75. Notably there was a lack of economic burden studies and their median quality score was lower than that of the health and healthcare system studies (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Histograms of Quality Assessment Scores by Study Perspective

The Newcastle-Ottawa checklist criteria showed that only 54% of the total available points for adjustment/comparability of different exposure groups across all cohort studies were awarded (in all 199 studies, where two points were available per study [29]), suggesting a need for more robust analyses estimating the impact of AMR. Some of the least fulfilled quality assessment categories by studies were those that focused on representativeness of the sample utilised (18% of the appraised studies met this criteria), description/adequacy of follow-up or non-response rates (40% met this criteria) and demonstration of non-exposure before study period (8% met this criteria), across the Newcastle-Ottawa cohort quality assessment checklist (199 studies).

For the 13 studies for which the Philips checklist was utilised to assess quality, there were many indicators for which scores were generally low, including those related to descriptions of the choice of model structure and the approach to obtaining parameter values (less than 1/3 of studies obtaining the related criteria). However, of note, none of the relevant studies met the following criteria; “Have the four principal types of uncertainty been addressed?”, “If not, has the omission been justified?” and “Is there evidence that the mathematical logic of the model has been tested thoroughly before use?” [31]. Additionally, only 23% of studies used a lifetime horizon or justified why they didn’t use it and only 15% demonstrated a systematic approach to parameter selection.

Box 1: Across Perspectives: A Tuberculosis Case Study

| To illustrate the importance of clarifying the perspective chosen when investigating the burden of AMR, the case of multidrug resistant (MDR-) and extensively drug resistant (XDR-) Tuberculosis (TB) will be used, as studies of this infection-type provided cost estimates (monetary costs are 2013 USD) across perspectives (for full study details refer to Additional file 1: Table S4). |

| Patient burden: In Peruvian adult patients, it was estimated that MDR-TB was significantly associated with mortality [HR = 7.5 (95% CI; 4.1 – 13.4)] using regional network data [144]. Likewise, in American patients, using data from a national institute, XDR was found to be significantly associated with mortality [HR = 2.8 (95% CI; 1.4 – 5.4)] [145]. In South African adult patients from one hospital, both MDR and XDR were associated with increased mortality [MDR HR = 3.37, p < 0.0001, and XDR HR = 6.75, p < 0.001] [146]. All of the aforementioned studies looking into TB and mortality utilised a Cox proportional hazards approach. Another study utilised a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis methodology, and found that capromycin resistance in XDR TB was not significantly associated with mortality (p < 0.0573) [147]. Using Israeli patient data from a national registry, MDR was found to be significantly associated with TB-related death [OR = 2.83(95% CI; 1.70-4.72), p < 0.001], using a logistic regression approach [148]. |

| Healthcare system burden: MDR-TB was estimated to cost the South African healthcare system $6728 excess per case, $33,291 total per case in Latvia and $86,321 total per case in Germany using an evidence synthesis approach [135–137]. These studies included factors such as length of stay, drug costs and services consumed (varying between studies). |

| Economic burden: It was estimated, by evidence synthesis and stepwise calculation, that the total economic and societal burden costs per case for the original EU-15 states (i.e. healthcare system costs plus productivity loss, compared to susceptible TB) from MDR and XDR TB were $62,931 and $215,038 [143]. MDR-TB was also found to be independently associated with incurring catastrophic costs in Peruvian patients older than 15 years [OR = 1.61 (95% CI = 0.98–2.64)], whereby catastrophic costs were defined as total costs greater than or equal to 20% of household annual income. Costs included direct medical and non-medical out-of-pocket costs (such as excess transport and food) [43]. |

Discussion

The first aim of this review was to establish what perspectives and resulting methodologies have been used to estimate AMR burden in recent literature and to discern the impact this has on the actual estimates of burden. This review found that out of the 214 studies included, 187 studies provided an estimate of burden from the health perspective, 75 studies from the healthcare system perspective and 11 studies from the economic perspective. This review describes the large range of estimates that fall within these categories, and the methodologies used to obtain them. The most utilised methodologies were regression analysis for patient health and healthcare system burden calculations and either stepwise calculations or multistate models for economic burden estimates. An additional aim of this paper was to assess the quality of evidence for health, healthcare system and economic burden. There was a lack of economic burden studies, with the median quality score of these studies being lower than those of the health and healthcare system studies.

AMR is thought to potentially impact patient health through increasing patient mortality, though only around 50% of studies found a statistically significant impact when comparing resistant and susceptible infections. A substantial proportion of studies which used parametric regression or Cox proportional hazards techniques to estimate the impact of resistant infections in Gram-negative bacteria on mortality through OR or HR measures, had high uncertainty.

Evidence on additional length of hospital stay, a key driver of cost of infections in hospitals, was variable in terms of methodological choice and values found. A large proportion of the studies addressing length of stay in a healthcare facility did not explicitly state excess or associated length of stay, but rather estimated average length of stay for different groups and performed univariate comparisons of these averages. For those that did estimate excess length of stay, it was expected (given previous literature [28]) that multistate model length of stay estimates compared to those found using alternative methods would be more conservative. However, this review found that multistate model estimates for length of stay for MRSA infection and MRSA bloodstream infection were higher than those using stepwise analysis and regression analysis [48, 50, 58, 59]. This is likely due to the fact that the described studies were set in different countries (Australia, Germany, Switzerland and US) and were mainly single centre studies, and so less externally valid. The use of multistate modelling methods to estimate attributable health and cost burden for resistant infections has previously been recommended because standard regression techniques may overstate the attributable length of stay for hospital onset infections, thus overestimating burden of AMR [28, 60]. However, we demonstrate that very few studies took advantage of this method over the search period.

Due to the small sample of economic burden studies, no consensus on method can be stated for estimating the economic burden, though 6 out of the 11 studies did utilise evidence synthesis and stepwise approaches or multistate models. The median quality of studies quantifying the economic burden of AMR fell below those of health and healthcare system burden studies, seemingly mainly due to a lack of rigorous, transparent modelling studies which appropriately present or incorporate uncertainty.

The recent reports produced by the ‘The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance’ attempted to address the lack of economic burden estimates in the field of AMR [1, 15, 55]. However due to the large scope of these projects the models used provide only broad, general estimates (such as the global economic burden of AMR in general) which may be unsuitable for cost-effectiveness or resource allocation models. The review itself calls for the estimates to be developed using more data-driven approaches [1]. This type of analysis has also recently been called into question due to its lack of scientific scrutiny and transparency, questioning the methodology used [7].

Based on the results of this study, focusing on the results of the quality assessment of included studies, the following actions are recommended for future research in AMR burden;

Utilise data from a representative sample of the population of interest. If this is not achievable due to data limitations, create and publish a clearly defined protocol that can be utilised in other institutions. This will enable future meta-analyses to be conducted.

Choose an appropriate methodology that takes into account potential confounding factors (such as patient comorbidities or age) and biases (such as time dependency bias, competing risks or non-informative censoring).

Describe data collection, data cleaning, follow-up, response rates and/or censoring clearly, where appropriate.

Estimate healthcare system and economic impact where possible.

If performing a mathematical or economic model, clearly describe the reasons for the chosen model structure (for example by detailing a formal health economic reasoning, including for chosen time horizon) and methods of parameterisation (with structured or systematic methods preferred). In addition, it is important to discuss how methodological, structural, heterogeneity and parameter uncertainty has been addressed (or discuss why these were not addressed).

Smith and Coast reported that estimates ranged from less than $15 to around $50,000 for additional costs per patient per episode to about $20 billion per year from the societal/economic perspective (converted to 2013 USD) [8]. This review found the healthcare system excess costs ranged from just almost non-significance to over $90 million per year, whilst economic costs ranged from just over $100,000 per case to over $3 trillion total GDP loss by 2050 (in 2013 USD). Adding to the 21 studies included in the Smith and Coast 2012 review, this review discusses the results from an additional 214 studies. This review encountered a similar result to that of Smith and Coast in terms of lack of indirect burden evidence [8]. However this review did find additional evidence on the potential secondary effects of AMR, with studies estimating the potential secondary effect of AMR on health and economic burden [1, 12].

Strengths of this review include its rigorous systematic methodology and its use of accepted quality assessment scales to present the first systematic picture of the quality of recent AMR burden estimates. This is particularly important when establishing the current evidence, as previously published review studies in this area have either been commentary pieces or have not incorporated any quality assessment across all three perspectives [8, 9, 18]. One limitation of this study is that is has a relatively short search time period. This was chosen to build upon rather than duplicate the evidence produced within a previous review, and to capture recent evidence [8]. Other limitations of the review include that the Health Related Quality of Life was not included as an outcome of interest. This was beyond the scope of this review given the very different methodologies applied in order to estimate Health Related Quality of Life burden, and that the majority of discussion of patient burden currently surrounds mortality impact.

Conclusion

This study concludes that perspective affects chosen methodology and outcome for quantifying the burden of AMR. The review finds substantially more research in patient burden and seemingly more of a consensus on the most appropriate methods to use (regression or survival techniques), in comparison to healthcare system and economic burden research. However, across patient and healthcare system burden studies, a worryingly high number of studies are utilising univariate statistical significance tests, suggesting that a high proportion of this evidence is unreliable. The review also concludes that the evidence on the economic burden of AMR is not substantial, whereby the majority of studies have not used established health economic modelling techniques or adhered well to the Philip’s checklist [31]. More evidence on the secondary effect of AMR on health, healthcare system and economic burden is also needed [1, 12].

The estimates presented in this review can be used as parameter inputs in future health economics models used to inform health policy, whilst the description of previous methods used can inform future researchers’ methodology choice (based on their desired perspective). The review also highlights key areas where research is needed, including multivariate, internally and externally valid health and healthcare system burden studies. This research is needed particularly for Gram-negative bacteria. Additionally, high quality economic burden and secondary burden research is needed in general. Future AMR burden research should follow the recommendations highlighted in this review, in order to increase the quality of evidence available.

Additional file

Supplementary Material for the Systematic Literature Review. (DOCX 359 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Prof Alison Holmes and Dr Ceire Costelloe for their guidance in correspondence to the nature of this review and systematic literature reviews in general.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance at Imperial College London in partnership with Public Health England (PHE). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health or Public Health England. More information on HPRU and current projects can be found on http://www.imperial.ac.uk/medicine/hpru-amr.

Availability of data and materials

Extracted data from included studies are provided in the [Additional file 1] associated with this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 3GCR

Third-generation cephalosporin resistant

- A. baumannii

Acinetobacter baumannii

- AC

Amoxicilline-clavulanate

- Allo-HSCT

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- AMR

Antimicrobial Resistance

- BIVR

Beta-lactam induced vancomycin resistance

- BSI

Bloodstream infection

- CR

Carbapenem resistant

- CRAB

Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

- CRKP

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- ESBL

Extended Spectrum Beta-lactamase

- EUR

Euro

- GDP

Gross Domestic Product

- GN

Gram-negative

- HR

Hazard ratio

- hVISA

Heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IQR

Interquartile range

- K. pneumoniae

Klebsiella pneumoniae

- KPC

Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase

- LoS

Length of stay

- MBL

Metallo-beta-lactamase

- MDR

Multidrug resistance

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MLSR

Macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin resistance

- MRSA

Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- MSSA

Methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus

- NDM-1

New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase-1

- OR

Odds ratio

- P. aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- PDR

Pan drug resistant

- res.

Resistant

- S. aureus

Staphylococcus aureus

- sus.

Susceptible

- TB

Tuberculosis

- USD

United States Dollars

- UTI

Urinary tract infection

- VAP

Ventilator associated pneumonia

- VRE

Vancomycin resistant Enterococcus

- VSE

Vancomycin susceptible Enterococcus

- XDR

Extensively drug resistant

Authors’ contributions

NN, GK, JR, RA, NZ, KK and SS created the final protocol. NN performed the searches, independent reviews, data collection and data analysis. NZ, KK and SS performed the independent reviews. All authors contributed to the drafting of the final manuscript, especially in how to present the results and data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

NN is currently undertaking a PhD funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13756-018-0336-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Nichola R. Naylor, Phone: +447966889435, Email: n.naylor@imperial.ac.uk

Rifat Atun, Email: ratun@hsph.harvard.edu.

Nina Zhu, Email: jiayue.zhu09@imperial.ac.uk.

Kavian Kulasabanathan, Email: kavian.kulasabanathan12@imperial.ac.uk.

Sachin Silva, Email: sas7443@mail.harvard.edu.

Anuja Chatterjee, Email: a.chatterjee15@imperial.ac.uk.

Gwenan M. Knight, Email: g.knight@imperial.ac.uk

Julie V. Robotham, Email: julie.robotham@phe.gov.uk

References

- 1.The AMR Review . Antimicrobial Resistance : Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health England . English surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR) 2014. pp. 1–143. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Current. 2013:1–114.

- 4.European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control The European Union Summary Report on antimicrobial resistance in Antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in the European Union in 2014. EFSA J. 2016;14:1–207. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health England. New report shows stark effect of antibiotic resistance [Internet]. 2014. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-report-shows-stark-effect-of-antibiotic-resistance. [cited 15 May 2016].

- 6.Husereau D, Drummond MPS. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS)—Explanation and elaboration: A report of the ISPOR health economic evaluations publication guidelines good reporting practices task force. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Kraker MEA, Stewardson AJ, Harbarth S. Will 10 Million People Die a Year due to Antimicrobial Resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 2016;13:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith R, Coast J. The economic burden of antimicrobial resistance: why it is more serious than current studies suggest. London: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Angelis G, D’Inzeo T, Fiori B, Spanu T, Sganga G. Burden of Antibiotic Resistant Gram Negative Bacterial Infections: Evidence and Limits. J Med Microbiol Diagn. 2014;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs P, Fassbender K. The measurement of indirect costs in the health economics evaluation literature. A review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1998;14:799–808. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300012095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tam CC, O’Brien SJ. Economic cost of campylobacter, norovirus and rotavirus disease in the United Kingdom. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teillant A, Gandra S, Barter D, Morgan DJ, Laxminarayan R. Potential burden of antibiotic resistance on surgery and cancer chemotherapy antibiotic prophylaxis in the USA: A literature review and modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:1429–1437. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert ML, Suetens C, Savey A, Palomar M, Hiesmayr M, Morales I, et al. Clinical outcomes of health-care-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance in patients admitted to European intensive-care units: A cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:30–38. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alam MF, Cohen D, Butler C, Dunstan F, Roberts Z, Hillier S, et al. The additional costs of antibiotics and re-consultations for antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli urinary tract infections managed in general practice. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:255–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.KPMG . The global economic impact of antimicrobial resistance. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yao Z, Peng Y, Chen X, Bi J, Li Y, Ye X, et al. Healthcare associated infections of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A case-control-control study. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewardson AJ, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Graves N, Schumacher M, Meyer R, et al. The health and economic burden of bloodstream infections caused by antimicrobial-susceptible and non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae and Staphylococcus aureus in European hospitals, 2010 and 2011: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Eur Secur. 2016;21:1–12. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.33.30319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandra S, Barter DM, Laxminarayan R. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance: how much do we really know? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:973–980. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cosgrove SE, Carmeli Y. The Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance on Health and Economic Outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1433–1437. doi: 10.1086/375081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilton P, Smith R, Coast J, Millar M. Strategies to contain the emergence of antimicrobial resistance: a systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:111–117. doi: 10.1258/1355819021927764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallagher J. Antibiotic resistance: World on cusp of “post-antibiotic era” [Internet]. BBC. 2015. Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-34857015. [cited 1 Nov 2016].

- 22.Department of Health, Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs . UK Five Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2013 to 2018. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naylor N, Silva S, Kulasabanathan K, Atun R, Zhu N, Knight G, et al. How to estimate the burden of antimicrobial resistance: a systematic literature review [Internet]. PROSPERO. 2016. Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016037510. [cited 13 Jul 2016].

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews an Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:1–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naylor NR, Silva S, Kulasabanathan K, Atun R, Zhu N, Knight GM, et al. Methods for estimating the burden of antimicrobial resistance : a systematic literature review protocol. Syst Rev. 2016;5:187. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0364-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.PubMed [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/. [cited 10 Jan 2018].

- 27.Takizawa C, Thompson PL, Van Walsem A. Epidemiological and Economic Burden of Alzheimer ’ s Disease : A Systematic Literature Review of Data across Europe and the United States of America. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:1271–1284. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graves N, Harbarth S, Beyersmann J, Barnett A, Halton K, Cooper B. Estimating the cost of health care-associated infections: mind your p’s and q’s. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1017–1021. doi: 10.1086/651110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells G., Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [Internet]. University of Ottawa. 2014. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. [cited 1 Feb 2016].

- 30.Song J, Chung K. Observational Studies: Cohort and Case-Control Studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;126:2234–2242. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f44abc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philips Z, Bojke L, Sculpher M, Claxton K, Golder S. Good Practice Guidelines for Decision-Analytic Modelling in Health Technology Assessment. PharmacoEconomics. 2006;24:355–371. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200624040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Table 7.7.a: Formulae for combining groups

- 33.Rate Inflation. Historical Inflation Rates for Australia (2007 to 2017) [Internet]. 2017. Available from: http://www.rateinflation.com/inflation-rate/australia-historical-inflation-rate. [cited 10 Jan 2017].

- 34.Triami Media BV. Historic Inflatin - CPI inflation year pages [Internet]. inflation.eu. 2017. Available from: www.inflation.eu. [cited 12 Feb 2017].

- 35.UKForex. Yearly Average Rates [Internet]. 2017. Available from: www.ukforex.co.uk/forex-tools/historical-rate-tools/yearly-average-rates. [cited 12 Nov 2017].

- 36.Wickham H, Chang W, RStudio. ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics [Internet]. 2016. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/package=ggplot2

- 37.Wickham H. The Split-Apply-Combine Strategy for Data Analysis. J Stat Softw. 2011;40:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viechtbauer W. Package “metafor.” 2017.

- 39.Bodro M, Sanclemente G, Lipperheide I, Allali M, Marco F, Bosch J, et al. Impact of antibiotic resistance on the development of recurrent and relapsing symptomatic urinary tract infection in kidney recipients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:1021–1027. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qureshi ZA, Syed A, Clarke LG, Doi Y, Shields RK. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of patients with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriuria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1–18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02445-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vazirani J, Wurity S, Ali MH. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis: Risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2110–2114. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Francis JR, Blyth CC, Colby S, Fagan JM, Waring J. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Western Australia, 1998–2012. Med J Aust. 2014;200:328–332. doi: 10.5694/mja13.11342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wingfield T, Boccia D, Tovar M, Gavino A, Zevallos K, Montoya R, et al. Defining Catastrophic Costs and Comparing Their Importance for Adverse Tuberculosis Outcome with Multi-Drug Resistance: A Prospective Cohort Study, Peru. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rello J, Molano D, Villabon M, Reina R, Rita-Quispe R, Previgliano I, et al. Differences in hospital- and ventilator-associated pneumonia due to Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant) between Europe and Latin America: a comparison of the EUVAP and LATINVAP study cohorts. Med Intensiva. 2013;37:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esteve-Palau E, Solande G, Sanchez F, Sorli L, Montero M, Guerri R, et al. Clinical and economic impact of urinary tract infections caused by ESBL-producing Escherichia coli requiring hospitalization: A matched cohort study. J Infect. 2015;71:667–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ong SJ, Huang Y-C, Tan H-Y, Ma DHK, Lin H-C, Yeh L-K, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Keratitis: A Review of Hospital Cases. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kini AR, Shetty V, Kumar AM, Shetty SM, Shetty A. Community-associated, methicillin-susceptible, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bone and joint infections in children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2013;22:158–166. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e32835c530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnett AG, Page K, Campbell M, Martin E, Rashleigh-Rolls R, Halton K, et al. The increased risks of death and extra lengths of hospital and ICU stay from hospital-acquired bloodstream infections: a case-control study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003587. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stewardson A, Fankhauser C, De Angelis G, Rohner P, Safran E, Schrenzel J, et al. Burden of bloodstream infection caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae determined using multistate modeling at a Swiss University Hospital and a nationwide predictive model. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:133–143. doi: 10.1086/669086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macedo-Viñas M, De Angelis G, Rohner P, Safran E, Stewardson A, Fankhauser C, et al. Burden of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections at a Swiss University hospital: excess length of stay and costs. J Hosp Infect. 2013;84:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson RE, Samore MH, Jones M, Greene T, Stevens VW, Liu CF, et al. Reducing Time-dependent Bias in Estimates of the Attributable Cost of Health Care-associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections: A Comparison of Three Estimation Strategies. Med Care. 2015;53:827–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leistner R, Gürntke S, Sakellariou C, Denkel LA, Bloch A, Gastmeier P, et al. Bloodstream infection due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-positive K. pneumoniae and E. coli: an analysis of the disease burden in a large cohort. Infection. 2014;42:991–997. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0670-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Branch-Elliman W, Lee GM, Golen TH, Gold HS, Baldini LM, Wright SB. Health and Economic Burden of Post-Partum Staphylococcus aureus Breast Abscess. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris MD, Quezada L, Bhat P, Moser K, Smith J, Perez H, et al. Social, Economic, and Psychological Impacts of MDR-TB Treatment in Tijuana, Mexico: A Patient’s Perspective. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:954–960. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor J, Hafner M, Yerushalmi E, Smith R, Bellasio J, Vardavas R, et al. Estimating the economic costs of antimicrobial resistance. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee JY, Chong YP, Kim T, Hong HL, Park SJ, Lee ES, et al. Bone and joint infection as a predictor of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: A comparative cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1966–1971. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee BY, Singh A, David MZ, Bartsch SM, Slayton RB, Huang SS, et al. The economic burden of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:528–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hübner C, Hübner NO, Hopert K, Maletzki S, Flessa S. Analysis of MRSA-attributed costs of hospitalized patients in Germany. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1817–1822. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Micek ST, Kollef MH. Outcomes associated with bacteremia in the setting of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2015;19:312. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Graves N, Weinhold D, Roberts JA. Correcting for bias when estimating the cost of hospital-acquired infection: an analysis of lower respiratory tract infections in non-surgical patients. Health Econ. 2005;14:755–761. doi: 10.1002/hec.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rieg S, Jonas D, Kaasch AJ, Porzelius C, Peyerl-Hoffmann G, Theilacker C, et al. Microarray-Based Genotyping and Clinical Outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infection: An Exploratory Study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Manandhar S, Pai G, Gidwani H, Nazim S, Buehrle D, Shutt KA, et al. Does Staphylococcus aureus Bacteriuria Predict Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Bacteremia? Analysis of 274 Patients With Staphylococcus aureus Blood Stream Infection. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2016;24:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Theodorou P, Lefering R, Perbix W, Spanholtz TA, Maegele M, Spilker G, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia after thermal injury: The clinical impact of methicillin resistance. Burns. 2013;39:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cobos-Carrascosa E, Soler-Palacín P, Nieves Larrosa M, Bartolomé R, Martín-Nalda A, Antoinette Frick M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:1329–1334. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hernández C, Feher C, Soriano A, Marco F, Almela M, Cobos-Trigueros N, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of elderly patients with community-onset bacteremia. The Journal of infection. 2014;70:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Okada Y, Hosono M, Sasaki Y, Hirai H, Suehiro S. Preoperative increasing C-reactive protein affects the outcome for active infective endocarditis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;20:48–54. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.12.02091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yavuz SŞ, Şensoy A, Çeken S, Deniz D, Yekeler I. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection: An independent risk factor for mortality in patients with poststernotomy mediastinitis. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23:517–523. doi: 10.1159/000365055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sakoda Y, Ikegame S, Ikeda-Harada C, Takakura K, Kumazoe H, Wakamatsu K, et al. Retrospective analysis of nursing and healthcare-associated pneumonia: Analysis of adverse prognostic factors and validity of the selection criteria. Respiratory Investigation. 2014;52:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takata T, Miyazaki M, Futo M, Hara S, Shiotsuka S, Kamimura H, et al. Presence of both heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate resistance and β-lactam antibiotic-induced vancomycin resistance phenotypes is associated with the outcome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45:203–212. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.723221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hu H-C, Kao K-C, Chiu L-C, Chang C-H, Hung C-Y, Li L-F, et al. Clinical outcomes and molecular typing of heterogenous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in patients in intensive care units. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:444. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1215-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee H-Y, Chen C-L, Liu S-Y, Yan Y-S, Chang C-J, Chiu C-H. Impact of Molecular Epidemiology and Reduced Susceptibility to Glycopeptides and Daptomycin on Outcomes of Patients with Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee JK, Lee J, Park YS, Lee CH, Yim JJ, Yoo CG, et al. Clinical manifestations of pneumonia according to the causative organism in patients in the intensive care unit. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:829–836. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.30.6.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hope R, Blackburn RM, Verlander NQ, Johnson A, Kearns A, Hill R, et al. Vancomycin MIC as a predictor of outcome in MRSA bacteraemia in the UK context. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2641–2647. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tadros M, Williams V, Coleman BL, McGeer AJ, Haider S, Lee C, et al. Epidemiology and Outcome of Pneumonia Caused by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Canadian Hospitals. PLoS One. 2013;8:4–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Castón JJ, González-Gasca F, Porras L, Illescas S, Romero MD, Gijón J. High vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration is associated with poor outcome in patients with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia regardless of treatment. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46:783–786. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2014.931596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cheah ALY, Spelman T, Liew D, Peel T, Howden BP, Spelman D, et al. Enterococcal bacteraemia: Factors influencing mortality, length of stay and costs of hospitalization. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:E181–E189. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kang C-I, Song J-H, Kim SH, Chung DR, Peck KR, Thamlikitkul V, et al. Association of levofloxacin resistance with mortality in adult patients with invasive pneumococcal diseases: a post hoc analysis of a prospective cohort. Infection. 2013;41:151–157. doi: 10.1007/s15010-012-0299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fu Q, Ye H, Liu S. Risk factors for extensive drug-resistance and mortality in geriatric inpatients with bacteremia caused by Acinetobacter baumannii. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:857–860. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kitazono H, Rog D, Sa G, Nm C, Acinetobacter RGE. Acinetobacter baumannii infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin Transpl. 2015:227–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Park SY, Choo JW, Kwon SH, Yu SN, Lee EJ, Kim TH, et al. Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with Acinetobacter baumannii Bacteremia. Infect Chemother. 2013;45:325–330. doi: 10.3947/ic.2013.45.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Jager P, Chirwa T, Naidoo S, Perovic O, Thomas J. Nosocomial outbreak of New Delhi metallo-Beta-lactamase-1-producing Gram-negative bacteria in South Africa: A case-control study. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang HT, Liu H. Laboratory-based evaluation of MDR strains of Pseudomonas in patients with acute burn injuries. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:16512–16519. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Samonis G, Vardakas KZ, Kofteridis DP, Dimopoulou D, Andrianaki AM, Chatzinikolaou I, et al. Characteristics, risk factors and outcomes of adult cancer patients with extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Infection. 2014;42:721–728. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0635-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Theodorou P, Thamm O, Perbix W, Phan V. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia after burn injury: The impact of multiple-drug resistance. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34:649–658. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318280e2c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Micek ST, Kollef MH, Torres A, Chen C, Rello J, Chastre J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Nosocomial Pneumonia: Impact of Pneumonia Classification. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:1190–1197. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Keddy KH, Sooka A, Musekiwa A, Smith AM, Ismail H, Tau NP, et al. Clinical and microbiological features of salmonella meningitis in a South African Population, 2003-2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:S272–S282. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tumbarello M, Trecarichi EM, De Rosa FG, Giannella M, Giacobbe DR, Bassetti M, et al. Infections caused by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: Differences in therapy and mortality in a multicentre study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;70:2133–2143. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Capone A, Giannella M, Fortini D, Giordano A, Meledandri M, Ballardini M, et al. High rate of colistin resistance among patients with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection accounts for an excess of mortality. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:E23–E30. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hussein K, Raz-Pasteur A, Finkelstein R, Neuberger A, Shachor-Meyouhas Y, Oren I, et al. Impact of carbapenem resistance on the outcome of patients’ hospital-acquired bacteraemia caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Hosp Infect. 2013;83:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Biehle LR, Cottreau JM, Thompson DJ, Filipek RL, O’Donnell JN, Lasco TM, et al. Outcomes and risk factors for mortality among patients treated with carbapenems for klebsiella spp. bacteremia. PLoS One. 2015;10:6–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Andria N, Henig O, Kotler O, Domchenko A, Oren I, Zuckerman T, et al. Mortality burden related to infection with carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria among haematological cancer patients: A retrospective cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:3146–3153. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Papadimitriou-Olivgeris M, Marangos M, Fligou F, Christofidou M, Sklavou C, Vamvakopoulou S, et al. KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae enteric colonization acquired during intensive care unit stay: the significance of risk factors for its development and its impact on mortality. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Abernethy JK, Johnson AP, Guy R, Hinton N, Sheridan EA, Hope RJ. Thirty day all-cause mortality in patients with Escherichia coli bacteraemia in England. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:251. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bergin SP, Thaden JT, Ericson JE, Cross H, Messina J, Clark RH, et al. Neonatal Escherichia coli Bloodstream Infections: Clinical Outcomes and Impact of Initial Antibiotic Therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:933–936. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Denis B, Lafaurie M, Donay JL, Fontaine JP, Oksenhendler E, Raffoux E, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and impact on clinical outcome of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli bacteraemia: A five-year study. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;39:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim S-H, Kwon J-C, Choi S-M, Lee D-G, Park SH, Choi J-H, et al. Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in patients with neutropenic fever: factors associated with extended-spectrum β-lactamase production and its impact on outcome. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:533–541. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1631-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rodríguez-Baño J, Mingorance J, Fernández-Romero N, Serrano L, López-Cerero L, Pascual A. Outcome of bacteraemia due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: Impact of microbiological determinants. J Infect. 2013;67:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ha YE, Kang C-II, Cha MK, Park SY, Wi YM, Chung DR, et al. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in patients with cancer. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;42:403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hernandez C, Cobos-Trigueros N, Feher C, Morata L, De La Calle C, Marco F, et al. Community-onset bacteraemia of unknown origin: clinical characteristics, epidemiology and outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1973–1980. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Seboxa T, Amogne W, Abebe W, Tsegaye T, Azazh A, Hailu W, et al. High mortality from blood stream infection in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, is due to antimicrobial resistance. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chaulk J, Carbonneau M, Qamar H, Keough A, Chang HJ, Ma M, et al. Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a single-centre experience and summary of existing studies. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:83–88. doi: 10.1155/2014/429536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Huh K, Kang CI, Kim J, Cho SY, Ha YE, Joo EJ, et al. Risk factors and treatment outcomes of bloodstream infection caused by extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacter species in adults with cancer. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Haeusler GM, Mechinaud F, Daley AJ, Starr M, Shann F, Connell TG, et al. Antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative Bacteremia in Pediatric Oncology Patients—Risk Factors and Outcomes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:723–726. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828aebc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nelson RE, Stevens VW, Jones M, Samore MH, Rubin MA. Health care associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections increases the risk of postdischarge mortality. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nitta H, Beppu T, Itoyama A, Higashi T, Sakamoto K, Nakagawa S, et al. Poor outcomes after hepatectomy in patients with ascites infected by methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Journal of Hepatobiliary-Pancreatic Sciences. 2015;22:166–176. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tavadze M, Rybicki L, Mossad S, Avery R, Yurch M, Pohlman B, et al. Risk factors for vancomycin-resistant enterococcus bacteremia and its influence on survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:1310–1316. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cho S-Y, Lee D-G, Choi S-M, Kwon J-C, Kim S-H, Choi J-K, et al. Impact of vancomycin resistance on mortality in neutropenic patients with enterococcal bloodstream infection: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:504. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chusri S, Chongsuvivatwong V, Rivera JI, Silpapojakul K, Singkhamanan K, McNeil E, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Hospital-Acquired Infection with Acinetobacter nosocomialis and Acinetobacter pittii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4172–4179. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02992-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lemos EV, de la Hoz FP, Alvis N, Einarson TR, Quevedo E, Castañeda C, et al. Impact of carbapenem resistance on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with Acinetobacter baumannii infection in Colombia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:174–180. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Inchai J, Pothirat C, Bumroongkit C, Limsukon A, Khositsakulchai W, Liwsrisakun C. Prognostic factors associated with mortality of drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia. Journal of Intensive Care. 2015;3:9. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0077-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Henig O, Weber G, Hoshen MB, Paul M, German L, Neuberger A, et al. Risk factors for and impact of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii colonization and infection: matched case-control study. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 2015;34:2063–2068. doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]