Abstract

Phylogenetic comparative methods explore the relationships between quantitative traits adjusting for shared evolutionary history. This adjustment often occurs through a Brownian diffusion process along the branches of the phylogeny that generates model residuals or the traits themselves. For high-dimensional traits, inferring all pair-wise correlations within the multivariate diffusion is limiting. To circumvent this problem, we propose phylogenetic factor analysis (PFA) that assumes a small unknown number of independent evolutionary factors arise along the phylogeny and these factors generate clusters of dependent traits. Set in a Bayesian framework, PFA provides measures of uncertainty on the factor number and groupings, combines both continuous and discrete traits, integrates over missing measurements and incorporates phylogenetic uncertainty with the help of molecular sequences. We develop Gibbs samplers based on dynamic programming to estimate the PFA posterior distribution, over 3-fold faster than for multivariate diffusion and a further order-of-magnitude more efficiently in the presence of latent traits. We further propose a novel marginal likelihood estimator for previously impractical models with discrete data and find that PFA also provides a better fit than multivariate diffusion in evolutionary questions in columbine flower development, placental reproduction transitions and triggerfish fin morphometry.

Keywords: Bayesian inference, comparative methods, morphometrics, phylogenetics

Phylogenetic comparative methods revolve around uncovering relationships between different characteristics or traits of a set of organisms over the course of their evolution. One way to gain insight into these interactions is to analyze unadjusted correlations between traits across taxa. However, as insightfully noted by Felsenstein (1985), unadjusted analyses introduce the inherent challenge that any association uncovered may reflect the shared evolutionary history of the organisms being studied, and hence their similar traits values, rather than processes driving traits to covary over time. Thus, studies to identify covarying evolutionary trait processes must simultaneously adjust for shared evolutionary history.

There have been many attempts to accomplish this goal. Felsenstein (1985) and Ives and Garland (2010) are two such important examples, but they rely on a known evolutionary history described by a fixed phylogenetic tree and consider univariate evolutionary processes giving rise to only single traits. Felsenstein (1985) treats continuous traits as undergoing conditionally independent, Brownian diffusion down the branches of the phylogenetic tree and Ives and Garland (2010) posit a regression model where the tree determines the error structure in the univariate outcome model. Huelsenbeck and Rannala (2003) adapt the Brownian diffusion description in a Bayesian framework with the goal of drawing simultaneous inference on both the tree from molecular sequence data as well as the correlations of interest related to a small number of traits through a multivariate Brownian diffusion process. Lemey et al. (2010) extend the multivariate process by relaxing the strict Brownian assumption along distinct branches in the tree using a scale mixture of normals representation. Cybis et al. (2015) jointly model molecular sequence data and multiple traits using a multivariate latent liability formulation to combine both continuous and discrete observations and determine their correlation structure while adjusting for shared ancestry. This method is effective, but inference remains computationally expensive and estimates of the high-dimensional correlation matrix between traits only allows us to explain the evolution of these traits through a single process. Additional frequentist methods include, Revell (2009) who use a phylogenetically adjusted principal components analysis (PCA), Adams (2014) who use a phylogenetic least squares analysis, and Clavel et al. (2015) who also use a multivariate diffusion method. All of these methods, however require large matrix inversions which make them ill-suited to adaptations to full Bayesian inference, or bootstrapping to provide measures of uncertainty.

One way to alleviate these problems lies with dimension reduction through exploratory factor analysis (Aguilar and West 2000). Factor analysis is the inferred decomposition of observed data into two matrices, a factor matrix representing a set of underlying unobserved characteristics of the subject which give rise to the observed characteristics and a loadings matrix which explains the relationship between the unobserved and observed characteristics. Another form of dimension reduction through matrix decomposition is an eigen decomposition known as a PCA. Santos (2009) provides a method for constructing PCA adjusted for evolutionary history. This method, however, has the same problems typically associated with PCA, namely that it is not invariant to the scaling of the data and is not conducive to Bayesian analysis since it is not a likelihood based method. In a frequentist setting, the author also provides no approach for simultaneous inference on the phylogenetic tree that is rarely known without error (Huelsenbeck and Rannala 2003). In addition, there lacks a reasonable prescription for measuring uncertainty about which traits contribute to which principal components. Rai and Daume (2008) design a factor analysis method which uses a Kingman coalescent to construct a dendrogram across a factor analysis for genetic data. While this is similar to the idea we will employ, this specific method uses a dendrogram between, rather than within, factors and is thus ill suited to handle the important problem we tackle in this article. Namely, researchers often seek to identify a small number of relatively independent evolutionary processes, each represented by a factor changing over the tree, that ultimately give rise to a large number of observed, dependent traits. This paper provides such a dimension reduction tool by introducing phylogenetic factor analysis (PFA).

To formulate such a PFA model, we begin with usual Bayesian factor analysis, as posited by Lopes and West (2004) and Quinn (2004), which represents underlying latent characteristics of a group of organisms through a factor matrix and maps those latent characteristics to observed characteristics via a loadings matrix. In a standard factor analysis, the underlying factors for each species would be assumed to be independent of each other, however this does nothing to adjust for evolutionary history. Vrancken et al. (2015) describe how a high-dimensional Brownian diffusion can be used to describe the relationship between all of these observed traits, however the signal strength of the results of analyzing this model can be quite poor. By using independent Brownian diffusion priors on our factors, our PFA model groups traits into a parsimonious number of factors while successfully adjusting for phylogeny. Scientifically, these diffusions represent independent evolutionary processes. We use Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) integration in order to draw inference on our model through a Metropolis-within-Gibbs approach. This facilitates both a latent data representation (Cybis et al. 2015) for integrating discrete and continuous traits and a natural method to handle missing data relevant to our problems. We further rely on path sampling methods (Gelman and Meng 1998) to determine the appropriate number of factors (Ghosh and Dunson 2009). Since the latent, probit model necessitates the use of hard thresholds, we now have introduced an inherent difficulty in path sampling. In order to get around this difficulty, we employ a novel method which relies on softening the threshold necessitated by the probit model slowly over the course of the path. We additionally develop a novel method by which to handle identifiability issues inherent to factor analysis by taking advantage of the fact that correlated elements in the loadings matrix tend to be correlated across the MCMC chain.

We show that our PFA method performs superiorly to a high-dimensional Brownian diffusion in both model fit, specifically through Bayes factors, and, when we are inferring large numbers of latent traits, speed using the examples of the evolution of the flower genus Aquilegia, as well as the reproduction of the fish family Poeciliidae that involves trait measurements missing at random. Lastly, we explore the dorsal, anal and pectoral fin shapes of the fish family Balistidae in order to explore this method’s ability to handle situations where the number of traits are large compared with the number of species and to explore the simultaneous inference on our method along with the evolutionary history of these organisms with the aid of sequence data. The PFA model and its inference tools will be released in the popular phylogenetic inference package BEAST (Drummond et al. 2012).

Methods

Phenotypic Trait Evolution

Consider a collection of  biological entities (taxa). From each taxon

biological entities (taxa). From each taxon  , we observe a

, we observe a  -dimensional measurement

-dimensional measurement  of traits and, if available, a molecular sequence

of traits and, if available, a molecular sequence  . We organize these phenotypic traits into an

. We organize these phenotypic traits into an  matrix

matrix  and an aligned sequence matrix

and an aligned sequence matrix  . These taxa are related to each other through an evolutionary history

. These taxa are related to each other through an evolutionary history  , informed through

, informed through  , and we are interested in learning about the evolutionary processes along this history that give rise to observed traits

, and we are interested in learning about the evolutionary processes along this history that give rise to observed traits  . The history

. The history  consists of a tree topology

consists of a tree topology  and a series of branch lengths

and a series of branch lengths  . The tree topology is a bifurcating directed acyclic graph with a single generating point called the root, representing the most recent common ancestor of the given taxa, and with end points, each of which corresponds to a different taxon. The branch lengths correspond to edge weights of the graph, reflecting the evolutionary time before bifurcations. The history

. The tree topology is a bifurcating directed acyclic graph with a single generating point called the root, representing the most recent common ancestor of the given taxa, and with end points, each of which corresponds to a different taxon. The branch lengths correspond to edge weights of the graph, reflecting the evolutionary time before bifurcations. The history  may be known and fixed, or unknown and jointly inferred using

may be known and fixed, or unknown and jointly inferred using  and

and  . For further details on constructing the sequence-informed prior distribution

. For further details on constructing the sequence-informed prior distribution  and integrating over

and integrating over  when unknown (see, e.g., Suchard et al. 2001 or Drummond et al. 2012).

when unknown (see, e.g., Suchard et al. 2001 or Drummond et al. 2012).

In order to simultaneously model continuous, binary and ordinal traits, we adapt a latent data representation through the partially observed, standardized matrix  with entries

with entries

|

(1) |

where  is the mean of trait

is the mean of trait  across taxa,

across taxa,  is its standard deviation for

is its standard deviation for  and,more importantly,

and,more importantly,  is an unknown random variable that satisfies the restrictions

is an unknown random variable that satisfies the restrictions

|

(2) |

and  for

for  -valued binary/ordinal data for trait

-valued binary/ordinal data for trait  . For identifiability, latent trait cut-points

. For identifiability, latent trait cut-points  take on the restrictions

take on the restrictions  ,

,  and

and  or are otherwise random and jointly inferred. Grouping cut-points for all binary or ordinal traits into

or are otherwise random and jointly inferred. Grouping cut-points for all binary or ordinal traits into  , Cybis et al. (2015) suggest assuming that differences between the small number of successive, random cut-points are a priori exponentially distributed with mean

, Cybis et al. (2015) suggest assuming that differences between the small number of successive, random cut-points are a priori exponentially distributed with mean  to define their density

to define their density  . Cybis et al. (2015) also discuss in detail how to treat categorical data in this sort of analysis. Since we do not use examples which contain nonordered categorical data we elect not to describe those methods in these sections, but we will mention that they are implemented in BEAST and are easily adapted to fit the methods described in this article.

. Cybis et al. (2015) also discuss in detail how to treat categorical data in this sort of analysis. Since we do not use examples which contain nonordered categorical data we elect not to describe those methods in these sections, but we will mention that they are implemented in BEAST and are easily adapted to fit the methods described in this article.

In order to uncover the biological relationships amongst traits in  while controlling for evolutionary history, previous work relies on a Gaussian process generative model induced through considering conditionally independent Brownian diffusion along each branch in

while controlling for evolutionary history, previous work relies on a Gaussian process generative model induced through considering conditionally independent Brownian diffusion along each branch in  (Felsenstein 1985). In a multivariate setting, a

(Felsenstein 1985). In a multivariate setting, a  variance matrix

variance matrix  and unobserved,

and unobserved,  -dimensional root trait value

-dimensional root trait value  characterize the process. Pybus et al. (2012) identify that analytic integration of

characterize the process. Pybus et al. (2012) identify that analytic integration of  is possible by assuming that

is possible by assuming that  is a priori multivariate normally distributed with a fixed hyperprior mean

is a priori multivariate normally distributed with a fixed hyperprior mean  and variance equal to

and variance equal to  , where

, where  is a fixed hyperprior sample-size. Consequentially, given

is a fixed hyperprior sample-size. Consequentially, given  and

and  , the latent traits

, the latent traits  are distributed according to a matrix-normal (MN)

are distributed according to a matrix-normal (MN)

|

(3) |

where  is the across-taxa (row) variance and a deterministic function of phylogeny

is the across-taxa (row) variance and a deterministic function of phylogeny  ,

,  is the across-trait (column) variance, and

is the across-trait (column) variance, and  is a

is a  matrix of ones (Vrancken et al. 2015). Traits

matrix of ones (Vrancken et al. 2015). Traits  have density function

have density function

|

(4) |

where  is the trace operator and

is the trace operator and  is a

is a  -dimensional column vector of ones. Tree variance matrix

-dimensional column vector of ones. Tree variance matrix  contains diagonal elements that are equal to the sum of the adjusted branch lengths in

contains diagonal elements that are equal to the sum of the adjusted branch lengths in  between the root node and taxon

between the root node and taxon  , and off-diagonal elements

, and off-diagonal elements  that are equal to the sum of the adjusted branch lengths between the root node and the MRCA of taxa

that are equal to the sum of the adjusted branch lengths between the root node and the MRCA of taxa  and

and  , where the adjusted branch lengths represent a function of wall time and a branch rate accounting for variation in evolutionary rate over the course of the tree. For our diffusion model, we scale our tree such that from the root to the most recent tip we say that the process has undergone one diffusion unit.

, where the adjusted branch lengths represent a function of wall time and a branch rate accounting for variation in evolutionary rate over the course of the tree. For our diffusion model, we scale our tree such that from the root to the most recent tip we say that the process has undergone one diffusion unit.

Placing a conjugate prior distribution on  , such as

, such as  where

where  is the hyperprior degrees of freedom and

is the hyperprior degrees of freedom and  is the hyperprior belief on the structure of the inverse of the variance matrix

is the hyperprior belief on the structure of the inverse of the variance matrix  , enables inference about its posterior distribution, shedding light on how the evolution of these traits relate to each other. Such inference often requires repeated evaluation of density (4), especially when the phylogeny

, enables inference about its posterior distribution, shedding light on how the evolution of these traits relate to each other. Such inference often requires repeated evaluation of density (4), especially when the phylogeny  or variance

or variance  is random. This evaluation suggests a computational order

is random. This evaluation suggests a computational order  , arising from the inversion of the

, arising from the inversion of the  variance matrix

variance matrix  and

and  variance matrix

variance matrix  . One easily avoids the latter by parameterizing the model in terms of

. One easily avoids the latter by parameterizing the model in terms of  (Lemey et al. 2010). To address the former, Pybus et al. (2012) provide an

(Lemey et al. 2010). To address the former, Pybus et al. (2012) provide an  dynamic programming algorithm to evaluate (4) without inversion of the across-taxa variance matrix, similar to Freckleton (2012). This advance certainly makes for more tractable inference under these diffusion models as

dynamic programming algorithm to evaluate (4) without inversion of the across-taxa variance matrix, similar to Freckleton (2012). This advance certainly makes for more tractable inference under these diffusion models as  grows large, but the quadratic dependence on

grows large, but the quadratic dependence on  still hampers their use for high-dimensional traits. Inference can often be slow, taking as long as a day for problems with a dozen traits and about 30 taxa to mix properly (Cybis et al. 2015). Finally, direct inference on

still hampers their use for high-dimensional traits. Inference can often be slow, taking as long as a day for problems with a dozen traits and about 30 taxa to mix properly (Cybis et al. 2015). Finally, direct inference on  can often fail to produce a coherent and interpretable conclusion about the number of independent evolutionary processes generating the traits if the matrix cannot be reordered to form approximately separated blocks especially if the signal is too weak to produce many statistically significant cells.

can often fail to produce a coherent and interpretable conclusion about the number of independent evolutionary processes generating the traits if the matrix cannot be reordered to form approximately separated blocks especially if the signal is too weak to produce many statistically significant cells.

Factor Analysis

To infer potentially low dimensional evolutionary structure among traits, we rely on dimension reduction via a PFA. This model builds on the premise that a small, but unknown number  of a priori independent univariate Brownian diffusion processes along

of a priori independent univariate Brownian diffusion processes along  provides a more parsimonious description of the covariation in

provides a more parsimonious description of the covariation in  than a

than a  -dimensional multivariate diffusion. We parameterize the PFA in terms of an

-dimensional multivariate diffusion. We parameterize the PFA in terms of an  factor matrix

factor matrix  whose

whose  columns

columns  for

for  represent the unobserved independent realizations of univariate diffusion at each of the

represent the unobserved independent realizations of univariate diffusion at each of the  tips in

tips in  , a

, a  loadings matrix

loadings matrix  that relates the independent factor columns to

that relates the independent factor columns to  , and an

, and an  model error matrix

model error matrix  , such that

, such that

|

(5) |

To inject information about and control for shared evolutionary history  , we specify that

, we specify that

|

(6) |

where  is the identity matrix of appropriate dimension and the residual column precision

is the identity matrix of appropriate dimension and the residual column precision  is a diagonal matrix with entries

is a diagonal matrix with entries  . Lastly, since

. Lastly, since  is unknown, we place a reasonably conservative

is unknown, we place a reasonably conservative  prior on it, such that

prior on it, such that  .

.

To better appreciate the details of the PFA model, we briefly compare it to a typical Bayesian factor analysis. Typical factor analyses assume that all entries of  are independent and identically distributed (iid) as

are independent and identically distributed (iid) as  , normal random variables with mean

, normal random variables with mean  and variance

and variance  . In PFA, the shared evolutionary history

. In PFA, the shared evolutionary history  specifies the correlation structure within the

specifies the correlation structure within the  entries of column

entries of column  . Often, one refers to a given column as a “factor.” Across factors, the column variance remains

. Often, one refers to a given column as a “factor.” Across factors, the column variance remains  to reflect our assertion that the underlying evolutionary processes generating

to reflect our assertion that the underlying evolutionary processes generating  are independent of each other. Note that in this model the number of parameters undergoing Brownian Diffusion is assumed to be of dimension

are independent of each other. Note that in this model the number of parameters undergoing Brownian Diffusion is assumed to be of dimension  as opposed to of dimension

as opposed to of dimension  in the previous model.

in the previous model.

To complete model specification of the loadings  and residual error

and residual error  , we assume

, we assume

|

(7) |

otherwise  to preserve identifiability under the scale-free latent model for discrete traits. Here,

to preserve identifiability under the scale-free latent model for discrete traits. Here,  signifies a gamma distributed random variable with hyperparameter scale

signifies a gamma distributed random variable with hyperparameter scale  and rate

and rate  .

.

Without further restrictions on  , any factor analysis remains overspecified. For example, given an orthogonal

, any factor analysis remains overspecified. For example, given an orthogonal  matrix

matrix  , one may rotate

, one may rotate  in one direction and

in one direction and  in the other and arrive at the same data likelihood, since

in the other and arrive at the same data likelihood, since  . To address this identifiability issue, we fix lower triangular entries

. To address this identifiability issue, we fix lower triangular entries  for

for  (Geweke and Zhou 1996; Aguilar and West 2000). It is also standard practice to apply the restriction

(Geweke and Zhou 1996; Aguilar and West 2000). It is also standard practice to apply the restriction  , since otherwise

, since otherwise  . While the constraint yields an identifiable posterior distribution with respect to

. While the constraint yields an identifiable posterior distribution with respect to  and

and  , we do not pursue it here because it introduces bias into our scientific inference on

, we do not pursue it here because it introduces bias into our scientific inference on  and, instead, search for an alternative.

and, instead, search for an alternative.

The diagonal and upper triangular entries  for

for  of the loadings

of the loadings  inform the magnitude and effect-direction that the evolutionary process captured in factor

inform the magnitude and effect-direction that the evolutionary process captured in factor  contributes to trait

contributes to trait  . As a quantitative measure of uncertainty about these relationships, we define

. As a quantitative measure of uncertainty about these relationships, we define  to equal the absolute difference between the posterior probability that

to equal the absolute difference between the posterior probability that  and the posterior probability that

and the posterior probability that  ; this measure ranges from

; this measure ranges from  when

when  is centered around

is centered around  to

to  when

when  is either strictly positive or strictly negative with probability

is either strictly positive or strictly negative with probability  . It is possible, and we would argue likely, that

. It is possible, and we would argue likely, that  has little or no influence on the trait arbitrarily labeled

has little or no influence on the trait arbitrarily labeled  , such that most of the posterior mass of

, such that most of the posterior mass of  lies around and close to

lies around and close to  . Artificially restricting

. Artificially restricting  forces all of this mass above

forces all of this mass above  , signifying a positive association with prior, and hence posterior, probability

, signifying a positive association with prior, and hence posterior, probability  .

.

To combat this bias, we recouch these identifiability conditions as a label switching problem in a mixture model and propose a post hoc relabeling algorithm (Stephens 2000). We require  sign constraints, one for each column-row outer-product in forming

sign constraints, one for each column-row outer-product in forming  , for posterior identification. In our prior, we modify equation (7) to further assign one nonzero entry

, for posterior identification. In our prior, we modify equation (7) to further assign one nonzero entry  per row, but do not specify which one; this assignment mirrors the mixture model labeling. Hence, we allow the data, not an arbitrary decision, to determine which entry per row reflects a positive association with probability

per row, but do not specify which one; this assignment mirrors the mixture model labeling. Hence, we allow the data, not an arbitrary decision, to determine which entry per row reflects a positive association with probability  , decreasing potential bias.

, decreasing potential bias.

Recalling that continuous traits are standardized in  to have mean

to have mean  and variance

and variance  affords several benefits. First, we can posit a

affords several benefits. First, we can posit a  -matrix mean for

-matrix mean for  in equation (6) without loss of information. But, more importantly, when we draw inference on

in equation (6) without loss of information. But, more importantly, when we draw inference on  , we can interpret traits which have precision elements that demonstrate considerable posterior mass at or below 1 to be described insufficiently by the model, since the factors provide no insight beyond a random normal model. A third advantage is that standardization helps us select reasonable scales for the nonzero entries in

, we can interpret traits which have precision elements that demonstrate considerable posterior mass at or below 1 to be described insufficiently by the model, since the factors provide no insight beyond a random normal model. A third advantage is that standardization helps us select reasonable scales for the nonzero entries in  , namely that these have variance

, namely that these have variance  , and hyperparameters for

, and hyperparameters for  , specifically that

, specifically that  . In practice,

. In practice,  and

and  for analyses in this paper. While these hyperparameter choices are by no means perfect we feel that, under the paradigm of data scaling, they are reasonable and generalizable across a variety of problems.

for analyses in this paper. While these hyperparameter choices are by no means perfect we feel that, under the paradigm of data scaling, they are reasonable and generalizable across a variety of problems.

This model is a simplified form of the item factor analysis models that are described by Quinn (2004) in the political science literature and Beguin and Glas (2001) in the psychology literature with a tree as a prior on the factors instead of an independent normal distribution. In fact, the methods for treating binary and ordinal data described in Quinn (2004) are the same as those described in Cybis et al. (2015), making for a convenient adaptation of this factor analysis model to phylogenetics using existing software in BEAST.

Inference

Given the trait measurements  and aligned sequences

and aligned sequences  , we strive to learn about the joint posterior distribution of the number of evolutionary processes

, we strive to learn about the joint posterior distribution of the number of evolutionary processes  , factors

, factors  , loadings

, loadings  , column precisions

, column precisions  , latent trait cut-points

, latent trait cut-points  and evolutionary history

and evolutionary history

|

(8) |

where  is the indicator function that the restrictions in Equation (2) hold. We accomplish this inference through MCMC, using a random-scan Metropolis-within-Gibbs scheme (Liu et al. 1995) for fixed

is the indicator function that the restrictions in Equation (2) hold. We accomplish this inference through MCMC, using a random-scan Metropolis-within-Gibbs scheme (Liu et al. 1995) for fixed  and a modification of path sampling to then estimate the marginal posterior

and a modification of path sampling to then estimate the marginal posterior  . For fixed

. For fixed  , our Metropolis-within-Gibbs scheme employs transition kernels described in Cybis et al. (2015) and references therein to integrate over the evolutionary history

, our Metropolis-within-Gibbs scheme employs transition kernels described in Cybis et al. (2015) and references therein to integrate over the evolutionary history  and unobserved, latent traits

and unobserved, latent traits  and cut-points

and cut-points  where trait

where trait  is discrete.

is discrete.

Here, we focus on transition kernels within the scheme to integrate over the factors  , loadings

, loadings  and residual column precision

and residual column precision  . Lopes and West (2004) derive full conditional distributions for the columns of

. Lopes and West (2004) derive full conditional distributions for the columns of  and diagonals of

and diagonals of  under a traditional factor analysis. These full conditional distributions do not change under a PFA and we use them for Gibbs sampling. Specifically, for column

under a traditional factor analysis. These full conditional distributions do not change under a PFA and we use them for Gibbs sampling. Specifically, for column  of

of  , the first

, the first  entries are nonzero and, given all other random variables, distributed according to a multivariate normal (MVN)

entries are nonzero and, given all other random variables, distributed according to a multivariate normal (MVN)

|

(9) |

parameterized in terms of its mean

|

(10) |

and variance

|

(11) |

where  is the first

is the first  columns of

columns of  and

and  is the unit-vector in the direction of trait

is the unit-vector in the direction of trait  . Further,

. Further,

|

(12) |

if trait  is continuous. The Appendix provides derivations of these full conditional distributions. Gibbs sampling all columns of

is continuous. The Appendix provides derivations of these full conditional distributions. Gibbs sampling all columns of  carries a computation order

carries a computation order  , arising from the matrix multiplication of

, arising from the matrix multiplication of  for each trait. The matrix inversion is not rate-limiting here since

for each trait. The matrix inversion is not rate-limiting here since  . Likewise, Gibbs sampling

. Likewise, Gibbs sampling  remains very light-weight at

remains very light-weight at  , stemming from the sparse multiplication of

, stemming from the sparse multiplication of  for each trait. While we write that the order of both Gibbs samplers depend on

for each trait. While we write that the order of both Gibbs samplers depend on  to be clear that we must iterate over all traits, the astute reader has already recognized the conditional independence of updates between traits, such that we may execute updates for each trait in parallel.

to be clear that we must iterate over all traits, the astute reader has already recognized the conditional independence of updates between traits, such that we may execute updates for each trait in parallel.

The traditional Gibbs sampler for  fails in the phylogenetic setting for more than a handful of taxa, since determining the full conditional distribution of

fails in the phylogenetic setting for more than a handful of taxa, since determining the full conditional distribution of  requires inverting the matrix

requires inverting the matrix  . As mentioned previously, but worth repeating, this task stands as prohibitive with a computational order

. As mentioned previously, but worth repeating, this task stands as prohibitive with a computational order  and presents a major challenge for PFA.

and presents a major challenge for PFA.

We circumvent this difficulty by exploiting the structure of the phylogenetic tree  . Probability models on directed, acyclic graphs lend themselves well to dynamic programming for determining marginalized data likelihoods, such as Felsenstein’s pruning algorithm for sequence data (Felsenstein 1973) and related work for Brownian diffusion (Pybus et al. 2012), and conditional predictive distributions, like those obtained for (ancestral) sequence reconstruction.

. Probability models on directed, acyclic graphs lend themselves well to dynamic programming for determining marginalized data likelihoods, such as Felsenstein’s pruning algorithm for sequence data (Felsenstein 1973) and related work for Brownian diffusion (Pybus et al. 2012), and conditional predictive distributions, like those obtained for (ancestral) sequence reconstruction.

In extending these conditional distributions to Brownian diffusion, first let  identify row

identify row  of

of  , more specifically all latent factor values attributed to taxon

, more specifically all latent factor values attributed to taxon  , and let

, and let  concatenate the remaining rows. Given that

concatenate the remaining rows. Given that  is matrix-normally distributed with an across-taxa (row) variance that depends on the phylogeny

is matrix-normally distributed with an across-taxa (row) variance that depends on the phylogeny  , Cybis et al. (2015) provide a tree-traversal-based algorithm to determine

, Cybis et al. (2015) provide a tree-traversal-based algorithm to determine  that remains a multivariate normal distribution. The algorithm requires first a post-order tree-traversal to determine the joint distribution of all tip-values descendent to each internal node and then a preorder tree-traversal back to taxon

that remains a multivariate normal distribution. The algorithm requires first a post-order tree-traversal to determine the joint distribution of all tip-values descendent to each internal node and then a preorder tree-traversal back to taxon  to compute its prior conditional mean

to compute its prior conditional mean  and precision

and precision  . Since the across-factor (column) variance on

. Since the across-factor (column) variance on  is diagonal, the dynamic programming algorithm runs quickly in

is diagonal, the dynamic programming algorithm runs quickly in  . Using this result, we determine the full conditional distribution

. Using this result, we determine the full conditional distribution

|

(13) |

with mean

|

(14) |

and variance

|

(15) |

where  is the unit-vector in the direction of taxon

is the unit-vector in the direction of taxon  . The Appendix delivers a derivation of this full conditional distribution. The evaluation of this full conditional distribution runs in

. The Appendix delivers a derivation of this full conditional distribution. The evaluation of this full conditional distribution runs in  where the term

where the term  is rate limiting.

is rate limiting.

Employing equations (13–15), we can cycle over  to fabricate a tractable Gibbs sampler for

to fabricate a tractable Gibbs sampler for  with total computational order

with total computational order  . It is fruitful to compare this work with the rate-limiting step for inference under the nonsparse model. Here, sampling the precision matrix

. It is fruitful to compare this work with the rate-limiting step for inference under the nonsparse model. Here, sampling the precision matrix  carries a computational cost of

carries a computational cost of  . From these bounds, it is clear that increasing numbers of taxa

. From these bounds, it is clear that increasing numbers of taxa  should limit PFA, while increasing numbers of traits

should limit PFA, while increasing numbers of traits  should limit the nonsparse model from a computational work per MCMC iteration perspective. However, per-iterative arguments ignore the posterior correlation between model parameters and its influence on MCMC mixing times.

should limit the nonsparse model from a computational work per MCMC iteration perspective. However, per-iterative arguments ignore the posterior correlation between model parameters and its influence on MCMC mixing times.

Finally, to maintain identifiability with respect to  and

and  in the posterior, we propose a simple post hoc relabeling algorithm (Stephens 2000). We sample

in the posterior, we propose a simple post hoc relabeling algorithm (Stephens 2000). We sample  from

from  for MCMC iteration

for MCMC iteration  assuming a sign-unconstrained prior. From this unconstrained sample, we select for each row

assuming a sign-unconstrained prior. From this unconstrained sample, we select for each row  in

in  the column element with the fewest number of sign changes between iterations. Assume for row

the column element with the fewest number of sign changes between iterations. Assume for row  , this is column

, this is column  . We then constrain our sample by multiplying

. We then constrain our sample by multiplying  and row

and row  of

of  by the sign of

by the sign of  . No further sample reweighing is necessary because

. No further sample reweighing is necessary because  is also invariant to reflection.

is also invariant to reflection.

Model selection.—

To estimate the marginal posterior density  , we rely on a variant of path sampling that we equip to successfully integrate latent variable

, we rely on a variant of path sampling that we equip to successfully integrate latent variable  when traits are discrete. We employ our variant to approximate each marginal likelihood

when traits are discrete. We employ our variant to approximate each marginal likelihood  for

for  , where

, where  is a relatively small number such as

is a relatively small number such as  , after which we approximate

, after which we approximate  . Then, invoking Bayes theorem,

. Then, invoking Bayes theorem,  . Moreover, through this approach, we can address the model selection problem of how many independent factors do the data support through Bayes factors (Jeffreys 1935):

. Moreover, through this approach, we can address the model selection problem of how many independent factors do the data support through Bayes factors (Jeffreys 1935):

|

(16) |

Lopes and West (2004) and Ghosh and Dunson (2009) have been strong proponents of Bayes factors to determine the optimal number of factors in a traditional factor analysis, where Lopes and West (2004) employ a simple harmonic mean estimator (Newton and Raftery 1994) to estimate their marginal likelihoods. This estimator performs poorly in highly structured phylogenetic models and path sampling has largely supplanted it (Baele et al. 2012).

Path sampling is an MCMC-based integration technique to estimate marginal likelihoods, such as  . The technique constructs a series of power posteriors (Friel and Pettitt 2008) at various temperatures

. The technique constructs a series of power posteriors (Friel and Pettitt 2008) at various temperatures  , where

, where  corresponds to a joint density

corresponds to a joint density  proportional, but with an unknown constant, to

proportional, but with an unknown constant, to  and

and  yields a normalized density

yields a normalized density  that does not depend on the data, often a combination of the prior and other working distributions (see e.g., Baele et al. 2016). The usual power posterior path is

that does not depend on the data, often a combination of the prior and other working distributions (see e.g., Baele et al. 2016). The usual power posterior path is  , where

, where  is the set of all parameters in the model we are considering. For example, in PFA,

is the set of all parameters in the model we are considering. For example, in PFA,

In latent models with discrete traits, however, the support of the latent variable  changes when the data are observed (Heaps et al. 2014). In particular, our unnormalized joint density

changes when the data are observed (Heaps et al. 2014). In particular, our unnormalized joint density  is zero for values of

is zero for values of  that are incompatible with

that are incompatible with  because

because  , therefore a trait

, therefore a trait  only has support over

only has support over  if

if  , while

, while  places nonzero density over all possible values

places nonzero density over all possible values  . Our working distribution, for example, assumes

. Our working distribution, for example, assumes  when

when  is random. If we factor

is random. If we factor  into a support condition

into a support condition  and the remaining likelihood

and the remaining likelihood  , then the standard path used in this scenario (Heaps et al. 2014) is

, then the standard path used in this scenario (Heaps et al. 2014) is

|

(17) |

For the power posterior method to yield the marginal likelihood  it is necessary (Friel and Pettitt 2008) that

it is necessary (Friel and Pettitt 2008) that

|

(18) |

Plugging (17) into (18), we find

|

(19) |

If we define  as the region where

as the region where  then we see that

then we see that

|

(20) |

since  the support of

the support of  While it is theoretically possible to construct

While it is theoretically possible to construct  such that it is normalized to 1 over

such that it is normalized to 1 over  , previous attempts to do so have failed. Alternatively, Heaps et al. (2014) attempt to approximate such a distribution by fixing

, previous attempts to do so have failed. Alternatively, Heaps et al. (2014) attempt to approximate such a distribution by fixing  and ignoring the corresponding integral.

and ignoring the corresponding integral.

We posit an exact solution by proposing a new path that relies on a softening threshold. Consider the modified path

|

(21) |

Following from (18), we find that

|

(22) |

by construction.

Lastly, in order to adapt the power posterior method, at each step in the series we need to compute the derivative of  with respect to

with respect to  . From equation (21), we see that

. From equation (21), we see that

|

(23) |

and observe that there is no singularity at  since, at that point in the path, latent variable

since, at that point in the path, latent variable  only assumes values in

only assumes values in  , such that

, such that  .

.

Empirical Examples

Columbine Flower Development

Columbine genus Aquilegia flowers have attracted at least three different pollinators across their evolutionary history: bumblebees (Bb), hawkmoths (Hm), and hummingbirds (Hb). Whittall and Hodges (2007) question the role that these pollinators play in the tempo of columbine flower evolution, tracked through the color, length and orientation of different anatomical floral features, and are particularly interested in how transitions between pollinators relate to spur length. Cybis et al. (2015) take up this question by examining  different traits for

different traits for  monophyletic populations from the genus Aquilegia that include

monophyletic populations from the genus Aquilegia that include  continuously valued traits, a binary trait that indicates presence or absence of anthocyanin pigment and a final ordinal trait indicating the primary pollinator for that population. Whittall and Hodges (2007) propose a Bb–Hm–Hb ordering and we use the fixed phylogenetic tree the authors employ in their analysis. Through fitting a latent multivariate Brownian diffusion (LMBD) model parameterized in terms of a

continuously valued traits, a binary trait that indicates presence or absence of anthocyanin pigment and a final ordinal trait indicating the primary pollinator for that population. Whittall and Hodges (2007) propose a Bb–Hm–Hb ordering and we use the fixed phylogenetic tree the authors employ in their analysis. Through fitting a latent multivariate Brownian diffusion (LMBD) model parameterized in terms of a  variance matrix

variance matrix  , Cybis et al. (2015) find the data strongly support the proposed ordering over alternative orderings. We return to the relationship between pollinator and the other traits and test whether a PFA returns a better understanding of the evolutionary factors driving their interrelated change compared with an LMBD model.

, Cybis et al. (2015) find the data strongly support the proposed ordering over alternative orderings. We return to the relationship between pollinator and the other traits and test whether a PFA returns a better understanding of the evolutionary factors driving their interrelated change compared with an LMBD model.

Under our PFA, the most probable number of independent evolutionary processes is  , with a log Bayes factor

, with a log Bayes factor  over the neighboring

over the neighboring  or

or  factor parameterizations (Table 1). Further, the PFA with

factor parameterizations (Table 1). Further, the PFA with  is favored over the LMBD model with a log Bayes factor

is favored over the LMBD model with a log Bayes factor  when assuming equal prior probabilities over these two models.

when assuming equal prior probabilities over these two models.

Table 1.

Log marginal likelihood estimates for the number  of independent factors driving evolution under a PFA and a LMBD model in Aquilegia, and Poeciliidae and MBD in Balistidae

of independent factors driving evolution under a PFA and a LMBD model in Aquilegia, and Poeciliidae and MBD in Balistidae

| Model | Log marginal likelihood | |

|---|---|---|

| Aquilegia |

|

–385.4 |

|

–366.9 | |

|

–374.3 | |

| LMBD | –391.1 | |

|

–536.0 | |

| Poeciliidae |

|

–500.7 |

|

–501.0 | |

|

–505.9 | |

| LMBD | –592.3 | |

| Balistidae |

|

–15622.0 |

|

–15603.5 | |

|

–15610.4 | |

| MBD | –15673.2 |

Notes: The  model for Aquilegia, the

model for Aquilegia, the  and

and  model for Poeciliidae and the

model for Poeciliidae and the  model for Balistidae achieve the highest marginal likelihoods.

model for Balistidae achieve the highest marginal likelihoods.

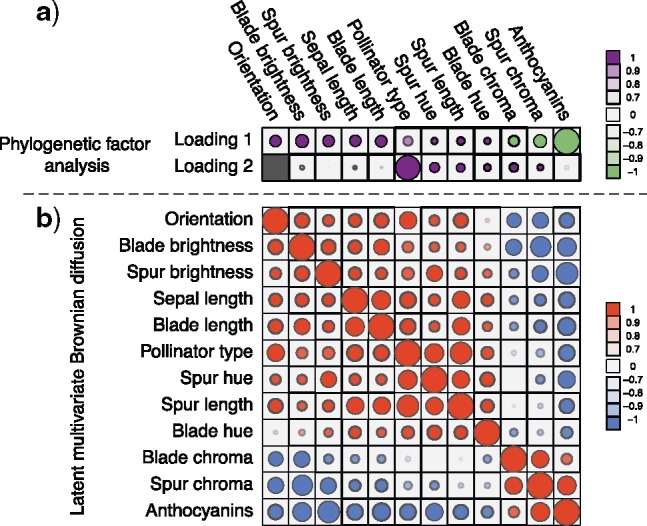

The PFA has high explanatory power for all continuous traits (Table 2) and Figure 1 presents our inference on the relationships between traits under the PFA with  and compares these findings to inference under the LMBD model. The first evolutionary process

and compares these findings to inference under the LMBD model. The first evolutionary process  approximately partitions the traits into two groups. One group includes: orientation, blade brightness, spur brightness, sepal length, blade length, pollinator type, spur hue, spur length, blade hue, and expected trait values increase (displayed loadings entries

approximately partitions the traits into two groups. One group includes: orientation, blade brightness, spur brightness, sepal length, blade length, pollinator type, spur hue, spur length, blade hue, and expected trait values increase (displayed loadings entries  in purple) as the factor grows over the phylogeny. The other group includes: blade chroma, anthocyanins pigment presence and, with less posterior probability, spur chroma, and expected trait values decrease (green) as the factor grows. A possible exception to the

in purple) as the factor grows over the phylogeny. The other group includes: blade chroma, anthocyanins pigment presence and, with less posterior probability, spur chroma, and expected trait values decrease (green) as the factor grows. A possible exception to the  partitioning is the pollinator trait, where we estimate only a 0.92 absolute difference in posterior probability of being greater than 0 versus less than 0.

partitioning is the pollinator trait, where we estimate only a 0.92 absolute difference in posterior probability of being greater than 0 versus less than 0.

Table 2.

Precision  posterior mean and 95% Bayesian credible interval estimates under the latent factor model for the traits in Aquilegia, in Poeciliidae and in Balistidae

posterior mean and 95% Bayesian credible interval estimates under the latent factor model for the traits in Aquilegia, in Poeciliidae and in Balistidae

| Trait | Posterior mean | 95% Bayesian credible interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation | 2.1 | [1.0, 3.3] | |

| Spur length | 4.4 | [2.0, 7.1] | |

| Blade length | 3.0 | [1.4, 4.8] | |

| Aquilegia | Sepal length | 2.6 | [1.3, 4.1] |

| Spur chroma | 4.2 | [1.8, 6.9] | |

| Spur hue | 6.2 | [2.6, 10.5] | |

| Spur brightness | 2.7 | [1.2, 4.3] | |

| Blade chroma | 2.3 | [1.1, 3.7] | |

| Blade hue | 2.1 | [1.0, 3.2] | |

| Blade brightness | 3.3 | [1.4, 0.6] | |

| Matrotrophy index | 14.3 | [5.6, 23.2] | |

Poeciliidae ( ) )

|

Gonopodium length | 9.3 | [4.3, 16.1] |

| Male body length | 3.5 | [2.4, 4.6] | |

| Male body weight | 2.8 | [1.9, 3.7] | |

| Female body length | 10.5 | [5.7, 15.5] | |

| Female body weight | 15.1 | [8.0, 24.3] | |

| Matrotrophy index | 13.8 | [5.5, 22.7] | |

Poeciliidae ( ) )

|

Gonopodium length | 9.1 | [4.4, 15.5] |

| Male body length | 3.5 | [2.3, 4.8] | |

| Male body weight | 2.8 | [1.9, 3.8] | |

| Female body length | 10.5 | [5.8, 15.5] | |

| Female body weight | 14.7 | [8.2, 22.5] |

Notes: The PFA model explains all of the continuous traits in these models better than a  distribution on the standardized traits.

distribution on the standardized traits.

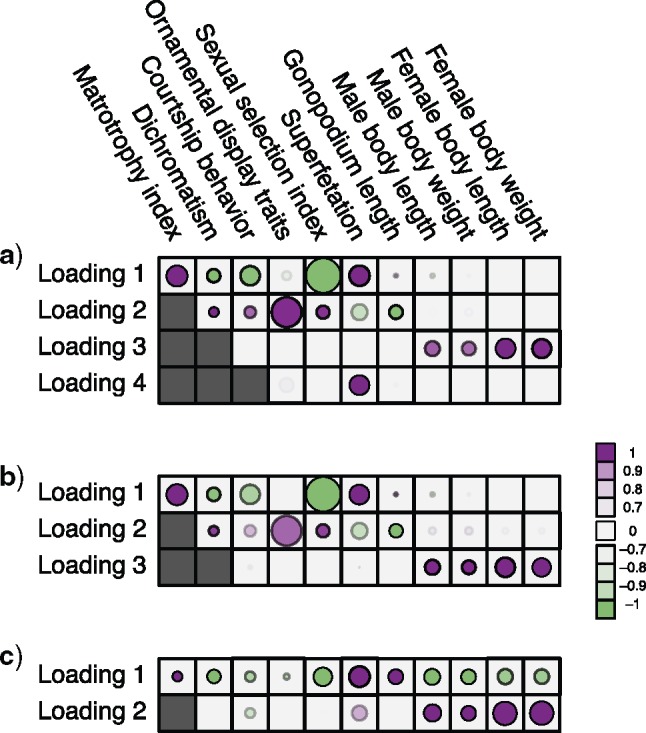

Figure 1.

Processes driving columbine flower evolution inferred through PFA or LMBD. a) Loadings  estimates from a

estimates from a  factor PFA model. Purple circles represent traits positively associated with traits represented by other purple circles within a loading, and negatively associated with traits represented by green circles within a loading. Similarly, traits represented by green circles are positively associated with traits represented by green circles within a loading. Size represents the magnitude of the value of the loadings. Opacity represents the posterior probability that the sign of the given element is equal to the sign of the posterior mean. The greyed out cell represents a structural 0 introduced for identifiability reasons. The magnitude for anthocyanins and pollinator type is less relevant since those measurements are discrete. b) Correlation matrix estimate from a LMBD model. Red represents positive correlation, blue represents anticorrelation, and opacity represents the absolute difference in posterior probability of being greater than 0 and less than 0. Size of the circle represents the magnitude of the correlation. The PFA captures well two independent processes, while the LMBD groups these processes together.

factor PFA model. Purple circles represent traits positively associated with traits represented by other purple circles within a loading, and negatively associated with traits represented by green circles within a loading. Similarly, traits represented by green circles are positively associated with traits represented by green circles within a loading. Size represents the magnitude of the value of the loadings. Opacity represents the posterior probability that the sign of the given element is equal to the sign of the posterior mean. The greyed out cell represents a structural 0 introduced for identifiability reasons. The magnitude for anthocyanins and pollinator type is less relevant since those measurements are discrete. b) Correlation matrix estimate from a LMBD model. Red represents positive correlation, blue represents anticorrelation, and opacity represents the absolute difference in posterior probability of being greater than 0 and less than 0. Size of the circle represents the magnitude of the correlation. The PFA captures well two independent processes, while the LMBD groups these processes together.

Ignoring the uncertainty in pollinator trait inclusion for the moment, this partitioning recapitulates the block structure that Cybis et al. (2015) report using an LMBD model and an arbitrary thresholding on the posterior mean estimates of the individual pairwise correlation entries in  . However, in Figure 1 we quantify the LMBD uncertainty by shading our inference using the same probability measure as we do for our PFA model. Taking correlation uncertainty into consideration we see that, for example the LMBD model would assert that there is no correlation between blade chroma and spur hue. The PFA model by contrast offers the more nuanced assessment that these traits are related through two independent underlying processes, one process of which has a positive association between these traits, the other of which has a negative association.

. However, in Figure 1 we quantify the LMBD uncertainty by shading our inference using the same probability measure as we do for our PFA model. Taking correlation uncertainty into consideration we see that, for example the LMBD model would assert that there is no correlation between blade chroma and spur hue. The PFA model by contrast offers the more nuanced assessment that these traits are related through two independent underlying processes, one process of which has a positive association between these traits, the other of which has a negative association.

In addition to improved uncertainty quantification in the block structure of traits, our PFA returns a second independent evolutionary process  that relates pollinator with spur length and, in addition, spur and blade chroma and hue, with posterior probability approaching

that relates pollinator with spur length and, in addition, spur and blade chroma and hue, with posterior probability approaching  . The existence of two distinct processes, one of which directly connects pollinator and spur length, sheds additional insight into the original hypothesis that Whittall and Hodges (2007) pose. The LMBD model fails to pick up on this, in addition to returning a worse fit to the data.

. The existence of two distinct processes, one of which directly connects pollinator and spur length, sheds additional insight into the original hypothesis that Whittall and Hodges (2007) pose. The LMBD model fails to pick up on this, in addition to returning a worse fit to the data.

Transitions to Placental Reproduction

The freshwater fish Poeciliidae represent a family of model organisms in which one can study the transition from nonplacental to placental reproduction and the evolutionary pressures associated with placental introduction. Pollux et al. (2014) define a matrotrophy index to be the log-ratio of the dry weight of newborn fish to the dry weight of eggs at fertilization as a proxy measure of how reliant a fish species is on its placenta for reproduction. Using phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) (Ives and Garland 2010), Pollux et al. (2014) find that Poeciliidae dichromatism, courtship behavior, superfetation, and a sexual selection index are all correlated over evolutionary history with the matrotrophy index. Unlike PFA, PGLS as used by Pollux et al. (2014) does not adjust for potential evolutionary relationships between the traits. Failure to do so can lead to false positive measures of association between individual traits and the matrotrophy index.

Pollux et al. (2014) collect from the literature or measure 14 life-history traits and compile from GenBank or sequence 28 different genes across Poeciliidae species. In our analysis, we only use  traits since three of the original traits are functions of the included ones. Of these traits, five are discrete-valued: dimorphic coloration (dichromatism), courtship behavior, superfetation, the presence or absence of ornamental display traits and a count composite of the presence or absence of three other male behaviors (sexual selection index). Six are continuous-valued: log weight and log length for males and females, gonopodium length, and matrotrophy index. Considering species with at least one trait measurement, there are

traits since three of the original traits are functions of the included ones. Of these traits, five are discrete-valued: dimorphic coloration (dichromatism), courtship behavior, superfetation, the presence or absence of ornamental display traits and a count composite of the presence or absence of three other male behaviors (sexual selection index). Six are continuous-valued: log weight and log length for males and females, gonopodium length, and matrotrophy index. Considering species with at least one trait measurement, there are  taxa, for which we assume the same fixed phylogenetic tree that Pollux et al. (2014) estimate and similarly condition on in their PGLS analysis. Importantly, 182 trait measurements remain missing. We treat these measurements as missing-at-random in our PFA and do not need to further prune the tree or impute values that may further introduce bias.

taxa, for which we assume the same fixed phylogenetic tree that Pollux et al. (2014) estimate and similarly condition on in their PGLS analysis. Importantly, 182 trait measurements remain missing. We treat these measurements as missing-at-random in our PFA and do not need to further prune the tree or impute values that may further introduce bias.

Pollux et al. (2014) find that dichromatism, courtship behavior, superfetation, and sexual selection index are all correlated with the matrotrophy index. Figure 2 shows that this concurs with the results of a  factor PFA. This small model fit also highlights a weakness of traditional factor analysis assumptions that fix the diagonal elements of the loadings matrix to be positive. In particular, dichromatism is unrelated to the other traits in the second factor, while the positivity constraint would have forced its inclusion. However, the most probable number of independent evolutionary processes is

factor PFA. This small model fit also highlights a weakness of traditional factor analysis assumptions that fix the diagonal elements of the loadings matrix to be positive. In particular, dichromatism is unrelated to the other traits in the second factor, while the positivity constraint would have forced its inclusion. However, the most probable number of independent evolutionary processes is  or

or  , with a log Bayes factor in favor

, with a log Bayes factor in favor  over

over  of

of  and a log Bayes factor in favor of

and a log Bayes factor in favor of  over

over  of

of  (Table 1). Since a log Bayes factor of only

(Table 1). Since a log Bayes factor of only  separates the

separates the  and

and  models, we include both models in our results, and the data strongly support these PFA models over the LMBD model (log Bayes factor

models, we include both models in our results, and the data strongly support these PFA models over the LMBD model (log Bayes factor  92).

92).

Figure 2.

Processes driving transitions to placental reproduction inferred through PFAs. Loading  estimates from the a)

estimates from the a)  , b)

, b)  and c)

and c)  factor models. Loadings size, coloring and density follow those of Figure 1. Note that the magnitude for dichromatism, courtship behavior, ornamental display traits, sexual selection index, and superfetation is less relevant since those data are discrete. We include the two factor model for direct comparison to the results of Pollux et al. (2014). Loadings in the more probable

factor models. Loadings size, coloring and density follow those of Figure 1. Note that the magnitude for dichromatism, courtship behavior, ornamental display traits, sexual selection index, and superfetation is less relevant since those data are discrete. We include the two factor model for direct comparison to the results of Pollux et al. (2014). Loadings in the more probable  and

and  factor models do not support an association between matrotrophy index and gonopodium length nor body weights and lengths.

factor models do not support an association between matrotrophy index and gonopodium length nor body weights and lengths.

Loadings for the independent evolutionary process factors  and

and  under the

under the  and

and  PFA models, respectively, recapitulate a negative association between the matrotrophy index and dichromatism, courtship behavior, and sexual selection index, and a positive association with superfetation (Fig. 2, first loading). Uncertainty measures

PFA models, respectively, recapitulate a negative association between the matrotrophy index and dichromatism, courtship behavior, and sexual selection index, and a positive association with superfetation (Fig. 2, first loading). Uncertainty measures  are

are  for all of these trait-factor relationships. However, unlike in Pollux et al. (2014), the PFA does not recover with high posterior probability a relationship between matrotrophy index and gonopodium length nor with body weights and lengths, suggesting that these were false positive findings. For both PFA models, second independent processes

for all of these trait-factor relationships. However, unlike in Pollux et al. (2014), the PFA does not recover with high posterior probability a relationship between matrotrophy index and gonopodium length nor with body weights and lengths, suggesting that these were false positive findings. For both PFA models, second independent processes  and

and  drive dichromatism, courtship behavior, ornamental display traits and sexual selection index positively and superfetation and gonopodium length negatively, where

drive dichromatism, courtship behavior, ornamental display traits and sexual selection index positively and superfetation and gonopodium length negatively, where  for each of these relationships except involving superfetation (

for each of these relationships except involving superfetation ( ) and for courtship behavior in

) and for courtship behavior in  (

( ). Both models also identify similar third independent processes

). Both models also identify similar third independent processes  and

and  relating body lengths and weights. We do however find more posterior certainty in the

relating body lengths and weights. We do however find more posterior certainty in the  relationships (all

relationships (all  ) than in the

) than in the  relationships (all

relationships (all  ). It is perhaps surprising that these size measurements are unrelated to any of the other reproductive characteristics. The only marked difference between the

). It is perhaps surprising that these size measurements are unrelated to any of the other reproductive characteristics. The only marked difference between the  and

and  factor models exists in the presence of a fourth evolutionary process

factor models exists in the presence of a fourth evolutionary process  in the

in the  factor model that controls the presence or absence of superfetation independently of all other traits.

factor model that controls the presence or absence of superfetation independently of all other traits.

The precision elements  for both the

for both the  and

and  factor models are all significantly greater than 1 and therefore indicate that, for both models, our PFA provides good insight into the relationship of the continuous traits (Table 2). Further, the precision elements are in broad agreement between the

factor models are all significantly greater than 1 and therefore indicate that, for both models, our PFA provides good insight into the relationship of the continuous traits (Table 2). Further, the precision elements are in broad agreement between the  and

and  factor models, as we expect due to the negligible difference in marginal likelihoods.

factor models, as we expect due to the negligible difference in marginal likelihoods.

Frequentist-based factor analysis is only identifiable if the number of parameters inferred for a variance/covariance matrix is greater than the number of parameters that need to be inferred for the factor analysis. Interestingly, our PFA model produces interpretable results in spite of the fact that the correlation model has 66 free parameters as opposed to 333 free parameters for the  factor model, and 436 free parameters for the

factor model, and 436 free parameters for the  factor model.

factor model.

Triggerfish Fin Shape

The fish family Ballistidae, commonly know as triggerfish, live mostly in reefs; however, the particular part of the reef in which they live can vary. This variability affects not only their diet, but also their mobility needs that fin shapes well reflect (Dornburg et al. 2011). To model shape changes through evolution, phylogenetic morphometrics often relies heavily on PCA (Revell 2009; Polly et al. 2013). However, deterministic data reduction via PCA can introduce bias (Uyeda et al. 2015) and, more importantly, inference of principal components while simultaneously adjusting for an uncertain evolutionary history remains a continuing challenge. PFA offers an alternative approach.

For  triggerfish species, Dornburg et al. (2011) sequence and align 12S (833 nucleotides, nt) and 16S (563 nt) mitochondrial genes and RAG1 (1471 nt), rhodopsin (564 nt) and Tmo4C4 (575 nt) nuclear genes, and Dornburg et al. (2008) digitally photograph and mark 13 semilandmark Cartesian coordinates for pectoral, dorsal, and anal fins, generating

triggerfish species, Dornburg et al. (2011) sequence and align 12S (833 nucleotides, nt) and 16S (563 nt) mitochondrial genes and RAG1 (1471 nt), rhodopsin (564 nt) and Tmo4C4 (575 nt) nuclear genes, and Dornburg et al. (2008) digitally photograph and mark 13 semilandmark Cartesian coordinates for pectoral, dorsal, and anal fins, generating  measurements per species. Among these morphometric measurements, the species Balistapus undulatus is missing dorsal and anal fins landmarks, and the species Rhinecanthus assasi lacks pectoral fin landmarks. For these, we assume the missing data are missing at random.

measurements per species. Among these morphometric measurements, the species Balistapus undulatus is missing dorsal and anal fins landmarks, and the species Rhinecanthus assasi lacks pectoral fin landmarks. For these, we assume the missing data are missing at random.

To accommodate phylogenetic uncertainty within  , we concatenate gene alignments into

, we concatenate gene alignments into  and model nucleotide sequence substitution along the unknown evolutionary history

and model nucleotide sequence substitution along the unknown evolutionary history  through the Hasegawa et al. (1985) continuous-time Markov chain with unknown transition:transversion rate ratio

through the Hasegawa et al. (1985) continuous-time Markov chain with unknown transition:transversion rate ratio  and stationary distribution

and stationary distribution  . We incorporate across-site rate variation using a discretized, one-parameter Gamma distribution (Yang 1994) with unknown shape

. We incorporate across-site rate variation using a discretized, one-parameter Gamma distribution (Yang 1994) with unknown shape  and proportion

and proportion  of invariant sites. To specify prior

of invariant sites. To specify prior  , we make relatively uninformative choices, documented in the BEAST extensible markup language (XML) file in the Supplementary material available on Dryad at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6320t.

, we make relatively uninformative choices, documented in the BEAST extensible markup language (XML) file in the Supplementary material available on Dryad at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6320t.

These triggerfish sequences and traits favor the  factor model with a log Bayes factor of

factor model with a log Bayes factor of  over the

over the  factor model and

factor model and  over the

over the  factor model (Table 1). Further, these data favor the

factor model (Table 1). Further, these data favor the  factor model over the multivariate Brownian diffusion (MBD) model with a log Bayes factor of

factor model over the multivariate Brownian diffusion (MBD) model with a log Bayes factor of  . Even if this support were equivocal, we caution against using a MBD to model these traits. The unknown variance matrix

. Even if this support were equivocal, we caution against using a MBD to model these traits. The unknown variance matrix  carries

carries  degrees-of-freedom that dwarfs the

degrees-of-freedom that dwarfs the  possible measurements.

possible measurements.

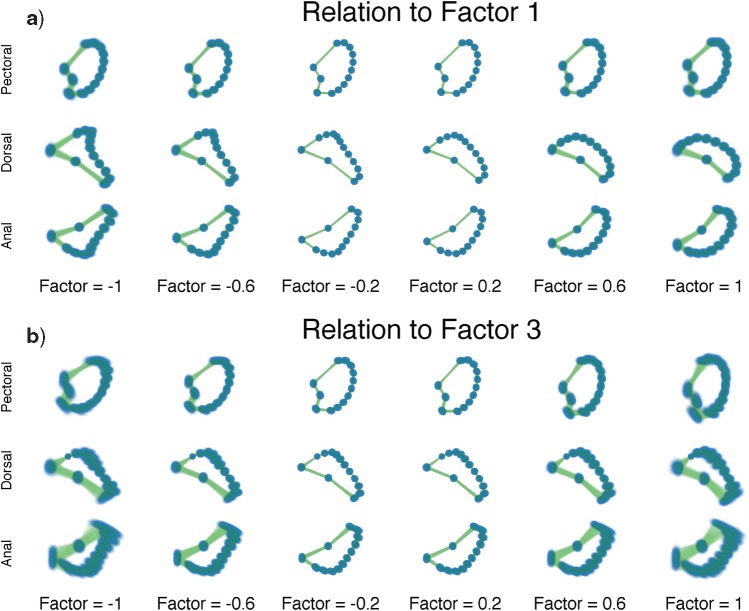

For two of the five factors in the  model, Figure 3 demonstrates how fin shape changes as a function of latent factor values. We vary

model, Figure 3 demonstrates how fin shape changes as a function of latent factor values. We vary  and

and  between

between  and

and  that approximates their highest posterior density range over their reconstructed evolutionary history. For

that approximates their highest posterior density range over their reconstructed evolutionary history. For  , increasing values lead to dorsal and anal fins that become less pointed and more rounded. For

, increasing values lead to dorsal and anal fins that become less pointed and more rounded. For  , increasing values lead to a counterclockwise rotation of the dorsal fin. Our credible band decreases in size as the factor value gets closer to 0 since the standard deviation of the posterior inference on our loadings is multiplied by these factor values as well.

, increasing values lead to a counterclockwise rotation of the dorsal fin. Our credible band decreases in size as the factor value gets closer to 0 since the standard deviation of the posterior inference on our loadings is multiplied by these factor values as well.

Figure 3.

Expected triggerfish fin shape given a range of a) first factor values  and b) third factor values

and b) third factor values  , holding all others constant. Purple dots estimate semilandmark locations. Green lines are interpolated to present a clearer outline of the fin shape. For the relation represented by

, holding all others constant. Purple dots estimate semilandmark locations. Green lines are interpolated to present a clearer outline of the fin shape. For the relation represented by  the dorsal and anal fins go from more pointed to less pointed. For the relation represented by

the dorsal and anal fins go from more pointed to less pointed. For the relation represented by  we see a rotation in the pectoral fin.

we see a rotation in the pectoral fin.

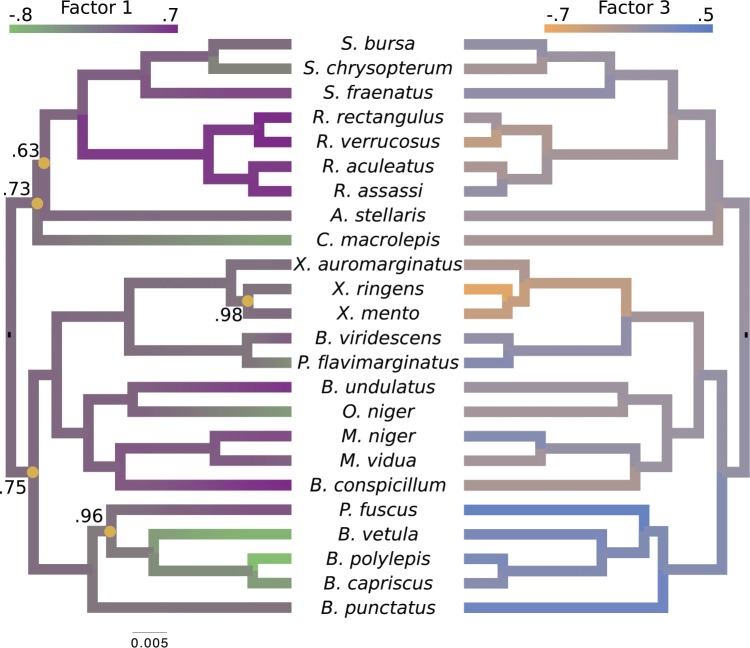

We also include the corresponding maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree, colored by factor value, with purple representing positive values and green representing negative values for the first factor  and the blue representing positive factor values and orange representing negative factor values for

and the blue representing positive factor values and orange representing negative factor values for  in Figure 4. This tree shows us that the species Balistes polylepsis and B. vetula, have negative factor values for

in Figure 4. This tree shows us that the species Balistes polylepsis and B. vetula, have negative factor values for  , but those species as well as the rest of the clade with the genus Balistes and species Pseudobalistes fuscus have positive factor values for

, but those species as well as the rest of the clade with the genus Balistes and species Pseudobalistes fuscus have positive factor values for  whereas the clade containing the genus Rhinecanthus has negative factor values for

whereas the clade containing the genus Rhinecanthus has negative factor values for  but a close to 0 factor value for

but a close to 0 factor value for  . Conversely, the genus Xanthichthys has a negative factor value for

. Conversely, the genus Xanthichthys has a negative factor value for  and a closer to 0 factor value for

and a closer to 0 factor value for  We also display posterior clade probabilities for those clades with probability

We also display posterior clade probabilities for those clades with probability  99%.

99%.

Figure 4.

Evolution of independent factors  driving triggerfish fin morphology along inferred phylogeny. The colorings display contemporary and ancestral first

driving triggerfish fin morphology along inferred phylogeny. The colorings display contemporary and ancestral first  and third

and third  factor values under a

factor values under a  factor PFA model. For

factor PFA model. For  , green represents positive values and purple represents negative values. For

, green represents positive values and purple represents negative values. For  , the scale is orange to blue. The Supplementary material available on Dryad contains plots for

, the scale is orange to blue. The Supplementary material available on Dryad contains plots for  ,

,  and

and  . Balistes polylepis and Balistes vetula have negative factor values for the first factor

. Balistes polylepis and Balistes vetula have negative factor values for the first factor  whereas the clade containing genus Rhinecanthus has positive factor values. In the third factor

whereas the clade containing genus Rhinecanthus has positive factor values. In the third factor  , the Balistes genus and the species Pseudobalistes fuscus have positive factor values whereas the genus Rhinecanthus has near 0 factor values. Conversely, the genus Xanthichthys has a negative factor value for

, the Balistes genus and the species Pseudobalistes fuscus have positive factor values whereas the genus Rhinecanthus has near 0 factor values. Conversely, the genus Xanthichthys has a negative factor value for  , and has a near 0 value for

, and has a near 0 value for  . We display the posterior clade probabilities for probabilities

. We display the posterior clade probabilities for probabilities  99%.

99%.

For brevity, we have only considered two factors in this section. We selected  and

and  since these factors relate distinctive information, however we include the results for the remaining factors in the Supplementary material available on Dryad. We additionally include our inference on the precision elements as well as our results on the inference on the other aspects of our tree model in the Supplementary material available on Dryad.

since these factors relate distinctive information, however we include the results for the remaining factors in the Supplementary material available on Dryad. We additionally include our inference on the precision elements as well as our results on the inference on the other aspects of our tree model in the Supplementary material available on Dryad.

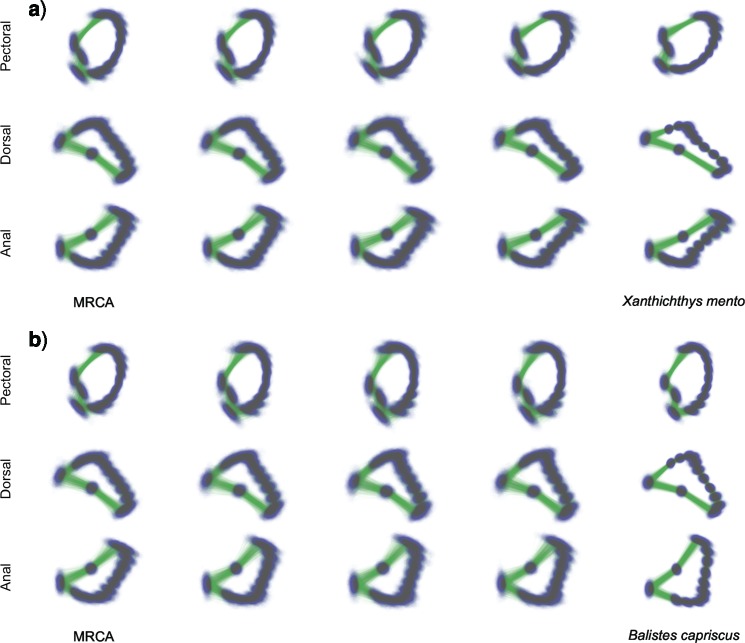

Lastly, PFA facilitates ancestral shape reconstruction. Figure 5 depicts inferred pectoral, dorsal and anal fin shapes for ancestors of Xanthichthys mento and Balistes capriscus at arbitrary points into their evolutionary past. We choose reconstructions at the MRCA of all 24 species in our study and  ,

,  and