Abstract

In higher plants, ω-3 fatty acid desaturases are the key enzymes in the biosynthesis of alpha-linolenic acid (18:3), which plays key roles in plant metabolism as a structural component of both storage and membrane lipids. Here, the first ω-3 fatty acid desaturase gene was identified and characterized from oil palm. The bioinformatic analysis indicated it encodes a temperature-sensitive chloroplast ω-3 fatty acid desaturase, designated as EgFAD8. The expression analysis revealed that EgFAD8 is highly expressed in the oil palm leaves, when compared with the expression in the mesocarp. The heterologous expression of EgFAD8 in yeast resulted in the production of a novel fatty acid 18:3 (about 0.27%), when fed with 18:2 in the induction culture. Furthermore, to detect whether EgFAD8 could be induced by the environment stress, we detected the expression efficiency of the EgFAD8 promoter in transgenic Arabidopsis treated with low temperature and darkness, respectively. The results indicated that the promoter of EgFAD8 gene could be significantly induced by low temperature and slightly induced by darkness. These results reveal the function of EgFAD8 and the feature of its promoter from oil palm fruits, which will be useful for understanding the fuction and regulation of plastidial ω-3 fatty acid desaturases in higher plants.

Introduction

Linolenic acid (18:3) plays important roles in plant metabolism as a structural component of storage and membrane lipids, and as a precursor of signaling molecules involved in plant development and stress response [1,2]. For human, alpha-linoenic acid (18:3 ω-3) is one of essential fatty acids, which are necessary for health and must be acquired from diet [3]. Moreover, 18:3 is a metabolic precursor for long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs) synthesis [4], such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5Δ5,8,11,14,17, ω-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6Δ4,7,10,13,16,19, ω-3). They are essential constituents of human nutrition, and play key roles in brian and cardiovascular health [5–8]. However, the primary source of EPA and DHA is the marine product, especially fish oil [9].

In higher plants, fatty acids are synthesized de novo in the stroma of plastids through a complex series of condensation reactions to produce either C16 or C18 fatty acids. These fatty acids are then incorporated into the two glycerolipid synthetic pathways: the prokaryotic pathway and eukaryotic pathway [10,11]. Chloroplast galactolipids contain substantial amounts of trienoic fatty acid, either the hexatrienoic acid (16:3) or 18:3, which may vary in different plant species [12]. In both glycerol pathways, desaturation of fatty acids is performed by a series of membrane-bound desaturases of the chloroplast and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [2,11].

Fatty acid desaturases are encoded by nuclear genes and differ in the substrate specificity and subcellular localization, and play critical roles in maintaining proper structure and cellular function of biological membranes [2,13,14]. Stearoyl ACP desaturase (SAD) is the only soluble desaturase, which convertes stearoyl-ACP (18:0-ACP) to oleic acid (18:1-ACP) by introducing the first double bond at the 9th position from the carboxylic end of the fatty acyl chain in the process of fatty acid synthesis [14,15]. Furhter desaturations are carried out by membrane-bound desaturases in the ER (FAD2 and FAD3) and the chloroplast (FAD4, FAD5, FAD6, FAD7, and FAD8) as we mentioned before. FAD2 and FAD6 are ω-6 desaturases that synthesize linolenic acid (18:2) from oleic acid (18:1) by introduction of a double bond at the 12th position from carboxylic end or 6th position from the ω end in the ER and plastid, respectively. While, FAD3, FAD7, and FAD8 are ω-3 desaturases that desaturase 18:2 to 18:3 by inserting a double bond at the 15th position from the carboxylic end or 3rd position from the ω end. Moreover, the FAD8 gene encodes a plastidial ω-3 desaturase that is cold-inducible, which can compensate the decreased expression of FAD7 under the low temperature [16,17]. FAD4 and FAD5 synthesize 16:1 from 16:0 specifically for the main component of chloroplast membrane phosphatidylglycerol and monogalactosyldiacylglycerol, respectively [15].

The genes encoding ω-3 fatty acid desaturases have been identified and studied from several plant species, such as Arabidopsis [16,18,19], soybean [11,13,20], Zea mays [21], olive [1,22], safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) [23], Jatropha curcas [24], and flax [25]. Microsomal FAD3 enzymes have been shown to be the major contributors to seed 18:3 content in Arabidopsis, soybean, and flax [14,18,20,25]. On the contrary, the overexpression of a chloroplast ω-3 fatty acid desaturase was demonstrated to enhance the tolerance to low temperatures [26,27]. Furthermore, overexpression of ω-3 fatty acid desaturases BnFAD3 from Brassica napus and StFAD7 from Solanum tuberosum in tomato enhanced resistance to cold stress, and altered fatty acid composition with an increase in the 18:3/18:2 ratio in leaves and fruits [28]. Increased desaturation of glycerolipids severs as compensation to cold-caused decrease in membrane fluidity [29,30]. Thus, plant desaturases are very sensitive to several environmental cues such as temperature, light, or other factors [11,31].

Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) is the most productive oil-bearing crop in the world [32]. It is native to West Africa, but is now grown thuoughout the humid tropical lowlands [33,34]. There are two major economic productions from oil palm fruits: palm oil extracted from the mesocarp and palm kernel oil from the endosperm [35,36]. Palm oil contains oleate (18:1; 45%), linoleate (18:2; 8%), and 47% saturated fatty acid (43% of 16:0 and 4% of 18:0). Therefore, much effort has been made to understand the oil synthesis in oil palm fruits and improve the fatty acid composition of palm oil since the high content of saturated fatty acid has been thought to be unhealthy to human [37]. The activity of a Δ12 fatty acid desaturase from oil palm has been tested in yeast, and it produced about 12% of linoleic acid in yeast, which barely exist in wild-type yeast cells [38]. Recently, the in vivo function of a DGAT2 gene from oil palm mesocarp has been verified in yeast and transgenic Arabidopsis, exhibiting a substrate preference towards unsaturated fatty acids [39].

In the present work, a chloroplast ω-3 fatty acid desaturase (EgFAD8) and its promoter from oil palm has been isolated and characterized. The expression pattern of EgFAD8 in leaves and mesocarp at five developmental stages has been detected by Real-time quantitative PCR. The in vivo function of EgFAD8 has been verified by overexpression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (INVSc1) with exogenous linoleic acid (18:2). To detect whether it could be induced by low temperature or the change of environment, we detected the efficiency of the EgFAD8 promoter in transgenic Arabidopsis treated with low temperature and darkness, respectively. These results revealed the function of EgFAD8 and the feature of its promoter from high plants, which will be useful for understanding the role of ω-3 fatty acid desaturases from fruits grown in the tropical areas.

Materials and methods

Materials

Ethics statement

No specific permissions were required for these locations/activities. We confirmed that the field studies did not involve endangered or protected species.

Oil palm fruits were collected from the Coconut Research Institute, Chinese Agricultural Academy of Tropical Crops, Wenchang, Hainan, China. Fruits at five developmental stages (30–60 days after pollination (DAP), 60–100 DAP, 100-12- DAP, 120–140 DAP, and 140–160 DAP) were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until use. Wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia was used in this study. Arabidopsis plants were cultivated in a growth chamber at 23°C with a 16-h photoperiod (16 h of 150 μE m-2 sec-1 light and 8 h of darkness). Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) strain INVSc1 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2 trp1-289 ura3-52/MATα his3Δ1 leu2 trp1-289 ura3-52) and the high copy number shuttle vector pYES2 (Invitrogen, USA) were used for gene function analysis.

Bioinformatic analysis

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence analyses used the BLAST program and open reading frame (ORF) finder from NCBI website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Amino acid alignment of fatty acid desaturases was performed by ClustalX 2.1 program with default setting [40]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA5 [41]. Promoter prediction and cis-acting regulatory element analysis were carried out on the PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) [42].

Cloning of EgFAD8 gene

Total RNA from mesocarp was extracted by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) based method as described previously [43]. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using FastQuant RT Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) according to manufacturer’s instructions, and was used for gene cloning and expression analysis. The coding sequence of EgFAD8 was amplified by Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) using primers EgFAD8-pYES2 F and R with restriction site KpnI and XbaI, respectively (Table 1). PCR was performed with an initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30s, 30 cycles at of 98 °C for 10 s, 56 °C for 30s, 72 °C for 60 s and a final extension step of 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR product was cloned into the pEASY-Blunt vector (Transgen biotech, Beijing, China) and sequenced. The cloning of EgFAD8 promoter region sequence has been published in our previous study [44].

Table 1. List of primers used in the study.

| Primers | Sequence |

|---|---|

| EgFAD8-pYES2 F | 5’-TAGGTACCATGGCGAGTTGGGTTCTATC-3’ (KpnI) |

| EgFAD8-pYES2 R | 5’-GCTCTAGATCAATCTGAGTTCTTCTGTGAAA-3’ (XbaI) |

| RT-EgFAD8 F | 5’-TAACGGGAAACGGGTGAA-3’ |

| RT-EgFAD8 R | 5’-CCATCCAGTTATTGAGGTAGG-3’ |

| RT-β-actin F | 5’-TGGAAGCTGCTGGAATCCAT-3’ |

| RT-β-actin R | 5’-TCCTCCACTGAGCACAACGTT-3’ |

Gene expression in Saccharomyces. cerevisiae

In order to generate a yeast expression construct, EgFAD8 fragments were digested with KpnI and XbaI from pEASY vector, and subcloned into pYES2 vector. The construct EgFAD8-pYES2 and the control pYES2 were separately transformed into INVSc1 cells using the polyethylene glycol/lithium acetate method [45,46]. Transformants were selected on synthetic complete medium lacking uracil (SC-U) supplemented with 2% (w/v) glucose. Three independent positive clones of each transformation were used for further expression studies.

Precultures were made in 2 mL SC-U medium with 2% (w/v) raffinose and 1% (w/v) tergitol NP-40 (Sigma, USA), and were grown overnight at 30°C. For induction gene expression, appropriate amount of precultures were inoculated into 20 mL SC-U medium containing 2% (w/v) galactose and 50 μM linoleic acid at an OD600 of 0.1. Yeast cultures were incubated for three days at 30°C under continuous agitation (250 rpm). Then the cells were harvested and washed twice with sterile deionized water before used for fatty acid analysis.

Fatty acid analysis

Yeast cells were directly transmethylated by 2 mL of methanol containing 2.7% (v/v) H2SO4 at 80°C for 2 hours. Then, 3 mL of Hexane was added for recovering fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs), and 2 mL of NaCl (2.5%, w/v) was used for phase separation. After centrifuge, the upper hexane phase was transferred to a fresh tube and applied for gas chromatography (GC) analysis.

Exogenous application of low temperature and light treatments

Ten-day-old seedlings of the T3 generation of transgenic Arabidopsis were subjected to stress treatments. For low temperature and light treatments, transgenic plants were planted at 15°C and in dark, respectively, with other conditions are the same with the control (as mentioned in Materials). Quantitative analysis of GUS activity in each plant was carried out after treatments for 24h and 48h.

Histochemical staining and fluorometric GUS assay

For histochemical GUS staining, various tissues of Arabidopsis were incubated in GUS assay buffer with 2 mM X-Gluc, 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 100 mM Na3PO4 (pH 7.0), 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 0.2% Triton X-100 and 10 mM EDTA at 37°C overnight under the darkness, and then cleared with 70% ethanol [47]. The samples were viewed by stereo-microscopy.

Quantitative analysis of GUS activity in transgenic Arabidopsis was determined according to Jefferson [47]. The protein concentrations of plant extracts were measured as descried by Bradford [48]. GUS activity was calculated as pmol 4-Methylumbelliferone (4-MU) per min per microgram protein. Three replicates were performed for each sample.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA from mature leaves and mesocarp at five developmental stages were extracted as described previously, and cDNAs was used for real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). EgFAD8 RT-PCR primers RT-EgFAD8 F/R (Table 1) were designed for RT-qPCR. The housekeeper gene β-actin (RT-β-actin F/R, Table 1) was used as an internal control for expression analysis. RT-qPCR was carried out using a CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and SYBR® premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNaseH Plus) Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expression was quantified as comparative threshold cycle (Ct) using 2–ΔΔCt method [49]. Reactions were in triplicate including template-free and no-reverse-transcriptase negative controls.

Results

Cloning and bioinformatic analysis of EgFAD8

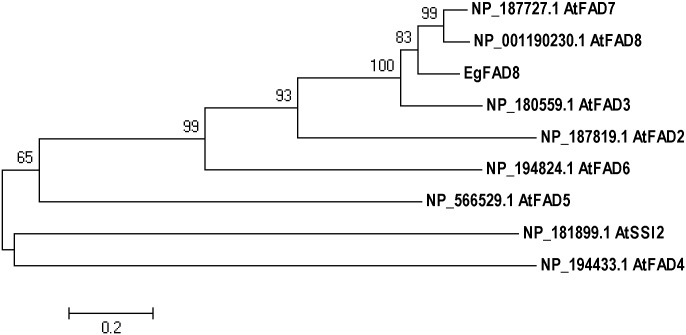

The open reading frame (ORF) cDNA sequence (1362 bp) of a ω-3 fatty acid desaturase (designated as EgFAD8) was cloned from oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) mesocarp based on that gene sequence from Elaeis oleifera (GenBank accession: EU057620.1) using RT-PCR. The nucleotide sequence is 100% identity with that from Elaeis oleifera. It encodes a 453-amino acid polypeptide with the conserved domain of ω-3 fatty acid desaturase (amino acids 1–443), which is predicted to be chloroplastic. The protein BLAST analysis of EgFAD8 showed that it shared high homology (more than 70%) with other members of the ω-3 desaturase enzyme family. Phylogenetic analysis of EgFAD8 with various fatty acid desaturases from model plant Arabidopsis thaliana revealed that EgFAD8 clusters with two chloroplastic ω-3 fatty acid desaturases AtFAD7 and AtFAD8, as well as the endoplasmic reticulum-type ω-3 fatty acid desaturase AtFAD3 (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Phylogenetic analysis of EgFAD8 and fatty acid desaturases from Arabidopsis thaliana.

A neighbor-joining tree was generated by MEGA5 with bootstrap analysis based on 1000 replications. Bootstrap values are shown at branch points. Scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site.

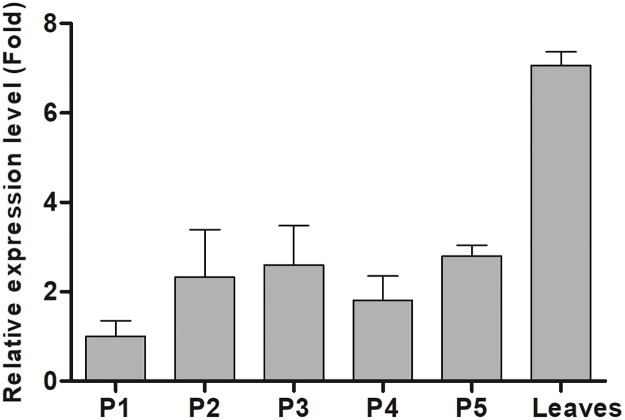

Expression pattern of EgFAD8 in leaf and mesocarp during fruit development

The transcript levels of EgFAD8 in leaf and mesocarp at five different developmental stages were determined by RT-qPCR using β-actin as an internal control. The results showed that the transcript level of EgFAD8 in mesocarp was quite flat during ripening with a slight increase at the beginning (from P1 to P2, Fig 2). Interestingly, the expression level of EgFAD8 in mature leaves was at least twice that in mescoarp (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Expression analysis of EgFAD8 in oil palm leaves and mesocarp at five different developmental stages.

P1: mesocarp at 30–60 DAP; P2: mesocarp at 60–100 DAP; P3: mesocarp at 100–120 DAP; P4: mesocarp at 120–140 DAP; P5: mesocarp at 140–160 DAP. DAP: days after pollination.

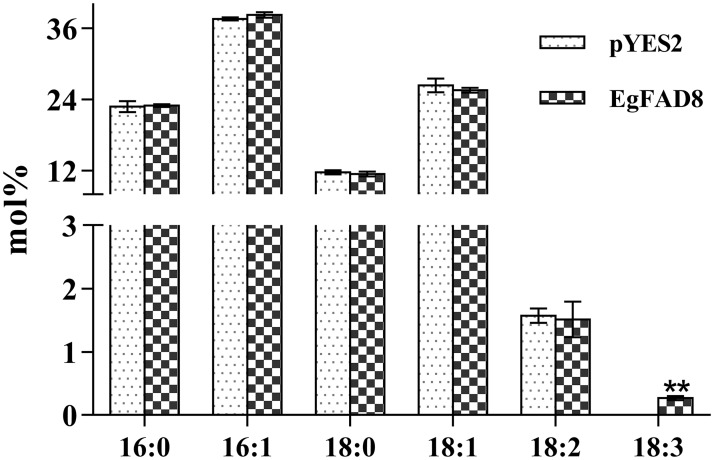

Heterologous expression of EgFAD8 in yeast could produce 18:3 using exogenous 18:2

The activity of EgFAD8 was determined by heterologous expression in S. cerevisiae supplemented with linoleic acid as substrate, which is absent in yeast. Yeast transformed with empty vector (pYES2) was used as negative control. The total fatty acid composition of yeast transformed with EgFAD8 or pYES2 was detected and analyzed. The result showed that yeast transformed with EgFAD8 produced a new fatty acid species 18:3 ω-3 (about 0.27 mol%) in yeast, but not presented in the negative control (Fig 3). Meanwhile, there was no obvious difference in the levels of other fatty acids between yeast transformed with EgFAD8 and the negative control pYES2 (Fig 3). Therefore, the expression of EgFAD8 in yeast could produce 18:3 using the supplemented 18:2.

Fig 3. Total fatty acid composition of transformed yeast with EgFAD8 or pYES2.

All experiments were carried out in triplicate. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with the control (Student’s t test: **, p < 0.01). 16:0, palmitic acid; 16:1, palmitoleic acid; 18:0, stearic acid; 18:1, oleic acid; 18:2, linoleic acid; 18:3,alpha linoleic acid.

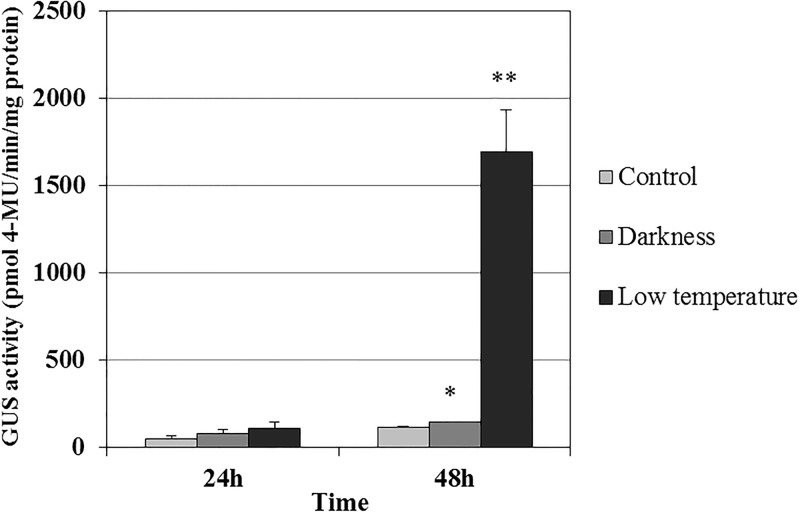

The activity of EgFAD8 promoter response to growth environment treatments

Promoter prediction analysis suggested that the EgFAD8 promoter contained some stress-responsive elements, including light-responsive elements. Therefore, further work was carried out to investigate whether it was induced under various stress conditions, such as cold and dark. The ProEgFAD8::GUS transgenic Arabidopsis T3 lines were cultivated at 15°C and in the dark, respectively, with other conditions are the same with the control. The GUS activity of transgenic plants under the darkness or low temperature treatment was no obvious difference with that of the control after 24 hours treatment (Fig 4). However, 48 hours treatment later, the GUS activity of the transgenic plants under the darkness treatment showed obvious increase by 26% when compared with that of the control, and the transgenic plants under the low temperature treatment exhibited the extraordinarily significant increase of GUS activity by about 14-fold comparing with the control (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Quantification of GUS activity in leaves of transgenic Arabidopsis transformed with ProEgFAD8::GUS under the treatment of darkness or low temperature (15°C) for 24h and 48h.

Discussion

In this study, we identified and characterized the first chloroplast ω-3 fatty acid desaturase (EgFAD8) from oil palm. It exhibited the capability of synthesizing 18:3 ω-3 when heterologously expressed in yeast with the exogenous supply of linoleic acid. However, there are three ω-3 fatty acid desaturases in Arabidopsis: the ER-localized FAD3 and two chloroplastic FAD7 and FAD8. When compared with fatty acid desaturases from Arabidopsis, EgFAD8 showed the highest similarity with the temperature-sensitive chloroplastic ω-3 fatty acid desaturase and AtFAD8 (data not shown). Moreover, the phylogenetic analysis of EgFAD8 revealed that it is grouped with AtFAD7 and AtFAD8 from Arabidopsis, but with more close relation with AtFAD8 (Fig 1). Therefore, the bioinformatic analysis of EgFAD8 indicated that the EgFAD8 gene might encode a plastidial FAD8, which could be induced by low temperature [16]. Nevertheless, more experimental evidence should be shown to support the results from sequence analysis although FAD8 sequences are highly conserved in plants [17].

Furthermore, the expression pattern in oil palm mesocarp at five developmental stages and leaves was also detected to see whether the expression level of EgFAD8 is correlated with oil deposition in oil palm mesocarp. While, we can see EgFAD8 was predominately expressed in leaves, at least twice-fold as that of mesocarp. Moreover, the expression level of EgFAD8 remains still during fruit ripening with a slight increase at the beginning. The majority of oil deposition in oil palm mesocarp occurs at the late stages (from phase 3 to phase 5) [32,35]. Thus, the expression of EgFAD8 is not correlated with oil accumulation in mesocarp. Similar patterns have been seen in the expression of FAD8 in other plant species [11,13,17]. The GmFAD8 genes from soybean were constitutively expressed in all vegetative tissues (roots, stems, mature leaves and flowers) analyzed at optimal growth temperatures [11,13]. Like EgFAD8, the plastidial PfrFAD7 genes from Perilla frutescens var. frutescens were expressed at low levels during all developmental stages of seeds, when compared with expression levels in leaves [17]. Therefore, this result is also another proof to support EgFAD8 encodes a plastidial ω-3 fatty acid desaturase, rather than the microsomal ω-3 fatty acid desaturase.

In order to study the in vivo function of EgFAD8, it has been successfully expressed in S. cerevisiae. However, there is no linoleic acid (18:2) produced in yeast. So the exogenous supply of 18:2 is needed for studying the activity of ω-3 fatty acid desaturase. The result from GC analysis indicated that the EgFAD8 transformed yeast cells could produce slight amounts of 18:3 using the exogenous 18:2. At least, this result confirmed the in vivo activity of ω-3 fatty acid desaturase encoded by EgFAD8 from oil palm. While, the amount of 18:3 produced by the EgFAD8 transformed yeast is very limited. There might be three possible reasons as follows: first, the EgFAD8 gene is likely to encode a chloroplast ω-3 fatty acid desaturase, rather than the ER-localized desaturase; thus it could not participate in the synthesis of storage oil in oil palm mesocarp. Likewise, when expressed in yeast cells, EgFAD8 might just be involved in the desaturation of galactolipids in the plastid. Second, EgFAD8 has been predicted to be temperature-sensitive desaturase by bioinformatic analysis. The yeast growth condition at 30 °C might not intrigue the large expression of transformed gene EgFAD8. Third, the exogenous supply of 18:2 might be a bit unhealthy or toxic for yeast cell. So, the coexpression of ω-3 fatty acid desaturase with ω-6 fatty acid desaturase in yeast might be a better solution than feeding with 18:2 in the yeast culture. However, the JcFAD7 from Jatropha curcas also showed the similar result when expressed in yeast, producing about 2.5% of 18:3 in transformed cells [24]. Therefore, the EgFAD8 gene from oil palm encodes a ω-3 fatty acid desaturase.

Furthermore, in order to elucidate the physiological role of EgFAD8, we also detected whether the EgFAD8 promoter could be affected by the environmental stress including low-temperature and darkness treatments. In our previous study, the activity of EgFAD8 promoter in transgenic Arabidopsis has been characterized (S1 Fig) [44]. The GUS staining results indicated that the EgFAD8 promoter has the expected capability to drive transgene expression in all tissues tested, except with very weak expression in roots (S1 Fig). Thus, we used the ProEgFAD8::GUS transgenic plants for the stress treatment analysis, since the EgFAD8 promoter is constitutively active in transgenic Arabidopsis. The results revealed that the GUS activity of the transgenic plants under the darkness and low temperature treatment was increased by 26% and 14-folds after 48-hour treatment when compared with that of the control, respectively (Fig 4). So the EgFAD8 gene from oil palm could be significantly induced by low temperature and slightly induced by darkness. This is consistent with the induction expression of AtFAD8 from Arabidopsis when treated at 4 °C [16,50]. Similarly, the PoleFAD8 transcript level of Portulaca oleracea L. also increased significantly after treatment at 5 °C [51]. As expected, this result also evidenced that the chloroplastic EgFAD8 from oil palm is cold-inducible. On the other hand, lots of light regulatory elements were predicted in the promoter of EgFAD8 by PlantCARE [44]. The result of the darkness treatment on transgenic plants is also consistent with the bioinformatic prediction. The darkness could slightly induce the expression of EgFAD8. While, the mechanism that the light regulates the expression of FAD8 still remains obscure. Our hypothesis is that more chloroplasts are needed for fatty acid synthesis in the dark than in the light, since the rate of fatty acid synthesis in leaves is six-fold higher in the light than in the dark [2]. Thus, to maintain the constitutive function, more chloroplasts are synthesized in the leave cells, and the expression level of genes encoding the corresponding enzymes involved in the synthesis of chloroplast might be up-regulated. FAD8 is responsible for the polyunsaturated components of chloroplast membranes [16]. However, the related mechanism needs to be elucidated.

In conclusion, we have isolated and identified a plastidial ω-3 fatty acid desaturase (EgFAD8) from oil palm. The in vivo function of EgFAD8 has been confirmed by heterologously expression in yeast, with showing the conversion of linoleic to linolenic acid. Moreover, the expression profile of EgFAD8 also revealed that it mainly involved in the synthesis of chloroplast membrane, unlike ER-localized ω-3 fatty acids that is tightly correlated with the oil accumulation in seeds or fruits [1,20,25]. Furthermore, the characterization of the EgFAD8 promoter indicated that the EgFAD8 gene could be induced by low temperature and darkness. Overall, these results will be helpful for understanding the function and regulation of plastidial ω-3 fatty acid desaturases in higher plants.

Supporting information

The results from transgenic Arabidopsis: A1-A5; the untransformed Arabidopsis were used as the negative control: B1-B5. 1: three-week-old seedling; 2: leaves; 3: roots; 4: flowers and stems; 5: silique coats.

(TIF)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (to DL: 31360476 and 31660222; to YZ: 31460213) and Hainan Natural Science Foundation(to LY: 20163138). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hernández ML, Sicardo MD, Martínez-Rivas JM. Differential Contribution of Endoplasmic Reticulum and Chloroplast ω-3 Fatty Acid Desaturase Genes to the Linolenic Acid Content of Olive (Olea europaea) Fruit. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57: 138–151. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohlrogge J, Browse J. Lipid Biosynthesis. PLANT CELL ONLINE. 1995;7: 957–970. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford MA. The role of essential fatty acids and prostaglandins. Postgrad Med J. 1980;56: 557–562. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.56.658.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damude HG, Zhang H, Farrall L, Ripp KG, Tomb J-F, Hollerbach D, et al. Identification of bifunctional Δ12/ω3 fatty acid desaturases for improving the ratio of ω3 to ω6 fatty acids in microbes and plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103: 9446–9451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511079103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker EJ, Miles EA, Burdge GC, Yaqoob P, Calder PC. Metabolism and functional effects of plant-derived omega-3 fatty acids in humans. Prog Lipid Res. 2016;64: 30–56. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calder PC. n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Inflammation : From Molecular Biology to the Clinic. Inflammation. 2003;38: 343–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon E, Bardet B, Grégoire S, Acar N, Bron AM, Creuzot-Garcher CP, et al. Decreasing dietary linoleic acid promotes long chain omega-3 fatty acid incorporation into rat retina and modifies gene expression. Exp Eye Res. 2011;93: 628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton ML, Haslam RP, Napier JA, Sayanova O. Metabolic engineering of Phaeodactylum tricornutum for the enhanced accumulation of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Metab Eng. Elsevier; 2014;22: 3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahidi F. Omega-3 fatty acids and marine oils in cardiovascular and general health: A critical overview of controversies and realities. J Funct Foods. 2015;19: 797–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.09.038 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Browse J, Somerville C. Glycerolipid Synthesis: Biochemistry and Regulation. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42: 467–506. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.42.060191.002343 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreu V, Lagunas B, Collados R, Picorel R, Alfonso M. The GmFAD7 gene family from soybean: Identification of novel genes and tissue-specific conformations of the FAD7 enzyme involved in desaturase activity. J Exp Bot. 2010;61: 3371–3384. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li-Beisson Y, Shorrosh B, Beisson F, Andersson MX, Arondel V, Bates PD, et al. Acyl-lipid metabolism. Arabidopsis Book. 2013;11: e0161 doi: 10.1199/tab.0161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Román, Chiappetta A, Bruno L, Bitonti MB. Contribution of the different omega-3 fatty acid desaturase methylation and chromatin patterning genes to the cold response in soybean. J Exp Bot. 2012;63: 695–709.22058406 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajwade A V., Kadoo NY, Borikar SP, Harsulkar AM, Ghorpade PB, Gupta VS. Differential transcriptional activity of SAD, FAD2 and FAD3 desaturase genes in developing seeds of linseed contributes to varietal variation in α-linolenic acid content. Phytochemistry. Elsevier Ltd; 2014;98: 41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy DJ, Piffanelli P. Fatty acid desaturases: structure, mechanism and regulation Plant lipid biosynthesis: fundamentals and agricultural applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson S, Arondel V, Iba K, Somerville C. Cloning of a temperature-regulated gene encoding a chloroplast omega-3 desaturase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1994;106: 1615–1621. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KR, Lee Y, Kim EH, Lee SB, Roh KH, Kim JB, et al. Functional identification of oleate 12-desaturase and ω-3 fatty acid desaturase genes from Perilla frutescens var. frutescens. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35: 2523–2537. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yadav NS, Wierzbicki A, Aegerter M, Caster CS, Pérez-Grau L, Kinney AJ, et al. Cloning of higher plant omega-3 fatty acid desaturases. Plant Physiol. 1993;103: 467–476. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.2.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iba K, Gibson S, Nishiuchis T, Fuse T, Nishimuras M, Arondelll V, et al. A gene encoding a chloroplast ω-3 fatty acid desaturase complements alterations in fatty acid desaturation and chloroplast copy number of the fad7 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 1993;268: 24099–24105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bilyeu KD, Palavalli L, Sleper DA, Beuselinck PR. Three microsomal omega-3 fatty-acid desaturase genes contribute to soybean linolenic acid levels. Crop Sci. 2003;43: 1833–1838. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2003.1833 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berberich T, Harada M, Sugawara K, Kodama H, Iba K, Kusano T. Two maize genes encoding ω-3 fatty acid desaturase and their differential expression to temperature. 1998; 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banilas G, Nikiforiadis A, Makariti I, Moressis A, Hatzopoulos P. Discrete roles of a microsomal linoleate desaturase gene in olive identified by spatiotemporal transcriptional analysis. Tree Physiol. 2007;27: 481–490. doi: 10.1093/treephys/27.4.481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guan L, Wu W, Hu B, Li D, Chen J, Hou K, et al. Devolopmental and growth temperature regulation of omega-3 fatty acid desaturase genes in safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.). 2014;13: 6623–6637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo L, Qing R, He W, Xu Y, Tang L, Wang S, et al. Identification and characterization of a plastidial ω3-fatty acid desaturase gene from Jatropha curcas. Chinese J Appl Environ Biol. 2008;14: 469–474. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vrinten P, Hu Z, Munchinsky M-A, Rowland G, Qiu X. Two FAD3 Desaturase Genes Control the Level of Linolenic Acid in Flax Seed. Plant Physiol. 2005;139: 79–87. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.064451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kodama H, Hamada T, Horiguchi G, Nishimura M, Iba K. Genetic Enhancement of Cold Tolerance by Expression of a Gene for Chloroplast [omega]-3 Fatty Acid Desaturase in Transgenic Tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1994;105: 601–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iba K. Acclimative response to temperature stress in higher plants: approaches of gene engineering for temperature tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53: 225–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100201.160729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dominguez T, Hernandez ML, Pennycooke JC, Jimenez P, Martinez-Rivas JM, Sanz C, et al. Increasing ω-3 Desaturase Expression in Tomato Results in Altered Aroma Profile and Enhanced Resistance to Cold Stress. Plant Physiol. 2010;153: 655–665. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.154815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Angeli S, Matteucci M, Fattorini L, Gismondi A, Ludovici M, Canini A, et al. OeFAD8, OeLIP and OeOSM expression and activity in cold-acclimation of Olea europaea, a perennial dicot without winter-dormancy. Planta. 2016;243: 1279–1296. doi: 10.1007/s00425-016-2490-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szymanski J, Brotman Y, Willmitzer L, Cuadros-Inostroza A. Linking Gene Expression and Membrane Lipid Composition of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2014;26: 915–928. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.118919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagunas B, Román Á, Andreu V, Picorel R, Alfonso M. A temporal regulatory mechanism controls the different contribution of endoplasmic reticulum and plastidial ω-3 desaturases to trienoic fatty acid content during leaf development in soybean (Glycine max cv Volania). Phytochemistry. 2013;95: 158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourgis F, Kilaru A, Cao X, Ngando-ebongue G-F, Drira N, Ohlrogge JB, et al. Comparative transcriptome and metabolite analysis of oil palm and date palm mesocarp that differ dramatically in carbon partitioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108: 12527–12532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106502108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bazmi AA, Zahedi G, Hashim H. Progress and challenges in utilization of palm oil biomass as fuel for decentralized electricity generation. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2011;15: 574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2010.09.031 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dislich C, Keyel AC, Salecker J, Kisel Y, Meyer KM, Auliya M, et al. A review of the ecosystem functions in oil palm plantations, using forests as a reference system. Biol Rev. 2016;49 doi: 10.1111/brv.12295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dussert S, Guerin C, Andersson M, Joet T, Tranbarger TJ, Pizot M, et al. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Three Oil Palm Fruit and Seed Tissues That Differ in Oil Content and Fatty Acid Composition. Plant Physiol. 2013;162: 1337–1358. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.220525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corley RHV, Tinker PB, editors. The Oil Palm [Internet]. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2003. doi: 10.1002/9780470750971 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ebong PE, Owu DU, Isong EU. Influence of palm oil (Elaesis guineensis) on health. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1999;53: 209–222. doi: 10.1023/A:1008089715153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun R, Gao L, Yu X, Zheng Y, Li D, Wang X. Identification of a Δ12 fatty acid desaturase from oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) involved in the biosynthesis of linoleic acid by heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. Elsevier B.V.; 2016;592: 21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin Y, Yuan Y, Gao L, Sun R, Chen L, Li D, et al. Characterization and Functional Analysis of a Type 2 Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase (DGAT2) Gene from Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) Mesocarp in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, Mcgettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23: 2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. Oxford University Press; 2011;28: 2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30: 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li D, Fan Y. Extraction and quality analysis of total RNA from pulp ofcoconut (Cocos nucifera L.). Mol Plant Breed (in Chinese). 2007;5: 883–886. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang L, Gao L, Zheng Y, Li D. Cloning and expression tissue-specific analiysis of fatty acid desaturase gene ω3 promoter from oil palm. Mol Plant Breed (in Chinese). 2016;14: 570–577. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH, Willems AR, Woods RA. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 1995;11: 355–360. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali Transformation of Intact Yeast Cells Treated with Alkali Cations. 1983;153: 166–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW. GUS fusions: beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 1987;6: 3901–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantiWcation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein—dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72: 248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001;25: 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kargiotidou A, Deli D, Galanopoulou D, Tsaftaris A, Farmaki T. Low temperature and light regulate delta 12 fatty acid desaturases (FAD2) at a transcriptional level in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). J Exp Bot. 2008;59: 2043–2056. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teixeira MC, Carvalho IS, Brodelius M. ω-3 Fatty acid desaturase genes isolated from purslane (portulaca oleracea L.): Expression in different tissues and response to cold and wound stress. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58: 1870–1877. doi: 10.1021/jf902684v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The results from transgenic Arabidopsis: A1-A5; the untransformed Arabidopsis were used as the negative control: B1-B5. 1: three-week-old seedling; 2: leaves; 3: roots; 4: flowers and stems; 5: silique coats.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.